Tetschen Altar

|

| Tetschen Altar (cross in the mountains) |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1807/08 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 115 x 110.5 cm |

|

New Masters Gallery in the Albertinum State Art Collections Dresden |

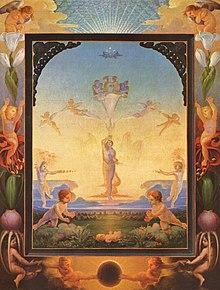

Tetschen Altar , also called The Cross in the Mountains , is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich from 1807/1808 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 115.0 cm × 110.5 cm (rounded at the top) is in the New Masters Gallery of the Dresden State Art Collections . The frame was carved by the sculptor Christian Gottlieb Kühn , has the dimensions 173 cm × 176.6 cm and stands on a base 10 cm high. The painting is one of the painter's manifesto pictures and is considered an icon of romantic art.

Image description

motive

The almost square picture, trimmed in a rounded head, shows a rocky mountain peak overgrown with fir and spruce trees, on which an ivy-entwined crucifix is erected. The Corpus Christi, which the viewer sees in the side profile, is illuminated by the sun setting behind the mountain. The rays of the sun in front of the reddened sky covered with clouds are fan-shaped as sharply contoured light paths.

Painting technique

The painting has a graphic character in the close up view of the details. Every detail has its carefully calculated place. Friedrich developed a process from the sepia technique that enables dark glazes to show through to the background of the picture. The details are first sketched out with a pencil on a light primer and then reinforced with a tube pen. The painting is then carried out with several thin layers of glaze in different shades . This creates a different visual experience from a distance and at a short distance.

frame

The painting is framed by a golden neo-Gothic frame designed by the painter himself. The center of the lower frame surface forms a triangle with an all-seeing eye backed with stylized rays of the sun, vaulted on the left by a sheaf of wheat and on the right by a vine. The sides of the frame are formed by two fluted Gothic columns that look like trees from which palm branches seem to grow out. Five chubby chubby putti / angel heads peek out from between the palm leaves, which are bent against each other . A morning or evening star is attached to the zenith of the rounded frame.

Work history

Procurement

The award of the contract for the altar has not yet been clarified. It is also possible that there was no commission for the picture. Until the late 1970s, according to the genesis described by Otto August Rühle von Lilienstern in 1809, art historical research assumed that Count Thun-Hohenstein commissioned the altar for the chapel of his castle in Tetschen, which was still to be built . According to the correspondence of Countess Thun-Hohenstein found in 1977, the cross in the mountains was already ready when the painter received the offer to buy. The alleged reason for his initial refusal to sell the picture is conveyed.

“Unfortunately the beautiful cross is! Not available! The good north has revered it to his king, and although he has no opportunity to send it to him, and by then he could probably make a few other pieces, he does not want to give it. "

This note favored the legend that the altar was intended for King Gustav Adolph IV of Sweden , who ruled over Swedish Pomerania . This was followed by the political interpretation of the picture with an anti-Napoleonic tendency. The altar never saw a chapel in Tetschen Castle, but was in the bedroom of Countess Thun-Hohenstein next to a copy of Raphael's Dresden Sistine Madonna .

As early as 1939, Kurt Karl Eberlein published the variant that Friedrich painted the "landscape altar three times - for Countess Thun, for the princes of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Gotha-Coburg". The latter refers to the patron and art collector Duke August of Saxe-Gotha and Altenburg , who resided in Friedenstein Castle in Gotha during the French occupation . The Duke probably knew the Tetschen Altar, because he described Gerhard von Kügelgen's contribution to the "Ramdohrstreit" (see below) as a "badly successful defense of Friedrich's Altar Platitude". Gotha Castle does not offer any spatial situation for which such an altar could be designed. The commission could also be the painting Cross in the Mountains (Der Ilsenstein, Crown of Thorns) from 1823 , which can be seen today in the Gotha Castle Museum.

Friedrich stayed several times in the park landscape of Hohenzieritz Castle , the summer residence of Duke Karl II of Mecklenburg-Strelitz , and pictures can be assigned to the park landscape. The chapel of the castle would be a suitable place for the cross in the mountains . A measurement of the altar niche has shown that it could accommodate Friedrich's altar with an accuracy of one centimeter, including the plinth located in the depot of the Dresden art collections at the height of the baseboard of the church. As has been handed down, the painter “calculated the altar for the entire area around its future destination”. There are a number of other indications for this destination, but ultimately no reliable source for the award of an order by the Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Dresden presentation

When Friedrich announced in Dresden that he would sell the picture to Count Thun-Hohenstein, he was urged in mid-December 1808 to show the altar to a wider public. The painter initially protested against this presentation on the grounds that the picture and frame would not come into play outside the intended environment and would be torn out of context.

“In the meantime, he gave in to the urgent wishes of his friends and acquaintances, and since the number of sightseers had increased daily, he decided to display it in his apartment for a few days in his absence to look at. To counter the evil effect of the completely white walls of his little room in something and to imitate the twilight of the chapel, which was lit by lamps, as best one could do it, a window was curtained, and over the table on which the painting, which for an ordinary one The easel had become much too heavy anyway, was raised and a black cloth spread out. "

“Yesterday I made the first exit and just went over the Elbe to Friedrich to see an altarpiece. I found many acquaintances there, including Chamberlain Riehl and his wife, Prince Bernhard, Beschoren, Seidelmann , Volkmann, the Barduas, etc. Everyone who stepped into the room felt as if they were entering a temple. The biggest screamers, even scorned, spoke softly and seriously like in a church. "

Friedrich did not spend the Christmas days in Dresden, but most likely traveled to Breesen . It is believed that the painter received the news around December 20th that his favorite sister Catharina, who was also his mother's substitute, was struggling with death. The pastor's wife died on December 22nd, 1808. On October 22nd, she wrote in her last letter to her brother:

“Have you finished the altar piece? I would like to see it, I think it will make a lot of impression. "

This course of events suggests that Friedrich set up the altar for devotion to his sister.

Sale and current location

In 1808, Count Franz Anton von Thun-Hohenstein acquired the cross in the mountains from Friedrich for his wife, Theresia Maria, née Countess Brühl. Hans Posse bought the altar in 1921 for the Dresden picture gallery from the property of Count Franz von Thun-Hohenstein in Tetschen. Today it is in the New Masters Gallery of the Dresden State Art Collections.

Image interpretation

The Děčínská altar may be between the basic tendencies of political and naturmystisch-early romantic interpretations as the most discussed and provided with theories created by Frederic seen. Even though the painter provided his own commentary on his picture and the frame provided a broad definition of meaning. Despite all the differences in the assessment, the cross in the mountains is considered a painted manifesto that proclaims the iconization or sacralization of the landscape. With the Ramdohr dispute of 1809, basic questions of art were raised, some of which are still discussed today. So the question is still in the room: Does the cross in the mountains represent a landscape at all, if the material consistency of the crucifix described by Friedrich indicates an interior object?

Whereas at the beginning of the 19th century the legitimacy of breaking traditions in landscape painting was at stake, the modern art-historical debate aims to explain the painter's actual intentions through political, theological, philosophical, psychological, literary, art-theoretical and stimulating contexts. Helmut Börsch-Supan still considers the interpretation written by Friedrich himself to be the most important source to get to the meaning of the work.

Ramdohr dispute

In response to the Dresden presentation of the altar, a devastating essay by Friedrich Wilhelm Basilius von Ramdohr appeared in January 1809 . The Prussian diplomat, himself a portrait painter and caught up in classicist aesthetics, criticizes the violated rules of traditional image composition in Friedrich's work, the transgression of the boundaries of the landscape painting genre , the lack of expressiveness of allegory and the inadmissible combination of landscape painting and sacred art. Ramdohr's standards in art are landscape painters of a bygone era such as Claude Lorrain , Nicolas and Gaspard Poussin and Ruisdael . The normative genre aesthetics he used was developed in the 17th century, the central perspective unit area in the 15th century. In his accusations against the painter, the critic uses a denouncing vocabulary in the basic tone.

From the point of view of the viewer, Ramdohr finds errors that offend the “rules of optics” and extensively examines the contradictions that the picture offers in terms of its motif and structure. The core criticisms are the non-existent central and aerial perspective, the non-functioning interlocking of near and distant vision, the flat representation of the rocks, the lack of spatial depth or unsuccessful lighting.

“The painter did not take or could not accept a point of view in order to express what he wanted to express. In order to see the mountain at the same time as the sky in this extent, Mr. Friedrich would have had to stand several thousand steps at the same height as the mountain and so that the horizontal line ran flush with the mountain. "

Basically, Ramdohr denies the suitability of landscape in art for allegorizing a religious idea or for awakening devotion. At most a pathological but not an aesthetic emotion emerges from this.

“Indeed, it is a true presumption when landscape painting tries to sneak into churches and crawl on altars. [...] That mysticism that is now creeping in everywhere and, as if from art as from science, from philosophy as from religion, storms towards us like a narcotic vapor! "

The Ramdohr article sparked a hitherto unknown debate about a contemporary work of art and documents the change in the effect of art in the Romantic era. Ultimately, the question was discussed whether landscape can convey religious content and in what way. The painters Ferdinand Hartmann and Gerhard von Kügelgen as well as the writers Christian August Semler and Rühle von Lilienstern wrote polemical responses to Ramdohr's criticism, in which, above all, new paths in art are advocated. Ramdohr responded to Hartmann's and Kügelgen's pleadings.

Friedrich reluctantly spoke up with a printed letter in the third person to the academy professor Johannes Karl Ludwig Schulze , in which he defended his new path.

"If the picture of the painter Friedrich had been made according to the rules of art that have been sanctified and recognized for centuries, that is, in other words: if Friedrich had used the crutches of art and had not had the presumptuousness to want to walk on his own two feet, sir Chamberlain von Ramdohr would never have let himself be disturbed from his calm. "

The real reason for this art theoretical dispute was provided by Friedrich's refusal to disclose the image concept developed for a specific prayer room. He preferred to admit technical errors in part and insist that “there is not just one single path to art”. In his own picture interpretations, insofar as they are reproduced correctly, Friedrich does not appear particularly credible. In the interpretation handed down by Rahmdohr, the sun rises in the picture and in that handed down by Christian August Semler the sun goes down, an essential difference that affects the central message of the picture.

Own interpretation

For the interpretation of the cross in the mountains, the painter's own interpretation, which he felt compelled to give in the course of the Ramdohr debate, provides the christological framework:

“It is intended that Jesus Christ, pinned to the wood, is here turned towards the setting sun, as the image of the eternal, all-living Father. An old world died with Jesus' teaching, the time when God the Father walked directly on earth; where he said to Cain: Why are you angry, and why are your gestures disfigured? where under thunder and lightning he gave the tables of the law; where he said to Abrahm, Take off your shoes; because it is holy land where you stand! This sun sank, and the earth could no longer grasp the departing light. The Savior on the cross shines from the purest noble metal, in the gold of the evening red, and thus shines again in a softened shine on earth. The cross stands erect on a rock, steadfast, like our faith in Jesus Christ. Always green through all the ages, the fir trees stand around the cross, like our hope in him, the crucified. "

Motivational stimulation

The starting point of the numerous theories about the Tetschen Altar is usually the question of the motivic stimulus for the work. The most common approach relates to Friedrich's acquaintance with Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten and his famous shore sermons at Vitt auf Rügen , as a fundamental connection between worship and nature. The pastor wanted an altarpiece for his chapel, which was then executed by Philipp Otto Runge . Runge's 1808 similar iconization of the landscape in the painting The Little Morning is used as an opportunity to influence .

Ludwig Teck's novel Franz Sternbalds Wanderings from 1789 was introduced into the discussion from literature . Werner Sumowski sees the influence of the doctrine of natural philosophy on Friedrich. The natural philosopher of Romanticism Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, who was friends with Friedrich, comes into question here. Friedrich could also have received suggestions from Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld's theory of garden art, which he used . Forest altars made of rocks and fir trees were often elements of landscape parks at the end of the 18th century.

Structure and aesthetics

The structure of the picture reveals a stencil character through the backlit mountain and spruce trees. The location of the viewer in front of the picture cannot be made out, it seems to be suspended. This phenomenon cannot be explained under the conventions of landscape painting. Werner Sumowski and Detlef Stapf offer an explanation by assuming the painter to use an abstract geometry that is covered or overmolded with landscape elements. When Friedrich gives a material idea of the figure of Jesus in his own interpretation of the picture, which excludes a weathered summit cross (“There shines, made of the purest noble metal, the Savior on the cross ...”), the mountain adapts the base of an artfully crafted crucifix.

In the square-shaped frame with a symmetrical frame, the golden ratio is used as the most common structural principle, although Friedrich uses numerous other, mostly geometric, structural methods. In a classic way, the right vertical line is the location of the hero, that of the cross of Christ. The left vertical runs through the center of the hidden sun. The lower horizontal line touches the base of the cross. The upper horizontal line cuts the corpus without any obvious function, but marks the transition of the picture to the upper rounding and the end of the fluted columns of the frame.

theology

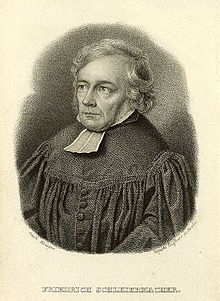

With his own interpretation, the painter raises the question of whether the cross in the mountains (like other of his paintings) is to be understood as a painted theology or at least is in a contemporary theological context. There are two basic lines of interpretation for this. Klaus Lankheit, Werner Busch and Werner Hofmann see Friedrich's departure from traditional formal language as a parallel to the confessional writing on religion. Speeches to the educated who despised the philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher , who called for a religious renewal. With his thesis that religion is neither thought nor action, but rather intuition and feeling, Schleiermacher is close to Friedrich's views on art as worship and feeling as the artist's law.

Willi Geismeier identifies the influence of the Christian revival in Friedrich , with the emphasis on the awareness of sin and the need for grace and redemption. Detlef Stapf sees the early revival theologian Franz Christian Boll with his treatise On Decay and the Restoration of Religiosity a key word for the painter's religious subjects.

It cannot be ruled out that Martin Luther's Theologia crucis, widely discussed in the theological debates at the beginning of the 19th century , may have donated the idea for the Tetschen Altarpiece .

Werner Sumowski's view that Friedrich's crosses in the landscape are a Christian-centered pantheism no longer seems relevant in today's art-historical debates.

Masonic program image

According to the symbolism and composition, Hubertus Gaßner considers the Tetschen Altar to be a Masonic program picture , which the painter dedicated to the Swedish King Gustav IV Adolf, Grand Master of the Greifswald Masonic Lodge. Friedrich's membership in the Johannes Lodge "Carl zu den Drei Griffin" is assumed, even though the painter is not listed there. Anna Mika also analyzes the picture from the point of view of hidden geometric figures from the Masonic initiation program and clearly recognizes the “seven-step ladder to heaven”. If the Tetschen Altar was designed for the chapel in Hohenzieritz, then the painter would have orientated himself on the interior symbolism of the church of the Freemason Duke Karl II of Mecklenburg-Strelitz . Detlef Stapf finds elements of the picture, such as the all-seeing eye in the frame, in the sacred furnishings of the room there.

Religious-patriotic symbolism

Jost Hermand sees the picture as a “new-German, religious-patriotic” work that is interspersed with “symbols of conviction”. The spruce as well as the Gothic (the pointed arch of the frame) are patriotic symbols for Friedrich. With its mood of death and resurrection, the picture expresses the mourning for the sacrificial death of Christ and the mourning for the empire that perished in 1806 (the defeat of Prussia meant that the painter had to stay in bed for weeks); but at the same time there is also the hope of his resurrection. It represents the desire to “restore old German Christian conditions” by ending the oppression by the “Welsh antichrist” Napoleon. “Pietistic and patriotic” entered into a close synthesis. It is noticeable that the depictions of the cross increased particularly frequently in the period from 1806, the end of the Holy Roman Empire , to the beginning of the Wars of Liberation in 1813. This year he signed a spruce study: "Prepare yourselves for a new fight today, German men, hail your weapons."

Classification in the overall work

Development of the subject

The Tetschen Altar as a complex work has a motivic lead. The painter approaches the picture from two directions. On the one hand with the formation of mountainous summit landscapes, on the other hand with the depiction of the crucifix in nature.

Friedrich did not only deal with the divine light of the sun and Christ on the cross at the Tetschen altar . His first notable artistic success in the Weimar Prize Tasks in 1805 with the sepia sheet Pilgrimage at Sunrise , for which he received half of the first prize, deals with this subject. In this scene of a monk's procession from the pre-Reformation period, the sun rising in the east shines on the host carried in the procession, while Jesus stands on the cross in nature facing west in the dark shadow. Against this background, the Tetschen Altar could be read as a manifesto of Protestant theology.

With the cross in the landscape, the painter has been concerned with the drawings Rocky Forest Landscape with Cross and River Landscape with Cross since 1798 at the latest . A motif development in the sense of preliminary stages then takes place in the Sepien Mountains Landscape (1804/05) and Mountains in the Fog (1804/05) as well as in the paintings View of the Elbe Valley (1807) and Morning Fog in the Mountains (around 1808).

A further development of the cross in nature theme can be seen in the following years. There he painted the paintings Morning in the Riesengebirge (1810), Winter Landscape with Church (1811) and Cross in the Mountains (1812). In this overall view, the Tetschen Altar is not an isolated event in the overall work, but was part of a series of representations of the cross with a programmatic claim in the period between 1805 and 1812. After 1812, the cross motif hardly played a role in nature, except in the cemetery representations and the Gotha Cross in the mountains .

The altar designs

The Tetschen Altar is not the only altar that Friedrich designed. Several altar studies were carried out around 1818, especially for the order for the furnishing of the Stralsund Marienkirche that was not carried out . A watercolor is dated to the year 1816/17, which takes up the motif of the cross in the mountains again and is known under the title Cross in front of a rainbow in the mountains . A note on the sheet that did not come from the painter qualifies the design as a study of the Tetschen Altar . However, there is no further evidence for this. Due to the rainbow, one can assume a memorial altar. With a few subsequent changes, which are sketched in pencil on the sheet, the altar (without painting) corresponds to the neo-Gothic main altar erected in the Marienkirche in Neubrandenburg in 1841 and destroyed in 1945.

Tradition of the representation of the cross

The representation of the cross in Renaissance and Baroque art was often associated with the element of landscape. In addition to the Jesus on the cross as a Christian icon, the narrative background of the biblical event was brought into the picture. In this respect, Friedrich and his cross in the mountains are part of the tradition of designing this religious motif. He also breaks with the tradition of central perspective, but innovatively takes up the structures of the medieval image and the icon. His Spanish contemporary Francisco de Goya also works with the divine triangle in an illusionary space in the painting Adoration of the Name of God .

reception

The history of the reception of the Tetschen Altar , which is charged with opposing positions, begins in 1808 and has left behind a barely manageable abundance of material. In the 1980s, the picture was also perceived as a central work by Friedrich in the art-historical discourse in the USA. In the last major Caspar David Friedrich exhibition The Invention of Romanticism in 2006/07 in Essen and Hamburg , the Tetschen Altar was exhibited as a major work.

Contemporary novel

The Rügen pastor Theodor Schwarz wrote the novel Erwin von Steinbach or the spirit of German architecture under the pseudonym Theodor Melas in 1834 . The author provides the fictional character, the cathedral builder Erwin von Steinbach , with a painter named Kaspar, who is close to Caspar David Friedrich in his character and in his biography. Painter and pastor were good friends. Schwarz takes up the fact that the Tetschen Altar was designed as a commissioned work for a house chapel. In the novel, Kaspar is commissioned by the Archbishop of Lund to make an allegorical landscape for his house chapel.

Contemporary Arts

The artist Sebastian Wanke presented an interpretation of the Tetschen Altar in the Sacred Heart Church in Erlangen at the waste and void exhibition (contemporary art in sacred space) in 2019 . His Erlanger altar with summit cross shows a 20-minute digital animation in an endless loop. The installation and the digital mountain landscape make specific reference to Friedrich's painting.

Nazi propaganda

The Nazi propaganda used the story of Děčínská altar in comparison to the political situation in the Sudetenland in the article The cross in the mountains in the newspaper Die Zeit. Official organ of the NSDAP Sudetenland .

“Doesn't it sound strange; When Caspar David Friedrich painted the picture, the German people were subjugated by the cocky Corsican; when it returned from Tetschen Castle to Dresden (in Kaufweg) the Sudetenland was not free. Soon after the picture left Dresden, Germany became free, as Caspar David Friedrich and his friends had longed for for years and for which they fought. And soon after the picture left Tetschen, the Sudetenland became free, returned home to the Reich and no more border posts protrude between us and the picture 'The Cross on the Rock', to which we Sudeten Germans feel connected. "

The historical background of the article is the incorporation of the Sudeten areas into the German Reich in 1938. For country team politics, artists were used to visualize symbols of the blood-and-soil ideology .

Friedrich's works were also racially appropriated. Landscape painting under National Socialism represented "racial art and visible racial thoughts of the peoples". The interpretation of the repertoire of forms was about "the inner life of the northern Gothic spirit". To the cross in the mountains it says:

“[...] like candlesticks on the altar, his fir trees stand around the cross, sticking out like candles. The inner Gothic of these trees is evident, even if they do not tower next to the Gothic gable, so I have called them 'Gothic trees'. These gabled firs grow out of the Nordic spirit, whose Gothic could never die. "

Sketches and studies

The sketches for the picture and the sepia used as a preliminary study testify to the detailed preparation of the painting, but also to the use of the large reservoir of drawings by the painter.

| image | title | year | size | Image position | Exhibition / collection / owner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rock study, steps on the right | 10./12. August 1799 | 19 × 24.2 cm, pen, washed | Rock piece to the right of the cross | Kupferstichkabinett , National Museums in Berlin |

|

Rock studies | around 1806-08 | 18.2 × 11.8 cm, pencil | Rocks under the two large fir trees on the left, both rocks below

[...] with a flat slope, mirror image |

Oslo, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design , National Gallery |

|

Spruce | May 2, 1807 | 37.7 × 24.1 cm, pencil | 1. Fir tree to the right of the cross | Oslo, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, National Gallery |

|

Six studies of spruce and fir trees | April 30, 1807 | 37.7 × 24.1 cm, pencil | 1st fir to the left of the cross and penultimate fir | Oslo, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, National Gallery |

|

Spruce | May 3, 1804 | 18.4 × 11.8 cm, pencil | 2. Fir | Privately owned |

|

Fir and three studies of spruce | May 1, 1807 | 37.7 × 24.1 cm, pencil | 3rd fir tree on the left | Oslo, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, National Gallery |

|

Pine Studies | April 13, 1807 | 37.7 × 24.1 cm, pencil | 3 small pines | Oslo, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, National Gallery |

|

The cross in the mountains | around 1806/07 | 64 × 92.1 cm, sepia | Preliminary study, converted into a portrait format for the altar | Kupferstichkabinett, National Museums in Berlin |

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan , Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné).

- Werner Busch : Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion. Publishing house CH Beck, Munich 2003.

- Hilmar Frank: The "Ramdohrstreit". CD Fr's "Cross in the Mountains". In: Dispute over images. From Byzantium to Duchamp . Edited by Karl Möseneder . Dietrich Reimer, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-496-01169-6 , pp. 141-159.

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011

- Karl Ludwig Hoch: On CD Friedrich's most important manuscript. And: The so-called Tetschen Altar by Caspar David Friedrich . In: Pantheon 39, 1981

- Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974

- Werner Hofmann: Comments on the Tetschen Altar by CD Friedrich. In: Christian Art Journal. 100, 1962, pp. 50-52

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Werner Sumowski: Caspar David Friedrich studies . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1970

- Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006

Web links

- Tetschen Altar in the Online Collection of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Individual evidence

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 46

- ↑ Rühle von Lilienstern: A painter's journey with the army in 1809. Rudolstadt 1810, pp. 42–44

- ↑ Eva Reitharovà, Werner Sumowski: Reviews of Caspar David Friedrich, In: Pantheon 35, 1977, page 43

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 36

- ^ Karl Ludwig Hoch: On CD Friedrich's most important manuscript. And: The so-called Tetschen Altarpiece by Caspar David Friedrichs In: Pantheon 39, 1981, Fig. 324

- ^ Kurt Karl Eberlein: Friedrich the landscape painter. In: Genius II, 1st book, 1939, p. 39

- ^ Wolf von Metzsch-Schilbach: Correspondence between a German prince and a young artist. Berlin 1893, p. 216

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 385

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 181, network-based P-Book

- ^ Sigrid Hinz (ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in Letters and Confessions , Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 179 f.

- ^ Rühle von Lilienstern: A painter's journey with the army in 1809 . Rudolstadt 1810, p. 42 f.

- ^ A. and E. von Kügelgen: Helene Marie von Kügelgen, b. Zoege from Manteufel. A picture of life in letters . Belsersche Verlags-Buchhandlung, Stuttgart 1922 p. 58

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters . ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006 p. 45 f.

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 46

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 301

- ↑ Newspaper for the Elegant World from January 17 to 21, 1809

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 141 f.

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 149 f.

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 152f.

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 152f.

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 133.

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 137.

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters . ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006 p. 53

- ^ Werner Sumowski: Caspar David Friedrich studies . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1970, p. 239

- ^ Werner Sumowski: Caspar David Friedrich studies . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1970, p. 42 ff.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 184, network-based P-Book

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, 43 f.

- ^ Klaus Lankheit: Caspar David Friedrich and the New Protestantism . In: German quarterly journal for literary studies and intellectual history 24, 1950, pp. 129–143

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 159 ff.

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 50 ff.

- ↑ Friedrich Schleiermacher: About religion. Speeches to the educated among their despisers . Stuttgart 1993

- ↑ Willi Geismeier: On the importance and developmental position of a feeling for nature and landscape representation in Caspar David Friedrich . Dissertation, Berlin 1966, p. 118

- ^ Franz Christian Boll: On the decay and restoration of religiosity . Volumes 1 and 2, printed by Ferdinand Albanus, Neustrelitz 1809/10

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 126, network-based P-Book

- ^ Werner Sumowski: Caspar David Friedrich studies . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1970, p. 110

- ↑ Hubertus Gaßner: For guidance. In: Caspar David Friedrich. The invention of modernity. Exhibition catalog Essen / Hamburg, 2006/2007, p. 14

- ^ Anna Mika: Caspar David Friedrich. Inauguration images with symbols of the Masonic Order in a ritual hidden geometry. Series of publications "Geometric Structures of Art", Books on Demand GmbH Norderstedt 2007, p. 80 ff.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 183, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Jost Hermand: Avant-garde and regression. 200 years of German art. Leipzig 1995, p. 14 ff.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 236

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 267

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 281

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 282

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 297

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 46

- ^ Joseph Leo Körner: Caspar David Friedrich and the subject of landscape . London, Reaction Books 1990

- ↑ Theodor Schwarz (pseudonym Theodor Melas): Erwin von Steinbach or the spirit of German architecture . Hamburg 1834, part 1, 2nd book, p. 397 f.

- ↑ WASTE AND VOID - ARTISAN. Accessed January 2, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Xaver Schaffer: The "Cross in the Mountains". Fates of a famous painting . In: The time . Official organ of the NSDAP Sudetenland, 3 XII., 1939, episode 334, no p.

- ^ Karl Kurt Eberlein: Friedrich the landscape painter . In: Genius II, 1st book, 1939, p. 6 f.

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 185

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 435

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 510

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 506

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 389

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 507

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 496

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 474