Altenberg Abbey

| Altenberg Cistercian Abbey | |

|---|---|

Altenberg Monastery |

|

| location |

Germany North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Coordinates: | 51 ° 3 '17 " N , 7 ° 7' 58" E |

| Serial number according to Janauschek |

70 |

| founding year | 1133 |

| Year of dissolution / annulment |

1803 |

| Mother monastery | Morimond Monastery |

|

Daughter monasteries |

Mariental Monastery (1143) |

The Abbey Altenberg ( Latin Vetus Mons , Abbatia Veteris Montis , bergensis Abbatia u. Ä.) Is a former monastery of Cistercian in the district of Altenberg the municipality Odenthal in Bergisch Land . It lies in the valley of the Dhünn . The monastery was founded in 1133 and secularized in 1803 . The monastery church, the Altenberg Cathedral, has been preserved to this day . Since the reconstruction of the ruins in 1847 by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The church has been used simultaneously as a Protestant and Catholic parish church .

history

Foundation, church and monastery building (12th - 17th centuries)

The monastery was founded as a filiation (offshoot) of the Morimond monastery in Burgundy . On August 25, 1133, twelve monks came from there under Abbot Berno to the Dhünntal. Initially, they had the ancestral seat of the Counts of Berg , the 11th century castle Berge on a rocky promontory on the slope of the Bülsberg above the Dhünn . Count Adolf II von Berg had given it to the Cistercians when he built a new castle with Schloss Burg an der Wupper. Adolf's older brother, Count Everhard von Berg , had entered the Cistercian monastery of Morimond in 1129. Another brother, Bruno II , was Archbishop of Cologne at the time . The three brothers donated the abbey out of thanks to God and at the same time created an appropriate family burial place with this “family monastery”.

The monks partially demolished the castle and rebuilt it. However, they soon moved their headquarters in the valley directly to the Dhünn, because this offered better conditions for the Cistercian way of life and the construction of a monastery according to the Cistercian ideal plan . There they began to build a large monastery and planted fields, a grain mill and fish ponds so that the abbey could take care of itself; the monastery rule did not allow healthy monks to meat from four-legged animals.

A first church, a three-nave Romanesque pillar basilica was (choir) and 1160 (long house) already in 1145 consecrated . Like all Cistercian churches, it was consecrated to Mary , the Mother of God . The monastery immunity reached up to the Dhünn. Along the Dhünn there were farm and mill buildings and, over time, four chapels next to the monastery church : the Marienkapelle directly in front of the monastery gate on the right (under Abbot Bruno, around 1250), the chapel of Saints Felix and Adauctus near the hospital (end of the 13th century ) and the abbot's chapel in the “Old Prelature” (consecrated on May 6, 1507). The oldest chapel on the monastery grounds, the St. Mark's Chapel on the Dhünn, built around 1225, has been preserved to this day. The northern section of the enclosure wall was restored at the end of the 20th century.

Adolf's brother, Archbishop Bruno II of Cologne, presented the monastery with lands that extended to the left bank of the Rhine. This laid a foundation for the abbey's growing wealth. The abbey enjoyed the protection of the German kings and several territorial rulers and was exempt from tithing for its own businesses ; it came under neither the jurisdiction of the bishop nor the secular jurisdiction. In the first decades after its founding, the abbey recorded so many admissions that it had to establish daughter monasteries. Those who entered increased the wealth of the abbey with the dowry they brought with them. At the end of the 12th century, 107 priest monks and 138 lay monks ( converses ) belonged to the abbey . For previous five start-ups were out of the Abbey ( Kloster Mariental , Monastery Łekno , Monastery Lond / Ląd , Kloster Zinna and monastery Haina ).

The earliest name of the abbey was cenobium, quod dicitur Berghe ("monastic community, called Berghe", 1138), the monastery was also called monasterium s. Marie de (in) Berg (h) e ("Monastery of St. Mary of (in) Berghe", 1148), monasterium Bergense (1180), the church ecclesia (see Marie) de Monte ("Church of St. Mary of / vom Berg “, 1150/65) or Bergensis (around 1180). The name "Altenberg" was first mentioned in 1195 in contrast to "Neuenberg", the castle on the Wupper.

In 1259, the foundation stone for a new, larger church, the high-Gothic Altenberg Cathedral , was laid on the site of the previous building, the choir and southern transept were consecrated in 1276. The final consecration of the entire building took place on July 3, 1379. According to the building regulations of the Cistercians, the cathedral has only one roof turret and no towers. He bears the patronage of St. Mary of the Assumption . At the same time as the cathedral was built, the monastery buildings were also expanded. Nothing is known about the motifs for the new building a hundred years after the first church was built. Hans Mosler speculatively mentions possible reasons for damage caused by an earthquake on January 11, 1222 and a “deliberate departure from the previous architectural tradition”, since the Altenberg abbots got to know the new Gothic architectural style on their trips to other abbeys in Western Europe. The Markuskapelle was built in 1225 in the Rhenish transition style between Romanesque and Gothic.

The location and construction of the monastery complex in the valley and on the water were also based on the Cistercian ideal plan, which goes back to Bernhard von Clairvaux . The immunity area of the monastery was bounded in the west by the Dhünn, over which a bridge led to the church; Various farm buildings for agriculture and fish farming were located along the Dhünn. To the east, the monastery district was enclosed by a wall in an approximately semicircular shape, the church and monastery were in the middle of this area. The monastery buildings formed a square to the south of the east- facing cathedral around an inner courtyard with a garden, and the northern wing was directly connected to the church building. The monastery and utility rooms and the church could be reached from the cloister around the inner courtyard. The rooms for the priest monks and the lay monks (conversations) were separated from each other. Both groups had their own refectories , dormitories and at times even separate infirmaries (hospital wards). The people of conversation entered the church via a "conversation passage" parallel to the western wing of the cloister, from where they reached the rear part of the church intended for them, the "conversation choir".

The first monastery buildings were simple and based on the Gothic . The cloister was built on the first, Romanesque church between 1222 and 1260; its north wing and the south aisle of the church shared a roof. The east wing of the cloister was two stories; on the ground floor by the church was the sacristy , south of it the chapter house with a size of 15 mx 15 m, divided by four bundled columns, as well as the kitchen and the dining room of the monks. The three-aisled dormitory was on the upper floor; it had a ribbed vault supported by 22 ornate columns. From there, the southern transept of the church was directly accessible to the monks via a staircase. The abbey's treasury was located above the sacristy and was only accessible from the dormitory. When the second, Gothic cathedral was built from 1259, these buildings were taken into account; this gave the cathedral a stunted south transept. The cloister opened up to the inner courtyard in ogival triplet arcades with inserted double columns. There were always expansions and modifications. Under Abbot Johannes Rente (1430-1440) the large, hall-like dormitory of the monks was divided into individual cells .

Under Abbot Johann Jakob Lohe (1686–1707) the abbey was repaired, significantly expanded and furnished with baroque style elements. To the west, the abbey building was enlarged by a second quadrum, on which the rooms of the conversations were also located. A copper engraving from 1707 by Johann Sartor shows this state of construction. The western entrance gate to the monastery grounds on the Dhünnbrücke and the buildings of the kitchen courtyard on the Dhünn near the St. Mark's Chapel, which have been preserved to this day and are entered through a baroque archway, also date from this time; This square courtyard with dairy, inn, stables and coach house served as a farm yard for the immediate supply of the abbey and had predecessor buildings from the time the monastery was founded. The orangery , a greenhouse south of the abbey with a glass south facade, was built towards the end of the 18th century. The monks cultivated citrus fruits there. Since such luxury fruits were usually not part of the cultivation program of a Cistercian abbey, this was possibly done on behalf of the Dukes of Berg.

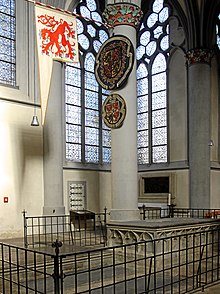

Altenberg as a resting place and burial place (12th - 18th centuries)

The founder, Count Adolf II, entered the Altenberg monastery himself after 1160, died there a little later and was buried in Altenberg, establishing the tradition of burials in Altenberg Cathedral for the Bergisch ruling house until the 16th century. Also Adolf's son, the Cologne Archbishop Bruno III. , was a monk in Altenberg after his resignation in 1193 and was buried there around 1200. The last was Duke Wilhelm III. ; on the occasion of his funeral on November 3, 1511, Emperor Maximilian I was a guest in Altenberg. Only two of the Counts and Dukes of Berg were not buried in the monastery church until the Jülich-Bergisch house was extinguished (1521).

The abbots' tombs have also been preserved in the cathedral from the 17th and 18th centuries. Before that, the abbots had been buried in the chapter house ; However, since Abbot Melchior von Mondorf was the first to receive the pontificals in 1637 , the abbots were buried in the church.

Other high-ranking personalities spent their twilight years in the abbey: Johannes von Sieberg (Syberg), auxiliary bishop in Cologne and Mainz , titular bishop of Skopje († 1366 or 1383) and Kuno , titular bishop of Megara and auxiliary bishop of Lüttich († 1366); Daniel von Wichtrich , 1342 by Pope Benedict XII. appointed bishop of Verden , retired to Altenberg in 1356 after disputes with his cathedral chapter and died there. A great benefactor of the abbey was Bishop Wikbold Dobilstein (Dobbelstein) von Kulm , who resigned as bishop in 1385 after disputes in his diocese and came to the Altenberger Hof in Cologne. Although he did not become a monk of the abbey, he generously supported it for decades. Thanks to his foundations, the Altenberg Cathedral was completed, which Bishop Wikbold himself consecrated in 1379 and where he was buried in 1398.

Development up to secularization (13th-18th centuries)

Due to its favorable location on the Dhünn River, the abbey was an important part of the region's economy. It was also promoted by the rulers of the Duchy of Berg and the Archbishops of Cologne, for example through exemption from taxes.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the abbey owned twelve farms ( grangia or curtes ) outside of its location on the Dhünn , including several wineries: in Lützelfeld am Main, the Petersackerhof in Rheindiebach near Bacharach , the Kapellenhof near Rhens , Horchheim , Sürth , Forsterhof, ( District of Bergheim (Erft) ), Bochheim near Kerpen- Manheim , Schönrath , Isenkroidt in Titz , Widdauen near Reusrath , Brück and Mickel near Düsseldorf .

Towards the end of the 12th century, the monks in Cologne founded the "Altenberger Hof" ( curia ecclesie de veteri-monte on the Niederich in the area of today's Johannisstrasse near the main station, known as "the Aldeberg") as a widely important trading center Organizational center for the economy of the monastery; Until the 15th century, it also served the Bergisch rulers as a residence and place of negotiation, as well as the Altenberg abbots, some of whom stayed in Cologne more than in Altenberg in the 18th century; the court now had a lordly format. On July 8, 1481, Duke Wilhelm's wedding ceremony with Sibylla von Brandenburg took place there; Abbot Arnold performed the wedding . The abbey acquired another Fronhof in what is now Cologne-Nippes in 1432; In 1549 a bakery was built there, in 1749 the courtyard buildings were partially rebuilt under Abbot Johannes Hoerdt, of which a coat of arms stone with the coat of arms of Abbot Johannes still testifies today. The buildings of this Altenberger Hof now serve as a community center.

In the course of its history, the abbey had properties in over 160 places, mainly in the Duchy of Berg (78 places), in Cologne (city and archbishopric , 42 places), in the Duchy of Jülich (22 places), on the Middle Rhine (17 places) Free float as far as Westphalia and the Main (10 locations). The greatest expansion of the property was recorded around the beginning of the 16th century, but since the 15th century almost all of the property had been leased. At the end of the 18th century, before the expropriation by the French and secularization, the abbey still had properties in around 130 locations.

Solingen was affected by the Reformation , where the Altenberg Cistercians were active in pastoral care; Abbot Wilhelm Stoploch intervened unsuccessfully around 1560 against the transition of the local parish church to Protestantism . Altenberg lost its daughter monasteries Mariental, Zinna and Haina . The Cologne area, however, remained with Catholicism , and this position was consolidated by Duke Wolfgang Wilhelm's conversion to Catholicism in 1613. In Lower Saxony ( Derneburg , Wöltingerode ) and in the Magdeburg area, the abbey was successful in the Counter-Reformation , albeit with no long-term effect .

Some of the abbey properties suffered from the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War , several monks were taken prisoner; the Altenberg site itself was not affected. After a phase of spiritual and economic stagnation from the 15th century, a period of prosperity began around the middle of the 17th century, a "time of undisturbed reconstruction and increasing prosperity" lasting over 100 years. Altenberg achieved a leading position in the Low German Cistercian province. At the end of the 17th century, the buildings were repaired and several conversions and new constructions were carried out, such as the aforementioned western part of the abbey, the baroque kitchen courtyard, the entrance gate opposite the western facade of the cathedral at the transition over the Dhünn and later the orangery. During this time, the abbey comprised between 30 and 40 conventuals who were entitled to elect an abbot, as well as novices and conversations .

Abbot Franz Kramer (1779–1796) then led such a dissolute life at the expense of the abbey that he had to abdicate after the convent rebelled against him. He lived mainly in the Altenberger Hof in Cologne, where he had seventeen horses, seven carriages and his own servants, while he did not take care of the monks and the finances of the abbey. His successor and last abbot of Altenberg, Joseph Greef (1796–1803), was personally modest, but not the conflicts in the abbey and the challenges of economic management as a result of the over-exploitation of his predecessor and the French occupation of the left bank of the Rhine at the end of the 18th century grown. The French had imposed a war contribution on the Duchy of Berg , which was passed on by the government in Düsseldorf; because an incorrect calculation key was used as a basis, the abbey accounted for more than a third of what the entire Bergisch clergy had to pay, without the abbot objecting to it.

Altenberg monks

The number of monks ( fratres monachi , sacerdotes , also domini "lords") and conversations ( fratres conversi , laici ) was initially several hundred. After the filiations and because of the conversion of monastic agriculture to leasing, the number of priest monks from the 16th century was usually between 30 and 40. The superiors and officials were usually priest monks, but the monastery property could also be managed by a conversant . From the 16th century onwards , donati were also affiliated to the abbey , who lived without vows and sometimes married with their families in the vicinity, worked for the abbey and were maintained by it. The majority of the 900 monks who can be identified by name are likely to come from Cologne and the Rhineland to the Lower Rhine, as Mosler deduces from an analysis of the 480 monks known by surname; of the 20 abbots since 1520, 16 came from Cologne. They came from all classes of the bourgeoisie, from patrician families to the petty bourgeoisie. At least 80 of the Altenberg monks were of peasant origin and many of them came from tenant families and from areas in which the abbey owned lands, but their share has recently declined sharply; Mosler speaks of an “urbanization of the convent” for the 18th century. The initially higher proportion of nobles in the convent had also fallen sharply.

A sign of the abandonment of the Altenberg Abbey from the original ideal of “pray and work” of the monks is that in the 18th century even novices paid tips for numerous tasks to employees of the monastery who were at their service. The abbots had valets and coachmen. Not only on the estates, but also in the abbey itself, employees worked as shoemakers, tailors, locksmiths, joiners, bakers and gardeners. From the 12th to the 16th century, the abbey had a weaving mill - the “Weffhuys” - with a magister textrini as director.

None of the Altenberg monks was canonized. Blessed Gezelinus von Schlebusch , who is said to have lived as a shepherd on the Altenberger Hof in Alkenrath , is said to have been a converse of the abbey, but there is no evidence there.

Also as a bishop , eminent scientist or theologian, no member of the abbey emerged. In 1426 the first monk went to Heidelberg to study from Altenberg to the Cistercian preparatory college St. Jakob, founded there in 1387, and eight more followed in the 15th century. Altenberg monks also studied at the University of Cologne or entered the abbey after completing their studies there. Abbot Arnold von Monnickendam (1467–1490) was a professor in Heidelberg , Abbot Johannes Blanckenberg (1643–1662) served twice as rector of Cologne University. For all young priest monks there was home study in the abbey, the older ones were responsible for self-study. The abbey library was adequately equipped for this. The one-year training of the novices before their final admission to the abbey had a spiritual and liturgical focus, it was intended to familiarize them with the Cistercian way of life and life in the monastery.

Life in the monastery

Monastery life was determined by the divine service, the officium divinum , consisting of choir prayer and the celebration of Holy Mass . The monks were active as pastors in the dependent parishes and convents, as well as in the management, administration and management of the branched lands and properties of the abbey, insofar as these were not leased. They also helped out in other monasteries, including Worms and Magdeburg , where they took on functions such as prior office (Peter Kurtenbach around 1630 in Bottenbroich , Anton Eck in the Cistercian monastery in Wöltingerode ) or the novice master (Johann Unverdorben around 1626 in the Mariawald Abbey ). From 1663 Johann Nigelgen was abbot at Marienrode Abbey near Hildesheim. About a third of the conventuals were permanently absent from Altenberg for such reasons.

Altenberg Abbey had an infirmaria , a sick department under the direction of the infirmar , initially separate for monks and conversations. In 1494/95 a new building with its own bathing room was built for this purpose, and again in 1775.

Up until the time of printing in the 16th century, there was a scriptorium in the abbey , a writing room in which numerous scribe monks created and enlarged the library by copying. The first monks brought a foundation with them from Morimund when it was founded; Then it was necessary to enlarge and maintain the stock in Altenberg, but also to provide the filiations with an initial set of books. The surviving manuscripts are evidence of the great care taken in writing and of remarkable artistic quality. The library mainly comprised theological literature: Bibles , the writings of the Church Fathers and theologians, sermon literature, but also Roman literature and books of historical and geographical-ethnological content. After the scriptorium was closed, the library was supplemented by printed works. After secularization, the library was transferred to the relevant departments of the electoral library in Düsseldorf; for the transport from Altenberg on November 25 and December 6, 1803, 29 crates and two large barrels were required, which were brought to Düsseldorf on fifteen carts drawn by two or three horses. With the electoral library, the Altenberg works later came to the Düsseldorf state and city library.

Abbots

The abbey was headed by 57 abbots in the course of its history. Many of them took on overarching management tasks of the order in Germany and were commissioned with visitations in other abbeys and monasteries.

The abbot was elected for life by the professions of the abbey if he did not abdicate or was deposed. The election was led by the “father abbot” (the abbot of Morimond ) or a deputy appointed by him. In the 16th century, an election by the highest functionaries of the abbey and a limited number of "electors" co-opted by them was common - which led to increasing dissatisfaction in the convent - and in the 17th century it was also once only the priests elected the professed . The election officer had a certain leeway with these regulations. After the election, the elected person took a solemn oath to perform his official duties carefully for the good of the abbey and was ordained abbot. In Altenberg this was always done by the Archbishop of Cologne because of the traditionally close proximity of the abbey to the archbishopric . With a few exceptions (Giselher, 1250–1264 and Arnold von Monnickendam, 1467–1490), an Altenberg monk was always elected abbot, usually one of the older monks who had previously held a leadership position in the abbey.

The abbot had certain privileges of honor. He had his own cash register and special income for which he was not accountable, and represented the abbey externally; so he had to attend the general chapter of the Cistercian order personally and was father abbot of the daughter monasteries of Altenberg. Most recently, the Altenberg abbots had the right to sit in the Cologne state parliament as "Lords of Riehl, Dirmerzheim and Glesch".

Inside, the abbot was in charge of auctoritate paterna , “with paternal authority”, and performed certain sacred acts. He accepted novices and filled the parish posts under the monastery patronage. From 1648 the Altenberg abbots wore the pontificals such as staff, miter and pectoral cross and thus had the rank of bishop. Since the 16th century, numerous abbots did not live in Altenberg, but mainly resided in the Altenberger Hof in Cologne.

The abbots carried a seal , which was initially also the seal of the convent, until it had its own seal after 1335 by papal instruction. The Altenberg convent seal shows the Virgin Mary standing with the baby Jesus in her arms, to whom she is handing an apple. The abbot's seal depicts an abbot in a pose that has become more and more elaborate over the centuries.

The abbey had had a coat of arms since the late 15th century . On a red or gold background it shows a golden abbot's staff growing out of a green three-mountain - an allusion to the location, name and origin of the abbey.

Offices in the monastery

The following functions and offices existed in the monastery management and administration in Altenberg from the beginning, which formed the circle of seniores (around 1500 also called officiales ):

- The prior supervised the convent and ensured that the rules of the order were observed.

- The Bursarius (Bursar), Cellerarius or Kell (n) he was responsible for the economic management of the abbey and probably also its farms outside ( grangia ). The master of the Altenberger Hof in Cologne, the procurator curiae Coloniensis , initially served alongside and later in place of the bursary. Lord of the kitchen in Altenberg was later the praefectus novae curiae .

- Cantor

- Hospitalarius (head of the monastery hostel), later replaced by the dispensator (Almosenausgeber), also spindarius called

- Vinarius (wine master), coquinarius or culinarius ( kitchen master ) and refectorarius (the caterer of the dining room )

- Custos and / or sacrista ( sacristan )

- Infirmarius or infirmary master

- Portarius or porter

- Lector

- Magister novitiorum ( novice master )

At times the main functionaries had deputies ( subbursarius , subcellerarius ), the prior almost always had a subprior to support him. Until around 1550, prior, waiter, infirmary, guest master, sacristan and porter had special funds, which were added to the convent fund from the 16th century.

The abbot was the pastor of the monks. The secular employees of the abbey and their families were subordinate to the pastor of St. Pankratius in Odenthal . In the event that the pastor was difficult to reach, the abbey had had the privilege of Pope Gregory IX since 1236 . that a monk was allowed to administer the sacraments to the rear passengers . Like numerous families from the Altenberg area, they took part in the public service in the monastery church. Around 1800 there should have been 1000 believers regularly. In the 18th century, a monk of the monastery is referred to as a pastor familiae , who was entrusted with the spiritual care of the servants.

The abbey in the Cistercian monastery family

According to the rules of the Cistercian Carta Caritatis, Altenberg belonged to the line of Morimond Abbey. The abbot of this abbey was pater direktus , the immediate superior with the right to visit ; according to his ius adhortandi, corrigendi, reformandi, puniendi he had to admonish, correct, reform and punish. A close relationship ( fraterna familiaritas et caritativa communitas ) existed with the Kamp Abbey , whose affiliation ten years before Altenberg had also taken place from Morimond. The abbots represented one another, and in emergencies and conflicts one helped one another out. From the 15th to the 17th century the abbots of Altenberg were repeatedly order commissioners and vicars general of the Lower German order province. Mosler sees the duration and frequency of these tasks as "proof of the reputation Altenberg enjoyed in the order at that time" - possibly also because of the abbey's extensive possessions.

Filiations

In the first century of its existence, Altenberg Abbey had five subsidiaries: Mariental Abbey (near Helmstedt ), Łekno Abbey and Lond / Ląd Abbey ( Greater Poland ), Zinna Abbey ( Mark Brandenburg ) and Haina Abbey ( Kellerwald ). Hude ( Oldenburg ) Monastery was founded by Mariental in 1232 , and Obra Monastery in 1237 from Łekno , also in Greater Poland.

When the Mariental Abbey was abolished in 1569 as a result of the Reformation , some Mariental monks sought refuge in Altenberg, as did the monks from Haina. In Haina, an abbot (Hermann von Köln) was elected again in 1558, but he could not find a successor because there was no longer a convent. In 1648 the Cistercian Abbot General carried out the formal “union” of the Haina and Altenberg abbeys, whereby the right of the Haina abbots to carry the pontificals passed to the Altenberg abbots.

There was a lively connection to the daughter monasteries Łekno and Lond in the east as well as to the "grandchildren" monastery in Obra. The abbeys were called "Cologne monasteries" because they were occupied by conventuals of Rhenish origin, and were bases of the eastern colonization ; farmers from the Rhineland also settled there around the abbeys. In the 15th century, after the influence of the Teutonic Order ended , the country became Polish and the abbeys were subordinated to the Abbot of Paradyż by the General Chapter of the Cistercians . The relationship with the Zinna monastery ended early.

In 1651 the former Cistercian monastery of Derneburg ( Diocese of Hildesheim ) was converted into a Cistercian monastery and initially placed under the Altenberg paternity, when it became Catholic again after the Reformation with the "Great Hildesheim Monastery". Bishop Ferdinand was at the same time Bishop of Hildesheim and Archbishop of Cologne. However, the formal assignment relationship was not confirmed by the General Chapter in 1699, a desired affiliation relationship with the Marienrode Abbey never came about. Nevertheless, there were still friendly relations between Altenberg, Derneburg and Marienrode.

Incorporated women's monasteries

The Altenberg Abbey had supervisory and pastoral functions in several Cistercian monasteries that were not founded in Altenberg, but with which there were close relationships ( filiae immediatae , immediate daughters). For canonical and theological reasons, these functions were reserved for priests and could not be performed by a local conventual. Altenberger abbots led the election of the superiors, took pictures and dressed new nuns as well as the church supervisory visitations , provided confessors and pastors. The prior or provost represented the nuns' abbey to the outside world, vis-à-vis the respective diocese and the sovereign rulers, and concluded contracts for the abbey, usually in agreement with the abbess .

There were

- as the oldest the Cistercian abbey Benden , also "Marien-Benden", near Brühl (patronage attested from 1269 to 1803),

- in Cologne the Mechtern Abbey ( monasterium ad Martyres ), settled with Cistercian women in 1277, moved to St. Apern in 1474 and abolished in 1802,

- Kentrup / Kentrop near Hamm (assigned to Altenberg in 1277, repealed in 1808),

- Marienborn Abbey in Hoven (from the beginning of the 16th century filia immediata von Altenberg - previously von Heisterbach -, abolished in 1802),

- Wöltingerode (since about 1180 Cistercian convent, temporarily Lutheran in the 16th / 17th centuries , again occupied by Cistercian women after 1643, who in 1650 after a visit from Abbot Blanckenberg asked to be incorporated into the Altenberg monastery family, canceled in 1802) and

- St. Georgenbusch / St. Jöris (founded before 1300, the jurisdiction came to the Abbot of Clairvaux in the 18th century after rivalries between the Abbeys of Heisterbach and Marienstatt , who commissioned the Abbot of Altenberg with the supervision and renovation in 1759, abolished in 1802).

Altenberg monks also worked as confessors in other nunneries, primarily in the Rhineland, but also in several monasteries in the Magdeburg area.

Abolition of the abbey

In 1803 the monastery was secularized as a result of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss . On September 12, 1803, Elector Maximilian decreed that all monasteries, abbeys and monasteries in the Duchy of Berg were also abolished, with the exception of the monasteries that were dedicated to nursing the sick. The 22 monks of Altenberg Abbey were given a pension by the state and left the abbey on November 30, 1803, Abbot Joseph followed on December 1. In 1804 the inventory was auctioned and the Altenberger Hof in Cologne sold in favor of the French tax authorities.

Most of the monks (13) went to parish pastoral care, they became primissar , vicar or pastor in a parish in the area ( Bechen , Burscheid , Opladen , Lützenkirchen , Hitdorf , Flittard or Cologne ), some also in more distant places such as Itter , Soller or Trier . It is not known whether several of them continued to serve as clergymen; they may have returned to their families. Eight monks died by 1815, seven more by 1830. Probably only one of the monks, P. Palmatius Boltz, visited the Augustinian monastery Rösrath , which on the part of the state remained as a central and extinction monastery for the abolished monasteries in the area; the year of his death is unknown. Late at the age of 80, P. Gaudentius Courtin died on March 3, 1845 as rector "at All Saints" in Cologne. The last of the Altenberg monks, Father Konstantin Habrich, initially stayed in Altenberg, where he continued to hold services for the population in the abbey church and at the same time worked for the buyer of the abbey buildings as an economist and landlord. After the fire in the cathedral in 1816 he went to Schlebusch as Primissar , where he died on November 2, 1847 at the age of 81.

Continued use of the building systems

19th century

In 1806, the church and monastery complex in Altenberg was sold by the interim owner, the Bavarian King Maximilian Joseph , to the Cologne wine merchant Johann Heinrich Pelpissen for 26,415 Reichstaler. The chemists Johann Gottfried Wöllner and Friedrich Mannes leased the site and set up a chemical factory there to produce Berlin blue . After an explosion and subsequent fire in the night of November 6th to 7th, 1815, the monastery buildings and the roof of the abbey church were destroyed. The monastery buildings and the church fell into disrepair. In 1830 considerable parts of the south transept, the crossing and the adjoining choir sections of the cathedral collapsed. In the following years the owners changed several times. The facility was eventually used partially as a quarry.

From 1834 the first security measures were taken on the church building. After the church ruin was donated to the Prussian state, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III supported. significantly the restoration of the abbey church with the condition that it will be used as a simultaneous church in the future . The first Protestant service took place on August 13, 1857. In 1863, the Archdiocese of Cologne built a parsonage, the "Archbishop's Villa", south of the cathedral for the Catholic community .

Altenberg House

From 1922, the area of the former abbey was leased by the Catholic Young Men’s Association and, together with the cathedral, became a center for church youth work. The buildings, which were largely newly constructed in various construction phases between 1922 and 1933, were modeled on the earlier abbey buildings in terms of their layout and shape. They are called Haus Altenberg . From 1926 to 1954 it was the center of the Catholic youth movement in Germany, with interruptions caused by the war . The Altenberg house, which has been sponsored by the Archdiocese of Cologne since 1954, now also manages the “old brewery” on the Dhünn and the orangery, which houses conference rooms and an official apartment; For a few years it also used a wing of the kitchen courtyard, which it called "House Morimond". In the 1970s and 1980s, Rector Winfried Pilz took up the monastic tradition of Ora et labora ( pray and work ) for youth work and invited to Ora-et-labora weeks at Haus Altenberg. In this context, the “Action Group Altenberg eV - Forum for the Maintenance of Cistercian Tradition” was established in 1983, which leased the kitchen yard and ran a restaurant, event rooms, a pottery, a lapidarium and a herb and farm garden. In 2018 the leasehold contract expired; the owner Hubertus Prinz zu Sayn-Wittgenstein wants to use the building primarily for gastronomy after a renovation.

In January 2013, a thorough renovation of Haus Altenberg began by the Archdiocese of Cologne in close coordination with the preservation authorities. The facades were retained, but the historic gate from 1933 has been reopened and is the new main entrance. The structure now makes the original structure of the abbey more recognizable. In the course of the renovation, extensive archaeological excavations and building research projects were carried out on the abbey grounds. Haus Altenberg was reopened on August 14, 2016 and blessed by Cardinal Rainer Maria Woelki . The Archdiocese of Cologne invested 41 million euros in the renovation as the client.

The Edith Stein retreat house of the Archdiocese of Cologne was housed in the old brewery from 2014 to 2018, while the former Benedictine abbey in Siegburg was rebuilt. After completion, the retreat house is using the premises in the former Siegburg Abbey together with the Catholic Social Institute.

See also

swell

- Extract of the general inventory of the furniture assets of Altenberg Abbey. Altenberg, Düsseldorf 1819. Digitized

- Hans Mosler: Document book of the Abbey Altenberg. 2 volumes (vol. 1: 1138–1400 , vol. 2: 1400–1803 ) (= document books of the spiritual foundations of the Lower Rhine. 3, 1–2). Hanstein et al. a., Bonn u. a. 1912-1955.

literature

- Aegidius Müller: Contributions to the history of the Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Bensberg 1882. Digitized

- R [obert] Keller: Altenberg and his oddities. Haake, Bensberg 1882. Digitized

- Paul Redlich: The last days of Altenberg Abbey. In: Annals of the Historical Association for the Lower Rhine . 72, 1901, ISSN 0341-289X , pp. 102-141 ( online ).

- Helene Ermert: The rural property of Altenberg Abbey until the end of the 15th century. Dissertation, Bonn 1924.

- Hans Mosler: The dioceses of the church province of Cologne. The Archdiocese of Cologne 1. The Cistercian Abbey of Altenberg. Germania Sacra ; New episode 2. Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin 1965. (digitized version)

- Landscape and History e. V. (Ed.): Looking for traces in Altenberg. Landscape and history in the heart of the Bergisches Land. Gaasterland Verlag, o. O. 2006, ISBN 3-935873-06-9 (authors: Manfred Link, David Bosbach, Randolf Link).

- Nicolaus J. Breidenbach : The Altenberg Abbey - its goods and relationships with Wermelskirchen. In: Altenberger Blätter. No. 35, 2006, ZDB -ID 1458565-0 , pp. 5-87.

- The donation from the Steinhausen court. In: Nicolaus J. Breidenbach: The Altenberg Abbey - its goods and relationships with Wermelskirchen. In: Altenberger Blätter. No. 35, 2006, ZDB -ID 1458565-0 , p. 63f.

- Altenberger leaves. Contributions from the past and present of Altenberg. Issue 1 (November 1998) - Issue 61 (April 2015)

- Petra Janke: Baroque option. The Altenberg Cistercian Church in the late blooming phase of the monastery 1643-1779 . Berlin 2016.

Web links

- Holdings in the State Archive of North Rhine-Westphalia, Düsseldorf

- Altenberg in the CISTOPEDIA - Encyclopædia Cisterciensis

- Homepage of Haus Altenberg

- Hermann Josef Roth : Altenberg Cistercian Abbey in the Biographia Cisterciensis , October 2019

- Legends and stories

- The brothers from the mountains or the foundation of the monastery

- The re-establishment of the Altenberg monastery

- The roses at Altenberg

- The water devil near Altenberg

- The nightingales in Altenberg monastery

- The Ave-Marien-Ritter zu Altenberg

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 47.

- ^ Cistercium. The world of the Cistercians.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 15f.

- ^ History . Website of the Catholic parish of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt Altenberg. Retrieved November 16, 2012 .; Landscape and History e. V. (Ed.): Looking for traces in Altenberg. Landscape and history in the heart of the Bergisches Land. Gaasterland Verlag, o. O. 2006, ISBN 3-935873-06-9 , pp. 6-25.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 21f.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 15f.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 48f.79f.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 2.

- ↑ See: Sabine Lepsky: The former Cistercian abbey church Altenberg. Summary of the history of its origins. In: INSITU. Zeitschrift für Architekturgeschichte 6 (2/2014), pp. 149–168.

- ^ Landscape and History eV (ed.): Looking for traces in Altenberg. Landscape and history in the heart of the Bergisches Land. Gaasterland Verlag, o. O. 2006, ISBN 3-935873-06-9 , p. 7 (authors: Manfred Link, David Bosbach, Randolf Link).

- ^ Landscape and History eV (ed.): Looking for traces in Altenberg. Landscape and history in the heart of the Bergisches Land. Gaasterland Verlag, o. O. 2006, ISBN 3-935873-06-9 , p. 23ff. (Authors: Manfred Link, David Bosbach, Randolf Link).

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, p. 16 note 2 and p. 17.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 94.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 179.

- ^ Landscape and History eV (ed.): Looking for traces in Altenberg. Landscape and history in the heart of the Bergisches Land. Gaasterland Verlag, o. O. 2006, ISBN 3-935873-06-9 , p. 27f. (Authors: Manfred Link, David Bosbach, Randolf Link).

- ↑ odenthal-altenberg.de: Orangery.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 53.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 20.60.172.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, pp. 16f.33.89f.152.217.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 102f.

- ↑ Landscape and History e. V. (Ed.): Looking for traces in Altenberg. Landscape and history in the heart of the Bergisches Land. Gaasterland Verlag, o. O. 2006, ISBN 3-935873-06-9 , p. 38f.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 58.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 53.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, p. 103; Lists of places p. 103–120.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 53f.56.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 57.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 126.194-206.

- ^ Altenberger Domverein: History.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 184–188.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 126–129.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 126ff.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 89.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, pp. 98ff. 158-161.173ff.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 133.194-206.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 131.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, pp. 32-36.100f.

- ^ Montanus : The Altenberg monastery in Dhünthale and the monastic system. Friedrich Amberger, Solingen 1838, pp. 9–35 (lists all abbots)

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 69.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 133-137.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, pp. 130-133; for the official titles cf. JF Niermeyer, C. van de Kieft: Mediae latinitatis lexicon minus. 2 volumes, Scientific Book Society, 2nd edition, Darmstadt 2002.

- ↑ "The granarius , who only met in 1506 , obviously had the function of the waiter" writes Mosler (p. 131), which does not correspond to the usual names.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, p. 132 note 1.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 132.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 66ff.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 69.

- ^ Hermann-Josef Roth: Altenberg . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 1 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1993, Sp. 446 .

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 78–83.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 83-88.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 88.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, p. 59f.

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. Berlin 1965, p. 250; Mosler calls " Reusrath ", but what is meant is Rösrath .

- ^ Hans Mosler: The Cistercian Abbey Altenberg. (= Germania Sacra; New Series 2. ) Berlin 1965, pp. 250-253.

- ↑ Winfried Pilz, Peter Jansen: Ora et labora. Young Christians discover a program. Kösel-Verlag, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-466-36167-2 .

- ↑ aktionskreis-altenberg.de.

- ↑ Long lease expires. Action group Altenberg has to move out of the kitchen yard. In: Kölner Stadtanzeiger. October 2, 2018.

- ^ Church newspaper for the Archdiocese of Cologne, issue 42/12, October 19, 2012; Information brochure of the Archdiocese of Cologne ( Memento from December 24, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 5.8 MB)

- ↑ Bergisches Handelsblatt, August 16, 2016 ; domradio.de, August 15, 2016 , accessed on September 25, 2016.