The evening (painting)

|

| The evening |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1821 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 22.3 × 31 cm |

| Lower Saxony State Museum Hanover |

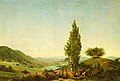

The evening is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, dated 1821 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 22.3 cm x 31 cm is in the Lower Saxony State Museum in Hanover . The painting is part of the cycle of times of the day, which also includes Morning , Midday and Afternoon .

Image description

The painting shows a light pine forest that takes up the entire picture space. The forest floor in brown-green tones is slightly wavy. A clearing with pine bushes fills the foreground. Red blooming flowers grow on the forest floor. The arrangement of the tree trunks appears rhythmic with larger distances towards the center. There the red-yellow light stratification of the sunset shimmers through. The sky above the horizon takes up two thirds of the picture area. Light and dark clouds pass over the treetops. In the center of the picture are two staffage figures clad in old German costume , looking towards the sunset, on a forest path that leads diagonally across the middle distance from the left.

botany

In the painting The Evening, as well as at noon and in the afternoon , pine forest dominates the character of the landscape. For the image idea of the evening , to be able to watch a sunset in the middle of the forest, pines are the only possible local tree species. Historically, extensive natural pine forests occurred primarily in the north-east German lowlands. Even with the occasional overexploitation of the forests, the pine in Friedrich's homeland has always been part of the typical forest landscape. At the beginning of the 19th century, the afforestation with pine trees began in Mecklenburg and Pomerania . The forest islands in the field that can be seen at noon are wood reserves that the farmers created for themselves. For the afternoon there is a pencil study Landscape with Tall Pine Trees and Horse-Drawn Carriage from 1798, which the painter largely used as a guide in the painting. The landscape shown in the drawing probably shows the land route between the Mecklenburg cities of Neubrandenburg and Neustrelitz .

Image interpretation

The evening is interpreted religiously, politically, philosophically and as a construction image in the context of Friedrich's picture cycles at the time of year and day. Like Morning , the painting is set in the painter's favorite state, twilight . The farewell to the day experiences a predominantly religious or nature-mystical ascription that has seen little change since ancient times.

“Twilight rises from the dark ground. With the end of the day the shadow of the night grows, sleep, this pre-existence of death, will receive us. "

The viewer confides in this image of nature. Helmut Börsch-Supan sees the forest, with Christian connotations, as a symbol of death and, in its permeability for light, the promise of the hereafter. With Friedrich these lines of thought are comprehensible, as lines from his poem Der Abend suggest:

"[...] Darkness covers the earth, but all knowledge is uncertain, the sky shines in the evening, clarity shines from above, senses and ponders as you like, death remains forever a secret, [...]"

The political interpretation of the picture is based on the old German costume of the staffage figures in the contemporary context of the persecution of demagogues after the Karlovy Vary resolutions of 1819. In art historical research, however, the meaning of the evening is not in the vicinity of such paintings as Two Men Contemplating the Moon or When the arbor is moved, the two hikers on the forest path are viewed in their staffage function. Like the “de-individualized” trees, people step back into complete anonymity. All traces of active life have disappeared from the picture, the wanderers do not belong to the daily work. It seems undisputed that the deeper meaning of the evening can only be understood in connection with the other pictures in the cycle.

Time and cycle

The origin of the time of day cycle has not been finally clarified. The morning and the evening were probably created as a pair of images, but the noon and the afternoon were added later. For Wieland Schmied , the allegorical in all four pictures takes a back seat to the concentration on the landscape and its gradual change. During the morning , the appearance of a creation in the morning, the afternoon , the clarity of the day, the afternoon is attributed to the envelope to bad weather, the owner of the evening the contemplation . Werner Hofmann also sees the iconic disappearance in this type of picture and demands that all cycles in the painter's work be included in the consideration. The times of day, seasons and ages turned into a continuum of transitions. The human path of life and the organic cycle of nature overlap. Dawn and falling evening, rise and fall, growth and decay, birth and death are pairs of terms that describe an overarching theme in Friedrich's art. The times of the day also include the seasons. The colors of the pictures tend to be autumn, in the afternoon the cornfield is ripe for harvest.

Construction picture

In 1966, Willi Geismeier recognized that Friedrich's time-of-day cycle could be assigned to texts in Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld's theory of garden art , which Detlef Stapf did not evaluate systematically until later. In his treatise, Hirschfeld characterizes gardens or landscape scenes according to the times of day. A reference text can be found in this discussion for the image The Evening . This is a quote from the book De la composition des paysages by the Marquis René Louis de Girardin published in 1777 , which reports on impressions while walking in his park in Ermenonville .

“When the coolness of the evening, observes a keen observer, spreads that lovely and graceful color which heralds the hours of rest and pleasure, then there is a sublime harmony of colors in all of nature. It was at such moments that Claude Lorrain chose the touching coloring of his calm paintings, where the soul and the eyes are at the same time captivated; at this time our eyes like to feast on a great landscape […] The masses of trees where the light shimmers through, under which the eye sees a pleasant walk; large areas of meadows, the green of which is embellished by the transparent shadows of the evening [...] light grounds of lovely shape and hazy color [...]. At these moments it seems as if the sun, ready to leave the horizon, likes to marry the earth with the sky before it leaves [...]. "

The back figures used by the painter as accessories apparently have the function of looking strollers. The Girardin text refers to the painting "Evening" from 1666 from Claude Lorrain's cycle of times of day.

Suggestion

The suggestion for Friedrich to deal with time cycles at all could have come from Philipp Otto Runge . Runge's times drawings were made in Dresden in the first half of 1803. In that year Friedrich produced the Sepia Spring - Morning - Childhood of his first cycle of times. A parallel to Runge's work results from the putti-like children present in the pictures . Whereby Runge, according to his own admission, was under the influence of Ludwig Tieck when developing his allegorical landscape theory . With the theme of the times, both painters evidently moved in the field of thought of early romanticism.

Provenance

Presumably the painting The Evening was acquired from the painter by Wilhelm Körte together with the Morning in July 1821. The owner was the Berlin doctor Friedrich Körte in 1906. The Lower Saxony State Museum bought the picture from the art trade in 1916. A copy of the painting on a wooden support (otherwise unknown to Friedrich) is listed in the Georg Schäfer Museum in Schweinfurt as a work by Friedrich himself. The picture was sold at an auction by G. Rosen in 1955 as the work of a successor to Friedrich.

Classification in the overall work

Friedrich started with his cycle of times of day, seasons and age as early as 1803 and repeatedly took up the topic in stylistic and motivic changes. With the pair of pictures, Summer and Winter , created in 1807/08, a concrete reference to the landscape was added to the iconic. A time-of-day cycle with sea motifs is dated to 1816. The presumably placeless time-of-day cycle of 1821/22 is the most self-contained cycle of times and is consistently oriented towards the pure effect of nature and the moods it creates. It also marks a stronger examination of the formal design possibilities of the time theme and the changes in nature. The subsequent Hamburg cycle of seasons and ages with cepias from the period between 1826 and 1834 is considered a faint reminiscence of the series that began in 1803.

The evening motif

The evening motif is present throughout the painter's work regardless of its location in one of the time cycles. The evening seems to the painter to be the time of day when he can best recognize the divine in nature. The sunset and the twilight, the rising of the moon and the evening star reveal an everlasting secret to him. In his pictures he is able to give the impression that this process is something that has never been seen in nature. The viewer feels the haunting message that our existence is a life leading to death, the evening is a gateway to it. This allegory is told anew and in surprising ways in pictures such as the mountain landscape with rainbow (1810), the Tetschen Altar (1808), the stages of life (1835), the monk by the sea (1810), Neubrandenburg (1817) or the memorial picture for Johann Emanuel Bremer (1817).

"The twilight was his element, early in the first morning light a lonely walk and also a second in the evening at or after sunset, although he liked to be accompanied by a friend: these were his only distractions;"

“In the evenings I walk across fields and meadows, the blue sky above me, around and next to me green seeds, green trees, and am not alone; for he who created heaven and earth is around me. "

The hiker motif

The two hikers on the forest path of the clearing in the painting The evening stop, pause and watch the sunset. The staffage reinforces the effect of the natural event, already sets the basic tone in the relationship between the viewer subject and the nature depicted in the picture. The figures are connected to the metaphor of the view and refer to a space of anticipation. The perception of the landscape itself becomes part of the motif and charges the actual motif with meaning. For Friedrich, art is not just a representation, but a perception of nature. The wanderer motif is present in all of the painter's creative periods. The hiker or hikers do not always have a staffage function, they are assigned their roles in the picture narration mainly based on their biographical background. Instead, there are paintings such as Two Men Contemplating the Moon , a mountain landscape with a rainbow , hikers above the sea of fog or Neubrandenburg . For the frequently used staffage function, Friedrich created a type of figure in old German costume that emerges most clearly in the silhouette-like evening landscape with two men (around 1830/35). There a premonition of the landscape on the seashore is contrasted with the shadows of the two figures. Hilmar Frank thinks it is forbidden to speak of staffage when looking into the distance, because this term is reminiscent of the studio habit of landscape revitalization. With Friedrich, however, the figures would question the landscape.

Construction images

Among the previously known images based on texts from Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld's theory of garden art , Der Abend and Der Morgen are among those with a very direct implementation and minimalist semantics . The evening can be seen as a starting point for a more intensive study of Hirschfeld's compendium in the old work. In the paintings to be dated afterwards based on Hirschfeld texts such as The Great Enclosure (around 1832), Eldena Ruins in the Riesengebirge (1830/34) or Juno Temple in Agrigento (1830), the subjects developed according to far more complex issues. In any case, it is about creating moods in the landscape depicted.

The evening motif in art

With the evening motif, Friedrich is thematically in the tradition of Baroque painting, simply through the Girardin text and the reference to the painting of Claude Lorrain's evening and its inclusion in its cycle of times of day. Of Friedrich's contemporaries, Karl Friedrich Schinkel is still close to Lorrain with his cycle of times of day, created in 1813/14. Friedrich's student Carl Gustav Carus shows a clear relationship to the work of his teacher in many of his evening motifs. William Turner revolutionized landscape painting in England with the evening mood of nature. Later generations of painters were influenced by the theme from the Romantic period, which names such as Gustav Klimt, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet or Edvard Munch stand for. Gustav Klimt's Tannenwald series refers most clearly to Friedrich's evening .

Web links

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné)

- Hilmar Frank: Prospects for the immeasurable. Perspectivity and open-mindedness with Caspar David Friedrich . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2004

- Willi Geismeier: On the importance and developmental position of a feeling for nature and landscape representation in Caspar David Friedrich . Dissertation, Berlin 1966

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011

- Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974

- Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben und Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0

- Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999

- Wieland Schmied: Caspar David Friedrich. Cycle, time and eternity . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1999

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters . ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-936406-12-X

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 104

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 251, network-based P-Book

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 201

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 365

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 77

- ^ Wieland Schmied: Caspar David Friedrich. Cycle, time and eternity . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1999 p. 28

- ^ Wieland Schmied: Caspar David Friedrich. Cycle, time and eternity . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1999 p. 25

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2007 p. 208

- ↑ Willi Geismeier: On the importance and developmental position of a feeling for nature and landscape representation in Caspar David Friedrich . Dissertation, Berlin 1966, p. 107

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 251, network-based P-Book

- ^ Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben and Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785, Volume 5, p. 15

- ^ Werner Sumowski: Caspar David Friedrich studies . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1970 p. 81

- ^ Philipp Otto Runge: Letter to Ludwig Tieck, December 1, 1802 . In: Legacy Writings. Published by his eldest brother . Volume 1, Hamburg 1840, p. 24

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 365

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 194, network-based P-Book

- ^ Wieland Schmied: Caspar David Friedrich. Cycle, time and eternity . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1999 p. 5

- ^ Carl Gustav Carus: Memoirs and Memories . Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag, Weimar 1965/66, Volume 1, 165 f.

- ^ Hermann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters . ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006, p. 168

- ↑ Hilmar Frank: Prospects into the immeasurable. Perspectivity and open-mindedness with Caspar David Friedrich . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2004; P. 6 f.

- ↑ Hilmar Frank: Prospects into the immeasurable. Perspectivity and open-mindedness with Caspar David Friedrich . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2004; P. 5

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 252, network-based P-Book