Psychostasis

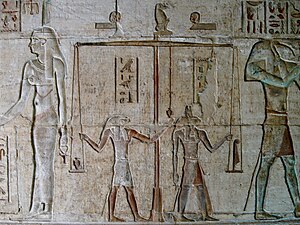

The term weighing of souls ( ancient Greek ψυχή , soul ' + ancient Greek στάσις , stability, Standing, Holding' ) referred to in the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead for the period from the New Kingdom until the Ptolemaic period , the ancient Egyptian belief that the deceased's heart before the unification of its Ba-soul weighed with his corpse in the Hall of Complete Truth . The determined weight is representative of the detachment of the negative acts of the deceased. If the heart was too heavy, indicating the inadequacy of the deceased, it was fed to the corpse eater, Ammit .

Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead

The Book of the Dead verse 125 deals with the description of the ancient Egyptian judgment of the dead . The deceased has to justify himself to the judges of the dead, as they will decide his future fate . This is where psychostasia takes place. At the beginning, the deceased goes to the Hall of Complete Truth to face the 42 judges of the dead in the Book of the Dead and give an account to them.

After saying a short greeting, the deceased begins to give a monologue about the negative acts he has not committed and then turns directly to each of the judges of the dead to deliver his negative confession. Afterwards, the deceased emphasizes again how he distinguished himself during his lifetime and asks the gods to save him. The psychostasis is illustrated by vignettes , the main characteristic of which is the depiction of the deceased in the presence of the scales .

History of psychostasia

For the Greeks in the early heroic lore, it was the tropos of human life in equilibrium in which the gods held the scales to determine the survival of the heroes in a duel, such as during the battle of the heroes Achilles and Hector in the Iliad , when Zeus, tired of the battle, hung up his golden scales and placed the paired Keres in them - "two fateful components of death". This process was a kerostasy, a weighing of the fate of the hero, rather than a judgment of the respective value. This tradition was often cultivated by vase painters. Similar types can be found on later works of art, especially on Etruscan mirrors, for which fiery-like figures appear here.

Among the later Greek authors, psychostasia was the prerogative of Minos , the judge of the newly deceased in the underworld of Greek mythology . Plutarch reports that Aeschylus wrote a tragedy called Psychostasia ( Greek ψῡχο-στασία ) in which the spectators of the fight were Thetis and Eos , which in this case shows the fight between Achilles and Memnon .

The weighing of souls in the Last Judgment corresponds to the Egyptian weighing of hearts in the judgment of the dead. It is also known in the Old Testament (Job 31, 6; Dan 5, 27). In Christianity, the weighing of the soul is only present in the idea of the Last Judgment, in which people are to be judged by God. It is made in medieval representations by the Archangel Michael (see fig.). In Egyptian and medieval images, subordinate elements of the balancing of the soul also faithfully correspond, not least the jaws of the monster as a symbol for hell. Just as the assessors in the Egyptian court were able to recruit themselves from the blessed dead, so the apostles also take part in the Last Judgment alongside “the throne of his glory” (Matt. 19, 28).

In popular belief, the Egyptian tradition of psychostasis lived on. Until the Middle Ages, many Christians adhered to the custom of replacing the heart of a deceased person with something heavier. First, the organic heart used to be removed and replaced with an artificial heart made of a material that was as heavy as possible in order to increase the chance of the dead to continue to live in the afterlife after death or to make their heart appear "heavier". With wealthy people, such as B. Emperors, kings and wealthy nobles preferred gold as a heart substitute. Members of the lower classes replaced the heart with an ordinary stone. Since this custom lasted until the Middle Ages, we also know today the expression "a heart made of gold / stone" from that time. Another explanation for the expression “a heart made of stone” is the Old Testament Bible passage Ez 36,26 EU in which God announces to take away the stone heart of the people and to replace it with a fleshly one.

Idioms

Idioms turn out to be a collective memory for long forgotten ideas. The expression “weighed and found too easy” (= the factual, professional, ethical or similar requirements not sufficient, cf. DUDEN phrases) comes from the Old Testament book Daniel (5, 27), which directly takes up the Egyptian idea of psychostasis . The expressions “light hearted” and “a heart made of stone”, on the other hand, have had a meaning inversion over time. You mean the opposite of the psychostatic origin.

Attempts at Scientific Psychostasia

Duncan MacDougall , a doctor from Haverhill , Massachusetts , determined the weight of the soul to be 21 grams in scientific experiments. The New York Times reported on this on March 11, 1907. MacDougall built a precision balance: a bed suspended from a frame, the weight and contents of which could be determined to within five grams. The first of six subjects showed a weight loss of 21 grams at the moment of death: the supposed weight of the soul. 15 dogs, on the other hand, died on the scales - all without the slightest loss of weight. The Dutch physicist Dr. Zaalberg van Zelst and also Dr. Malta wanted to have proven that the astral body of a person can be weighed and thus physically proven. In some experiments in The Hague, they weighed dying patients and determined an inexplicable weight loss of 69.5 grams for the persons at the moment of clinical death . The film “ 21 grams ” ( Alejandro González Iñárritu , USA 2003) refers to these experiments.

In the 1930s, teacher Harry LaVerne Twining in Los Angeles made experiments with mice, which he killed and weighed as they died. He placed a beaker with a living mouse and a piece of potassium cyanide on each of the bowls of a beam balance and balanced the experimental arrangement. Then he put one of the cyanide pieces in the glass. When the mouse died after 30 seconds, the balance bar moved up on its side. Thus, as with MacDougall's attempt, there was weight loss. But when Twining had the mouse suffocated in an airtight glass cylinder, no change in weight was found. From this, Twining concluded that a dying mouse loses a certain amount of liquid at the moment of death, which evaporates but cannot escape when the vessel is sealed.

Twining's hypothesis is not convincing, however, since a reason for such a sudden and great loss of fluid during the dying process is not apparent. Len Fisher points out that convection currents may play a role; this factor was not considered by either MacDougall or Twining. It could also be the air that escapes from the lungs in the event of death. However, this then had to be observed in all mammals. In the tests with dogs, the thermal insulation created by the fur could have influenced the result. However, if one assumes that the liquid does not evaporate but is caught in the fur, this should also be the case with mice. Fisher therefore states that a satisfactory explanation of the experiments has not yet been found.

See also

literature

- Len Fisher: The attempt to weigh the soul and other great moments of researchers and fantasists. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2005, ISBN 978-3-593-37765-0 .

- Dennis Goldstein: Iron Heart. Origin and change of central European folk customs. Cologne 1989.

- Karin Plashy: The representation of the weighing of souls in the Middle Ages. Supervised licentiate thesis, Institute of Art History, Zurich (summer semester) 2002.

- Rudolf zur Lippe: The seat of the soul. In: Dietmar Kamper, Christoph Wulf: The extinct soul. Discipline, history, art, myth (= historical anthropology series. Volume 1). Reimer, Berlin 1988, ISBN 978-3-496-00946-7 , pp. 162-175.

- Mohammed Saleh: The Book of the Dead in the Theban private graves (= Archaeological Publications. (AV) German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 46). Mainz 1984.

- Ulrich Schnabel: The measurement of faith. Karl Blessing, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-89667-364-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Name variants Ammit and Ammit-net-amentet .

- ↑ The judgment of the dead meets not only in the Book of the Dead, but also in the Amduat and the Book of Portals .

- ^ Iliad , 22, 208.

- ↑ James V. Morrison: Kerostasia, the Dictates of Fate, and the Will of Zeus in the Iliad. In: Arethusa. Volume 30, No. 2, 1997, pp. 276-296.

- ↑ Plutarch , De audiendis poetis (de aud. Poet.) 2; Compare Iliad 22, 210 ff. And the parody by Aristophanes Ranae . 1365 ff.

- ↑ Len Fisher: The attempt to weigh the soul ... Frankfurt 2005, pp. 29–35.