Judgment of the dead

Judgment of the dead (or judgment of the hereafter ) describes the religious conception according to which the human being is placed before a divine or otherworldly body that judges his or her lifestyle. This can happen immediately after death or already during lifetime ( eschatologically ), in some religions in both ways. The assessment is mostly based on ethical standards. However, social criteria or death rituals can also play a role. In a broader sense, the term refers to all selection processes that a person has to go through after their death. Often the judgment of the dead coincides with the last judgment at the end of the world.

Essential basic terms and concepts

The forms of the judgment of the dead and the associated conceptions of the afterlife reflect a certain understanding of the world. The following concepts and influencing factors are essential:

-

Primary influencing variables (often combined with one another)

- Ancestor cult in which the idea of a continuum of this world and the hereafter predominates.

- Cult of the dead and funeral cult . One speaks of the cult of the dead when death itself is the focus of the rites and no longer the relationship to the ancestors. There is a dualism between this world and the hereafter.

- Last judgment with notions of end times ( eschatology ). As a rule, one imagines the world to be linear (rarely cyclical), at the end of which there is the judgment of the dead.

-

Religious and cosmological concepts

- Death and immortality

- Relationship between this world and the hereafter , between the underworld / realm of the dead and heaven

- Ideas of god / gods, spirits and demons

- Ideas of karma , grace , guilt , salvation , predestination , etc.

The more philosophical concepts such as the worldview , ethics and morals , conscience and free will , as well as the notions of responsibility , guilt (ethics) and justice also have an influence . As more social concepts play the social status , the social structure , law and law , v. a. the principle of retribution , and finally the rituals and sacrifices as well as the forms of burial and grave goods play a role.

Judgments of the dead in different religions and cultures

Preliminary remarks

Judgments of the dead and with them the notions of end-time events ( eschatology ) are often a fundamental and complex element of numerous religions. A purely historical description along the time axis only results in loosely connected partial views. Therefore a sociological , phenomenological and anthropological consideration is worthwhile . If one wants to understand a religion's judgment of the dead, one must understand its belief in the hereafter and its ethics.

Fundamental to understanding the concept of the “judgment of the dead” is the idea of justice , which is initially traced back to divine origin. Notions of a restoration of justice in the other world through a judgment of the dead can first be demonstrated in the Mediterranean and Indo-European regions. People are judged based on religious, ethical and social criteria. Injustice committed or suffered is redressed, often in accordance with local legal norms. This occurs in stratified societies with hierarchical claims to power and often goes hand in hand with established religion. The justifications for the respective social order were initially metaphysical, later pseudorational, and useful for those in power.

This gave rise to the problem of theodicy (God's righteousness), which theologians and philosophers are concerned with to this day and which is not solved by any afterlife judgment, namely the problem of why evil has come into the world despite divine omnipotence and so much calamity there despite all sacrifices and prayers causes. In most cases it is not taken into account that good and bad can largely be determined relative to religion, society and culture as an expression of power and interests. In some religions, this divine omniscience and omnipotence appears in its most extreme form as the doctrine of predestination . Nevertheless, etc. was dead court be established here with hell, heaven, the Apocalypse, although this only makes sense if people with a free will and conscience are equipped so they for good or evil decide to. In Eastern religions, however, even the gods are subject to the law of karma . They are only part of an all-embracing cosmic harmony that is to be striven for - especially in Daoism .

The tension between free will (or conscience) including the longing for redemption on the one hand and the divine claims on the other essentially determines the design of the judgments of the dead. According to the legal theorist Hans Kelsen, people look for “absolute justification” in religion and metaphysics. This means, however, that justice must be transferred from this world to a hereafter, whereby a superhuman authority or a deity becomes responsible for absolute justice.

Historical religions

The idea of a judgment of the dead can first be clearly demonstrated in Egyptian mythology . SA Tokarev noted that consoling hopes for a reward in the afterlife were just as lacking in early class societies as they were in the " primitive society " in the early religions. Tokarev saw them as a necessary means to defuse intensifying class antagonisms. The goal of salvation is achieved in three main ways:

- In the oldest forms of belief mainly through magical rituals , e.g. B. in the ancient Egyptian religion and in the ancient mystery cults .

- Later through one's own efforts , usually through the acquisition of esoteric knowledge, asceticism or heroic death, for example in Orphicism , Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam as well as Zoroastrianism, but partly also in the religion of the Teutons ( Valhalla ) and the Greek concepts of Elysion .

- Finally through divine help , for example in Christianity (especially in the doctrine of justification ), in Judaism (especially in the later, post-exilic) and in Islam, which are therefore also called religions of salvation (for Buddhism, which is sometimes included, the motif of divine salvation through grace just not).

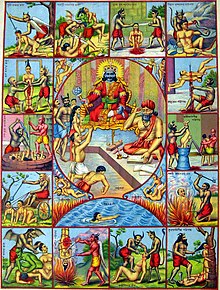

These forms are seldom pure. Over the years, mostly mixed forms have emerged from the three main forms, e.g. B. a funeral judgment in Hinduism, Buddhism and the Chinese ancestral religions, predestination and magical rituals in Islam, transmigration of souls in Orphic and Jewish Hasidism , etc. In younger religions we often come across customs from older religious traditions.

The limiting factor in the assessment of older religions is the tradition that is usually only archaeological and its scientific interpretation. In the following, the note “no judgment of the dead”, especially in the case of the early historical religions, does not mean that there actually was none, but only that none of it has been handed down (e.g. with the Phoenicians ). For the pre-classical high cultures, however, more detailed written documents have been preserved, especially in Egypt and Mesopotamia, in other cultures, such as early Vedic Hinduism , there are relevant religious or sacred texts.

Old Egypt

In ancient Egypt, the judgment of the dead, including images of the afterlife, can be demonstrated in detail for the first time. The "idea of a judgment of the dead" already emerged in the Old Kingdom and is attested in the pyramid texts in connection with the royal ascent into heaven . The idea of the judgment of the dead was initially limited to the king ( Pharaoh ) himself and his closest confidants. His invocation represented a danger, as a "request to review the deeds" in the case of the king's misconduct resulted in a negative judgment, which not only prevented the ascension of heaven, but also led to an eternal stay in the "hidden realm of death".

It was only in the course of the Middle Kingdom that the new theological concept of the third level ( Duat ), also in the private sphere, after successful examination by the judgment of the dead, reunited the Ba soul, which appears mainly in the form of a bird, as the bearer of the immortal forces in the hereafter with the body of the Dead, which was therefore to be preserved as a mummy .

The Judgment of the Dead (also Hall of Complete Truth ), which was modified in the New Kingdom and before which every non-royal deceased had to appear, was given canonical regulations and precise framework conditions for the first time . Now every ancient Egyptian knew in advance what “charges” awaited him and life before death could be adapted to the laws of the court of death. The judgment of the dead consisted of a tribunal, led by Osiris , of 42 judges (Gaugötter), some of whom were demonically understood , who decided which Ba souls were allowed to enter the afterlife . If the heart of the deceased and the goddess Maat, symbolized as a feather, were in balance, the deceased had passed the test and was brought by Horus to the throne of Osiris to receive his judgment; if the judgment was negative, the heart was given up to the goddess Ammit for destruction after the Amarna period , and the deceased was threatened with staying in darkness . It was not “innocence” that determined the judgment, but the ability to detach oneself from one's sins .

Beyond beliefs: If you passed the judgment of the dead, you could travel on through the underworld Ta-djeser to the bright place Sechet-iaru . Here the continuation of this life awaited you, with the ushabti doing the work for you. In the realm of the dead, in which one depending on grave goods more or less secure and comfortable living, there was next to the Duat or Nenets ( Against Sky ) the extermination site . There those eaten suffered their punishments and underworld snakes in their pits inflicted their ultimate death. In Christianity, this process corresponds to the practiced conception of hell , which may have penetrated into Christianity from here. Because at least in pre-exilic Judaism there is no such place of punishment, but only a desolate underworld ( Sheol ). Only in the Hellenistic epoch was it supplemented by a penal place Gehenna ; similar in Mesopotamia. The grave was her place of residence as the “ house of eternity ” with a false door to the west as access to the underworld. “Going out during the day”, that is to say, to travel across the sky with the sun god Re on the sun barge and to survive the dangerous night voyage threatened by Apophis , was the reward of the Ba souls or ancestral spirits lingering in the underworld. The fate reserved for the pharaohs after their death was the ascent to the divine circumpolar stars. The judgment of the dead was of great importance to the Egyptians, as was the entire care for the afterlife, since the dead were dependent on food (sacrifice). The underworld, through which the sun barge also drove every night, was perceived as unsafe, a place where numerous dangers threatened, often in the form of animal demons.

Sociology of religion : The fact that the western realm of the dead was understood, on the one hand, as a place of horror and, on the other, paradoxically, quite positively, is due to the mixing of chthonic ideas of a fertility cult around Osiris with those of a sun cult determinedby the world god Re . Here old peasant and old nomadic concepts come together, as theyare thematizedin mythology through the fight between Osiris and Seth and which apparently reflect prehistoric population conflicts. These conflicts were related to the Aridization of the Sahara during the history of North Africa and at the beginning of the ancient Egyptian empire between 3500 and 2800 BC. Together. Possibly they were the trigger for the formation of the empire, since the population pressure evidently led to an increasing enslavement of the nomads pushing into the Nile valley. Overall, the Egyptian conceptions of the judgment of the dead and the afterlife are thus a heterogeneous mixture of different religious traditions, in the development of which a “blurring theology”, for example with antagonisms between Re and Osiris, is conspicuous and incompatible things have been combined. Overall, in the Egyptians' belief in the afterlife, magical ideas outweighed religious and moral ideas, and according to SA Tokarev the concept was "evidently developed by the priests in the interests of the ruling class as a reaction to growing class antagonisms". The Marxist ethnologist and religious scholar wrote further: “The slave owners and priests were anxious to intimidate the superstitious mass of the enslaved people by threatening punishments in the hereafter and to comfort them with the hope of reward in the hereafter. For the era of the Middle Kingdom , especially for the period of severe social upheavals in the 18th century BC. Chr. ... this is very indicative. Certainly the Egyptian doctrine of the judgment of the dead later influenced the development of similar ideas in Christianity to a certain extent. ”With the exception of the deceased pharaohs in ancient Egypt, there was hardly any ancestor cult outside of the cult of the dead and burial.

Ancient oriental cultures

The ancient oriental conceptions of justice extend into the afterlife, as the Egyptian cult of Osiris shows with its concept of a judgment of the dead. This is where an individual “debt” is settled after death. This “guilt” is based on the non-compliance with this-world rules, which the respective rulers have enacted in the service of maintaining their power and which increase the pressure to comply with them with the threat of a penalty after death. The same principle applies to the other religions of salvation and the Mediterranean mystery cults . The ruler has a god-like position and is promoted by a caste of priests who did not make the current interpretation of the world available to the individual. The ancient custom, later also practiced in early African kingdoms, of electing a new king every year and ritually sacrificing the old one so as not to allow a constant rule, was soon circumvented by various measures. With the Hittites, for example, or in Mesopotamia, a “king for a day” or a substitute king was appointed for this occasion.

Mesopotamia

While the concepts of the judgment of the dead and the afterlife of ancient Egypt are rather hopeful, even with the possibility of magically deceiving the gods, the relevant Mesopotamian concepts are more of a grim and hopeless counter-image. This also applies to the old Canaanite-Jewish ideas of Sheol rubbed off.

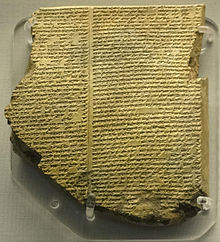

The main features of the concept of the afterlife in the religion of Mesopotamia were extremely pessimistic, the worship of the dead was shaped by the fear of the dead and the horror of their wretched fate in the underworld of Kurnugia , which was entered through seven terrible gates , a fate that met both good and bad. as far as these criteria occur at all. The fear of death and the search for immortality are described here for the first time in world literature ( Gilgamesh epic ). The basis was the idea that man was completely subordinate to the gods and was at their service. With the help of prescriptions and resolutions (the Me principles, which are similar to the ancient Ma'at concept of the Egyptians), the gods determined the fate of each individual and laid it down on divine fate tables. It was then the task of the people to carry out these resolutions in absolute submission. Life stretched linearly and came to an end with death, which released humans as a shadow existence into the underworld, which was ruled by the goddess Ereškigal , later together with Nergal . The rites of this world with their emphasis on the purification ceremonies for atonement were designed accordingly.

Actual judgment of the dead and the underworld: everyone who reached the kingdom of the dead via the Ḫubur underworld had to submit to a judgment of the dead. The process is described in fragments in the Epic of Gilgamesh (Flood Legend). Heroes like Gilgamesh appeared as pale judges of the dead, of which there were seven, mostly deceased and then like Gilgamesh deified great kings. In contrast to Egyptian ideas, there is hardly any reward or punishment in the afterlife, so there is no personal responsibility and no principle of retribution. Because fate was predetermined by the gods. Only fallen warriors were treated better, as were those who were well cared for by the living through sacrifices for the dead in their tombs ( kianag ). Fathers of several sons also had it better, as Enkidus' report from the realm of the dead shows. In general, however, the same dark fate lies over every dead person: he eats dirt, freezes, starves, thirsts and is feathered like a bird. If he is lucky, he can flee and in this world, according to the pronounced fear of demons of the Mesopotamians, frighten the living as an evil demon (so also in the ancient Arabic religions and from there in Islam, e.g. the jinn , but also in Christianity, for example in Halloween customs). Dead rituals and sacrifices were primarily intended to mitigate this fate of the dead, for example to provide them with at least pure water through libations.

The Sumerian royal tombs of Ur (around 2700 BC) discovered by Woolley show a very old and primeval layer of customs. They bear witness to massive human sacrifices, only found in Kiš , that were carried out during a burial. However, it is unclear whether it was believed that the dead ruler could take women, helpers and equipment with him to the afterlife. But similar examples can be found in other early cultures, which are taken as a sign of deification, which saved the king from the underworld. She got to even the pharaohs, but you had in Egypt after the first dynasty of the human sacrifice given up and is content in the grave with shabtis.

Parallels and references: Presumably the Israelites, insofar as they are not remnants of the patriarchal period (the biblical Abraham immigrated from Ur in southern Mesopotamia), adopted the Mesopotamian ideas for their own hell Gehenna (Gehinnom), especially during their exile. They roughly correspond to those of Hades , which also has a counterpart to Hell: the Tartarus . There are also parallels between the Gilgamesh epic, the Osiris myth and the Orpheus myth , which suggest that they are ancient oriental Mediterranean myths that continued to have an impact on ancient times. In Egypt there is also a (fertility) myth of the passage to hell of the goddess Inanni (in a different version of Ishtar ), who loses one of her divine abilities when passing through every gate. After the seventh gate she stands naked and disempowered in front of the underworld goddess Ereschkigal , whose death look she is at the mercy of and from which she can only escape through a foresighted trick.

Further development: Whether death is presented as something pleasant or gloomy has a massive impact on the present and the ethics of the living. Accordingly, this fear later led to a certain doubt about the meaning of it all. One did not want to submit to the inscrutable advice of the gods without further ado without being able to demand the slightest justice, so that now and then there was a very secular hedonism or a complete negation of the world. An ancestor cult as such existed, but mainly in the form of sacrifice and burial cults among the nobility and deified rulers. Otherwise one was more afraid of the spirits of the dead.

The Elamites , who lived east of the Tigris in what is now western Iran from 3000 BC. BC established an empire, had slightly different ideas. Their belief in the hereafter was structured strongly anthropomorphically ; many grave goods were found that suggest care for the afterlife. A pronounced fertility cult also seems to have played a role. The god of the dead Inšušinak (Sumer. Lord of Susa ) formed a supreme trinity together with the gods Humban and Chutran. The dead were received in an intermediate realm by the pair of gods Ishnikorat and Legamel, who acted as psychopomps , and brought them before the god of the dead, who judged them.

Old Iranian religion and Zoroastrianism

Although there are still remnants of it, especially in India (Parsism), Zoroastrianism is discussed among the historical religions. In comparison to the ancient Egyptian religion with its hopes of the afterlife determined by magical ideas and in comparison to the ideas of the afterlife of the Mesopotamians with their mercy and hopelessness, it represents a third basic type Dualism the main role.

As in other religions, especially if they have been alive for long periods of time, the concept of the hereafter varies greatly in the chronological order. In the earliest part of the Avesta , the Gathas , no physical resurrection is mentioned, although the idea of a judgment of the dead is already there. Only in the younger parts of the Avesta, which were built around 200 AD, is there talk of heaven and hell as physical places. This concept took shape even more when Judaism, Christianity, and Islam emerged and were influenced by Zoroastrianism.

Little is known about the ancient Iranian religion before Zarathustra because of numerous power-political and religious overlaps. However, since this originated from the old Iranian forms of religion, it is assumed that there must have been similarities to the religious concept he designed. Cultural and religious details or even a uniformity of culture and religion in the Iranian highlands of this period, in which also numerous different peoples crowded together, cannot be derived from the few finds. This only changes with Cyrus II in the Achaemenid period . At that time the belief in Ahura Mazda as the highest being was widespread, which Zarathustra took over as well as the old fire cult and developed it further into monotheism of a religion of revelation . The similarity to the Vedic religion is striking .

In Zoroastrianism (also Parsism and Mazdaism), which may have arisen about 3500 years ago, the good-bad dualism personified by Ahura Mazda and Ahriman is consistently developed for the first time in the history of religions and is at the center of ideas. A dualism of body and mind is strictly rejected, rather the evil arose through Ahriman's intervention that destroyed the original harmony. Accordingly, good and evil are primarily cosmic, non-ethical concepts, which only appear secondarily as signs of disturbed harmony in ethical phenomena. Accordingly, Zoroastrianism does not know an actual and cataclysmic end of the world, but a renewal of the original harmony. As a central element, this dualism also determines the ideas of the hereafter and of the judgment of the dead. Justice is absolutely human here, since Zoroastrianism for the first time grants people free will . Predestination, magic, protection, etc., on the other hand, are completely absent from Zarathustra's basic concept, but have been preserved to this day as remnants of older ideas.

Judgment of the dead and the afterlife: The Iranian concepts, as they are mainly described in the Gathas , are very similar to the Indo-Vedic of the Upanishads . Physical death is related to the forces of evil. Therefore, anyone who touches a corpse becomes defiled. Death therefore decays in the towers of silence . The bones were collected in order to await the last judgment in the grave, an old concept of the bone soul, as found in some North American Indians (see there) . Even the holy and pure fire was not allowed to come into contact with it. The soul is thought of as a spiritual principle and does not need the body. Heaven and Hell are places in the hereafter that are each assigned as a result of thoughts, words and deeds. There is thus an accountability of the person towards Ahura Mazda (also: Ohrmuzd), and thus a judgment of the dead is necessary. There, after death, individual punishments are assigned in a first judgment by means of a scale of justice, which correspond to the behavior in life. In this way moral principles of this world such as justice gain greater importance again, especially the main duty of the believer: the promotion of good creation, whereby the harmony concept that connects the spiritual and physical world plays an important role. When the good thoughts, deeds and words of man outnumber the bad, a beautiful virgin receives his soul at the bridge of selection (Činvat Bridge) and leads her to the other side (cf. Huris in Islam). Amescha Spenta , the good disposition, awaits him there and leads him to heaven. If the evil thoughts, deeds and words predominate, his soul encounters a witch as the personification of his conscience and falls from the now razor-sharp bridge into hell ruled by Angra Mainyu (= Ahriman). There is also an unspecified third place for souls where good and bad are in balance. The punishments in hell correspond to the severity of the offense, because the goal is to educate people. The greatest virtues of man are the careful cultivation of the soil, keeping contracts, righteousness, and doing good deeds; The most serious violations are those against ritual purity, which condemn man to eternal death: burning a corpse, eating a corpse, unnatural sexuality ( sodomy ).

In a later time the judgment took place on the other side of the bridge, first by a judge, later by a college of three chaired by Mithras . In addition to the way of life, it was important whether the dead had worshiped the right or the wrong gods.

After a certain point in time, the dead are sent back from heaven and hell to undergo a second judgment on the occasion of the resurrection of the world at the end of the Zoroastrian cosmic cycles of 12,000 years. The decisive factor is whether the person has lived in harmony with both aspects of being. Man has to face two judgments because there are two aspects of being: menok and geti , the spiritual and the material form of the world. The future resurrection of the flesh and the Last Judgment , followed by eternal life for body and soul, are correspondingly the final “restoration” of Ohrmuzd's “good creation”, the removal of evil from it and the union with him. An eternal hell is considered immoral, and thus all people will become immortal after having served their punishments in hell if they have undergone the second judgment on the occasion of the resurrection of the world. However, on this occasion the sinners are removed from the world together with Ahriman, that is, they are destroyed, so that, according to SA Tokarev, the ideas of the afterlife of Zoroastrianism are basically "permeated by the moral idea of retribution".

Sociology of religion: The origin of this strict dualism of the Avesta , which extends well beyond death , is now seen in the enmity between the settled peasants and the nomadic cattle herders of the Indoarians , which can be found in the story of Cain and Abel and in the battles between the Iranian Ahura - and the Indian Daeva worshipers. The careful cultivation of the soil as the main virtue points in this direction, as does the obligation to comply with contracts, etc., especially since the other virtues are relatively vague. Zoroastrianism did not take its final form until the beginning of the Achaemenid period from the sixth century BC after the power-political replacement of the Medes and became a centralized priestly cult , especially under the Sassanids . According to SA Tokarev, the development of Zoroastrianism reflects the development of the Iranian states with the escalation of class differences. There was an ancestral cult as a cult of the dead, mainly to appease the spirits of the dead who were believed to have power over the affairs of the living.

The later Gnosticism influenced by Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism exerted an influence on early Christianity. Later, the basic dualistic ideas in Christianity can be found mainly in the sects of the Paulikians (7th century), the Bogomils (10th century), the Cathars and Albigensians (12th / 13th centuries).

Ancient Near Eastern Religions

These are the religions practiced in Asia Minor and Palestine, i.e. in the Mediterranean East, which show some similarities. These are mainly dualistic fertility cults ( Ba'al versus Mot) and partly strongly syncretistic religions that contain Mesopotamian elements. Above all, Palestine was shaped by city-state cults, as due to the overlapping zones of influence of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran and Asia Minor, larger independent territorial states could only rarely and briefly form here.

Syria and Palestine

At least in the Early Stone Age there was apparently no actual cult of ancestors and deaths. There was probably a vegetative-polar idea in which the lower, earthly world corresponded to an upper, heavenly world and in which the earth was female, the sky was male and both primordial powers had created all living things together. At death the ashes of the earth were given back as their share, heaven received its own with soul or spirit. The cremation sites deep in the ground point in this direction. Any kind of afterlife with a judgment of the dead was thus superfluous.

Late Neolithic in Palestine-Syria there was a megalithic cult with menhirs (so-called mazebas ), which were especially dedicated to the dead. It was believed that the dead lived in them and occasionally sent revelation dreams when one slept there. The meaning is not clear. The ancient cult site of the god Moloch in the Hinnom valley south of Jerusalem became in Judaism Gehenna , hell as a place of punishment.

The Semitic peoples may have immigrated from the Arabian Peninsula, the Sinai or Mesopotamia and the Syrian desert in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. The ideas of the underworld are generally rather diffuse, occasionally determined by polar myths of the gods' warfare (Mot devours Baal). As in early and middle Judaism, there was apparently no judgment of the dead. Due to the vegetation-mythical structure of the other religions, this is not likely. The same applies to other Bronze Age Semitic tribes in the region: the Moabites , the Ammonites , who worshiped Moloch, the Edomites , Amorites , Nabataeans and other mostly originally nomadic peoples.

Hittites, Urartu

The religion of the Hittites , which has only been handed down as a state cult, primarily adopted myths from Anatolia , but also the ideas and myths of many neighboring peoples. There were extensive death rituals for the divine kings. But even the “simple” dead finally went to the other world. However, there was apparently no judgment of the dead, just as little in the cultures of the successor states.

The religion of Urartu ( Chaldeans ) is characterized by the gods' legal claims against humans. Almost nothing has been handed down about ideas about the hereafter. Nothing is known about a judgment of the dead. The same applies to the Phrygians , about whose religion little is known.

Ancient Classical Religions

In the ancient religions of the Mediterranean region, everyone had to seek and fill their place in life. Greeks, Etruscans and Romans - if at all - have rather weak ideas about the judgment of the dead . The focus was on observing the rites of the dead.

The funeral cult was strongly pronounced among Etruscans and Romans, especially among the ruling class. There are also strong remnants of a manic ancestral cult. However, since such an ancestral cult usually excludes or only contains reduced judgments of the dead, these are probably to be understood as adoptions from Hellenism.

Greeks

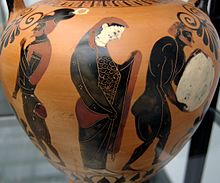

According to Hesiod and Pindar, as well as Homer and Plato (e.g. in Der Staat , Book 10), people initially believed in a kind of island of the blessed, Elysion , where, besides relatives of gods and heroes , the one who proves himself in three reincarnations on earth had, was allowed to go. Only a few such as Heracles , Perseus , Andromeda , Cassiopeia or the Dioscuri were transferred directly to Olympus or to the stars. The later ideas represent the old cosmological tripartite division: the Tartaros , a place of punishment where the fallen titans and other evildoers or former divine power competitors who had acted against the divine will suffer; to Hades , a milder anything but bleak underworld; the Elysion, a heavenly place.

The underworld called Hades is God and place in one. This is where the feeble dead shadows live, which you have to strengthen with food and libations so that they can speak at all. The dead are led from Hermes to the underworld river Styx , which they cross with the help of the ferryman Charon , who has to be paid with the so-called obolus . There they step through the underworld gate guarded by the hellhound Kerberos . So that they are not eaten by him, they are given honey cake .

The old religious ideas of Hades were replaced by philosophical ones in Plato , in which the concept of virtue ( Areté ) gained importance and gave people a self-determined means of overcoming such dark ideas. The Orphic turn, in the center of the doctrine was the fate of the dead, tried to secure a blissful afterlife the faithful through mystical ceremonies.

There is a clear judgment of the dead here . According to later tradition, the three judges of the dead, Minos , Rhadamanthys and Aiakos, cheerfully assist Hades, who is relentlessly strict as an underworld god , on the Asphodelos meadow . The souls of the righteous are directed into the blissful Elysion realms around which Lethe , “the river of oblivion”, flowed, the ancient island of the blessed. After a negative judgment, however, sinners had to go through long purification ceremonies before they achieved the status of blessed and, after they had also drunk from the Lethe River, were allowed to go to Elysion. Before that, however, they were allowed to choose their future incarnation themselves. The most serious sinners were damned forever.

There is also the idea of punishing wicked people who have aroused the wrath of the gods. They are thrown into the abyss of Tartarus , the terrible place of exile, where they have to atone for their misdeeds in various ways ( Sisyphus , Tantalus , the Danaids , Prometheus , Minos , etc.). Except for the few deified, no one is spared Hades.

It was widely believed that the fate of the dead depended on whether the living performed the required ceremonies on the corpse. Therefore, these took a central position in the Greek religion. Accordingly, the souls of the unburied found no rest. Sacrifices for the feeding of souls were considered very important.

Etruscan

The structure of the Etruscan religion, which is characterized by a pronounced cult of the dead, is archaic and extremely complex. It is not known whether there was an actual judgment of the dead. There was also a "Charun" clearly modeled after the Greek underworld ship Charon, but this is also only attested from the 4th century BC. It was then that the pairing Persephone / Hades (Phersipnai / Eita) appeared, apparently under Greek influence. A deification of the dead was possible; it could be achieved through sacrifice. Judging by the paintings and sculptures in the necropolis, one believed in a joyful after-existence.

Romans

Little is known about the early Roman conceptions of the afterlife ; all in all, they remained rather vague later on. The fate fate was like largely mapped out by the Etruscans. The ancestor cult was pronounced. It was believed that the soul would continue to live in a paradise and that there was a kind of reciprocal relationship of trust between gods and humans. Later the Romans largely adopted the religious ideas of the Greeks. They mixed them with Etruscan and ancient Italian concepts to create a politically effective state cult. A strong longing for salvation is unmistakable in the imperial era , which gripped people in the spiritual and political turmoil and which, among other things, prepared the ground for Christianity. With this, completely different, far more precise concepts of the afterlife and the judgment of the dead were introduced, for example Greek, Egyptian, Persian and Christian-Jewish ones. In Virgil's sixth song of the Aeneid (29–19 BC) the adoption of Greek ideas about the hereafter is particularly clearly attested. A separate Roman judgment for the dead, apart from Greek concepts, did not exist in the strongly worldly oriented Roman culture. Regardless of this, observance of the rituals of the dead was very important in order to save the dead from a possibly bad fate.

Old European religions

The Celts, Teutons and Slavs and especially those of the Balts, Finno-Ugric peoples, Scythians, Thracians and Illyrians are difficult to reconstruct because the sources are poor overall. There are two main reasons for this:

- These peoples were not homogeneous societies , but rather loosely divided into tribes and local rulers, which sometimes never formed states at all, sometimes only very late, and which also lived scattered across large parts of Europe.

- The influence of Christianity made itself felt early on. Much of what is now considered "Germanic" is already influenced by Christianity. But ancient Greek ideas and the structure of the underworld along with individual motifs, such as the bridge to the underworld, hell river Gjoll , the hellhound Garmr or the bridge guarding giant Modgud seem to have quite early acting on their afterlife. Other researchers value them as remnants of an all-Indo-European tradition.

Celts

The religion of the Celts is probably rooted in the still very egalitarian urn field culture . We do not find a pronounced good-bad dualism and accordingly neither gods-fighting myths nor a judgment of the dead. Possibly there was a vegetative dualism (see above) . Nowhere in Celtic eschatology is there any mention of guilt, punishment and judgment in the afterlife. Instead, there was a pronounced belief in the migration of souls and an interaction between this world and a pleasantly conceived afterlife without death, work and winter.

Scythians

Little is known about the religious ideas of the Scythians . There seems to have been no judgment of the dead.

Germanic peoples

In the religion of the Germanic peoples , which because of the large area of distribution is by no means uniform and, as far as dying and afterlife are concerned, rather dark, the whereabouts of the dead was the lightless Hel . Originally it was not considered a place of the damned, who had to serve a sentence there at “places of agony like the Nystrand ” (the beach of the dead) (already a Christian idea that had a strong impact on the Völuspá here). Accordingly, there is no judgment of the dead. Some tribes did not believe in an afterlife at all; life was irrevocably over with death. Every misfortune was better than death, because at least one lived (according to Hávamál ). More often, however, it was believed that life would go on as before after death, and that one could be killed two or three times in the same body before it was finally over. It remains unclear whether this required a journey through the dead. In the north, the local Hel was developed as the underworld goddess. The place Hel became a punishment place of hell under Christian influence. The moral quality of the dead (here initially his merits as a warrior) increasingly became the reason for the assignment, whereby initially only the positive selection of the Valkyries on the battlefield was decisive. The underlying idea comes from the Migration Period (4th century AD) and was not handed down in writing in the Snorra Edda until the 9th century AD . Perhaps Christian motifs were already incorporated, because, according to Wolfgang Golther : "In reality, Hel and Walhalla are one, the great, all-embracing realm of souls."

At first there was mostly only Hel for the dead of the pre-Christian Teutons, in which life was by no means miserable. Rather, it was very similar to earthly. A festive reception was prepared for the noble. Only in some North Germanic tribes is Walhalla even present as the last refuge of a specialized warrior caste. Even the Dane Saxo Grammaticus only speaks of underground places of death - those for warriors with pleasant green areas and for "envious people" in snake-deep caves in the north.

Slavs

The old Slavic belief, which we only know in outline, was shaped by the belief in nature spirits (→ animism ) and the perceived kinship with animals. Partly elaborate grave goods indicate pronounced ideas of the afterlife. There seems to have been a kind of paradise and a fiery place where the wicked suffered. With the Eastern Slavs , the type of death was also decisive: was it natural or unnatural? An ancestor cult seems to have been widespread. There was the idea of a peaceful life after death and apparently no judgment of the dead. The soul left the body after death, either stayed there or went into an afterlife.

Baltic and Finno-Ugric religion

Both religions have no judgment of the dead. The Baltic mythology knows a positive fate expectancy. The dead easily crosses the border to the hereafter, where they expect no punishment.

Thracians and Illyrians

According to Herodotus , the Thracians and Illyrians had a real longing for death, believed in the immortality of the soul and had very positive ideas about the afterlife. Any court proceedings for the dead are unlikely.

Religions of Central America and the Andes

The religions of the pre-Columbian regions not only of the formative (1500 BC-100 AD), but also of the classical (100 BC-900 AD) and post-classical periods (900-1519) are strong shaped by the animistic belief in ghosts. There were significant temporal (e.g. Olmec , Zapotec , Toltec , Mixtec , Chavin , Nazca , Paracas , Mochica , Chimu , etc.), regional and local differences (e.g. La Venta , Teotihuacan , Monte Alban , Tikal , Palenque , Copán , Chichen Itza , Tenochtitlan , Tiahuanaco ) in cult and gods. Certain principles and myths were common to all. The problem of tradition also arises here sharply.

Central America

The Maya religion was ruled by submission to the will of the gods and the laws of the universe. There was a strong belief in predestination and a strong awareness of sin as an offense against laws determined by the priests on the basis of astronomical and oracle techniques. Numerous sacrifices were made, especially human sacrifices. In contrast to the central Mexican religions, there is no paradise among the Mayans. Cyclical eschatological concepts based on a complex calendar were already pronounced. The Mayans paid special attention to the royal dead because they were considered divine.

The Aztec religion was arguably the most highly developed part of their culture and was extremely complex. The universe was viewed as unstable and had to be stabilized through constant sacrifices. Fate was completely subject to the almighty laws of the calendar .

With the Aztecs there is no real judicial or ethical judgment of the dead aimed at weighing merits and offenses , at most one derived from external approaches. It was the human task to fight and die for gods and world order. Magic, oracles, and signs dominated everyday life; the worldview was very pessimistic. In addition, there was generally an ancestral cult that was also fertility cult. The Central American gods are mostly vegetation deities for rain, maize, etc. The Aztecs conception of the afterlife does not depend on the earthly lifestyle of a person, but on the type of death and the earlier professional social position of the dead soul, the potency of which it takes into the realm of the dead. A close relationship to the blood of the sacrifice, in turn a connection to fertility, is characteristic of all pre-Columbian cultures; likewise a sacrificial cult with human sacrifice.

Cosmologically , the world was divided into three parts: the upper world, the solid world, the water world and the underworld. These main worlds were partly subdivided into up to 13 overworlds and 9 to 13 underworlds, the latter as sometimes dangerous abodes of the souls. The whole thing is overlaid by a cyclical cosmogonic "principle of four" (four world ages, four quadrants of the four cardinal points, etc.).

This underworld was ruled by the twelve dark lords with names such as "One Death", "Bringer of Pus", "Bone Staff" or "Blood is its Claw", ie de facto by demons. According to the Mayans and Aztecs, whoever died had to descend to a place of fear ( Xibalbá ) and, led by a death dog (very similar to the Cerberos of the Greeks), take the dangerous path down, crossing a seven-armed underworld river. He was then tested and humiliated by the lords of the underworld until they released the soul again. It seems that there has been a kind of general judgment of the dead, but less as a kind of reviewing authority, but more as a distribution function. Because apparently demonic arbitrariness and the inexplicable will of the gods prevailed. Also, the subsequent procedure is not entirely clear, if there was one at all.

There were four paradises in the realm of the dead , corresponding to the four cardinal points: The warriors killed in battle went directly to the eastern paradise, the "sun house" Tonatiuhichan , where they met the people who had died as a sacrifice. There was also a western paradise, the “corn house” Cincalco , for those who died in cots, who were also worshiped, but who then occasionally appeared at crossings at night and paralyzed those who met them there. The dead, whose death was associated with the rain god Tlaloc , came to the southern paradise, which is described as extremely fertile , i.e. drowned people, those struck by lightning, but also those who had died of leprosy or other diseases. However , there was no direct route to the northern realm of the dead, Mictlan . To reach Mictlan, tests of courage had to be passed in nine different locations before being admitted there after four years. There was also a god of the dead, Mictlantecuhtli , who ruled the northern realm of the dead together with his wife Mictecacíhuatl . Once the dead man got there, he simply disappeared.

The creator couple Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl lived in the uppermost of the 13 (or 9) afterlife. The small children who died were the only human dead to arrive here.

Andean religions

In South America, especially in the precursor cultures of the Incas, mummy cults can be detected in necropolises, which point to the belief in a body-bound survival after death. Since there are no written documents here, only archaeological finds, we can only make assumptions about whether there were ideas about a court of death at that time. This seems rather questionable.

For the Inca ruler it was assumed that he would occupy the same godlike position in the hereafter as in this world; for the nobility, who developed a rich funeral cult, corresponding gradations were valid. For the Incas, however, in contrast to the Central American cultures, a judgment of the dead is not even rudimentary.

Living religions

Judaism, Christianity, Islam

In the monotheistic revelation religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the judgment of the dead is closely connected with the end of the world ( apocalypse ), the resurrection from the dead, the final judgment and the final redemption . The sometimes highly differentiated conceptions of the hereafter are often contradictory, blurred or, as in Christianity, especially in its doctrine of grace and justification , or in the doctrine of predestination of Islam, are transferred to the divine and therefore inexplicable will. Secondly, human ideas of justice are subordinated to this will, as can be seen in Dante's “Divine Comedy” with its highly scholastic systematizations of sin and differentiation of punishments. This was particularly useful for maintaining the power of church and state or the caliphate .

From ancient, mostly Greek traditions, thoughts of transmigration of souls have penetrated here and there into Christianity and Judaism . In Kabbalistic Hasidism , the notion of the transmigration of Gilgul's souls, developed especially in the Book of Zohar , has gained a foothold since the late Middle Ages. The Zoroastrianism has essentially acted with his strict dualism of good and evil and his judgment of the dead ideas of the monotheistic religions of revelation, about the Manichaeism and the derived from it groupings.

Of particular importance is the extent to which the establishment of the court of death institutionalized in the monotheistic religions is influenced by the central notion of violence and the exclusive concept of truth, as described by Jan Assmann . This is accompanied by the extraordinary importance of sin and the exclusive bond with the one God, which produces a pronounced repentance when his laws are broken and requires a mechanism for their dissolution.

Judaism

The Judaism reflected in its development stages, many of the ideas that occur in later sister religions to death, afterlife and eschatology, which is why it is considered in more detail. His ideas are extremely heterogeneous and can only be represented in a historical longitudinal section. Because in Palestine different historical and religious developments overlap. In addition, the Jewish tribes each brought their own traditions about life after death. The officially forbidden necromancy was widespread (see Saul's visit to the witch of Endor ). Basically, there are five development phases:

Nomadic period and pre-exile period (First Reich up to approx. 539 BC): Little is known about the earliest period of nomadism and their ideas about the hereafter. There was no retaliation after death. God punished people either in this world or in their descendants. During this period, the belief in gods protecting the kin ( teraphim ) and possibly ancestral spirits was widespread . The eschatology of this period is unique in that it deals with the collective fate of the nation, but shows little interest in the fate of the individual after death (cf. Ecclesiastes [Kohelet] 9, 5).

Judaism's primary conceptions of the afterlife are extremely pessimistic in Israel's archaic period before exile. Originally, death did not belong to creation, but was a consequence of the Fall; In addition, the depictions of Genesis 1–11 on the origin of evil are very inconsistent. There was also no conception of body and soul and a corresponding dualism , rather life was seen as a unit, and blood was considered the soul or at least its carrier. In early Judaism, it was initially assumed that there is no further life after death and thus no immortality (except indirectly through offspring). Accordingly, one wished for a long earthly life in order to postpone this fate as long as possible. The realm of the dead Sheol , into which all the dead came without distinction, had no connection with God, but was subject to his suzerainty. It was presented as underground, cold and dark and apparently follows Mesopotamian models. All differences, including good and bad, stopped there; there was no thinking, feeling and no wisdom. There was therefore no unnecessary judgment of the dead. Very few people whom God consumed directly escaped it. Concepts of eternity always referred to the entire chosen people of Israel. The strictness of the old Jewish, pre-exilic concept of death has paradoxically led to the development of countless rites of the living around death. They all had the purpose of preserving the memory of the deceased with the living for as long as possible, since it was only in a certain sense that it lived on. In addition, the dead body was handled extremely carefully, as it was God's property and therefore must not be destroyed and later, when a resurrection was thought to be conceivable, it must be available intact. However, this implies the question of why God did not guarantee this on his own and needed the help of people. When the idea of a soul came up is unclear, especially since there were two words for it: nefesch and ruach .

Babylonian exile (597–538 BC) and post-exile period (Second Empire 538 BC to 70 AD): In the post- exile period, the first differentiation of the realm of the dead came about. One beganto differentiatethe Sheol from the Gehenna , which was now presented as a place of punishment. The distinction corresponded to that between the Greek Hades and Tartaros, which probablypenetrated Judaismthrough Hellenism (4th century before to 2nd century after Christ). Gehenna is the Greek form of the Hebrew Gehinnom.

The cosmology of the Jews, which was also strongly influenced by Mesopotamian ideas and later enriched by Zoroastrianism , apparently prevented a clear expression of ideas about the afterlife. According to SA Tokarev, the pre-exilic idea of the "chosenness of the people of Israel", which was particularly conspicuous in post-exile during the Second Temple period , increasingly replaced the idea of retribution after death. Because after the intensification of class antagonisms, it became necessary to give the oppressed people a kind of religious consolation, which in most religions compensates for the suffering in this world as retribution after death and as a reward in the hereafter. This made a judgment of the dead necessary, which was individually superfluous because of the purely collective idea of being elected, especially since the divine punishments always hit the people in this world. The reforms of the kings Hezekiah and especially Josiah were already aimed in this direction.

The religious-philosophical ideas of Hellenism left hardly any traces in Judaism during this period. His abstract metaphysical concepts did not or hardly penetrated or only much later in the first phase of the diaspora . Concepts of the afterlife, ideas of the immortality of the soul, of retribution after death, etc. are completely absent. God rewards and punishes the people here on earth, if not directly, then at least their descendants. Already in the final phase of state Judaism in the first two centuries before Christianity, the doctrine of the resurrection of the body won first with Isaiah (26:19), later with Daniel (168 BC), partly with Daniel with the idea of reward or punishment , more and more followers. At first it was aimed at those who fell in battle. Like the idea of a necessary judgment for the dead, it was strictly rejected by the Sadducees, for whom death meant the absolute end (Paulus, Acts 23, 8). However, Sheol received several “divisions”, depending on the sinfulness of the inmates.

At the turn of the century, the three competing theological currents of Judaism, Sadducees , Pharisees and Essenes , of which ultimately only the Pharisees survived in rabbinism , are important in this context . According to the most important Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37/38 to approx. 100 AD), whose traditions here could be incomplete or even distorted, the Sadducees believed that man had free will , the Essenes believed in a predestination of man , while the Pharisees taught free will with a foreknowledge of God (similar to the Asharites in Islam). The Pharisees also differed from the Sadducees, who appointed the Jerusalem temple priests, in that they believed in a resurrection of the dead who would be judged underground. The righteous pass into other bodies (by which no transmigration of souls should be meant, since it was probably not a matter of material bodies), while the wicked are forever punished and kept in captivity. According to the Mishnah , eternal life is only lost if someone denies the resurrection of the dead, the divine origin of the Torah , the most important religious foundation of Judaism to this day, or the divine destiny of human fate. The Pharisees' achievement was to overcome the temple alignment of Judaism by sanctifying everyday life by observing Jewish regulations. Jesus ' teaching was close to both the Essenes and the Pharisees. All in all, Hellenism with Orphic and Platonic ideas had an increasing influence on Judaism and its ideas about death from the 1st century BC.

Talmudic period and rabbinism (up to approx. 700 AD): After the destruction of the temple in 70 AD and the beginning of the diaspora , the rabbinical doctrine of the Messiah gainedmore and more supporters, and Hellenistic ideas settled due to the coexistence with these peoples, finally through. Associated with this was the belief in a bodily resurrection of the body within the framework of an eschatology, which has since been reflected in strict funeral regulations such as the prohibition of cremation, autopsy and mummification, etc., which partially destroys the body. Judaism changed from a pure, ethnically and this-sidedly determined revelation religion withthe goal of the “promised land” to a redemption religion with an otherworldly focus on resurrection and eternal life. This gave rise to the theoretical necessity of conceiving a quasi pre-selecting intermediate instance, which distributed the people accordingly in hell ( Gehenna ) and the Sheol waiting area for the paradise Gan Eden , the rather vaguely imagined place of the righteous after death and a last judgment which now remained just as necessary. The criminal court, it was believed, would last twelve months in Gehenna (if the Sabbath is observed there as well, since no fires are allowed to burn on that day) and be based on the righteousness of people, including that of non-Jews. The old idea, promoted by class contradictions, of acquiring eternal bliss in the hereafter through good works in this world (and the study of the Torah) gained importance in the Talmud.

Medieval Judaism (700 to approx. 1750 AD): In the rabbinical Judaism of the diaspora , a serious theological change had begun, and the resurrection (to this day mainly in the eighteen supplications , the Schemone Esre present) including the Last Judgment and eternal life in Paradise was now accepted as such through the inclusion of Christian ideas. This process was completed by the 9th century, whereby Orthodoxy is based on the physical resurrection, whereas modern Judaism understands the resurrection as a spiritual and spiritual process of redemption. The 13 beliefs of Maimonides explicitly mention notions of reward and punishment for the just and the unjust. Accordingly, the coming world is the reward of the righteous, while the unrighteous are punished with the destruction of their souls. Above all, the mystically oriented Kabbalah was dedicated to the problem of rebirth and the judgment of the dead. She designed a highly complex structure of the human soul, whereby only the lowest level nefesh , the animal soul, had to endure divine punishments, the spiritual soul ruach, however, was admitted into paradise and the immaculate soul neschamah entered God. Ideas of a transmigration of souls Gilgul developed and the physical resurrection was viewed as inferior to true eternal life.

Modern Judaism from 1750: The Messianism and resurrection of thought are now a central idea especially of Orthodox Judaism. The Reformed Judaism of Haskala , which adhered to rational ideas , rejected both and avoided all discussions about life after death, especially in the 20th century. Both concepts were urgently needed as immovable hope during the almost two thousand years of the diaspora, because they, like strict adherence to traditional principles and rites, held the people together, with complex catalogs of regulations such as in the Shulchan Aruch , which, among other things, also contained the kashrut - Contains dietary laws. However, this behavior has contributed not a little to the isolation and ghettoization of the Jews in other societies and thus to anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism with its repeatedly flaring pogroms , especially in Poland and Russia. But the focus in Judaism is still on this world, since only here can humans receive and do what is good. Since then, the main interest of Judaism has been directed towards the return of the Messiah and what would happen with it, hopes in which ecstatic catastrophe fantasies are controversially bundled with ideas of salvation from the building of the third temple and more realistic historical-political ideas ( Zionism , Greater Israel , settler movement) and give the State of Israel a significant part of its internal and external tensions.

The modern Jewish theology has also influenced by the rationalist philosophy of Baruch Spinoza's discussion of a practical design of the afterlife and judgment of the dead largely removed, especially with the artifice of death now than sleeping on a purely spiritual place (so later, under the influential Aristotelian thought good standing Maimonides ) to display a waking up in the judgment from which the wicked, so especially the non-Jews (and formerly the slaves), are excluded (and the Christ then redeemed by his death, including descent into hell, mainly in the The lower class of the Roman Empire and among the slaves contributed significantly to its great success). This resulted in two contrary theological currents, incompatible also in the eschatological and the afterlife, which still determine Judaism (and the State of Israel) today:

- the rationalism of Maimonides and Moses Mendelssohn , which ultimately led to the Haskala , the Jewish Enlightenment, and which also brought about the Zionism of Theodor Herzl ,

- the opposite of the mysticism of Kabbalah , especially of the Book of Zohar , which led to Eastern European Hasidism and ultra- orthodoxy , which ultimately led to the national religious parties or the settler movement such as the Gush Emunim .

The Shoah exerted another profound influence on these concepts . How much this influenced criminal and court ideas still determine Orthodox Judaism today is shown, for example, by a statement made by the high-ranking ultra-conservative rabbi Ovadja Josef from the year 2000, which was later formally withdrawn under public pressure : “The six million Jews who were cursed by the hands Nazis murdered were resuscitated souls of sinners who had sinned and led others to sin, as well as doing all sorts of prohibited things (for Jews). Their poor souls came back to be cleansed of their sins through all the terrible tortures and through their deaths. "

Christianity

Basics: Christian conceptions of the judgment of the dead are diverse. They are based on Jewish, Greco-Hellenistic, Oriental and Medieval traditions. They also repeatedly reflect political situations. The rulers influenced the belief in the hereafter and the ideas of the judgment of the dead (very nice with Dante, who banished the unpopular popes and princes to hell ) and used them economically. Examples are the crusades and the indulgence trade . With the persecution of heretics and the burning of witches , with the ban from church and excommunication , the judgment of the dead was de facto transferred to this world. The burnings were justified by the fact that those affected escaped eternal damnation because the soul would be purified by the fire. The ban meant exclusion from divine grace mediated only by the church.

The fact is that, despite all the legends about demons, angels of death, spirits, stray souls, etc., such a preliminary judgment does not exist in New Testament Christianity as a closed and coherent construct and the question of the nature and structure of the afterlife before the Apocalypse without a more precise one Answer remains. The reason is simple: already Christ and especially his first followers believed in an apocalypse predicted by him in the near future and still during the lifetime of the evangelists ( parousia ). Further constructs about death and the underworld were therefore simply not necessary at first, a gap that was then felt more and more painful over time, into which later, slightly pagan and often very different regionally popular ideas of sometimes extremely brutal afterlife customs, as described by Dante, penetrate and they could fill alternatively. Later ideas of Gnostics and other philosophical and theological currents such as Manichaeism were added ( Augustine, for example, was a Manichaean for some time).

General aspects of the Christian belief in the hereafter and the judgment of the dead , as formulated above all by the apostle Paul and the church fathers :

- The ethical claims of God, such as humility, charity, forgiving enemies, turning left / right cheek, etc., which, as it were, because no one can adhere to them, automatically create sinfulness, are almost impossible to fulfill in practice, partly stoic thinking. They are much stricter, even more radical, than in Judaism, the rest of which Christianity inherits, however, including the ideas about Gehenna (hell), resurrection and the Messiah, as they were theologically discussed at the time of Jesus.

- What is new is the idea of man's sinfulness and his redemption through divine grace , the central thought figures of Christianity in general, which then also form the ethical foundation of the judgment of the dead, although redemption is only guaranteed through unconditional submission to the church.

- The dualistic doctrine of Gnosis with the central idea of the Logos entered Christianity and the Logos merged with the figure of the Savior Jesus. This established a good-bad dualism that could only be resolved in the figure of Jesus, a prerequisite for his later function as world judge, which did not exist in Judaism. The doctrine of the Trinity , medieval Mariology and the veneration of saints then provided further components of an end-time world judgment that could act as advocates or defenders. At the same time, evil was personified as Satan , a role that did not exist in Judaism either and which already took up iconographic Greek influences ( Pan , who, like the satyrs , can be traced back to the early Neolithic goat demon).

- Another focus is the belief in the existence of an afterlife and in the resurrection as well as in the existence of an immortal soul, whose identity in the intermediate realm remains unclear. This results in a separation of soul and body, as it was already postulated in the patristic , whereby there were theological controversies about the details of the doctrine of the soul, especially in the Middle Ages, and the soul was divided into more and more components. However, up to Descartes there was at least one agreement that according to the ancient Greek conception the soul was responsible for the formation of will, consciousness and reason as well as for the physiological functions including the sensory impressions. Later, in Western philosophy and, most recently, in psychology, the mind-body problem , which is still discussed today, developed.

- The fate of the dead was originally based on the classic three-tier cosmology Heaven / Earth / Hell, as described by Dante and John Milton and how it is conceptually based on Goethe's Faust , even up to our century of Christian theology, above all, as for hell .

- Death is the result of sin, which came into the world through Adam and Eve (cf. original sin ) and which every human being now carries within himself as a merciless idea, mainly represented by Augustine, which is therefore not in East Rome as in West Rome personalized, but remains embedded in cosmological and healing-theoretical connections between death and resurrection.

- The church represents an intermediate worldly realm until the return of Jesus with the resurrection of the dead, who then no longer have an earthly body, but a spiritual one ( soma pneumatikon ).

- Everyone will be resurrected, but only those who trust Jesus ( justification by faith ) are redeemed . This will be decided at the Last Judgment . Like the doctrine of the chosen people of Israel, this leaves the fundamental question of God's righteousness towards all his creatures open.

- The grace and love of God as the mechanism of the eschatological judgment of the dead are disputed to this day in their extension to all, only Christian, only believing or even only specially chosen people.

Accordingly, there were several partly contradicting development phases and core ideas, which were characterized by sect formation, especially in the first centuries :

- After the near expectation of the parousia had not come true, people increasingly turned to the, albeit always very controversial, intermediate state between death and resurrection. At the same time, pre-Christian ideas spread again, according to which each individual would be judged in death in order to then be with God or else cut off from him completely. This interpretation was a consequence of the New Testament prophecies of a collective mass resurrection with a subsequent mass tribunal.

- With the idea of the intermediate realm of the dead, in addition to the idea of an immediate entry into paradise after death, which avoided this intermediate realm, but also the idea of two dishes, the personal after death and the eschatological at the end of time.

- Another concept postulated the sleep of the dead until the Last Judgment. But this seemed unfair, since here the punishment of sinners and the reward of the good would be delayed, and church fathers like Tertullian therefore later designed auxiliary constructions adopted by the Byzantine church of East Rome, which at least gave the souls of the righteous a kind of refreshment during this period.

- The conception of evil - and it is a prerequisite for an ethical judgment of the dead - remained very inconsistent in Christianity, especially in its interaction with culture and religion, could never really be solved in terms of its inherent problems and soon ended up either in the religious mysticism of popular belief or in philosophical theodicy . After the catastrophes of the 20th century, and especially the Shoah, the problem arose again in full sharpness.

- Diffuse chiliastic notions of the second coming of Christ in a thousand year earthly kingdom (Rev. 20: 1-6) before the actual end of the world with an “anticipatory resurrection” of the believers before the Last Judgment, a Christian re-molding of old Jewish Messiah concepts , added further to the confusion, especially since even then it was already judged and cleansed, but in the end Satan temporarily gained the upper hand again.

- All these very incoherent belief concepts , which also assumed that there was no possibility of reorientation after death, ultimately led in Catholicism to the development of an idea of limbo and above all of purgatory or purgatory (Latin: purification), in which this purification of minor sins (with Dante the seven deadly sins ) was still possible, but this could be shortened by the intercession of the church ( indulgence such as with Johann Tetzel : “As soon as the money rings in the box, the soul jumps out of the fire.”). The now set but again assume that the verdict damnation or salvation was final already at death, which is why Protestantism rejected this doctrine strictly and by the already by Augustine , starting with Paul (Rom., 3:28) conceived doctrine of justification replaced in which ultimately an individual judgment of the dead became unnecessary and the collective through divine grace, which was only granted to the believer, reduced to this one point, that of the endeavored faith.

So one could argue philosophically that there is a judgment of the dead in Christianity with the necessary ideas, iconographies, instances and procedures, although conceptual and vague - but these are not really Christian in the narrower, not defined in terms of power politics or religious history, etc. modern acceptable sense.

Particularly noteworthy is the medieval iconography of the court , which is mainly on the account of their high grade and extremely esoteric Bildsymbolismus often misunderstood and only after 367 n. Chr. Canonized by Martin Luther and John Calvin as unpaulinisch rejected Apocalypse of John (chap. 21 ) as well as based on the Jewish Garden of Eden , Heavenly Jerusalem and ancient models, as well as other pagan ones, e.g. B. took up Celtic, Slavic and Germanic ideas or had retroactive effects on them (cf. in particular "Germanic"). Great value was placed on deterrence, on the other hand the hope of the heavenly Jerusalem among the believers was nourished by particularly splendid representations, probably also in order to distract from the hopelessness of earthly existence, which mostly dominated the life of the people of that time with its social grievances by promising salvation and, above all, justice in the hereafter. Popular belief has in part preserved these figurative ideas to this day, although modern theology has long considered these concepts of the Last Judgment with a judge Jesus enthroned above the crowd of angelic choirs as mythological. However, some communities still hold on to such eschatological court presentations and have in some cases further differentiated them and provided them with elitist complexes of being chosen.

Islam

Basics: Islam's ideas about the judgment of the dead, eschatology and the afterlife are quite clearly outlined. However, the Koran does not offer a uniform or even systematic picture. Only the so-called "traditions" ( Hadith or Sunna ) and later theological treatises made the ideas more precise. Islam took over ancient Egyptian ideas (weighing of the soul) and adapted itself to the Christian idea of intercession and redemption. In addition, regional concepts of conquered peoples were incorporated.

Basics:

- Pre-Islamic in Arabia, death was an area into which one passed into an imperishable but inanimate cosmic space, completely separated from the living world, over which other gods ruled. Funeral customs were very important to keep the deceased safe. A murder had to be avenged in the sense of tribal honor so that the dead could rest.

- With these customs, Islam completely broke . Everything is now under the sole rule of Allah , to whom absolute loyalty and submission are due. Allah determines the length of life. Personal merit doesn't count. The only thing that matters is that man lived his life in the service of God. Correspondingly, he will also be judged on the Last Day (2nd Sura, 3–8). Elaborate funeral customs developed so that the dead would be ready on the day of resurrection. A cult of the dead was forbidden in the traditions, but this too gradually developed under the influence of old local traditions.

- The ethics of Islam are simple and far easier to fulfill than the Christian ethics . It is prescribed to be righteous, to reward good with good and evil with evil, to be generous, to help the poor, etc., as well as the formal commandments of the Five Pillars of Islam . Ethics is based on the assumption that creation is good and that man has to pass a test in it. The Koranic law serves as a guideline. The focus is on the principle of justice and encompasses all areas of human life. It leads to the application of the Talion principle . The focus is always on the community of believers, the ummah .

- Another central basis is the predestination doctrine of Islam, which is directly related to the good-bad problem , which was soon discussed controversially within Islam and led theologically to several splits and whose interpretations naturally have significant effects on the content of the judgment of the dead:

- Jabrians deny any free will. They are a radical breakaway from the Asharites, with whom they agree on most points.

- Qadrians grant humans a completely free will and are very similar to the Mutazilites , according to whose belief the moral law is not determined by divine revelation, but necessarily results from the order of nature or being. An act is already good or bad in itself, and even God cannot convert an evil act into a good one and vice versa.

- Asharites occupy a middle position and approve of a limited free will within the framework of the eternal divine will. They believe that evil is what God forbids through revelation, while good is that which he does not.

- A third key message of Islam is the eschatological doctrine of the Last Judgment and the afterlife.

Judgments for the dead: In Islam there is not just one judgment after death, but as in Christianity there are two, which, however, are much more clearly differentiated from each other and also better defined with regard to the time in between. Basically, if you include this interim period, you can speak of three dishes. There are also several variants of the sequence described below in the Islamic Book of the Dead :

- Intermediate course: Izra'il, the angel of death, has a special meaning (this idea also exists in medieval Christianity as a takeover from other religions, where there is usually such a companion, which on the other hand is not mentioned anywhere in the Bible). The task of the angel of death is to separate the soul rest from the body immediately after death (gently with Muslims, coarse with non-Muslims and "unclean" souls) and with the help of two white-faced angels to lead it to heaven, where it is received, if justified the highest spheres, is brought before Allah, but then returns again to her body on earth, where it sleeps until the resurrection. But if she belongs to the damned, i.e. the non-Muslims and bad faithful (only this criterion applies!), After the soul has been roughly separated from the body, she is carried to heaven by two black-faced, green-eyed angels, but rejected at the lowest gate of heaven, to the Pushed back earth and brought there to the other damned by the hellkeeper angels.

-

Questioning in the grave: It takes place after the burial and, since the result is already known, it is a kind of show trial. The deceased is tested by two angels, Munkar and Nakir (blue and black), through four questions (Who is your God? Who is your prophet? What is your religion? Where does your prayer point?). If he answers correctly (the answers are noted by a scribe), the angels Mubashar and Bashir take care of him, comfort him and promise him paradise. Otherwise he will be left alone until the Last Judgment. In the case of wrong answers, the dead are already tormented in the grave by the angels Nakir and Munkar by opening a gate to hell in the grave, while the grave is tortured tightly around the dead. This principle of double punishment is not directly documented in the Koran, but it developed early on.