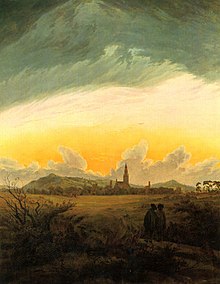

The burning Neubrandenburg

|

| The burning Neubrandenburg |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1830–35 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 72.2 × 101.3 cm |

| Hamburger Kunsthalle |

The burning Neubrandenburg , also sunrise at Neubrandenburg or sunset at Neubrandenburg , is an unfinished painting by Caspar David Friedrich, dated between 1830 and 1835 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 72.2 cm x 101.3 cm is in the Hamburger Kunsthalle .

Image description

The painting shows a path between harvested fields that leads to the gate of a Gothic city. The title of the picture describes the city as Neubrandenburg . The city is surrounded by a ring of trees that is open to the left and offers a view of a three-part gate system. A church and two other buildings protrude above the tree height. The church has a richly decorated gable, the tower is flattened after two floors. In the front left are three haystacks. Boulders or boulders line the path. The church dominates the silhouette of the city. The roof of the church is covered in one place, white and brown clouds of smoke drift outside. The smoke combines with the gray-blue chain of clouds in the background. Rays of the sun hidden behind the city break out of the clouds. At the top, the light blue sky turns into a monochrome light gray.

Image and nature

The situation of the landscape before 1830 is recorded by the free grassland, called "The Heiden", extending north behind the city wall, and the exact location of the Friedlander Tor in the north of the city . This is evidenced by a map of Neubrandenburg from 1820 and a drawing (1819) by Carl Gustav Carus with a view of the city from the north. The layout of the path that leads to Friedländer Tor also corresponds to the conditions at the beginning of the 19th century. The Marienkirche is shown in relation to the Friedländer Tor in the main axis with a slight counter-clockwise rotation. The perspective depends on whether you want to focus on the real topographical situation of the Friedländer Tor or that of the Marienkirche. However, the painter's view of St. Mary's Church as shown is only possible from the northeast. It is the city panorama that came to Friedrich von Greifswald from Neubrandenburg. In art historical literature, the view from the east is usually given. The painter has given the tower of St. Mary's Church, which until 1842 had a baroque hood, in the picture over two floors with an octagonal shape without a point. To the right of the Marienkirche you can see the Treptower Tor and the Mönchen-Turm at the end of Darrenstrasse. The earth wall on the left and the group of trees outside the oak-covered ramparts represent the boundaries of the cemetery outside the city, which was then just created. A loose tree population, as can be seen on the right on the horizon, actually delimited the extensive grassland. Friedrich's interest in the compositional effect of the large open meadow area in front of the city gate is shown by the sepia church ruins in a meadow landscape , which shows the view from the opposite side of the Zingel of the Friedländer Tor.

Structure and aesthetics

The layout of the picture is based on an acute-angled geometry. The path through the fields leads through two thirds of the deep foreground directly to the city gate. This diagonal is answered by a line that rises from the low gate of the entrance gate to the top of the tower. This right-weighted image division is absorbed by the positioning of the five rays of the sun as a symmetrical figure in the center of the image, emphasized by a depression in the cloud bank. Below the rising line the view opened into the pale color distance, while the groups of trees on the left counteract with a strong interior drawing. The foreground reflects these shape and tone relationships in the confrontation of the soft contours of the haystack and the angular boulders. The landscape is kept in shades of brown, which are streaky interrupted by green, yellow and gray. Since the picture remained unfinished, probably because of Friedrich's health restrictions, one can only speculate about the final color design. In the horizontal stratification, one behind the other and one above the other are closely intertwined. The unfinished state of the picture gives an insight into the painting style.

Image interpretation

The painting is interpreted religiously as well as from the historical and architectural-historical context. Helmut Börsch-Supan sees the burning Neubrandenburg as a symbol of salvation history. The way means the way of life, the haystack the rapid transience of life, the boulders symbolize faith, the city stands for the place where the soul lives after death, the city gate represents the entrance to the realm of the dead. The burning church is a parable for the Last Judgment. Wolfgang Braungart locates the image motif in the iconography of the apocalypse of modern literature and art. Since the burning church is probably not based on a historical event, the fire is Friedrich's apocalyptic invention. Gerhard Eimer determines the sense of the image via the surface-binding radiation motif, which Friedrich theologically explains for the Tetschen Altar , as a vision of fate both in personal and general viewing. He recognizes an expression of pessimism on the future of the idea of Gothic. Friedrich Scheven thinks it is possible that Friedrich used the great city fires of 1614, 1676 and 1737 in the painting as a symbol of the transience of everything earthly. Eckhard Unger reads the picture as a parable of three sets, for the setting of the city due to city fires, the setting of the day with the setting of the sun and the setting of the year with autumn.

Detlef Stapf interprets the painting as an image of outrage and places it in connection with the neo-Gothic renovation of the Marienkirche in Neubrandenburg. According to the plans submitted by the architect Friedrich Wilhelm Buttel in 1829 , the tower of the Marienkirche was to be executed on an octagonal floor plan without a point, based on the model of Karl Friedrich Schinkel's Friedrichswerder Church in Berlin , as shown in the painting. After protests by the citizens of Neubrandenburg and the intervention of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Grand Duke , a pointed tower was finally built. Friedrich also saw in this architectural variant, as documented in the painting Neubrandenburg , the actual Gothic ideal. The conflict over the tower architecture could be the reason for the motif of the burning city, the two Neubrandenburg pictures architectural thesis and antithesis. Erich Unger suspects that Buttel had a direct stimulus for the motif, but this has not been proven. Friedrich could also have implemented a metaphor from the pastor of the Marienkirche, Franz Christian Boll , who saw the Gothic architecture as a vision of the future.

“Perhaps this new, better time has already begun quietly; individual rays of light break out and point to a new day for mankind; what believing mind could fear that the terrible struggle of our day will end with the general annihilation of all that is good and glorious? "

In Werner Hofmann's view, Friedrich's cityscapes are “material for poetic paraphrases whose place is nowhere”. Gertrud Fiege interprets the fire in the city skyline as well as the depiction of the Meissen Cathedral as a ruin as overcoming the past.

Sun position

In art historical literature it is disputed whether the painting depicts a sunrise or a sunset. The question cannot be answered topographically, because the center of the fan of rays would have to be located more to the south than to the west and would therefore result in a high position of the sun. It is not known whether the title, View of the City of Neubrandenburg at Sunset and a Conflagration, given in the estate directory corresponds to the painter's intention. The term sunset has established itself because of the topographical orientation ( Ernst Sigismund , Gerhard Eimer, Sigrid Hinz, Werner Sumowski). For reasons of religious interpretation, Helmut Börsch-Supan insists on a sunrise, because he sees in the fire a parable for the Last Judgment and the rising sun heralds the dawn of Judgment Day. Detlef Stapf creates a connection between religious interpretation and topography. If you follow the thesis that the Tetschen Altar was designed for the church of Hohenzieritz , then the sun fan as a sunset in the topography would have its origin right there and symbolize the continued existence of the indestructible teaching of Jesus. The rays of the sun laid out as fanned out segments can also be found in the painting Woman in front of the setting sun , just as the path there is lined with boulders. The position of the sun is relevant for the designation of the image. In the catalog raisonné, the painting is listed as sunrise near Neubrandenburg , while the picture is shown in the Hamburger Kunsthalle under the title The Burning Neubrandenburg .

Biographical place

Caspar David Friedrich's parents, Adolph Gottlieb Friedrich and Sophie Dorothe Bechly, were born in Neubrandenburg. In addition to extensive relatives, his brother Johann Samuel lived there as a blacksmith in 1815 and his sister Catharina Dorothea outside the city gates in Breesen . Friedrich stayed in Neubrandenburg again and again from his childhood until the end of 1818. A large part of the work relates to the area of the Tollensee lake in front of the city . The painter had a special relationship with the pastor of the Marienkirche, Franz Christian Boll, who is depicted several times in the painter's pictures. If there was no post from Neubrandenburg to Dresden, Friedrich was disappointed, as he confided in his Loschwitz diary on August 5, 1803.

"I can't understand how it may come about that I don't receive any letters from [New] Brandenburg."

Sketches

For the path and foreground of the painting, Friedrich used the small-format watercolor Landstrasse in Ebene mit Bergen from October 1824 (Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden). The picture probably shows a landscape in the vicinity of Dresden .

Provenance

The painting was in Friedrich's estate directory in 1843 under number 1 with the title View of the city of Neubrandenburg at sunset and a conflagration . The Kunsthalle Hamburg acquired the picture in 1905. The director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle Alfred Lichtwark discovered the painting from Harald Friedrich's mother , a grandson of Caspar David, in Dresden under the name The Hay Harvest . The woman had relatives reproduce it because they did not appreciate the picture. After the immediate restoration, Lichtwark realized that the silhouette was that of Neubrandenburg and reported on the discovery of the commission for the administration of the Kunsthalle.

"Friedrich has got a completely different face [...] Everything has become light and clear, the delicate green, brown and violet in the foreground, the mother-of-pearl of the morning sky [...]"

Dating

The dating could not be determined exactly until today. The first dating by Max Sauerlandt was from 1832. A dating to the 1820s by Herbert von Eine could not prevail. The assumption that the painter could not have finished the work as a result of his stroke led to a matching date of 1835 by Charlotte M. de Prybram-Gladona, Gerhard Eimer Helmut Börsch-Supan . and Willi Geismeier Detlef Stapf has taken up a date from around 1830 by Sigrid Hinz and Erich Brückner. If it were a statement by Friedrich on the plans of the architect Buttel from 1829, so the argumentation, the painter's indignation would have been translated into a picture in a timely manner.

Counterpart

According to Peter Rautmann, Friedrich designed the paintings The Burning Neubrandenburg and Rest at the Hay Harvest as counterparts. The three-zone structure of the pictures is comparable. The rural area is contrasted with Gothic architecture and the architectural area is backed by a clear sky with a band of clouds over the horizon. The rest at the hay harvest shows the ruins of Landskron north of Neubrandenburg .

anecdote

In his historical-topographical sketches from the prehistory of the Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg , published in 1876 , the Neubrandenburg mayor Wilhelm Karl Georg Ahlers reports anecdotally about the creation of the painting.

“The famous landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich, who stayed here often and for a long time, and especially in the years from 1820-1830 with relatives, was working on the completion of a picture of our beautiful city and its charming surroundings that he had already begun from Datzeberg taken up, prevented by the fact that, while he was busy at work, the corpse of a drowned man was pulled out from under his eyes from the datze that washed around the foot of the hill. At this sight he was put in such a gloomy mood that he broke off from work and was not able to take it up again later either. Anyone who has seen one or the other of the effective pictures by this outstanding master will regret that that sad accident had such consequences and that the unfinished picture did not remain here either. "

Classification in the overall work

The burning Neubrandenburg is one of the enigmatic pictures of the late work. Presumably an illness prevented the painter from completing the painting, so that it can also be seen as a document of the limited possibilities in artistic production at an advanced age.

Neubrandenburg views

The burning Neubrandenburg can be seen as an antithesis to the transfiguring image of Neubrandenburg , which shows the city from a comparable perspective. There is no other city with which Friedrich maintains such an emotional relationship in his art. The Gothic Marienkirche appears as the actual motif in the city silhouette with the different architectural variants. The transparent painting with the title Mountainous River Landscape in the Morning and at Night can also be assigned to the period between 1830 and 1835 . The banner is painted on both sides. To view the night scene, the image must be backlit. Because of the double island shown in the foreground, which existed around 1800 between the southern end of the Tollensee and the Lieps , one can interpret the Gothic city silhouette at the end of the valley as the Neubrandenburg. Here the transfigured moment is heightened again by the fantasy architecture and the mood of the picture and confirms the painter's emotional attitude towards this place.

According to Detlef Stapf, only the Marienkirche in a further architectural variant shows the painting Gartenlaube , which also offers a view from outside the city walls of Neubrandenburg.

City images

In Friedrich's city pictures, the city silhouettes have different functions in the picture narration. Views emerged from the biographical locations that reveal an inner relationship between the painter and the respective city. The representations of Greifswald show a vedute-like clarity. Neubrandenburg appears transfigured or burning. Dresden is preferably placed behind a hill or a wooden fence in the picture compositions . Usually one can assume that these pictures are true to nature.

A second group of pictures shows dreamy fantasy cities in the deep space, as in the paintings Gedächtnisbild für Johann Emanuel Bremer or Auf dem Segler .

A third group places figures in the foreground in a symbolic relationship to a city in the background, as in the painting The Sisters on the Söller at the harbor . In this case, identifiable picture elements can be used to assign a real city.

Ideal of the Gothic city

For the Neubrandenburg depictions of Friedrich, the medieval city on a river by Karl Friedrich Schinkel , created in 1815, is used in an art-historical comparison . In all of these pictures the high Gothic sacred building is the defining element of the city. After the victory over Napoleon, a national interpretation is obvious, because the Gothic was called the “German style” at that time and served as a projection screen for national identity. But the Romantics also idealized the medieval city with the Gothic cathedral buildings . Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder discovered the picturesque beauty of Nuremberg with the description of St. Peter's Church. The painter Carl Wilhelm Götzloff , captured by his enthusiasm for Gothic, composed his winter landscape with a Gothic church from 1821 based on the model of his teacher Caspar David Friedrich. In a review of the picture it was said: "Like this [Friedrich] he seems to be fleeing beautiful leafy trees, clinging to coniferous wood, snowstorms, churchyard, moonlight, etc. ..." He was "a great friend of German bustle, and spoke to himself in his previous year's landscape completely as such. "

reception

Ernst Boll , theologian and scientist, attributed the painting with the burning city, which from the point of view of his contemporaries was unsuccessful, to the difficulty of portraying Neubrandenburg in a suitable way in the scenic panorama, "whose total impression is poignant". Boll, however, was only known to Friedrich's view of the city, The Burning Neubrandenburg .

“But the painter's art also fails because of this panorama; for it is too big for a single picture, and if one wants to represent it only in part, the main effect, which is produced by the harmonious cooperation of all individual parts of this landscape, is completely lost. As painterly as the whole thing is, not a single picture suitable for painting can be cut out of it, and all attempts made in this regard have completely failed. [...] As beautiful as it [the city] appears to the eye from all sides, an effective picture of it cannot be drawn from a single point in the vicinity, since there is no suitable foreground everywhere. [...] Like few other painters, [Friedrich] knew how to design highly impressive pictures from standpoints that were peculiar and even usually considered detrimental to the effect. Perhaps, therefore, he would have succeeded in solving a task on which other draftsmen and painters have failed. "

In the art-historical view of Friedrich's painting The Burning Neubrandenburg , in the romanticism of William Turner in 1835, The Fire of the Parliament Building in London and The Fire of the Upper and Lower Houses are seen as comparable, since they also have burning Gothic architecture as their motif. John Constables Cathedral in Salisbury from 1834, with its dramatically clouded church architecture, is just as emotional an expression of the painter as The Burning Neubrandenburg .

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné)

- Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008

- Gerhard Eimer: Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Analyzes and attempts at interpretation. From the Stockholm lectures . Baltic Studies 49, 1962/63

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011

- Werner Hofmann (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840. Exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, September 14th to November 3rd, 1974 . Art around 1800. p. 296 f.

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0

- Helmut R. Leppien: Caspar David Friedrich in the Hamburger Kunsthalle . Stuttgart 1993

- Peter Rautmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Landscape as a symbol of a developed bourgeois appropriation of reality. Peter Lang Verlag, Bern 1979

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Eckhard Unger: Downfall in Neubrandenburg. Interpretation of the painting by Caspar David Friedrich in Hamburg . In: Das Carolinum 26, 1960, pp. 108–111

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner Hofmann (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840. Exhibition in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, September 14th to November 3rd, 1974. Art around 1800 . P. 297

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 16, network-based P-Book

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008, p. 153

- ^ Gerhard Eimer: Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Stockholm lectures . Verlag Christoph von der Ropp, Hamburg 1963, p. 37

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008, p. 153

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings . Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 448

- ↑ Wolfgang Braungart: Apocalypse and Utopia . In: Gerhard R. Kaiser: Poetry of the Apocalypse . Königshausen u. Neumann, 1991, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840. Exhibition in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, September 14th to November 3rd, 1974. Art around 1800 . P. 296 f.

- ^ Gerhard Eimer: Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Stockholm lectures . Verlag Christoph von der Ropp, Hamburg 1963, p. 37

- ^ Friedrich Scheven: Two city views of Mecklenburg romantics. In: Carolinum 32, vol. 45, 16

- ^ Eckhard Unger: Downfall in Neubrandenburg. Interpretation of the painting by Caspar David Friedrich in Hamburg. In: The Carolinum. Leaves for culture and home. No. 32, 26th year, Göttingen 1960, p. 108 f.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 217 f., Network-based P-Book

- ↑ Erich Brückner: CD Friedrichs Sunset . Carolinum 27, 1961, p. 109 f.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 221, network-based P-Book

- ^ Franz Christian Boll: On the decay and restoration of religiosity . Volume 2, printed by Ferdinand Albanus, Neustrelitz 1810, p. 10

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 114

- ^ Gertrud Fiege: Caspar David Friedrich in personal reports and documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1977, p. 101

- ^ Ernst Sigismund : Caspar David Friedrich. An outline drawing . Dresden 1943, p. 123

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 221, network-based P-Book

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 448

- ^ Helmut R. Leppien: Caspar David Friedrich in the Hamburger Kunsthalle . Stuttgart 1993, p. 42

- ^ Karl Ludwig Hoch: Caspar David Friedrich - unknown documents of his life . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1985, p. 26

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 782 f.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840. Exhibition in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, September 14th to November 3rd, 1974. Art around 1800 . P. 296 f.

- ^ Alfred Lichtwark: Letters to the commission for the administration of the art gallery . Hamburg 1908, p. 31 ff.

- ↑ Max Sauerlandt: The quiet garden. German painter of the first half of the 19th century . Koenigstein i. T., 1908, 2nd ed. 1909, p. 32

- ^ Herbert von Eine: Caspar David Friedrich. Berlin 1938. Wassily Andrejewitsch Joukowski and CD Friedrich. The work of the artist I , 1939, p. 94

- ↑ Charlotte M. de Prybram-Gladona: Caspar David Friedrich. Paris 1942, p. 79

- ^ Gerhard Eimer: Caspar David Friedrich and the Gothic. Stockholm lectures . Verlag Christoph von der Ropp, Hamburg 1963, p. 37

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 427

- ↑ Willi Geismeier: On the importance and developmental position of a feeling for nature and landscape representation in Caspar David Friedrich. Dissertation, Berlin 1966, p. 57

- ^ Sigrid Hinz: Caspar David Friedrich as a draftsman. A contribution to the stylistic development and its importance for the dating of the paintings . Diss. Greifswald 1966 (Ms.), p. 78

- ↑ Erich Brückner: CD Friedrichs Sunset . Carolinum 27, 1961, p. 109

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 426.

- ^ Peter Rautmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Landscape as a symbol of a developed bourgeois appropriation of reality . Peter Lang Verlag, Bern 1979, p. 105

- ^ Wilhelm Karl Georg Ahlers: Historical-topographical sketches from the prehistory of the Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg. Publisher by E. Brünslow, Neubrandenburg, 1876, p. 107

- ^ Franz Boll: Chronicle of the Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg . Neubrandenburg, 1875, p. 279

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 4, network-based P-Book .

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 5, network-based P-Book .

- ↑ Gerhart von Graevenitz (ed.): The city in European romanticism . Publishing house Königshausen u. Neumann, 2000, p. 96.

- ^ Friedrich Matthäi in a letter dated December 9, 1822 to Count Vitzthum von Eckstädt

- ↑ Enst Boll: Description of the Tollense. A contribution to patriotism. Archive for regional studies in the Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg and Revüe der Landwirthschaft, 1853, p. 30