Vinča culture

The Vinča Culture ( vɪnt͡ʃa ) is an archaeological culture of the Neolithic Age in Southeast Europe . It was from 5400 to 4600/4550 BC. BC mainly spread in the area of today's Serbia , also in western Romania , southern Hungary and in eastern Bosnia and today's Kosovo. In the subdivision of the Neolithic, the Vinča culture falls into the south-eastern European Central and Late Neolithic as well as the early Eneolithic . It was founded by Friedrich Holste into the phases of Vinča A-D divided.

Research history

The culture got its name from the locality Vinča Belo Brdo on the right bank of the Danube near Belgrade , near the mouth of the Bolecica River .

Miloje Vasić (Vassits) carried out minor excavations in the 12 m high Tell from 1908 to 1918 . Vasić published his first results as early as 1908.

Later, with financial support from Sir Charles Hyde, a total of 3.5 hectares could be excavated from 1924 to 1936 . The successive layers of the settlement made it possible to establish a chronology of the development of ceramics, although the excavation was not based on archaeological layers, but on artificial strata 10 to 20 cm thick . Since the surface of the settlement mound was seldom completely even and uniformly populated and pits were dug into deeper soil layers at all times, there was a certain mix of finds of different ages.

The following layers are described:

- 9.3 m to 8 m: ceramics from the Starčevo culture ; (Findings of Starčevo and Vinča ceramics are limited to a few pits).

- 9 m to 8 m: Level A.

- 8 m to 6 m (above fire layer): Level B, sometimes divided into B1 and B2

- 6 m to 4.5 m: Level C

- 4.5 m to 3 m: Level D.

Vladimir Milojčić wanted to derive Vinča from the Aegean Early Bronze Age in a publication from 1949 and argued with the sharply profiled vessel shapes and the fluted ornamentation, which for him revealed models made of metal. Since radiocarbon dating had not yet been invented, he erroneously dated Vinča to 2700–2000 BC for stylistic reasons. Also Vere Gordon Childe , who visited the excavations in 1957, saw clear parallels in Vinča ceramics with finds from Troy and therefore dated Vinča to approx. 2700 BC. He differentiated the phases Vinča-Tordoš (Turdas) (level A – B1) and Vinča-Pločnik (level C1 – D2), with an intermediate stage Gradac (B2 / C1).

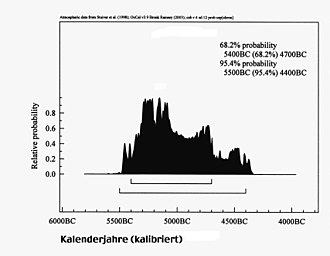

The view that even Neolithic cultures in Europe could not be older than the Old Kingdom in Egypt was held by Milojčić until the widespread acceptance of the radiocarbon method. In the meantime, a number of 14 C dates are available (see figure), which allow a more precise dating.

In 1978 the excavations of Nikola Tasić and Gordana Vujović were resumed. Milutin Garasanin and Dragoslav Srejović have been excavating the Neolithic layers since 1982 .

Culture

Ceramics

A very high quality, mostly unpainted ceramic is typical . The surface is usually smoothed and polished to a shine, sometimes decorated with grooves or fluting . In addition, there are rectangular scratch patterns. Sharply profiled biconical shapes are common. Often there are 2 to 4 lumps on the fold.

The steps by Friedrich Holste (1908–1942) are characterized by the following ceramic features:

- Vinča A: biconic bowls and bowls, mugs with a collar rim, high foot shells, often with a red coating, double-conical vessels with cylinder necks, egg-shaped pots. Decoration by fluting, straight incised patterns.

- Vinča B: Most of the forms from A continue. Rounded incised patterns and ribbons filled with stitches now appear in the decorations.

- Vinča C: pots decorated with spiral grooves and a meander pattern with stitch-filled ribbons. For the first time, button handles and vessels with spouts.

- Vinča D: Vessel shapes resemble C, but now impasto white and red painting with rectilinear patterns.

Clay figures mostly show standing women with large and protruding eyes and a triangular face, which some researchers interpret as a mask. This face shape can also be found in theriomorphic (animal-shaped) figures, so we are dealing with masked cattle. A 20 cm long mask made of lightly fired clay was found in Uivar in 2001 . Human and animal heads made of clay are interpreted as the gable decoration of the houses. During the younger Vinča stages there are also clay figures showing seated figures. There are also human and animal-shaped vessel lids, which are mostly decorated with incised lines and show the same bulging eyes as the idols.

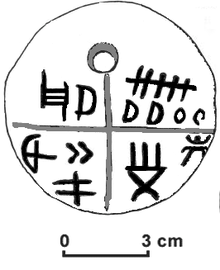

Vinča sign

On some of the idols there are individual incised lines that are interpreted as pottery or owner's marks. Some researchers wanted to derive an early form of writing from this. As early as 1903, Hubert Schmidt tried to derive 'signs' from Turdaș from the Egyptian hieroglyphs from finds from Troy . Vasić believed in a Greek origin. Before the general use of radiocarbon dating, Vladimir Milojčić pleaded for a derivation of this alleged script ( clay tablets of Tărtăria ) from the archaic characters of Uruk ; it is now known that these are almost a thousand years younger. Vladimir Popović in particular made the thesis of an early (Serbian) high culture popular with its own script. Since writing usually appears when major administrative tasks are involved (warehousing and tax collection), it is very unlikely that this simple peasant culture had any use for it.

Stone and bone tools

Long, regular blades are typical of the Vinča culture. Obsidian from Semplen was often used to manufacture equipment, and high -quality “Balkan” honey-yellow flint was also imported. Towards the end of the Vinča culture, imports decrease significantly. Axes are generally rare and often very small. Bone idols and often heavily worn spoons ( spatulae ) from cattle metapodia are also known from the Vinča culture . Band ceramic bone idols, such as those found in Niedermörlen , are derived from these . Pieces of jewelry were made from the shell of the spondylus shell .

Settlements

The settlements are mostly located on tells (settlement mounds), which can be between 3 m and 12 m high and are sometimes fortified by trenches (Uivar). Flat settlements are also known, even if hardly explored. The rectangular, sometimes multi-roomed houses had floors made of thin tree trunks that are covered with screed , the walls are made of wickerwork smeared with clay, which perhaps sometimes had plastic decorations. In Romania, swell structures are sometimes accepted because there are no post holes.

In the houses there were stoves and ovens, which were often replaced. What the roof looked like is unknown. Since there are no supporting posts inside the house, it must have been quite light and may have been made of wood shingles or bark. The houses were arranged quite regularly along the streets. Houses destroyed by fire are very often found, which led Ruth Tringham to speak of a chronological horizon of "burned houses". Perhaps the buildings were deliberately set on fire when a family member died.

Burials

Grave fields are not yet known.

Cult places

At Parța in Romania, an altar room 11.5 meters long and 6 meters wide was found, which consists of two parts, the altar chamber and the sacrificial site ( sanctuary of Parța ). On the altar there are two statues , a female deity and a bull , a symbol of fertility according to Lazarovici . The temple probably also served as a calendar . Exactly at the time of the equinox , the light fell through a crack and illuminated the altar. Pottery vessels were also found in the chancel.

economy

As for domestic animals, besides dogs, cattle, sheep, goats and pigs were known. In Liubcova as in Uivar , cattle dominated. The dog was apparently also eaten, numerous bones with slaughter marks are found from Liubcova. In addition, red deer, wild ass, roe deer, ur, beaver and some other wild animals were hunted, which is unclear, arrowheads made of flint are unknown. The most important crop was einkorn , a primitive type of wheat; emmer , naked wheat , hulled barley , peas, lentils and flax were also grown. Collective plants such as hazelnuts, sloes , cornel and white goosefoot were also used.

The cinnabar mine of Šuplja Stena on Avala Mountain is often assigned to the Vinča culture, as all layers of Vinča contain cinnabar, which was probably used as a dye. Finds from the mine itself, however, only date from the Late Copper Age Baden culture and the Middle Ages.

interpretation

The Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas counted the Vinča culture among the old European cultures , which were destroyed or assimilated by an invasion of patriarchal " Kurgan peoples " from the east , which she connected with the Proto-Indo-Europeans .

Today archaeologists see rather social changes (John Chapman (1981, 2000)) or a climatic change as the reason for the end of the Vinča culture.

Important sites

- Anza-Begovo

- Divostin near Kragujevac , Serbia

- Grivac near Kragujevac, Serbia

- Opovo near Belgrade, Serbia. Excavations by Ruth Tringham 1983–1987.

- near Parța in Timiș County , Romania, Sanctuary of Parța

- Potporanj near Vršac , Serbia

- Selevac near Kragujevac, Serbia. Excavations by Ruth Tringham

- Uivar , Banat, Romania, excavations by the University of Würzburg (Wolfram Schier) since 1998

- Vinča , Serbia

- Tărtăria , Romania

- Pločnik , Serbia. Oldest smelted copper objects.

Paleogenetics

With the paleogenetic examination of the haplogroup of the Y chromosome , the common ancestors can be traced in a purely male lineage, because the Y chromosome is always passed on from father to son. A haplogroup is a group of haplotypes that have specific positions on a chromosome. The paternal line is found on the Y chromosome (Y-DNA) and the maternal line on the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

The haplogroup G2a (Y-DNA) comes from the Caucasus region and probably came to Europe with the early Neolithic, i.e. agriculture, cultures. Most of the investigated skeletal finds from the Starčevo and Vinča cultures on the Balkan Peninsula , as well as members of the linear ceramic culture , belonged to the Y-haplogroup G2.

literature

- Dušan Borić: Absolute dating of metallurgical innovations in the Vinča Culture of the Balkans. In: Tobias L. Kienlin; Benjamin W. Roberts (Ed.): Metals and Societies. Studies in Honor of Barbara S. Ottaway , Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt, Bonn (2009), pp. 191–245.

- Florin Draşovean: The Vinča culture, its role and cultural connections. International Symposium on the Vinča Culture, its Role and Cultural Connections. Banat National Museum , Timișoara 1995 (= Bibliotheca historica et archaeologica banatica 2).

- Milutin Garašanin: Hronologia vinčanske grupe. Belgrade 1951.

- Friedrich Holste : On the chronological position of Vinča ceramics. In: Viennese prehistoric magazine. 27, 1939, 1-21.

- Vladimir Milojčić: The prehistoric mine “Šuplja Stena” on Avala Mountain near Belgrade (Serbia). In: Wiener Prehistorische Zeitschrift 1937, 41–54.

- Erika Qasim: The Tărtăria tablets - a reassessment. In: Das Altertum 58 (2013), pp. 307-318.

- Erika Qasim: Sitting outside, listening and banishing. In: Das Altertum 61, 2 (2016), pp. 133–150

- Robert J. Rodden: The Spondylus-shell trade and the beginnings of the Vinča culture. In: Actes du VII e Congrés International des Sciences Pré- et Protohistoriques. Prague, 1970, pp. 411-413.

- Wolfram Schier : masks, people, rituals. Würzburg 2005 (catalog).

- Nikola Tasi, Dragoslav Srejović, Bratislav Stojanović: Vinča, Center of the Neolithic culture of the Danubian region. Belgrade 1990.

- Ruth E. Tringham, Bogdan Brukner, Timothy M. Kaiser, Ksenija Borojević, Ljubomir Bukvić, Petar Steli, Nerissa Russell, Mirjana Stevanovic, Barbara A. Voytek: Excavations at Opovo, 1985–1987. Socioeconomic Change in the Balkan Neolithic. In: Journal of Field Archeology 19, No. 3, 1992, pp. 351-386.

- Miloje Vasić: Preistorijska Vinča II – IV. Belgrade 1936.

- Ian Shaw, Robert Jameson: A Dictionary of Archeology. Wiley, 2002, ISBN 0631235833 , p. 606 ( excerpt (Google) )

Web links

- Vinča symbols at omniglot.com, including font

- Eric Lewin Altschuler: The Number System of the Old European Script

- Uivar excavation of the Free University of Berlin

- Excavation Opovo (English) ( Memento from September 2, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Vinca excavation (English)

- http://www.rastko.org.rs/arheologija/vinca/vinca.html Guide to Vinča (Serbo-Croatian)

Individual evidence

- ^ Dušan Borić, The End of the Vinča World: Modeling the Neolithic to Copper Age transition and the notion of archaeological culture. In: Svend Hasen et al. (Eds.), Neolithic and Copper Age between the Carpathians and the Aegean Sea. Archeology in Eurasia 31. Bonn, Habelt 2015, p. 163

- ^ Mihael Budja: The transition to farming in Southwest Europe: perspectives from pottery. Documenta Praehistorica XXVIII, pp. 27–47 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ M. Stevanović: The Age of Clay. The Social Dynamics of House Destruction. In: Journal of anthropological Archeology. 16, 1997, pp. 334-395 ( doi : 10.1006 / jaar.1997.0310 ).

- ^ [1] , Sanctuarul Neolitic de la Parta

- ^ John Chapman: The Vinča culture of south-east Europe: Studies in chronology, economy and society. 2 vols, BAR International Series 117. (1981). Oxford: BAR. ISBN 0-86054-139-8

- ↑ John Chapman: Fragmentation in Archeology: People, Places, and Broken Objects. Routledge, London 2000, ISBN 978-0-415-15803-9