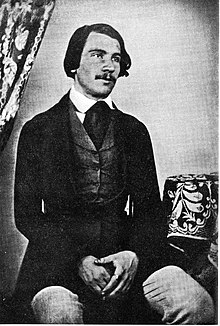

Jacob Burckhardt

Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (born May 25, 1818 in Basel ; † August 8, 1897 there ) was a Swiss cultural historian specializing in art history . He taught at the University of Basel for decades . He was well known for his book The Culture of the Renaissance in Italy .

Life

Jacob Burckhardt was born in Basel in 1818 as the fourth of seven children. He came from an old and successful family of the Basel Daig . His mother was Susanna Maria Burckhardt-Schorndorff (1782-1830). Several ancestors were clergy, including his father Jakob Burckhardt the Elder (1785–1858) was pastor of the Reformed Church in Basel. Since he was head of the Münster community, he was also Antistes and thus head of the Basel clergy. Burckhardt received a comprehensive humanistic education at home and at high school. His teachers gave him excellent knowledge of French, Italian and the ancient languages and encouraged his historical and literary inclinations. In order to deepen his language skills in French even further, he lived from 1836 to 1837 with the Godet family in Neuchâtel. In 1835 Burckhardt met Heinrich Schreiber and their friendship lasted until Schreiber's death.

In his hometown Jacob Burckhardt studied since 1837 at the request of his father Protestant theology . At the same time, he was already involved in history and philology . After four terms he moved to the University in Berlin to himself to the study of history, art history turn and philology. During this time he became a member of the Swiss Zofinger Association .

In Berlin from 1839 to 1843 he attended lectures by Leopold von Ranke , Johann Gustav Droysen , August Boeckh , Franz Kugler and Jacob Grimm, among others . It was here that Jacob Burckhardt made the acquaintance of Bettina von Arnim . In the summer of 1841 he spent a semester at the University of Bonn , where he joined the Maikäferbund , a late romantic poets' association around Gottfried Kinkel .

Because of Ranke's two works on Karl Martell and Konrad von Hochstaden , Jacob Burckhardt received his doctorate in Basel in 1843 in absentia . In the following year he completed his habilitation there in history and became an associate professor in 1845.

After completing his doctorate, he stayed in Paris for a few weeks, mainly dealing with French and Spanish art. Here he worked intensively in archives and libraries. In the years after 1844, Jacob Burckhardt worked temporarily as a political editor for the conservative Basler Nachrichten . In 1845 he interrupted this activity for the first time and later gave it up completely because his articles on the tense domestic political situation in Switzerland were controversial. Between 1846 and 1848 he stayed in Italy twice for a few months and in the meantime lived in Berlin , where he participated in the drafting of Brockhausschen Konversationslexikons . In 1848 he completed the lecture series "The Roman Empire" and a year later the lecture series "The golden age of the Middle Ages". As a result of a trip and study on site in Italy in 1853, the poetry collection appears in dialect E Hämpfeli Lieder .

From 1855 to 1858 Jacob Burckhardt was a full professor of art history at the Eidgenössisches Polytechnikum in Zurich . In 1858 he took over the chair for history and art history at the University of Basel , which he held until 1893. From then on he concentrated on his lectures, which initially covered all epochs of European cultural history and since 1886 had exclusively focused on art history. In addition, he emerged as a skilled speaker through public lectures.

Even Friedrich Nietzsche , who came to Basel from Leipzig as Germany's youngest university professor and was already considered a philological capacity at the age of twenty-four, praised Burckhardt as "our great, greatest teacher." Nietzsche often tried to get into conversation with his older colleague and probably also attended one of his lectures. Burckhardt, conversely, saw the talent of the young Nietzsche, but kept him politely at a distance and probably could not do much with his later philosophical works.

In 1872 Burckhardt turned down the offer to succeed Rankes at the University of Berlin. The last thirty years of his life he devoted himself entirely to teaching in Basel and did not publish any other works during this time. The art historian Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945) was one of his students . In 1886 Burckhardt gave up his professorship, but held the art history lectures for another seven years. The term "terrible simplificateur" much used in the German-speaking world (worse simplifier, Flat thinkers) was coined by him, he first appears in a letter Burckhardt to Friedrich von Preen of 24 July 1889. Burckhardt also professed the virtue of "dilettantism", to which he recognized the ability to provide an anti-specialist overview.

Burckhardt had already written down in 1891 that he wanted to be buried where he died. The grave should be a smooth stone, with the name and the date of birth and death. So he found his (temporarily) final resting place on the Wolfgottesacker . In 1931 the government council of Basel-Stadt decided to permanently close various cemeteries in Basel for 1951 and to provide Burckhardt with a dignified grave site in the Hörnli cemetery .

A simple plaque with his portrait was posthumously dedicated to Burckhardt for his achievements, which was made in 1898 by the medalist Hans Frei .

As early as 1930, on the initiative of Bertha Stromboli-Rohr (1848–1940), Burckhartd's great-nephew and painter Hans Lendorff (1863–1946), J. Alphons Koechlin (1885–1965), President of the Church Council of Basel-Stadt, proposed that Burckhardt, how even his father was to be buried in the cloister of Basel Minster . Out of piety and out of consideration for Burckhardt's last wish, this project was not carried out. Finally, Burckhardt was exhumed on October 14, 1936 and the wooden coffin was transferred to the Hörnli cemetery. Burckhardt's great-nephew, August Simonius -Bourcart (1885–1957) and his family later found their final resting place in the abandoned grave. Burckhardt's grave in the Hörnli cemetery was designed by the Basel architect Otto Burckhardt (1872–1952). Another great-nephew of Burckhardt was Felix Staehelin .

plant

Burckhardt's stays in Italy and the collaboration on Franz Kugler's handbooks on art history resulted in a reorientation towards the classic ideals of the Winckelmann , Goethe and Wilhelm von Humboldt epochs . Burckhardt took on more and more of a European-humanistic perspective and moved away from the prevailing paradigm of political history (cf. Raupp, column 855). This can be heard above all in his three "classical" works, which made him an outstanding cultural historian and co-founder of modern art history. Burckhardt resolutely contradicted historical-philosophical speculations, which viewed history as the temporal development of a superordinate, eternal historical process. For him the only constant phenomenon in history was human nature. The goal of existence and the whole of history remained a mystery to Jacob Burckhardt.

Burckhardt's first major work, published in 1853, is The Time of Constantine the Great, which he understood as a necessary transition from antiquity to Christianity and as the basis of medieval culture (cf. late antiquity ). In contrast to the prevailing view of the time, Burckhardt saw Emperor Constantine in a rather negative light, as a pure power politician whose turn to Christianity was only due to political considerations. In 1855 his second work Cicerone appeared, in which he describes the Italian art world from antiquity to the present.

His work Die Cultur der Renaissance in Italien (The Culture of the Renaissance in Italy), published in 1860, was of the greatest historiographical importance . During his travels in Italy, Jacob Burckhardt was strongly drawn to the Italian culture of the Renaissance .

For a long time this term was used as an epoch designation in art history. The first to use it directly for a historical epoch was Jules Michelet . It was only through Burckhardt's studies of Italian culture in the 15th and 16th centuries and the publication of his results that the "renaissance" was noticed in public opinion. The work is still considered the standard work on this era. In it Burckhardt paints an overall picture of Italian Renaissance society; This first comprehensive presentation of that epoch had a strong impact on the image of the Renaissance in Europe and became an exemplary work of cultural historiography. Georg Voigt, on the other hand, examined the movement of Italian humanism as a phenomenon of intellectual high culture. Both have in common the recognition that the Renaissance introduced modernity in Europe; they are both considered the founders of modern Renaissance research.

After his death, Burckhardt left four unpublished works ready for printing, including memories from Rubens . Greek cultural history and the widely read world historical considerations were also published from the estate . Burckhardt never intended to publish his course "On the Study of History", which he held three times from 1868 to 1872. While he was still on his deathbed, he gave his nephew Jacob Oeri (1844–1908) the task of having all the handwritten remains crushed, but Oeri was able to get him to inspect it. It was certainly not Burckhardt's intention that this insight should take several years and end with a publication. As is not uncommon in multiple lectures, the scripts are available in several versions, interspersed with inserts and updates. The handwritten material preserved - not counting the transcripts of students - is about twice as extensive as the text that Oeri then published for the book edition of 1905. Oeri's boldest innovation was probably the change in the title to World History Considerations , which Burckhardt's introductory lecture was supposed to bring closer to Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations .

Burckhardt's works were frequently published and translated. More than 1,700 letters from Burckhardt's lively correspondence have been preserved and have also been published. In autumn 2000, the publication of a new critical complete edition began in the publishing house CH Beck , a 27-volume company. Volumes 1 to 9 are dedicated to the writings published by Jacob Burckhardt himself or those prepared for publication, volumes 10 to 26 contain the works, lectures and lectures from the estate, volume 27 contains the index.

reception

A street is named after Jacob Burckhardt in Basel, Zurich and on the German side in Konstanz and Freiburg im Breisgau. The Jacob Burckhardt Prize of the Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Foundation in Basel is named after him, which is awarded for exemplary artistic achievements, as well as the prize of the same name, which is awarded by the Art History Institute in Florence - Max Planck Institute to young scientists of the Art history is awarded.

The highest banknote in Switzerland, the 1000-franc note , has been bearing the portrait of the Basel cultural historian since 1995.

The Swiss historian Aram Mattioli criticized Jacob Burckhardt's anti-Semitism and ethnocentrism in an essay . Burckhardt believed in the superiority of the «Caucasian racial peoples». Mattioli also criticized Burckhardt's rejection of democracy.

Fonts

- Carl Martell (1840)

- Artworks from Belgian cities (1842)

- Conrad von Hochstaden (1843)

- The time of Constantine the Great (late 1852, officially 1853)

- Cicerone (1855; digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- The culture of the Renaissance in Italy (1860; digitized version and full text in the German text archive )

- History of the Renaissance in Italy (1878)

Published from the estate:

- Memories from Rubens (1898)

- Greek cultural history (1898–1902)

- World historical considerations (1905)

- Historical fragments (collected from the estate of Emil Dürr , 1942)

Work editions:

- Jacob Burckhardt Complete Edition. Schwabe, Basel 1929–1934.

- Letters. Completely and critically edited edition using the handwritten estate made by Max Burckhardt . Eleven volumes. Schwabe, Basel 1949–1994.

- Collected Works. Ten volumes. Schwabe, Basel 1955–1959.

- Works. Critical complete edition. Edited by the Jacob Burckhardt Foundation, Basel. 29 volumes. Schwabe, Basel, and CH Beck, Munich, from 2002 (16 volumes published so far; edition plan ).

literature

- Stefan Bauer: Polis image and understanding of democracy in Jacob Burckhardt's "Greek Cultural History" ( contributions to Jacob Burckhardt , Volume 3), Schwabe, Basel and CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-7965-1674-0 .

- Laura Bazzicalupo: Il potere e la cultura. Sulle riflessioni storico-politiche di Jacob Burckhardt . ( Le Parole e le idee , Volume 1). Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Napoli 1990, ISBN 88-7104-240-9 .

- Leonhard Burckhardt , Hans-Joachim Gehrke (Hrsg.): Jacob Burckhardt and the Greeks. Lectures at an international specialist conference in Freiburg i. Br. Schwabe, Basel and CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-7965-2211-4 .

- Max Burckhardt: Jacob Burkardt in the last years of his life. In: Basler Journal of History and Archeology , vol 86, 1986, page 113. - 134.

- Andreas Cesana , Lionel Gossman (ed.): Encounters with Jacob Burckhardt: Lectures in Basel and Princeton on the hundredth anniversary of death / Encounters with Jacob Burckhardt: centenary papers ( contributions to Jacob Burckhardt , Volume 4). Basel 2004.

- Emil Dürr : Freedom and Power with Jacob Burckhardt. Helbing and Lichtenhahn, Basel 1918.

- Emil Dürr: Jacob Burckhardt as a political publicist. With his newspaper reports from 1844/45. Fretz and Wasmuth, Zurich 1937.

- Luca Farulli: Burckhardt e Nietzsche. Polistampa, Firenze 1998.

- Hermann Fricke : Wanderer to wisdom and freedom. Calvinist traits in Jacob Burckhardt's and Theodor Fontane's idea of the state. In: Yearbook for Brandenburg State History , ed. from the Landesgeschichtliche Vereinigung für die Mark Brandenburg , Vol. 11 (1960), pp. 5-13, ISSN 0447-2683 ( digitized version ).

- Peter Ganz : Burckhardt, Jacob. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Maurizio Ghelardi: Relire Burckhardt. Textes inédits en français de Jacob Burckhardt. Cycle de conférences . École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-84056-049-6 .

- Hans Rudolf Guggisberg (Ed.): Dealing with Jacob Burckhardt. Twelve Studies ( Contributions to Jacob Burckhardt , Volume 1). Schwabe, Basel, and Beck, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-7965-0972-X .

- Hans Rudolf Guggisberg: The American post-fame Jakob Burckhardts. In: Swiss Monthly Issues: Journal for Politics, Economy, Culture , Vol. 44, 1965, pp. 747–754.

- Horst Günther : “The spirit is a burrower”. About Jacob Burckhardt . Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-596-13670-9 .

- Wolfgang Hardtwig : Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897). In: Lutz Raphael (Hrsg.): Classics of the science of history . Vol. 1: From Edward Gibbon to Marc Bloch . Beck, Munich 2006, pp. 106-122.

- Karl Heinrich Höfele: About Jakob Burckhardt's travels. In: Swiss Monthly Issues: Journal for Politics, Economy, Culture , Vol. 44, 1965, pp. 754–760.

- Karl Emil Hoffmann: Jakob Burckhardt's poems. In: Schweizer Illustrierte , Vol. 23, 1919, pp. 253–265.

- Werner Kaegi : Jacob Burckhardt. A biography . Seven parts in eight volumes. Schwabe, Basel 1947–1982.

- Werner Kaegi : The idea of transience in Jacob Burckhardt's youth history. In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Vol. 42, 1943, pp. 209–243.

- Werner Kaegi: Burckhardt, Jacob Christoph. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1957, ISBN 3-428-00184-2 , pp. 36-38 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Löwith : Jacob Burckhardt ( Complete Writings , Volume 7). Metzler, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-476-00513-5 .

- Alfred von Martin : Nietzsche and Burckhardt . Reinhardt, Munich 1941 (4th edition, Erasmus-Verlag, Munich 1947).

- Aram Mattioli : Jacob Burckhardt's anti-Semitism. A new interpretation from the point of view of the history of mentality. In: Swiss History Journal . Volume 49, 1999 ( full text ).

- Aram Mattioli: Jacob Burckhardt and the limits of humanity . Provincial Library, Weitra 2001, ISBN 3-901862-11-0 .

- Kurt Meyer: Jacob Burckhardt. A portrait . Wilhelm Fink, Munich. ISBN 978-3-7705-4796-8 .

- Gustav Münzel: The correspondence between Jakob Burckhardt and Heinrich Schreiber. In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Vol. 22, 1924, pp. 1–85. ( Digitized version ).

- Heinrich Oeri, Max Burckhardt : Letters from Jacob Burckhardt's youth. In: Basler Journal of History and Archeology , vol 82, 1982, p.97. - 147. ( digitized ).

- Werner Raupp : Jacob (Christoph) Burckhardt. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 14, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-073-5 , Sp. 844-861. (with detailed bibliography).

- Walther Rehm : Jacob Burckhardt . Huber, Frauenfeld and Leipzig 1930.

- Walter Rehm: Jakob Burckhardt and Franz Kugler. In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde , Vol. 41, 1942, pp. 155–252.

- Paul Roth : Documents on Jakob Burckhardt's career. In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde , Vol. 34, 1935, pp. 5–105.

- Jörn Rüsen : Jacob Burckhardt . In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German historians . Volume 3, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, pp. 241-262.

- René Teuteberg : Who was Jacob Burckhardt? Vetter, Basel 1997, ISBN 3-9521248-0-X .

- Mario Todte: Georg Voigt (1827-1891). Pioneer of historical research on humanism. Leipziger Universitäts-Verlag, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-937209-22-0 .

- Rudolf Wackernagel : Letters from Jacob Burckhardt to Bernhard Kugler 1867–1875 . In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Vol. 14, 1915, pp. 351–377. ( Digitized version ).

- Wilhelm Waetzoldt : Jacob Burckhardt as an art historian. EA Seemann, Leipzig 1940.

- Ernst Ziegler : Jacob Burckhardt on Lake Constance. The Basel historian and university professor, his lecture manuscripts and the transcripts of his audience. In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings, Volume 123 (2005), pp. 113–127 ( digitized version ).

- Ernst Ziegler: Jacob Burckhardt - once different. In: Basler Stadtbuch, 1972, pp. 167–191.

Web links

- Publications by and about Jacob Burckhardt in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Literature by and about Jacob Burckhardt in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Jacob Burckhardt in the German Digital Library

- Works by Jacob Burckhardt in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Works by Jacob Burckhardt at Zeno.org .

- Burckhardt at 200: The Civilization of the Renaissance reconsidered , British Academy, London 31 May - 1 June 2018

- Jacob Burckhardt at arthistoricum.net - the historical context and digitized works in the “History of Art History” portal

- Jacob Burckhardt's estate in the Basel University Library

- Burckhardt Association 1818-2018 The association was founded with the aim of remembering J.Burckhardt on the occasion of his 200th birthday with various cultural and scientific events.

- Jacob Burckhardt In altbasel

- Family tree at stroux.org

Remarks

- ^ Werner Kaegi : Jacob Burckhardt. A biography. Volume 1: Childhood and Early Adolescence. Schwabe Verlag, Basel 1947, p. 577.

- ↑ See the new edition with the author's name E Hämpfeli Lieder. In: Basler Stadtbuch . 1910, pp. 137-156 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Cf. Burckhardt: Weltgeschichtliche Considerungen, p. 36.

- ↑ Stefan Krmnicek, Marius Gaidys: Taught images. Classical scholars on 19th century medals. Accompanying volume to the online exhibition in the Digital Coin Cabinet of the Institute for Classical Archeology at the University of Tübingen (= From Croesus to King Wilhelm. New Series, Volume 3). University Library Tübingen, Tübingen 2020, p. 30 f. ( online ).

- ^ Marc Sieber : Jacob Burckhardt's disturbed grave rest. Retrieved October 26, 2019 .

- ↑ old Basel: The Jacob Burckhardt case. Retrieved May 7, 2019 .

- ↑ On Burckhardt's theory of history, see the article by Jörn Rüsen: The clock that strikes the hour. History as a process of culture with Jacob Burckhardt. In: Karl-Georg Faber, Christian Meier (eds.): Historical processes ( contributions to history, volume 2). Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1978, pp. 186–217.

- ↑ Andreas Cesana: History as Development? On the critique of historical-philosophical developmental thinking. De Gruyter, Berlin 1988, p. 261 ff. ( Google book ).

- ^ Jacob Oeri (ed.): Jakob Burckhardt: Weltgeschichtliche Considerungen. About studying history. Munich 1982, p. 169.

- ↑ Aram Mattioli: Jakob Burckhardt and the limits of humanity. Provincial Library, Weitra 2001, p. 14.

- ↑ Mattioli: Jakob Burckhardt and the Limits of Humanity, p. 17.

- ↑ Mattioli: Jakob Burckhardt and the Limits of Humanity, p. 48.

- ↑ Jacob Burckhardt: The time of Constantine the Great. Edited by Hartmut Leppin, Manuela Keßler and Mikkel Mangold. Munich 2013, here p. 574.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Burckhardt, Jacob |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Burckhardt, Jacob Christoph (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss cultural historian with a focus on art history |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 25, 1818 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Basel |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 8, 1897 |

| Place of death | Basel |