Elberfeld uprising

The Elberfeld uprising of May 1849 was part of the imperial constitution campaign and broke out against the background of the non-recognition of the Frankfurt imperial constitution by the Prussian government and the final rejection of the German imperial title by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV . A security committee exercised control over the city for several days before the uprising collapsed.

prehistory

The movement in Elberfeld was part of a whole series of unrest in Prussia . Other places in the Rhine Province and in the Province of Westphalia where similar events occurred were Solingen , Graefrath , Düsseldorf , Siegburg or Hagen . Also known are the Prüm armory storm and the Iserlohn uprising . This was preceded by the dissolution of the second chamber of the Prussian state parliament by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. After the parliament had recognized the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution. The monarch also finally rejected the acceptance of the imperial crown. In order to forestall possible unrest, the Prussian government declared a state of siege and mobilized the Landwehr .

Start of movement

This met with outrage in Elberfeld. There the “political club”, which belonged to the democratic Central March Association , played an important role. A popular assembly organized by the “political club” was followed on April 29, 1849 by over a thousand people who passed a protest resolution. The following day the resolution was passed to the regional council in Düsseldorf. On May 1, 1849, the local council discussed the situation. The lawyer Hermann Höchster was successful with his application to criticize the dissolution of the second chamber. A commitment to the imperial constitution was rejected with a narrow majority of 12 to 11 votes, but the fact that the municipal council discussed general political issues at all earned it the disapproval of the provisional district president Wilhelm von Spankeren.

On May 3rd, a newly established Landwehr committee called the members of the Landwehr from Elberfeld to a meeting. At least 153 Landwehr soldiers declared the government under Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg to be hostile to the people. “The undersigned Landwehrmen of Elberfeld recognize and declare that the ministry surrounding the crown is to be regarded as an anti-grassroots ministry and they consider themselves relieved of the absolute crown. On the other hand, they agree to the constitution laid down by the Frankfurt National Assembly and are determined to bring about the introduction of this constitution for Germany with their person and honor. ” Hugo Hillmann was one of the leading militants . The committee decided to meet permanently. After the first drafting orders were issued on May 5th, the Landwehr Committee called on the Landwehr members of the city and the neighboring communities to resist, with moderate success. The landwehr men from the area expressly distanced themselves from the anarchist endeavors, but most of the Elberfeld landwehr men also followed the call to Essen. Nevertheless, the provisional District Administrator Carl Friedrich Melbeck feared unrest and called in the military on May 7th. On the same day, the Landwehr men who rebelled in the Elberfeld region called on all members of the Landwehr in the former Grand Duchy of Berg and the County of Mark to take action against the government's illegal measures, if necessary by force of arms.

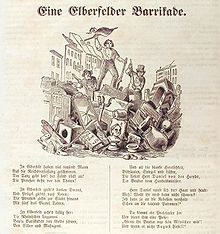

Barricades in Elberfeld

On May 9, 1849, against the will of Mayor Johann Adolf von Carnap , regular troops actually moved into Elberfeld. Only then did the building of barricades begin. The attempt by the military to overcome the barricades without force of arms and to arrest the members of the Landwehr Committee failed. The troops then withdrew and did not initially take action when an angry crowd damaged Mayor Carnap's house and freed numerous prisoners from prison. In the evening there were clashes in which several people died. The next day the troops withdrew, presumably to fight the unrest in Düsseldorf. The mayor and senior officials also left the city.

Establishment of the safety committee

In the power vacuum, the political club and the Landwehrmen's committee formed a "security committee" on May 10th. This took over the executive power in Elberfeld. The community council members who remained in the city transferred the authority of the community council, including the care of the city treasury, to the security committee. The committee tried to restore law and order. At the same time he began to prepare the defense of the city against the expected Prussian troops.

2000 to 3000 volunteers streamed to Elberfeld to support the uprising, especially from the surrounding towns and communities. Friedrich Engels joined them from Cologne . He hoped to be able to turn the land defense units into a revolutionary army and counted on the uprising to encompass the whole of the Rhineland from Elberfeld. Instead of the black, red and gold, he wanted to put the red flag. On Engel's advice, the former Prussian officer Otto von Mirbach was commissioned with the military management. Engels himself was given the management of the fortification work and command of the artillery.

An important factor was the attitude of the vigilante group founded in 1848. This had elected Ferdinand van Poppel as the new commander on May 12, 1849. The vigilantes opposed the disarmament ordered by Mirbach. However, she promised not to take action against the security committee.

Negotiating delegation

Under pressure from the politically moderate forces, a delegation made up of the doctor Alexander Pagenstecher , the manufacturer Friedrich Wilhelm Simons-Koehler and the district court president Johann Friedrich Hector Philippi was sent to Düsseldorf and later to Berlin for negotiations . Friedrich Wilhelm IV did not receive the group. Ministers from Elberfeld, August von der Heydt and Ludwig Simons , did not speak to the delegation in an official capacity, but only as private individuals. The Berlin delegation sent a telegram to the Security Committee on May 16. However, this was formulated in a misleading manner, so that one believed in Elberfeld that the king had approved the imperial constitution.

Collapse of movement

In Elberfeld itself a messenger had been sent to Frankfurt am Main to ensure the support of the National Assembly. Attempts were also made to contact the security committee in Iserlohn and that of other rebellious cities. Command companies tried to steal weapons in the surrounding area. At the same time, however, fear of social revolutionary unrest also increased; this led the security committee to ban Friedrich Engels from the city.

On the same day as the telegram from the Berlin delegation arrived, an ultimatum from the President of the Rhine Province expired.

The hope of success in Berlin on the one hand and the impending invasion of the Prussian troops on the other, caused the movement to collapse quickly. Most of the foreign volunteers left the city. The remaining units were outnumbered by the vigilante group. Von Mirbach agreed to withdraw, but made this dependent on the payment of a considerable sum of money. The banker Daniel von der Heydt , who was captured at the beginning of the uprising, was taken hostage. On May 17, 1849 von Mirbach and his remaining troops left the city to join the uprising in the Palatinate. Most of the irregulars were captured soon afterwards.

consequences

Immediately afterwards, the vigilante secured the strategic points of the city. After the resignation of the municipal council members belonging to the security committee, the latter was reconstituted and passed a submission resolution. Numerous leading supporters of the uprising then fled. On May 19, Prussian troops occupied the city. The mayor was on leave and the municipal council was dissolved. In 1850, 150 people involved were tried by a jury.

Today a wide strip of cobblestones and a name plaque on the wall opposite the Von der Heydt Museum , the former town hall, remind of the location of the main barricade and those who were killed there.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ cit. after Valentin, p. 471

literature

Contemporary literature

- Karl Chr. Beltz: Elberfeld in May 1849. The democratic movements in Bergisch and the county of Mark. In addition to an appendix. Bädeker, Elberfeld et al. 1849, digitized .

- Friedrich Engels : The German Reich constitution campaign. First in: Neue Rheinische Zeitung. Political-Economic Review, Issue 1–4. Hamburg, 1850 online version

- Carl Hecker : The uprising in Elberfeld. In May, 1849, and my relationship to it. Bädecker (di: Bädeker) in commission, Elberfeld 1849, digitized .

- Vinzenz Zuccalmaglio: The great battle at Remlingrade, or the victory of the Bergische farmers over the Elberfeld all-world barricade heroes on May 17, 1849. Bädeker, Koblenz 1849, digitized .

Scientific literature

- The Elberfeld uprising in May 1848 . Edited and introduced by Johann Friedrich Hector Philippi. Reprint from: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein . Vol. 50 [NF Vol. 40] 1917

- Veit Valentin : History of the German Revolution from 1848–1849. Volume 2: Until the end of the people's movement in 1849. Ullstein, Berlin 1931, p. 471f.

- Klaus Goebel , Manfred Wichelhaus (ed.): Uprising of the citizens' revolution in 1849 in the West German industrial center. Hammer, Wuppertal 1974, ISBN 3-87294-065-1 .

- Helmut Elsner, M. Knieriem, Brigitte Traude (eds.): Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Your position in the revolution of 1848/49 . H. Freistühler Verlag, Schwerte / Ruhr 1979.

- Uwe Eckardt: The Elberfeld Uprising in 1849 . In: Michael Knieriem Ed .: "Michels Erwachen". Emancipitation through insurrection? Studies and documents for the exhibition . Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 1998 ISBN 3-87707-526-6 , 31-37

- Uwe Eckardt: "... the future belongs to democracy!" Comments on the riots in Elberfeld. In: Wilfried Reininghaus (ed.): The revolution of 1848/49 in Westphalia and Lippe. Münster, 1999. 297-318

- Volkmar Wittmütz: "Assaults up to this point are very much feared". The Elberfeld uprising in May 1849 and its effects in Velbert. In: Romerike Berge . 49, 2 (1999), pp. 10-15