Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments , including the Ten Words ( Hebrew עשרת הדיברות aseret ha-dibberot ) or the Decalogue ( ancient Greek δεκάλογος dekálogos ) are a series of commandments and prohibitions (Hebrew Mitzvot ) of the God of Israel, YHWH , in the Tanakh , the Hebrew Bible . This contains two slightly different versions. They are formulated as a direct speech from God to his people, the Israelites , and summarize his will for behavior towards him and his fellow men. In Judaism and Christianity they are of central importance for theological ethics and have helped shape the church and cultural history of Europe and the non-European West.

The Decalogue in the Tanakh

text

There is a version of the Decalogue in the 2nd book of Moses (Exodus) and in the 5th book of Moses (Deuteronomy), which differ in details:

| Ex 20.2-17 EU | Dtn 5.6-21 EU |

|---|---|

| "I am YHWH, your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the slave house." | |

| "You shouldn't have any other gods besides me." | |

| "You should not make yourself an image of God and no representation of anything in the sky above, on the earth below or in the water below the earth." | "You should not make an image of God for yourself that represents anything in the sky above, on the earth below or in the water below the earth." |

| “You should not prostrate yourself to other gods or commit yourself to serve them. For I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God: with those who are enemies of me, I pursue the guilt of the fathers to the sons, to the third and fourth generations; with those who love me and keep my commandments, I show my graces to thousands. " | |

| “You shall not abuse the name of the Lord your God; for the Lord does not leave him unpunished who misuses his name. " | |

| "Remember the Sabbath: keep it holy!" | "Pay attention to the Sabbath: keep it holy, as the Lord your God has made it your duty." |

| “You can create for six days and do any work. The seventh day is a day of rest, dedicated to the Lord your God. " | |

| You are not allowed to do any work on him: you, your son and daughter, your slave and your slave girl, your cattle and the stranger who has the right to live in your urban areas. | You are not allowed to do any work on him: you, your son and daughter, your slave and your slave girl, your cattle, your donkey and all your cattle and the stranger who has the right to live in your urban areas. Your slave and your slave should rest like you. |

| For in six days the Lord made heaven, earth and sea and all that belongs to them; on the seventh day he rested. | Remember: When you were a slave in Egypt, the Lord your God led you out there with a strong hand and arm held high. |

| That is why the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy. | That is why the Lord your God has made it your duty to keep the Sabbath. |

| Honor your father and mother so that you may live long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you. | Honor your father and mother as the Lord your God has made it your duty so that you will live long and well in the land that the Lord your God gives you. |

| You shouldn't murder. | You shouldn't murder |

| You shouldn't commit adultery. | you shouldn't commit marriage |

| You shall not steal. | you shall not steal, |

| You shouldn't testify wrongly against your neighbor. | you shall not testify wrongly against your neighbor, |

| You shall not ask for your neighbor's house. You shall not long for your neighbor's wife, his slave, his ox or his donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor. | you shall not long for your neighbor's wife and you shall not covet your neighbor's house, his field, his slave or his female slave, his ox or his donkey, nothing that belongs to your neighbor. |

Narrative context

The Sinai story begins in the Torah with Ex 19 EU : After the arrival of the Israelites freed from Egypt on Mount Sinai , YHWH claims them as his chosen covenant people, whereupon they promise Moses to fulfill all of God's commandments. After his theophany, God speaks to Moses on the mountain. Before and after, he instructs him to keep the people from entering the mountain and thus protect them from the fatal sight. At the end, Moses gives the warning to the people ("... and told him."). The sentence can also be translated objectlessly ("and said to him:"): Then Moses would communicate the following Decalo speech to the people, which he would have previously received from God.

Ex 20 EU , however, begins with the unaddressed sentence “Then God spoke all these words”. After the Decalo speech, the people did not react to it, but to the previous theophany: They had fled from the mountain and asked Moses to convey the words of God. He alone approached God; the people only “saw” his speech from heaven. So it heard God's voice but did not understand its content. Thereupon Moses proclaimed the individual provisions of the covenant book (Ex 20.23-23.33). As at the beginning, the people respond with one accord that they want to fulfill all of God's commandments ( Ex 24.4 EU ).

After the covenant meal of the seventy elders, Ex 24.12 EU speaks for the first time of stone tablets that God alone will give to Moses. According to the instructions for building the tabernacle ( Ex 25 EU -31.17 EU ) called Ex 31,18 EU two stone tablets, have described his finger God. According to the context, these contain all of the commandments issued before, not just the Decalogue. According to Ex 32.15–19 EU , God himself made the tablets and described them on both sides. Moses broke these tablets in anger at Israel's apostasy and made new ones on his behalf, of which it says ( Ex 34.28 EU ):

"And he wrote the words of the covenant , the Ten Words , on the tablets ."

The number ten is only found at this point in the book Exodus and in the literary context does not refer to Ex 20, but to the text unit Ex 34.11–26 EU , often called the Cultic Decalogue .

Before the Israelites conquered the land , Moses came back to this in Dtn 4:13 EU : After the Sinai theophany, God revealed the covenant to them and obliged them to keep it in the form of the “Ten Words”. To this end, God wrote them on two stone tablets. For the first time, this highlights the identity of Ex 20: 2–17 with the “Ten Words” and two tables of commandments and emphasizes their status as a covenant document revealed and written down by God himself.

In Dtn 5.1–5 EU , Moses reminds the assembled people that God spoke to the people loudly and directly on Sinai ( called Horeb here ), but that they avoided the mountain out of fear. That is why he, Moses, has been preaching God's words to the people ever since. He then repeats the Decalo speech as a full quotation and then confirms that God himself proclaimed this wording at the time, wrote it unchanged on the commandment boards and gave it to him ( Dtn 5,22 EU ). Only now did the people learn orally the content of the Decalogue, which had already been revealed and written, according to the overall ductus of the Pentateuch. According to Dtn 10.1–5 EU , Moses placed both stone tablets in the ark , which as a movable sanctuary guaranteed God's saving presence among his people until the time of King David ( 1 Sam 5 EU - 1 Sam 6 EU ; 2 Sam 7 EU ).

From this narrative situation, the main questions of interpretation and research arose:

- Who is the Decalogue for?

- How do the two versions relate to each other?

- Which is older and more original?

- How does the Decalogue relate to the rest of the Torah?

Self-introduction to YHWH

The sequence is opened in Ex 20,2 with the theophany formula "I am YHWH", which is common in the Tanach, which is expanded here to include the promise of "your God" and to the tradition of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (Ex 2-15) is related. God does not appear to his people as a stranger, but reminds them with his name of his earlier act of liberation, which already expressed his will.

God's “I” (here in the emphasized Hebrew form Anochi ) appears as a unique legal claim to a collective “you” that excludes all other claims. The address applies to the entire people of God, Israel, chosen in the exodus from Egypt, and to every individual member of this people. God's self-revelation in the history of the Hebrews establishes here his right to all their descendants. That is why the Haggadah impressed on the devout Jew on Passover : "In every generation man looks at himself as if he had left Egypt himself." This exclusivity of God, which makes the people addressed and reminds them of their history of liberation, is a specialty of Judaism among the ancient oriental religions. This differentiates the people of Israel and their relationship to God at the same time from all other peoples, so that the phrase “You shall not have any gods next to me” [literally: before my face] appears as a logical consequence: “Only for him to whom God himself so revealed, the following law also applies. "

The exclusion of foreign gods implied in YHWH's exodus for Israel is unique in the ancient Orient.

Ban on images

The biblical ban on foreign gods is immediately put into concrete terms in the ban on images , which, according to both versions of the Decalogue, forbids both images of other gods and of one's own god. With this, YHWH's worship is definitively differentiated from all other cults. Because there the highest and only gods were always depicted and worshiped in images that represented their powers.

Images of God were not identified with the depicted God in Israel's neighborhood either and were often veiled in order to preserve transcendence . But the ban on images puts the invisible God against the gods tangible in the image, because for Israel he is the creator of all things and reserves the right to whom and how he reveals himself. This independence corresponds with YHWH's commitment to the liberation of his people. The memory of the Exodus, on the other hand, prevents it from being worshiped in the manner of foreign gods, who as a rule approved of domination. Israel's God does not want to be represented in cult, but to be worshiped in social behavior in all areas of life.

In both versions, the prohibited area extends to heaven, earth and the underworld, i.e. all "floors" of the worldview at that time. The Deuteronomic interpretation in Deut . 4, 12-20 EU reinforces the prohibition against depicting God as man, woman, animal, or celestial body, as was customary in the Canaanite fertility cults and Babylonian astral cults . Believing Jews, therefore, cannot consider anything in the world of created things to be divine. That is why they were later called "atheists" in Hellenism .

Since God revealed himself to Jews from the beginning through his - also exclusively intended - word ( Gen 1.3 EU ), the ban on images in the Tanach only affects optical and representational images, not language images. These show a great variety of metaphors , comparisons and anthropomorphisms .

Older forms such as Ex 34.12ff EU, with the exclusion of other gods, also command the destruction of their places of worship in Israel. This possibly reacted to the equations of YHWH with the Canaanite Baal in the image of the bull ( 1 Kings 12.26ff EU ), which stands behind the story of the golden calf in Ex 32 EU . Since the appearance of the prophet Elijah in the northern kingdom of Israel, this syncretism was understood as taking over the characteristics of Baal and was rejected ( 1 Kings 18 EU ). Also Hosea was fighting for the first commandment against "fornication" of Baalskultes ( Hos 8,4ff EU ; 10,5f EU ; 11.2 EU ; 13.2 EU ). But after Hezekiah's ( 2 Kings 18.4 EU ) failed attempts , it was only King Josiah who allowed the still existing Baal cults around 620 BC. Destroy (23 EU ). So the sole veneration of YHWH was enforced domestically.

In order to underline its weight, the ban on images is reaffirmed with a divine speech similar to the preamble. It therefore forms an indissoluble unity with YHWH's exclusive self-conception. Only then does the indicative encouragement ("I am ...") become an equally binding claim ("You should ...", literally "You will ...").

Apodictic legal propositions

The commandments to keep the Sabbath day and to honor the parents are followed by a series of apodictic - unfounded and categorical - formulated individual prohibitions. They generally exclude certain behavior without specifying the positively intended behavior, so they lay claim to collective and time-spanning validity. They are literally formulated as encouraging encouragement ("You will not ..."), thus expressing an unconditional confidence in the future in the addressees.

This distinguishes them from a large number of commands stemming from everyday jurisprudence for specific individual cases ( casuistry ). Such “if-then” regulations have models and parallels in the ancient oriental environment of Israel, for example in the Codex Hammurapi .

Contract form

William Sanford LaSor interprets the Sinai pericope (Ex 20-24) as the founding document of the covenant between YHWH and the people of Israel. The Decalogue is similar to a contract between a great king and his vassal that was customary at the time . Also Lothar Perlitt sees parallels to Hittite treaties which were imitated by the Israelites. From this he concludes that the text is very old.

LaSor finds the following similarities:

- The preamble names the federal donor and his titles.

- The prologue describes the earlier relationship between the contracting parties and emphasizes benefits that the great king bestowed on the vassal.

- The federal statute consists of:

- a. the basic requirement of federal loyalty

- b. detailed provisions. The obligations of the vassal to his great king are laid down in secular treaties.

- Further dispositions about:

- a. the deposit of the text. Federal texts are kept in the temple. The panels with the Federal text were in the ark to deposit.

- b. the repeated public reading of the federal text, to be carried out at regular intervals. This could have been carried out in pre-state Israel at tribal assemblies in Shechem ( Jos 24 EU ), later at the Jerusalem temple ( 1 Kings 8 EU ).

- Promises of blessings and threats of curse to be given to the vassal, depending on whether he complies with federal regulations or not. Biblically, these are not stated in the Decalogue, but twice in the further course of the Torah, namely in Lev 26 EU and Dtn 28 EU .

From this, LaSor concludes that the Decalogue was never conceived as a moral code, but as a regulation that regulates the covenant relationship and was set as a basic requirement for God's gracious care for the people of Israel. If the people fail to obey these commandments, they are breaking the covenant and, in a sense, ceasing to be God's people. The further history of Israel can also be understood from this context. The people keep moving away from YHWH; the latter then initiate a kind of legal process by first sending the prophets who call the people to repent for the last time and announce the impending judgment. Only then will he let his curse fall on the people.

Development process

The Ten Commandments came into being and grew together over centuries. In the beginning they were just one of several series of commandments, related in form and content, which summarized YHWH's will: Ex 34.17–26 EU , Lev 19.1f EU , 11–18 EU , Dtn 27.15–26 EU - a so-called Dodecalogue (twelve-word ), possibly based on the Twelve Tribes of Israel - and Ez 18.5–9 EU . The two versions of the Decalogue each contain twelve individual demands, but these are already referred to as “ten words” ( Ex 34.28 EU ) within the Torah and are divided accordingly. The oldest known Bible manuscript for the Decalogue, the Papyrus Nash (around 100 BC), attests to a mixed text of Ex 20 and Dtn 5.According to this, the Decalogue was not yet finalized at that time, but was used until the end of the Jewish Bible canon (around 100 BC) AD) further developed.

The first three commandments (according to Lutheran and Catholic counts) are formulated as a direct speech from God and are explained in detail (Ex 20: 2-6). The following brief and unconditional individual instructions (Ex 20.7–17) speak of God in the third person. Both parts therefore originated independently of one another, were subsequently linked to one another and finally put together under God's introductory self-conception. Only then did the “prohibitives” (absolutely excluding prohibitions), whose personal form of address was widespread in ancient oriental law, acquire the character of an all-Israelite federal law.

Similar self-conceptions of YHWH ( Hos 13.4 EU ; Ps 81.11 EU ) and series of criticisms of the standard of social commandments ( Hos 4.2 EU ; Jer 7.9 EU ) can be found in the prophecy in the Tanach . That is why a pre-form of the Decalogue, which contained the first commandment together with the exclusion of other gods and a few other commandments, dates back to the 8th century BC at the latest. Dated. The individual social commandments come from nomadic times (1,500–1,000 BC) and reflect their relationships: for example, the prohibition to covet cattle, slaves and wives of one's neighbor. They were specifically selected from many similar instructions to members of the clan in order to summarize God's will as universally as possible.

Since Ex 20 interrupts the narrative thread of the Torah, while Dt 5 connects the preceding and following Moser speech, the Ten Commandments could be quoted as an independent unit in different contexts. According to Lothar Perlitt , this unit was established by the authors of the Deuteronomic History in the 7th century BC. Created. But the exodus version of the Sabbath commandment alludes to Gen 2.2f EU , which is part of the priestly written account of creation: According to this, the first three commandments were probably not placed before an already existing series of prohibitions until the Babylonian exile (586–539 BC). Only the final editing of the five books of Moses put the existing series in front of the following corpora of law both times.

This gave the Ten Commandments their paramount importance as essential basic rules for all areas of life in the further history of Judaism and Christianity. Believing Jews and Christians regard them as the core and concentrate of God's revelation to Moses , the recipient and mediator of his will for the chosen people of God who has been called to be Israel's leader.

There are no extrabiblical parallels for the commandments of the cult tablet. In contrast, the social commandments of the Decalogue were compared with extra-biblical texts such as the "Negative Confession of Sin" (Chapter 125 in the Egyptian Book of the Dead , around 1500 BC), which was the basis of Porphyry's account of the Egyptian judgment of the dead : "I have the gods, those who my parents taught me have always been venerated in my life, and those who have given me life I have always cherished. But I have not killed any of the other people and have not robbed any of the goods entrusted to me, nor have I committed any other irreparable injustice ... "The rules indirectly presupposed here and their sequence (worship gods, honor father and mother, do not kill, do not rob, nothing else Committing injustice) already compared John Marsham, a 17th century Bible exegete, with the Decalogue. Earlier Old Testament scholars compared this directly with the 42 wrongdoings listed in the Book of the Dead. Because this contains no parallels to the commandment of sole worship, the sabbath rest and the ban on images, its text form is different and is in magical contexts, today's scientists like the Egyptologist Jan Assmann and the Old Testament scholar Matthias Köckert do not see it as a model for the Decalogue and the YHWH religion.

Classifications

Ex 20: 2–17 names neither the number of the commandment nor the tables; their identity with the "ten words" ( Ex 34.28 EU ) results from Dtn 4.12–13 EU ; 5.22 EU and 10.4 EU . The decalo speech, which has been handed down twice, contains eleven prohibition and two imperative sentences, whereby foreign gods, image and worship prohibitions as well as work and rest requirements appear as thematic units. From about 250 BC developed from this. Various attempts to divide the speech into ten individual commandments and thus to preserve the biblical ten norm. The ten number was also a learning and memory aid, since you could count the commandments on your fingers, and meaningful in magical number symbolism.

Even before the turn of the century, the biblically handed down mandatory tables caused the Decalogue to be divided into two parts, mostly into a "cult table" related to behavior towards God (self-conception up to the Sabbath commandment) and a "social table" related to behavior among one another (parental command to prohibition of desire).

Jews count YHWH's self-introduction in the first sentence according to the beginning of the Shema Yisrael prayer as the first, and the two following sentences together as the second commandment. In doing so, they follow the Talmud , which does not distinguish between a ban on foreign gods and a ban on images, but rather prohibits the worship of foreign gods depicted in cult images in accordance with Dtn 5.8 EU . What is exciting is that when counting the 613 rules of the Tanach in the “Decalogue” 14 commandments are identified.

Orthodox, Reformed and Anglicans, on the other hand, orient themselves towards Ex 20 and separate foreign gods and images, so that the latter also forbids images of one's own God. Like Jews, however, they combine the prohibitions against coveting another woman and foreign goods as one commandment.

Catholics and Lutherans count self-conception, foreign gods and images as a common first commandment. In doing so, they allow the ban on images to apply to their own god at best; many times it has been neglected as invalid for Christians. In order to preserve the ten number, they divide the prohibition of desire into two prohibitions, which they however order differently.The sixth commandment (prohibition of adultery) traditionally includes all violations of sexual morality , especially in Roman Catholic moral theology , including " fornication " and other sexual violations of rules within and outside of marriage.

| theme | Jews | Anglicans, Reformed, many free churches | Orthodox, Adventists | Catholics | Lutheran |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-introduction to YHWH | 1 | preamble | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ban on foreign gods | 2 | 1 | |||

| Ban on images | 2 | 2 | |||

| Name abuse ban | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Sabbath commandment | 4th | 4th | 4th | 3 | 3 |

| Parents command | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4th | 4th |

| Murder ban | 6th | 6th | 6th | 5 | 5 |

| Prohibition of adultery | 7th | 7th | 7th | 6th | 6th |

| Theft prohibition | 8th | 8th | 8th | 7th | 7th |

| Prohibition of false certificates | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8th | 8th |

| Prohibition of request | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 (woman) | 9 (house) |

| 10 (house and goods) | 10 (woman and goods) |

Interpretations

Judaism

Until 70 the Decalogue was read daily in the Jerusalem temple . It was also part of the Tefillin , according to some Dead Sea Scrolls and Samaritan inscriptions .

Philo of Alexandria wrote the treatise De decalogo around 40 . He saw it as the only direct revelation of God and divided it into two five commandments in order to make an analogy to the "eternal ideas" of Plato and ten categories of Aristotle . For him they were "main points" (basic principles) of all Torah commandments, indeed all laws in general, which he divided into ten subject groups assigned to each Decalogue commandment.

The rabbinate rejected such a priority of the Decalogue, and therefore also its daily reading to 100th It may have reacted to “minim” (primarily apostate Jews, in later rabbinical manuscripts also Jewish Christians ) who claimed: At Sinai God only revealed the Decalogue, all other commandments do not necessarily have to be obeyed. Nevertheless, after fragments from the Cairo Geniza , it remained part of the daily private Jewish morning prayer, where it is recited to this day.

In the Talmud collected rabbinical exegesis the particular importance of the first commandments in which God speaks to the people directly into I-shape emphasizes. She understood God's self-conception as an independent first, the prohibition of foreign gods and images together as the second and the prohibitions of desire together as the tenth commandment. Honoring the only liberating God corresponds to the rejection of all other gods who were usually worshiped in pictures. Important interpretations of the Decalogue were the Midrashim Mek , PesR (21–24) and Aseret Hadibberot (10th century). It was disputed whether the two surviving mandatory tables each contained half of the Decalogue or both contained the entire text. Since around 250 BC In the 4th century BC the Decalogue commandments were divided between the love of God and the love of one's neighbor , which were inscribed as equal, so that one could only love God by fulfilling the concrete social laws of the Torah. In the seventh and tenth commandments the others were seen as implied, since breaking them would inevitably lead to breaking the other commandments.

In the High Middle Ages , the differences between the wording in Ex 20 and Dtn 5 were explained speculatively: God or Moses had announced both versions at the same time, so both were equivalent. For Abraham ibn Ezra the slightly different words or letter combinations had the same meaning in each case; He explained larger additions in Deut. 5 than explanations supplemented by Moses. Nachmanides, on the other hand, saw Ex 20 and Deut 5 as the same divine speech handed down by Moses; it was preceded by the one in Ex 19.16-19 and Ex 20.18-21, followed by that in Dtn 5.22f. described popular reaction. In Ex 20 / Dtn 5 Isaac Abrabanel counted 13 individual commandments and understood the “ten words” according to Dtn 4,13; 10.4 therefore as speech sections. This reflected the masoretic accent systems : infralinear accents divided the text into ten, supralinear into 13 units. The former tended to be used for private, the latter for public worship readings.

Saadia ben Joseph Gaon , like Philo, saw all 613 Torah commandments included in the Decalogue. He poetically described the Decalogue commandments as their origin, tracing them back to 613 letters from Ex 20. He also adopted it in the liturgy of the Shavuot festival . Jehuda Hallevi called the Decalogue the "root of knowledge". Josef Albo understood the first table theologically, the second ethically, and both together as the main content of religion. Abraham bar Chija and similarly Samuel David Luzzatto divided the Decalogue and other Torah commandments into the three categories “God and man”, “Man and family”, “Man and fellow man”.

In Jewish Orthodoxy, the Decalogue is only read as part of a regular Torah section and at the Shavuot festival, with the congregation standing and listening. Maimonides contradicted this practice : People should not believe that one part of the Torah is more important than another. The Reform Judaism led the Dekaloglesung in the weekly Sabbath a -Gottesdienst.

New Testament

In the New Testament , the Ten Commandments are assumed to be the generally known and valid declaration of God's will for all Jews. They are therefore never repeated anywhere, but are quoted and interpreted individually on appropriate occasions.

According to the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus of Nazareth often quoted and interpreted individual Decalogue commandments. According to Mark 12: 28-34 EU, he followed up on the concentration of the entire Torah on the double commandment of love of God and neighbor, which had long been customary in rabbinic Judaism. By equating charity with the first commandment, he gave it priority over all individual commandments. The Torah sermons of the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5–7) compiled as “antitheses” comment on the Decalogue commandments “do not murder” (Mt 5.21 ff.), “Do not break marriage” (Mt 5.27 ff.) And indirectly “do not speak False testimony ”(Mt 5.33 ff.) In the sense of this supreme standard: They exacerbate it by already declaring the wrong inner attitude towards one's neighbor as a breach and offense against God. Hate murder, even a covetous look breaks marriage, every oath, not just perjury in court, is forbidden, since the confirmation of a statement in the oath implies that without it the statement could be a lie. In the Matthean composition of the Sermon on the Mount, these interpretations follow the "Beatitudes" to the people of the poor. These thus take the place of the “preamble” of the Decalogue. The unconditional promise of the kingdom of God to the poor updates the promise “I am YHWH, your God, who has liberated you from the land of Egypt”: God's past act of liberation corresponds to a coming liberation and the establishment of justice for all poor, like Judaism from the Messiah expected.

The compilation suggests that Jesus orally interpreted all ten commandments with a halacha, depending on the situation . An express commentary on the prohibition of foreign gods is his sermon on collecting supplies ( Mt 6 : 19–24 EU ). The accumulation of possessions and riches make them an idol ( mammon ) and stand in the way of the necessary sharing with the poor. This contradicts the love for God who loves the poor: "Where your treasure is, there is your heart ... No one can serve two masters." For the same reason, Jesus, like other Torah teachers at that time, ordered the Sabbath commandment according to Mk 2.27 EU Saving lives and healing people and allowed his followers to break the Sabbath in acute danger.

According to Mk 10.19 EU , he referred a wealthy landowner who asked him about the conditions for his entry into the kingdom of God to the Decalogue as the valid will of God, which the version Mt 19.18 f. supplemented with the reference to the commandment to love one's neighbor. The questioner lacks one thing in order to gain God's kingdom: giving up all property in favor of the currently poor (v. 21). The tenth commandment interprets this in the same way as the first: accumulating and clinging to wealth is robbery of the poor. What the Ten Commandments negatively exclude is given a positive direction through Jesus' call to discipleship : God's final will is not the preservation of an existing one, but the initiation of a new order in which the poor come to their rights.

According to Mark 3.35 EU , Jesus relativized the commandment of parental honor : "Whoever fulfills the will of God is brother and sister and mother for me." According to Mark 7.9-13 EU , however, he made it apply to Jews in general and against invalid vows that materially burdened the parents, affirmed. Since following Jesus included giving up family ties, early dispatching rules from the logia source demand the subordination of parents to love for God ( Mt 10.37 EU ) and even disregard for one's own relatives towards the love of Jesus ( Lk 14.26 EU ).

For Paul of Tarsus , Jesus Christ was the only person who fully fulfilled God's will. Salvation depends on his, not our, fulfillment; Anyone who continues to declare the Torah to be the way of salvation denies the salvation that God created for all people with the cross and resurrection of Jesus ( Letter to the Galatians ). As for Jesus, for Paul, charity also fulfills all the commandments of the Torah ( Gal 5,6 + 14 EU and Gal 6,2 EU ) and thus cancels them under certain circumstances. That is why the Torah commandments were given a new status for him: in particular the cult and sacrificial commandments, which, as a concretization of the first and second commandments in the Pentateuch, no longer played a decisive role for Paul. Cultic purity before God was not to be acquired through human effort, but was finally acquired through the atoning death of Jesus Christ.

In Romans in particular , Paul alluded to the social commandments of the Decalogue ( Rom 2.21f EU : seventh and sixth commandment; 13.9 EU : ninth and tenth commandment). By subjecting it to the commandment of the love of neighbor fulfilled by Jesus' gift of life, he generalized it: Love for the other replaces every “desire” (without a special object). Because this sin revealed Christ's way to the cross (7.7 EU ). The following sentence 13.10 EU (“love does no harm to one's neighbor”) refers back to the evil that the Roman state power inflicted on Christians and which they should counter with renunciation of force, beneficence and willingness to make sacrifices: “Do not let yourself be overcome by evil but overcome evil with good! ”(12.17–21 EU ). That is why the persecuted Christians should submit to the Roman state officials and pay them taxes (13.1ff EU ), but not conform to their pagan customs, but rather practice solidarity within the congregation in trust in God's final judgment (13.10-14 EU ). Your love of enemies should bring the Ten Commandments closer to the pagan environment as a reasonable ethic. This was possible for Paul because Christ gave his followers the Holy Spirit , who implanted the "law of life" into them and freed them from all mere letter faith for love (8.2ff EU ).

In Eph 6.2 EU , an early Christian house table justifies the warning to children to obey their parents with the fourth commandment. Jak 2,11 EU justifies God's election of the poor with the Decalogue and admonishes Christians: Breaking a single commandment already breaks God's entire will. Rev 9:21 EU alludes to the fifth to seventh commandments in the context of a vision of the final judgment. Thus the whole Decalogue remained valid for the early Christians.

Old church

Theologians of the early church such as Irenaeus of Lyons , Justin the Martyr and Tertullian saw the content of the Decalogue in agreement with the most important ethical principles known to man by nature. They established a tradition of interpretation that identified or analogized the Decalogue with natural law .

Augustine of Hippo, on the other hand, understood the Decalogue as the development of the double commandment to love God and neighbor. Accordingly, he assigned the first three commandments to love God and the other seven to charity. It was only through the love of Christ that the curse of the law, which exposes human sin , was turned into a gift of grace so that the Decalogue could become the norm of Christian life.

Roman Catholic Church

In scholasticism , the Decalogue was usually not interpreted as a whole, but rather individual Decalogue commandments within the framework of a doctrine of virtues . With Peter Lombardus and extensively with Thomas Aquinas , the Decalogue became the main component of their doctrine of the “law” in contrast to the doctrine of grace.

After the Council of Trent (1545–1563) the Decalogue became the basis for a Catholic moral teaching and examination of conscience , initially for the training of confessors . From then on, it remained a structure for binding ethical rules of life and Christian duties, with prohibitions being given greater weight. In doing so, these were detached from their historical context so that they appeared either as strict, unchangeable laws or as timeless and thus general norms that could be followed at will.

The Catholic Catechism quotes the first sentence, the ban on foreign gods and the ban on images together as the first commandment.

In the Catechism of the Catholic Church (KKK, 1st edition 1992), between paragraphs 2330 and 2331: “You should not commit adultery.” According to KKK 2351, unchastity and in 2352 masturbation are described as disordered or immature.

Protestant churches

Martin Luther's Great Catechism begins with the ban on foreign gods, which in itself appears as the first commandment. Then the second commandment is the prohibition of name abuse. His Small Catechism, on the other hand, cites self-conception and the prohibition of foreign gods together as the first, and the prohibition of name abuse as the second commandment. Luther does not name the ban on images directly, either in the large or in the small catechism. Lutherans follow Ex 20 EU and differentiate within the prohibition against coveting property of others between the first-mentioned “house” and the other goods, which include the “wife”, servants and animals. The two prohibitions here each form their own, the ninth and tenth commandments.

Anglicans and Reformed , like the Jews, follow the Exodus version of the Decalogue. They see God's self-conception as a “preamble” to all of the following commandments. The Reformed and Seventh-day Adventists separate the ban on foreign gods and the ban on images. Therefore all pictures are missing from them, not only pictures of gods in the worship room. Anglicans and Reformed Christians refer the tenth commandment to the “house” of their neighbor, which in biblical usage also encompasses all family attachments and property.

Due to the coincidence of these two deviations at the beginning and the end of the Decalogue, a total of ten commandments result in both versions, although the numbers of all commandments in between differ. The second to eighth commandments of the Lutheran / Catholic enumeration correspond to the third to ninth commandments of the Reformed / Jewish enumeration. So what z. For example, what is meant by a "violation of the fourth commandment" depends on whether you are speaking from a Reformed or Lutheran perspective.

As a result of the union of Lutherans and Reformed in numerous German regional churches, which therefore describe themselves as uniate , the question of which version of the Decalogue applies, often also has to consider a different denomination within the regional church. On the other hand, the Evangelical Church of the Palatinate , founded in 1818, decided in favor of a particularly extensive approval , whose unification charter has simply stipulated since 1818 to keep the Lutheran and Reformed confessional writings "with due respect".

The Pentecostal Movement , the Charismatic Movement , Evangelical and Free Church Christians emphasize that the Ten Commandments can only be obeyed completely or not at all. In doing so, they reject a "secular" takeover, interested only in the social laws, without belief in the person who, according to the Bible, issued the commandments and demands their entire observance. However, this also goes hand in hand with a certain conservatism in the interpretation of individual commandments.

The liberal theology emphasized often following a spiritualizing interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount, it'll be in all the commandments less on the wording as on the inner attitude.

Modern interpretations

In modern times , the Decalogue was understood as a timeless cultural heritage and the basis of autonomous ethics, i.e. ethics based on one's own insight, and translated into generally understandable rules of reason such as the categorical imperative . Outside of the Christian churches, the ten commandments in Europe are often understood as an “ethical minimum”, whereby this classification is more related to the commandments of the social table related to fellow human beings than to the cult table with its special reference to God . In addition, only a minority of the Western European population knows their wording, while Christians in the USA and in a minority situation ( diaspora ) are often very familiar.

In the time of National Socialism , the Ten Commandments were sometimes the basis for church contradictions to social developments. For example, on September 12, 1943, the German Catholic bishops published a “ pastoral letter on the Ten Commandments as the law of life of the peoples”, in which they protested against the mass murders of the National Socialists at the time :

"Killing is inherently bad, even if it is supposedly carried out in the interest of the common good: on the guilty and defenseless mentally weak and sick, on the incurably sick and fatally injured, on hereditary and unfit for life newborns, on innocent hostages and disarmed war or Prisoners, people of foreign races and origins. Even the authorities can and must only punish crimes that are really worthy of death with death. "

reception

Legal history

Little research has been done on the influence of the Decalogue on European legal history. In the biblical context, it forms a kind of draft constitution for a popular community that sees itself as being constituted by an internal historical experience of liberation and therefore committed to its God. From this, the Decalogue derives basic rules for this community and each of its members, which should remain binding for every form of society.

Mediated through church history, the Decalogue had less of a societal effect, but rather continued to act individually as the epitome of so-called Christian virtues . There are therefore only a few historical examples of the direct influences of the Decalogue on material law: for example the late antique Collatio legum Mosaicarum et Romanorum (around 390), which assigned Roman legal clauses to the Decalogue , or the medieval laws that Alfred the Great (approx. 849– 899) each introduced with a paraphrase of the corresponding Decalogue.

Even the Roman emperor Julianus pointed out in 363 that the commandments of the “cult table” (ban on foreign gods, implicit sanctification of names, and the Sabbath command) are not capable of consensus, while hardly any people would reject the other commandments. Modern legal history has been interpreted as an attempt to establish precisely this reasonable legal consensus, without generally demanding belief in the giver of these basic rules, which are indispensable for living together. Today some Old Testament scholars and historians point out that although modern human rights were formulated and enforced against the theocratic claim to validity of the Decalogue, they were nonetheless laid out in and influenced by it. For example, the constitutional theory of the theologian Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès was influenced by biblical law in the French Revolution . The specifically Jewish Sabbath commandment had concrete legal and social-historical consequences in the form of the general statutory Sunday rest.

In the USA , the relationship between biblical legal tradition and the basic principles of the US constitution is still controversial today. Attempts by conservative Christians to gain public attention and validity for the Decalogue, for example in state authorities, schools, and courthouses, have resulted in several model trials and fundamental judgments by the Supreme Court since 1945 . The philosopher Harry Binswanger , chairman of the Ayn Rand Institute, is a representative of a consistent exclusion of the Decalogue from the public : He sees the first three commandments of the Decalogue as calls for subordination, which could not reasonably justify the meaningful contents of the social commandments, as this would Contradicts the human right to individual self-determination.

Fiction and popular religious literature

In 1943, Thomas Mann wrote a novella in English in the USA for the anthology The Ten Commandments , which he translated into German in 1944 and published under the title Das Gesetz in Stockholm. It describes the emergence of the Ten Commandments as a novel as a guide to the incarnation of man: quoted from Karl-Josef Kuschel: Global ethic from a Christian perspective (April / May 2008)

“The Jews gave the world the universal God and - in the ten commandments - the basic law of human decency. That is the most comprehensive thing that can be said of their cultural contribution ... "

Although they only address Israel, they are "a speech for all" whose universal validity every listener can understand directly. Mann pointed out their opposition to National Socialist barbarism, which at that time tried to override any general foundation of humanity and morality:

"But curse the person who gets up and says: 'They are no longer valid.'"

In 2011, the Catholic theologian Stephan Sigg published a book for young people, “10 Good Reasons for God - The 10 Commandments in Our Time” , which aims to bring the Ten Commandments closer to young people. Borromäusverein and Sankt Michaelsbund chose the book as “religious children's book of the month” for April 2011 with the reasoning: “The stories are entertainingly told with a lot of irony and humor, but always without a pedagogical finger and an instructive undertone. With their mostly subtle references to the Ten Commandments, they provoke the reader to think. "

In the novel The Discovery of Heaven , Harry Mulisch tells of a search for the tablets of the law.

music

- Johann Sebastian Bach wrote two parts of his keyboard exercise part III on Luther's song These are the sacred ten commandments .

- The church musician Karl Maria Doll wrote an oratorio The Ten Commandments for the Luther year 1995 .

- A pop oratorio “ The 10 Commandments ” by musical writer Michael Kunze and composer Dieter Falk was premiered on January 17th, 2010 in the Westfalenhalle Dortmund.

- Die Toten Hosen released a song called The Ten Commandments on Opium fürs Volk in 1996 .

- The music project E Nomine brought out the piece of music The 10 Commandments with Christian Brückner as speaker.

- Jürgen Werth wrote the song Ten Life Offers , which describes the 10 commandments as a liberating guide to life.

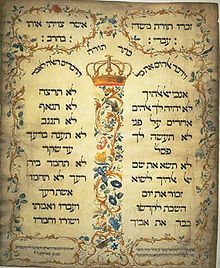

photos

God's handing over of the stone tablets to Moses, rarely with the entire Torah (Ex 24.12), mostly with the Ten Commandments (Ex 34.28), has been a standard motif in Christian art since the 6th century, especially in Byzantine iconography and illustrated Bible manuscripts from the High Middle Ages , later also in printed works. A famous example is the apse mosaic in St. Catherine's Monastery (Sinai) . Most of these depictions typify Moses as the humble recipient of the tablets from God's hand, sometimes combined with the motif of the burning bush as a symbol of his calling , while the Israelites almost never appear. A picture of Moses is often juxtaposed with a picture of Jesus Christ , so that the receipt of the Decalogue should apply to all peoples and point to the fulfillment of the Torah by the Son of God .

Lucas Cranach the Elder created a large mural for the courtroom in Wittenberg in 1516 . Ten image fields show the relevance of a commandment in everyday life. All partial images are vaulted with a rainbow reminiscent of the covenant promise of Gen 9. This interpreted the Decalogue as God's universal law for mankind saved from destruction, on which all concrete legislation and jurisprudence is based.

Many artists depicted the smashing of the tablets of the law by Moses, including Raphael (frescoes in the loggias of the papal palace in the Vatican), Nicolas Poussin , Rembrandt ( Moses smashes the tablets of the law ), Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and Marc Chagall ( Moses breaks the tablets of the law , 1955 -1956). The handover of the tablets of the law was depicted, among others, by Cosimo Rosselli in a mural in the Sistine Chapel and again by Chagall several times.

The decalogue tables in Huguenot churches often served as a substitute for pictorial representations.

Sculptures

In anti-Judaistic sculptures of the Ecclesia and synagogue in and on churches of the High Middle Ages, the figure of the synagogue is depicted with blindfolded eyes and tablets of the law.

Around 1890, the city of Bremen had the Ten Commandments affixed as mosaics on the outer facade of the Bremen regional court building below the window parapets of the room in which the jury court sat. The National Socialists banned the typefaces, whereupon the citizens of Bremen covered them up with stone tablets instead of destroying them as requested.

In Austin , Texas, stelae bearing the Ten Commandments were erected in front of the House of Parliament in the 1960s . While similar monuments in front of courthouses in the United States have been banned and removed in most states due to the constitutional separation of religion and state, the Supreme Court found in this case that the steles could remain as a general historical work of art.

Movies

The subject of the biblical Ten Commandments has been filmed several times. Cecil B. DeMille was the director of two monumental films: The Ten Commandments (1923) and The Ten Commandments (1956) . The television re-filmed this film material: The Ten Commandments (2006) . Krzysztof Kieślowski created the ten-part film cycle Dekalog , which updated each individual bid with a contemporary story. He also wrote the script for a play with Krzysztof Piesiewicz. In 2007 the film comedy Das 10 Gebote Movie was released as a parody of the Ten Commandments.

See also

literature

overview

- Lothar Perlitt , Jonathan Magonet , Hans Hübner , Hans-Georg Fritzsche , Hans-Werner Surkau: Decalogue . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 8, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008563-1 , pp. 408-430.

- Wilhelm Lotz: Decalogue . In: Realencyklopadie for Protestant Theology and Church (RE). 3. Edition. Volume 4, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1898, pp. 559-564.

- Matthias Köckert : The Ten Commandments. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-406-53630-1 .

Biblical studies

- Dominik Markl: The Decalogue as the constitution of the people of God. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2007, ISBN 978-3-451-29475-4 .

- Christian Frevel et al. (Ed.): The ten words. The Decalogue as a test case of the Pentateuch criticism. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2005, ISBN 3-451-02212-5 .

- Innocent Himbaza: Le Décalogue et l'histoire du texte. Études des formes textuelles du Décalogue et leurs implications dans l'histoire du texte de l'Ancien Testament. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-53065-X .

- Pinchas Lapide : Is the Bible Translated Correctly? , Gütersloher Verlagshaus 2004, ISBN 978-3-579-05460-5 .

- Timo Veijola : Moses' heirs. Studies on the Decalogue, Deuteronomism and scribes. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-17-016698-0 .

- Christoph Dohmen : What was on the tablets of Sinai and what was on those of Horeb? In: Frank-Lothar Hossfeld: From Sinai to Horeb. Stations in the history of the Old Testament faith. Echter Verlag GmbH, 1998, ISBN 3-429-01248-1 , pp. 9-50.

- Frank Crüsemann : Preservation of Freedom. The theme of the Decalogue from a socio-historical perspective. Christian Kaiser Verlag, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-459-01518-7 .

- Frank-Lothar Hossfeld: The Decalogue. Its late versions, the original composition and its preliminary stages. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1982, ISBN 3-525-53663-1 .

- Frank-Lothar Hossfeld: “You shouldn't kill!” The fifth Decalogue in the context of Old Testament ethics. Contributions to the ethics of peace 26, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-014410-3 .

- Hartmut Gese : The Decalogue viewed as a whole. In: Hartmut Gese: From Sinai to Zion. Old Testament contributions to biblical theology. Munich 1974, ISBN 3-459-00866-0 , pp. 63-80.

Judaism

- Henning Graf Reventlow (Ed.): Wisdom, Ethos and Commandment. Wisdom and Decalogue Traditions in the Bible and Early Judaism. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2001, ISBN 3-7887-1832-3 .

- B.-Z. Segal: The Ten Commandments in History and Tradition. Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem 1990, ISBN 965-223-724-8 .

- Günter Stemberger : The Decalogue in early Judaism. JBTh 4/1989, pp. 91-103.

- Horst Georg Pöhlmann, Marc Stern: The Ten Commandments in Jewish-Christian Dialogue. Their meaning and importance today. A little ethic. Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-87476-372-2 .

Christianity history

- Dominik Markl (ed.): The Decalogue and its Cultural Influence (Hebrew Bible Monographs 58), Sheffield Phoenix Press, Sheffield 2013, ISBN 978-1-909697-06-5 .

- Ludwig Hödl: Article Decalogue ; in: Lexicon of the Middle Ages , Volume 3; Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2002; ISBN 3-423-59057-2 ; Sp. 649-651

- Hermut Löhr: The Decalogue in earliest Christianity and its Jewish environment. In: Wolfram Kinzig , Cornelia Kück (Hrsg.): Judaism and Christianity between confrontation and fascination. Approaches to a new description of Judeo-Christian relations (Judaism and Christianity 11); Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 2002; Pp. 29-43.

- Jörg Mielke: The Decalogue in the legal texts of the Western Middle Ages. Scientia Verlag, Aalen 1992, ISBN 3-511-02849-3 .

- Guy Bourgeault: Décalogue et morale chrétienne. Desclée Bellarmin, Paris / Montreal 1971.

- Jean-Louis Ska: Biblical Law and the Origins of Democracy. In: William P. Brown (Ed.): The Ten Commandments: The Reciprocity of Faithfulness. Westminster Press, Louisville 2004, ISBN 0-664-22323-0 , pp. 146-158.

Theological ethics

- Fulbert Steffensky : The Ten Commandments, instructions for the land of freedom. Echter, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-429-02512-5 .

- Hermann Deuser : The ten commandments. Small introduction to theological ethics. Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-018233-6 .

- Traugott Giesen: Act like this, and you will live. The Ten Commandments. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-70347-6 .

- Traugott Koch: Ten Commandments for Freedom. A little ethic. Mohr, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-16-146372-2 .

- Heinrich Albertz (Ed.): The Ten Commandments. A series of thoughts and texts. 10 volumes, Radius, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-87173-789-5 .

- Rupert Feneberg , Wolfgang Feneberg : When we hear: I am your God. Parish Catechism II. The Ten Words from Sinai. Herder Verlag GmbH, Freiburg 1986, ISBN 3-451-19610-7 .

Present-day interpretations

- Günther Beckstein : The ten commandments: aspiration and challenge. Holzgerlingen: SCM, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7751-5191-7 .

- Mathias Schreiber : The Ten Commandments: An Ethics for Today - A SPIEGEL Book. 2nd edition, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2010, ISBN 3-421-04486-4 .

- Lothar Gassmann: The Ten Commandments of God. How can we live after that? Samenkorn-Verlag, Steinhagen 2009, ISBN 978-3-936894-78-3 .

- Notker Wolf, Matthias Drobinski : Rules for life: The Ten Commandments - Provocation and orientation for today. Herder, 2nd edition, Freiburg 2008, ISBN 3-451-03017-9 .

- Bernhard G. Suttner: The 10 Commandments: An ethic for everyday life in the 21st century. Mankau, 2007, ISBN 3-938396-14-8 .

- Hans Joas: The Ten Commandments: A Contradictory Legacy? Böhlau, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-412-36405-3 .

- Reimer Gronemeyer: Ice Age of Ethics. The Ten Commandments as border posts for a humane society. Echter, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-429-02528-1 .

- Erwin Grosche, Dagmar Geisler: Felicitas, Mr. Riese and the Ten Commandments. Gabriel Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-522-30033-5 (for children).

- Christiane Boos: Me, the next one and what else counts. The Ten Commandments as offers. Stories for teenagers. Lutheran Publishing House, 2002, ISBN 3-7859-0860-1 .

- Hansjörg Bräumer : The gateway to freedom. The Ten Commandments, designed for today. Hänssler, 2000, ISBN 3-7751-3510-3 .

- Susanna Schmidt (Ed.): Impetus for happiness - What the Ten Commandments can mean today. Schwabenverlag, 2000, ISBN 3-7966-1000-5 .

- Wolfgang Wickler: The Biology of the Ten Commandments. Why nature is not a role model for us. Revised new edition, Piper, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-492-11361-3 .

- Johannes Gründel : The Ten Commandments in Education. For parents and educators. Rex-Verlag, Lucerne 1992, ISBN 3-7926-0057-9 .

- Armin L. Robinson: The Ten Commandments. Hitler's war on morality. Fischer TB, 1988.

- Johanna J. Danis : The "Ten Words". Edition Psychosymbolik, 1987, ISBN 978-3-925350-16-0 .

art

- Veronika Thum: "The Ten Commandments for the Unlearned People". The Decalogue in the Graphics of the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Times. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-422-06637-3 .

- Klaus Biesenbach (ed.): The ten commandments. An art exhibition. German Hygiene Museum, Dresden / Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2004, ISBN 3-7757-1453-7 .

literature

- Sibylle Lewitscharoff, Walter Thümler and David Wagner, Uwe Kolbe u. a .: Decalogue today. 21 literary texts on 10 commandments . Ed .: Ludger Hagedorn, Mariola Lewandowska. 1st edition. Herder, Freiburg 2017, ISBN 978-3-451-37786-0 .

music

- Paul G. Kuntz: Luther and Bach: Your setting of the Ten Commandments. In: Erich Donnert (Hrsg.): Europe in the early modern times. (Festschrift Günter Mühlpfordt), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 978-3-412-10702-4 , pp. 99-106.

- Luciane Beduschi: Joseph Haydn's The Sacred Ten Commandments as Canons and Sigismund Neukomm's The Law of the Old Covenant, or the Legislation on Sinaï: Exemplification of Changes in Musical Settings of the Ten Commandments during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. In: Dominik Markl (Ed.): The Decalogue and its Cultural Influence (Hebrew Bible Monographs 58); Sheffield Phoenix Press, Sheffield 2013, ISBN 978-1-909697-06-5 ; Pp. 296-317.

Web links

- The Ten Commandments (based on Martin Luther's Small Catechism)

- Luchoth haBrith: The Ten Commandments. In: haGalil . (with Buber-Rosenzweig translation).

- A Brief Introduction to the Origin of the Ten Commandments. (pdf, 208 kB) In: Unser-zehn-gebote.de. March 9, 2006, archived from the original on March 5, 2016 (EKD teaching material).

- Matthias Köckert: Decalogue / Ten Commandments. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Series of sermons on the Ten Commandments. Melanchthon Academy, September 11, 2005 - April 30, 2006, archived from the original on January 1, 2011 .

- Till Magnus Steiner: Dossiers: The Ten Commandments. In: kathisch.de .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Viola Hildebrand-Schat: The Danziger commandments tables as a mirror of their time . Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici (2011)

- ↑ Often translated as "You shouldn't kill". In addition: Elieser Segal: The Sixth Commandment: You shall not murder ... Jüdische Allgemeine , November 9, 2006, accessed on November 9, 2015.

- ↑ Michael Konkel: What did Israel hear on Sinai? Methodological notes on the context analysis of the Decalogue. In: Michael Konkel, Christoph Dohmen and others (eds.): The ten words: The Decalogue as a test case of the Pentateuch criticism. Freiburg im Breisgau 2005, pp. 19-30.

- ↑ Quoted from Shalom Ben-Chorin: Praying Judaism: The Liturgy of the Synagogue. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1980, ISBN 3-16-143062-X , p. 159

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Old Testament Faith in its History. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, ISBN 3-7887-1263-5 , p. 61.

- ↑ In the period around 1550 came in Calvinist dominated areas of northern Germany Scripture altars upon which are designed biblical and liturgical texts artistically and instead of images in churches were attached.

- ^ Dietrich Diederichs-Gottschalk : The Protestant written altars of the 16th and 17th centuries in northwest Germany . Verlag Schnell + Steiner GmbH, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-7954-1762-8 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Old Testament Faith in Its History , Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, p. 83 ff.

- ↑ Georg Fischer, Dominik Markl: The book Exodus. New Stuttgart Commentary Old Testament. Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-460-07021-9 , p. 220

- ↑ William Sanford LaSor include: federal and Law at Sinai. In: The Old Testament. Brunnen, Giessen 1989; Pp. 167-172.

- ↑ Lothar Perlitt , Jonathan Magonet , Hans Hübner , Hans-Georg Fritzsche , Hans-Werner Surkau: Decalogue I . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 8, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008563-1 , pp. 408-413.

- ^ Porphyrius: De Abstinentia IV, 10; Quote from Jan Assmann: Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Beck, Munich 2001, p. 112ff.

- ^ John Marsham: Canon chronicus Aegyptiacus, Ebraicus, Graecus , 1672; Digitized, there p. 156f. ; various reprints.

-

↑ Examples: Burkard Wilhelm Leist: Graeco-Italische Rechtsgeschichte. Jena 1884, p. 758 ff.

Rudolf Kittel: Geschichte des Volkes Israel , Volume 1, Klotz, 6th edition, Gotha 1923, p. 445 f. -

↑ Jan Assmann: The Decalogue and the Egyptian norms of the judgment of the dead. In: World and Environment of the Bible 17 (2000), pp. 30–34.

Matthias Köckert: Decalogue / Ten Commandments. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Hrsg.): The scientific Bibellexikon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on November 9, 2018. There: 1.2. Form and function. - ↑ M. Köckert: Decalogue (Wibilex) . In: https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/10637/ . S. Section 1.3 .

- ↑ Bo Reicke: The ten words in the past and present: Counting and meaning of the commandments. Mohr / Siebeck, Tübingen 1973, p. 21 ff.

- ^ Johann Maier: Studies on the Jewish Bible and its history. (2004) De Gruyter, Berlin 2013, ISBN 3110182092 , p. 419 ; Udo Schnelle: Antidocetic Christology in the Gospel of John: An investigation into the position of the fourth gospel in the Johannine school. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1987, ISBN 3525538235 , p. 40

- ↑ J. Cornelis Vos: Reception and effect of the Decalogue in Jewish and Christian writings up to 200 AD. Brill, Leiden 2016, ISBN 9004324380 , p. 364

- ^ Günter Stemberger: Decalogue III: Judaism . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 3 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, Sp. 65 .

- ↑ Christoph Dohmen: Exodus 20: 1–21: The Decalogue , in: Christoph Dohmen, Erich Zenger: Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament: Exodus 19–40. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2004, ISBN 3-451-26805-1 .

- ↑ Günter Stemberger: The Decalogue in Early Judaism , JBTh 4/1989, p. 103.

- ↑ Jonathan Magonet: Dekalog II , in: Theologische Realenzyklopädie, Volume 8, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 413f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stegemann: The Gospel and the poor. Christian Kaiser, Munich 1981, p. 41.

- ^ Hans Huebner: Decalogue III: New Testament ; in: Theologische Realenzyklopädie Volume 8, 1981; ISBN 3-11-008563-1 ; Pp. 415-418.

- ↑ Dieter Singer: Decalogue III: New Testament , in: Religion in Past and Present Volume 2, 4th Edition, Column 630.

- ↑ Johannes Gründel: Decalogue IV . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 3 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, Sp. 66 f .

- ↑ Catholic Catechism: The Ten Commandments

- ^ The Great Catechism of Martin Luther ( Memento of January 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The Small Catechism of Martin Luther ( Memento of February 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Klaus Bümlein: The history of the Evangelical Church of the Palatinate from the Union 1818 to today. Evangelical Church of the Palatinate (Protestant Church), accessed on May 13, 2018 (paragraph 6).

- ↑ Kirchengeschichte.de: The Catholics and the Third Reich, 4. The war years

- ↑ On the importance of the Decalogue for the systematics of criminal offenses: Hellmuth von Weber: The Decalogue as the basis of the criminal system. In: Festschrift for Wilhelm Sauer on his 70th birthday on June 24, 1949, Berlin 1949, pp. 44–70.

- ^ Karl Leo Noethlichs: The Jews in the Christian Roman Empire. (4th-6th centuries). Akademie-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-05-003431-9 , p. 200

- ↑ Dominik Markl: The Decalogue as a constitution of the people of God. Freiburg im Breisgau 2007, p. 283f.

- ^ Georg Braulik: Deuteronomy and human rights. In: Theologische Viertelschrift 166/1986, pp. 8–24; also in: Gerhard Dautzenberg , Norbert Lohfink , Georg Braulik : Studies on the Methods of Deuteronomy Exegesis: Volume 42. Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-460-06421-8 , pp. 301–323.

- ↑ Thomas Hafen: State, Society and Citizens in the Thought of Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes. Bern 1994, ISBN 3-258-05050-3 .

- ^ Jürgen Kegler: Sabbath - Sabbath rest - Sunday rest. A theological contribution to a current discussion. In: Jürgen Kegler (ed.): That justice and peace kiss: collected essays, sermons, radio speeches. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-631-37140-3 , pp. 147-170.

- ↑ Lucy N. Oliveri: Ten Commandments: Supreme Court Opinion and Briefs with Indexes. Nova Science Publications, 2005, ISBN 1-59454-657-6 .

- ↑ Ainslie Johnson: The Ten Commandments versus America. In: objektivisten.org. February 2, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Ed. Armin L. Robinson. Other contributors are Rebecca West , Franz Werfel , John Erskine , Bruno Frank , Jules Romains , André Maurois , Sigrid Undset , Hendrik Willem van Loon and Louis Bromfield . French edition Les dix commandements, published by Michel, Paris 1944, after the liberation. Other individual contributions from it have been partially translated into German, e. B. Maurois, The Singer , in: Carl August Weber Ed .: France. Poetry of the Present Weismann, Munich 1947 p. 32.

- ^ Matthias Köckert: The Ten Commandments , CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 8.

- ↑ Sigg, Stephan: 10 good reasons for God. The Ten Commandments in our time. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011 ; Retrieved July 4, 2011 .

- ↑ Religious Children's Book of the Month April 2011. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011 ; Retrieved July 4, 2011 .

- ↑ The 10 commandments are suitable for everyday use. Retrieved July 4, 2011 .

- ↑ Ten Life Offers . ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Text of the song by Jürgen Werth, accessed on November 9, 2015.

- ^ Theologos Chr. Aliprantis: Moses on Mount Sinai. The iconography of the calling of Moses and the reception of the tablets of the law. Tuduv-Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1986; ISBN 3-88073-209-4 ; Pp. 33-39 and 79-92.

- ↑ a b Matthias Köckert: The Ten Commandments , CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Heinrich Krauss, Eva Uthemann: What pictures tell: The classic stories from antiquity and Christianity. Beck, Munich 2011, p. 210f.

- ↑ Andreas Flick: The Ten Commandments as decoration in German Huguenot churches. In: Reformiert 2002, no. 3, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Matthias Köckert: The Ten Commandments , CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 10.