Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Luise Duchess of Mecklenburg [-Strelitz], known as Queen Luise of Prussia , full name: Luise Auguste Wilhelmine Amalie Duchess of Mecklenburg (born March 10, 1776 in Hanover , † July 19, 1810 at Hohenzieritz Castle ) was the wife of King Friedrich Wilhelm III. of Prussia .

Contemporaries described her as beautiful and graceful, her informal manners seemed to them more bourgeois than aristocratic . Her life was closely linked to the dramatic events in the struggle between Prussia and Napoleon Bonaparte . Since she died early, she remained young and beautiful in the imagination of subsequent generations. Already during her lifetime she became an object of almost cultic veneration. After her death, this tendency continued. As the mother of Kaiser Wilhelm I, she became a symbol of the rise of Prussia and the development towards the German Empire . Her historical significance lies in the legendary fame that she actually had as Queen of Prussia.

The life

Parental home and childhood

Luise's family background was the result of functional connections among the high nobility across the borders of the small German states. Her father, Duke Karl zu Mecklenburg [-Strelitz], was a later-born prince from the house of the dukes of Mecklenburg-Strelitz . After studying in Geneva and some trips, he took on the representative and well-paid job of taking over the Electorate of Hanover as governor for his brother-in-law, the British King George III. manage. Although he was born in Great Britain , he came from the House of Hanover and had his German home country rule from London .

In 1768 Karl married the 16-year-old Princess Friederike von Hessen-Darmstadt in Hanover . Five of her ten children died early, and she only survived the last confinement by two days. When she died at the age of 29, her daughter Luise, Princess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, was only six years old. The widower married the younger sister of the deceased - Luise got her aunt to be her stepmother - but she also died in childbed after only 15 months after giving birth to her son Karl.

A little later the six children were separated. The two sons, Georg and Karl, stayed with their father in Hanover. Charlotte , the eldest of the four daughters, had been married to the regent of the small duchy of Saxony-Hildburghausen since 1785 . The sisters Therese , Luise and Friederike were entrusted to their grandmother in Darmstadt in 1786 for further education. This grandmother, once married to the brother of the ruling Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt and popularly called " Princess George " after the first name of her deceased husband , was a resolute, clever old lady who gave her three granddaughters some freedom in the old palace of the small royal seat of Darmstadt let.

Luise, nicknamed "Jungfer Husch" and "our great Luise" as a child, was still childlike and playful as a teenager. The city pastor of Darmstadt gave the three sisters confirmation lessons . Mademoiselle Salomé de Gélieu , who had previously run a boarding school for girls in Neuchâtel, Prussia , and worked in England as an educator in aristocratic families, provided the essential training in French and courtly etiquette . In addition, the princesses received lessons in English, history and German as well as drawing and painting and playing the piano.

Luise was not an eager student. Her letters, written in French, remained flawed for life and only much later, in Berlin, did she begin to close some of the greatest educational gaps. There she was informed about history and philosophy and asked friends like Marie von Kleist and Karoline von Berg to help them choose what to read. Frau von Berg (1760–1826), her lady-in-waiting, mentor and confidante, ran a literary salon in her villa at Berlin's Tiergarten and corresponded with celebrities such as Goethe , Herder , Jean Paul and the Baron von und zum Stein . Luise received tips on contemporary literature from her, and requested texts from her “which you assume will please me and will be of the greatest use to me”. In a letter to Marie von Kleist, the cousin of the poet Heinrich von Kleist , her literary inclinations become clear: "May God keep me from cultivating my spirit and neglecting my heart"; she would rather “ throw all the books into the Havel ” than place the mind above feeling.

The life of the princesses in Darmstadt was interrupted by frequent visits to the numerous relatives from Hessian and Mecklenburg noble houses, by trips to Strasbourg and the Netherlands . One often stayed in Frankfurt am Main , where the older sister Therese had been married since 1787 to the then not quite befitting but very wealthy later Prince Karl Alexander von Thurn und Taxis . Several times the 14-year-old Luise and her younger sister Friederike made visits to the house of Frau Rat Catharina Elisabeth Goethe , the mother of the famous poet; Years later, she wrote to her son about it in Weimar : "The meeting with the Princess of Mecklenburg made me extremely happy ... from a stiff court etiquette, they were there in full freedom - dancing - sang and jumped the whole day ..." They were also in Frankfurt in 1792 on the occasion of the coronation celebrations for Franz II. , the last Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire , who in 1804 as Franz I became the first Emperor of Austria . Luise opened the ball in the Austrian embassy together with the young imperial count Klemens von Metternich , who later became famous diplomat and statesman.

At the beginning of March 1793, the two sisters, now 17 and 15 years old, were introduced to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm II in Frankfurt , who reported on this encounter in a letter: “When I saw the two angels for the first time, it was at the entrance to the comedy I was so amazed by her beauty that I was completely beside myself when my grandmother presented her to me. I very much wish that my sons would like to see them and fall in love with them [...] I did my best to ensure that they saw each other more often and got to know each other properly. […] They said yes and the promise will soon be made, presumably in Mannheim. The eldest marries the eldest and the youngest the youngest. ”For the first time Luise met the“ eldest ”, the 22-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, on March 14th, 1793, on March 19th he made his personal marriage proposal and found on April 24th the official engagement took place in Darmstadt. In the marriage contract it was stated that Luise should receive a certain sum "at her own disposal", which would increase significantly with the birth of a son; nothing of the kind was intended for a daughter. Meanwhile, Prince Louis , the “youngest”, was engaged to Luise's sister Friederike, reluctantly, however, and only for reasons of state - he was already in love elsewhere, but in love with his class. The double wedding was agreed for Christmas 1793.

The Crown Princess

On December 22nd, the sisters arrived in the festively decorated city of Berlin. A little girl dressed in white greeted the princesses with a poem, Luise lifted the child up, kissed it - and reacted noticeably blankly when she was told that such behavior was not appropriate for her high position. This incident, often passed on, gave the first impetus to Luise's extraordinary popularity among the Berlin population. On December 24, 1793, she was married to the Crown Prince after an old court ceremony in the White Hall of the Berlin Palace . According to eyewitness reports, the groom, otherwise rather shy and introverted, looked cheerful and exuberant that day. Two days later, Friederike and Prince Louis married.

The couple moved into two neighboring buildings on Unter den Linden , the Kronprinzenpalais and the later so-called Prinzessinnenpalais . This is where the famous “ Princesses Group ” by the sculptor Gottfried Schadow was created in 1795 , commissioned by King Friedrich Wilhelm II. The artist temporarily had a work room in the Kronprinzenpalais, saw the sisters frequently and was even allowed to take their measurements “according to nature”. Luise's husband, the Crown Prince, was, however, dissatisfied with the natural, body-hugging depiction despite the plentiful drapery. In addition, Friederike, now widowed, got pregnant in the year of mourning and, married "in a hurry," had to leave the court and Berlin. When Luise became queen, the sculpture disappeared from the public for decades.

Life at the Prussian court required Luise to adapt to unknown people, rules and duties. Her casual nature stood in the way many times. An experienced lady-in-waiting, Countess Sophie Marie von Voss , was placed at her side as chief steward . She was 64 years old when Luise arrived in Berlin and had been in the service of the royal family for decades. After initial conflicts between her strict professional view and Luise's tendency to unconventional behavior, she was an indispensable teacher of court etiquette to the Crown Princess and later Queen and remained a trusted advisor and friend to her until the end. Another confidante was her first lady-in-waiting, the unmarried Henriette von Viereck (1766-1854), who, as a young woman, had once counted among the favorites of Friedrich Wilhelm II and was to be made countess in 1834.

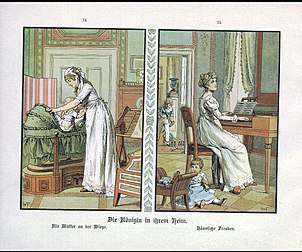

It was helpful for Luise to get used to the new situation that Friedrich Wilhelm refused any kind of conventional formality in the private sphere. The couple used simple manners, which were unusual in these circles. People used the terms of each other and spoke of each other as "my husband" and "my wife". Walks without a retinue on the street Unter den Linden , visits to popular amusements such as the Berlin Christmas market and the “ Stralauer Fischzug” obviously corresponded to their personal inclinations and were noted with approval by the population. Their penchant for simplicity also determined the choice of homes. In Berlin they preferred the Kronprinzenpalais to the palace, they preferred to spend the summer months near the royal seat of Potsdam in the Paretz Palace , an early classicist country palace that is famous for its paper wallpapers. The simple castle, which contemporaries also dubbed “Still-im-Land Castle” because of its location, offered Friedrich Wilhelm relaxation from his official duties and Luise the country air and tranquility that she particularly valued during her numerous pregnancies.

As a mother, Luise fulfilled all the expectations that were placed on her. In almost 17 years of marriage, she gave birth to ten children, seven of them reached adulthood - an above-average rate for the medical and hygienic conditions at the time - and some reached top positions. Her eldest son Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Was King of Prussia from 1840 to 1861, the next-born Wilhelm (I) succeeded his brother on the throne and became German Emperor in 1871 . The daughter Friederike Charlotte married the heir to the throne Nicholas (I) of Russia in 1817 and thus became Russian Tsarina in 1825 under the name Alexandra Fjodorovna. The children had always grown up close to their parents. Although their education was largely left to employed educators and the relationship of the king to the children is sometimes described as quite distant, the image of a large, happy family was presented, a model for the emerging bourgeois society of the 19th century.

The young queen

Friedrich Wilhelm II died on November 16, 1797. His death was not only mourned in Prussia. With his unhappy foreign policy, mistress economy and extravagance, he had badly damaged the country and its reputation. His son, Friedrich Wilhelm III., Was only 27 years old when he took office, shy in public and poorly linguistically expressive, undecided before decisions and hardly prepared to rule a troubled kingdom in difficult times; at his side, Luise became queen at the age of 21.

The last important foreign policy act by Friedrich Wilhelm II was the separate Treaty of Basel in 1795. Prussia left the alliance that had formed in the First Coalition War against France, the left bank of the Rhine was lost, and northern Germany was declared neutral. The peace bought in this way gave Prussia a number of "quiet years", as they were called in retrospect. The domestic policy of the new king was determined by strict thrift, and he could not make up his mind about the overdue, fundamental reforms in administration and the army. Outwardly, he relied on neutrality at almost any price.

Luise's sister Friederike, with whom the Queen had always had a particularly close relationship, caused concern. Princess Louis, as she was called after their marriage, was widowed after a short, loveless marriage in 1796 at the age of 18. She had numerous affairs in her widow's residence, Schloss Schönhausen . “She knows how to comfort herself all too well,” wrote Countess Voss in her diary. Finally there was a scandal: Friederike was expecting an illegitimate child. Luise only found out about it late, shortly before Christmas 1798, and was particularly deeply disappointed by the lack of trust in her. Friederike had to hurry to marry Prince Solms-Braunfels , the alleged child father, she lost her title and court, the couple had to leave Berlin, the two children from their first marriage stayed in the capital. In a third marriage with the Duke of Cumberland , Friederike finally became Queen of Hanover in 1837.

Friedrich Wilhelm and Luise went on several so-called homage trips. In May and June 1798 they drove through Pomerania , East Prussia and Silesia , from May to July 1799 to the western parts of the country, to Franconia and Thuringia . In August 1800 they climbed the Śnieżka Mountain in Silesia, an excursion that the Queen later described as a particularly happy moment in her life. On all these trips, the population was enthusiastic about the appearance and demeanor of the queen. It aroused similar enthusiasm in the capital, even among members of the diplomatic corps . A secretary of the British legation wrote to his sisters: “In Berlin society, especially among the younger generation, there is a feeling of knightly devotion to the queen [...] Few women are gifted with so much loveliness as she [...] But I have to pause , or you will think that my head is twisted, like so many heads are, by the beauty and grace of Queen Luise of Prussia. "

In the meantime Napoleon's pressure on Northern Germany had increased again. An alliance between Prussia and Russia seemed a suitable antidote. In May and June 1802, Friedrich Wilhelm III. and Queen Luise in Memel and met there with Tsar Alexander I of Russia. The politically quite insignificant encounter nevertheless left lasting traces in Luise's descriptions of life. The queen was most impressed by the young tsar. In their notes one reads: “The emperor is one of the rare people who combine all amiable qualities with all real advantages [...] He is wonderfully well built and of a very stately appearance. He looks like a young Hercules . ”For his part, the Tsar was fascinated by Luise. Friedrich Wilhelm III. reacted not jealously but proudly, as always when his wife was admired. Several biographers suggest whether an intimate relationship could have existed between Luise and Alexander. The answer is always: with a probability bordering on certainty not.

In the years 1803 to 1805 various trips took the royal couple to the Franconian possessions, to Darmstadt, to Thuringia and Silesia. From October 25 to November 4, 1805, Tsar Alexander was in Potsdam to win the king over to a new war alliance that Austria and Russia had concluded against Napoleon. Friedrich Wilhelm III. hesitated, but ordered mobilization as a precaution . In December 1805 the Russians and Austrians were defeated in the Battle of the Three Emperors near Austerlitz. In June and July 1806 Friedrich Wilhelm and Luise went to Bad Pyrmont for a cure - this is where the “quiet years” in Prussia ended.

War and flight

On July 12, 1806, the treaty on the Confederation of the Rhine was concluded in Paris , and Napoleon considerably expanded his sphere of influence in German territory. Prussia felt provoked, but the king was still undecided; It was only at the urging of various advisors such as Minister Freiherr vom Stein, Lieutenant General Ernst von Rüchel and Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, and under the influence of his wife, who saw Napoleon as a “moral monster”, that he changed his mind and declared France on October 9, 1806 the war. As the center of this so-called "war party", Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz probably reached the height of her political influence. Only five days later the poorly led, separately fighting Prussian troops suffered devastating defeats near Jena and Auerstedt , the reserve army was defeated near Halle and almost all fortified cities surrendered without a fight. On October 27, 1806, Napoleon entered Berlin as victor.

Friedrich Wilhelm III. and Luise had stayed near the theater of war, in the chaos of the collapse they had to save themselves on separate ways. Luise came with the children, her personal physician Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland and the Countess Voss via several intermediate stops - Auerstedt , Weimar and Blankenhain - to Königsberg . There she fell seriously ill with "nerve fever", as typhoid was called at the time .

While she was still sick, Napoleon threatened to reach Königsberg with his army. Hufeland offered to stay behind with the queen, but she refused: "I would rather fall into the hands of God than this person." The only place of refuge was Memel in the far north-east of the country. In heavy frost and blowing snow, the group around the seriously ill Luise had to cover the headland of the Curonian Spit , which was hardly passable in winter. After three strenuous days and extremely uncomfortable nights, the goal was reached, and Hufeland was surprised to see a certain improvement in the queen's condition. This episode too, told or illustrated more or less dramatically, is a permanent fixture in all the biographies and legends about Luise, as does her encounter with Napoleon.

Luise and Napoleon in Tilsit

Friedrich Wilhelm III. came to Memel by other means, where the royal couple also met the Russian tsar, who promised his unconditional support. But 14th June 1807 defeated Napoleon in the Battle of Friedland , the army of Alexander together with the last remnants of the Prussian troops. The subsequent peace negotiations took place in a splendid tent on a raft in the Memel River (Nyemen). The Prussian king was initially only admitted as a marginal figure when Russia concluded its separate peace with Napoleon. Because it could be foreseen how ruthless the French Emperor would be with the previously defeated Prussia, the Prussian negotiator, Count Kalckreuth , submitted his opinion to the king “that it would be of good effect if Her Majesty the Queen could be here, and sooner , the better ”. But now Friedrich Wilhelm had written to his wife shortly before in Memel about how he had experienced Napoleon: “I saw him, I spoke to this monster spewed out by hell, which Beelzebub formed to become the plague of the earth ! […] No, I have never experienced a tougher test… ”Nevertheless, he passed on Kalckreuth's suggestion. Luise replied: “Your letter with the supplement from K. reached me late last night. Its contents had the effect you anticipated. Nevertheless, my decision was made at the same moment. I'll hurry, I'll fly to Tilsit if you wish. "

The meeting with Napoleon took place on July 6, 1807 in Tilsit, in the house of the Judicial Commissioner Ernst Ludwig Siehr, Deutsche Strasse 24, which Napoleon lived in during the peace negotiations. Luise wore a silver-interwoven white crepe dress and, despite the most fearful tension, looked more beautiful than ever to eyewitnesses. The chief minister, Karl August von Hardenberg , had prepared them in detail for the conversation. He had advised her to be kind, especially to speak as a wife and mother, and not to have an emphatically political conversation. The queen had a surprise. Instead of the dreaded monster, she was faced with Napoleon, an impressive, obviously highly intelligent, pleasantly chatting man. Luise asked for a measured approach to the peace conditions, Napoleon was vague in his answers, but complimented the queen on her wardrobe. When he asked how the Prussians could be so careless as to attack him, Luise gave the often quoted answer: "The fame of Frederick the Great has deceived us about our means."

She later commented positively on her personal impressions during the interview. And since the emperor was also impressed, the time of mutual insults ended here - apart from a later remark by Napoleon that he believed he was hearing “Hardenberg's parrot”. Before that, Napoleon had repeatedly and publicly made very derogatory comments about Luise - she was to blame for the outbreak of war, was “a woman with pretty features, but little spirit ... She has to be terribly tormented by remorse because of the suffering that brought her to her country has. ”After the occupation of Berlin he had parts of the private correspondence found there published; Luise, for her part, had never made a secret of her deep dislike of Napoleon, of her conviction of his amorality.

The queen did not obtain any concrete concessions. The Emperor reported to his wife Josephine in Paris about the one-hour conversation in private : “The Queen of Prussia is really charming, she is full of coquetry with me. But don't be jealous, I'm a wax screen on which everything can only slide. It would cost me dearly to play the gallant. ”In fact, the terms of the Peace of Tilsit of July 9, 1807 were extremely harsh for Prussia. The state lost half of its territory and its population - all areas west of the Elbe and the Polish possessions. A French occupation army had to be supplied. The payment obligations of 400 million thalers far exceeded the country's capabilities. After all, Prussia was preserved as a state - thanks to the intercession of the Tsar, who was very interested in a buffer state between his empire and Napoleon.

In East Prussia

After the humiliating conclusion of peace, Luise saw her main task in raising the king, who was often desperate and spoke of abdication, and giving him support through a happy family life. She herself wavered between depression and hope. In April 1808 she wrote in a letter to her father: “I hope nothing more for my life… Divine Providence unmistakably introduces new world conditions and a different order of things should become, since the old one has outlived itself… and collapses. We fell asleep on the laurels of Frederick the Great ... It can only become good in the world through the good ... therefore I hope that the present bad time will be followed by a better one ... "The" bad time "in Königsberg continued . Luise lacked the sociability of Berlin and could not stand the harsh, East Prussian climate. She suffered from feverish colds, headaches and shortness of breath. In a letter to her brother, she complained: “The climate in Prussia is ... more hideous than it can be expressed. ... My health is completely destroyed. "

Because the Prussian king and his family regarded a return to French-occupied Berlin as an impossible imposition, he ruled the state from Königsberg . Freiherr vom Stein initiated the first, urgent reforms : in 1807 the peasants' liberation, 1808 the urban reform . Scharnhorst , Gneisenau and Boyen led the Prussian army reform . Luise was hardly concerned with the details of these innovations. She had little in common with the mostly rugged and choleric Stein and noted: “He thinks I'm a female who is very superficial anyway.” Stein, who cut his own salary and that of his officials by half, also asked the royal household hefty savings. Except for the queen's jewelry, everything that could be dispensed with was sold. In the winter of 1808/1809, the royal couple went on an eight-week trip to Saint Petersburg at the invitation of the Tsar . Stein had spoken out against the pleasure trip in vain and pointed out that every amount of money available was urgently needed in war-torn East Prussia. Luise enjoyed the balls, dinners and other social events in the Russian residence. But she could not overlook the contrast to her own situation: “It was raining diamonds ... The splendor of every kind is beyond all concepts. The silverware, bronzes, mirrors, crystals, paintings and marble statues available here are enormous. ”Luise's encounters with Tsar Alexander I were rather cool compared to the relaxed atmosphere on earlier occasions.

return

After the French withdrew from Berlin in December 1808, the king initially avoided returning to Berlin in order to emphasize the temporary nature of Prussia's situation. Only after the failure of the Austrian uprising in 1809 did the royal family return to the capital on December 23, 1809. The reception by the Berliners was overwhelmingly warm, both on arrival at the palace and during an evening stroll through the festively illuminated city. A variety of receptions and banquets, from theater and opera performances followed. For the first time, non-noble officers and middle-class families were invited to such festivals.

Regarding the unchanged gloomy political situation, Luise wrote in a letter to Hardenberg on January 27, 1810: “We are still extremely unhappy. Meanwhile, life here in Berlin is more bearable than in Konigsberg. At least it is brilliant misery with beautiful surroundings that distract you, while in Königsberg it was really a real misery. ”Luise actively participated in the efforts to put Hardenberg back into the Prussian civil service, which he had at Napoleon's instigation after the peace von Tilsit had to leave. In him she saw the adviser her husband, who was often indecisive, needed. Despite continuing reservations, Napoleon finally agreed - only Hardenberg trusted him to raise the enormous war contributions with which he had burdened Prussia.

Last journey and death

A planned summer trip to Bad Pyrmont, where Luise hoped to restore her health, had to be canceled, for financial as well as political reasons: Prussia was practically bankrupt and at that time two brothers of Napoleon were staying in Pyrmont. Instead of this trip, a trip to Neustrelitz was decided, where Luise's father had ruled as duke since 1794. “Princess George”, the grandmother from Darmstadt, also lived there in the meantime. Countess Voss, already over eighty years old, took part in the excursion. In a letter to her father it becomes clear how much Luise was looking forward to this family visit: "I glow with joy and sweat like a roast." On June 25, 1810 she arrived in Neustrelitz, the king wanted to come later. After a short stay in the royal seat, they moved to Hohenzieritz Castle , the ducal summer residence. After two previous short visits by her father in Hohenzieritz (1796 and 1803), Luise was for the third time in the land of her ancestors, whose name she had in the title of prince.

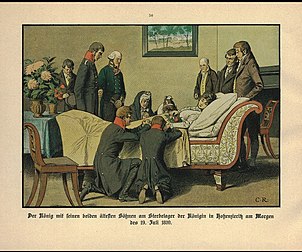

A trip to Rheinsberg was planned for June 30, 1810 ; the trip had to be canceled, however, Luise stayed in bed feverishly. The local doctor diagnosed pneumonia, but it was not life-threatening. The king's personal physician, Ernst Ludwig Heim , who was summoned from Berlin , found no cause for serious concern either. On July 16, he was consulted again because the symptoms - suffocating attacks and circulatory disorders - had worsened. Countess Voss had the king in Berlin notified by express courier, shortly before five o'clock on the morning of July 19, 1810, he arrived in Hohenzieritz with his two eldest sons. Luise died four hours later. She was 34 years old.

The autopsy showed that a lung was destroyed, and a tumor was found in the heart. Countess Voss wrote in her diary: "The doctors say that the polyp in the heart is a consequence of great and lasting grief." With great sympathy among the population, the body was transferred to Berlin, laid out for three days in the Berlin City Palace and on July 30th buried in the Berlin Cathedral .

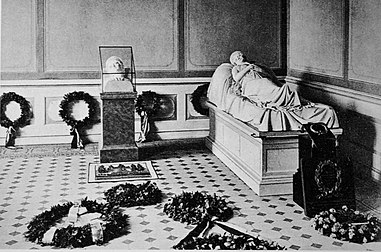

Five months later, on December 23, 1810, Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz found her final resting place in a mausoleum that had meanwhile been rebuilt by Heinrich Gentz with the help of Karl Friedrich Schinkel in the park of Charlottenburg Palace. The grave sculpture of the queen, a masterpiece of the Berlin sculpture school , was created by Christian Daniel Rauch between 1811 and 1814; Friedrich Wilhelm III. had accompanied the development process intensively with many requests and suggestions. He himself was buried in the same place in 1840. The mausoleum developed into a national pilgrimage site , the most important place of worship for Luisen worship.

progeny

- Stillborn daughter († October 7, 1794)

- Friedrich Wilhelm (October 15, 1795 - January 2, 1861), King from 1840, ⚭ 1823 Princess Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria

- Wilhelm (March 22, 1797 - March 9, 1888), King from 1861, German Emperor from 1871, ⚭ 1829 Princess Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

- Charlotte (July 13, 1798 - November 1, 1860), as Alexandra Feodorovna ⚭ 1817 Tsar Nicholas I of Russia

- Friederike (October 14, 1799 - March 30, 1800)

- Carl (born June 29, 1801; † January 21, 1883) ⚭ 1827 Princess Marie of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

- Alexandrine (* February 23, 1803; † April 21, 1892) ⚭ 1822 Grand Duke Paul Friedrich of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Ferdinand (December 13, 1804 - April 1, 1806)

- Luise (February 1, 1808 - December 6, 1870) ⚭ 1825 Prince Friedrich of the Netherlands

- Albrecht (October 4, 1809 - October 14, 1872)

- ⚭ 1830 Princess Marianne of Orange-Nassau

- ⚭ 1853 Rosalie von Rauch , later Countess von Hohenau , daughter of the Prussian Minister of War and General of the Infantry Gustav von Rauch and his second wife Rosalie, née von Holtzendorff

Her descendants include King Harald V , Queen Margrethe II , King Carl XVI. Gustav , King Felipe VI. and Prince Philip .

reception

First forms of public commemoration

As early as July 29, 1810, ten days after Luise's death, the citizens of Gransee applied for a memorial to Luise to be erected on the spot where the funeral procession had stopped at night on the way to Berlin. The king agreed, but on the condition that only voluntary contributions and no public money should be used. Karl Friedrich Schinkel provided the design, the Royal Prussian Iron Foundry in Berlin produced the monument, and the inauguration took place on October 19, 1811.

Soon afterwards, Friedrich Wilhelm III. the impetus to commemorate the deceased in official form. Up until then, gestures of veneration had developed rather spontaneously, out of the affection of the population. In 1813 the king donated the Iron Cross and retrospectively determined March 10th, Luise's birthday, as the foundation date. He made a draft himself and Schinkel carried it out. In 1814, the Luisen Order was founded, an award that was given exclusively to women for special merits.

The myth

The common queen

The story of Luise's mythical transfiguration is also a story of changing motifs. At the beginning, in addition to her beauty and grace, it was above all the signs of simplicity and cordiality that were understood as civil virtues and earned her applause and admiration. The particular intensity of this veneration can be understood against the background of the French Revolution and its course. The open-minded middle class in Germany certainly had sympathy for the initial ideas of the revolutionaries. When their demands finally led to violence and terror, the mood in Germany changed. They wanted reforms, but without violence. One wanted the recognition of bourgeois values, but “from above”, within the framework of a constitutional monarchy . Luise and her family seemed to be ideal models for these hopes.

Important poets and writers of the time - Novalis , Kleist, Jean Paul , August Wilhelm Schlegel and others - paid homage to the young queen. Above all, Novalis, actually Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg, caused a sensation with his programmatic essay Faith and Love or The King and the Queen , which was published in the summer of 1798 in the newly founded monthly magazine Jahrbücher der Prussischen Monarchy under the government of Friedrich Wilhelm III. appeared. He had preceded his text with a series of exuberant poems to the royal couple. In the subsequent prose fragments he sketched a picture of a society in which the family and the state, the bourgeoisie and the monarchy were linked by faith and love. The king would reform the country, promote the arts and sciences. The queen would be the object of identification for all women in terms of beauty, morality and domestic activity, and her portrait should hang in all living rooms. Friedrich Wilhelm III. refused the text. He could not recognize himself, his abilities and intentions in it, he did not like flattery, and a monarchy on a parliamentary basis did not correspond to his ideas. He did not allow the planned continuation of the article in the yearbooks . Nevertheless, he and Luise remained hopeful for the wishes of the citizens of Prussia.

When comparing the numerous pictures that were painted by Luise up to her death in 1810, it becomes clear that hardly any portrait is the same as another. This peculiarity was also noticed by contemporaries. An explanation was found in the Berliner Abendblatt of October 6, 1810: “During Her Majesty's lifetime, no Mahler succeeded in producing a somewhat similar picture of her. Who would have dared to want to reproduce this sublime and yet so cheerful beauty? ”After her death, after“ the depressing comparison with the inaccessible original can no longer take place ”, more precise images became possible. Such later representations were often based on copies of Luise's death mask, which the ducal architect and court sculptor Christian Philipp Wolff had removed in Hohenzieritz.

The martyr

With the defeat of Prussia by Napoleon, a new motif came to the fore in the Luisen cult: the test in difficult times, the transformation of the graceful, cheerful and citizen-oriented beauty into an adorable sufferer. The terms “sacrifice” and “suffering” were central categories used by historians and artists of the time to interpret Luise's role: According to this interpretation, she accepted the humiliations that came from France for her entire country. In Tilsit she bravely faced the most powerful man in Europe - more resolutely than her hesitant husband - and sacrificed herself for her people in the fruitless pleading to an enemy whom she regarded as a moral monster. She experienced firsthand the hardships of the war and eventually died, according to the widespread interpretation of the medical findings, of a broken heart.

In this role she became a leading figure in the wars of liberation soon after her death , and the wars were stylized as a campaign of revenge for a patriotic martyr . The poets of the Wars of Liberation expressed themselves entirely in this sense. Theodor Körner wanted to pin the portrait of Luise as a “holy image for the just war” on the flags of the freedom warriors and rhymed: “Luise is the protective spirit of the German cause. Luise is the watchword for vengeance. ” Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué , like Körner, a volunteer warrior and poet, described the“ lovely legend that Queen Luise was alive, that her death was only a deception… Who could have contradicted that? "And according to a popular anecdote, the Prussian Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher , when he reached Paris on July 7, 1815 after the battle of Waterloo , after the final victory over Napoleon, shouted down from Montmartre :" Now, at last, Luise has been avenged ! "

The Prussian Madonna

The school system was geared towards conveying the officially desired image of Luise and thus constantly reproducing it for new generations. The actual learning material was restricted to the bare essentials, especially in elementary schools, with religion and the patriotic in the foreground. Luise was mentioned almost everywhere, as learning, reading and edifying material in the subjects of history, German and religion, but also in mathematics and geography. Patriotic days of remembrance deepened the bond with the model Luise. By order of the school authorities, classes at all girls' schools were canceled on her 100th birthday, instead the pupils heard a lecture on “the image of the illustrious woman ... who, in times of deepest suffering, worked so sacrificially in the uprising of the people and all those who came Set a high example by gender ”.

Luisen-Linden trees were planted in a number of communities on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of death.

Lexicons and encyclopedias supported the myth. They appeared with the claim to disseminate objective knowledge, but also served to create legends . Already in a "Conversationslexicon" from 1834 it was said: "Early on she was used to linking everything visible, earthly to an invisible, higher and the finite to the infinite"; and in a "Ladies Conversations Lexicon" Luise was described as an "angel of peace and mildness" and "mother of all her subjects".

Gradually, the maternal aspect of the veneration of Luise became more and more important, according to the share of her sons in the rise of Prussia and in the founding of the empire. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV., Her eldest son, had declared in 1848: "The unity of Germany is close to my heart, it is an inheritance of my mother." In the triumph of the second eldest son, Wilhelm I, the symbolic effect of Luise reached its climax. Napoleon III , the nephew of her great adversary Napoleon Bonaparte, declared war on Prussia on July 19, 1870, exactly on the 60th anniversary of her death. Before going to war, Wilhelm I knelt by his mother's sarcophagus. Unlike in 1806, the campaign for Prussia ended victorious. Wilhelm was proclaimed emperor in Versailles the following year ; on his return on March 17, 1871, he again looked for his mother's grave in Berlin. According to these symbolic historical events, Luise's life and work belonged to the indispensable and systematically widespread founding myths of the empire, in the public presentation a direct line led from her so-called sacrificial death to victory over Napoleon and to the establishment of an empire.

After her son Wilhelm became emperor, pictures of Queen Luise in her role as mother increased. Painters such as Gustav Richter and Carl Steffeck , sculptors such as Erdmann Encke and Emil Hundrieser contributed to the veneration of Luisen. The statue "Queen Luise with Prince Wilhelm" by Fritz Schaper , the so-called Prussian Madonna - Luise steps majestically down a staircase and holds the future emperor like the baby Jesus in her arms, met with a particular response . The statue was created in 1897 as a larger than life stucco figure for a festival street, then transferred in marble on the instructions of Emperor Wilhelm II . Numerous reductions in ivory , plaster of paris or marble were made from this work for private use. The original is lost today.

The book market was abundantly supplied with trivial literature about Luise, mostly intended for young women, often illustrated with sweetish illustrations. 391 relevant poems were counted, including Queen Luise as a typical example . A picture of life. Dedicated to German youth by Marie von Felseneck. The work of this author of more than 50 girls' books concluded with the words “Yes, an angel in gentleness and mildness, in beauty and majesty was the eternal one [...] and as long as German tongues continue to tell of German princely virtues, the name will be queen Luise shine in bright, high glory ”.

The large-format illustrated book Die Königin Luise was somewhat more demanding in terms of quality and highly successful . In 50 pictures for young and old by the uniform and battle painters Carl Röchling and Richard Knötel , first published in 1896.

- Illustrations from: The Queen Luise. In 50 pictures for young and old

Various nineteenth-century biographers and historians endeavored to take a more differentiated approach without seriously questioning the state-imposed myth, which was believed to be valuable for popular education. The writer Friedrich Wilhelm Adami wrote a biography based on notes from Caroline von Berg, which appeared for the first time in 1851 and which was reprinted 18 times. The author clearly showed his admiration for Luise, but also distanced himself from some legendary decorations. In 1876 the historian Heinrich von Treitschke gave a much-cited official speech on Luise's 100th birthday. In the introduction he expressed some reservations about what he called “popular tradition” and declared that science should not follow an ideal, but must also show the limits of noble people. But then he scarcely distanced himself from the widespread biographies, used expressions such as “consuming grief over the fate of the country (to which her delicate body) succumbed” and emphasized the queen's female passivity as a special advantage: “… but never with one Steps she exceeded the barriers which the old German custom placed on her sex. It is the touchstone of her women's sovereignty that so little can be said of actions. "

In general, Luise's transfigured image lacked all traits of direct political effectiveness, although there are numerous testimonies to her participation in the endeavors of the Prussian reformers - especially for Hardenberg she had made a decisive contribution - and for the fact that she allowed the often undecided king to make important decisions tried to initiate war against Napoleon. Friedrich Wilhelm III. In his memoirs himself he had clearly stated on this question: "Many people have been delusional as if my wife had a certain influence on the affairs of government", but in fact this was absolutely not the case. Luise's deeply felt attachment to the difficult fate of the people was emphasized again and again, but also the “feminine” passivity of her sympathy. "Early on she saw the barriers that both nature and human constitutions have placed on her gender." Her effectiveness, it was said, consisted primarily in the fact that she gave the king a happy family environment.

Accordingly, elements perceived as feminine were also the focus of various institutions that referred to Luise. The Luisen Order was awarded to women for providing "refreshment and relief to the men of our brave armies ... with caring care". In addition to several girls' schools, a monastery was named Luises, which had cared for “neglected and abandoned boys” since 1807, as well as a foundation from 1811 in which German teachers were trained - they were supposed to work in noble families instead of the French governesses . In the appeal for donations for this foundation, particular emphasis was placed on Luise: "Your sense of domesticity, your true love for your husband and your children, your feeling for everything that is good and noble and great."

Weimar Republic and "Third Reich"

To a limited extent, Luise also served as a figure of identification in the first German republic , although the veneration was no longer supported by the state. Her steadfastness in difficult times was transferred to the difficult situation after the lost First World War . It was used as a model in particular by political groups such as the German National People's Party and the Bund Queen Luise . The DNVP was a right-wing conservative monarchist party, which in 1933 converted to the unity party of the “Third Reich” , the National Socialist German Workers' Party; in her election campaigns she had used posters with the image of Queen Luise. The Bund Königin Luise, a monarchist women’s organization, existed between 1923 and 1934 and was politically close to the “Stahlhelm” (Stahlhelm ”) anti- democracy group .

During the National Socialist tyranny from 1933 to 1945, the Luis cult continued to lose importance. People accepted it when Luise was occasionally remembered, but did not use her for their own propaganda , not even to advertise the high number of children sought by the state. The traditional image of the passively suffering woman did not fit into the ideological concept of male strength and toughness as it was propagated at the time.

End of the myth

The Luisen worship in its traditional form ended at the latest after the Second World War . In 1947 the victorious Allies formally dissolved the state of Prussia. In both post-war German states, the term Prussia was increasingly associated with militarism and a subject mentality. In the Federal Republic of Germany , a more differentiated assessment of Prussian history began towards the end of the 1970s, and the GDR followed even later, where relics from this period were handled particularly rigorously. Queen Luise was the center of a myth that for almost 150 years had more or less directly related to the “hereditary enemy” France. In the second half of the 20th century, this reference had become obsolete. The ideal of women that Luise was supposed to embody - the personal union of a devoted wife, a multiple mother and an unshakable sufferer who served the fatherland - had lost its relevance and attraction.

Critical voices

For more than a century, unconditional praise, admiration, and almost adoration determined Luise's public image. In the background, so to speak, there were always dissenting voices - they concerned the person of the queen as well as the sometimes excessive veneration that was shown to her. Luise herself had registered the critical attitude of Freiherr vom Stein towards her. Another critic from personal experience was Friedrich August Ludwig von der Marwitz . The general and ultra-conservative politician, a staunch opponent of the Stein-Hardenberg reforms, had access to the Prussian court through his wife. In Luise he observed the “triumph of beauty and grace”, although she “never got into the case of doing deeds which could have shown her such exuberant love and admiration”; also she had hardly come into contact with the people, except "perhaps through individual words that one heard from her - and these were by no means witty". He also disliked “their vanity. She was aware of her beauty [...] and loved the plaster more than was necessary. "

The writer and diplomat Karl August Varnhagen von Ense reported about Alexander von Humboldt that the violent worship of Luisen caused him to express himself negatively about Luise's character. Theodor Fontane valued the Queen's “purity, splendor and innocent tolerance”, but firmly refused, which was obviously not in accordance with historical truth. In the walking tour through Mark Brandenburg he wrote in 1862: "More than by the defamation of their enemies has Louise of the phrase had to suffer nhaftigkeit her admirers. She did not die of the 'misfortune of her fatherland', which she certainly felt bitterly enough. Exaggerations, which try to ascribe emotions to the individual, only provoke contradiction. ”The Marxist historian and social democrat Franz Mehring took up the episode in which vom Stein advised against the costly trip of the royal couple to Saint Petersburg in 1808 in view of the plight of the population in East Prussia would have. Mehring saw the trip as a typical example of the social irresponsibility of the royal family. He called the veneration of Luise a " Byzantine hoax".

present

Today Luise is no longer a mythically transfigured cult figure. However, she is perceived as an interesting, emotionally touching personality in German history. Historians and writers deal with it - with people and with myth. Institutions, streets and squares bear their names. One value of the stamp series " Women of German History " of the Deutsche Bundespost, issued in 1989, shows her portrait.

Souvenir trade and tourism are using them again, especially in Berlin. A Queen Luise route , initiated by the administration of the State Palaces and Gardens of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg , was completed by the 200th anniversary of Luise's death in 2010: 10 stations in her life between Hohenzieritz in the north and Paretz in the south can be visited on this route. In 2010, the renovation of the mausoleum in the park of Charlottenburg Palace, including the horticultural restoration of the area according to historical standards, was completed. At the place where she died , where there is a memorial , and in Neustrelitz , events on the subject of Queen Luise take place every year.

On June 18, 2009, a monument to Luis that was demolished in GDR times was put up again in Magdeburg . In the commemorative year 2010, various exhibitions on the subject of Luise were held in Berlin and Brandenburg. In the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin : Luise. Life and Myth of the Queen. On the Pfaueninsel in Berlin: The Queen's island world and in Paretz Palace: the Queen's clothes. On the 200th anniversary of her death (July 19, 2010), the Queen Luise Association was founded by women from all over Germany in Crimmitschau in memory of Luise . To distinguish it from the political goals of the old federal government, a different order in the name was deliberately chosen. Outside of Hohenzieritz Castle, the Villa Vier Jahreszeiten in Crimmitschau is home to one of the few permanent exhibitions on Luise (adoration of Luise in the imperial era with an extensive library).

Foundations

Luise had herself and after her death foundations were set up in her name or in her memory . These include the following foundations:

- In 1807 she was the namesake of the Luisenstift, an "educational institution for poor boys". At the endeavor of the Society of Humanitarian Friends, she not only gave her name, but also took on the maintenance of four boys.

- After her death, on the first anniversary of her death on July 19, 1811, the Luisen Foundation was founded, an "institution for the education of young girls". This foundation still exists today as a private school .

- A foundation appealed to her name, which annually on the anniversary of their death paid the poor and so-called Luisenbräuten part or all of the trousseau .

Monuments and honors

There are numerous Luis monuments in honor of the Queen of Prussia .

The following are also named after her:

- Luisenstadt , district of Berlin (1802)

- Luisenbad (Berlin) (around 1809)

- Louis Order (1814)

- Luisenstraße , common street name (early 19th century)

- Luisenplatz , a common name for public spaces

- Louisendorf , part of the community Bedburg-Hau (1820)

- Queen Luise Memorial Church (Kaliningrad) (1901)

- Luisenpark (Erfurt) , 1903

- Queen Luise High School , Erfurt, 1903

- Queen Luise Memorial Church (Berlin) (1912)

- Queen Luise , passenger ship (1913)

- Queen Luise , passenger ship (1934)

- Luisenkirche

- Luisenburg rock labyrinth Natural monument, stone block sea named after Queen Luise

- Luisenhospital Aachen Evangelical Hospital Association in Aachen from 1867

- Prussian Madonna , statue in Berlin, destroyed in 1945

Movies

- 1913: The film by Queen Luise . Director: Franz Porten , Actor: Hansi Arnstädt (Queen Luise)

- 1927: Queen Luise . 1st part: The youth of Queen Luise. Directed by Karl Grune

- 1927/1928: Queen Luise. Part 2. Directed by Karl Grune

- 1931: Luise, Queen of Prussia . Directed by Carl Froelich , actress: Henny Porten

- 1957: Queen Luise Director: Wolfgang Liebeneiner , Actress: Ruth Leuwerik (Queen Luise)

- 2005: Vivat - Queen Luise in the Fichtel Mountains. Director: Gerald Bäumler

- 2010: Luise - Queen of Hearts. Scenic documentation, Germany, 52 min., 2009, book: Daniel Schönpflug, director: Georg Schiemann , production: Looks, NDR , arte , first broadcast: January 9, 2010 on arte , film information from ARD .

- 2013: Queen Luise - The Prussian Madonna. Staged documentary in the series Women Who Made History , Germany, 50 min., Book: Stefan Brauburger , Cristina Trebbi, directors: Christian Twente and Michael Löseke, first broadcast on December 15, 2013 on ZDF, film information

See: Rolf Parr: "That is unnatural, worse: bourgeois" - Queen Luise in the film. In: Discourses of Time. Reflections on the 19th and 20th centuries as a commemorative publication for Wulf Wülfing. Edited by Roland Berbig, Martina Lauster, RP Heidelberg, Synchron, 2004, ISBN 3-935025-55-6 , pp. 135–164 (with illus. And filmography).

literature

swell

- Karl Griewank (ed.): Queen Luise. Letters and Notes. Bibliographical Institute, Leipzig 1924.

- Heinrich Otto Meisner (ed.): From the life and death of Queen Luise. Handwritten notes from her husband, King Friedrich Wilhelm III. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1926.

- Malve Rothkirch (ed.): Queen Luise of Prussia. Letters and Notes 1786–1810. German Kunstverlag, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-422-00759-8 .

- Carsten Peter Thiede, Eckhard G. Franz: Years with Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz. From notes and letters of Salomé von Gélien (1742–1822). In: Archive for Hessian History and Archeology , Volume 43. Darmstadt 1985, ISSN 0066-636X , pp. 79–160.

- Bogdan Krieger : Education and instruction of Queen Luise. In: [1] Hohenzollern yearbook year 1910, p. 112, digitized

Representations

- Silvia Backs: Luise, Queen of Prussia, born Princess of Mecklenburg-Strelilz. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 15, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-428-00196-6 , pp. 500-502 ( digitized version ).

- Paul Bailleu : Luise . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1884, pp. 815-825.

- Paul Bailleu : Queen Luise. A picture of life. Giesecke & Devrient, Berlin 1908, archive.org

- Hanne Bahra: Queen Luise. From the provincial princess to the Prussian myth. Bruckmann-Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7658-1825-7 .

- Franz Blei : Queen Luise of Prussia. In: Ders .: companions. With 20 portraits. Reimar Hobbing, Berlin 1931.

- Christine Countess Brühl: The Prussian Madonna. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 3-351-02713-3

- Günter de Bruyn : Prussia's Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 (with references to quotations, bibliography and list of picture sources).

- Philipp Demandt : Cult of Luis. The immortality of the Queen of Prussia. Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-412-07403-9 .

- Karin Feuerstein-Praßer: The Prussian queens. Pustet, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7917-1681-6 . As paperback: Piper Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-492-23814-9 ( Piper 3814 series ).

- Jan von Flocken : Luise. A queen in Prussia. Biography. Verlag Neues Leben, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-355-00987-3 .

- Birte Förster: The Queen Luise Myth. Media history of the “ideal image of German femininity”, 1860–1960. Edited by Jürgen Reulecke . V & R unipress, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-89971-810-2 (= forms of memories , volume 46, also dissertation at the University of Giessen 2008).

- Paul Gärtner, Paul Samuleit (Ed.): Luise. Queen of Prussia. Help book publisher, Berlin-Schöneberg 1910.

- Claudia von Gélieu , Christian von Gélieu: The educator of Queen Luise. Salomé de Gélieu . Pustet, Regensburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-7917-2043-2 .

- Dagmar von Gersdorff : Queen Luise and Friedrich Wilhelm III. A love in Prussia. Rowohlt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-87134-221-1 . (As paperback: Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-499-22532-8 ( rororo 22615))

- Heinrich Hartmann: Luise, Prussia's great queen. Druffel & Vowinckel, Stegen am Ammersee, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8061-1211-5 .

- Christian Graf von Krockow : Portraits of famous German women. From Queen Luise to the present. List Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-471-79447-6 , pp. 11-57.

- Friedrich Ludwig Müller, Beatrice Härig: Luise. Records of a Prussian Queen. Main volume with booklet. Publication of monuments by the German Foundation for Monument Protection. Bonn 2001, ISBN 3-935208-07-3 .

- Heinz Ohff : A star in weather clouds. Queen Luise of Prussia. A biography. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-492-03198-6 . As paperback: 8th edition. Piper, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-492-21548-3 ( Piper 1548 series ).

- Daniel Schönpflug: Luise of Prussia. Queen of the Hearts. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59813-5 .

- Luise Schorn-Schütte : Queen Luise. Life and legend. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-48023-3 ( CH Beck Wissen 2323).

- Holger Simon : The image policy of the Prussian royal family in the 19th century. On the iconography of the Prussian Queen Luise (1776–1810). In: Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, Volume 60. Cologne 1999, ISSN 0083-7105 , pp. 231-262.

- Thomas Stamm-Kuhlmann : King in Prussia's great times. Friedrich Wilhelm III., The melancholic on the throne. Siedler, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-88680-327-9 .

- Peter Starsy: Queen Luise of Prussia (1776–1810). A search for clues in Mecklenburg. In: Neubrandenburger Mosaik, Vol. 33 (2009), pp. 92-131.

- Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens Berlin-Brandenburg [Ed.]: Luise. The queen's clothes. Exhibition catalog. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7774-2381-4 .

- Johannes Thiele: Luise of Prussia. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-499-50532-4 .

- Sibylle Wirsing : The Queen. Luise after two hundred years. Wjs, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-937989-59-4 .

- Wulf Wülfing: Queen Luise of Prussia. In: Wulf Wülfing, Karin Bruns, Rolf Parr: Historical Mythology of the Germans 1798–1918. Fink, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-7705-2605-8 , pp. 59-111.

- Wulf Wülfing: On the myth of the "German woman". Rahelbettinacharlotte vs. Luise of Prussia. In: Klaudia Knabel, Dietmar Rieger, Stephanie Wodianka (eds.): National myths - collective symbols. Functions, constructions and media of memory. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-525-35581-5 ( forms of memory, vol. 23), pp. 145-174.

Fiction

- Elisabeth Halden : Queen Luise. Meidinger, Berlin 1910 / 7th edition: From the days of Queen Luise [A story for the youth], publisher of popular and youth publications Otto Drewitz Nachfahren, Leipzig 1930. (Elisabeth Halden - pseudonym of Agnes Breitzmann (* May 27, 1841 in Templin ; † November 10, 1916) - was a successful German author of " girls' books " in her time .)

- Bettina Hennig: Luise Königin out of love. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-442-46406-7 . (Roman; Goldmann Taschenbuch 46406)

- Sophie Hoechstetter : Queen Luise. In: Novels of Famous Men and Women. Volume 36. Richard Bong, Berlin 1926.

- Else von Hollander-Lossow : The immortal queen. Easemann, Leipzig 1934. (A "Luise novel")

- Hermann Dreyhaus: Queen Luise. The life picture of a German woman. In: Fatherland folk and youth books of the Union publishing house . Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart / Berlin / Leipzig 1928.

- Egon Richter: Queen Luise's last trip. 3. Edition. Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-373-00234-6 . (First edition 1988)

- Reinhold Schneider : The King's Rose. Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1957.

- Ingrid Feix : That's against all etiquette. Anecdotes about Queen Luise. Eulenspiegel Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-359-02495-8 .

Educational models

- Markus Müller: The myth of Luise of Prussia. A search for clues on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of her death. In: Learn history, H. 137, 2010, pp. 52–56.

Web links

- Literature by and about Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz in the German Digital Library

- Information about Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Literature about Luise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz in the state bibliography MV

- Queen Luise of Prussia on the official website of the House of Hohenzollern

- Patricia Drewes: Queen Luise of Prussia - History in the Mirror of Myth in the Digital Library of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation

- Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Luise von Preussen and her time - Hans Dieter Mueller.

Individual evidence

- ^ Quotations from Günter de Bruyn: Preußens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 43.

- ↑ The Mark Brandenburg. Journal for the Mark and the State of Brandenburg. Issue 65. Marika Großer Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISSN 0939-3676 , p. 4.

- ^ Paul Bailleu: Luise . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1884, p. 816.

- ↑ In addition Eduard Vehse: Preussische Hofgeschichten. Fourth volume. Newly published by Heinrich Conrad , Georg Müller, Munich 1913, pp. 137–139

- ↑ Marlies Schnaibel: Luise, Queen of Prussia. Edition Rieger, Karwe bei Neuruppin 2003, ISBN 3-935231-33-4 , p. 17.

- ^ Paul Bailleu: Luise . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1884, p. 818.

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 36.

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 40.

- ↑ Quotes from Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 43.

- ↑ Siehr: Diary of EL Siehr (1753-1816). Arnstadt 2007.

- ↑ Marlies Schnaibel: Luise, Queen of Prussia. Edition Rieger, Karwe bei Neuruppin 2003, ISBN 3-935231-33-4 , p. 22.

- ↑ The Mark Brandenburg. Journal for the Mark and the State of Brandenburg. Issue 65. Marika Großer Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISSN 0939-3676 , p. 17.

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 45.

- ^ A b c Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 46.

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 48.

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 51.

- ↑ On the question of returning to Berlin see Stamm-Kuhlmann (literature) pp. 304–311

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 52.

- ^ Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , p. 53.

- ↑ Peter Starsy: Queen Luise of Prussia (1776-1810). A search for clues in Mecklenburg. In: Neubrandenburger Mosaik, Vol. 33 (2009), pp. 92-131.

- ^ Günter de Bruyn: Preussens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 48.

- ↑ Illustration from 1838 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Illustration from 1838 ( digitized version )

- ^ Quotations from Günter de Bruyn : Preußens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 74.

- ^ Quotations from Günter de Bruyn: Preußens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 67.

- ↑ Patricia Drewes: Queen Luise of Prussia - history in the mirror of myth. Page 164 of the print edition

- ↑ Patricia Drewes: Queen Luise of Prussia - history in the mirror of myth. Page 163 of the printed output

- ↑ Patricia Drewes: Queen Luise of Prussia - history in the mirror of myth. Page 175 of the print edition

- ↑ Numbers and quotation from Günter de Bruyn: Preussens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 89.

- ^ Quotations from Günter de Bruyn: Preußens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 94.

- ^ Quote from Die Politikerin - Luise interferes

- ↑ Patricia Drewes: Queen Luise of Prussia - history in the mirror of myth. Page 167 of the printed output

- ^ Günter de Bruyn: Preussens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 72.

- ↑ The Mark Brandenburg. Journal for the Mark and the State of Brandenburg. Issue 65. Marika Großer Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISSN 0939-3676 , p. 31.

- ↑ Quotes from Christian Graf von Krockow: Portraits of famous German women from Queen Luise to the present. List Taschenbuch, 2004, ISBN 3-548-60448-X , pp. 20, 26.

- ^ Günter de Bruyn: Preussens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 61.

- ^ Quotations from Günter de Bruyn: Preußens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 58 f.

- ^ Günter de Bruyn: Preussens Luise. About the creation and decay of a legend. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-718-5 , p. 54.

- ↑ Andreas Hentschel: Help for impoverished girls. In Brandenburg leaves. (Supplement to the Märkische Oderzeitung ), April 9, 2010, p. 14.

- ↑ Queen Luise. 1st part: The youth of Queen Luise. ( Memento from October 23, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on filmportal.de. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ↑ Queen Luise. Part 2. ( Memento from March 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on filmportal.de. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

| predecessor | Office | Successor |

|---|---|---|

| Friederike |

Queen of Prussia 1797 to 1810 |

Elisabeth |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Luise Auguste Wilhelmine Amalie of Mecklenburg |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Prussian queen |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 10, 1776 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hanover |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 19, 1810 |

| Place of death | Hohenzieritz Castle near Neustrelitz |