Caspar David Friedrich

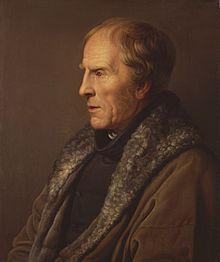

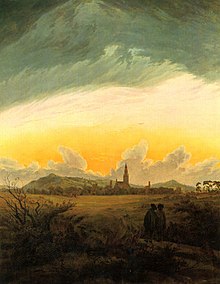

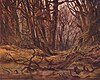

Caspar David Friedrich (born September 5, 1774 in Greifswald ; † May 7, 1840 in Dresden ) was a German painter , graphic artist and draftsman . Today he is considered the most important artist of early German Romanticism . He made an original contribution to modern art with his constructed picture inventions, which are geared towards the aesthetics of effect and which contradict the common notions of romantic painting as a soulful art of expression . In the main works of Friedrich the break with the traditions of landscape painting of Baroque and Classicism is carried out in a revolutionary way . The canon of themes and motifs in these pictures preferably combines landscape and religion into allegories of loneliness, death, ideas of the afterlife and hopes of salvation. Friedrich's image of the world and himself, which is characterized by melancholy , is seen as exemplary for the image of the artist in the Romantic era . With his works, the painter makes meaningful offers in largely unknown picture contexts, which include the viewer with his addressed emotional world in the process of interpretation. Since Frederick's rediscovery at the beginning of the 20th century, the open-mindedness of the images has led to a multitude of often fundamentally different interpretations as well as the formation of theories from an art, philosophical, literary, psychological or theological point of view.

Life

Origin and youth

Caspar David Friedrich was born in 1774 as the sixth of ten children of the tallow soap maker and tallow candle maker Adolph Gottlieb Friedrich and his wife, Sophie Dorothea, née Bechly, in the port city of Greifswald , which belongs to Swedish Pomerania . As a resident of a Swedish province that was also a German duchy, he did not have Swedish citizenship. Both parents came from the Mecklenburg town of Neubrandenburg and, like their ancestors, were craftsmen. There is no evidence according to which the families should come from a Silesian count dynasty or the Swedish nobility. It is possible that the relatives were embarrassed about the painter's origins, since "soap boiler" was a dirty word in Neubrandenburg that referred to a particularly cultured person.

Caspar David grew up in his parents' house in Greifswald at Langen Gasse 28. After the early death of his mother, his sister Dorothea was his substitute mother, the housekeeper "Mother Heiden" ran the household. The upbringing was the puritanical rigor of the father, who lived a Protestantism with a pietistic influence. There are contradicting statements about the economic situation of the family, which differ between daily misery and petty-bourgeois prosperity. The father was successful as a businessman in later years and in 1809 was able to save the lord of Breesen Adolf von Engel from bankruptcy with a substantial loan .

Nothing is known about Friedrich's attendance at school and the promotion of his artistic talent. From this time there are only sheets with calligraphic exercises of religious texts. Around 1790 he received a few hours a week from Greifswald university master builder and academic drawing teacher Johann Gottfried Quistorp a few hours of instruction in drawing from models and from nature as well as in the production of building plans and architectural drawings. Quistorp was also out and about in the Western Pomerania landscape with his students and was able to impart knowledge of baroque art of the 17th and 18th centuries with his extensive collection. He is said to have introduced Friedrich to the Ossian -influenced poetry of Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten .

According to tradition, a defining childhood experience was a fatal accident. While trying to save Caspar David, who fell into the water, his brother Christoffer drowned in 1787, who was one year younger than him. Carl Gustav Carus, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Wilhelmine Bardua and Count Athanasius von Raczynski reported in a dramatic way that Friedrich broke into the ice while skating. The painter's family only mentioned that the two boys had capsized on the moat in a small boat-like vehicle. A mild beginning of December 1787 speaks against the ice-cream variant. The woodcut Boy Sleeping on a Grave from 1801 is regarded as a processing of the death of his brother Christoffer. In Caspar David Friedrich's psychopathography , this event is named as a cause of later depression.

Studied in Copenhagen

In 1794 Friedrich began studying at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen , which at the time was considered one of the most liberal in Europe. During his training he copied drawings and prints under the supervision of Jørgen Dinesen, Ernst Heinrich Löffler and Carl David Probsthayn. After being transferred to the plaster class on January 2, 1796, drawing from casts of ancient sculptures was on the curriculum. From January 2, 1798, the teachers Andreas Weidenhaupt, Johannes Wiedewelt and Nicolai Abildgaard conveyed the work based on the living model . Influences in his artistic development are also attributed to Jens Juel and Erik Pauelsen . Painting was not a subject in Copenhagen. The Copenhagen painting collections with extensive holdings of Dutch painting served as illustrative material. As a rule, the professors paid little attention to the students.

The influence of the teachers on Friedrich is difficult to assess. The characters in his early theater pictures for Friedrich Schiller's drama The Robbers reveal an orientation towards Abildgaard. The portraits of the relatives created after graduation as well as the first attempts at etching are part of the technique of the Copenhagen education. Landscape drawings of the Copenhagen area were created outside of the curriculum. The theory of garden art of the Royal Danish Council of Justice, Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld , published in 1785 and popular in Copenhagen, had a profound effect on the representation of landscapes in the entire work .

From the perspective of the year 1830, the painter rebelled against the authority of his teachers.

“Not everything can be taught, not everything learned and achieved through mere dead practice; for what can actually be called a purely spiritual nature in art lies beyond the narrow limits of the craft. Therefore, you teachers of the art, who think so much with your knowledge and ability, take great care not to tyrannically burden everyone with your teachings and rules; because through this you can easily break the delicate flowers, destroy the temple of peculiarity, without which man can do nothing great. "

Friedrich had a larger group of college friends who were immortalized in his stud book. The friendship with the painter Johan Ludwig Gebhard Lund extended beyond his studies.

The early Dresden years

In the spring of 1798 Friedrich returned from Copenhagen to Greifswald and, presumably on the recommendation of the drawing teacher Quistorp, chose Dresden, a center of the arts, to live in Dresden that summer. Here teachers from the Dresden Academy such as Johann Christian Klengel , Adrian Zingg , Jakob Crescenz Seydelmann and Christian Gottfried Schulze influenced his artistic development. A considerable number of sketches and pictorial drawings were made in the vicinity of the city. A canon of motifs came together, which the painter would later use again and again. But he also copied landscapes by artists from the Dresden School and worked in the academy's act hall.

"The first two areas that I drew or began to draw were under all criticism, so I wanted to write to you I would be the worst of all draftsmen, but the page had changed and my third line did not turn out so bad, and which I started now doesn't seem to get so bad [...]. "

His preferred techniques were initially pen and ink drawings with ink and watercolors. From 1800 he earned his living with sepia leaves, as one of the first free artists who no longer received their commissions from the royal houses. The buyers were mainly in Dresden and Pomerania. The prospect of engagement as a drawing teacher with a Polish prince in 1800 did not materialize. From 1800 Friedrich dealt with the subject of death. He depicted his own funeral in the picture.

From Dresden he made long trips on foot to Neubrandenburg, Breesen, Greifswald and Rügen . Occasions were in October / November 1801 a. a. the double wedding of his brothers Johann Samuel in Warlin and Johann Christian Adolf in Woggersin and in June 1802 the wedding of Franz Christian Boll in Neubrandenburg. Longer stays can be proven in Breesen. In the village, the sister Catharina Dorothea Friedrich was married to the pastor August Jakob Friedrich Sponholz and Friedrich apparently thought he was in his surrogate family there. On these occasions numerous drawings of motifs of rural life and portraits of relatives were made.

In Greifswald there was an intensive preoccupation with the ruins of the Eldena monastery , a central motif of the entire work, as a symbol of decay, the nearness of death and the downfall of an old faith. In the summers of 1802 and 1803, the painter undertook extensive hikes on the island of Rügen with extensive artistic earnings. In July 1803 Friedrich moved into his summer apartment in Dresden- Loschwitz .

“You could call this period in Friedrich's painter's life the Rügen, so much and in many ways he portrayed the poetic character of the island (especially in sepia), yes, if Kosegarten is called the singer of Rügen, Friedrich could rightly be called the painter of Rügen. "

It is assumed that Friedrich got into a mental crisis with severe depressive periods after 1801, which is said to have led to a suicide attempt, which according to various statements may have occurred in 1801 or between 1803 and 1805. According to his contemporaries, the painter had been ill for a longer period in 1803/04 and his artistic production almost came to a standstill. The life crisis could have been exacerbated by an unhappy love affair, possibly with Julia Stoye, the sister-in-law of his brother Johann, whom Friedrich drew in a wedding dress in 1804.

Time of artistic success

Out of his obvious life crisis, Friedrich achieved his first significant artistic success in 1805. In 1805 he was awarded half of the Weimar Art Friends first prize. Although the two submitted landscapes, pilgrimage at sunset and autumn evening at the lake , did not meet the requirements of illustrating an ancient legend, Goethe ordered the award. The coveted prize included a presentation in an exhibition and a discussion by Heinrich Meyer in the Propylaea .

The first oil paintings were created in 1807, which expanded the creative possibilities compared to the Sepia. In Dresden there were friendships with the painter Gerhard von Kügelgen , the natural philosopher of Romanticism Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert and the painter Caroline Bardua .

In 1806, 1807, 1808, 1809, 1810 and 1811 Friedrich made trips to Neubrandenburg, Breesen, Greifswald, Rügen, Northern Bohemia, the Giant Mountains and the Harz Mountains. The breakthrough in oil technology was achieved with the Tetschen Altar in 1808, combined with a breach of conventions. In the Ramdohr dispute, critics and defenders of the cross in the mountains recognized the stylistic reorientation in the representation of landscapes and helped the painter to gain first fame.

The death of his sister Dorothea on December 22nd, 1808 and that of his father on November 6th, 1809 hit Friedrich hard. Apparently under this impression the pair of pictures The Monk by the Sea and Abbey in the Oak Forest was created . A euphoric discussion by Heinrich von Kleist on the occasion of the Berlin Academy exhibition in October 1810 immediately made the two paintings known to a wider audience. They were acquired by the Prussian king at the instigation of the 15-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia . Against the background of this reputation, the Berlin Academy elected the painter as a member on November 12, 1810.

Patriotism against Napoleon

After Napoleon's victory in the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt in 1806, Friedrich lived in Saxony, in a country allied with France. Dresden was the scene of warlike events several times, occupied by the French, Prussians and Russians. The painter lived in the Pirnaische Vorstadt in a house on today's Terrassenufer (at that time: On the Elbe ) in simple circumstances. He was a supporter of a national liberation movement and increased his national liberal sentiment to a chauvinistic hatred of the French, which he shared with like-minded people in Dresden, including Heinrich von Kleist , Ernst Moritz Arndt and Theodor Körner . His modest studio became a center for patriotic men. If Körner knew each other with songs and poems or Kleist with the Hermannsschlacht , Friedrich positioned himself with pictures such as tombs of old heroes or Chasseur in the forest . The painter felt too old to fight in the Liberation Army and avoided the chaos of war. For fear of contagious diseases, he settled in cribs in Saxon Switzerland for some time in 1813 . These circumstances repeatedly paralyzed his work. In 1813, Friedrich helped finance the equipment of his friend, the painter Georg Friedrich Kersting, for the service of the Lützow hunters , got into debt and wrote to his brother Heinrich:

“The cause of my present significant debt is 300 thalers. amount is not unknown to you; I do not regret it at all, on the contrary it serves to calm me down. "

As a result of the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna , Friedrich's native Greifswald, until then part of Swedish Pomerania , became the Prussian province of Pomerania in October 1815 . The introduction of the Swedish constitution in Pomerania was planned in 1806, but was not implemented because of the Napoleonic Wars and the deposition of the Swedish King Gustav IV Adolf (1809). Even afterwards, the painter felt a bond with Sweden, as suggested by a Swedish flag in the painting The Levels of Life .

Wedding, mourning, restoration

The painter's relationship to marriage was more objective. When he received a salary of 150 thalers as a member of the Dresden Academy from December 4, 1816, he wanted to afford a family, although Helene von Kügelgen, the wife of his friend Gerhard von Kügelgen, saw him as the "most unpaired of all unpaired couples" . On January 21, 1818 Caspar David Friedrich married Caroline Bommer , 19 years his junior , daughter of the blue dyer Christoph Bommer, in the Dresden Kreuzkirche . In the summer of 1818 the couple went on their honeymoon to Neubrandenburg, Greifswald and Rügen. In the marriage, three children grew up together: the two daughters Emma Johanna and Agnes Adelheid and the son Gustav Adolf, one child was stillborn. In 1820 the family moved into a larger apartment in Dresden on the Elbe 33. The professional situation also improved. Johan Christian Clausen Dahl , with whom Friedrich had a lifelong friendship, rented an apartment in the same house.

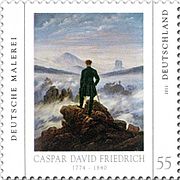

Franz Christian Boll died on February 12, 1818 in Neubrandenburg. Friedrich immediately designed a memorial for the pastor, which was executed by his friend, the sculptor Christian Gottlieb Kühn . This only realized monument based on the painter's drafts stands on the south side of the Neubrandenburg Marienkirche . In the years 1818 and 1819 a number of paintings were created that can be read as memorial pictures for Boll, such as the wanderer above the sea of fog or the gazebo . In 1818 the painter had found friends in Carl Gustav Carus and Christian Clausen Dahl who benefited from his artistic advice. A family friendship existed with the family of his friend Georg Friedrich Kersting, who was the painter head of the Royal Saxon Porcelain Manufactory in Meißen .

In 1820 his painter friend Gerhard von Kügelgen was killed by a robbery, the soldier Johann Gottfried Kaltofen. The loss hit Friedrich hard. The painting Kügelgen's grave was created in 1822 . Vasily Andreevich Schukowski's visit to the studio in 1821 turned out to be a stroke of luck . The Russian poet showed great interest in Friedrich's work and bought numerous sepias and paintings for his own collection and that of the Russian tsar. Zhukovsky's acquisitions secured a good part of Friedrich's economic existence for the next few years and made the painter known in Moscow and Petersburg artistic circles.

The political disappointments during the restoration , spying, intrigues at the academy and censorship embittered Friedrich. His art remained as a space in which he could express his political stance. The painting Hutten's grave is a clear confessional image in which he wrote names on the sarcophagus whose ideals he saw betrayed: Friedrich Ludwig Jahn , Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein , Ernst Moritz Arndt and Josef Görres .

“For some time now I have been feeling unwell, but my illness seems to be on the decline since yesterday. I have just wrapped myself in fur at the desk to talk to you loved ones today. I need to tell you, my brothers, from time to time how much I love you and how unlimited my trust in you is; the more I withdraw into myself through bitter experiences. But do not let the utterances arise in you worry because these are experiences that more or less every person has made when he has looked around the world for some time. "

On January 17, 1824, the painter was appointed associate professor at the Dresden Academy. However, he had hoped to be able to succeed the academy teacher Johann Christian Klengel , which probably failed because of his political attitude. Even if Friedrich could not teach at the academy, he taught students such as Wilhelm Bommer, Georg Heinrich Crola , Ernst Ferdinand Oehme , Carl Wilhelm Götzloff , Karl Wilhelm Lieber, August Heinrich , Albert Kirchner , Carl Blechen , Gustav Grunewald and for a while Robert Sorrow .

In the summer of 1826 the painter traveled to Rügen to take a cure in order to alleviate unspecified ailments. Hikes were only possible to a limited extent. This trip also alleviated his never-completely-gone homesickness, as he also used his Pomeranian pronunciation and spoke Pomeranian flat-bottomed with fellow countrymen . In the first exhibition of the Hamburger Kunstverein three of his works will be exhibited, including Das Eismeer . In 1828 Friedrich became a member of the newly founded Saxon Art Association . In May he took a cure in Teplitz (Bohemia).

Old age and illness

In 1830 a period of increasing artistic productivity began again, in which important paintings of high mastery such as The Great Enclosure or The Levels of Life were created . The attempt at technical and aesthetic innovation can be seen in the transparencies. But there was also an understanding of one's own positions in the art business with the art-theoretical fragments of utterance when viewing a collection of paintings by mostly still living and recently deceased artists . Friedrich documents his roots in early Romanticism and the rejection of the new realism in landscape painting, especially that of the Düsseldorf School . The later works stood outside the current art development, and received less and less attention from critics and the public. Selling the paintings had become difficult. The family lived in financial need.

On June 26, 1835, the painter suffered a stroke with symptoms of paralysis. He took a cure in Teplitz, which he could only afford by selling a few pictures about the poet Zhukovsky to the Russian Tsar's court.

“On the advice of the doctor, I stayed in Teplitz for almost 6 weeks for reasons known to you. I've been back since the day before yesterday. I'm pretty good on my feet now and hope that the after-effects of the bath will make my hand able to work again. The whole bathing time has been the most beautiful weather and the beautiful surroundings of Teplitz and the little that I can do because of the half-lame hand, can still be of use to me if otherwise I will ever regain the ability to grind. "

After the cure, Friedrich began to paint again, which gave him difficulties. Nevertheless, in 1835/36 the oil painting Seaside by Moonlight was still created . Mostly sepia drawings and watercolors, fewer landscapes and more allegories of death, were made by 1839. Friedrich sent some sepia drawings to the Dresden art exhibitions in 1836 and 1838.

In the last year of life, work came to a standstill. Carl Gustav Carus and Caroline Bardua took care of the friend. During a visit from Zhukovsky, the painter asked for financial support from the Russian tsar, but this did not arrive until after his death. Friedrich died at the age of 65 on May 7, 1840 in Dresden and was buried in the Trinitatisfriedhof .

family

parents

Adolph Gottlieb Friedrich (1730–1809) from Neubrandenburg, tallow candle maker and tallow soap boiler in Greifswald, married since January 14, 1765 to Sophie Dorothea Bechly (1747–1781), daughter of a tailor from Neubrandenburg

siblings

- Catharina Dorothea (born July 19, 1766 - † December 22, 1808). From December 1791 married to (August Jacob) Friedrich Sponholz (1762–1819), pastor in Breesen near Neubrandenburg . 12 children.

- Maria (Dorothea) (* April 5, 1768 - † May 27, 1791 with typhus). Married to Joachim Praefke (* 1773), businessman in Greifswald.

- (Johann Christian) Adolf (born March 10, 1770 - † June 23, 1838), businessman in Neubrandenburg. Since 1801 married to Margarethe (Friederika Magdalene) Brückner (1772–1820), daughter of the pastor and writer Ernst Theodor Johann Brückner from Groß Many. In the autumn of 1808 he took over his father's parent company in Greifswald, Lange Strasse 57, as a soap boiler.

- Johann David (March 27, 1772 - April 18, 1772)

- Johann Samuel (* May 18, 1773; † August 25, 1844), master of the blacksmiths and armories in Neubrandenburg. Married to Wilhelmina Stoy (* 1783) from Neubrandenburg since 1801. Caspar David Friedrich is registered as godfather of his son Caspar Heinrich, born in 1810.

- Johann Christoffer (* October 8, 1775 - † December 8, 1787). He drowned while saving his one year older brother Caspar David from drowning.

- (Johann) Heinrich (born January 19, 1777 - † February 28, 1844), light pourer and soap boiler in Greifswald. Until 1808 he managed his father's business. Married to Erdmute Amalie Henriette Hube (1791–1814) since 1809, two children. The son Karl Heinrich Wilhelm Friedrich (1811-1896) was the godchild of Caspar David Friedrich and visited his uncle during the stroke in June 1835.

- Christian (Joachim) (born February 22, 1779 - † May 8, 1843), cabinet maker and carpenter-altermann in Greifswald. He made printing blocks for Caspar David Friedrich. Married to Elisabeth Westphal (1795–1866) since 1813, 6 children. Caspar David Friedrich is registered as godfather of the daughter Marie Caroline Luise in 1814.

- Barbara Elisabeth Johanna (* June 7, 1780; † February 18, 1782 at the Blattern)

children

- Emma Johanna (born August 30, 1819 - † April 6, 1845), married in Dresden in 1838 to Johann Andreas Robert Krüger (1810–1862).

- In 1821 a stillborn child is recorded in the records of the Dresden Kreuzkirche .

- Agnes Adelheid (born September 2, 1823, † October 19, 1898), married in Dresden in 1846 to the husband of her late sister Johann Andreas Robert Krüger (1810–1862).

- Gustav Adolf (* December 23, 1824 - † January 4, 1889), married in Dresden in 1856 to Caroline Therese Lehmann (1828–1914). Son Harald was professor of painting at the Technical University of Hanover and the last direct descendant of Caspar David Friedrich.

Works

Friedrich's works include paintings, woodcuts, etchings, watercolors, transparencies, pictorial drawings, nature studies, drafts and drawing exercises. The number of paintings is estimated at 300, 60 of which were shown at the Dresden academy exhibitions, or 36 are still preserved in illustrations. A little over 1000 of an unknown number of drawings can be found in the catalog raisonné. Some of the work attributions are controversial. Most of the drawings belonged to around 20 sketchbooks that were no longer coherent, with the exception of the fully preserved Oslo sketchbook from 1807. Some of the known works were destroyed by the fire in the Munich Glass Palace in 1931, were lost in the bombing of Dresden in 1945 or are considered unexplained war losses .

painting

Working method of the painter

Friedrich used the format and aspect ratio of his pictures in terms of aesthetics and the theme. The size ranges from the miniature to the dimensions of 200 × 144 cm and is also assigned by the meaning of the motif.

“This picture is big, and yet you still want it bigger; because the sublimity in the conception of the object is felt to be great and still demands greater expansion in space. "

Regardless of the size, the pictures are very detailed and largely constructed in their structure. The lifelike reproduction of the individual picture objects has high priority. The painting style, which Friedrich appropriated around 1806 and never fundamentally changed, determined the overall concept of the picture from the start.

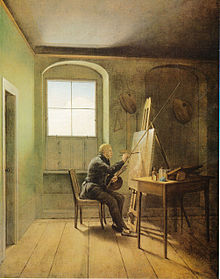

“He never made sketches, cardboard boxes or color sketches for his paintings, because he claimed (and certainly not entirely wrong) that these aids always cool the imagination. He did not start the picture until it was alive before his soul [...]. "

The preliminary drawing is carried out as precisely as possible on a fine, pre-primed canvas, accentuated with a thin brush or tube pen. Geometric figures were created using a ruler, square and tear bar. This is followed by a brown-tinted underpainting, on which a glaze-like color layer after layer of color is applied, thinning from top to bottom and coloring the signature structure with the local tone. In this way, paintings have a graphic character in the close up view of the details. The self-taught out of conviction developed this procedure from the sepia technique, which enables a shine through to the picture ground even with dark glazes. A different visual experience arises from a distance and at a short distance. The painter varied the application of paint over time. In the first oil paintings ( Sea Beach with Fisherman , 1807) the colors appear dry and almost monochrome. Later the colors were used lighter and also impasto ( Hünengrab in autumn , 1819). Often the foreground and background of a painting are treated differently. In his late work, Friedrich experimented with the new technique of transparent painting using translucent colors on paper. Contemporaries report on Friedrich's unusually spartan studio, in which only a few manual aids were available.

"Nothing is a minor matter in a picture, everything inevitably belongs to a whole, so it must not be neglected."

composition

Friedrich's principles of image composition are entirely at the service of aesthetic impact and image idea. In order to express perceptual contents like a parable, the painter used the means of construction and compilation as well as a whole reservoir of contrivances. He followed traditional landscape painting when a pictorial concept could be implemented, but broke with traditions when they narrowed him in this way and thus came to a picture conception that was revolutionary at the beginning of the 19th century. Even though the painter moved within a considerable range of design options, a clear canon of design principles can be recognized:

- Structured image order through symmetries, rows, parallel shifts, geometry of triangles, angles, hyperbola , diagonals, emphasis on vertical and horizontal

- Separation of foreground and background by a space barrier. (Wall of the garden terrace , gazebo )

- Confrontation of foreground and background through silhouetted surfaces, in the absence of a perspective axis leading into the depths ( The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog )

- Working with spatial layers as a means of distancing yourself from the subject

- Application of the golden ratio with the restriction that Friedrich did not know the name for the mathematical procedure because it was not coined until 1850.

Image and nature

In Friedrich's pictures, the bodies, things and appearances of nature are detached from their natural contexts, organized in the pictorial space and in variations led to ever new compositions. Drawings serve as preliminary work for a painting or as a template for the image form of the painting. Landscapes of different topographies are often put together on one picture surface. The painter also assembles architectures of various styles. For compositional reasons, he uses non-existent branches on trees from nature studies. Mountain ranges in the background of northern German landscapes are mostly placed for the purpose of background design. Flat landscapes are often modeled on, so that it is difficult to determine the real locations on which there is no doubt. Friedrich's paintings are hardly a simple imitation of nature, but rather emerged as a multi-layered process of a processed experience of nature and intellectual reflection. Despite the composition of landscapes, the painting gives the impression of great closeness to nature.

“Art acts as a mediator between nature and people. The archetype is too great for the crowd to grasp. "

Transparent painting

Around 1830 Friedrich discovered the transparent image that had been widespread in Europe since the 1780s . With this medium, pictures were painted and backlit in the dark on translucent materials. The Pomeranian compatriot Jacob Philipp Hackert has been considered the creator of a moonlight landscape created in this way since 1800.

At the suggestion of Wassili Andrejewitsch Schukowski , Friedrich made four transparent pictures for the young Russian heir to the throne Alexander . The painter planned a musical cycle that included a light installation and musical accompaniment. The motifs selected for the allegory of heavenly music are a fairytale incantation scene , lute player and guitarist in a Gothic ruin , the harp player at a church and the musician's dream . A moonlight landscape and the ruins of Oybin by moonlight were created based on Hackert's model . The mountainous river landscape can be viewed in a day and a night variant, depending on the lighting.

drawings

Friedrich's drawings are made with pencil, pen and ink and are mainly found in sketchbooks. He showed a special talent in using the pencil, just invented by Nicolas-Jacques Conté , in several degrees of hardness. With a very differentiated interior drawing, his drawings even acquire a painterly quality. The painter's primary interest was nature motifs. In the Dresden area, on trips to Mecklenburg, Pomerania, the Harz Mountains or the Giant Mountains, depictions of plants, trees, rocks, clouds, village views, ruins, coastal and mountain landscapes were created. The course of Friedrich's wanderings can be reconstructed from the sketches. The drawings served as the basis for elements of paintings, sepias and watercolors, but in their mixture of care and liveliness they have an artistic intrinsic value.

Because of his low talent in figure drawing, figure representations and portraits only make up a small part of the overall work. It is rumored that Georg Friedrich Kersting executed the figures in Friedrich's paintings in some cases. There are some traced figure drawings that have been preserved, which were helpful for the figure representations in the oil paintings, for example the Two Seated Women (1818) used in the painting Resting at the Hay Harvest (1815). For the study of Hutten's grave , August Milarch was very likely put on paper using a camera obscura .

Sepia and watercolors

Friedrich achieved a high level of mastery in his sepia early on. With the Rügen landscapes such as the view of Arkona (1803), he earned a lot of applause from the public and from the reviewers and thus had a considerable share in the enthusiasm for Rügen that began around 1800 and the initial Rügentourism. With sepia painting, which enjoyed great popularity, the painter was able to achieve delicate tonal gradations and fine color transitions, and was also able to capture observed light phenomena in nature.

The watercolor is also represented in the entire artistic work. The first works in this technique were created during the time at the academy, but large formats from 1810 and masterful pieces only in later work. In addition to the watercolor studies, there is a whole series of pictorial watercolors. From 1817 the watercolors are combined with pen drawings.

Groups of works according to themes and motifs

Portraits

Friedrich did not want to be a portrait painter himself and thus assessed his artistic talent in this area realistically. Thus, the portraits from his hand are limited to self-portraits or depictions of relatives and friends. Most of these portraits are drawings and were created in the period after the Copenhagen Academy in 1798. In formal terms, these drawings are in the tradition of conventional portrait art. One can see the painter's effort to capture the greatest possible individuality of what is depicted. In relation to the nature studies, the number of portraits remains negligible.

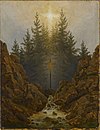

Manifest images

In quick succession he created paintings between 1808 and 1810 that can be described as program or manifest images. This period was the painter's most productive. The Tetschen Altar is the most complex picture with which the programmatic step from the empirical landscape to the landscape icon took place. Friedrich iconized the experience of nature and broke with the traditions of landscape painting. The previous relationship between art and religion was also called into question. The cross in the mountains eludes the genre definition and takes a new place between landscape and sacred image. The Ramdohr dispute sparked a heated debate about a work of art that was hitherto unknown in Germany.

The following pair of images, The Monk by the Sea and the Abbey in the Oak Forest, was not the subject of public controversy, although it received an unusually high level of attention due to Heinrich von Kleist's discussion. The exhibition of the two paintings in Berlin in 1810 and the purchase by the Prussian royal family brought the breakthrough to success. Together with the monk and the abbey, the painter invented those structures in the composition that the French sculptor Pierre Jean David d'Angers described as "tragédie du paysage", the tragedy of the landscape. The formal basic motifs of horizontal layers and vertical axes communicate alienation and rapture, trigger deep feelings in the viewer and make the religious picture narration tangible. Both paintings are key images for Friedrich's landscape painting and the result of a consolidation of the pictorial language in a further development of the award-winning Weimar Sepia from 1805.

Patriotic pictures

Friedrich confessed to using the means of art to express his anti-feudal, national and anti-French attitude and to pay tribute to the heroes of the wars of liberation against Napoleon. He combined the hoped-for social changes with religious renewal. From 1811 the painter was looking for suitable allegories and metaphors with which his messages could be conceptually implemented. The paintings Winter Landscape and Winter Landscape with Church can be seen as the first two pictures with such a political message, describing hopelessness and liberation from it. With the tombs of old heroes , a landscape of monuments was created in 1812, in which the reference to the German national symbol Arminius and the visible French chasseurs can be assumed to be an unencrypted image statement. The idea of confronting the French with their military downfall at the coffin was further developed in the painting Cave with Tomb in 1813/14 . In 1813, the Chasseur in the forest only describes the decline of the Napoleonic army. From 1815 onwards, people are shown wearing old German costumes, which at that time were regarded as a commitment to the German national feeling and were banned in 1819 with the Karlovy Vary resolutions and the persecution of demagogues . The painter is said to have commented on the painting Two men contemplating the moon from 1819 with the words "They are doing demagogic activities". Hutten's grave openly laments the betrayal of the ideals of the wars of liberation in the political restoration in 1823/24 .

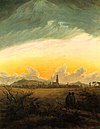

City images

Friedrich discovered around 1811, with the painting Port of Greifswald by moonlight, city views as a motif, which can then be found in the later work. In these city images, the city silhouettes have different functions in the picture narration. Views emerged from the biographical locations that apparently reveal an inner relationship between the painter and the respective city. The representations of Greifswald show a vedute-like clarity. Neubrandenburg appears transfigured or burning. Dresden is preferably placed behind a hill or a wooden fence in the picture compositions. Usually one can assume that these pictures are true to nature.

A second group of pictures shows dreamy fantasy cities in the deep space, as in the paintings Gedächtnisbild für Johann Emanuel Bremer or Auf dem Segler . A third group places the pictorial personnel in the foreground in a symbolic relationship to a city in the background, as in the painting The Sisters on the Söller at the harbor . In this case, identifiable picture elements can be used to assign a real city.

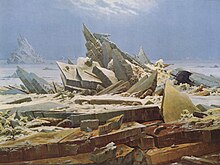

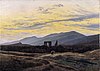

Distant subjects

With the Eismeer , the Watzmann and the Junotempel in Agrigento , Friedrich created a group of paintings whose motifs he did not get to know personally in nature - the North Sea, the Alps and Sicily. The three pictures were taken between 1824 and 1828 with a narrow date in a biographical window.

During this period, a change in motif can be registered in the work. Although the painter was always a master of compilation and construction, in this series he once again achieved an increase in landscape painting beyond the naturalism of mere observation of nature to visionary pictorial inventions. He also breaks completely with the staffage-oriented manner of representation and shows pictorial spaces with intentional emptiness. The message of the impressive pictures is encrypted and can be interpreted accordingly. For the Italian riders among his artist colleagues, Friedrich remained a mystery.

“Caspar David Friedrich ties us to an abstract thought, uses the natural forms only allegorically, as symbols and hieroglyphs, they should mean this and that: in nature, however, every thing speaks for itself, its spirit, its language lies in everyone Shape and color. "

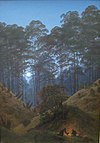

Back figure

Caspar David Friedrich developed the back figure as the central theme of landscape painting. The romantic painter went beyond their traditional function as a yardstick, compositional element or teaching guide. For him, the figure on the back essentially determines the shape and symbolism of his paintings, watercolors and cuttlefish. It is less about depictions of nature than about constructive compositions with theatrical features. The painter thus makes a largely open-minded offer of contemplation for the viewer. Usually it is figures isolated in the landscape, individually or in small groups, who hold a dialogue with nature without any action. In this relationship between man and nature, in the most common interpretation, the divine universe appears in its transcendental infinity, to which Friedrich gives an aperspective and immeasurable spatial quality.

Garden landscapes

Friedrich's visual aesthetic is strongly influenced by the English landscape garden . Not only the motifs of famous landscape gardens from the Copenhagen student days (Luisenquelle in Fredriksdahl) and from the first years in Dresden testify to this . It is also the views and rules of garden art that have been transferred to landscape painting and that can be seen as a stimulus for image structure and composition for some of the landscapes. Willi Geismeier , Hilmar Frank and Helmut Börsch-Supan referred to the landscape garden as a prerequisite for Friedrich's work in the history of ideas and named the theory of garden art by Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld as the source . Above all, it is the ideas of the Kiel professor of philosophy and the fine arts about composing moods by bringing together the various landscape elements that the painter used for his work. The Sepia Ideal Mountain Landscape with Waterfall , dated around 1793, can be considered the earliest example of this. Other works from this context are The Evening , The Great Enclosure , the Eldena ruins in the Giant Mountains , the Juno temple in Agrigento , the tombs of old heroes or the Giant Mountains landscape .

Gothic

In Friedrich's pictorial allegories, Gothic architecture is perhaps the most unambiguous symbol and appears intact in his work, as a ruin or a capriccio. With the ruins of Eldena Monastery , first drawn in 1801 and repeatedly used in sepia and paintings, the turn to Gothic begins. The painter found himself in harmony with the zeitgeist, which romanticized the German Middle Ages as the ideal age. The Gothic was rediscovered as an architectural style and felt as a German style in contrast to Baroque and Classicism, close to nature and like the expression of the divine in church construction. The master builder Karl Friedrich Schinkel addresses the ideal of the Gothic city in his paintings almost at the same time.

Friedrich took the Gothic churches of Greifswald, Stralsund and Neubrandenburg in the picture. But he also composed fantasy architectures from elements of real church buildings ( The Cathedral , 1818) or symbolically combined Gothic architecture and nature ( Cross in the Mountains , 1818). He also decidedly combined the Gothic with a vision of a religious renewal of the Christian church ( Vision of the Christian Church , 1812). In Pomerania the painter was regarded as a specialist in Gothic and in 1817 was commissioned to design the new interior fittings and the liturgical equipment of St. Mary's Church in Stralsund . Just like the church buildings in his paintings, the style of these designs is neo-Gothic.

Image pairs and cycles

In the complete works one finds a multitude of picture pairs and picture cycles, beginning 1803 up to the year 1834. The counterparts can be antithetically related pairs of opposites, the cycles, mostly in four parts, refer to the seasons, times of day or age. Functionally, the pairs of paintings and graphic counterparts make it possible, in addition to the allegory, to make clear a temporal dimension of what is depicted or different historical levels, which is seldom achieved in just one pictorial space as in the stages of life . The antitheses are motif, thematic or topographical. By juxtaposing summer (1807) and winter (1808), Friedrich follows a long tradition of painting. The heavenly abundance of nature and human existence is juxtaposed with the desolation of a ruin in winter with a lonely monk.

Different pairs of images can also be connected to one another in a motif development. An example of this is the intellectual and formal continuation of the Weimar Sepia (1805) via the sea beach with fishermen and fog (1807) to the monk by the sea and the abbey in the oak forest (1809). A technically created pair of images is the transparent painting Mountainous River Landscape (around 1830–35), in which the different landscape views are created by varying the lighting of the image. In 1803 Friedrich began his first cycle in sepia: spring, summer, autumn and winter, in which the seasons are represented with the times of life. A similar series is dated 1808. In the 1820s, the life cycle was already in seven parts. In addition to the simple landscapes of the paintings of the time of day cycle from 1820, there are also seascapes. The painting Der Abend , which was created from Hirschfeld's descriptions of the times of day and an evening painting by Claude Lorrain , shows how the painter ties in with traditions of the 18th century .

"One word gives the other, as the saying goes, one story gives the other and so too a picture gives the other."

Designs for monuments and architecture

Friedrich designed a number of memorials and grave monuments. The sculptural-architectural work, however, only makes up an insignificant part of the work. Of 33 design drawings, only eight were carried out. A group of these designs are apparently monuments to the heroes of the Wars of Liberation. One drawing for a grave memorial with the inscription Theodor could be intended for Theodor Körner, who fell in 1813, while the painter dedicated another to the Prussian Queen Luise, who died in 1810 . There were no clients for that, just as little for a monument to Gerhard von Scharnhorst that he had in mind. Around 1800 it was quite common to design monuments in honor of the new bourgeois heroes or poets, as a recommendation in the literature for the design of landscape gardens. In the Romantic era, the monuments that had previously had their place in the gardens of the princes were civicized and placed in the urban areas. Another group is made up of smaller tombs for tombs in Dresden cemeteries, which can be viewed as less ambitious contract work. The only monument that was executed is the one for the pastor of the Neubrandenburg Marienkirche Franz Christian Boll, who died in 1818 .

In a large number of his works, Friedrich's painting is shaped by an architectural way of thinking, so the preoccupation with architectural drafts that go beyond the tectonics of the monuments is obvious. In 1817 the painter was commissioned to design the interior of Stralsund's Marienkirche , which was destroyed during the French occupation of the city. Up to the summer of 1818, neo-Gothic drafts for the choir, altar, pulpit, candlestick, Fial tower, measuring device, church stalls and baptism were made, the formal language of which was based on the memorial drafts. The plans were probably not carried out for lack of money. There are other altar designs in a different style and without a known destination. One design is based on the symbolism of the Tetschen Altar. Draft drawings for a small neo-Gothic church with classicist elements, including furnishings, are also dated around 1818. Gerhard Eimer points to similarities with the church in Dannenwalde built in 1821 .

Fonts and texts

Art theory

Friedrich wrote works on art theory that provide information on his reflections on his own art and on contemporary art development. Art theoretical submissions from 1829 to 1831 with the title utterances when viewing a collection of paintings by mostly still living and recently deceased artists . There are 165 undated and disordered texts of various lengths with a total of 3215 lines of notes. The works and artist names referred to are encoded with letter sequences. With knowledge of the Dresden art scene and the development of art in Europe of those years, one can interpret the statements with great certainty. The majority of the texts reveal Friedrich's displeasure with the Dresden Academy and its encrusted structures as well as his own bitterness at not being in demand in the art world. Against the risk of art flattening through adaptation to the tastes of a broad public, the painter formulated his principles and convictions that were rooted in early Romanticism.

“The only true source is our heart, the language of the pure childlike mind. A structure that does not spring from this source can only be artificiality. Every real work of art is received in a consecrated hour and born happier, often unconsciously to the artist from an inner urge of the heart. "

As early as 1809, under the heading On Art and Artistic Spirit, Friedrich noted demands on the artist in ten commandments, which in essence can be interpreted as the mental preliminary stage to the "utterances". These texts are formally based on the Ten Commandments of Moses .

"You should obey God more than people [...] So if you want to devote yourself to art, do you feel your calling to dedicate your life to it, oh, pay close attention to the voice of your inner being, because it is art in us."

Poems

Given Friedrich's low affinity for writing, it is surprising that the painter left behind some poems, songs, prayers and aphorisms. The texts deal mainly with religious topics, have a confessional character and are used in the interpretation of the work, for example to assess the often-occurring allegories of death.

In a short poem, Friedrich commented on his choice of motif:

- Why the question has often come to me

- You choose the subject of the painting

- So often death, impermanence and grave?

- To live forever

- one must often submit to death.

A similar aphoristic poem:

- You call me misanthropist

- Because I avoid company.

- You are wrong

- I love her.

- But so as not to hate people

- I have to refrain from dealing with it.

Letters

Friedrich's hand has published 105 letters from the period 1800 to 1836. One can assume that considerably more exist or have existed. The texts are addressed to relatives, friends and famous contemporaries such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. They document the way of life, illness and artistic development or contain comments on some paintings such as the Tetschen Altar , and are therefore an important source for the interpretation of the work.

interpretation

The interpretations of Friedrich's work, which mostly refer to the most important of his works, are multifaceted and often differ fundamentally in their theoretical approaches. The tendency of this art to be open to meaning as well as the contradictory statements and confessions of the painter offer a lot of leeway in the interpretation. Basic patterns of interpretation can be recognized to which the different theories can be assigned in terms of their substance:

- Generation of meaning to the images from biography and work process

- Applying the theory of the sublime and sublime to large parts of the work

- Reference to a presumed consistent system of religious symbolism and allegories

- superficial classification of art in a contemporary historical and political context

- Assessment of the works of art from a nature-mystical-early romantic point of view

- Assumption of a metaphysical-transcendent tendency

- mystical geometry as the basic structure of the image composition

- Understanding biography and work through psychoanalysis

- Friedrich seen as a painting Freemason

As with hardly any other artist, the scientific discourse on different positions is irreconcilably led. The danger is recognized of using Friedrich's art as a mass of discourse or of cutting down the painter in order to incorporate him into his own worldview. The ever more intensive art historical, biographical and philosophical examination of Friedrich's pictorial thinking has made the view of the work more complicated, ramified, detailed and difficult.

Nature and religion

It is evident that Friedrich represents his art from a religious point of view. His Protestant-Pietist upbringing shaped him. With a Christocentric faith, he understood in his work the representation of nature as a constant worship service, saw God in everything, even in the grain of sand. The religious interpretation of the work derives from this attitude of the painter Christian pictorial statements and pictorial narratives even where the picture content does not seem to suggest a sacralization of the landscape. Carl Gustav Carus introduced the term pantheism or entheism for Friedrich's relationship to nature, which was taken up early in research. In addition to the pantheistic worldview, the Lutheran theology of the cross is accepted as the second important component in the painter's religious aesthetic. With the catalog raisonné, Helmut Börsch-Supan provided a consistently religious interpretation and thus had a lasting impact on the perspective on the oeuvre. A consistent system of symbols with Christian connotations is assumed, dying trees or poplars are symbols of death, spruces are the hope of eternal life, bridges are the transition to the world beyond, fences separate paradise from earthly existence, the rock is a symbol of faith, oaks embody a pagan view of life etc. The importance of these elements in the composition of the picture determines the tendency towards hope or hopelessness. Even where the contemporary historical statement is undisputed, as in the painting tombs of old heroes , political and Christian allegory mix, the resin cave alludes to the grave of Christ and the spring-like vegetation to a spring theme. Theology and thus the question of which theological teachings may have been the inspiration for the development of the pictorial ideas occupies a large space in religious interpretation. This influence is derived from the biographical proximity of contemporary theologians. Börsch-Supan refers to Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten, who is known on the island of Rügen for his sermons in the great outdoors . Werner Busch sees Friedrich Schleiermacher's ideas as the key to Friedrich's understanding of the picture. Willi Geismeier clearly notices in Friedrich the attitude of the revival Christianity that developed at the beginning of the 19th century .

Political Confessions

In the reception of the 20th century, Friedrich's pictures have only been regarded as open political confessions since the eve of the First World War. Ever since Andreas Aubert propagated some landscapes as the embodiment of the patriotic spirit, these have acquired national symbolic value. This judgment related to the paintings Gravestones of Old Heroes , Felsental (The Grave of Arminius) and The Chasseur in the Forest . Also Jost Hermand sees the images of death and resurrection mood 1806-1809 marked by Germanic-Christian "sentiments symbols" that are built against the "Welsh Antichrist" Napoleon. The encryption is due to the fact that images with an openly democratic or nationalist content had no chance of passing through princely or French censorship. Most contemporaries should have understood, however, that the works of the years 1806–1813 evoked the “Germanic, Nordic, Osian, medieval, Gothic, Dürer period, Huttensche and Lutheran” of a Germany that was currently in ruins, but one day from ruins to the new Life grow up. Whether the “grave of Christ or the megalithic grave, the cross on Golgotha or the Iron Cross, the pillars and cross ribs of Gothic churches or the trunks of German oaks” - the symbolism that appears most clearly in the Tetschen altar reflects the “German” longing to infinity and a closeness to nature that is opposed to Romanesque classicism. The painter's statements in letters provide evidence of a clear anti-French stance during the time of the Napoleonic occupation of Europe, increased to a chauvinistic hatred of the French and anti-feudal attitudes, as far as the bourgeois monuments are concerned. For him, Arminius and the Prussian army reformer Scharnhorst were symbolic figures of the struggle against "royal servants". In 1813 he signed a spruce study: "Prepare yourselves for a new fight today, German men, salvation your weapons." One can also assume that images of the theme of the renewal of the Church, especially Protestantism, mean more civil liberties and political renewal . The idealization of the Gothic cathedral as a German style combines political and religious statements as an artistic statement.

Friedrich's patriotism is hardly doubted. The description of his political stance and its consideration in the interpretation of the work are, however, mostly overambitious with the rather discrete references available and should be read in the contemporary historical context of the interpretation. In the exuberance of the victory over Napoleon in 1814, the painter's rocky landscapes were also interpreted as “patriotic”, with an effect that has continued to be received today. In the Federal Republic, in the wake of the sixty-eight movement and its anti-national stance in the assessment of Friedrich's patriotic pictures, the painter's “Germanness” and “his relationships with the new German zealots like Ernst Moritz Arndt [...] and the original gymnastics father Friedrich Ludwig Jahn” moved forward. in the foreground. According to Jens Christian Jensen, the advocacy of the German cause in the fight against Napoleon contributed to the narrowing of his artistic horizons. However, in view of the princely and French censorship before 1813 (and after 1815), there were no exhibition opportunities for pictures with undisguised national or democratic themes. According to his own admission, the painter avoided the pointed political allegory. Figures in old German costumes are considered a subliminal patriotic creed. The painting Hutten's grave from 1823 shows little encryption. Here, the betrayal of the ideals of the Wars of Liberation during the Restoration period is clearly deplored.

“Dear good brother! The evening before yesterday I received your letter and when I left LYON printed on the label and recognized your hand, my heart rumbled and so as not to spoil the night I left your letter yesterday. You yourself feel that it is not right that you are in France as a German, and that still comforts me to some extent; because otherwise I would completely doubt your Germanness. Meanwhile I resent it so much, dear good boy, that I have to ask you not to write to me as long as you are in France. "

Masonic image program

According to Hubertus Gaßner , the hidden geometry in Friedrich's pictures and the metaphorical language used refer to the distinctive symbolism of the Freemasons at the beginning of the 19th century. For example, the back figures placed in the landscape or ships entering and leaving are also basic figures of Masonic thought. Anna Mika also analyzes the pictures from the point of view of hidden geometric figures from the Masonic initiation program and clearly recognizes the “seven-step ladder to heaven” in the hiker above the sea of fog . It is assumed that Friedrich was a Freemason himself. However, there is no evidence of this. The painter is not listed as a member of either a Greifswald or Dresden lodge, but he had close ties to Freemasons. His drawing teacher Quistorp belonged to the Greifswald Johannesloge Carl to the three griffins , Kersting to the Dresden Lodge Phoebus Appollo . The altar design, cross with rainbow, from 1816, which looks similar to the Tetschen altar, is said to have been made by Friedrich with pronounced Freemason symbolism in memory of the deceased Duke Karl.

Mystical geometry

Werner Sumowski describes a multi-stage process of image creation in Friedrich, which begins with an abstract composition of lines and surface elements and thus follows a romantic doctrine of mystical geometry, which is covered by the landscape motifs and becomes the inner form of the image. This creates a structure between naturalness and distance from nature. The reference to romantic mathematics goes back above all to Novalis, who stated “Geometry is the transcendental art of drawing” or “Pure mathematics is religion”. Schelling , Schubert , Steffens , Oken wanted to recognize God in the geometric figure. Werner Busch sees the use of the hyperbolic scheme in works such as Der Mönch am Meer or Abtei im Eichwald , in which the hyperbola that opens upwards is inscribed in the sky and is considered a metaphor for the anticipated infinity.

Theory of the sublime

Friedrich's work has been associated with the philosophical theories of the sublime since the 1970s . In addition to art scholars, philosophers and Germanists also take part in this discourse of sublimity, referring to theories of Edmund Burke , Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller . The numerous publications on the topic can be characterized in a few exemplary positions:

- Friedrich's staffage figures, which stand in front of nature, are attributed Kantian moral sovereignty and sublime feelings, for example, by Barbara Ränsch-Trill. Then illustrate the distance to nature the reflection of the subject. When it comes to the association of the infinite, such as the wanderer above the sea of fog, Kant's statement about the mathematically sublime is used.

- Werner Hofmann sees Friedrich's other ego in the Mönch am Meer exposed to the dangers of nature, so that the sublime is not produced as a physical threat, but as an object of imagination. This coincides with Schiller's thesis of the connection of two contradicting sensations in a single feeling, which proves our moral independence.

- According to Johannes Grave , Friedrich was a critic of Schiller's theory of the sublime. The example of the painting Das Eismeer shows the questioning of the viewer's position, a loss of security as well as irritation and alienation - all of this makes a sublime feeling no longer possible.

- Nina Hinrichs formulates the counter-thesis to the reference to sublimity, Friedrich's pictures refer to a religiously connoted contemplation of nature and not to the degradation of nature as an object for the spiritual elevation of man through his reason. In the reception of the 19th century, the painter's pictures were marked as “sublime”, but the term was not used in the philosophical but in the general sense. In Romanticism the moral evidence of sublime sensation was largely out of date.

- Critical positions on the discourse of sublimity deny that Friedrich, who is distant from theory, can be assigned a visualization of such philosophical positions.

Image finding

Friedrich literally leaves the process of creating an image in the dark. He insists on the sensation of what is represented, which appears to him, as it were, from nothing before the inner eye.

“Close your physical eye so that you see your image first with the spiritual eye. Then bring to light what you saw in the dark, so that it affects others from the outside in. "

This statement suddenly separates the possible connection between the work process and the art historical, contemporary history, philosophical and literary traditions. In research there are very different theoretical approaches to explain the phenomenon of Friedrich's original image finding. In most cases, the problem is ignored and the painter, who is actually unrelated to theory, is associated with almost all of the literary and philosophical sources of his time relevant to Romanticism. Werner Hofmann basically denies the painter a strategic approach and considers the "dark total idea" founded by Friedrich Schiller to be a suitable term to describe this inner act of creation. What is meant by this is that all poetry begins in the unconscious and precedes the technical. Werner Busch comes to the conclusion that Friedrich could have been more naive than the unfolded horizon of thought would lead one to expect. No historical images are created, the present experience is the starting point. What is represented is not based on what was previously known, not on the mere implementation of a pre-existing text, and certainly not on what is derived from the tradition of literary romanticism. The chosen aesthetic order is decisive for the shape of the picture.

Romantic painter

Since the Tetschen Altar , Friedrich has been regarded by Werner Busch as a "kind of early romantic figure of identification" as well as the "epitome of the early romantic artist", with Joseph Leo Koerner as the "epitome of the romantic painter" and in Hans von Trotha's understanding the concept of romanticism has to be attached to the Painters claim. It is undisputed that Novalis ' definition is applied to Friedrich: to give romanticization a high meaning to the common, to the ordinary a mysterious appearance, to the known the dignity of the unknown and to the finite an infinite appearance. According to Werner Hofmann, the painter developed his own specific romanticism from this point of view. Many aspects of his desire for art touched one another with a general understanding of romanticism, but without coinciding with them. Friedrich can only be described as a romantic if one does not want to speak of "romanticism" but rather of "romanticism".

Mental illness

research

The beginning of the Friedrich research can be set around 1890 with the first texts by Andreas Aubert , whose fragments of a study on the forgotten Romantic 1915 the art historian Guido Joseph Kern had translated into German. In the period that followed, Richard Hamann and Cornelius Gurlitt tried to come to terms with the work with the concept of mood and to locate the painter as a forerunner of impressionism in art history.

Karl Wilhelm Jähnig made a first attempt to research the artist's work and compile a catalog raisonné on behalf of the German Association for Art History . Since he had to emigrate to Switzerland because of his Jewish wife , he was cut off from important sources. In Nazi Germany, the painter was appropriated from the perspective of Nordic racial ideology and his out-of-date religious side was suppressed. The publications by Kurt Karl Eberlein Werner Kloos , Kurt Bauch , Kurt Wilhelm-Kästner and Herbert von Eine produced during this time brought a number of new insights, but an unsuitable overall view of the work and the artist. The result was a distancing of the art business from Romanticism in the period after the Second World War.

At the end of the 1950s, Helmut Börsch-Supan's dissertation brought the painter back to research in the field of art under the impression of the economic upturn in non-representational painting. Gerhard Eimer's Stockholm lectures from 1963 on Friedrich's Gothic representations are still fundamental.

Under the conditions of divided Germany, the art historians of the GDR also discovered the painter's potential. With her Greifswald dissertation in 1963, Sigrid Hinz created important foundations for the dating of works and Willi Geismeier , director of the Deutsche Nationalgalerie Berlin, published his dissertation, which is still up -to-date , in 1966, which primarily names the sources of landscapes and religious beliefs. In the West in the late 1960s, Werner Sumowski created new interpretive approaches for numerous works with an extensive study. As a result of the 1968 movement, art history was politicized, which continues to divide research today. Friedrich was seen by a young generation of scientists as a victim of the reaction, and his religious views were largely interpreted politically.

In 1974, the catalog raisonné of Helmut Börsch-Supan, using the archive of Karl Wilhelm Jähnig, the catalog of the graphic works of Marianne Bernhard and the letters and confessions published by Sigrid Hinz provided a solid research basis.

In the following decades, a flood of scientific literature emerged, mostly to examine details of the work and especially in the context of large exhibitions. The research tended to shift from working with the sources to the formation of diverse theories, associated with names such as Hilmar Frank, Werner Busch, Jens Christian Jensen, Werner Hofmann or Peter Märker. There were now interdisciplinary theoretical approaches that included philosophical, psychological, psychoanalytic, psychopathographic or theological perspectives. Friedrich's texts were edited more precisely and critically. Several publications dealt with the identification of the real landscapes of the painter.

In 2011, Christina Grummt created a significantly improved working basis for research with the directory of all drawings and Nina Hinrichs published a history of Friedrich reception in the 19th century and under National Socialism for the first time.

reception

19th century

Most of his contemporaries perceived Friedrich as the painter of the north, both in terms of his reserved and closed manner and the motifs of his art. Through the theories of the sublime and sublime by Edmund Burke , Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller , a changed perception of nature led to the idea of a “sublime north” as a counter-image to the “beautiful classicist south”. This contrast is illustrated by the arcadia paintings of Classicism on the one hand and Friedrich's polar pictures such as The Ice Sea on the other.

"[Friedrich's fantasy] was not formed by a southern, serene, warm sky, by lush, rich, laughing areas, but by Nordic grandeur and grandeur [...]."

The Rügen pastor Theodor Schwarz wrote the novel Erwin von Steinbach or the spirit of German architecture under the pseudonym Theodor Melas in 1834 . The author provides the fictional character, the cathedral builder Erwin von Steinbach , with a painter named Kaspar, who is close to Caspar David Friedrich in his character and in his biography. Painter and pastor were good friends. Schwarz developed the protagonists' journey to the far north and beyond the Arctic Circle as a counter-program to the compulsory Grand Tour of the artists in Italy. In the world of sensation around 1800, the Ossian poems by James Macpherson assigned a melancholy mood to Nordic nature. To a certain extent, Friedrich fulfilled the expectations of the northern pictorial worlds, especially with his motifs from the island of Rügen, the landscape of which Kosegarten's poems gave Ossian features.

"His [Friedrich] two smaller pieces, the dilapidated hut under the snow, and the dark vault are composed in the same spirit [as the moonlit landscape on the Baltic Sea ] and remind us of similar short episodes in Ossian's chants."

Frederick's patriotic engagement was hardly noticed during the Napoleonic occupation, all the more so after the end of the wars of liberation. The oaks, barrows and Gothic buildings were read as national symbols in the romantic turn to a Germanic culture. However, as early as the middle of the 19th century, Friedrich was forgotten as a painter.

National Socialism

During the time of National Socialism , Friedrich's work was appropriated for propaganda purposes. The number of publications skyrocketed. His art was considered exemplary for National Socialist landscape painting and lifestyle. The Nordic topos was functionalized in the sense of the racially oriented Aryan myth . The selective political interpretation had already begun with the rediscovery of the painter at the beginning of the 20th century. His pictures were in the context of the National Socialist glorification of the liberation wars of 1813 and the view of Romanticism as “Germany's national reawakening to itself.” His naturalistic way of depicting landscapes and the clear technique set themselves apart from the criteria that were considered degenerate defamed artist apply. The country team made use of the works of Pomerania for the visualization of symbols of the blood-and-soil ideology . The artist's apparent Christian piety was reinterpreted into a pantheism as "piety of the Nordic kind" with the attribution of Germanic-mythical closeness to nature. The 100th anniversary of Friedrich's death was celebrated with numerous publications and his rediscovery by National Socialism was highlighted. The Art History Institute of the Ernst Moritz Arndt University of Greifswald was named Caspar David Friedrich Institute . The teaching staff at the institute published a commemorative book in which the artist's patriotism and patriotism were related to current war events.

“I call this life [Friedrich's life] a life of heroes. Because this lonely one remained victorious against all suffering and against all opposition in the world. He suffered and lived and became our shape. He, Caspar David Friedrich, stayed when it all sank, and he stays. His art is the great art of romanticism. In him the old Germanic genome comes to life again, the Nordic artistic spirit that glows away under the ashes. His soul art is the resistance art of the north against all art of representation of the south. This faithful painter saved a whole world. He defended Germany's artistic spirit against the West. [...] “The Rembrandt German” Langbehn was looking for is dead; but "the Friedrich German" lives and will live in art. "

The misuse of painters and works by the National Socialists was followed in the years after 1945 by the neglect of Frederick and Romanticism by the museums. The idea of a straight line from romanticism to Hitler persisted in Britain.

Reception in the GDR

Although the art historical research of the GDR also dealt with Friedrich, the state cultural policy initially found it difficult to find an appropriate place in the art-historical canon for the unadjusted landscape painter. The reference to the appropriation of Romanticism under National Socialism and the state cult around Goethe and Classicism were not conducive to Friedrich's reception. Regardless of this, broad sections of the population began to rediscover Romanticism in the early 1970s, as did in Germany. Friedrich's pictures became a projection surface for freedom and freedom. In 1979 Christa Wolf solved the problem in literature with the novel Kein Ort. Nowhere about Heinrich von Kleist and Karoline von Günderode an accompanying debate on the conflict between freedom and adaptation of the artist. The wanderer above the sea of fog was a metaphor for the self-reliant, free man who ponders his utopias while the fog hides the troubles of everyday life. Books and prints on the painter's work and biography achieved large editions. The Dresden exhibition on Friedrich's 200th birthday in 1974 came to 260,000 visitors, the counterpart in the Hamburger Kunsthalle 200,000. After this exhibition success, the GDR leadership recognized the cultural and political potential of the romantic. In 1974 the 1st Greifswald Romantic Conference took place at the Ernst Moritz Arndt University as part of the GDR's Caspar David Friedrich honor. However, it took until the mid-1980s for the painter to be celebrated in Dresden as the city's great genius and for a memorial in an abstract visual language in 1988.

21st century

At the turn of the millennium, the painter achieved an unprecedented international popularity. Over the past 30 years, Friedrich has risen to become the most famous German painter after Albrecht Dürer. From 1990 onwards there has been a dense series of large and small exhibitions and new publications every year. The large retrospective Caspar David Friedrich - The Invention of Romanticism in the Folkwang Museum Essen 2006 and in the Hamburger Kunsthalle 2007 is one of the modern, commercially successful blockbuster exhibitions with a total of 682,000 visitors. At the same time, significant works began to become trivial. The wanderer above the sea of fog, like Eugène Delacroix's freedom, has become a passe-partout symbol that people use for different purposes. Through the edge situation, the summit experience, the threat from the abyss, the physical end of a path of discovery or the open-mindedness of the motif, the hiker can be projected into different contexts or captured for it. The wanderer has found a place on magazine titles, record covers, book covers and in advertising . Caricatures satirize the motif. On the cover of the news magazine Der Spiegel No. 19 from May 18, 1995, the mountain climber dressed in urban clothing looks at a hodgepodge of icons under a black, red and gold rainbow that are supposed to represent the calamity of German history. Today this montage of images is considered a trivial icon of German consciousness.

Movie

The film Caspar David Friedrich - Limits of Time (1986) directed by Peter Schamoni deals with the reception of Friedrich's works. The painter himself does not appear in it personally, his life and work are told exclusively about other characters, in particular about his friend, the doctor and artist Carl Gustav Carus .

On behalf of the NDR, a historical documentation was produced in 2007 under the direction of Thomas Frick , which illuminates the interaction between mental suffering and the painter's works.

theatre

The picture Two Men Contemplating the Moon is said to have inspired Samuel Beckett on his six-month trip to Germany for his play Warten auf Godot in 1936 , as he admitted 40 years later to the theater scholar Ruby Cohn: This was the source of Waiting for Godot, you know . The two characters in the painting turned into the vagabonds Vladimir and Tarragon on the theater stage. Beckett replaced Friedrich's invitation to the viewer to contemplate with a provocation that is not about the content of the expectation, but about the questionable nature of waiting.

literature

Fritz Meichner undertook 1943 and 1971 the attempt to look at the life of the painter in the biographical novels Landschaft Gottes. A novel about Caspar David Friedrich and Caspar David Friedrich. Novel approaching his life .

Christoph Werner tells in 2006 in his novel To live forever. Caspar David Friedrich and Joseph Mallord William Turner the stories of the two romantic painters.

Effects in art

19th century

Friedrich won a place for landscape in modern art as an important genre. The effect among his contemporaries was limited to pupils and painter friends such as Carl Gustav Carus, Johan Christian Dahl, Ernst Ferdinand Oehme or Carl Wilhelm Götzloff. The monk by the sea , the abbey in the oak forest and the hiker above the sea of fog had great potential for inspiration .

In the second half of the 19th century, painters of realism and symbolism discovered the radical pictorial concepts of the romanticist for the further development of their landscapes. This is particularly true of James Abbott McNeill Whistler , Gustave Courbet , Arnold Böcklin and Edvard Munch . The strong presence of Friedrich's works in Petersburg collections showed a clear influence on the Russian realist landscape painters Archip Iwanowitsch Kuindschi and Iwan Iwanowitsch Schischkin . The Americans Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Albert Blakelock , as well as the artists of the Hudson River School and the New England Luminists were interested in the mystical allegories of the romantic .

Arnold Böcklin: Die Toteninsel , third version, 1883

20th century