Germany. A winterstory

Germany. A Winter's Tale (1844) is a satirical verse epic by the German poet Heinrich Heine (1797–1856). A trip that the author undertook in the winter of 1843 and that took him from Paris to Hamburg provides the framework for this.

The subtitle Ein Wintermärchen alludes to William Shakespeare 's romance of old age The Winter's Tale (1623) and suggests that Heine's cycle of poems is the counterpart to the verse epic Atta Troll, written three years earlier . A Midsummer Night's Dream understood that its subtitle also owes a work of Shakespeare: the comedy A Midsummer Night's Dream (1600). The formal relationship between the two epics is also shown by the fact that the winter fairy tale , like the Atta Troll , includes exactly 27 Capita , whose stanzas also consist of quatrains.

History of origin

Dissatisfied with the political conditions in Germany during the period of the Restoration , which, as a baptized Jew, did not offer him any legal work, and also to avoid censorship , Heine emigrated to France in 1831 .

In 1835 a resolution of the German Bundestag banned his writings together with the publications of the poets of Junge Deutschland . At the end of 1843 he returned to Germany for a few weeks to visit his mother and his publisher Julius Campe in Hamburg . On the return journey, the first draft for Germany was created, initially as an occasional poem . A winter fairy tale , which he developed into a highly humorous travel epic over the course of the next three months , into versed travel pictures that breathe a higher level of politics than the well-known political stinking rhymes. His publisher at the time, however, found the work too radical from the start and warned his protégé:

"You will have to suffer a lot for these poems [...] Not to think that you are giving the patriots new weapons against you and thus calling the French-eater in their place again, the moralists will attack you too [...] Truly." , I have never wavered as much with one of your articles as with this one, namely what I should or should not do. "

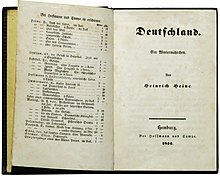

The finished verse epic was published by Hoffmann und Campe in Hamburg in 1844 . According to the twenty-sheet clause , a censorship guideline of the Carlsbad Conference of 1819, manuscripts of more than twenty sheets , i.e. more than 320 pages, were not subject to censorship before printing. Hence the publisher brought Germany. A winter fairy tale along with other poems in the volume Neue Gedichte . Nevertheless, to his regret, before the publication of his work, Heine had to undergo “the fatal business of reworking” and attach numerous “fig leaves” to the verses in order to prevent the foreseeable general “sniffing” and to defend himself against the accusation of being a “despiser of Fatherland ”and partisan“ friend of the French ”.

As early as October 4, 1844, the book was banned and confiscated in Prussia. On December 12, 1844, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia issued an arrest warrant for Heine. In the period that followed, the work was repeatedly banned by the censorship authorities . In other parts of Germany it was available in the form of a separate edition - also published by Hoffmann and Campe - but Heine had to shorten and rewrite it.

content

Overview

The following overview of the chapters shows the rough course and the main stations of the literary carriage ride: Capita I - II: French-German border; Chapter III: Aachen; Capita IV - VII: Cologne; Capita VIII - XIII: Westphalia (Mülheim, Hagen, Unna, Paderborn); Capita XIV - XVII: excursus on Emperor Barbarossa; Caput XVIII: Minden; Caput XIX: Bückeburg and Hanover; Capita XX - XXVI: Hamburg; Caput XXVII: epilogue.

The actual outward journey, which did not take place “in the sad month of November” ( Caput I , first verse), but in October and “which was extremely boring and tiring”, took the shorter route via Brussels, Münster, Osnabrück and Bremen to Hamburg . Only the return journey (from December 7th to 16th) passed through the stations indicated above.

Heine combines his travelogue on the basis of regional, historical and autobiographical facts with political and philosophical considerations. The first-person narrator puts his “illegal” thoughts in the foreground, which he, so to speak, hid as a “ contraband ” (smuggled goods), contrary to the prohibition, with him.

Germany. A winter fairy tale shows Heine's richly pictorial poetic language in close connection with sarcastic criticism of the conditions in his homeland. The author contrasts his liberal social vision with the gloomy “November image” of the reactionary homeland. Above all, he criticizes German militarism and reactionary chauvinism against the French, whose revolution he sees as the departure of a more social Europe. He admires Napoleon as the finisher of the revolution and the realizer of freedom. He does not see himself as an enemy of Germany, but as a patriotic critic out of love for the fatherland: Plant the black, red and gold flag at the height of German thought, make it the standard of free humanity, and I want to give my best heart and soul for it. Calm down, I love the fatherland as much as you do.

To the individual chapters

Caput I : After thirteen years in exile, H. is not without emotion, for the first time back at the German border and feels wonderfully strengthened as if by magic . In the face of a little harp girl who sings the old lyre of the earthly valley of tears with true feeling and a false voice , he promises his German friends (with the now following verse epic) a new song, a better song : We want to establish the kingdom of heaven here on earth .

Caput II : Before H., full of euphoria, with only shirts, trousers and handkerchiefs in his luggage , but a chirping bird's nest in his head / Of confiscated books , can enter German soil, his luggage is visited and sniffed by the Prussian customs officers : You fools, the You're looking in the suitcase! / You won't find anything here! / The contre gang that travels with me / I've got it in my head.

Caput III : In the boring nest of Aachen, H. meets Prussian soldiers again for the first time: Still the wooden pedantic people, / Still a right angle / In every movement, and in the face / The frozen conceit. H. blasphemed their mustaches ( the braid that once hung behind / it is now hanging under their noses ) and makes ironic fun of the helmet and the spiked hat : it was a royal idea! / The punch line is not missing, the point! / I'm only afraid if a thunderstorm arises / Pulls a bit like that / Down on your romantic head / Heaven's most modern lightning!

Caput IV : On the onward journey to Cologne , H. scoffs at the anachronistic German society, which prefers to turn backwards to complete the Cologne Cathedral , which has been unfinished since the Middle Ages , than to face the new era. The fact that work on the medieval building was stopped in the course of the Reformation meant real progress for the poet: the overcoming of traditional thinking and the end of intellectual immaturity. In the separate edition, H. replaced the last stanza from the Neue Gedichte edition with five new ones in which he criticized the Holy Alliance .

Caput V : H. meets the Rhine , as Father Rhine a German icon and a German place of remembrance. The river god, however, shows himself to be a dissatisfied old man, tired of the German chatter. He longs for the happy French, but fears their parody of Nikolaus Becker's politically compromising Rhine song , which portrays the river as a pure virgin who does not want to have her maiden wreath stolen. But H. can reassure him: The French have now become even worse Philistines than the Germans. They no longer sing, they no longer jump and now they drink beer and read Fichte and Kant .

Caput VI : H. expresses the conviction that thoughts once thought cannot be lost again and that revolutionary ideas will prevail in reality in the long run. As the executive organ of his revolutionary thoughts, H. lets a demon appear who, like a lictor, carries an ax in front of him and has followed him for a long time as a shadowy companion, always present and waiting for a sign to immediately carry out the poet's judgment: “Me am the act of your thought. "

Caput VII : Followed by his silent companion H. wanders through Cologne. At last he reaches the cathedral with its shrine to the three kings and smashes the poor skeletons of superstition . The three kings can be seen as an allusion to the reactionary holy alliance of the great powers Prussia, Austria and Russia. Germans are confidently alone in the “air realm of dreams” .

Caput VIII : H. drives the carriage over the postal route from Cologne to Hagen. The journey first leads through Mühlheim (now Cologne-Mülheim ), which in H. recalls his earlier enthusiasm for Napoléon Bonaparte . The reshaping of Europe had aroused hope in H. that freedom would be perfected.

Caput IX : In Hagen , H. enjoys the old Germanic cuisine with sauerkraut, chestnuts, kale, stockfish, kippers and sausages, seasoned with satirical tips against metaphorical pigs' heads - we still decorate pigs with laurel leaves - and an all too pious one Goose: She looked at me so meaningfully, / So deeply, so faithfully, so woe! / Certainly had a beautiful soul / But the flesh was very tough.

Caput X : H. sings a good-natured song of praise to the dear, good Westphalians : They fight well, they drink well, / And when they shake hands with you / For friendship, they cry; / Are sentimental oaks.

Caput XI : H. travels through the Teutoburg Forest . In Detmold , money is being collected for the construction of the Hermann monument that has just started . H. also donates and fantasizes about what would have happened if the Cheruscan Arminius had not defeated the Romans: Roman culture would have permeated German intellectual life, and instead of three dozen country fathers there would now be at least one real Nero. The caput is - hidden - also an attack on the cultural policy of the 'romantic on the throne', Friedrich Wilhelm IV .; because almost all the personalities named in this context (e.g. Raumer , Hengstenberg ; Birch-Pfeiffer , Schelling , Maßmann , Cornelius ) reside in Berlin.

Caput XII : When the carriage suddenly loses a wheel on a midnight journey in the Teutoburg Forest and a repair break has to be taken, H. gives the hungry howling wolves a satirical acceptance speech, whose ( mutilated ) print in a Allgemeine Zeitung by Georg Friedrich Kolb is known He satirically cites publishers and politicians.

Caput XIII : Near Paderborn a crucifix appears to the traveler in the morning mist. Christ, the “poor Jewish cousin” was less fortunate than H., whom a loving censorship has so far saved from crucifixion.

Caput XIV : H. remembers his old nurse, who told him about sad fairy tales and about the Emperor Rotbart , who lived in Kyffhäuser and was waiting with horse and rider to one day free Germania from her chains.

Caput XV : A fine continuous rain lulls the traveler to sleep. He continues dreaming the old wives' tale of Barbarossa. But then the mythical emperor no longer presents himself as a brave warrior, but as a senile old man who is proud that his flag has not yet been eaten by the moths, but otherwise hardly worries about Germany's inner misery. Since he still lacks a sufficient number of battle horses anyway, he takes his time with the blow and consoled H. with the words: If you don't come today, you will certainly come tomorrow, / The oak grows slowly, / And chi va piano, va sano, that's the name of / The proverb in the Roman Empire.

Caput XVI : H. informs the emperor that between the Middle Ages and modern times, between Barbarossa and 1843, the guillotine ensured the abolition of many crowned heads. The emperor is outraged, speaks of high treason and crimes of majesty, and forbids H. to make further disrespectful speeches. But he doesn't let himself be intimidated: The best thing would be for you to stay at home / Here in old Kyffhäuser - / If I think about it carefully, / So we don't need any emperors.

Caput XVII : Having awakened again from his slumber, H. regrets his quarrel with Kaiser Rotbart. He asks him silently for forgiveness and begs him the old Holy Roman Empire recover because its musty junk and Firlefanze is always better than the present political hybrid that neither meat nor fish was.

Caput XVIII : H. feels trapped in the threatening Prussian fortress of Minden just as Odysseus did back then in the cave of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus. The food and the bed are so bad that he sleeps restlessly and dreams of being chained to a rock like Prometheus and having his liver hacked out by the Prussian eagle.

Caput XIX : After visiting the house where his grandfather was born in Bückeburg, H. travels to Hanover , where King Ernst August, well protected by the cowardice of his subjects, is bored to death and, having got used to the freer Great British [sic] life , is on love to hang yourself.

Caput XX : H. is at the destination of his journey. In Hamburg, he stays with his mother . She immediately puts a hearty meal on the table and asks him, typically a mother, sometimes difficult questions : Does your wife understand housekeeping? (...) Which people will you give preference to? (...) Which party do you belong to with conviction? The son, however, only gives an evasive answer: The fish is good, dear mother, / But you have to eat it in silence; / It's so easy to get a bone in your throat / You mustn't disturb me now.

Caput XXI : H. is having a hard time finding the old places of his youth in Hamburg, as half the city recently fell victim to a fire. However, ample compensation has been collected. All the more mockingly, he mocks himself at the hypocritical self-pity of the Hanseatic people.

Caput XXII : H. looks back nostalgically. Times have changed. The people of Hamburg seem like walking ruins to him and many of his former friends have grown old or are no longer there.

Caput XXIII : H. sings the praises of good food and drink - and his publisher Campe, who invites him to do both. Hammonia , Hamburg's patron saint, appears to him in a blissful mood and takes him to her little room .

Caput XXIV : Hammonia reveals to H. that he was her favorite poet after Klopstock's death, and asks why he is traveling. He confesses to her that his illness and wound are his homesickness and his love of country: The otherwise so light French air / She began to squeeze me; / I had to catch my breath here / In Germany so as not to suffocate.

Caput XXV : The goddess promises to show her visitor the future of Germany if he vows to remain silent. Instead of an oath, she demands a frivolous service of love to seal it: Lift up your robe and put your hand / Down here on my hips / And swear secrecy / In speeches and in writings!

Caput XXVI : With glowing cheeks, Hammonia H. shows her magic kettle , which turns out to be Charlemagne's chamber pot and whose stench is the German fragrance of the future . The amorous goddess hastily closes the lid and surrenders to the poet in a frenzy of wild ecstasy that inspires the genius of the poet to new creative visions. No wonder that at this point the censor steps in and the reader remains unexplained about everything else.

Caput XXVII : At the end of his winter fairy tale, H. drafts an optimistic picture of future generations of readers: The old gender of hypocrisy will disappear, because the youth that understands / The poet's pride and goodness, / And warms himself in his heart, / In his sun mind. - With the last stanzas, Heine places himself in the tradition of Aristophanes and Dante and then addresses the King of Prussia directly: Do not offend living poets / They have flames and weapons / who are more terrible than Jovis Blitz, / Den ja the poet create. The epic closes with the threat of the king's eternal damnation.

shape

In addition to a foreword and an addendum , the work consists of 27 “chapters” ( Capita I - XXVII ) with more than 500 stanzas, each divided into four verses and resembling the so-called Nibelungen strophe . The first and third verses of each stanza have four exaltations, the second and fourth three each. The meter is mainly determined by iambi . The number of unstressed subsidence varies (as is typical for folk songs ), so that the rhythm of the epic is often influenced by the anapaest and thus appears freer and more prosaic . The rhyme scheme is also simple - verses 2 and 4 are connected by a cross rhyme , verses 1 and 3 rhymed. The cadences are distributed according to the same pattern : lines 1 and 3 always end in male form, lines 2 and 4 always end in female form.

reception

Heine's verse epic was very controversial in Germany up to our time. In the century of its creation, in particular, the work was viewed as a “diatribe” by a homeless “traitor to the fatherland”, a bad-mouthed man and a disgrace. This view of Germany. A winter fairy tale was found later, especially during the National Socialist era , which Heine saw as a “Jewish nest dirtier” and banned, exaggerated to the point of stupidly grotesque.

The modern age sees Heine's work - possibly due to a more relaxed relationship to nationalism and German foolishness against the background of European integration - an important political poem in German, sovereign in wit, choice of images and language.

A large part of the appeal that the verse epic exerts today is due to the fact that its message is not one-dimensional, but rather ambiguously expressing the opposites in Heine's thinking. The poet shows himself as a person who loves his homeland and seeks a creative contrast to easy-going France. Just as the giant Antäus ( Caput I , last stanza) needs contact with the earth, Heine also draws his strength and wealth of thoughts from contact with his homeland.

The break that the July Revolution meant for intellectual Germany is exemplarily visible : the fresh wind of freedom suffocates in the reactionary efforts of the Restoration , the "spring" that has already come gives way to a new frosty period of censorship, oppression, persecution and exile; the dream of a democratic Germany will be over for a century.

Germany. A winter fairy tale marks a high point in the political poetry of the Vormärz . It is a commitment to joie de vivre and the presence of equality and freedom , but mere amusement would be an inappropriate reaction because it fails to recognize the enlightening Ernst Heine . While the work was frowned upon for decades as an anti-German pamphlet by the “French elect” Heine, today it is considered a moving, lyrical - and sometimes visionary - testimony of the exile and emigrant Heinrich Heine, in which he foresees the downfall of Prussia through its militarism. Over the centuries it has found more than twenty imitators, the best-known among them Wolf Biermann , who used the motif of the winter fairy tale journey in 1972.

The book was included in the ZEIT library of 100 books .

In 2006, the German director Sönke Wortmann used the title as a model for his documentary Germany. A summer fairy tale . Katja Riemann linked excerpts from Germany. A winter fairy tale with songs from the cycle Die Winterreise zu Winter. A road movie that premiered at the Ruhr Festival in 2012.

literature

Text output

- Heinrich Heine: Germany. A winter fairy tale. (Separate print) Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1844 ( digitized and full text in the German text archive ).

- Heinrich Heine. Historical-critical complete edition of the works. Edited by Manfred Windfuhr. Vol. 4: Atta Troll. A midsummer night's dream / Germany. A winter fairy tale. Arranged by Winfried Woesler. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1985.

- HH: Germany. A winterstory. Edited by Joseph Kiermeier-Debre. Deutsche Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-02632-4 (library of first editions).

- HH: Germany. A winterstory. Edited by Werner Bellmann. Revised edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-15-002253-3 (offers the version of the "Neue Gedichte", 1844, and variants of the separate edition, 1844).

- HH: Germany. A winterstory. Pictures by Hans Traxler. Edited by Werner Bellmann. [Hardcover] Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-010589-7 . As Reclam Taschenbuch No. 20236, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-020236-4 .

Secondary literature

- Werner Bellmann : Heinrich Heine. Germany. A winterstory. Explanations and documents. Revised edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-008150-5 .

- Karlheinz Fingerhut: Heinrich Heine: Germany. A winterstory. (= Basics and thoughts on understanding narrative literature) Diesterweg, Frankfurt a. M. 1992, ISBN 3-425-06167-4 .

- Jost Hermand : Heine's "Winter Tale" - On the topos of the "German misery". In: Discussion Deutsch 8 (1977), Heft 35, pp. 234–249.

- Joseph A. Kruse: A new song about happiness? Heinrich Heines “Germany. A winter fairy tale ”. In: JAK: Heine-Zeit. Stuttgart / Munich 1997. pp. 238-255.

- Fritz Mende : Heine Chronicle. Data on life and work. Hanser, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-446-12087-4 .

- Wolfgang Preisendanz : Heinrich Heine. Work structures and epoch references. Fink, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7705-0888-2 .

- Renate Stauf : Heinrich Heine. Germany. A winterstory. In: Renate Stauf / Cord Berghahn (ed.): Weltliteratur II. A Braunschweig lecture. Bielefeld 2005, pp. 269–284.

- Jürgen Walter: Germany. A winterstory. In: Jürgen Brummack (Ed.): Heinrich Heine. Epoch - work - effect. Beck, Munich 1980, pp. 238-254.

Web links

- Germany. A winter fairy tale in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Full text for the Gutenberg-DE project

- Germany. A winter fairy tale as a public domain audio book at LibriVox

Footnotes

- ↑ In the original orthography the title was: Germany. A winter fairy tale .

- ↑ The journey began on October 21 and ends on December 16, 1843.

- ↑ For the exact route, cf. below the “overview” for “content”.

- ↑ When meter however, the similarity ends, because the Atta Troll used trochaics , the Winter's Tale , however iambs and anapaests .

- ↑ So Heine in a letter to his publisher Campe on February 20, 1844.

- ↑ So Campe, quoted from Klaus Briegleb (ed.), Heinrich Heine. Works in four volumes. Hanser, Munich, 1968-1976, Volume 4, p. 608.

- ↑ One sheet corresponds to 16 printed pages.

- ^ Foreword to Germany. A winterstory.

- ↑ So Heine wrote to Mathilde Heine on October 28, 1843 and went on: “I am completely exhausted. I had a lot of hardship and bad weather. "

- ↑ See Fritz Mende: Heine Chronik. Hanser, Munich 1975, p. 169.

- ^ From Heine's preface to Germany. A winter fairy tale .

- ↑ Although, strictly speaking from a literary perspective, the traveler and the author of the epic verse are not congruent, on the one hand the autobiographical character of the text is so obvious and, on the other hand, terms such as narrator, lyrical self and protagonist are also so implausible that in the following it is For the sake of formal simplicity, it should exceptionally be allowed to regard author and narrator as more or less identical and to shorten them to a neutral "H."

- ↑ "The land belongs to the French and Russians, / The sea belongs to the British, / But we own in the air of dreams, / The rule is undisputed." Heinrich Heine: Germany. A winterstory. In: New Poems. Hoffmann and Campe, 1844, accessed December 15, 2017 .

- ↑ Allusion to literary wage laks.

- ↑ Allusion to the legal philosopher Eduard Gans, who was friends with Heine .

- ↑ During his student days in Göttingen, Heine had joined the Landsmannschaft (later Corps) Guestphalia.

- ↑ "If you go slowly, you are safe."

- ↑ Caput XIX is primarily aimed at Ernst August's breach of the constitution in 1837, against which the seven Göttingen professors opposed.

- ↑ The supplementary foreword was written by Heine on September 17, 1844. It deals with his reactions to the censorship, anticipating the possible objections he is expected to have to his work, and invalidating them.

- ↑ The addendum to “Germany” bears the subtitle Farewell to Paris and consists of 11 further stanzas that name and comment on the occasion and the duration of the trip.

- ↑ Cf. Christoph Siegrist , "Afterword" to Christoph Siegrist (Ed.): Heinrich Heine. Works. Insel, Frankfurt 1968, Volume I, Page 502.