Hutten's grave

|

| Hutten's grave |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1823 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 73 × 93 cm |

| Classic Foundation Weimar |

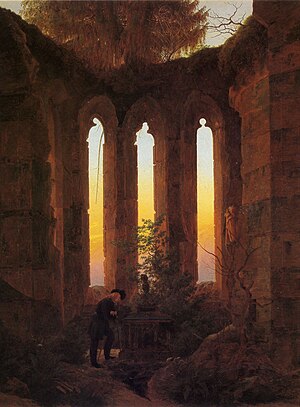

Hutten's grave is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich from 1823 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 93 × 73 cm is in the Weimar art collections of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar , on display in the exhibition of the Castle Museum in the City Palace .

Image description

The painting, held in shades of brown, shows a stone sarcophagus in the ruins of a Gothic choir . On the side of the sarcophagus stands a man in uniform and with an old German beret , leaning on his sword. The walls of the ruin are overgrown by vegetation. White blooming flowers, bushes, and a thistle grow inside the choir, while a withered tree rises up in the foreground on the right. The vault has broken open. A butterfly hovers over the opening. Vis-à-vis the man is a headless white Fides sculpture on a console . The pedestal of the harness on the sarcophagus bears the inscription "Hutten". On the fields of the front sarcophagus wall is written in small letters: " Jahn 1813", " Arndt 1813", " Stein 1813", " Görres 1821", "D ... 1821" and "F. (sic) Scharnhorst ”. The stratification of light in the sky creates a sunset through the choir windows.

Image interpretation

There was never any doubt that Hutten's grave was a political denomination of the painter. The man in the uniform of the Lützow Freikorps at the sarcophagus of the humanist and first imperial knight Ulrich von Hutten and the names Jahn, Stein, Arndt, Scharnhorst and Görres are a largely unencrypted message in the context of the restoration after the Vienna Congress of 1815. Gerhard Eimer recognizes in his Stockholm lectures of 1963 a reference to the persecution of demagogues . According to Peter Märker, "all the traits of the Reformation with which the present identifies." Hutten's grave is also a commemorative picture on the 10th anniversary of the outbreak of the wars of liberation. Jens Christian Jensen here that disclosed in relation to "new German zealots like Ernst Moritz Arndt" Germanness Frederick.

Limited freedoms

Jahn, Stein, Arndt, Scharnhorst and Görres were affected in different ways by the effects of the Karlovy Vary resolutions . Friedrich Ludwig Jahn was arrested in 1819 and was held in custody until 1823. Prussia banned gymnastics. In 1819, the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn suspended Ernst Moritz Arndt from his teaching post as professor of history because of “demagogic activities”. The plans of Freiherr von Stein for a Prussian-Austrian dominated federation state found no support from the relevant princes and politicians.

Joseph Görres escaped arrest in Prussia in 1819 by fleeing to Strasbourg ; his newspaper Rheinischer Merkur was banned in Prussia as early as 1816. General Gerhard von Scharnhorst , who died in the war in 1813 , was forgotten as the most exemplary of the military reformers of the time of the Wars of Liberation. All of the persons listed are in the Hutten tradition as “fighters for freedom of the spirit”. The publisher Georg Andreas Reimer was forbidden by the censors in 1822 to reissue Hutten's works.

Hutten's grave was exhibited in Berlin and Hamburg in 1826 with the note that the proceeds from the sale were intended for “those in need of the Greek struggle for freedom”.

Missing monuments

The painting is clearly interpreted by Helmut Börsch-Supan as a memorial that alludes to the political situation in 1823. Otto Schmitt sees a reference to the 300th anniversary of Ulrich von Hutten's death, which was commemorated this year. A grave monument to his grave on the island of Ufenau in Lake Zurich in front of the chapel of St. Udalricus "... seems to have failed the great German man" complained the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung . Because of the formative influence of Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld on Friedrich's work, Detlef Stapf suspects that the Kiel professor's “Theory of Garden Art” was a decisive stimulus. Hirschfeld saw the time had come, instead of setting up "repeated copies of the deities of antiquity" in the princely gardens, "to dedicate part of this effort to the true benefactors of the human race and the deserving men of our own nation!" "Decreed that he should" set monuments in honor of our most deserving men ", which should also apply to the heroes who are still alive:

“But we mustn't always wait to weep for monuments to our deserving husbands; we can dedicate it to them, when their fame is decided, in their lifetime. "

A letter to Ernst Moritz Arndt on March 12, 1814 shows that Friedrich pursued a memorial concept:

“Dear compatriot! I have received your dear letter and the drawings that came with it. I am in no way surprised that no monuments are erected, neither those that describe the great cause of the people, nor the generous deeds of individual German men. As long as we remain servants, nothing great will ever happen. Where the people have no voice, the people are not allowed to feel or to honor themselves. I am now occupied with a picture where a monument has been erected in the open space of an imaginary city. I wanted to designate this monument for the noble Scharnhorst and ask you to make an inscription. But this inscription shouldn't be much longer than twenty words, because otherwise I won't have enough space. I expect your kindness to grant my request. Your compatriot Friedrich. "

It is also undisputed that Friedrich portrays a contemporary who is still alive in the painting. The reviewer of the literary conversation paper wants to recognize Friedrich himself in his review of the Dresden exhibition of 1824. Helmut Börsch-Supan suspects Joseph Görres to be in the figure. Detlef Stapf finds in the Neubrandenburg theologian August Milarch the person from Friedrich's environment who can withstand a comparison of images and who fits a suitable biography in terms of the picture narration.

August Milarch

August Milarch was a relative of Friedrich. In Neubrandenburg, where he was vice principal at the school of scholars, he was considered a hero of the wars of liberation . In 1813 the theologian had volunteered with his entire prima for the patriotic regiment of the Strelitz C-Hussars to go to war against Napoleon . Milarch fought in the Battle of Leipzig as a lieutenant in York Corps. In 1814 the officer traveled in the entourage of Prince Blücher to the celebrations of the victory of the Allied troops over Napoleon in London and represented the hussar regiment of the Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. For his services at the Battle of Leipzig, Milarch received the Russian Order of St. Vladimir 4th class with the ribbon and the Iron Cross .

Milarch can be associated with the names on the sarcophagus in each individual case. He was Friedrich Ludwig Jahn's successor as private tutor in the house of Baron Friedrich Heinrich von Le Fort in Neubrandenburg and continued Jahn's native gymnastics there. With Joseph Görres connected him beyond the war, the journalistic work on Philipp Otto Runge's work times .

When Friedrich began work on Hutten's grave , Milarch, like Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, was affected by the prohibition of the Turner movement.

Judging by the lines of the sketch for the painting, Friedrich portrayed Milarch standing as a model with the help of a camera obscura . The later pastor in Schönbeck had himself photographed in 1859, making him the only figure in Friedrich's picture staff who has a photo.

Fides sculpture

The Fides sculpture on the console is related to the man on the sarcophagus. The representation of St. Fides without a head acts as a powerful symbol here. The martyr , a 13-year-old girl who refused to worship pagan gods during the persecution of Christians under Emperor Maximinus , was beheaded in 303. With the name (Fides = loyalty), the Christians in Rome also referred to the tradition of the Roman religion, to see in Fides the personification of trust, loyalty and the oath in the obligation of the state. The names Milarch, Jahn, Arndt, Stein, Görres and Scharnhorst could be gathered here under the Fides figure to lament the betrayal of their ideals in the Restoration.

Butterfly as a soul symbol

The butterfly has a high status in Friedrich's symbol hierarchy. The butterfly can be found in those subjects in which the painter can be assumed to have a great deal of inner involvement in the picture. The fact that it is used as a Christian resurrection symbol can be deduced from the lost sepia drawing My Burial (1803/1804), because the butterflies there are depicted as Friedrich's own soul as well as that of the deceased mother and siblings. The butterfly motif can also be found in the woodcuts woman with spider web between bare trees and boy sleeping on a grave (supposed to show his brother Christoffer who drowned in 1787), on the column of the Neubrandenburg monument to Franz Christian Boll and in the drawing Grasses and Palette (1838) , as a "farewell to life and art". The butterfly in the picture structure of Hutten's grave indicates that "patriotic things" are just as important to the painter as family and his own existence.

Representation of nature

In the representation of nature, a nature-religious interpretation predominates. For Helmut Börsch-Supan, plants that grow out of the rubble are symbols of the new piety of nature, the spruce stands for believing Christians, the thistle for pain, and the flowers as the promise of resurrection. Peter Märker advocates seeing nature that has outgrown the ruins as a symbol of future religiosity , an analogy to the historical process in the natural processes of growth, decay and reblooming. Detlef Stapf explains the iconography of the plants at the level of the painter's color symbolism, for example with white flowers as a symbol of loyalty, but gives the recommendations for image composition according to Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld for the use of vegetation in the ruins.

“The connection or interruption of the ruins with grass, bushes and individual trees helps to give them a natural look even more. Nature seems to reassign itself the places that architecture had stolen from it with a kind of triumph as soon as they, abandoned by the inhabitant, become deserted. [...] - all these changes [...] very vividly herald the power of time, and at the same time are accessories and decorations of the ruins that art creates. "

Sketches

The drawing of the ruined monastery on the Oybin, July 4th 1810, is used for the Gothic choir . This is the "interior of the famous church ruins of Oybin bei Zittau ", more precisely the sacristy of the monastery church. The thistle on the left in the painting comes from the drawing Distel and two tree studies, 17th / 24th. July 1799 . The sheet of study on 'Hutten's Grave' , dated around 1824, shows the drawing of the warrior and the figure of Fides. The knight's helmet on the sarcophagus can be found in the draft for a war memorial with a knight's helmet and sword made around 1824 .

Provenance

The painting Hutten's grave was shown for the first time in 1824 at the Dresden art exhibition and bought in 1826 by Duke Karl August von Sachsen-Weimar . After the last Grand Duke abdicated, the work was transferred to the Weimar art collections in 1919 , since 2003 the art collection of the Weimar Classic Foundation , which is showing it in the exhibition of the Castle Museum in the City Palace .

Classification in the overall work

Hutten's grave is the one with the clearest political message in Friedrich's work. Ten years after the war of liberation, the painter also sees himself cheated out of his ideals of freedom by the restoration and prompted to make a clear statement through his art. In order to equip his friend, the painter Georg Friedrich Kersting in 1813 for the service of the Lützow hunters , Friedrich got into existential debt and wrote to his brother Heinrich:

“The cause of my present significant debt is 300 thalers. amount is not unknown to you; I do not regret it at all, on the contrary it serves to calm me down. "

Patriotic motives

Hutten's grave is the last painting by Friedrich made between 1812 and 1823 with a recognizable or transmitted patriotic motif. The tombs of old heroes (1812) are the first picture in which the concept of “painted” monuments is implemented. There is a reference to the war of liberation against Napoleon under the titles Cave with Tomb (around 1813/14) and Der Chasseur im Walde (1814). In connection with the painting Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819), Karl August Förster's memoirs conveyed the painter's declaration: “They do demagogic activities”.

Ruin pictures

The church ruins of the Oybin monastery near Zittau in Saxony are seldom to be found in the important pictures of Friedrich compared to the Greifswald ruins of the Eldena monastery . The use in the painting Hutten's grave probably primarily follows the image architecture developed from the image idea. Here, however, the painter's concept of making the Gothic choir the site of historical or religious events was ideally implemented in the symmetrical structure of the picture and forms the end point of a development of the subject. The later Greifswald drawing Jakobikirche as a ruin (1817) offers a range of shapes similar to that of the Oybiner choir. The painting Ruine Oybin (1812) with a Madonna figure can be seen as a preliminary stage for Hutten's grave , for which the narrative theme has not yet been found.

The abbey in the oak forest (1809) stands in an expansive landscape and shows little focus on the interior of the choir. The large picture Klosterfriedhof im Schnee (1819) or Der Winter (1808) already show a greater concentration on the central architecture. Another example of the vegetable reshaping of a crumbling Gothic choir is the painting Ruine Eldena from 1825. The ruin Eldena in the Giant Mountains (1834) uses the Gothic choir as a subordinate landscape element.

As Friedrich himself comments on one of his pictures of ruins, the text on the lost painting The Cathedral of Meissen as a Ruin (around 1835) reveals :

“One word gives the other, as the saying goes, one story gives the other and thus one picture gives the other. Now I'm working on a large painting again, the largest I've ever done: 3 ½ inches high and 2 ½ inches wide. Like the picture mentioned in my last letter, it also depicts the interior of a crumbling church. I based the beautiful, still existing and well-preserved cathedral at Meissen as a basis. The mighty pillars with slender, graceful columns protrude from the high rubble that fills the inner room, and in part they support the high arching. The time of the glory of the temple and its servants has passed and a different time and a different desire for clarity and truth have arisen from the shattered whole. Tall, slim ever green spruce trees have outgrown the rubble; and standing on rotten images of saints, destroyed altars and broken holy kettles, with the Bible in his left hand and the right on his heart, leaning against the remains of an episcopal memorial, an evangelical clergyman with his eyes fixed on the blue sky, contemplating the light, light clouds [deleted afterwards:] like a flock on a green meadow. "

See also

Another patriotic adaptation is the poem Hutten's Last Days .

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné).

- Gerhard Eimer : Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Analyzes and attempts at interpretation. From lectures in Stockholm. Baltic Studies 49, 1962/63.

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011.

- Günther Grundmann: The Riesengebirge in Romantic Painting , 2. Erw. Ed., Munich 1958

- Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben und Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785, Volume 3.

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 .

- Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1999.

- Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007.

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book .

- Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings, Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 398.

- ^ Gerhard Eimer: Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Analyzes and attempts at interpretation. From lectures in Stockholm . Baltic Studies 49, 1962/63, pp. 39–68.

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007 p. 64.

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 98.

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1999, p. 103.

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007 p. 64.

- ↑ letters Reimers to Niebuhr from 04.13.1822 . In: Prussian year books, Volume 38, 1876, p. 66.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 389.

- ↑ Otto Schmitt: The Eldena ruins in the work of Caspar David Friedrich . Art letter No. 25, Berlin 1944.

- ↑ Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung . Year 1823, p. 552.

- ^ Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben and Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785, Volume 3, p. 141 f.

- ^ Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben and Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785, Volume 3, p. 131 f.

- ^ Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben and Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785, Volume 3, p. 149.

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006, p. 86 f.

- ^ Literarisches Conversationsblatt 1824, p. 59.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 389.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 155, network-based P-Book .

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 159, network-based P-Book .

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 83, network-based P-Book .

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 278.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 45.

- ↑ Philipp Otto Runge: Legacy writings . Published by his eldest brother. Volume 1, Hamburg 1840, p. 310.

- ^ Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 64 f.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 262, network-based P-Book .

- ^ Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theory of garden art . Five volumes, MG Weidmanns Erben and Reich, Leipzig 1797 to 1785, Volume 3, p. 112.

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 587.

- ↑ Günther Grundmann: The Riesengebirge in the painting of the Romantic period , 2nd exp. Ed., Munich 1958, p. 71.

- ↑ Karl-Ludwig Hoch: Caspar David Friedrich and the Bohemian Mountains , Dresden 1987, p. 139, note 341.

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 151.

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 790.

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 831.

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006, p. 91 f.

- ^ Karl Ludwig Hoch: Caspar David Friedrich, Ernst Moritz Arndt and the so-called demagogue persecution . In: Pantheon 44, 1986 p. 74.

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work. 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 706.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 324.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 351.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 396.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 441.

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich. The letters. ConferencePoint Verlag, Hamburg 2006, p. 215.