Woman at the window

|

| Woman at the window |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1818–1822 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 44.0 x 37.0 cm |

| Old National Gallery Berlin |

Woman at the Window is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, dated between 1818 and 1822 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 44 × 37 cm is in the Berlin National Gallery .

Image description

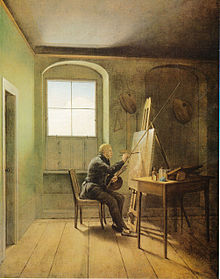

The woman at the window is one of Friedrich's rare paintings in which the natural conditions are depicted with some precision. The painting shows a woman in front of the window of an almost empty room. The viewer sees the wide planks of the floor, bare walls and a window sill with two bottles and a glass on a tray. The room can be identified as Friedrich's studio from the studio picture of Georg Friedrich Kersting from 1811, which was located in house An der Elbe 26.

The woman turns her back on the viewer. She looks deeply out of the window, apparently feeling alone in the room. She wears an ankle-length, pleated green dress with a white frill collar, white stockings and yellowish slippers peek out from underneath. Her hair is pinned together and held in place by a wide comb. The changing green, gray and brown tones of the dress continue in the surroundings of the room. According to contemporary tradition , the figure on the back represents Caroline Friedrich , the painter's wife.

A shop is open in the lower, darkened part of the window and provides a view of the masts and rigging of two sailing boats as well as a row of tall poplars that, according to landscapes from this period, lined the banks of the Elbe. The trees and the passing ship are zoomed in by the painter, the proximity is unrealistic. In the upper window segments a blue sky with a few moving columns of clouds can be seen.

Dating

Since 1916, the date of the woman at the window was 1818, which has been repeatedly confirmed in research. This determination was based on the extensive correspondence of the interior with Friedrich's studio painted by Kersting in 1811 and 1819 , apart from the details. The painter's room was in the Dresden apartment in house An der Elbe 26 (today: Terrassenufer ), which the painter left in 1820 to move to house An der Elbe 33.

Helmut Börsch-Supan concluded from the delayed delivery of the painting to the Dresden Academy exhibition of 1822 that it must have just been completed. The catalog of the Dresden academy exhibition of 1822 noted among the subsequently submitted works: “The artist's Attlier, painted after the nature by Friedrich, member of the academy.” The correspondence of structural details in the compared pictures speaks against the later dating, which is very improbable in the next apartment could also have been present. Nonetheless, dating from 1822 had prevailed since the 1970s. Werner Hofmann recently referred to the fact that the studio was recognizable before 1820.

Provenance

The picture was initially owned by the family, with the exception of the presentation at the Dresden Academy Exhibition in 1822. The Berlin National Gallery acquired the painting in 1906 from Johanna Friedrich in Greifswald, daughter-in-law of Caspar David Friedrich's brother Heinrich. From 1986 to 2001 the picture was in the Gallery of Romanticism in the Knobelsdorff Wing in Charlottenburg Palace . It has been on view in the reopened Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin since 2001 .

Structure and aesthetics

The picture is laid out symmetrically. The middle floor joint and the vertical bar of the window cross mark the central axis. The window niche narrows the barren space depicted. All shapes and lines increase the perception of extreme withdrawnness. The three inclined foot arch joints give the impression of spatial depth, which keeps a space free for the woman, the emphasis on the side frame delimitation narrows this free space for the woman. The resulting architecture creates the spatial character of a dark monastery cell, reinforced by the light contrast of the shimmering yellow-green of the trees and the water-blue of the sky.

The masts and rigging of the two sailing boats form a system of triangles in the window rectangle of the skylight and in the window hatch (in the form of a triptych), creating a geometry of the outside and a geometry of the inside. In addition, the mast of the right boat seems to shift a piece of the image axis to the right, which is brought back into balance by the woman's slight inclination to the left, but visually lets the room sink to the right. The left vertical line of the golden section runs on the inside edge of the frame of the opened middle flap, the right on the middle spar of this flap itself. The narrow transverse spar of the sky window divides it again in relation to the golden ratio.

A finely nuanced aesthetic play of movement emerges in the fixed image architecture. The woman with her soft outlines appears as the only living thing in the strictly designed construction. The viewer of the picture first looks past the woman at the scenery in front of the house and suspects more than he sees. The chamber becomes the dark frame of this view.

Image interpretation

Religious symbol

In Friedrich's work, the sepia view from the artist's window , right window , from 1805/06 is a long motivic lead-in for the painting. For Helmut Börsch-Supan, this results in a religious interpretation in which the window cross refers to Christ. The dark interior stands for the narrowness of the earthly world, which receives its light only through the window as an opening to the unearthly. The opposite bank is seen as the afterlife in the religious sense and the invisible river as death, the boats are ready to cross. The ancient motif of the river of the underworld, which Charon crosses on his boat , is reinterpreted in the Christian sense. The symbol of the longing for death is ascribed to the poplars because of their slimming towards the top.

Image of bondage

For Jens Christian Jensen the sense of the picture results from the shape of the picture. After that, the room has something of a prison room and the woman wants to go out into freedom, which is visible in the rich distance and immensity revealed in the window. The painting is a picture of human longing. Friedrich is assumed to believe that women are not equipped for a free life in the world and that society is not tolerated in such a role.

Spiritual message

According to Werner Hofmann , Friedrich's picture is about the spiritual confrontation of indoor and outdoor space. For this purpose, the sepia window with park area from 1806 bring the motif lead. There the imageless space is contrasted with the lush park landscape. With the woman at the window , part of the view is covered, the viewer suspects more than he sees, like in a "religious window". The shutters in the form of a triptych could be associated with a winged altar. The woman serves as a mediating figure in the picture. Erik Forssman and Hartmut Böhme recognize the old motif of the window as a romantic motif that separates the inner and outer world. As a figure from the back, the woman embodies the thought of longing.

Friedrich's image of women

Detlef Stapf sees one of those pictures in the woman at the window in which the painter assigns Caroline her role in the house and in the family. This was documented even more clearly by images such as Woman ascending to the light or Woman with the candlestick . There are similar images of women with a different message. The garden terrace or the woman in front of the setting sun suggest passion.

Werner Busch speculates that Caroline Friedrich could have become pregnant at this time and that the painter had found an aesthetic expression for this condition. Green and brown in all shades are the colors of creation. In the unfinished painting of Caroline's dress, what is becoming shows itself under the sign of God's creation.

“Much and much has changed since I had a wife. My old, simple domestic furnishings are no longer recognizable in some, and I am glad that things now look cleaner and nicer on me. Only in the room that I use for my occupation does everything stay the same. "

Classification in the complete work

The painting Woman at the Window is unique in this figure in Friedrich's work, but not without a motivic advance under various aspects. In addition to the window motifs with empty interiors with the burned painting Evening Hour, there is another window motif with image personnel. The interior paintings are rare and limited to a few early drawings as well as the few paintings in the later work.

The woman at the window can also be classified in the group of works, in which the views of the landscape are thematized as transitions into other rooms and are to be interpreted as an allegory. These include the gazebo (1818), the cemetery gate (1825/30) and the cemetery entrance (1825). After all, the woman at the window is one of the works with very prominent back figures such as The Wanderer over the Sea of Fog (1818) or the Woman in Front of the Setting Sun (1818).

reception

In an anonymous report on the Dresden art exhibition in the autumn of 1822 it says:

“A small picture, depicting this artist's studio in its peculiar simplicity, with the window in the background with the view of the Elbe and the poplars opposite, would be very true and pretty if Friedrich hadn't just followed his mood again here loves it so much to depict people from behind, his wife is standing in the window like this, in part the lighting and position are very unfavorable, in part he repeats figures that all see each other far too often. "

Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué saw the painting as a genre motif and, after a visit to the painter's studio, wrote a sonnet in 1822 with a compliment to Caroline Friedrich.

Window motif and back figure in art

The image of the woman at the window is now a symbolic motif for the romantic longing perspective from the inside to the outside world, from the inside to the landscape. The viewer takes part in viewing.

The window motif in painting is often linked to the figure on the back. The person photographed from behind and looking out of the window conveys the window symbolism for longing, border experience between inside and outside, security and danger, loneliness and the world. Whereby the painting itself is something like a window to a historical world invented or accessible by the painter.

The motif is seen as an exception in Friedrich's work; suggestions from art history are assumed. The painter may have known Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein's drawing Goethe on the window of the Roman apartment on Corso from 1787, which allows an intimate encounter with the poet prince. Here the dimly quiet room forms a contrast with a noisy street scene that can be suspected. The Woman at the Window (1654) by the Dutchman Jacobus Vrel is also conceivable as a model.

Fritz von Uhde's Girl at the Window (1890) comes closest to Friedrich's wife at the window in composition and pictorial sense .

In Umberto Boccioni's painting The Street Penetrates Into House (1911) the frame of the window can be assumed to be transparent or dissolved. The loud and colorful urban scene collapses on the woman on the parapet, is literally absorbed by her. The back figure appears as the medium of a psychological situation of excessive human demands.

literature

- Hartmut Böhme : Figures from behind with Caspar David Friedrich . In: Giesela Greve (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006

- Helmut Börsch-Supan : The picture design with Caspar David Friedrich. Munich 1960

- Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné)

- Werner Busch : Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Publishing house CH Beck, Munich 2003

- Erik Forssman : Window pictures from romantic to modern . In: Konsthistoriska studier tillägnade Sten Karling , Stockholm 1966, pp. 289-320

- Werner Hofmann : Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0

- Jens Christian Jensen : Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Herrmann Zschoche : Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ PF Schmidt: Caspar David Friedrich. In: Thieme-Becker (Ed.): Allgemeine Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler, XII, 1916, p. 467

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: The picture design with Caspar David Friedrich. Munich 1960, p. 103

- ↑ List of the works exhibited on August 3rd, 1822 ... P. 7, LXXXIIZ

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 110

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 375

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 148

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, p. 128

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 31

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, p. 128

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 149

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 149

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 110

- ↑ Erik Forssman: Window pictures from romanticism to modernity , Stockholm 1966, p. 295

- ↑ Hartmut Böhme: Figures from behind with Caspar David Friedrich . In: Giesela Greve (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 71

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 42 ff., Network-based P-Book

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 32

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006 p. 117

- ↑ Anonymous: About the Dresden art exhibition in autumn 1822. Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 1822, p. 1042

- ↑ Travel memories of Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué and Caroline de la Motte Fouqué, b. v. Briest. 1st part, Dresden 1823, pp. 208 ff.