Gazebo (painting)

|

| Gazebo |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1818 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 30.0 × 22.0 cm |

| New Pinakothek Munich |

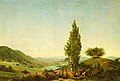

Gartenlaube is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich from 1818 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 30 cm × 22 cm is in the Neue Pinakothek Munich .

Image description

A man and a woman are depicted behind a pergola , which apparently serves as the end of a gazebo. It could be a married couple. The man with a stocky stature and lush-looking, curly hair on the back of his neck wears a coat like a beret in traditional German costumes . The woman, sitting on a chair, looks solemn in her yellow floor-length dress and a red shawl. Their white lace collar is also the most important feature of the old German costume. Both figures look in a longing gesture in the direction of a church in the neo-Gothic style . In the middle distance of the three-cycle image structure, strong vegetation serves as a space barrier between a Biedermeier scene and a sacred building that soars into the sky, which appears unreal due to light emanation . The two people are anonymized as back figures.

Image interpretation

The painting was first published in 1944 by Paul Ortwin Rave in the art magazine Kunst für alle . All interpretations made since then assume that the picture deals with a religious or at least a religious theme. The motif of the sacred building in front of the moonlight conveys a fairly clear message in the picture narration through the comparable symbolism used in Friedrich's work, without having to know the actual background for the creation of the picture. Helmut Börsch-Supan provided the updated interpretation with which the view from the arbor at the church is to be understood as an expectation of the afterlife in the humble earthly dwelling.

Image composition

Gerhard Eimer describes the gazebo as an exemplary example of the image design of the "window to the soul". This reference to Leonardo da Vinci's metaphor “The eye is the window to the soul” captures the viewer through the anonymity of the back figure in the longing perspective of the two depicted people. This also largely determines the meaningfulness of the image areas. The foreground and background are assigned different time dimensions by the respective motifs. The old German costume of the two people places them in a concrete contemporary context of the persecution of demagogues . The lack of soil and space in the church gives the building an unreal, transcendent character, whereby “something that is no longer real or something that is not yet real” remains uncertain. In the three-cycle, finely balanced, symmetrical picture structure, the arbor wall and the dense vegetation act as a barrier and reinforce the separation of foreground and background.

botany

Botanically determining the plant tendrils on and in front of the arbor wall is considered relevant because the plant symbol is used for the interpretation. Sun recognizes Helmut Borsch-Supan one entwined with grape arbor, where he suspects the vines as a Eucharistic symbol. The foliage of the gazebo, which is relatively accurate in some areas, does not stand up to a comparison with Friedrich's detailed studies of vine leaves. Instead of the squat vine leaves you can see the hop leaves tapering to a point. From a botanical point of view, these are very definitely hop plants, especially since typical hop poles can be seen in the picture center for hop growing in northern Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Image staff

Friedrich's remark “in Brother Adolf's garden” on the preliminary study for the painting and the original ownership of the picture in the family of the Greifswald master's degree Johann Christian Finelius already provide variants for possible interpretations by the picture staff. Paul Ortwin Rave sees in the painting something like a picture greeting card from the painter with greetings to Finelius or to Friedrich's brother Adolf, whereby the persons depicted are supposed to be Friedrich and his wife Caroline. A letter from Caroline Friedrich to her sister-in-law Elisabeth dated December 20, 1818 is used for this purpose.

"... I still remember with pleasure the 17th of August when Magister Finelius came and we sat together in the garden until 10 o'clock ..."

Other interpretations are based on Brother Adolf and wife or Magister Filenius and wife (Helmut Börsch-Supan).

Detlef Stapf sees in the painting one of the memorial pictures for the Neubrandenburg pastor Franz Christian Boll, who died in 1818 and who Friedrich used several times as an image person . This assumption is justified, among other things, with the fact that Boll owned a garden in a hop-growing area outside the city walls of Neubrandenburg and could look from his gazebo exactly in the painted position of his St. Mary's Church , which he wanted a Gothic tower again instead of the existing baroque helmet "im Really Gothic (correct, really Germanic) style ”. Accordingly, Boll and his wife Friederike could be seen in the picture of longing. But the type of man in his compact stature (Börsch-Supan) or, as Werner Hofmann states: “again not portraits, but prototypes” is also noticed. This also means a type of figure that we encounter in the paintings The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog , Chalk Cliffs on Rügen , Auf dem Segler or Two Men Contemplating the Moon .

architecture

In the sketch for the painting, the Greifswald Cathedral St. Nikolai with its baroque tower can be clearly seen behind the roofs. In the painting, only the body of the cathedral is used for an apparently non-existent neo-Gothic church. Analogous to the exchange of people, Friedrich should have meant another church in the painting. Peter Märker interprets the architecture as a political picture content. With regard to the old German costume of the two people, it depends on which ideas the “demagogues” in the foreground have linked with Gothic. The painting shows the Gothic cathedral par excellence, and the individual building becomes the "idea of Gothic". At that time, the Gothic was called the “German style” and served as a projection screen for national identity.

Time of origin

With the exact dating of the painting to the year 1818 and the precisely datable preliminary study, the likely biographical background can be elucidated. Friedrich marries Caroline Bommer on January 21 and is busy setting up the new household for a few weeks. Franz Christian Boll dies on February 12th. Friedrich designed an eight-meter-high memorial for the Neubrandenburg pastor and presented the drawings to the Neubrandenburg city council. At the same time he is working on the plans for the interior of the Stralsund Marienkirche. From June to August Friedrich travels to Neubrandenburg, Greifswald and Rügen to introduce his wife to relatives. On the way he fills out several sketchbooks and creates a watercolor from the Greifswald market . Back in Dresden in September, in what was probably the painter's densest creative phase, he created important paintings such as the Gazebo , The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , Auf dem Segler and the chalk cliffs on Rügen . Since the same type of figure always appears in these works, Detlef Stapf sees them as memory images with which Friedrich reacts to the death of Franz Christian Boll.

Sketches

The drawing in Brother Adolf's garden on August 20, 1818 was used for the painting . This is the case of a drawing, which is rare for Friedrich, as a preliminary study for the painting. In the sketch, in which the internal structure is largely dispensed with, the view that was offered from the garden of Friedrich's brother Adolf is evidently recorded. You can see two female back figures with long dresses, shawls and hats. The silhouette of the St. Nikolai Cathedral in Greifswald rises behind trees and roofs . It is assumed that Friedrich was looking for a picture idea for the planned memorial picture and found it in his brother's garden.

Provenance

Friedrich is said to have given the picture to Johann Christian Finelius from Greifswald. The painting was owned by Hermann Finelius (son of Johann Christian Finelius) in Greifswald until 1848 . The picture was inherited by his sister Friederike Buhtz, was then also in the possession of Paul Hanow (1909–1936 District Court Director, District Court Councilor in Berlin-Spandau) and was lost due to the war in 1944. The drawing in Brother Adolf's garden was ascribed to the Oslo sketchbook and allegedly removed there, acquired in 1928 by the Dresden gallery Kühl and is in the copper engraving cabinet of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden .

Purchase by the Pinakotheks-Verein

The oil painting Gartenlaube was allegedly acquired in 1994 by a young man from an art dealer in Krakow and brought to the consultation hour of the Neue Pinakothek in Munich in a dirty condition. An attribution was initially made difficult by a fantasy signature. In 1995, Friedrich attributed could then gazebo from Pinakotheks Association of the Bavarian State Painting Collections acquired from "private property", according to information provided by the former Director General Johann Georg of Hohenzollern to a "reasonable price". Since then it has been in the collection of the Neue Pinakothek - restored; there the gazebo was presented to the public for the first time 180 years after the ascribed date on July 24, 1998.

Classification in the overall work

The gazebo is the only painting in Friedrich's work in which the pictorial concept as a whole was found in the reality seen and recorded as a sketch. In this way, the creative process can largely be traced up to the changes made. A similar motif, in which the view is framed by an arbor and vegetation, is the burned painting Evening Hour from 1825. Since the painting was in the Neubrandenburg family until 1900, it can also be a representation from the hop gardens.

Garden images of transcendence

The gazebo is the last and most complex painting in a series of garden pictures by the painter. Since the summer painting of 1807 there has always been a new painterly and compositional quality. The garden arbor basically represents the reduction of the arbor triptych from the memory picture for Johann Emanuel Bremer (1817). What these garden pictures have in common is the mediating transcendence of an experienceable present and an unreal distance, separated by a “space barrier” as an element of the garden design. The living or no longer living persons are located in small paradises with the prospect of a world of the non-real. The garden appears as a place of mysterious desires, a symbolic place of romance.

Gothic vision

The gazebo gives the impression of a Gothic building growing out of nature. Friedrich applied this design principle to numerous church motifs, such as the winter landscape with church (1811), the cross in the mountains (1812) and the vision of the Christian church (1812). A political or transcendent religious statement is assumed in the interpretation, such as the symbolic renewal of the church as an institution or the Gothic as the embodiment of a national vision of freedom. If one assumes that the sacred building of the garden arbor is the Gothicized Neubrandenburg Marienkirche, the painting Neubrandenburg can also be seen as a thematic counterpart.

reception

The Rügen pastor Theodor Schwarz wrote the novel Erwin von Steinbach or the spirit of German architecture under the pseudonym Theodor Melas in 1834 . The author provides the fictional character, the cathedral builder Erwin von Steinbach , with a painter named Kaspar, who is close to Caspar David Friedrich in his character and in his biography. Painter and pastor were good friends. In the novel, Kaspar reveals himself as an admirer of Gothic architecture who compares his art with that of the master builder. Erwin von Steinbach had the reputation of being the sole builder of the Strasbourg cathedral .

“As you have given yourselves to noble architecture, you will also possess and keep it like a bride. On the whole I think like you do; my art is above everything to me, and so there is no obstacle that we, if you want, get to know each other better. "

Web links

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné)

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011.

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 .

- Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007.

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006.

Individual evidence

- ^ Paul Ortwin Rave: Caspar David Friedrichs Gartenlaube In: Die Kunst für Alle, 59, 1944, pp. 85–87 (available online)

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 351

- ^ Gerhard Eimer: Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Analyzes and attempts at interpretation. From lectures in Stockholm . Baltic Studies 49, 1962/63, p. 25

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 69

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 146, network-based P-Book

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006, p. 127

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 146, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Franz Boll's handwritten notes taken from Franz Christian Boll . Regional Museum Neubrandenburg V 170 / 2s, sheet 5

- ^ Franz Christian Boll: On the decay and restoration of religiosity. Volume 2, printed by Ferdinand Albanus, Neustrelitz 1810, p. 149

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 112

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 69

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 758

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006, p. 128

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 351

- ^ Paul Ortwin Rave: Caspar David Friedrichs Gartenlaube In: Die Kunst für Alle, 59, 1944, pp. 85–87 (available online)

- ^ Ludwig Grote: Caspar David Friedrich, sketchbook from the years 1806 and 1818 , Berlin 1942

- ↑ Cat. Exh. Caspar David Friedrich the graphic artist, hand drawings and etchings with a foreword by Kurt Karl Eberlein . Heinrich Kühl art exhibition , Dresden 1928

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 758

- ^ Art - Das Kunstmagazin, Hamburg, Issue 10, 1996, p. 12

- ↑ https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artist/caspar-david-friedrich/gartenlaube

- ↑ Bavaria acquired painting from CD Friedrich , Tagesspiegel of No. 15695 of July 26, 1996

- ↑ Back to Runge. New Pinakothek accessible again , Süddeutsche Zeitung from July 11, 1998

- ^ The Alte Pinakothek is about to open, features section , Süddeutsche Zeitung of July 11, 1998, p. 17

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 69

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 398

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 112

- ^ Theodor Schwarz (under the pseudonym Theodor Melas): Erwin von Steinbach or the spirit of German architecture. Hamburg 1834, Volume 1, p. 31