leader

The term leader is in German especially for Adolf Hitler as the absolute leader of the Nazi Party , and from 1933 as a dictator and later head of state of the German Empire in the era of National Socialism used. The terms leader party and leader cult were coined in analogy . Hitler was usually referred to as Der Fuehrer without giving his name by placing the definite article in front .

For the multiple use of the word leader in a different meaning, the use of more detailed compounds is often preferred (e.g. mountain guide , tourist guide , opposition leader , game leader ).

etymology

In antiquity it was a matter of course to designate a ruler as a "political leader", in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period , often using the Latin word dux ("leader") as an honorary title after the respective ruler's name, for example Robert, dux Francorum , i.e. " Robert, Leader of the Franks ”. A translation that does justice to premodern society is the German word Fürst ("der Erste", corresponding to Latin princeps ). In addition, the commanders-in-chief of armies were referred to as military leaders (lat. Dux belli “warlord”, mhd. Herrüerer ), which corresponds to the German duke from ahd. Herizogo “who goes before the army”.

According to Grimm, the root of the word (ahd. Fôrari ) is “verifiably only in the sense of worth carrier, load carrier , bajolus ” ( Latin ... carrier etc.), but only mhd. Füerære, vüerære, füerer, vüerer in the meaning of “one who leads"; it then expands in modern times to include today's meaning including "who leads an animal", in particular to " carter " and "who carries a weapon , an insignia " and the like.

Adolf Hitler

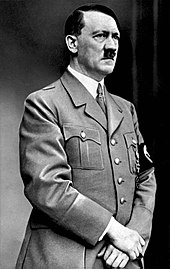

When he joined the German Workers' Party , which was soon to become the NSDAP , Hitler initially saw himself in 1919 as a “drummer”, not a “Führer”. He wanted to make propaganda for the strong man to come. After he replaced the party chairman Karl Harrer in 1920, but especially after the march on Rome of the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini in 1922, Hitler's self-image changed. He was now apostrophized by his followers as the “German Mussolini” and, in analogy to his title “Duce”, now also referred to himself as the leader of the NSDAP. According to Konrad Heiden , the term "Führer" was in common use in the NSDAP as a name and nickname for Hitler since 1925. The National Socialists and other right-wing radicals of the Weimar Republic rejected the term dictator for the undemocratic head of government they longed for, as it was rooted in “Romanic” instead of “Germanic” state thinking. In 1936, in a speech on the occasion of the occupation of the Rhineland , Hitler rejected the term dictator for himself: rather, he always felt himself to be a leader and thus a mandate of the German people.

Shortly before the death of Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , the Hitler government passed the law on the head of state of the German Reich on August 1, 1934 , according to which the offices of Reich President and Reich Chancellor would be combined when Hindenburg died by transferring the powers of the Reich President to the “Führer and Chancellor Adolf Hitler ”. When Hindenburg died a day later, it came into force. In a decree to Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick of August 2, 1934, Hitler determined “for all future” to be addressed only as “Führer and Reich Chancellor” in official and non-official dealings, because Hindenburg had given the title of Reich President “a unique meaning”.

Also on August 2, 1934, the soldiers of the Reichswehr were sworn in on Hitler as a person. This happened on the basis of a “ministerial ordinance ” by the Reichswehr Minister Werner von Blomberg without any agreement with the Reich government, including Hitler, and without the necessary legal requirement. The chief of the Wehrmacht Office , Major General Walter von Reichenau, formulated the formula in the Führer's oath . In the process of titling Hitler as "Leader of the German Empire and People", he deviated from the legally determined one. The referendum on the head of state of the German Reich announced in the decree of August 1, 1934, confirmed Hitler's decision on August 19, 1934. This then sanctioned Reichenau's name on August 20 in the "Law on the Swearing-in of Officials and Soldiers of the Wehrmacht" Signature as “Führer and Reich Chancellor”. From August 1934, Hitler held the title of Führer and Reich Chancellor ; In modifications, Hitler's self-chosen designation also found its way into prayers for worship services . The regional bishop of the Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union , Ludwig Müller , ordered in the Church Official Gazette in 1934 that an intercessory prayer be included “for the 'Führer and Reich Chancellor of the German People' Adolf Hitler”. Within the Wehrmacht, his address was "my leader".

An unprecedented Führer cult was cultivated around the charismatic Hitler during the Nazi era : streets were named after him, people cheered when they saw him at marches or other events, Hitler's pictures hung in offices and living rooms, and also in the regime's slogans - “One people, one Reich, one Führer”, “Führer commands, we follow!” - Hitler was present.

After 1934, the use of the term Führer for positions outside the NSDAP was restricted in public . The German Labor Front (DAF) was no longer subordinate to the “Führer of the DAF” but to the “staff leader of the DAF” and in the SA superiors should no longer be addressed as “my storm leader” but as “storm leader”. In January 1939, strict instructions were issued to the press that Hitler should no longer designate Fuehrer and Reich Chancellor , but only Fuehrer . In an instruction dated January 22, 1942, it was stated that in future the term Führer and Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht should “step into the background” in favor of the term “ Führer ”. The way was to be paved for the already widespread "reinterpretation of the official title of Führer into a proper name for Hitler".

The resolution of the Greater German Reichstag of April 26, 1942 ( RGBl. I p. 247) is seen as the conclusion of this development . There the rights claimed by the Führer are confirmed and the term “Führer” is used several times instead of “Führer and Reich Chancellor”, but not the name “Hitler”. In August 1942 the change of title also took place in the legislation. In his political testament of 1945 , Hitler wrote of his official seat as that of the "Führer and Chancellor" and signed as "Führer der Nation". Most of the time he was simply referred to as “Der Führer” or “Our Guide” for short ( see also: Führer Decree ).

Originally, the proto-fascist Austrian politician Georg von Schönerer allowed himself to be called a “Führer”. Many other high officials in National Socialist Germany also had the word Führer in their titles, such as the Reichsführer SS and the Reichsjugendführer , as well as the higher ranks of the SS . The basis of these designations was the leader principle and reference to medieval feudalist hierarchies presumably “primitive Germanic” origin ( feudal system ).

Use of language

In today's parlance, the use of the word Führer without further attributes or additions is mostly avoided in order not to make any reference to Hitler or National Socialism. It is often replaced by other words, such as Leiter , Chef or the English leader . Nevertheless, it is still customary in German to use -führer in compound words : party leaders are generally referred to as party leaders , the parliamentary group leader of the largest opposition party as opposition leader , and as the captain of a sports team, the word is still present, as is the police and military use ( police leader , Department leader , Hundertschaftsführer , platoon leader , group leader , squad leader ; but: leader ). In Italian usage , after the historical period of fascism, the English foreign word leader has largely replaced the original word duce today.

In this context, the German word Führer has found its way into other languages as a loan word . In the absence of umlauts in many character sets it is often written Fuehrer or Fuhrer , while Estonian (in which the letter ü exists) makes it for Fuehrer .

See also

- Outstanding leader of the People's Republic of China

- Leader of Iran

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Entry HEERführer, m. In: Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm: German Dictionary . Leipzig 1854–1960 (dwb.uni-trier.de)

- ↑ Entry FUHRER [furer], FÜHRER [fürer], m. In: Grimm: German Dictionary (dwb.uni-trier.de).

- ↑ entry GUIDE [Furer] m. In: Grimm: German Dictionary (dwb.uni-trier.de).

- ↑ Grimm: FÜHRER 4) and 6) .

- ↑ Frank Vollmer: The political culture of fascism. Places of totalitarian dictatorship in Italy , Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2007, p. 334 f.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw : Leader and Hitler Cult . In: Wolfgang Benz , Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Konrad Heiden: Adolf Hitler . Vol. 1: The Age of Irresponsibility. Zurich 1936, p. 216.

- ↑ Ernst Nolte : Dictatorship . In: Otto Brunner , Werner Conze and Reinhart Koselleck (eds.): Basic historical concepts . Historical lexicon on political-social language in Germany , Volume 1, Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1972, p. 922.

- ↑ Law on the Head of State of the German Reich of August 1, 1934 , in: documentArchiv.de, accessed on May 25, 2020.

- ^ Decree of the Reich Chancellor on the implementation of the law on the head of state of the German Reich of August 1, 1934 (Reichsgesetzbl. I p. 747) v. August 2, 1934, RGBl. I p. 751 . For this, Hitler pointed to "the size of the departed".

- ↑ Horst Mühleisen: Hindenburg's testament from May 11, 1934 . In: Karl Dietrich Bracher, Hans-Peter Schwarz, Horst Möller (Hrsg.): Quarterly books for contemporary history . 44th year, no. 3 . R. Oldenbourg Verlag, July 1996, ISSN 0042-5702 , p. 365 ( PDF [accessed February 1, 2016]).

- ↑ Klaus-Jürgen Müller : The Army and Hitler. Army and National Socialist regime 1933–1940 . DVA, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 978-3-421-01482-5 , p. 135 ff.

- ^ Karl Dietrich Bracher , Wolfgang Sauer , Gerhard Schulz : The National Socialist Seizure of Power. Studies on the establishment of the totalitarian system of rule in Germany in 1933/34 . Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 1960, ISBN 978-3-322-96071-9 , p. 354.

- ↑ Law on the swearing in of civil servants and soldiers of the Wehrmacht of August 20, 1934 , printed on verfassungen.de, accessed on May 25, 2020.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw: Leader and Hitler Cult . In: Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 28; Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society , Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914-1949 . CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 616; Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vocabulary of National Socialism. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-092864-8 , p. 241 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ In addition, Alfred Burgsmüller: The intercession for the state. On the problem of their implementation , in: Heinrich Riehm (ed.): Freude am Gottesdienst , Festschrift for Frieder Schulz, Heidelberg 1988, pp. 153–170, here pp. 160 f., Quotation p. 161.

- ↑ Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vocabulary of National Socialism . 2., through and revised Edition, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019549-1 , p. 244.

- ^ Quote from Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vocabulary of National Socialism . 2., through and revised Edition, Berlin 2007, p. 243 p. 243 (“my leader in the armed forces”).

- ↑ Cf. Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus , 2nd edition 2007, p. 243; Decision of April 26, 1942 .

- ↑ See RGBl. I, No. 91 of August 29, 1942 .

- ↑ GermanEnglishWords.com

- ^ DE Germany, l'Allemagne, Germany