Back figure

The back figure is a subject of painting and graphics, photography and film. It serves to represent the depth of space on a two-dimensional image surface, by means of which the viewer can identify with the figure looking into the image and thus empathize with the spatiality to be conveyed. The back figure has its origin in the art of antiquity and has since been subject to the change in the understanding of images in every art epoch.

function

From the premodern back figure by Giotto to the 18th century, back figures can usually be characterized as repoussoir or mere accessories . As a figure, it is primarily thought of as spatial and is related to other figures or symbolic objects in the picture. A special form of the back figure is occasionally seen in the so-called capricci , where people appear to be taken more from behind than from the front due to the reversal of perspective . As a repoussoir, the modern back figure acts as a mediator in the depth of the picture for the viewer and offers itself as a figure of identification. Up to the Romantic era, the back figure was used with a narrative or compositional justification. In the second half of the 19th century she was the focus of the picture , mainly because of the nude from behind , and solely because of her aesthetic effect. In image semantics , the back view of the person is a vehicle of ambiguity, coded in its culture-specific and historical form.

Painting and graphics

Antiquity

The history of the back figure begins in the archaic epoch of the 6th century BC. The depictions are initially profile figures on wall friezes with the bodies partially turned from the back. From the first perfectly shaped rear view of the human figure, one can see a Greek vase of Euphronios at the end of the 6th century BC. Speak. The first back figures that create a lively, discontinuous depth of space can be seen in the preserved frescoes in the villas of Pompeii . Usually it is naked slaves facing their masters who are placed with the rear view in the foreground. The Alexander mosaic in the Casa del Fauno in Pompeii, dating from the end of the 2nd century BC, is an example of an artistic composition . Was created. Man and horse recorded from different perspectives bring the dynamism into the battle scene. The Greek and Roman-Pompeian painting created an ever more effective physical-mimic and spatial-perspective connection between the individual elements of the motif in order to gain depth in the picture.

At the beginning of the 2nd century AD there was a decline in the spatial character of the picture, the objects and people are increasingly isolated in the surface, losing their plastic substance. The reliefs on the Trajan's Column in Rome are symptomatic of this slow process and represent the first phase of the surface layering of the picture. The proportions of the figures are no longer based on visual experience. The back figure does not disappear with the gradually overcome ancient spatial conception, it retains its pictorial formal meaning, adapts to the changed circumstances, is now mostly built parallel to the surface and only applied to the motif. After the Justinian era in the 6th century and the decline of the arts in Western Rome and Byzantium , the iconoclasm ended this development, as the representation of religious motifs was forbidden for over a century.

middle Ages

The painting of the early Middle Ages reduced space and body equally to the surface. The context of the picture elements expresses religious or secular hierarchies. The back figure is understood as a symbolic sign. In late antiquity , the back figure was still to be derived from the motif and functionally based on parts of the picture; in the Ottonian period it was designed for a uniform space, arising from a conceptual-logical relationship. An ivory relief with the Ascension of Christ from the 9th to 10th centuries exemplifies this substantial unity of figure and space. In the Gothic , the strict two-dimensional connection of the figure is broken by the restoration of a three-dimensional volume. Now the figures and objects are placed in a spatial and temporal relationship in the order of the picture, without giving up the transcendent symbolism of the Romanesque . The Last Supper relief of the rood screen in Naumburg Cathedral offers a three-dimensionally shaped body space in which the hand movement of Judas, sitting with his back on the edge of the picture, acts to conquer space, whereby the circle remains open to the viewer. The blocking of the image by the figure from the back did not occur until the early Trecento at Giotto's Last Supper in the arena chapel of Padua or at the apparition of St. Francis in Arles . Giotto, as a pioneer of the Italian Renaissance , transfers the figure stage of the French-Gothic relief into the surface and thus begins the new painting. The figures seen from the back are now used in the form of a border figure. The being-for-itself of the pictorial event is symbolized, and the viewer is referred to the role of the outsider. Giotto's new formal image quality consists in the dialectical procedure of switching the back figures between art space and real space.

Renaissance

In the early Renaissance, the individual figure in the picture began to be valued as a narrative element, but also with the aim of showing grace and harmony. The sketch work was refined with a better knowledge of anatomy. The painters were interested in mythological subjects in monumental scenes. Portrait painting became more popular and took on naturalistic features. There were first psychologizing picture scenes. This development leads to a greater importance of the back figure, especially for the study of the body and the dynamics of religious picture narration. In fresco painting, the body of the person turned away from the viewer often functions as a pointing figure or acting in the sense of the image impulse. Raffael developed the back figure into a more and more dynamic and dramatic figure by increasingly using gestures to express affects. In the fresco Stanza dell'Incendio di Borgo (1514), for example , the back figures serve to bring the viewer into the picture by conveying important lines of sight and at the same time demonstrating their own experience of the picture. Albrecht Dürer's copper engraving, Four Naked Women (1497), turns the figure from behind into the mysterious center of the naked women who are only connected by looks. Like Leonardo da Vinci , the back figure is used for anatomically precise studies of the human body.

Dutch painting of the 17th century

In Dutch painting of the second half of the 17th century, the back figure gained importance through the need of the bourgeoisie for a new representation of inwardness and privacy in the picture. The painted interiors became a space for a differentiated visualization of the psychic, in which the body could show what is going on in the soul. At the same time, art developed an iconography of gestures and facial expressions that took into account the rules of professional conduct and moral codes. The genre of the love letter reading woman established itself. The back figure was a reflexive compromise between showing and hiding, which the Dutch varied in imaginative facets. An example of a female figure dominating the picture is the painting A Lady in a White Atlas in Front of the Bed with Red Curtains by Gerard Terborch . Although the woman's face cannot be seen, the position of the head suggests that she is reading or pondering something. This happens in a way that stimulates the viewer to speculate, especially because the woman is a quotation from the main character in the painting Fatherly Admonition by the same painter. But it is also cited as a paraphrase of Caspar Netscher after Terborch in the picture The Slippers by Samuel van Hoogstraten , which places the figure from behind in a new context of absence rich in references . The very vivid trompe-l'œil picture entitled Back of a Painting by Cornelis Gijsbrechts shows what economic activity the aesthetic staging of ambiguity in the back of objects brought about at this time .

Allegory of the Art of Painting

Jan Vermeer's painting The Art of Painting turns the back figure of the painter into the reflexive focus of an allegory. The viewer watches the artist painting or how Vermeer paints a portrait and yet cannot see the painter's vision. In the left foreground a chair invites the viewer to take a seat. Allegorical objects are related to the painter sitting at the easel, which also have to do with the process of copying or covering: the plaster mask on the table, the book in the model's hand, the map on the wall or the one to the side thrown curtain, which only seems to reveal the interior. The person shown from behind is the bearer of the communication of this emblematic knowledge presented in a variety of ways, including the perspective rules that are masterfully observed in the picture, which for example place the model in the vanishing point of the picture.

The raft of the Medusa

In French Romanticism , The Raft of Medusa by Théodore Géricault represents the psychological view from the rear. The baroque play of light on the muscular anatomy of the castaways embodies the desperate hope of rescue from distress in the sense of the word. In the artistically built monumentality of a classic pyramid shape, the man waving a tattered flag is compositionally like a figurehead for the will to live in contrast to the dead human bodies lying frontally on the raft. The back figure is here essentially the carrier of the emotionality and symbolism of the image composition.

Caspar David Friedrich

Caspar David Friedrich developed the back figure as the central theme of landscape painting. The romantic painter went beyond their traditional function as a yardstick, compositional element or teaching guide. For him, the figure on the back essentially determines the shape and symbolism of his paintings, watercolors and cuttlefish. It is less about depictions of nature than about constructive compositions with theatrical features. His back figures are the epitome of the romantic notion of subjectivity. In doing so, the painter not only makes a largely open-minded offer of contemplation for the viewer, he actually addresses the open-mindedness; because even the interlinking of the signs in the eye of the observer does not make a total sense. Usually it is figures isolated in the landscape, individually or in small groups, who hold a dialogue with nature without any action. In this relationship between man and nature, the divine universe appears in its transcendental infinity, which Friedrich gives an aperspective and immeasurable spatial quality. Such an attribution of meaning made pictures such as The Monk by the Sea , Woman in Front of the Setting Sun or Two Men Contemplating the Moon into icons of romantic painting. The most famous of these paintings is The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog . Friedrich's back figures have a staffage function or are, for example, memory pictures on which the painter does not want to reveal the identity of the persons depicted.

René Magritte

In modern times, the legacy of Caspar David Friedrich's figures from behind appear not in the numerous popular adaptations with a positive statement of meaning, but rather in René Magritte's meaning-denying surrealist montages . The painter uses the painting La Reproduction interdite from 1937, for example, to interpret the figure from behind in a critical way. By duplicating the rear view in the mirror, he deprives the motif of the logic of the subject-object relationship. While an object, the book lying on the shelf, is actually mirrored, the subject's gaze finds no counterpart. The principle of repetition of the back figures practiced by Friedrich is radicalized again by Magritte. The emotional interpretation of a longing perspective seems just as impossible as a dialogue between foreground and background. Structurally, the picture is in the tradition of the cubist grid motif of Picasso and Braque , but propagates the art picture as a replica in the age of technical reproduction.

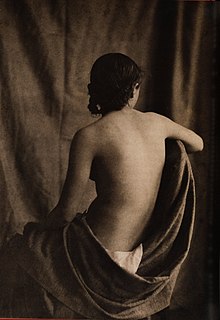

Back act

The back figure in the form of the nude is considered to be the artistic engagement with the curiosity of voyeurism . In the dialectic of showing and hiding, the subjective personality is hidden and, at the same time, intimacy is made visible. With the discovery of the physicality through the art of the Renaissance and the cultivation in the Baroque, the genre of the back nude of painting established itself. The baroque painters play with the possibilities that the eroticized object in particular offers. Velázquez presents a narcissistic beauty with his Venus in front of the mirror , who lets Amor show her face in the mirror. What appears to be a distraction from the body of Venus turns out to be the emphasis on the erotic part of the back, because the facial features are slightly blurred and cannot be seen in detail. It is an etude of self-reflection on painting and its object. On the threshold of the 19th century, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres unfolds with the painting Die Badende von Valpincon that subtle desire with which the invisible exerts a greater attraction on the viewer than what can be seen. In the cool style of classicism, the back figure reveals a previously unknown erotic effect in the context of the suggestive image details, the running bath water as well as the curtain as a metaphor for concealment. Salvador Dalí's double nude from the back, My Naked Woman, looking at her own body, reveals a surreally deconstructed back part in the duplication , which lets the beauty of the object in the eye of the beholder. In the area of drawing, the nude from the back is one of the elementary studies of the body.

Window motif

The window motif in painting is often linked to the figure on the back. The person photographed from behind and looking out of the window conveys the window symbolism for longing, border experience between inside and outside, security and danger, loneliness and the world. Whereby the painting itself is something like a window to a historical world invented or accessible by the painter. Caspar David Friedrich's picture Frau am Fenster shows his wife at the studio window and poplars in the window, as well as a ship passing by the house. Today this motif is considered symbolic of the romantic longing perspective from the inside to the outside world, from the inside to the landscape. The viewer takes part in viewing. The Tischbein watercolor by Goethe on the window of the Roman apartment on the Corso forms a contrast between the dimly quiet room and the noisy street scene that can be suspected. At the same time, this snapshot also allows an intimate encounter with the otherwise dignified poet prince. In Umberto Boccioni's painting The Street Invades House , the frame of the window can be assumed to be transparent or dissolved. The loud and colorful urban scene collapses on the woman on the parapet, is literally absorbed by her. The back figure appears as the medium of a psychological situation of excessive human demands.

Movie

As in painting, the back figures in the feature film correspond tense with the spatial depth of the images. Their function is based on the narrative itself or on the style of the film. The effect of the back view of the protagonists is determined in film history by whether they appear in the context of conventional, modernist or realistic image design. In the image composition of conventional film, the back figure conveys clear information in the sense of narration and dramaturgy, but also serves to harmonize the composition. In typical Hollywood films it is used as staffage, illustrating emotions such as shame, sadness or thoughtfulness ( Fritz Lang Clash by night , USA, 1952). By hiding the identity of people in crime films and the associated feeling of threat and danger, back figures are an effective means of creating tension, as in ( Robert Siodmaks The Spiral Staircase , SA 1945).

In cinematic modernism , the traditional functions of the back figure are complemented by the extended moment of time and the radical departure from the principle of frontality. Jean-Luc Godard's Vivre sa vie (F 1962) shows long shots behind film characters with unorthodox perspectives, unusual cuts and shifted camera angles . This creates an aesthetic of fragmentary and discomfort, with a feeling of alienation.

There are attitudes that neither seem to work completely in the conventional nor in the modernist representation, show a tendency towards the naturalistic. In the film On the Waterfront ( Elia Kazan , USA 1954), which takes place in the milieu of the dock workers, the central figure turns his back on the camera in confrontation with a group of people. Here, social communication is staged by the line-up of the people involved. The film as a study of the milieu is strongly based on the milieu images of 19th century painting. Psychologizing posture of the back piece is a theme in David Wark Griffith strips His Trust (1910 USA), which included watching the protagonist from behind her burning house. In Rosetta by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (B / F 1999) the camera in motion follows the main character running away over long stretches.

photography

Early landscape photography was clearly based on the tradition of painting. Staffage figures, for example in photos of parks, are intended to liven up the picture and direct the viewer's gaze in the desired direction. Around 1900, in picturesque photography, romantically framed landscape sections were created through trees, in front of which strollers photographed from behind watch a sunset and are thus essential conveyors of the mood of the picture. In the genre of romantic landscape photography, the back figure has retained its function of sentimental transfiguration of prospects.

One of the early motifs of the first photographers such as Eugène Durieu was the nude from behind, inspired by motifs from painting. The painter Eugène Delacroix photographed his nude models himself. In surrealist photography, Man Ray decorated the back of his lover Kiki de Montparnasse with two f-holes. The photo went down in the history of photography as one of his most famous works under the title Le violon d'Ingres (1924). This symbolic charging of the back figure helped photography to a certain extent to gain recognition as an art form.

In the social landscapes of the 1960s by Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander and the American Photo-op , the photographer comes into the picture as a figure from behind or as a shadow figure. In Europe, Henri Cartier-Bresson stages the view of three men over the Berlin Wall (1962) in a political picture .

In modern photography, dealing with Caspar David Friedrich's figure from behind is a popular topos . Dan Graham lends his back figures in the View interior. Highway Restaurant, New Jersey (1967) an almost hypnotic reality. The British photographer Alex Boyd has based his series of conceptual and figurative landscape photography entitled Sonnets compositionally on Caspar David Friedrich's back figures, in particular on that of the monk by the sea . He thus addresses the Scottish national identity in Scottish art.

literature

- H. Berstl: The problem of space in early Christian painting . In: Research on the history of forms in art of all times and peoples . IV, Bonn / Leipzig 1920

- Hartmut Böhme : Figures from behind with Caspar David Friedrich . In: Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006

- Herbert von Eine : A forerunner of Friedrich's CD? In: ZDVKW VII, 1940

- Wolfgang Kemp : History of Photography: from Daguerre to Gursky . CHBeck, Munich 2014

- Guido Kirsten: About the figure on the back in the feature film . In: Montage AV, 20.2, 2011 ( Online , PDF)

- Margarete Koch: The figure on the back in the picture. From antiquity to Giotto . Recklinghausen: Bongers 1965, p. 25

- Joseph Leo Koerner: Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape . Yale University Press, 1990, pp. 159-244.

- Hans Jantzen : Giotto and the Gothic style . In: About the Gothic church interior and other articles , 1951

- Jens Christian Jensen : Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999

- Erwin Panofsky : The perspective as a “symbolic form” . In: Fritz Saxl (ed.): Lectures of the Warburg Library . Leipzig - Berlin 1927

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 150, network-based P-Book

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reinhard Steiner: Pièce fugitive . In: Andrea von Hülsen-Esch (ed.): Picture narratives - temporality in pictures . Böhlau, Cologne 2004, p. 154 f.

- ↑ Werner Busch: The graphic genre of the Capriccio - the ultimately futile attempt to control the imagination . In: Ekkehard Mai: The Capriccio as an art principle . Milan 1996, p. 61

- ↑ John Davidson Beazley: Attic Red-figure Vase-painters . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1942, ARV. 101, No. 2

- ↑ John Davidson Beazley: Attic Red-figure Vase-painters . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1942, ARV. 16, No. 4

- ↑ Erwin Panofsky: The perspective as a "symbolic form" . In: Fritz Saxl (ed.): Lectures of the Warburg Library . Leipzig - Berlin 1927, p. 272

- ^ H. Berstl: The problem of space in early Christian painting . In: Research on the history of forms in art of all times and peoples . IV, Bonn / Leipzig 1920, p. 46 u. 51

- ↑ Margarete Koch: The figure on the back in the picture. From antiquity to Giotto . Recklinghausen: Bongers 1965, p. 25

- ↑ Erwin Panofsky: The perspective as a "symbolic form" . In: Lectures of the Warburg Library . Edited by Fritz Saxl. Leipzig - Berlin 1927, p. 276

- ↑ Margarete Koch: The figure on the back in the picture. From antiquity to Giotto . Recklinghausen: Bongers 1965, p. 50

- ^ Hans Jantzen: Giotto and the Gothic style . In: About the Gothic church interior and other articles , 1951, p. 39

- ^ Herbert von Eine: A forerunner CD Friedrichs? In: ZDVKW VII, 1940, p. 157

- ^ Martin Franz Mäntele: The gestures in the painting and drawing work of Raphael. Diss., Tübingen 1999, p. 51

- ↑ Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat: Love Letters. Plea for a new understanding of text and image in Dutch painting of the 17th century . In: 10th Austrian Art Historians Day. Art history and no borders? Art historian. Announcements from the Austrian Association of Art Historians, 15/16 (1999/2000), p. 130

- ↑ Hartmut Böhme: Figures from behind with Caspar David Friedrich . In: Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 103

- ↑ Werner Busch: Caspar David Fruedrich: Aesthetics and Religion. Munich 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 184

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 150, network-based P-Book

- ^ Regine Prange: Open-mindedness and negation of meaning as metapictural principles . In: Verena Krieger, Rachel Mader, Katharina Jesberge (eds.): Ambiguity in art: types and functions of an aesthetic paradigm . Böhlau, Weimar 2009, p. 161 f.

- ↑ Hartmut Böhme: Figures from behind with Caspar David Friedrich . In: Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 67

- ↑ Guido Kirsten: On the back figure in the feature film . montage AV, 20/2/2011, p. 104

- ^ David Bordwell: The Classical Hollywood Style . In: David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin Thompson: The Classical Hollywood Cinema . Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960

- ↑ Siew Hwa Bei: Vivre sa vie . In: Bill Nichols (Ed.): Movies and Methods . Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press, pp. 180-185

- ↑ Guido Kirsten: On the back figure in the feature film . montage AV, 20/2/2011, p. 114

- ↑ Diana Schulze: The photographer in the garden and park: Aspects of historical photographs. Königshausen u. Neumann, Würzburg 2004

- ↑ Wolfgang Kemp: History of Photography: from Daguerre to Gursky . Beck, Munich 2014, p. 86

- ^ Regine Prange: Open-mindedness and negation of meaning as metapictural principles . In: Verena Krieger, Rachel Mader, Katharina Jesberge (eds.): Ambiguity in art: types and functions of an aesthetic paradigm . Böhlau, Weimar 2009, p. 166