Cahokia

| Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| Monk's Mound is the largest earth pyramid north of Mexico |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (iii) (iv) |

| Surface: | 541 ha |

| Reference No .: | 198bis |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1982 ( session 6 ) |

| Extension: | 2016 |

Coordinates: 38 ° 39 ′ 17 " N , 90 ° 3 ′ 34" W.

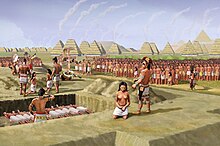

Considered the main center of Mississippi culture, Cahokia was the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico . The city measured nearly five kilometers from west to east and over 3.5 kilometers from north to south, and covered an area of over 15 square kilometers . The park, in which the former city is located, covers an area of 390 hectares .

Cahokia was produced by what is known to be a scriptless culture. The city was not far from today's St. Louis in the US state of Illinois . It existed from around AD 700 and was a planned city . By 1000, their population rose rapidly, possibly because the emerging corn cultivation provided a safer and more abundant food source. But other foods, such as amaranth , could also be detected. The residents of Cahokia grew food on an area estimated at 13 square kilometers.

Estimates of the population range from 8,000 to 20,000, sometimes up to 40,000. In addition, many finds point to a hierarchy of society. The lords of the city lived in houses on some of the up to 120 mounds . Others of them served as burial places.

Surname

The name of the city is not known. Instead, it was named by Europeans after a group of Illinois , the Cahokia Indian tribe , who lived in the region at the time , but which only appeared there long after the fall of Cahokia.

Mounds, urban structure

The mounds extended over an area of 15 square kilometers. In the center of the city was an area of 81 hectares, which was surrounded by a 3.2 kilometer long and 3.6 meter high wall made of wooden blocks and enclosed 17 mounds. In the center of it was the largest of the Monks Mound , a 30.6 meter high, flattened earth pyramid , which covered an area of 291 by 236 meters, i.e. over five hectares. Around this protected central area, thousands of people lived in groups, the center of which were ceremonial stakes.

The truncated pyramid, named Monks Mound after a nearby Trappist monastery, is the largest man-made structure from pre-Columbian times north of Mexico. It is estimated that 14 million baskets of earth had to be moved to gradually build up the 692,000 cubic meter mound. Over 200 years, four steps were created, each of which was interspersed with canals to drain away the rainwater. On top of the mound stood a wooden building measuring 31 by 14 meters and a height of 15 meters. In 1998 a sandstone layer was discovered about twelve meters below the surface of the mound. These large quantities of sandstone cannot come from the region, so they must have been transported over greater distances.

The planning of the city represented an attempt to reflect the order of the world, with a northern part as Father Heaven and a southern part as Mother Earth. These were separated by a road running west-east. Another main road ran northeast. Their intersection was at the central plaza, the main plaza with the largest mound. At the far ends of the streets were four circles of logs (red cedar), the arrangement of which appeared to be for astronomical purposes.

A man about 40 years old who had died around 1050 was found under Mound 72. He was buried under 20,000 shells and 800 unused arrows. With him, four men were found with their hands and heads cut off, as well as 53 strangled women, aged 15 to 25 years. A total of 280 skeletons have been excavated so far, 50 of them in a deep well alone - many of them were obviously injured before they died. It is probably about human sacrifices , as they are known by the Aztecs .

Woodhenge

The excavations have shown that they were engaged in astronomy . Archaeologists therefore spoke of “Woodhenge” because, similar to the English Stonehenge, wooden stakes were used to determine the spring and autumn equinoxes , thus developing a kind of calendar. In a rural society, determining the seasons and the dates of sowing and harvesting is of the utmost importance. After Woodhenge was discovered during road works, it was decided to move State Road 55 further east.

Long distance trading and processing

The city possibly controlled a trade in flint , copper, and shells that reached far north to Minnesota . Cahokia's trade reached as far as Kansas in the west and Tennessee in the east. Raw materials came to the city and were refined there. These products in turn reappeared in a wide area, so that one assumes a trading network.

Population growth, city fortifications

It is unclear why the inner city, possibly the home of the leadership groups, was surrounded by a large wall in the 11th century, which was secured by a watchtower every 70 m. Apparently this happened in a big hurry, because it also cut through inhabited areas. The growth of the places in the distant area around 1200 can be proven, which may have prompted Cahokia to build the larger wall. In any case, the inner wall was renewed three times by 1300.

The archaeologist Timothy Pauketat suggested that in the 11th century Cahokia grew explosively within a few decades, so that a larger settlement with perhaps 1000 inhabitants suddenly became a city with well over 10,000. In fact, there is evidence in local lore that the farmers in the scattered settlements of the region left their villages on the initiative of a great chief to live in Cahokia. The chiefs were therefore considered to be the brothers of the sun , and it is believed that they originally supervised the floodplains, which were supplied with fertile mud every year by the floods, and organized the necessary work.

Decline

After 1200 Cahokia began to decline, the reasons for which are unclear. Ecological reasons were often mentioned in connection with the excessive demands placed on the area by maize cultivation, which could have led to severe deforestation. It turns out that more and more softwoods had to be used for construction, perhaps because the hardwood stocks were cut down. The overburdening of the urban infrastructure by the rapidly growing population was also considered. A civil war or the destruction of one of the large mounds by a mudslide may have been the cause.

It is ultimately not known why the city was finally abandoned around 1400. The population decreased significantly, Cahokia became meaningless, eventually abandoned.

Discovery and Endangerment

When the first Europeans came to the area, they thought the hills were natural phenomena, the great mound was first described in 1810. Agriculture, industrial waste and exhaust gases and road construction are still less of a threat to the central site than the surrounding smaller settlements.

World Heritage

Since the 1960s, excavation campaigns have made the city's importance increasingly clear. The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site is part of since 1982, World Heritage of UNESCO , has its own museum, is housed in a 890-hectare park, which is administered by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, and is publicly available. The connection with today's Indians is unclear, but the city (again) seems to enjoy a certain veneration.

See also

literature

- Timothy R. Pauketat, Thomas E. Emerson: Cahokia. Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World , University of Nebraska Press 1997.

- Thomas E. Emerson and R. Barry Lewis (eds.): Cahokia and the hinterlands: middle Mississippian cultures of the Midwest , Urbana: University of Illinois Press 2000.

- William R. Iseninger: Cahokia Mounds. America's First City , Charleston: The History Press 2010.

- Biloine Young, Melvin Fowler: Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis . Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois 2000 ISBN 0-252-06821-1

- Melvin L. Fowler: The Cahokia Atlas. A Historical Atlas of Cahokia Archeology , Urbana 1997 (revised edition of the 1st edition from 1989)

- Timothy R. Pauketat: Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians , 2004.

- George R. Milner: Cahokia Chiefdom: The Archeology of a Mississippian Society , Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington 1998, ISBN 1-56098-814-2 .

- Biloine Whiting Young, Melvin L. Fowler: Cahokia, the Great Native American Metropolis , Champaign: University of Illinois Press 1999.

- John E. Kelly, James A. Brown: Cahokia. The Processes and Principles of the Creation of an Early Mississippian City , in: Andrew T. Creekmore III, Kevin D. Fisher: Making Ancient Cities. Space and Place in Early Urban Societies , Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 292–356.

Web links

- Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site - Official Site

- Angelika Franz: America's mysterious megacity . Spiegel Online, May 6, 2008

- University of Bayreuth - Geoecology: William Woods: Cahocia Soils ( Memento from June 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) - Changes in the Mississippi river bed as the cause of the end of Cahokia (English)

- www.indianerwww.de: Cahokia

- Cahokia Site Mounds Listed by Common Name

- interactive map of "old Cahokia"

- Article in the Washington Post

- Cahokia. America's Forgotten City , in: National Geographic, January 2011.

- KETC | Living St. Louis | Cahokia Archeologists , report from 2008

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cahokia mounds. Illinois , in: Donald Langmead, Christine Garnaut (Eds.): Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Feats , 2001, pp. 49–52, here: p. 52.

- ↑ Young & Fowler, 2000, pp. 270 f

- ↑ Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site: Mound 72 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed June 30, 2011)

- ^ John Man: Atlas of the year 1000 , Harvard University Press, 1999, p. 20.