Arminius

Arminius (in some sources also Armenius * 17 BC .; † about 21 AD...) Was a prince of the Cherusci , which the Romans in 9 AD in the.. Varusschlacht with the destruction of three legions one of their most devastating defeats. The ancient sources offer little biographical information about Arminius. The post-ancient image of the Cheruscan prince is primarily determined by the formula “Liberator of Germania” coined by Tacitus .

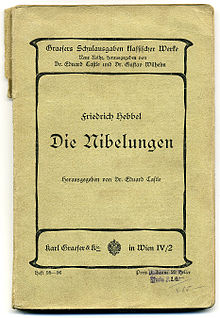

The image of Arminius was by no means uniform before the 18th century. The humanists made him the first German. In the confessional disputes, he was captured by the Protestant and Catholic sides. In Germany, Hermann the Cheruscan , based on Arminius as a historical person, became a national myth and symbol and part of the German founding myth from the second half of the 18th century . It was only in the 1970s that this Arminius image was slowly replaced by a more sober approach in historical studies. Arminius has since been viewed by parts of the research as the leader of a revolt by Germanic auxiliaries in Roman service. His Germanic name is unknown, which is why historical parallels to the dragon slayer Siegfried from the Nibelungenlied have been speculated. The Arminius material was often used in operas, plays, poems, songs or novels, including Lohenstein's baroque novel Großmuethiger Feldherr Arminius (1689/90), Klopstock's “Hermann Barditen ” (1769–1787) and Kleist's drama Hermannschlacht (1808 / 09).

Life until the Varus Battle

Origin and youth

Only a few biographical details about Arminius are known until the Varus Battle. Arminius came from one of the leading families of his tribe. He was around 18/17 BC. Born as the son of the Cheruscan Sigimer / Segimer , who had a leading position in his tribe. Velleius Paterculus calls the father of Arminius princeps gentis eius ("first of his tribe"), which is usually translated with the etymologically similar name "prince". The name of his mother, who lived in AD 16, is not mentioned. Arminius' father, like his uncle Inguiomer , sided with the Romans and led the pro-Roman party under the Cheruscans. Just like his brother Flavus , Arminius served as leader of Germanic associations (ductor popularium) for a long time in the Roman army and thus became familiar with the Roman military system. In this function he served during the campaign (prior militia) that preceded the Pannonia War from late autumn AD 4 to at least AD 6 in the Roman camp. He acquired Roman citizenship and the rank of knight and learned the Latin language. Arminius was probably involved with his association in the suppression of the Pannonian uprising in the years 6–7 AD . Repeated assumptions that Arminius made a career as a “professional officer” in the Roman military or commanded “a force of Cheruscans that came very close to the regular auxiliary units” are unprovable or anachronistic assumptions.

Around the year 7/8 AD Arminius returned to the Cheruscan tribal area. At that time Arminius by no means had sole power with the Cheruscans. At that time he was confronted with disputes within the Cheruscan leadership. Segestes , the father of Thusnelda , was against a connection between his daughter and Arminius, who probably became his wife at that time.

Revolt against Varus

When the governor ( legatus Augusti pro praetore) Publius Quinctilius Varus wanted to advance into the Cheruscan region as far as the Weser , Arminius saw the time for an uprising in the autumn of 9 AD. He stayed with his like-minded comrades, of whom Segimer is called, consciously in the Varus camp, often taking part in his table and trying to win the governor's trust. When Varus was on his way to his winter camp, he was informed of unrest. The warning given by Prince Segestes on the eve of his departure to put Arminius in chains because he was planning to betray Rome was not taken seriously by Varus. The accusation of naive trust and lack of caution on the part of Varus towards Arminius, which some sources raise, is in part relativized in modern history. Varus acted as usual in the provincialization of a conquered area. Arminius was probably seen by Varus as a Roman ally due to his Roman citizenship and his knighthood, who, as the leader of the urgently needed Germanic auxiliary troops, could help to keep the situation calm.

On the way to the uprising reported by the Germanic peoples, the Romans had to go through a little known area, where they were ambushed. Arminius defeated the Roman occupying power in the Varus Battle with a surprising blow . The location of the fighting remains controversial. The 17th , 18th and 19th legions as well as six cohorts and three ales ( auxiliaries ) perished at the Saltus Teutoburgiensis ; Varus took his own life. What specific role Arminius played during the battle is uncertain, the only thing that is certain is that he was the commander-in-chief of the Teutons, to whom he spoke on the battlefield. Since Theodor Mommsen it has been suspected on the basis of found coins that the battle took place in the Bramsche-Kalkriese area. Excavations have been carried out in this area since 1987.

Based on his source analysis, Dieter Timpe concludes that immediately after the Varus defeat there was a "westward offensive" by the rebellious Teutons, which the more recent research rejects. The consequences of the defeat were devastating. All Roman forts in Germania on the right bank of the Rhine were conquered with the exception of one base that was identified with Aliso , which was not reliably located . Arminius had the heads of the dead carried on lances to the enemy wall in order to break the tenacity of the besieged. When the Germanic tribes heard the rumor that Tiberius was approaching with an army, many of them withdrew. The Roman fort garrison could only fight their way to the Rhine in the spring of 10.

Motives for the uprising

According to Tacitus, Arminius appealed to the fatherland, ancestors, tradition, fame and freedom. Ancient historiography sees the possible reasons for the uprising in the more restrictive administration and jurisdiction of the Varus, the associated loss of influence and power, the demands for tribute and the arrogant and insensitive demeanor of Varus and other Romans towards the Cheruscans and others, as attested by the sources Uprising involved tribes. The majority of the tribes and chiefs of the Germanic tribes were very reserved towards Roman customs and traditions. Arminius may also have sought power over other Cheruscan and other tribes involved in the uprising or may have been guided by a concept of honor. However, the attack on the army of Varus was not a unifying act of community of the Germanic peoples, but essentially the tribes from the north-western low mountain range between Ems and Weser were involved. Frisians and perhaps also Chauken remained loyal to Rome after the year 9.

Life after the Varus Battle

Further conflicts with Rome

After the defeat of Varus, Augustus ordered the withdrawal of the bodyguard. Dieter Timpe therefore considered connections between Arminius and the bodyguard in Rome to be likely, which would have prompted Augustus to dismiss them. However, this thesis contradicts the return of the Germanic bodyguards to Rome a few years later, which is attested by Tacitus. The Roman defeat meant a major setback, but not the final retreat of the Roman policy towards Germania to the Rhine border. Under the military leadership of Tiberius, the fleet was reinstated, the three lost legions were immediately replaced and the total number of legions stationed on the Rhine increased to eight. The contemporary witness Velleius Paterculus reports of significant military activities under the command of Tiberius, during which large parts of Germania were devastated. However, the results of the campaigns are presented contradictingly in the other sources, which is why it is not certain what Tiberius achieved in the years 10 to 12. He is said to have tried to penetrate Germania only with extreme caution and strict discipline.

Probably in anticipation of further disputes with Rome, Arminius therefore sought an alliance with the Marcomann king Marbod ; the severed head of the Varus was sent to Marbod. Marbod refused Arminius' offer of alliance and sent the head to Augustus. The princeps is said to have torn his clothes when he learned of the defeat and exclaimed: “Quintilius Varus, give me the legions back!” Augustus had the head of Varus honored in the family grave.

In the year 13 Augustus Germanicus , the son of Drusus adopted by Tiberius, handed over the command of the troops. With eight of 25 legions, he commanded almost a third of the entire Roman armed forces and thus a much larger army than Varus.

The ancient authors do not provide any concrete figures on the Arminius army, which is why its strength during the Germanicus campaigns (14 to 16 AD) was assessed differently in research. Kurt Pastenaci has assumed a number of 40,000 men, more recent estimates assume around 50,000 men, with considerable scope upwards and downwards.

In the years 14 to 16 AD Arminius led an expanded coalition of Germanic tribes in defense of the Roman reconquest expeditions led by Germanicus. Despite statements to the contrary, the greatest success of the Roman enterprise was only the capture of Thusnelda , the wife of Arminius.

Thusnelda was captured by Germanicus in 15 AD when her father Segestes handed her over to the Romans. She was pregnant at the time and gave birth to her son Thumelicus in captivity , who grew up in Ravenna . The report announced by Tacitus about his further fate has not survived; perhaps he died at the time of a "gap" in the annals, around 30–31 AD. It is possible that he was already dead in 47 AD when the Cheruscans asked Emperor Claudius the Italicus to be king. However, there is no reliable evidence.

In the first battle, not far from the site of the Varus Battle, Arminius lured the Roman cavalry into a trap. However, Germanicus had brought his legions in time, so that the fight ended in a draw. Then Germanicus withdrew to the Ems, where he placed half of his army under the leadership of Caecina ; this army was to march over the long bridges to Vetera and reach the Rhine along the North Sea coast. Arminius overtook Caecina's legions in forced marches. The result was a battle lasting several days , which, as described by Tacitus, was initially very similar to the Varus Battle. But on the last day, when the Romans sat defeated and discouraged in their camp, Arminius' uncle advised Inguiomer to attack the camp. Arminius advocated sticking to the tried and tested tactic of attacking the marching army, but could not prevail. In the following storm on the camp, the Teutons suffered a setback. Arminius was unharmed in battle, Inguiomer was badly wounded, and the remnants of Caecina's army were able to escape across the Rhine.

Battles of the year 16 AD

In 16 AD, Germanicus undertook a new campaign with eight legions against the Cheruscans and their allies in order to try again to conquer Germania. The Cherusci withdrew behind the Weser and the Romans followed them. Before the battle, Arminius and his brother Flavus, who was in Roman service, allegedly had a dispute, calling to each other from opposite sides of the Weser. According to Tacitus, in this conversation Arminius represented the sacred law of the fatherland, the ancient freedom and the Germanic gods, while the Rome-friendly Flavus held up to his brother the greatness of Rome, the power of the emperor and the severe punishments for insurgents. Flavus assured that Thusnelda and her son would be treated well. It did not come to an agreement, on the contrary, Flavus is said to have been held back from a battle by a comrade.

The following day Germanicus crossed the Weser and prepared everything for the attack. A day later the armies met at Idistaviso . Tacitus describes the battle as a great Roman victory, Arminius was badly wounded in the battle and could only escape capture by smearing his own blood on his face. Despite great losses, the Germans were still strong and bellicose enough to face the Romans again. With the border wall of the Angrivarians, the Germanic tribes again chose a favorable terrain between a river and forests. In the battle of the Angrivarian Wall , Arminius showed himself to be weakened, either because of the constant danger or because the wound prevented him. Although the Romans were victorious, Germanicus felt compelled to leave Germania again in summer, long before a planned retreat to winter camp. With his retreat to the Rhine, the Roman attempt at conquest had finally failed. The stubborn Germanic resistance and the associated Roman losses explain the recall of Germanicus by the new emperor Tiberius and thus the renunciation of another offensive Roman border policy. Tiberius thought it best to leave the Teutons to their internal quarrels.

Internal tribal conflicts and death

In the years 9 to 16 AD, the allies of Arminius, in addition to the Cheruscans, included the Brukterians , the Usipeters , Chatti , Chattuarians , Tubanten , Angrivarians , Mattiakers and Landers . In the spring of 17 AD there was a battle against Marbod , from whose sphere of influence the Semnones and Lombards had defected to Arminius. On the other hand, Inguiomer, Arminius' uncle, went over to Marbod. Marbod was defeated by Arminius and had to retreat to Bohemia . However, Arminius could not take advantage of his military success because he could not penetrate the natural fortress of Bohemia. After that he had to deal with internal Germanic rivalries and numerous changing pro and anti-Roman positions on the Germanic side. Mainly (but not always) on the side of the Romans fought the Ubier , the Batavians and partly also the Frisians .

The Marbod coalition did not strive for a large empire of its own, but rather accused Arminius of striving for royal rule over one. Rome formally refused an offer by the Chattenfürst Adgandestrius to have Arminius killed with poison; it is not known whether Rome could have tried to bring about his death. The offer submitted by letter not only illustrates further tensions in the leadership clan, but also a break in the Cheruscan-Chatti alliance. In the year 21 Arminius was murdered by relatives.

Sources

The knowledge about Arminius is based exclusively on Roman written sources and archaeological finds, since the Germanic peoples had no written culture . Contemporary historiography held that treason had brought Varus down and was not interested in the person of Arminius himself. A first incidental mention of Arminius can be found in Strabo . Velleius Paterculus sees Varus as the main responsible for the lost battle. He cleverly combines the degradation of Varus with a characterization of Arminius, which shows numerous topoi , which seem to be understood as characteristic features that often only reflect the ignorance about the actual circumstances. Topoi were often used in ancient literature, especially in ethnography , to describe " barbarians ". The Germans involved in the uprising are characterized as wild and mendacious. Florus reports that the rebellious Germans tore out the Roman soldiers' eyes and tongue while they were alive.

Only Tacitus deals intensively with Arminius apart and measure historical significance to him. He criticizes the silence of contemporary authors with regard to Arminius:

- "Greek historiography does not know him, and with the Romans he did not play the role it deserves, since we praise the old history and are indifferent to the new" .

The characterization of Arminius in Tacitus is not as sober as that of Velleius Paterculus, since Tacitus, unlike him, holds Arminius responsible for the downfall of the legions. However, Tacitus also makes use of the usual topoi in his portrayal of Arminius: Arminius is portrayed as a cunning schemer who prides himself on having defeated the Romans in an honest fight, while in Rome it was common knowledge that Varus had been ambushed. Gandestrius, who asks for poison in Rome in order to kill Arminius, is also described as insidious in that his offer is countered by the Roman position that Rome would not defeat its opponents with deceit and deceit, but in open combat. Arminius is also portrayed as spiteful: he mocks his Rome-friendly brother Flavus during a dispute on the Weser because of his lost eye. Tacitus characterizes Arminius in negative contrast to Segestes, Marbod and Flavus, who at least at times represented a position that was friendly to Rome.

Geographical descriptions of the battlefields, which were characterized, for example, by a cold, damp climate, dense forests and boggy subsoil, are generally viewed in research as topical ideas of the Romans for northern countries, which the authors used by means of an ecphrase . Depictions of battles that followed the Varus defeat, such as the Caecina battle, were probably modeled by ancient historians on the basis of the detailed reports on the Varus battle. This made it possible to directly compare events such as Caecina's successful escape in contrast to Varus, who lost his life on the battlefield. These battle representations are therefore considered unhistorical.

The situation described by Tacitus outburst (ira) of Arminius after the capture of his wife by the Romans with brief madness (brevis insania) is probably a literary fiction , as views herein the then very popular Stoic school reflect what the uncontrolled appearance of emotions as un-Roman and the mark of a tyrant or barbarian .

The social structure of the Cherusci is only vaguely handed down. Tacitus gave his audience associations with the end of their own tyrannical royal times through the concept of royal rule and his reference to the Cheruscans' desire for freedom . He indicates a noble rule of the Cherusci, which Arminius wanted to abolish. The official powers of the tribal leader are not described. The term prince ( princeps ) , by which Arminius is characterized, denotes a liberal-republican rule in contrast to the term rex (king), with which a tyrannical rule would be described.

Origin of name

In addition to the search for the location of the Varus Battle, the search for the real name of Arminius is the most frequently discussed question in Arminius research. The ancient historians Strabo , Cassius Dio and the Tacitus manuscripts suggest the spelling of Armenius . Velleius Paterculus (around 29/30 AD) passed on the name "Arminius, son of Sigimer ", without further additions:

- “At that time there was a young man of noble descent who was personally brave, quick to learn and gifted beyond the barbarian standards; his name was Arminius, the son of Sigimer, a prince of this tribe. "

According to common Roman usage, Armenius referred to a resident of Armenia . In research it was therefore assumed that “Arminius” was a cognomen and could therefore mean, for example, “the Armenian” and thus refer to a general responsible for Armenia. However, it was objected to this assumption that the corresponding Latin name was not Armenius , but Armenicus or Armeniacus , as the nicknames later given to Lucius Verus and Mark Aurel for a victory over Armenia show. A derivation from the geographical term "Armenia" is problematic with the far-reaching consequences for the biography of the young Arminius. In addition, Velleius never passed down the form of the name Armenius, but always only Arminius.

The name Arminius therefore seems to be originally Roman and cannot be derived from a Cheruscan name. Since it was customary at the time of Augustus for a non-Roman to take the name of the Roman who had given him this right when transferring civil rights, it is also assumed that an Etruscan knight dynasty was the Arminii namesake and that Arminius was therefore a nomen gentile act.

The later widespread name "Hermann", from Germ. * Charioman "Heer-mann" lat. Dux belli , for Arminius is mostly attributed to Martin Luther . Luther confessed: “If I am a poet, I want to celebrate him. I got it from hertzen lib ” . However, Johannes Aventinus (1526) could also be the first evidence for the naming . Hermann is thus a product from the time of the beginning Germanic reception of humanism .

Arminius – Siegfried

In 1837 the German scholar Adolf Giesebrecht tried to show that the Nibelungenlied had its historical origin in the Arminius story and that Arminius and Siegfried the Dragon Slayer were one and the same person. Karl Ludwig Sand , the murderer of the writer August von Kotzebue , had already expressed this conviction shortly before his execution in 1820:

- "If German art wants to give us a sublime concept of freedom, it should represent our Hermann, the savior of the fatherland, strong and great, as the Nibelungenlied calls him under the name Siegfried, who is none other than our Hermann".

In the 20th century, this thesis was advocated or at least considered by well-known scientists - among the best-known are Dieter Timpe , Ernst Bickel and Otto Höfler . Proponents of a parallel between Arminius and Siegfried justify this on the one hand with the name Sigimer = Siegmar of the father of Arminius, whose root word has been passed on from generation to generation (as for example with Segest and Segimund). By passing on the root word "Sieg-" and assuming that Arminius was his firstborn, it has been assumed that the Germanic name of Arminius was Siegfried. Parallels between Arminius and Siegfried were seen in the fact that both figures were insidiously murdered by relatives. It has also been suggested to associate the invisibility cloak with the fact that Arminius lived like a Roman for years and was therefore invisible to his people. The Hildesheim silver treasure was already interpreted by Höfler as Varus tableware and Arminius' loot of victory. The scaled, almost invulnerable dragon, on the other hand, is a mythical reshaping of the armored legionnaires of Varus. In addition, the account of Tacitus, according to which Arminius was still the subject of Germanic heroic songs at the beginning of the 2nd century and Arminius' deeds were praised and his tragic and all too early death was mourned, was equated with a preliminary form of the Nibelungenlied. However, the interpretation of this Tacitus passage is controversial, as it is uncertain whether the earliest Germanic heroic songs are actually being depicted here or whether Tacitus merely takes up a topos of ancient ethnography. The chants described by Tacitus, in which Arminius was remembered, were in part viewed as prize songs that need not necessarily have been pre-forms of heroic poetry.

The hypothesis published by Höfler between 1959 and 1978 about the roots of the figure of the dragon fight in the victor of the Varus Battle met with both acceptance and harsh rejection within the experts. Especially outside of Old German Studies, historians are mostly very critical of the hypothesis and understand it as an imaginative form of scientific positivism in the time when German studies were founded, which was shaped by the Romantic era . From the localization of the Varus Battle to the equation of Arminius and Siegfried to the reinterpretation of the battle as a dragon fight, not a single link in the chain of arguments is in fact secured. Rather, guesswork is based on guesswork, an approach that is considered methodologically problematic. The proponents of the Siegfried hypothesis are also accused of being too selective when evaluating the saga and of considering anything that does not match their assumption to be a later invention - there is a risk of circular reasoning.

Furthermore, the reliability of oral tradition that was written down later is rated less than it was three decades ago. A connection between the victory of Arminius and the Nibelungenlied therefore remains very questionable, especially because of the assumption that there is more than twelve centuries between the historical event and its written down. The Arminius-Siegfried connection is therefore regarded by the vast majority of today's specialist scientists as an unprovable speculation.

reception

By the end of the 18th century

The Cheruscan prince played no significant role in the literature of antiquity and the Middle Ages. Only the rediscovery of the Germania of Tacitus in 1455 in the Hersfeld monastery and the annals with the sections about Arminius in the Corvey monastery in 1507 aroused interest in the Germanic peoples and in Arminius. Since the age of humanism, both works have formed one of the most important foundations for the German national consciousness that developed around the person of Arminius. Tacitus wrote about Arminius:

- "He was undisputedly the liberator of Germania" (liberator haud dubie Germaniae).

With reference to these words, Arminius was elevated to a national symbol figure in German literature since the 16th century.

As early as 1529, Ulrich von Hutten praised the Cheruscan Arminius in his Arminius dialogue as the “first defender of the fatherland” in order to ascribe a common cultural identity as well as moral and military superiority to the Germans of his time . In this dialogue, Arminius is placed in line with the greatest generals of antiquity - Alexander the Great , Hannibal and Scipio the Elder . At the end of this dialogue, Arminius appears worthy of becoming "King of the Germans", not just one king among many tribes. Beatus Rhenanus and Philipp Melanchthon worked on this topic in a similar way. Reformatory circles saw in Arminius' struggle against Roman rule a historical parallel for their conflict with the Roman Church. Between 1550 and 1650 Arminius is regarded as a model of virtue and heroism. The Varus Battle hardly played a role at this time.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, a large number of other versions were created, which were increasingly written as entertainment literature, in which the decorations increased and the historical Arminius took a back seat. The idea of presenting the Arminius material on stage came from France, where Jean-Galbert de Campistron premiered a tragedy in Paris in 1684 . The French turned the Arminius material into a story of love rivalries about Thusnelda. The heroes of the authors were great personalities, who embodied noble virtues of courageous determination, generosity and willingness to make sacrifices on the way to great love. In France these virtues were praised all the more, the more the old nobility was put on the defensive by French royalty. In the Baroque era , the French also saw themselves as descendants of the Teutons and were not yet bothered by the fact that the Germans, for their part, saw Arminius as a liberator of the fatherland. The libretto by Giovanni Claudio Pasquinis focuses on the lovers Arminius and Thusnelda, the main opponent is Segestes, who strives for an understanding with the Romans. Especially in the Baroque era, the audience was essentially interested in the tragic love story of Arminius and Thusnelda. Antagonists are not Varus or other Romans, but always the Teutonic Segestes, who betrays his countrymen and surrenders his own daughter to the enemy.

A significant historical interpretation of the Arminius material in the Baroque era is the courtly historical novel Großmuethiger Feldherr Arminius by Daniel Casper von Lohenstein , published posthumously in 1689/90 . In the more than 3000-page work, the German Arminius symbolizes the then reigning Emperor Leopold I. Obviously, Lohenstein sees the “generous” general Arminius and his clever, balancing policy as a historical model for a strong emperor who is able to unite the imperial estates behind him. In the late 17th century, conflicting particular interests of the sovereigns - similar to the disputes among the Germanic tribes - often led to foreign policy threats from France and the Ottoman Empire (in Lohenstein's death year 1683, the Turks stood before Vienna). Lohenstein describes the present in the guise of old history, although he aligns the plot very precisely with the course of the historical events after the Varus Battle, handed down by Tacitus.

As a symbolic figure of patriotic virtues, old German heroism and independent national culture, Arminius finds its way into the poetry of the Ode Hermann and Thusnelda of 1752 and later in the three bardites Hermanns Schlacht (1769), Hermann und die Fürsten (1784) and finally Hermanns Tod (1787) by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock . With the three bardites, Klopstock wanted to tie in with the battle chants (barditus) handed down by Tacitus . In describing the events between the Varus Battle and the murder of Hermann, they not only use a new lyrical, declamatory tone, but also have an especially operatic-stylized effect in the feelings expressed. The blood motif often found in Klopstock's bardites glorifies the willingness to sacrifice one's own life for the fatherland:

“ But now sing to me the song of those who loved their homeland more than their lives. Cause i'm dying! All: O fatherland! O fatherland! More than mother, and wife and bride! More than a blooming son With his first weapons! "

In Klopstock's bardites, the religious-patriotic chants of consecration, Arminius is thus stylized as a model of true patriotism.

In the 18th century, further political aspects were added to the implementation of the Arminius material, especially the struggle of particularism against central authority. The idea that Arminius had been prevented by his relatives from establishing a permanent central authority was seen as the tragic and admonishing example of his time, according to Justus Möser , who wanted to support the political cohesion of the German territories internally with literature.

The Arminius fabric inspired the entire German intellectual elite in the 17th and especially in the 18th century: Johann Elias Schlegel (1743), Justus Möser (1749), Christoph Otto von Schönaich (1751), Christoph Martin Wieland (1751), Jakob Bodmer (1756) , Friedrich Hölderlin (1796) and finally Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , who worked on a design in 1801. The 18th century was also the climax of the Arminius operas with at least 37 titles.

National myth in the 19th century

Especially in the 19th century, the person of Arminius as "Hermann the Cheruscan" was increasingly appropriated by German national chauvinists . Starting with the wars of liberation against the French occupation, the demarcation to the outside was considered a central topic of the Arminius material. In his momentous book Deutsches Volksthum , which was published for the first time in 1810, Friedrich Ludwig Jahn thought about how with the memory of Hermann, whom he called “People's Savior”, as the victor in the “Hermann Battle” and of Heinrich the Great (919-936) as National revival celebrations can be set up for the Hungarians as “state saviors”. The painter Caspar David Friedrich , a supporter of the patriotic movement of the German fraternity , for whom Jahn's book became compulsory reading, alluded to the political events in the symbolic imagery of his work, tombs of old heroes . During the wars against Napoleon, the victory of Arminius, interpreted as the Battle of Hermann, became a symbol of self-assertion and liberation from the French for the Germans. In 1814, the first anniversary of the Leipzig Völkerschlacht was celebrated by the Germans, who called themselves “Hermann's grandchildren”, as a national festival, the “Second Herrmann's Battle ”.

The most famous adaptation of the Arminius motif of this time, the Hermannsschlacht Heinrich von Kleist , which he wrote under the impression of the Napoleonic occupation of part of Germany in 1808, links the political myth with the current political situation. The Romans symbolize the Napoleonic occupiers and are subtly described, while the Cherusci represent Prussia on the opposite side. Among the divided German tribal princes only the “Prussian” Arminius recognized the need for Germanic resistance. In this play, Hermann is portrayed in a noble way, politically self-confident, energetic and effective.

The Hermann Battle was premiered in the Breslau City Theater on October 18, 1860, on the anniversary of the Leipzig Battle of the Nations . From the Franco-German Wars and the establishment of the German Empire, the work was staged more frequently. At the beginning of the First World War , messengers in the Berlin Schillertheater were still announcing victory reports from the French front between the acts of this drama.

The reference to France was clearer than with Kleist in contemporary poetry , which had German soldiers campaign against French troops with reference to the "Hermannschlacht". German soldiers were called "Cheruscans" or "Hermann's grandchildren". In 1835, Christian Dietrich Grabbe wrote a play under the same title , with which he wanted to express his longing for a free, unified Germany and emphasize the importance of Arminius for German history. Grabbes The Hermann Battle was first performed in 1936. For National Socialism it was attractive because it was "about the relationship between the leader and the people [...] as a grown, binding community of life and fate".

The representation of Arminius in the opera also changed in the 19th century. In the years 1813 to 1850, when twelve more Arminius operas were written, the main theme was no longer the love story between Arminius and Thusnelda, but the "liberation of Germany" by the freedom and national hero Arminius. Three operas between 1835 and 1848 alone bear the title Hermannsschlacht . Furthermore, the composer Franz Volkert called his opera Hermann, Germania's Retter , premiered in Vienna in 1813 , and the Arminius opera, premiered by Hermann Küster in Berlin in 1850, is called Herrmann der Deutsche . Max Bruch wrote an oratorio Arminius in 1877 , which gets by without any ideologization and is still performed today.

In the fine arts, too, the Arminius material was processed in a nationalist function. As early as 1768, Cornelius von Ayrenhoff asked all of Germany's princes to erect a monument to Arminius in order to make the nation better known with the greatest of its heroes and to kindle the fire of bravery and extinct patriotism in it through the deeds of their forefathers . As a result, numerous monuments were planned, but not realized. An exception was the suggestion of the sculptor Ernst von Bandel , who wanted to honor Arminius because of his patriotic sentiments. Bandel assumed that the battle took place in the Teutoburg Forest . The decision to build the monument on the Grotenburg was made for practical and aesthetic reasons. In 1838 the construction of the Hermann monument began. Four years later, on the instructions of the Bavarian King Ludwig I, the Hermann Battle was immortalized in stone in the gable of the Walhalla, which was newly built on the Danube .

Shortly after the start of construction on the Hermann monument, Heinrich Heine's work Germany appeared in 1844 . A winter fairy tale in which he ridiculed the national enthusiasm for the Arminius myth:

- "If Hermann did not win the battle / with his blond hordes / German freedom would no longer exist / we would have become Roman!"

Very few contemporaries were aware of the deeper ironic meaning of these verses.

The reaction phase and financial difficulties brought the construction of the monument to a standstill after the revolution from 1848/49 to 1863. The monument project only became popular again with the establishment of the German Empire after the Franco-German War (1870–1871) and the national feeling that came back with it. Both the new German Reichstag and Kaiser Wilhelm I made it possible to inaugurate the monument with large donations in 1875. The seven meter long sword on the Hermann monument bears the inscription: " German unity my strength - my strength Germany's power " (see also Hermann monument ).

Gymnastics clubs, fraternities and also some Masonic lodges showed their national commitment by naming themselves after Arminius. In schoolbooks that appeared around 1871, the Varus Battle and Arminius as the leading national figure are always cited as the first event in German history and nation building. The Arminius cult increased during this time to national superiority claims over other nations. In 1872 Felix Dahn said in his song of victory after the Varus Battle : “Hail the hero Armin. Lift him up on the shield. Show him to the immortal ancestors: Such leaders as give us, Wodan, more - and the world, it belongs to the Teutons! "As a symbol of the" German "par excellence, Hermann was also used by emigrants in the 19th century as a reminder of their homeland, for example through the erection of a Hermann monument in New Ulm in southern Minnesota . The founders expressed " their commitment [...] to the German community of descent ".

Arminius picture until the middle of the 20th century

The enthusiasm for Arminius increased in the following decades and "reached its peak" in 1909. The 1900 anniversary of the battle was held in Detmold. In the Weimar Republic , the Hermannslauf served the German gymnastics club as an expression of national unity and less as a desire for military sovereignty. In 1925 a total of 120,000 gymnasts from all parts of the German Empire competed in a star and relay race. The Hermann myth, however, experienced a significant shift in the 1920s under the influence of the Versailles Treaty, which was perceived as a national disgrace . Away from the celebration of a triumphant victory, towards the admonishing contemplation of the tragic image of a hero brought to the fruit of his victory through inner dissension and murdered in a murderous manner, as which both Hermann and Siegfried are now interpreted under the sign of the stab in the back. In the crisis year of 1923, the publicist Otto Ernst Hesse wrote:

- And yet it is hardly necessary to heroize Arminius. The opponents have already done it themselves. what we have to read is Hermann's tragedy - the tragedy of Germany and Germanness, which begins where the German people enter history .

The tragic Arminius interpretation achieved particular impact in the völkisch - nationalist discourse of the so-called Conservative Revolution and its pioneer Arthur Moeller van den Bruck . In his work The Third Reich , published in 1923, the Germanic peoples are said to have an allegedly racially based “joy in fighting and fighting ability”, and Arminius appears as their chief witness. As a charismatic leader, he tore his people out of “celebrations, idleness and indolence”, and only joyful submission to his will brought supposedly true freedom to the Germans of the first century. This anti-democratic misrepresentation of history , which was widespread among the right-wing enemies of the Weimar Republic, was all too easily reinterpreted in the National Socialist sense as a model for future German unity and strength under Adolf Hitler's leadership . In the election campaign for the state elections in Lippe in 1933 , the last before the so-called “ seizure of power ”, the National Socialists made extensive use of the Hermann myth. An election poster, for example, showed Hitler with his arms crossed and a determined look against the background of the Hermann monument and a rising sun with the swastika in the middle . The expressive motif no longer needed a text.

After 1933, the person of Arminius was still frequently received in literary terms, especially under the aspect of popular history. However, the National Socialists distanced themselves from the figure of Arminius, as the consolidated National Socialist rule found its leading figure in the “Führer” himself. In the National Socialist ideology, the Führer derived the legitimation of his political and military action not from history, but from his own will. In addition to ideological aspects, foreign policy aspects also played a role in the distancing from Arminius, especially the consideration for the Italian allies. In 1936, during a state visit by Benito Mussolini, the Hermannsdenkmal was removed from the program on the instructions of the Reich Chancellery, as it was feared that it might offend him. During the entire period of National Socialism, there was no spectacular major event at the Hermannsdenkmal. The lack of interest in the figure of Arminius can also be seen in the fact that not a single Wehrmacht or SS unit, campaign plan, command company or ship bore the name Arminius. The tapestry designs by Werner Peiner were an exception . In 1940, Hitler commissioned eight tapestries, which were to be destined for the marble gallery of the new Reich Chancellery, to depict eight great battles, beginning with the Hermannschlacht. The political scientist Herfried Münkler attributes the National Socialists' low interest in the figure of Arminius to the fact that “their interest was more in Germanic expansion than in the defense of the“ home soil ”.” When the Allied armies advanced into Germany in 1944 it was too late for a revival of the Arminius cult.

Modern Arminius reception

As in the 19th century, historical novels have been published in considerable numbers since Kalkriese was identified as a battleground. Among the narrative works, at least 66 titles, most of them published after 1980, could be counted after the Second World War.

There are also numerous other arrangements, some of which do not focus on the person of Arminius but on the Varus Battle. This battle was filmed three times. The silent film Die Hermannschlacht, made by Leo König (premiered in 1924), was under nationalist and anti-French impressions during the war against the Ruhr . The film by Alessandro Blasetti La corona di ferro (premiered in 1941) has little in common with the historical Arminius. In 1967 Ferdy Baldwin shot the sandal film Hermann the Cherusker - The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest . The joint production Die Herrmannschlacht premiered in 1995 in Düsseldorf. The entertainment film takes place both in ancient times and in the 19th century.

For the 125th anniversary celebration on August 16, 2000, the Hermannsdenkmal was not so much a site of national identification, but rather was used for marketing. The celebration took place without national celebrities and received hardly any response in the national press. In 1999, a beer brand was advertised with the Arminius on the memorial by wearing a huge football jersey. Arminius or the Hermannsdenkmal is no longer seen as an identification for the German nation. However, forms of nationalistic Arminius veneration have persisted in extreme positions to this day. In 2009, right-wing extremists addressed Arminius on the occasion of the two thousandth anniversary of the battle. For them, within the framework of their ideological ideas, he was a defender of the homeland against foreign intruders. As a result, they portrayed Arminius as a “resistance fighter” against migrants and the United States, which was seen as the “new Rome”.

Arminius in recent research

Controversy

In recent research, two theses about Arminius in particular have been discussed controversially:

According to Dieter Timpe , whose Arminius studies published in 1970 initiated a new phase of relevant research on Arminius, Arminius was a Roman commander under oath, and the uprising thus became a mutiny of the Germanic auxiliary units against the legions of the Rhine army. The cause of the Varus Battle was therefore not a broad-based popular struggle, but an internal military revolt. The Roman Emperor Augustus kept this silent in order to divert attention from the fact that the rebellion came from among his own army. This would have called into question one of the basic pillars of military strategy , namely the use of larger Germanic auxiliary troops. This hypothesis caused heated discussion, especially outside of science, and meets with divided approval in today's history. They are supported by the fact that Augustus had recruiting difficulties after the Varus defeat. With his hypothesis that Arminius was merely the insidious, oath-breaking leader of a mutiny by Germanic auxiliaries, Timpe created a counterpoint to the conservative-pathetic-national history tradition, which Arminius viewed as the prudent leader of the Germanic freedom movement.

Reinhard Wolters strictly rejected the Timpe thesis, but he concludes that the Germanic contingents were claimed in greater numbers due to the recruitment difficulties. On the other hand, the thesis is supported by the excavations on the Kalkrieser Berg, in which no weapons or costume components of Germanic tribal warriors were found. Against Timpe's thesis, it was further argued that the title of a Roman knight was of no use for this thesis, since the careers of the leaders of the emerging regular auxiliary units were too different at this time and the title was not even the rule. In addition, not a single source mentions the rebellion of an auxiliary unit against the Legions of Varus, although this would have been a serious incident. The Göttingen ancient historian Gustav Adolf Lehmann objected to Timpe's formulation of "an internal military revolt" that the depictions of Cassius Dio and Tacitus expressly emphasize the anti-Roman uprising as a common cause of principes (tribal nobility) and plebs (people) of the Cheruscan tribe.

Furthermore, the interpretation of a passage in Velleius “adsiduus militiae nostrae prioris comes” is very controversial. Ernst Hohl translated it as “constant companion of my previous service”, while militia was previously understood as a “campaign”. Through this thesis, Hohl came to the conclusion that the Cheruscan as a knightly officer in Augustus' army had covered the same career as Velleius and at the same time with him. This would also fundamentally change the life of Arminius. According to Hohl's thesis, Arminius's life would look like this:

- 19 BC Chr. Birth.

- around 8 BC Admission to the prince's school on the Palatine Hill as a Roman hostage.

- around 1 BC Entry into the army as a Roman tribune.

- Participation in the Orient campaign of C. Caesar, where he acquired the name "the Armenians" (Armenius) (or his name was coined that way).

- 6 AD End of Roman career and return to the homeland of the Cherusci.

The majority of researchers, however, largely did not follow Hohl's thesis. It was argued against them, among other things, that the words adsiduus comes can only mean a “longer get-together”, which would significantly weaken Hohl's interpretation. Furthermore it was argued that the Velleiusstelle was not sustainable enough to draw far-reaching conclusions for the biography of Arminius. Nothing else is known about the alleged entry of Arminius into a Roman prince school.

Representations

Timpe's careful study of the sources has contributed to the fact that no national exuberance emerged during the Kalkriese excavations. Timpe's studies still lay the foundation for further current research on Arminius and the Roman-Germanic relations of his time.

In 1988 Barbara Patzek established the Varus Battle and the subsequent clashes between the Romans and the Teutons ethnographically . Some of the Germanic peoples found themselves in an externally imperceptible state of uncertainty due to their encounter with Roman culture. Through the upbringing of noble sons in Rome, including Arminius, the almost Roman Arminius gained the intellectual ability to reject Roman culture and to formulate and politically implement this discomfort of the Teutons towards Roman culture. Accordingly, Patzek interprets the Varus Battle and the further disputes not as a popular uprising of the Teutons, but as the result of a cultural movement.

In 1995, Alexander Demandt discussed aspects of constitutional law in the actions of Arminius. Demandt sees the story of Arminius as an important phase in the formation of the state. He describes the actions of Arminius as an approach to constitutional change, whereby a loosely arranged tribal being develops into a permanent dynastic tribal kingdom. However, neither Arminius nor any other West Germanic ruler succeeded in establishing a tribal kingdom. Demandt sees the reasons for this in the nobility, which on the one hand is a prerequisite for the formation of personal rule, but on the other hand hindered the consolidation of the monarchy - for example, Arminius was killed by relatives and the kingship of Marbod was overthrown. Demandt sees another cause in Rome itself: the empire generally supported kings when they accepted the Roman clientele , but strengthened the opposition to the nobility when they became too strong. Demandt relates his argument here to the economic and military strength that motivated the Teutons to defend themselves. This strength is reflected in the fact that Arminius went through the Roman military school and came into close contact with Roman culture.

swell

- Cassius Dio : Roman History . Translated by Otto Veh , Volume 3 (= Books 44–50) and 4 (= Books 51–60), Artemis-Verlag, Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-7608-3672-0 and, ISBN 3-7608-3673-9 , ( English translation by LacusCurtius ; Book 56 is particularly relevant for Arminius).

- Velleius Paterculus : Roman History. Historia Romana . Translated and published in Latin / German by Marion Giebel, Reclam, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-008566-7 , ( Latin text with English translation , position 2.118 is relevant for Arminius.)

- Tacitus : annals. Latin / German edited by Erich Heller, 5th edition. Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-7608-1645-2 , ( Latin text ; in the annals, for information about Arminius, the digits 1.55–68, 2.9–17, 2.44–46 and 2.88 relevant).

- Hans-Werner Goetz , Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Old Germania. Extracts from ancient sources about the Germanic peoples and their relationship to the Roman Empire . 2 parts, WBG, Darmstadt 1995, ISBN 3-534-05958-1 .

- Joachim Herrmann (Ed.): Greek and Latin sources on the early history of Central Europe up to the middle of the 1st millennium a. Z. Part 1: From Homer to Plutarch (8th century B.C. to 1st century C.E.). Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-05-000348-0 ; Part 3: From Tacitus to Ausonius (2nd to 4th centuries C.E.). Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-05-000571-8 .

- Lutz Walther (Ed.): Varus, Varus! Ancient texts on the battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Latin-Greek-German. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-018587-2 .

literature

The historical Arminius

- Frank Martin Beuttel : Germanic rulers. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-89678-603-6 , pp. 23-38.

- Heinrich Beck , Horst Callies , Hans Kuhn : Arminius. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 1, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1973, ISBN 3-11-004489-7 , pp. 417-421.

- Ernst Bickel : Arminius biography and Sagensigfried. Röhrscheid, Bonn 1949.

- Johannes Bühler: Arminius the Cheruscan. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 354 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Ernst Hohl : On the life story of the winner in the Teutoburg Forest. In: Historical magazine . 167: 457-475 (1943).

- Ralf G. Jahn : The Roman-Germanic War (9–16 AD). Dissertation, Bonn 2001.

- Harald von Petrikovits : Arminius. In: Bonner Jahrbücher . 166: 175-193 (1966). That. again in: Harald von Petrikovits: Contributions to Roman history and archeology. In: Bonner Jahrbücher - Beihefte 36 (1976), pp. 424–443.

- Erich Sander : To the Arminius biography. In: Gymnasium . No. 62, 1955, pp. 82-100.

- Michael Sommer : The Arminius Battle. Search for traces in the Teutoburg Forest (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 506). Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-50601-6 .

- Dieter Timpe : Arminius studies. Winter, Heidelberg 1970.

- Reinhard Wolters : The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57674-4 ; 1st, revised, updated and expanded edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-69995-5 .

Reception of the Arminius figure

- Michael Dallapiazza : Arminius. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 107-120.

- Volker Gallé (Ed.): Arminius and the Germans. Documentation of the conference on Arminius reception on August 1st, 2009 as part of the Nibelungen Festival in Worms. Worms Verlag, Worms 2011, ISBN 978-3-936118-76-6 .

- Otto Höfler : Siegfried, Arminius and the Nibelungenhort (= session reports of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna, Philosophical-Historical Class. Vol. 332). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1978, ISBN 3-7001-0234-8 .

- Otto Höfler: Siegfried, Arminius and the symbolism. Winter, Heidelberg 1961.

- Klaus Kösters : The Arminius Myth. The Varus Battle and its consequences. Aschendorff, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-00444-9 .

- Gerd Unverfetern: Arminius as a national leading figure. In: Ekkehard Mai, Stephan Waetzoldt (Hrsg.): Art administration, building and monument policy in the Empire (= art, culture and politics in the German Empire. Vol. 1). Mann, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-7861-1321-1 , pp. 315-340.

- Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf (ed.): Hermanns battles. On the literary history of a national myth. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2008, ISBN 3-89528-714-8 .

- Rainer Wiegels , Winfried Woesler (Hrsg.): Arminius and the Varus battle. History, myth, literature. 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Schöningh, Paderborn et al. 2003, ISBN 3-506-79751-4 .

- Martin M. Winkler : Arminius the liberator. Myth and ideology. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2016, ISBN 978-0-19-025291-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Arminius in the catalog of the German National Library

- Arminius / Varus. The Varus Battle in 9 AD - Information and resources on the Varus Battle and its reception in the Internet portal "Westphalian History" of the LWL Institute for Westphalian Regional History, Münster

- Novaesium alias Neuss - Arminius

- Historical novels about Arminius

- Small excerpt (pp. 78–104) from the dissertation “The Roman-Germanic War 9-16 AD” by Ralf G. Jahn

- New finds on the Harzhorn prove the presence of the Romans in the 3rd century AD.

Remarks

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2.88, 2.

- ^ Velleius 2, 118, 2.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 2, 10.

- ^ Velleius 2, 118.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 2, 10.

- ↑ Ernst Hohl: On the life story of the winner in the Teutoburg Forest. In: Historical magazine . Vol. 167, 1943, pp. 457-475, here: pp. 459ff.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Beck, Munich 2008, p. 97. See also: Peter Kehne: The historical Arminius ... and the Varus Battle from a Cheruscan perspective In: 2000 Years of the Varus Battle: Myth. Published by Landesverband Lippe, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 104–113, here: p. 105.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 56,19,2.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 56,18,5 ; 56,19,3 ; Velleius 2,118.4.

- ↑ Velleius 2,118,2ff. ; Cassius Dio 56,19,2-3. ; Florus 2,30,33; Tacitus: Annals 1,58,2.

- ↑ In addition Jörg Daumer: Uprising in Germania and Britannia. Unrest reflected in ancient evidence. Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 93 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Peter Kehne: Localization of the Varus Battle? A lot speaks against Mommsen - everything against Kalkriese. In: Lippe messages from history and regional studies. Vol. 78, 2009, pp. 135-180.

- ↑ Velleius 2, 117.1 .

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 1.61 .

- ↑ Theodor Mommsen: The locality of the Varus battle. In: Ders .: Collected writings. Volume IV, Berlin 1906 (first published in 1885: Die Örtlichkeit der Varusschlacht. Report of the meeting of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin, Berlin), pp. 200–246, here: p. 234.

- ^ Dieter Timpe: Arminius studies. Heidelberg 1970, p. 113.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 56,22,2a ; Velleius 2, 120.4 ; Tacitus: Annals 2.7 .

- ↑ Frontin: Strategemata 2,9,4.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Johne: The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006, p. 175.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2,9-10 .

- ^ So Herwig Wolfram: The Germanic peoples. Munich 1995, p. 39.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Varus, Arminius and Roman Germania. In: Ernst Baltrusch, Morten Hegewisch, Michael Meyer, Uwe Puschner and Christian Wendt (eds.): 2000 years of the Varus battle. History - archeology - legends. Berlin 2012, pp. 3–21, here: p. 14 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Dieter Timpe: Arminius studies. Heidelberg 1970, p. 114 f.

- ↑ Heinz Bellen: The Germanic bodyguard of the Roman emperors of the Julio-Claudian house. Mainz 1981, p. 41. The source: Tacitus: Annalen 1,24,2.

- ↑ See the different representations Velleius 2, 120–121 ; Suetonius: Tiberius 18-20 ; Cassius Dio 56.24.6 .

- ^ Suetonius: Augustus 23, 2.

- ↑ Velleius 2, 119, 5.

- ↑ Kurt Pastenaci: The Germanic Art of War. Karlsbad 1943, p. 200.

- ^ Ralf Günter Jahn: The Roman-Germanic War (9-16 AD). Dissertation, Bonn 2001, p. 117 f.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2 : 18-22 ; 1.55.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 1, 58, 6.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 11, 16.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 1, 63.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annalen 1, 63-69.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 2, 9-10.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 2, 16-26.

- ↑ On the political partisanship of the Germanic tribes cf. Ralf Günter Jahn: The Roman-Germanic War (9–16 AD). Dissertation, Bonn 2001, p. 117 f.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals 2, 46.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2.45.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2, 88.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2.88.

- ↑ Strabo 7,1,4.

- ↑ Velleius 2,118,1f.

- ↑ Florus 2,30,37.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2,88,3.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 1,59,3 .

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2,9,3.

- ↑ See Reinhard Wolters: The Romans in Germania. Munich 2004, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Änne Bäumer : Seneca's theory of aggression, its philosophical preliminary stages and its literary effects. Frankfurt / Main 1982, p. 77.

- ↑ Frank M.äbüttel: Germanic rulers. From Arminius to Theodoric. Darmstadt 2007, pp. 10, 25.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 56,19,2. ; Strabo 7, 1, 4 and more often, as well as in some places in the Tacitus manuscripts ( Annals 1,55 , 2,88 and 11,16 ).

- ↑ Velleius 2,118,2.

- ^ Harald von Petrikovitz: Arminius. In: Bonner Jahrbücher . Vol. 166 (1966), pp. 175–193, here: p. 177 ... a cognomen ex virtute would not have to be called Armenius , but Armeni (a) cus .

- ^ Klaus Bemmann: Arminius and the Germans. P. 104.

- ↑ Martin Luther: table speeches. 5.415.

- ↑ Michael Dallapiazza: Arminius. In: Peter von Möllendorff, Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music. Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, Col. 107–120, here: Col. 115.

- ^ Adolf Giesebrecht: About the origin of the Siegfried saga. In: Germania. 2, 1837, pp. 203ff. ( online ); also Otto Höfler: Siegfried, Arminius and the symbolism. Heidelberg 1961, p. 22ff.

- ^ Carl Courtin: Carl Ludwig Sands last days of life and execution. Frankenthal 1821, p. 21 (quoted from Ulrich Schulte-Wülwer: The Nibelungenlied in German art and art literature between 1806 and 1871. Phil. Diss. Kiel 1974, p. 74).

- ↑ Otto Höfler: Siegfried Arminius and the symbolism. With a historical appendix about the Varus Battle. Heidelberg 1961, pp. 60-64.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 2,88,3 ; Tacitus, Germania 2.2.

- ↑ Otto Höfler: Siegfried, Arminius and the symbolism. In: Wolfdietrich Rasch (ed.): Festschrift for Franz Rolf Schröder on his 65th birthday. Heidelberg 1959. pp. 11-121. Otto Höfler: Siegfried, Arminius and the Nibelungenhort. In: Meeting reports of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna, Philosophical-Historical Class, Vol. 332. Vienna 1978.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: The veil of memory. Principles of a historical memory. Munich 2004, pp. 255–289.

- ↑ Michael Dallapiazza: Arminius. In: Peter von Möllendorff, Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music. Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, Col. 107–120, here: Col. 110.

- ↑ Tacitus: Annals 2,88,2.

- ↑ Hans Gert Rolof: The Arminius of Ulrich von Hutten. In: Rainer Wiegels, Winfried Woesler (ed.): Arminius and the Varus Battle. Paderborn u. a. 1995, pp. 211-238.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Munich 2008, p. 180.

- ↑ Werner M. Doyé: Arminius. In: Etienne Francois, Hagen Schulze (ed.): German places of memory. Vol. 3. Munich 2001, pp. 587-602, here: p. 591.

- ↑ Quoted from: Henning Buck: The literary Arminius - Staging of a legendary figure. In: Wolfgang Schlüter (Ed.): Kalkriese - Romans in the Osnabrücker Land: Archaeological research on the Varus battle. Bramsche 1993, pp. 267-281, here p. 273.

- ^ Paola Barbon, Bodo Plachta: Arminius on the opera stage of the 18th century. In: Rainer Wiegels and Winfried Woesler (eds.) Arminius and the Varus Battle. History - Myth - Literature. 3rd updated and expanded edition, Paderborn 1995, pp. 265–290, here: p. 266.

- ^ Friedrich Ludwig Jahn: German Volksthum. Hildesheim-New York 1980 (reprint of the 1813 edition), pp. 349f., 359, 389f., 395.

- ^ Günther Jahn: Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, people's educator and champion for Germany's unification. Göttingen-Zurich 1992, p. 33.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Munich 2008, p. 186f.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters, The Romans in Germania. 5th, revised and updated edition. Munich 2006, p. 114.

- ↑ Cf. Gerd Unverfetern: Arminius as a national leading figure. Notes on the emergence and change of a symbol of the empire. In: Ekkehard Mai, Stephan Waetzoldt (Ed.): Art administration, building and monument policy in the Empire. Berlin 1981, pp. 315-340.

- ↑ Uwe Puschner: "Hermann, the first German" or: German prince with political mandate. The Arminius myth in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Ernst Baltrusch et al. (Ed.): 2000 years of the Varus battle. History - archeology - legends. Berlin et al. 2012, pp. 257–285, here: p. 261 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). Klaus von See : 'Hermann the Cheruscan' in German German ideology. In: Ders .: Texts and Theses. Disputes in German and Scandinavian history. Heidelberg 2003, pp. 63-100, here: p. 75.

- ↑ See the compilation of the determined Arminius operas in Paola Barbon, Bodo Plachta: Arminius on the opera stage of the 18th century. In: Rainer Wiegels and Winfried Woesler (eds.): Arminius and the Varus battle. History - Myth - Literature. 3rd updated and expanded edition, Paderborn 1995, pp. 265–290, here: pp. 289f.

- ↑ See the compilation of the determined Arminius operas in Paola Barbon, Bodo Plachta: Arminius on the opera stage of the 18th century. In: Rainer Wiegels and Winfried Woesler (eds.): Arminius and the Varus battle. History - Myth - Literature. 3rd updated and expanded edition, Paderborn 1995, pp. 265–290, here: p. 290.

- ↑ Hubert Schrade: The German National Monument . Munich 1934, p. 95.

- ^ Heinrich Heine: Germany. A winterstory. Cape. 11.

- ↑ For the inauguration ceremony see Charlotte Tacke: Monument in the social space. National symbols of Germany and France in the 19th century. Göttingen 1995, pp. 216-229.

- ↑ Uwe Puschner: "Hermann, the first German" or: German prince with political mandate. The Arminius myth in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Ernst Baltrusch, Morten Hegewisch, Michael Meyer, Uwe Puschner and Christian Wendt (eds.): 2000 years of the Varus battle. History - archeology - legends. Berlin et al. 2012, pp. 257–285, here: p. 267 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Monika Flacke: The foundation of the nation from the crisis. In: Myths of Nations: A European Panorama. Accompanying volume for the exhibition of the German Historical Museum from March 20, 1998 to June 9, 1998. Munich / Berlin 1998, pp. 101–128, here: pp. 101f.

- ↑ Felix Dahn: Armin the Cheruscan. Memories of the Varus Battle in 9 AD. Munich 1909, p. 45f. Quoted from Reinhard Wolters: The Romans in Germania. 4th, updated edition, Munich 2004, p. 115.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Munich 2008, p. 189f.

- ↑ Volker Losemann: Nationalistic interpretations of the Roman-Germanic conflict. In: Rainer Wiegels, Winfried Woesler (ed.): Arminius and the Varus Battle. History - Myth - Literature. Paderborn et al. 1995, pp. 419–432, here: p. 420. Uwe Puschner: “Hermann, the first German” or: Teutonic prince with political mandate. The Arminius myth in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Ernst Baltrusch, Morten Hegewisch, Michael Meyer, Uwe Puschner and Christian Wendt (eds.): 2000 years of the Varus battle. History - archeology - legends. Berlin et al. 2012, pp. 257–285, here: p. 270 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Charlotte Tacke: Monument in the social space. National symbols of Germany and France in the 19th century. Göttingen 1995, pp. 228-244. Dirk Mellies: Political celebrations at the Hermannsdenkmal after 1875. In: 2000 years of the Varus Battle. Myth (catalog for the exhibition of the Landschaftsverband Lippe in Detmold, May 16 - October 25, 2009). Stuttgart 2009, pp. 263-272, especially pp. 263-265.

- ↑ Werner M. Doyé: Arminius. In: Etienne Francois, Hagen Schulze (ed.): German places of memory. Vol. 3. Munich 2001, pp. 587-602, here: pp. 599f.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Munich 2008, p. 196.

- ^ Andreas Dörner: Political myth and political symbolism. The Hermann myth. On the emergence of national consciousness among Germans. Reinbek 1996, p. 230ff.

- ^ Andreas Dörner: Political myth and political symbolism. The Hermann myth. On the emergence of national consciousness among Germans. Reinbek 1996, p. 234f.

- ↑ Illustrated by Hans-Ulrich Thamer : Seduction and violence. Germany 1933–1945. Berlin 1994, p. 219.

- ↑ Volker Losemann: Nationalistic interpretations of the Roman-Germanic conflict. In: Rainer Wiegels, Winfried Woesler (ed.): Arminius and the Varus Battle. History - Myth - Literature. Paderborn u. a. 1995, pp. 419-432, here: pp. 424f. Werner M. Doyé: Arminius. In: Etienne Francois, Hagen Schulze (ed.): German places of memory. Vol. 3. Munich 2001, pp. 587-602, here: p. 600.

- ^ Klaus Bemmann: Arminius and the Germans. Essen 2002, p. 253.

- ↑ Herfried Münkler: The Germans and their myths. Berlin 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ Michael Dallapiazza: Arminius. In: Peter von Möllendorff, Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music. Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, Col. 107–120, here: Col. 115; Stefan Cramme: Historical novels about ancient Rome .

- ↑ Michael Dallapiazza: Arminius. In: Peter von Möllendorff, Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music. Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, Sp. 107–120, here: Sp. 118.

- ↑ Uwe Puschner: "Hermann, the first German" or: German prince with political mandate. The Arminius myth in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Ernst Baltrusch, Morten Hegewisch, Michael Meyer, Uwe Puschner and Christian Wendt (eds.): 2000 years of the Varus battle. History - archeology - legends. Berlin et al. 2012, pp. 257–285, here: p. 281 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Werner M. Doyé: Arminius. In: Etienne Francois, Hagen Schulze (ed.): German places of memory. Vol. 3. Munich 2001, pp. 587-602, here: p. 599.

- ↑ Volker Losemann: Nationalistic interpretations of the Roman-Germanic conflict. In: Rainer Wiegels and Winfried Woesler (eds.) Arminius and the Varus Battle. History - Myth - Literature. 3rd updated and expanded edition, Paderborn 1995, pp. 419–432, here: p. 432. Uwe Puschner: "Hermann, the first German" or: German prince with political mandate. The Arminius myth in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Ernst Baltrusch, Morten Hegewisch, Michael Meyer, Uwe Puschner and Christian Wendt (eds.): 2000 years of the Varus battle. History - archeology - legends. Berlin et al. 2012, pp. 257–285, here: p. 281 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Elmar Vieregge: 2000 Years of the Varus Battle - What significance does Arminius have for right-wing extremism? In: Martin HW Möllers, Robert Chr. Van Ooyen (ed.): Yearbook Public Safety 2010/2011 first half volume, Frankfurt 2011, pp. 165–172.

- ^ Dieter Timpe: Arminius studies. Heidelberg 1970. p. 49.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 56,23,1-3.

- ↑ Ernst Hohl: On the life story of the winner in the Teutoburg Forest. In: Historical magazine. Vol. 167 (1943), pp. 457-475, here: p. 474.

- ^ Reinhard Wolters: Roman conquest and rulership organization in Gaul and Germania. On the origin and significance of the so-called clientele-fringe states. Bochum 1990 ( Bochum historical studies. Old history , no. 8), p. 228.

- ↑ Jörg Daumer: Uprising in Germania and Britain: Unrest in the mirror of ancient evidence. Frankfurt / Main 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Reinhard Wolters: Roman conquest and rulership organization in Gaul and Germania. On the origin and significance of the so-called clientele-fringe states. Bochum 1990 ( Bochum historical studies. Old history. No. 8), p. 214.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 56,18,4.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annalen 1,55,2f.

- ^ Gustav Adolf Lehmann, The Varus catastrophe from the historian's point of view. In: Bendix Trier, Rudolf Aßkamp (eds.): 2000 years of Romans in Westphalia , Mainz 1989, pp. 85–98, here: p. 94.

- ↑ Velleius 2,118,2.

- ↑ Ernst Hohl: On the life story of the winner in the Teutoburg Forest. In: Historical magazine . Vol. 167 (1943), pp. 457-475, here: p. 458.

- ↑ Ernst Hohl: On the life story of the winner in the Teutoburg Forest. In: Historical magazine . Vol. 167 (1943), pp. 457-475, here: p. 465.

- ↑ Barbara Patzek: Understanding others in Tacitus' "Germania". In: Historical magazine. Vol. 247 (1988), pp. 27-51, here p. 46.

- ↑ Alexander Demandt: Arminius and the early Germanic state formation. In: Rainer Wiegels and Winfried Woesler (eds.): Arminius and the Varus battle. Paderborn u. a. 1995, pp. 185-196.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Arminius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Armenius; Armin; Irmin; Hermann |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Prince of the Cherusci, defeated the Romans in 9 AD |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 17 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | at 21 |