Duchy of Berg

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Duchy of Berg | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

| map | |

|

|

| Duchy of Berg in the 15th century | |

| Alternative names | Mountains |

| Arose from | Ruhrgau , Deutzgau and Auelgau of the Duchy of Lower Lorraine |

| Form of rule | monarchy |

| Ruler / government | Count / Duke |

| Today's region / s |

DE-NW

|

| Reichskreis | Lower Rhine-Westphalian |

| Capitals / residences |

Berge Castle in Altenberg , from 1133 Castle ad Wupper , from 14th century Düsseldorf |

| Dynasties | Berg , Limburg-Arlon , Jülich-Heimbach |

| Language / n |

German

|

| Incorporated into |

Grand Duchy of Berg

|

The Duchy of Berg ( Latin: Ducatus Montensis or Ducatus Bergensis ) was a territory on the right bank of the Rhine of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation . It belonged to the Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Circle and was landständisch written. It existed from the 11th century until 1380 as a county and then until 1806 as the Duchy of Berg, after which it existed for a few years in a greatly changed form as the Grand Duchy . For a long time Berg was united with the Duchy of Jülich and alternately with various other territories in personal union. The seat of power was initially Castle Berge in Altenberg , from 1133 then Castle Castle and from the late 14th century the Düsseldorf Castle .

geography

The Duchy of Berg comprised an area of 2,975 km² with 262,000 inhabitants around 1800 and was located on the right bank of the Rhine between the Reichsstift Essen , the Reichsabbey Werden , the County of Mark , the Reichsherrschaft Homburg , the County of Gimborn , the Duchy of Westphalia , the Electorate of Cologne , the Principality of Moers and the Duchy of Kleve .

Its border ran in the west along the Rhine , with the exception of the Kurkölnischen places Deutz , Poll , Vingst and Kalk , the areas around the Drachenfels castle and the Wolkenburg as well as two smaller parts to the right and left of the mouth of the Sieg near Beuel ( Vilich Abbey ). The duchy also included areas on the left bank of the Rhine, which were either located directly on the banks of the Rhine or were exclaves in the Electorate of Cologne. These were the freedom Wesseling , Rodenkirchen , Orr , Langel and Rheinkassel . In the north, the territory ended roughly at the level of the Ruhr with the exception of the Klevian city of Duisburg , whereby the river in the area of (Oberhausen-) Alstaden and Mülheim an der Ruhr was even exceeded, in the south the border line corresponds to the Rhine (south of Bad Honnef ) in an east-northeast direction (south of the Sieg ) of today's border between North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate. The eastern border resulted from the geographically relatively open transition to Grafschaft Mark , at the level of Waldbröl, for example on the Schwelm - Wipperfürth - Gummersbach line .

Today, the administrative districts of Düsseldorf and Cologne , as far as they lie to the right of the Rhine and south of the Ruhr, roughly cover the historical territory of the duchy.

The central mountain region Bergisches Land , consisting of the Niederbergisches and Oberbergi country , in which case the Wupper is used as a geographical border, owes its name to a nearly 1,000-year affiliation with the Duchy of Berg.

Today the term Bergisches Land is primarily used geographically for the higher (= "mountainous") regions of the former duchy, as it is often misunderstood as the "land of mountains". This term is hardly used anymore to describe the historical area, which started 900 years ago from Berge Castle on the Dhünn .

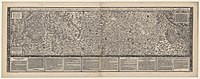

Old cards

Numerous old maps have survived for the area of the Duchy of Berg .

| year | author | Surname | Scan / Scan available at |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1558 | Caspar Vopelius (1511–1561) | Recens et Germana Bicornis ac vuidi Rheni omnium Germaniae Amnium celeberrimi descriptio, additis Fluminib [us]. Electorum Provinsiis, Ducat., Comita., Oppi. et Castris Praecipuis magna cum diligentia ac sumptib. collecta ("Rheinlaufkarte") |

|

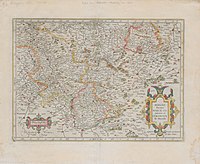

| 1594 | Gerhard Mercator (1512–1594) | Berghe Ducatus, Marck Comitatus et Coloniensis Dioecesis |

|

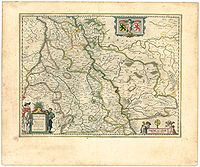

| 1610 | Hessel Geritz and Willem Ians (1571–1638) | de Hertochdommen Gulick, Cleve, Berghe en de Graeffschappen van der Marck en Ravensbergh |

|

| 1620 | Mercator (1512–1594) / Hondius (1563–1612) | Berghe Ducatus, Marck Comitatus et Coloniensis Dioecesis |

|

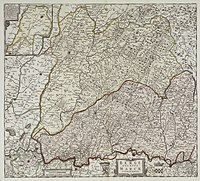

| 1660 | Willem Blaeu (1571-1638) | Ducatus Juliacensis, Cliviensis, Montensis et Comitatus Marciae et Rapensbergae |

|

| 1690 | Gerard Valck (1651–1726) / Pieter Schenk (1660–1711) | Mountains ducatus Marck comitatus |

|

| 1700 | Guillaume Sanson (1633-1703) | Le duché de Berg, le comté de Homberg, les seigneuries de Hardenberg et de Wildenborg |

|

| 1700 | Johann Baptist Homann (1664-1724) | Archiepiscopatus et electoratus Coloniensis ut et ducatuum Juliacensis et Montensis nec non comitatus Meursiae |

|

| 1715 | Erich Philipp Ploennies (1672–1751) | Topographia Ducatus Montani |

|

| 1730 | Matthäus Seutter (1678–1757) | Ducatus Iuliacensis, Cliviensis et Montensis, ut et Principatus Meursiani et Comitatus Zutphaniensis novissima et accuratissima Delineatio |

|

| 1750 | ? | Accurate LandCarte of the Hertduchesses Iulich, Clev and Bergen |

|

| 1750 | Homann heirs | Ducatus Juliaci & Bergensis |

|

| 1757 | Le Rouge | Duches de Bergue et Juliers, Electorat de Cologne Gueldre et comte de Meurs |

|

| 1790 | Carl Friedrich von Wiebeking (1762–1842) | Carte Of The Duchy Of Berg | digital.ub.uni-duesseldorf.de |

| 1797 | FL Güssefeld (1744–1808) | Chart of the course of the Rhine from Coblenz to Wesel, presenting the Duchy of Berg, the counties of Wied, Nieder-Isenburg and other countries |

|

| 1898 | Wilhelm Fabricius (1861–1920) | The Rhine Province in 1789 |

|

history

prehistory

When the Romans first appeared, the Rhine Valley was inhabited by Ubiern , and later by Tenken and Sugambrians , while the higher parts of the country were almost uninhabited. During the Roman times on the Rhine, the tribes settled in the Rhineland joined together to form the Ripuarian Franks . At that time the area was borderland to the Saxons . The previously heavily forested high areas of the country were only settled after the Saxon Wars of Charlemagne from the Rhine and the Ruhr. The Christianity found in the northern Bergisch Land first 700 input by Suitbert , a student of Bede , of the pen on an island in the Rhine in Dusseldorf Kaiserswerth founded. The further Christianization began in the southern part of the country from Cologne and Bonn monasteries and lasted in the mountainous region into the 10th century. According to the Franconian district division , the Bergisches Land in the old settlements on the Rhine and Ruhr consisted of the Ruhrgau , also called Duisburggau , Deutzgau and the Auelgau .

Creation of the county of Berg

If Emperor Otto the Great (936–973) had founded a firmly established empire with a tight imperial administration, in which the bishops were the high officials and dukes and counts were enfeoffed vassals, a change gradually took place under the Salian emperors (1024–1125) until the age of territorial principalities began under Henry IV (1056–1106), which led to the ousting of the counts . The remote position of the Bergisches Land, due to the mountainous terrain, which always favored the formation of smaller territories, left the initially small allod from the royal estate or imperial estate on the Dhünn , from the possessions between Rhine and Westphalia acquired through inheritance, from the bailiwicks of Essen, Werden, Gerresheim, through the possession of the Deutzer Vogtei, the forest sovereignty over the Königsforst , the Vogtei Siegburg with the Auelgau and the forest district Miselohe, the county of Berg emerged around the middle of the 11th century.

Under the anarchic conditions in the middle of the 11th century, when the property of aspiring aristocrats expanded beyond the old boundaries through inheritance, conquest, purchase and pledges, the boundaries of the old district division dissolved with the descent of the counts. The Count Palatine of the Ezzone now also tried to break away from royal service and develop their own power. This failed because of the resistance of the Cologne Erzstuhl. In 1060, Count Palatine Heinrich was defeated by the Archbishop of Cologne , Anno II, in a feud. This changed the ownership and pledge relationships in the area between Sülz and Wupper. Allodes and righteous people were lost to the Count Palatine on the right bank of the Rhine and on the northern Lower Rhine . Anno was able to assert his interests in the reallocation of the royal fiefs on the right bank of the Rhine with the help of his guardianship over the underage King Heinrich IV .

Especially in this area, through which the roads to Westphalia led to possessions of various Cologne churches, including the military routes between Cologne and Dortmund , which are important for land transport , Anno needed a loyal and reliable informant to succeed the Ezzone. According to documents, there was a noble family resident in this area, which had some allodial possessions between Erft and Rhine and held various rights there, but had no ancestral seat or castle. The royal fiefs to be newly awarded were not only opposite the archbishop's property, but also the mostly scattered property of the counts, who were still settled on the left bank of the Rhine. This family was related to respected count families on the left bank of the Rhine who were favored by the Cologne Erzstuhl. The father of Adolf I. von Berg , the first verifiable count from the Berg family, who came from this house , saw opportunities for ascent on the right bank of the Rhine. His first castle, Berge Castle near Altenberg, was located in the middle of his fiefdom there . The beginnings of the Counts of Berg lie in this fortification.

The first counts of Berg

As early as 1056, an Adolf was mentioned in a document as Vogt of the Gerresheim Abbey , at that time they owned the hereditary bailiwick over the Deutz Abbey (first verifiable from 1311) and the Werden Abbey .

The bailiffs had supervisory and protective duties for the large estates and possessions and the legal authority for the ecclesiastical manors, since ecclesiastical or ecclesiastical institutions did not have their own jurisdiction.

In a period of about five decades, the Lords of Berge (Altenberg) had acquired so much property and offices that they had become a powerful family in Deutzgau. The rise of the Lords of Berg, helped by the weakened power of the empire, went so quickly that at first only the Lord of Hückeswagen and the later appearing of the Lord von Hardenberg managed to keep their place of jurisdiction independently. The Counts of Berg were the only sovereign family between Sieg and Ruhr , between the Counts of Sayn and those of Kleve . They appeared in the vicinity of the emperors and Cologne archbishops for a long time before Count Adolf I was mentioned in a document as Count von Berg in 1101.

Until around 1400, old property rights are still documented for the berger in Gymnich , in Rommerskirchen tithe rights in the Erft area . There were old family ties to the Saffenburg family , the Counts of Nörvenich and probably also to the Counts of Hochstaden - Wickrath .

Tradition - the historical basis of the origin

The “official” counts of the Counts and Dukes of Berg often lead to confusion. On the one hand, the family tree of the Berger has been changed and supplemented again and again in the last decades, depending on the document situation, through additions or new interpretations, other local researchers doubt the results again. In addition, there is a wide variety of names, as the marriage of the nobles, which was customary at the time, with the planned enlargement of the areas and counties, allowed several counties to appear in the name of the counts. Depending on the type, place and jurisdiction of the count, often only the title required for the notarization appeared in earlier centuries. Even proven experts in the history of the Bergisches Land and those familiar with the surrounding historical territories have difficulty finding a consistent line.

The oldest reference to the family history of the Berger comes from a medieval oral chronicle transmitted by Levold von Northof (i.e. an orally transmitted family history). In his "Chronica comitum de Marka" (completed in 1358), according to the vast majority of historians, a relatively credible picture of the family history is drawn, since he spent his studies with the count's son Adolf VI. spent by mountain . The core of its tradition is the statement that the Märker and Berger had a common family history until the division of the country in 1160.

Family relationships, the favor of the Archdiocese of Cologne and marriage in the sense of state politics helped the first Bergisch counts to develop and expand their rule undisturbed, whereby the personal abilities of the counts also ensured high recognition and participation in decisions at "Hofe".

Until 1225, large parts of the later Bergisches Land were under the rule of the Berger. It was based on various foundations: the rule over land, feudal property, pledges, the clearing of the population, church bailiffs, the count's jurisdiction, city rule, forest justice and regalia .

The geopolitical situation of the Bergisches Land in the emerging age of the territorial principalities made it possible for the lords of Berg to develop into a family that was able to adapt to the fluctuating balance of power in the empire and thus through the brilliant political superiority of the counts was moved to expand his property in such a way that the Berg territory became more and more powerful until it came into the ranks of the greats.

The Counts of Berg

House Berg (1068-1225)

Adolf I. von Berg

From around 1080 a person called himself Adolf, the third Deutzer Vogt of this name, first with the addition of "vom Berge" (Latinized: "de Monte"). There are also earlier documents that list the cognomen “de Monte” and “de Berge”, but there are doubts as to their authenticity or authenticity. Otto Oppermann , for example, dates these documents to the second half of the 12th century. Around 1080 silver coins were minted in Adolf's name with the inscription "ADOLPHUS COMES DE MONTE", but it was not until 1101 that an Adolf von Berg had the title of count in a certificate from Emperor Heinrich IV . From this point on he was called Count Adolf I von Berg , with him the order of the counting began, since the predecessor with the name Adolf has not yet been identified as Count von Berg. Adolf I died in 1106. Through his wife Adelheid von Lauffen , whose father Heinrich came from Lobdengau on the lower Neckar and whose brother, Archbishop Bruno von Trier, was perhaps the godfather of Adolf's son Bruno, the later provost of Koblenz and as Bruno II. Archbishop of Cologne, Adolf I may have acquired further allodial property and thus considerably increased his rights , since Adelheid von Lauffen brought the inheritance of her mother Ida von Werl into the marriage with him. This property extended around the Wupperbogen, which the Wupper still forms today. This moved the ancestral seat of the Count near Altenberg , Berge Castle , into a marginal position. The Hövel Castle in Bockum-Hövel did not belong to the inherited property , as there was an Adolf von Hövel named for this in 1080 and 1121, who was identified by Paul Leidinger with an Adolf von Berg. Hövel can be proven to be Bergisch even before Adolf Werler's marriage to Adelheid.

Adolf II von Berg

Adolf I's successor was his son Adolf II von Berg . Born between 1095 and 1100, he ruled from 1115 to 1160. In 1120 at the latest, he married an Arnsberger woman from the Werl family with the name Adelheid; as a result, the Berger came to further Westphalian possessions, mainly between the Emscher and Ruhr, in the Bochum area and near Unna, Kamen and Hamm, Telgte and Warendorf; the extent of the possessions can no longer be precisely determined, but also included the bailiwick rights for the Werden Abbey in the Lüdinghausen area. By this marriage at the latest, a relationship with the Cappenbergers arose, with Adolf II von Berg becoming Vogt of the Premonstratensian Monastery of Cappenberg around 1122 and thus again receiving a considerable increase in power; around this time the Berger also appear as monastery bailiffs of Siegburg .

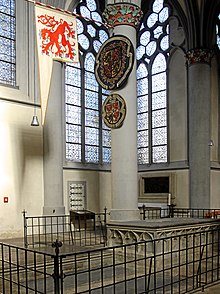

Adolf II built the new castle - Novus Mons - on the Wupper, today known as Schloss Burg, on a previous fortification from the 10th century. The old ancestral castle Berge in Odenthal - Altenberg - Vetus Mons - was abandoned around 1133. The properties around the ancestral castle Berge were handed over to the Cistercians , who built the Altenberg Abbey with a first monastery church there from August 25, 1133 . The very large church, built from the middle of the 13th century, is now called Altenberg Cathedral . The influence and probably also the monetary efficiency of Count Adolf II. Von Berg in the Rhenish-Westphalian area were recognizable from the fact that both his brother Bruno and his son Friedrich became Archbishop of Cologne.

His second marriage to a niece of the Archbishop of Cologne, Friedrich, brought Adolf bailiff right over Siegburg Abbey , which is first attested in 1138/39.

Even though the main focus of Bergisch power was in Westphalia, Adolf II did not fail to extend his rule between Wupper and Sieg. Since this area was almost exclusively owned by the Cologne monasteries and monasteries, Adolf was able to achieve this goal mainly by taking over church bailiffs.

Engelbert I. von Berg

In 1160 the Bergisch domain was divided between Adolf's sons Everhard and Engelbert . This practice of dividing the inheritance - which inevitably leads to a decrease in value - is already common among the Carolingians. Adolf II actually faced a big problem in 1160: he had six sons. If he had to give everyone a share of his land, the Berg dynasty would have lost whatever influence it had gained. His eldest son Adolf died in 1148 off Damascus in the Second Crusade . He had introduced Everhard and Engelbert into the worldly, Friedrich and Bruno into the spiritual life. His youngest son, also Adolf, was only born in 1160 and was therefore probably not entitled to inheritance. Therefore Adolf II was able to divide his county between two sons and thus secure a certain centralization of the influence gained.

Everhard, older than Engelbert, received the Westphalian possessions with the castles Altena and Hövel and the Vogteien Werden, Essen and Cappenberg. This makes it clear that for Adolf II the Rhine-Franconian possessions must have been of lesser value than the Westphalian ones. Engelbert I. von Berg got the Rhine-Franconian inheritance and continued the name Berg in his family. Everhard founded the Altena line; his descendants later called themselves Counts von der Mark .

As a result of the division of the estate, Engelbert was able to focus entirely on the area between the Rhine, Ruhr, Wupper and Sieg. The long-standing favor and friendly relations of the Archbishops of Cologne, his relatives, were of use to him: Archbishop Friedrich II was his brother; with Philipp von Heinsberg he had their grandmother Adelheid von Lauffen. Bruno III, who was only ordained Archbishop of Cologne after Engelbert's death in 1189. von Berg was his half-brother, Adolf von Altena was the son of his brother Eberhard von Altena, i.e. his nephew. Engelbert was married to Margarethe von Geldern .

The center of his dominion was the castle Burg an der Wupper, built by Adolf II. At Engelbert, the possession of Bensberg Castle can be proven, in 1174 Neu-Windeck Castle was added as a (sub) fief of Heinrich Raspe.

Until the seventies of the 12th century Engelbert, as Vogt of the Cologne Severinsstift, succeeded in expanding the domain of Agger and Sülz over the Siegburg Vogtei. The Neuenberg Castle near Lindlar served as the center of the Oberberg regional development (later it became a border fortress to the Gimborn rule ).

The possessions of Severinsstift east of Bensberg, near Hohkeppel and in the Lindlar area were likely to have been under the Bergische Vogtei for the St. Severin Monastery before.

The Allode acquired on the Sieg - for example near Eitorf - as well as the acquired bailiwicks over Bonner Stifts, above all over St. Cassius ( Auelgau ), gave the Bergern the extension of the rule south of the Sieg, which in 1172 through the inheritance of half the rule Saffenberg was expanded.

After losing the Werdener Vogtei and the associated supremacy in the eastern part of the Niederbergischen to his brother Everhard, Engelbert sought to gain influence in the west of the Niederbergischen. More important was the acquisition of the Kaiserswerth Vogtei , where Engelbert replaced the Hardenbergers, who were still called from 1145 to 1158. It was only Engelbert I and his successors who acquired property in Niederbergischen, around Hilden and Haan in 1176 and around Düsseldorf in 1186. Probably in 1189, probably in connection with the Third Crusade of Frederick I Barbarossa, Arnold von Teveren (Tyvern) pledged his entire property on the right bank of the Rhine to Holthausen, Düsseldorf, Buscherhof, Eickenberg near Millrath, Monheim, Himmelgeist, on the banks of the Rhine near Holthausen and on the Anger for 100 marks to Engelbert von Berg - the deposit was never redeemed. In the period that followed, the Counts von Berg, who had become strong and powerful , were able to take over further possessions in this area from some lords and noblemen (including the lords von Bottlenberg , Erkrath and Eller ) who were in financial distress. With this area expansion, Engelbert I probably created the first courts and offices for the administration of his country.

Adolf III. from mountain

The unredeemed pledged goods of the nobleman of Teveren fell to Engelbert's son and successor Adolf III. They are the oldest holdings of the Berg family north of the Wupper. The acquisition of the bailiwick of the Gerresheim monastery brought further power gains . Adolf III. owned farms in Merheim, Mülheim, on both banks of the Rhine between Rheindorf and Zündorf, Buchheim, Lind and Uckendorf. Hückeswagen did not waive all claims from Engelbert I's pledges until 1260; they are probably under Adolf III. already passed to Berg as an allode or fiefdom. His national policy was aimed at securing and developing what had been achieved.

Engelbert II. Von Berg, Engelbert I. Archbishop of Cologne and Count von Berg

As Adolf III. In 1218 he died on the Damiette crusade in Egypt without a son as heir, the Limburg family , into which Adolf's daughter Irmgard had married, asserted its inheritance claim to the entire Bergisch property. Adolf's younger brother, Archbishop Engelbert I of Cologne , feared that the Limburgers, with whom Adolf III. Had disputes, not as faithfully as previously the Berg family would hold the archbishop. Therefore, he rejected the Limburg claims by force of arms and took control of the county of Berg himself as Engelbert II.

With his assassination in 1225, the Bergisch count family ended in this line of descent, since the male line of the Bergisch counts expired with the death of Engelbert II. Berg came to the House of Limburg, which was ultimately able to enforce its inheritance claims.

House Limburg (1225-1348)

The county of Berg now fell as an inheritance via Irmgard von Berg to Heinrich von Limburg , son-in-law of the Bergisch Count Adolf III., And then to his son Adolf IV. Von Berg (r. 1246–1259), who thereby the close ties to the Archdiocese of Cologne further confirmed that he married the sister of the Archbishop of Cologne Konrad von Hochstaden . Adolf IV was the older of Heinrich's sons and, as the firstborn, would have had claims to Limburg, but inherited Berg; the younger brother Walram received the Duchy of Limburg . Under Adolf IV, the city of Remagen was acquired as an imperial pledge in 1228 and, since the imperial pledge was no longer redeemed, remained in the possession of the Berger and their legal successors until it was pledged to Kurköln in 1425 and 1452 .

His son Adolf V (1259–1296) captured the Archbishop of Cologne , Siegfried von Westerburg , in the Battle of Worringen and declared Düsseldorf a city in the same year (1288) . With the victory in the Battle of Worringen, the threat to the existence of the County of Berg, which the Archbishopric of Cologne posed, was finally averted.

He was followed by his brother Wilhelm I (1296–1308). Since no succession had yet been determined in Berg - only the claims from the male lines had the priority of the inheritance - the older brother of Wilhelm renounced the inheritance. Both were provosts in Cologne. Wilhelm I was released from his vows and married Irmgard von Kleve, the marriage remained childless.

Then the inheritance went to Adolf VI. (1308–1348), who was a nephew of Wilhelm I and a son of the late Heinrich von Berg , Herr von Windeck. With a lot of skill in questions of imperial politics, Adolf VI. secure some rights that were granted to him by Ludwig the Bavarian .

He was seen in the entourage of Ludwig both in the election of a king and in the Italian Crusade in 1327 and in the coronation of Ludwig as emperor. Adolf died after 40 years of reign. With him, the Limburg-Berg line became extinct. It left heraldic traces through the Limburg lion , who mutated into the Bergisch lion with a blue crown and weapons . Since Adolf VI. remained childless, he had appointed his sister Margarete and her rightful heirs as his successors on August 16, 1320.

House Jülich (1348–1521)

Berg now fell to the daughter of Adolf's sister Margarete , Countess Margarete von Ravensberg-Berg , who had married Count Gerhard von Jülich-Berg, son of Duke Wilhelm von Jülich , in 1338 . Gerhard, who had become ruler of Ravensberg as early as 1346 through his marriage to Margarete, the heiress of the Grafschaft Ravensberg , ruled Berg from 1348. With his rule, the later union of the territories of Jülich-Berg , which from 1423 when with Rainald von Jülich-Geldern, the Jülich main line died out and was to form an important complex in the Lower Rhine-Westphalian region and a counterweight to Kurköln . Gerhard was able to expand his territory between Wupper and Ruhr by purchasing the Hardenberg estate with the towns of Neviges and Langenberg . After his early death at a tournament in Schleiden in 1360, Gerhard left behind an underage son and two daughters. Count Wilhelm II ruled under the supervision of his mother Margarete von Ravensberg-Berg. Wilhelm acquired the castle and office of Blankenberg, he was in 1377 by Emperor Karl IV . appointed to his secret council and housemates . The friendly relationship continued when Charles's son Wenceslaus succeeded him as the Bohemian and Roman-German king.

The dukes of Jülich-Berg

Count Wilhelm II of Berg and Ravensberg received the duchy of King Wenzel on May 24, 1380 at the Reichstag in Aachen , and the county of Berg was elevated to a duchy. In the same year the duke gave up the castle on the Wupper as his residence, and Düsseldorf became the new seat of government . By choosing Düsseldorf as the capital of the duchy and building a new residence on the Rhine trade route, Wilhelm II wanted to express his new, elevated position in the empire more strongly. In addition, Wilhelm's daughter Beatrix von Berg (1360-1395) became Electress of the Palatinate through marriage in 1385 .

After the death of Duke Rainald von Jülich and Geldern in 1423, his son Duke Adolf VII got the duchies of Jülich and Geldern confirmed. Since Adolf VII, who died in 1437, had survived his son from his first marriage and the second marriage remained childless, the successor fell to the son of his brother Wilhelm, Gerhard II.

Kleve and Mark have been administered jointly since 1461. In 1510 the Klevian heir to the throne married the daughter of the last Duke of Jülich-Berg, which in 1521 led to the union of Kleve-Mark with Jülich-Berg-Ravensberg. Berg remained united with the Duchy of Jülich from then until the beginning of the 19th century . The personal and real union of both territories was also referred to as the Duchy of Jülich-Berg at this time .

In 1484 the office and the castle Löwenburg in the Siebengebirge came through the marriage of Wilhelm III. von Berg and the heiress of the Löwenburg rule, Elisabeth von Nassau, to the Duchy of Berg. In 1500 the duchy became part of the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire .

United Duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg

After the extinction of the Jülich-Bergisch house (1521), the rulers of the Duchy of Kleve and the County of Mark from the noble family von der Mark , one of the two Westphalian branches of the old Counts of Berg, followed. They united the duchies of Jülich, Kleve, Berg, temporarily also Geldern and the counties of Mark and Ravensberg as well as the dominions of Ravenstein and Lippstadt as united duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg in one hand. Three dukes ruled from this house, the first was Johann the Friedfertige from 1511 in Jülich, Berg and Ravensberg and from 1521 also in the paternal inheritance, the Duchy of Kleve, the County of Mark and the condominium Lippstadt. Johann was engaged to the heiress of the Jülich family at Schloss Burg as a child . He was succeeded by William the kingdoms of the 1539th On October 31, 1583, he issued the ducal order that introduced the Gregorian calendar in the duchy. Between 1538 and 1543 he was also Duke of Geldern , which he lost to the Emperor during the war, to whom he had to submit and whose relatives he had to marry. The eldest son of Duke Karl Friedrich died on an educational trip through Europe in 1575 in Rome. There he stayed as the Pope's guest of honor at the Christmas celebrations of the Holy Year 1574. He was in Santa Maria dell'Anima across from Pope Hadrian VI. buried. After the death of Karl Friedrich in 1592, Johann Wilhelm the Good-natured came to the throne as the third and last ruler of this old Bergisch-Brandenburg house. Johann Wilhelm had been Prince-Bishop of Münster from 1574 to 1585 and had resigned his church offices after it was established that his father would no longer have any further heirs. He married twice, first in 1584 to Jakobe von Baden , who was murdered in 1597 while he was mentally deranged, and later to Antonie von Lothringen . Despite all attempts to prevent the house from becoming extinct, both marriages remained childless, and illegitimate children are also not known.

After the extinction of the male Duke strain of the mark in 1609 it came to the Jülich-Cleves succession dispute , which ended with the succession in Jülich and Berg the Wittelsbach house Neuburg fell.

After the inheritance of 1614

Under Wolfgang Wilhelm, the Duchy of Berg was administratively divided (around the 1640s) into 37 tax districts (19 offices, 8 freedoms, 10 cities: Düsseldorf, Lennep, Wipperfürth, Ratingen, Rade vorm Wald, Solingen, Gerresheim, Blankenberg, Siegburg, Elberfeld) . The country chancellery was replaced by the Jülich-Bergischer Hofrat .

From 1652 to 1679 Philipp Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg was Duke. His son and successor Johann Wilhelm II (1679–1716), Elector Palatinate (1690–1716), is remembered to this day in his residence city of Düsseldorf and in the Bergisches Land as “Jan Wellem”. The loss of Heidelberg Castle was replaced by Schwetzingen Castle as a summer residence.

From 1708, Erich Philipp Ploennies created the Bergische Landaufnahme of the Berg territory, which was published in 1715 under the title Topographia Ducatus Montani (Topography of the Duchy of Berg).

Charles III Philipp von der Pfalz (1661–1742) took over the government after the death of his older brother. From 1720 he expanded Mannheim as a residence and built the Mannheim Palace .

In 1742 the land came to the Elector Karl Theodor from the Sulzbach line, became a part of the Electoral Palatinate Bavaria in 1777 and, after Karl Theodor's death in 1799, went to Duke Maximilian Joseph von Pfalz-Zweibrücken , who later became King of Bavaria. He left the Duchy of Berg on November 30, 1803 to his brother-in-law, Duke Wilhelm in Bavaria, as an appanage , but retained sovereignty. Wilhelm resided as governor in Düsseldorf.

The Napoleonic Grand Duchy of Berg (1806–1813)

On March 15, 1806, King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria ceded his Duchy of Berg to Napoleon . Kurbayern committed itself to this in the Treaty of Schönbrunn in 1805 in exchange for the Principality of Ansbach . On the same day, Napoleon transferred sovereignty over the duchies of Berg and Kleve to his brother-in-law, the French prince Joachim Murat , who thereby also became a German imperial prince , albeit temporarily . The territory of the Duchy of Kleve, ceded by Prussia , only affected the part on the right bank of the Rhine ; the left-bank part was already since 1797/ 1801 French territory. Murat took his land in Cologne on March 19, 1806, initially as Duke of Kleve (Cleve) and Berg, and eight days later received homage from the estates in Düsseldorf. Later the area was expanded territorially. In addition to the Kingdom of Westphalia , the Grand Duchy of Berg was to become a model state and model for the other states of the Rhine Confederation . There were reforms in particular in the administration , the legal system as well as economic reforms and agricultural reforms. Napoleon's customs policy caused massive economic problems. The drafts into the military also caused displeasure. This erupted in January 1813 in the Knüppelrussen uprising .

Soon after the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig (October 1813), the Grand Duchy effectively dissolved. From 1813 to 1815, the General Government of Berg was set up as an interim administration for the Grand Duchy, which still existed legally . Most parts of the country, together with the Grand Duchy, fell to Prussia through Article XXIV of the Main Act of the Congress of Vienna . It formed the province of Jülich-Kleve-Berg with the administrative seat of Cologne along with the other Prussian possessions on the left and right banks of the Rhine .

The title "Grand Duke of Kleve and Berg" passed to the King of Prussia and the House of Prussia .

coat of arms

Coat of arms until 1225

The historical coat of arms of the Counts of Berg was initially a black pinnacle bar. Only since 1210 has the rider's seal Adolf III. the coat of arms of the first Counts of Berg (two black alternating battlements in silver) attested (e.g. still contained in the coats of arms of the Rheinisch-Bergisches Kreis and the city of Hilden and the city of Leverkusen ). The former city of Opladen also had this pinnacle bar in its coat of arms until it merged with the city of Leverkusen (December 31, 1974). The alternating crenellated beam comes from the brothers Gerhard and Giso von Upladhin, who were landlords in Opladen in the early 13th century and who, as castle men of the Counts of Berg, had their older coat of arms. Engelbert II. Von Berg, as Archbishop Engelbert I of Cologne, placed this first coat of arms on the archbishop's coat of arms (black cross) as a shield holder.

From this coat of arms a group of coats of arms formerly Bergischer ministerial families emerged, to which u. a. the present-day barons of Bottlenberg (a black pinnacle bar in silver), the Counts of Nesselrode (a silver pinnacle bar in red) and the Princes of Quadt (two silver pinnacle bars in red) belong.

Heraldic shield of the former city of Opladen with the historical double pinnacle beam

Coat of arms of the Rheinisch-Bergisches Kreis

Coat of arms of the city of Bergisch Gladbach

Coat of arms of the city of Hilden

Coat of arms of the city of Leverkusen

Coat of arms from 1225

The coat of arms of the Bergisches Land shows, according to the Bergisch colors, on a white background the red, double-tailed Bergisch lion with claws, tongue and a crown in blue, which goes back to the House of Limburg (see above) . Even today, the Bergische Löwen have several cities and districts in their coat of arms .

Creation of the coat of arms with the Bergisch lion:

Heinrich von Limburg, who came into the possession of the County of Berg through his marriage to the Bergish heir daughter Irmgard, kept the red, double-tailed and crowned Limburg lion on a golden background, while his eldest son and successor Count Adolf IV. Von Berg (1246– 1259) carried the same coat of arms, increased by a five-stitched tournament collar on the raised bar, which is still included in the coat of arms of the city of Wipperfürth .

The following Bergisch counts kept the tournament collar until 1308. Count Adolf VI. von Berg was the first Bergisch sovereign who wore the well-known Bergisch coat of arms of later times, derived from his father Heinrich, Herr zu Windeck , without a tournament collar: the red, blue-armored, blue-crowned and double-tailed standing lion.

The Bergische Löwe can still be found in many district and municipal coats of arms, here is a selection:

Office constitution: offices and freedoms - law and administration, Bergischer nobility

Altbergisches administrative system - origin and constitution of the Bergisch offices

Almost regularly one finds in documents of the Bergisch as well as other Lower Rhine territories the offices of the Middle Ages related to a castle , which forms the center of the administration for the respective office or which originally formed it. For Berg, this connection between castle and office can be demonstrated by the fact that for all offices of the duchy, with one exception ( Amt Miselohe ), a castle or at least a fortified place, which was probably originally a castle, can be proven as the center. The offices formed after the respective castle as a center in such a way that initially small castle districts were gradually expanded to the office. In the character of the castle as the center of a district of sovereign estates, fiefdoms and manorial rights, the real reason for the expansion of the citizen administration to the official administration can be found.

The administrative districts were formed around the middle of the 14th century. They served the tighter administration and emerged from the efforts of the sovereigns, which began in the 13th century, to unite the scattered territories and to achieve full sovereignty.

As the basis for a uniform regulation of general administrative sovereignty in the county of Berg, the constitution of offices remained decisive for more than four centuries.

In their later full formation, the offices were the districts directly subordinate to the central administration, in which the local financial and police administration as well as the maintenance of public security converged entirely, the judicial system at least partially.

Three officers were responsible for the management of the offices, the magistrate or judge, the waiter or treasurer and the two parent bailiff .

The highest official in the office was the bailiff, who was of aristocratic descent, was personally appointed by the sovereign and had his official seat in a castle that was mostly owned by the sovereign. The official seat could also be the bailiff's castle. He had three main powers, an administrative-financial, a military-police and an originally limited, but gradually increasing in scope and importance judicial - he was responsible for law and order within the boundaries of the office. Subordinate to the bailiff was the mayor as head of administration and jurisdiction, who also chaired the court hearings. The third highest official was the rent master (also called waiter), who was responsible for the collection of taxes, the administration of the estate and the court fees and fines.

The announcement and execution of the official decrees in the individual parishes was always done by the Scheffen. The court backed the rulings.

Altbergisches judicial system - main court, regional court, court court, messenger office, sending court

The basis of jurisdiction in the early Middle Ages was Roman law . Documents and judgments were made in Latin until the middle of the 13th century. One of the first documents in German was from 1262. While Roman law was replaced by a new German jurisdiction as early as the beginning of the 13th century in other German areas, this was not the case in the Berg area until a little later. This peculiarity was confirmed by the German rival king Wilhelm in a document issued in Kaiserswerth in 1248 . From the middle of the 13th century, a new type of jurisdiction also developed in the Bergisches Land. Since the 12th century at the latest, the Count's Court in Kreuzberg near Kaiserswerth in the Angermund office was responsible for all matters; but now lay judges' courts were established which were responsible for all crimes except death-worthy crimes such as theft, manslaughter and desecration. These were initially still negotiated in Kreuzberg. The law or knight book , in which the Bergisch judicial system is described in the 14th century, has been handed down.

Main course - upper course

The Bergisch jurisdiction was based on a hierarchy of consultation courts. If a lower court was unable to reach an agreement on a legal issue, the competent court of consultation was called upon. This made a recommendation to which the lower court was not bound in its subsequent decision. In this sense, the main courts took precedence over the regional courts, with the dubious legal cases being submitted to the main courts for consultation. The mayor presided over the judges of the higher court. These legal cases were only announced by the regional courts after the decision of the higher court. The appellation was made for all dishes to the Duke in Düsseldorf.

Main regional and knight court Opladen

The highest court of consultation was what is known in recent literature as the main regional and knight court in Opladen ; in historical documents it was also referred to as the knight's court , high court and supreme main court . Until 1559, this court had its seat in the centrally located Opladen, then as Jülich-Bergischer Hofrat in Düsseldorf . In addition, the knight's court was also the court for the Bergisch nobility and the meeting place of the knight and state parliament, in which the Bergisch state estates organized their self-administration. In return for their privileges, the knighthood was obliged to serve with horse and armor when the ruler was called up.

The main court in Porz received its legal instruction at the knight's court in Opladen, which was also presided over by the mayor of Porz.

In addition to catching in the wild (hunting and fishing law) as well as extensive duty and tax exemption, these free knight feudal bearers also had a special place of jurisdiction.

district Court

The regional courts were located in the parishes; they were responsible for the jurisdiction of the honors, with each Honschaft a Scheffen (Schöffen). The regional courts were responsible for all legal cases of "sovereignty, violence, guilt and debts", ie criminal cases or controversial inheritance cases. They could also pass death sentences, but most of them were handed over to the main court.

The negotiations before the regional courts have been carried out since 1565 according to the new Jülich-Bergisch legal, fiefdom, court clerk, brigade, police and reformation order. Judges, Scheffen, clerks and messengers were sworn in. Legal counsel was given to the defendants.

Court court

The court courts were responsible for civil legal matters, in particular inheritance in the event of death (whereby the law of real division was valid in the Bergisches Land ), alienation of property through sale, donation, division, exchange, pledging or encumbrance; so they had the task of today's local courts. The court courts go back to the time of the first conquest of the land and the establishment of the royal corpses. They originally comprised the feudal association of a Fronhof and had the task of safeguarding its rights.

Messenger office

The regional courts subordinate to the offices were divided into messenger offices, which mostly corresponded to the respective parish. Each messenger office had a messenger or treasure messenger. These were not considered state officials and received no allowance from the ducal treasure, had to belong to a respectable family and were sworn in for their office. However, the messengers were assured a certain sum from the subjects, which had to be collected with the "treasure". The messenger collected the taxes, the fines and the fees and delivered them to the "waiter".

Sending court

The Sendgericht , also called Send, was a spiritual court that existed alongside the secular court and whose origins go back to the first Christian centuries. For Wiehl ( Reichsherrschaft Homburg ) as well as for the Bergisch parish Much there is evidence of a sending court. The dukes of Berg protected the broadcast court and insisted that it be held regularly. Later ecclesiastical jurisdiction was increasingly restricted by secular power and gradually lost its powers. At first the bishop presided over the annual visitations of the sending court, in the 12th century the archdeacon or as a representative of the dean. From the 13th century it was customary for the pastor to hold the Sendgericht himself, and from the 17th century onwards, Sendschöffen in the rural parish Christianity Siegburg are also called. The Sendgericht was primarily a reprimand and moral court and pursued offenses that could also be the subject of a spiritual process: u. a. Heresy , adultery , unchastity, usury , quarrels and the like. The court was able to impose material sentences as well as corporal and prison terms.

Old Bergisches Steuerwesen - Tithe Law - Coin Law - Mining Law - Customs

inch

Customs duties can be proven in the county of Berg as early as the 13th century. Count Wilhelm II. (1360–1408) declares in a document from 1386 that there are “Zwenn tariffs, in and through dat lant van dem Berghe”, i.e. only the import and transit tariffs, which are twice the import tariffs. The export duty was later also imposed. Initially, the duchy was surrounded by customs stations at all borders, but although Jülich and Berg were subordinate to the same duke, there was no coin or customs unit. In 1398, Duke Wilhelm von Berg obtained permission from King Wenzel to set up two new land tariffs - one on Lennep, the other on Wipperfürth. As known from the inquiry made in 1555, Lennep had a beizoll in Wermelskirchen. In the same year, the city of Cologne complained to the Duke about the new customs at Wermelskirchen.

Towards the end of the 15th century, the Duchy of Berg was also riddled with customs posts inside, as carters, drovers, horsemen and farmers knew how to bypass the prescribed roads to the customs houses and smuggle the goods through secondary and secret routes.

In earlier times the levied land tariffs were mainly used for the maintenance and establishment, expansion and safety of paths, bridges and footbridges. Around 1500 the duke's duty for a horse was 8 Albus, also for a cartload, and twice that amount had to be paid for a cartload.

taxes and expenses

The income of the sovereigns consisted of "tariffs", "tithes", "Kürmut", "treasure", "interest" and other "inclines". However, this income was not enough to cover all state expenses.

As a result, the sovereigns saw themselves forced to “Beden” (requests), funds that had to be approved by the state for various administrative expenses. This special tax, a voluntary levy in earlier years, was usually levied in the autumn after the harvest.

In earlier times taxes were intended for extraordinary expenditure on war; in later centuries they were used for ordinary national defense as well as for the maintenance of security and general "retirement" (order).

The church property, the fiefdom of the feudal people as well as the property of the knighthood and the nobility were free of duties and taxes . Freedoms could be partially or fully exempt. The actual knight's seats ( Bergische knight's seats ) were free of taxes, even if they were not inhabited by the knight. Only the noble free goods given as fiefs were taxable through the tenants. The clergy and knighthood were therefore not allowed to acquire "treasures" from other citizens in order to avoid tax disadvantages for the country.

The taxes were proposed by the sovereign to the assembled estates and approved by a majority of votes.

Taxes:

- The oldest is probably the communicant tax , later called personal tax (personal tax). The poor were exempt from tax.

- The pension tax or wealth tax: everyone who had a pledge had to give up the tenth pfennig, and later the fourth pfennig.

- Property tax: This was paid on land and houses.

- The cattle tax (horse 1 Rtlr., Ox 40 stüber , cow 30 stüber etc.)

- The profit and trade tax: This tax was paid by the dispossessed, the "helpers, tenants" and feudal people and was based on the size of the cultivated area. Even the shepherds, workers and servants had to pay taxes on their income.

- The consumption tax: It was an indirect tax and could therefore reach an oppressive level. Wine, beer, vinegar, herrings, salt, also oil, pipes, playing cards, oil, butter, etc. were taxed.

- The war tax: As a rule, this was only paid on land and did not arise in the Bergisches Land until the Thirty Years' War to create a standing army.

Tithe - tithe right

Tithe was an Altbergian type of taxation. It consisted of the tenth part of all agricultural products having to be given up. The great tithe was given from corn and cattle; the small tithe was paid for vegetables, herbs and fruits as well as for slaughtered small farm animals.

The recipients of the tithe were mostly aristocrats and churches. In return, they had to maintain the parish church, keep "Zielhvieh" (breeding cattle), prepare cart, plow, harrow and malt, give a gravel and clay pit - all for the free use of those who paid tithing.

Bergregal - Bergrecht in the Duchy of Berg - Jülich-Bergische Bergordnung

In the 13th century at the latest, the Counts of Berg began to dig individual pits, such as B. to bring the silver mine on the former Reichshof Eckenhagen into their possession. Emperor Karl IV. (1347–1378) established the sovereign rights of the sovereigns in 1356: mountain and salt shelves , customs duties , right to mint a . a. The right to dig up the treasures of the land was thus one of the sovereign's regalia. In the Bergisch departments of Steinbach, Porz with Bensberg and Windeck, mining became more important around the turn of the 16th century, but came to a complete standstill with the Thirty Years' War.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the search for mineral resources was more done by private individuals than by the state. The reasons for mining were old tunnels that had been in operation centuries ago, consultation with people who knew the geological soil conditions, or one relied on luck. The application for granting the courage was submitted to the mountain master as the representative of the sovereign and the Bergisch mountain court , which then issued the mother with the courtesy certificate. Over the next two weeks, the mother had to "bare the corridor" and have it inspected by the mountain master. Usually the certificate was issued for half a year, for which time the sovereign received quarter money : 10 Albus for every treasure trove and measure , 20 Albus for every (machine) Puch and washing facility. The free time could be extended upon request. If the mine was abandoned by Muter or if he did not comply with the mining law obligations, the mine was again at the free disposal of the sovereign.

Upon request, the presumption was followed by the lending after approval and examination of the mining court, after a previous inspection of the relevant pit and the drafting of a report by a commission of the mountain jury . If no objections were raised, the owner or the union was enfeoffed with a treasure trove and a certain number of measurements according to the dimensions of the district and thus entered in the trade union register as the fief of the mine.

The obligation of the feudal bearer to the sovereign consisted in the submission of the tithe and the quatember - or term money. For the first three years the feudal bearer enjoyed tithe freedom if the mine remained without profit. The amount of the quarter money for each treasure trove and each measure was 20 albus and had to be paid quarterly.

Münzrecht - Bergische coins

The originally exclusively royal right to mint coins in the Holy Roman Empire expanded from around 1062 to clerical princes and, a short time later, to secular princes. Taking advantage of the political situation, Adolf I will have done the same as his Cologne neighbor and will have acquired the right to mint coins; It is also possible, however, that as Vogt von Werden and Siegburg he used the right to mint these monasteries. The people of Cologne welcomed the issue of Bergisch money, because Adolf I had a penny struck which, except for the inscription, is a replica of the Cologne money, but was more comprehensive, i.e. more valuable than the Cologne money. The coin was made of silver and weighed about 1.4 grams.

Adolf II had a 1.6 gram pfennig struck, which was a replica of the pfennig belonging to Archbishop Bruno II of Cologne , his brother, and which may have come from the same die cutter. Engelbert I also copied such Cologne pfennigs, while his son Adolf III. no coins are known.

Engelbert II had coins struck as Archbishop of Cologne, but none of them are known as Count von Berg. There are also no known coins from Heinrich von Limburg.

During the time of Engelbert II, Emperor Frederick II granted great privileges on April 26, 1220, called Constitutio cum principiis ecclesiasticis, through which the ecclesiastical rulers a. a. received the coin rack. In 1232 the secular sovereigns also received the right to mint in the statute in favorem principum .

Adolf IV struck pennies again, which were modeled on the Cologne coinage. There was a dispute between the citizens of Cologne and the archbishop over the Bergische coins in 1258. The reverse of Adolf IV's coins bore the name of Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden . The mint was in "Wielberg" ( Wildberg ). There were Bergische silver mines there, other mints were in the neighboring countries. The citizens of Cologne not only demanded a ban, but also the destruction of the mints, since the coins included types of lower quality. First of all, the archbishop compared himself to the citizens of Cologne in the "Großer Schied". When the complaints persisted in the following year, he dismissed the entire council, with the exception of alderman Bruno Crantz.

Count Adolf V received from King Rudolf in a document dated March 26, 1275 the right to permanently move the mint, which had been in operation in “Welabergh” (Wildberg) from ancient times, to “Wippilvordia” ( Wipperfürth ), which means that this document gives the right to mint the Bergische Count was confirmed.

Adolf had pfennigs and quadruplets (quarter pfennigs) struck in Wipperfürth, which show the inscription “Comes de Monte” or “ADOLFUS COMES”. The name of the mint "WIPPERVORDE CIVITAS" or "MONETA WIPPERVERDE" appears on the reverse. These coins are no longer imitations.

No coins are known of his successor Wilhelm I; but he will have received the new right to mint coins. Adolf VI. has a coin of 2½ pfennigs minted, it bears the inscription "WIPPERWRDENS DENARI". Another coin, a “Turnose”, minted after 1326, bears the inscription “TURONUS CIVIS, TERRA DE MONTE, TURONIS DE MONTE, ADOLPUS COMES”. In 1326, Adolf received the so-called Great Turnosenprivileg from King Ludwig the Bavarian.

The mint in Wipperfürth will have been closed around 1350. The last piece seems to have been a double schilling by Gerhard I, which is labeled "Moneta (Mint) Wipperfürth". A new mint had already emerged in Cologne-Mülheim . Margarete von Ravensberg-Berg (1360–1361) coined “Sterlinge” in Ratingen and first used the German language in the legend “VROWE VAN DEN BERG”.

Count Wilhelm II minted “Sterlinge”, “Witte”, “Denare”, “Turnosen”, “Weißpfennige” and “Heller” in Ratingen , Mülheim am Rhein, Lennep and Gerresheim. A “Gulden”, probably minted in Mülheim am Rhein, shows a Jülich-Bergisch shield with the writing “WILHELM COMES DE MONTERA” as Count von Berg and Ravensberg . Other later Bergisch coins are “Weißpfennige”, “Gulden”, “Heller”, “Bausch”, “Lübische”, “Albus” and “Schillinge”.

After 1437 Gerhard II struck a silver coin of 1 Heller, diameter 14 millimeters, with a weight of 0.2 g. The outer ring is not flat, but arched as a hollow ring, presumably attached to leather and has a very good grip. The middle shows the quartered shield with the lions of Jülich (actually black on gold) and Berg (red on silver) and in the middle the Ravensberger rafters.

From 1513, "Guldengroschen" were minted as silver coins with a diameter of 43 to 44 millimeters and a weight of 30 grams, which from 1530 are called Thaler. The first Thaler in Bergisch is struck around 1540. In 1636, Wolfgang Wilhelm had the first Bergisch ducat minted, during which time the guilders became "silver pieces". After that, coins were also issued as fractions, in 1712 1/16 gulden = 1/24 thaler and 1/8 gulden = 1/12 thaler. In 1718 a silver coin of 24 "Kreuzers" = 32 "fat men" was minted and in 1719 a silver coin of 20 "Kreuzers" = "26 fat men". In 1732 the "Karolin" came up and in 1736 the "Stüber". The "Konventionsthaler" was first minted in 1765 in the Bergisches Land. In 1802 Maximilian Joseph struck the first " Reichsthaler ".

Offices

The duchy was administratively divided into offices and several subordinates. The number of offices changed due to the enlargement and change of sovereignty.

The process of forming offices began around the middle of the 13th century and came to an end before September 9, 1363, when the Bergisch offices were first listed in a sovereign bond. These eight offices are still considered as the eight main offices of the Bergisches Land alone in lever lists from the first third of the 15th century. These were the offices of Steinbach , Angermund , Mettmann , Solingen , Monheim , Miselohe , Bornefeld and Porz-Bensberg .

A map made by Erich Philipp Ploennies in 1715 reveals 16 offices. In 1789 the duchy finally consisted of the offices of Angermund , Beyenburg , Blankenberg , Bornefeld-Hückeswagen , Elberfeld , Herrschaft Broich , Herrschaft Hardenberg , Löwenburg , Amt (Unteramt) Lülsdorf , Mettmann , Miselohe , Monheim , Porz , Solingen , Steinbach and Windeck .

Cities and Freedoms

The name freedom is already in use in the 14th century; it was never given to an open place. Essential features are fastening and tax-free.

Cities were granted special rights by the sovereign, either out of special favor or friendship, combined with exemption from taxes. A certificate was issued by the sovereign in which the privileges were precisely defined and thus confirmed. This could also involve obligations for the citizens that the sovereign laid down in a document. This gave rise to the name Freiheit, which is still used in many street names today , for many Bergisch cities .

As an example of the legal term freedom , the special rights of freedom Mülheim are listed here. Count Adolf VI. 1322 granted Mülheim am Rhein freedom from all taxes and services, as well as the right to appoint a lay judge to the higher court. Mülheim was also given the right to have its own court, where goods, market items, bread, wine, contracts, wills, and changes of property were negotiated. The count gave the freedom of Mülheim the preference and freedom that no one was allowed to touch their goods and people (immunity).

"... We also permit and show our special favor to the city of Molenheym that neither we nor any of our civil servants or civil servants should take horses, wagons or carts for any journey or for our use, or have them taken, unless, that we receive this approved at our request ... "

At the request of the citizens, these freedoms could be renewed, confirmed or extended to other rights by the sovereign. Between 1322 and 1730, Mülheim received a princely confirmation of its special rights twelve times, in 1652 market rights for three markets, and in 1714 commercial rights for traders. Thus, the special rights (freedoms) contributed to the well-being of the citizens, to the enlargement and strengthening of the cities and thus ultimately also to the advantage of the sovereignty.

Cities held a special position in the county of Berg and in the later duchy. Düsseldorf, Lennep, Ratingen and Wipperfürth were represented in the Bergisches Landtag and were considered to be capital cities , Radevormwald, Solingen, Gerresheim, and Blankenberg, Elberfeld and Siegburg with city rights. The freedoms were Bensberg , Mülheim am Rhein, Wesseling, Gräfrath, Mettmann and Hückeswagen as well as Angermund and Monheim.

In addition to the offices, the Duchy of Berg included the cities and freedoms of Barmen , Beyenburg , Blankenberg , Burg an der Wupper , Düsseldorf , Elberfeld , Gerresheim , Graefrath , Hückeswagen , Lennep , Mettmann Office , Monheim , Mülheim am Rhein , Mülheim an der Ruhr , Radevormwald , Ratingen , Siegburg , Solingen , Wesseling and Wipperfürth .

City charter granted by the Bergische Counts and Dukes until 1806

-

Wipperfürth (probably 1217, confirmed 1222)

Wipperfürth (probably 1217, confirmed 1222) -

Lennep (1230)

Lennep (1230) -

Ratingen (December 11, 1276)

Ratingen (December 11, 1276) -

Düsseldorf (August 14, 1288)

Düsseldorf (August 14, 1288) -

Radevormwald (between 1309 and 1316)

Radevormwald (between 1309 and 1316) -

Mülheim am Rhein (1322)

Mülheim am Rhein (1322) -

Solingen (1374)

Solingen (1374) -

Mettmann (1424)

Mettmann (1424) -

Elberfeld (1610)

Elberfeld (1610) -

Ronsdorf (1745)

Ronsdorf (1745)

Cities with city charter prior to acquisition by Berg

-

Blankenberg (1245)

Blankenberg (1245) -

Bergneustadt (May 13, 1301). Already pledged from Berg to Mark in 1273, since 1301 a town in the Mark region.

Bergneustadt (May 13, 1301). Already pledged from Berg to Mark in 1273, since 1301 a town in the Mark region. -

Siegburg (before 1182)

Siegburg (before 1182)

Honors

The lowest communal administrative unit in the Duchy of Berg was the honnships .

Nobility - Bergischer nobility

The nobility held a special position in the territorial rulers. Originating from the geographical area itself, its members were initially part of the service aristocracy and were dependent on the sovereign or other princes. They soon played an important role in the higher administration of the territories, enjoyed tax exemption, their own court and were represented in estates. The Bergisch nobility mostly had fortified knight seats as residences, which can still be proven in many parts of the country and are also known as aristocratic seats .

List of the rulers of Berg

Count

House mountain

- Adolf I. (until 1106)

- Adolf II (1106–1160)

- Engelbert I (1161-1189)

- Adolf III. (1189-1218)

- Engelbert II. (1218-1225)

- Henry IV. (1225-1246)

- Adolf IV (1246–1259)

- Adolf V. (1259-1296)

- Wilhelm I (1296-1308)

- Adolf VI. (1308-1348)

House Jülich-Heimbach

- Gerhard (1348–1360), also Count von Ravensberg

- Wilhelm II. (1360–1408), from 1380 duke, 1360–1395 also count of Ravensberg

Dukes

House Jülich-Heimbach

- Wilhelm II. (1380-1408)

- Adolf VII. (1408–1437), since 1423 also Duke of Jülich

- Gerhard (1437–1475), also Duke of Jülich and Count of Ravensberg

- William III. (1475–1511), also Duke of Jülich and Count of Ravensberg

- Johann der Friedfertige (1511–1539), also Duke of Jülich and Count of Ravensberg, since 1521 also Duke of Kleve and Count of the Mark

- Wilhelm V der Reiche (1539–1592), also Duke of Jülich and Kleve, Count of Ravensberg and von der Mark

- Johann Wilhelm I (1592–1609), also Duke of Jülich and Kleve, Count of Ravensberg and von der Mark

House Wittelsbach (Pfalz-Neuburg line)

- Wolfgang Wilhelm (1614–1653), also Duke of Jülich and Pfalz-Neuburg

- Philipp Wilhelm (1653–1679), also Duke of Jülich and Pfalz-Neuburg

- Johann Wilhelm II. (1679–1716), also Duke of Jülich, since 1690 also Elector of the Palatinate and Duke of Palatinate-Neuburg

- Karl Philipp (1716–1742), also Elector of the Palatinate and Duke of Palatinate-Neuburg

House Wittelsbach (Pfalz-Sulzbach line)

- Karl Theodor (1742–1799), also elector of the Palatinate and Duke of Pfalz-Neuburg, since 1777 also elector of Bavaria

Wittelsbach House (Pfalz-Birkenfeld-Bischweiler line)

- Maximilian Josef (1799–1806), also Elector of Bavaria; last reigning Duke of Berg

See also

literature

- Path order for the Duchy of Berg. Düsseldorf 1805 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf ).

- Two geographical descriptions of the Duchy of Berg from the first third of the 18th century. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. Vol. 19, 1883, ISSN 0067-5792 , pp. 81-170, digitized edition .

- Georg von Below : The state constitution in Jülich and Berg. 3 volumes. Voss, Düsseldorf 1885-1891 (new print. Scientia-Verlag, Aalen 1965).

- Johann Bendel : The city of Mülheim am Rhein. History and description, sagas and tales. Self-published, Mülheim am Rhein 1913 (facsimile print. Scriba Verlag, Cologne 1972).

- Alexander Berner: Crusade and regional rule. The older counts of Berg 1147–1225. Böhlau, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-412-22357-1 .

- Nicolaus J. Breidenbach (ed.): The court in Wermelskirchen, Hückeswagen and Remscheid from 1639 to 1812. Texts and reports from the court minutes and official files of Bornefeld-Hückeswagen (= Bergische Heimatbücher. NF Vol. 3). Breidenbach, Wermelskirchen 2005, ISBN 3-9802801-5-2 .

- Nicolaus J. Breidenbach: When King Wenzel granted customs. As early as 1398: A Landwehr with a jump in Niederwermelskirchen. In: Rheinisch-Bergischer Calendar. Vol. 57, 1987, ISSN 0722-7671 , p. 48.

- Albrecht Brendler: On the way to the territory. Administrative structure and office holder of the County of Berg 1225–1380 . Dissertation, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn 2015.

- Helmuth Croon : Stands and taxes in Jülich-Berg in the 17th and mainly in the 18th century (= Rheinisches Archiv. Vol. 10, ISSN 0933-5102 ). Röhrscheid, Bonn 1929.

- Toni Diederich : Rheinische Städtesiegel (= Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Landschaftsschutz. Yearbook. 1984/85). Neusser Druckerei und Verlag, Neuss 1984, ISBN 3-88094-481-4 .

- Jörg Engelbrecht: The Duchy of Berg in the Age of the French Revolution: Modernization Processes Between the Bavarian and the French Model . Schöningh, Paderborn 1996.

- Kurt Erdmann: The Jülich-Bergische Hofrat until the death of Johann Wilhelm (1716). In: Düsseldorfer Jahrbuch. Vol. 41, 1939, ISSN 0342-0019 , pp. 1-121.

- Hans Fahrmbacher: Prehistory and beginnings of the Electoral Palatinate Army in Jülich-Berg 1609–1685. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. Vol. 42, 1909, pp. 35-94.

- Bastian Fleermann: Marginalization and Emancipation. Everyday Jewish culture in the Duchy of Berg 1779–1847 (= Bergische Forschungen. Vol. 30). Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 2007, ISBN 978-3-87707-702-3 (At the same time: Bonn, University, dissertation, 2006).

- Hans Goldschmidt : Spiritual property and spiritual tax in the Bergisch offices of Misenlohe, Mettmann, Angermund and Landesberg. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. Vol. 45, 1912, pp. 156-171.

- Hans Goldschmidt: The estates of Jülich-Berg and the sovereign power 1609–1610. In: Journal of the Aachen History Association. Vol. 34, 1912, pp. 175-226.

- Hans Goldschmidt: War sufferings on the Lower Rhine in 1610. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. Vol. 45, 1912, pp. 143-155.

- Franz Gruss: History of the Bergisches Land. Gruss, Leverkusen 1994, ISBN 3-930478-00-5 .

- Anton Jux, Josef Külheim : Homeland book of the community Hohkeppel. For the millennium celebration 958–1958. Hohkeppel municipality, Hohkeppel 1958.

- Hans Martin Klinkenberg : The political fate of the Bergisches Land from the elevation to the duchy to the integration into the Prussian state. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. Vol. 80, 1963, pp. 33-45.

- Axel Kolodziej : Duke Wilhelm I. von Berg (1380-1408) (= Bergische Researches. Vol. 29). Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 2005, ISBN 3-87707-639-4 (at the same time: Bonn, University, dissertation, 2003).

- Thomas R. Kraus : The emergence of the sovereignty of the counts of Berg up to the year 1225 (= Bergische Forschungen. Vol. 16.) Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 1981, ISBN 3-87707-02-4 , pp. 16-29 ( At the same time: Bochum, University, dissertation, 1977/78).

- Hansjörg Laute: The Lords of Berg. On the trail of the history of the Bergisches Land (1101–1806). Boll, Solingen 1988, ISBN 3-9801918-0-X .

- Victor Loewe: A political-economic description of the Duchy of Berg from the year 1740. In: Contributions to the history of the Lower Rhine. Yearbook of the Düsseldorf History Association. Vol. 15, 1900, ZDB -ID 300198-2 , pp. 165-181, digitized .

- Rolf-Achim Mostert: Wirich von Daun Graf zu Falkenstein (1542–1598). An imperial count and the Bergisch state in the tension between power politics and denomination. Düsseldorf 1997 (Düsseldorf, Heinrich Heine University, dissertation, 1997).

- Rolf-Achim Mostert: The Jülich-Klevian regimental and succession dispute - a prelude to the Thirty Years War. In: Stefan Ehrenpreis (ed.): The Thirty Years War in the Duchy of Berg and its neighboring regions (= Bergische Forschungen. Vol. 28), Neustadt an der Aisch 2002, ISBN 3-87707-581-9 , pp. 26-64.

- Karl Oberdörfer: The old parish Much. Rheinland Verlag, Cologne 1923.

-

Erich Philipp Ploennies : Topographia Ducatus Montani . (1715) (= Bergische Forschungen. Vol. 20). Edited and edited by Burkhard Dietz. Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 1988;

- Volume 1: Country Description and Views. ISBN 3-87707-073-6 ;

- Volume 2: Maps. ISBN 3-87707-074-4 .

- Theodor Rutt: Overath. History of the community. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1980, ISBN 3-7927-0530-3 .

- Gerold Schmidt: The historical contribution of the Rhineland to the emergence of North Rhine-Westphalia. For the 50th anniversary of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. In: Rheinische Heimatpflege . New episode. Vol. 33, 1996, ISSN 0342-1805 , pp. 268-273.

- Johann Schmidt (Ed.): Geography and history of the Duchy of Berg, its dominions, the Graffschaft Homburg, and the dominion Gimborn-Neustadt, the Graffschaft Mark, the former donors Essen and Werden, the Graffschaft Limburg and the city of Dortmund; of the Ruhr Department and the former Austrian Duchy of Limburg, now part of the Durte and Niedermaas departments. Forstmann et al., Aachen et al. 1804, digitized .

- Ruth Schmidt-de Bruyn: Culture and history in the Bergisches Land. From the past to the present. Bachem, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-7616-0809-8 .

- Bernhard Schönneshöfer: The history of the Bergisches Land. 2nd, increased and revised edition. Martini & Grüttefien, Elberfeld 1908.

- Daniel Schürmann : Kleine Bergische Vaterlandskunde: a New Year's present for school children and intended for future use in schools . Elberfeld, 1799. ( digitized version )

- Ulrike Tornow: The administration of the Jülich-Bergische land taxes during the reign of Count Palatine Wolfgang Wilhelm (1609-1653). Bonn 1974 (Bonn, University, dissertation, 1974).

Web links

- Internet presence of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein: bgv-habenverein.de

- Map of the Duchy of Berg in 1789

- Timeline of the history of the mountains ( memento from January 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- Sources and texts on Jülich, Kleve, Berg / Ghzgtm. (1475-1815)

- Grand Duchy of Berg at the Rheinische Geschichte portal, accessed on July 28, 2019

- Digitized version of a map: Carte Des Duchy of Berg . ( Digitized version )

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b T. R. Kraus: The emergence of the sovereignty of the Counts of Berg up to the year 1225 , p. 16.

- ↑ F. Greeting: History of the Bergisches Land , p. 66.

- ↑ Peter van der Krogt: Earth globes, wall maps, atlases - Gerhard Mercator maps the earth. In: Gerhard Mercator, Europe and the World. Duisburg 1994, pp. 81-130

- ↑ Map excerpt from Uwe Schwarz: Cologne and its surroundings in old maps. From the Eifel map to the general staff map (1550 to 1897). Published by Werner Schäfke. Cologne: Emons Verlag 2005, pp. 44–45, map 12, ISBN 3-89705-343-8 .

- ↑ Lacomblet, Theodor Joseph, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cologne, Certificate No. 329 , 1846, Volume 2, p. [209] 171. Digitized edition ULB Bonn

- ↑ For the power constellation before the battle of Worringen see: Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas zur Geschichte des Niederrheins . Cartography by Harald Krähe. Bottrop / Essen: Verlag Peter Pomp, 1999 (series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy, vol. 4), p. 32f

- ↑ Axel Kolozdziej: Duke Wilhelm I. von Berg (1380-1408) . In: Bergische Research. Sources and research on Bergisch history, art and literature . Volume XXIX. VDS-Verlagsdruckerei Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 2005, ISBN 3-87707-639-4 , p. 15

- ↑ Rolf-Achim Mostert: The Jülich-Klevian Regimental and Succession Dispute - a Prelude to the Thirty Years War? In: Stefan Ehrenpreis (Ed.): The Thirty Years War in the Duchy of Berg and in its neighboring regions . Neustadt an der Aisch: Verlagsdruckerei Schmidt, 2002, pp. 26–64 (Bergische Forschungen. Sources and researches on Bergische history, art and literature. Vol. 28)

- ↑ Klas E. Everwyn: "Soon the Russians will be here" ( Die Zeit 6/1990)

- ^ Kurt Kluxen : History of Bensberg. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 1976, ISBN 3-506-74590-5 , p. 68 ff.

- ↑ a b Digitized edition of the ULB Düsseldorf , p. 79.

- ↑ a b Rolf Müller: Upladhin - Opladen - Stadtchronik , self-published by the city of Opladen, 1974, p. 121 ff

- ↑ Michael Gutbier, The main regional and knight court in Opladen - investigations into the legal history of the county of Berg in the later Middle Ages, Leverkusen: Leweke, 1995

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, Document 665 , 1840, Part 2, 1201-1300, p. [429] 391. Online edition 2009

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Archive for the history of the Lower Rhine, Volume IV , p. 147 online

- ^ Axel Kolodziej , Duke Wilhelm I von Berg (1380–1408), p. 197

Remarks

- ↑ In the literature, even in the latest publications, the Keldachgau is often mentioned as part of the old settlements of the Bergisches Land (e.g. in Wilhelm Janssen : Das Bergisches Land im Mittelalter , in: Stefan Gorißen, Horst Sassin, Kurt Wesoly (ed .): History of the Bergisches Land. Until the end of the old duchy in 1806 , Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld 2016, p. 34.). However, this is based on the scientifically outdated location of the Keldachgau on the right bank of the Rhine.

Coordinates: 51 ° 12 ′ 26 " N , 6 ° 48 ′ 45" E