Taos Pueblo

| Taos Pueblo | |

|---|---|

Taos Pueblo |

|

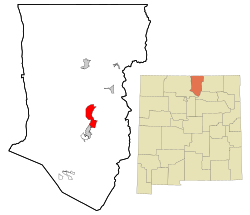

| Location in New Mexico | |

| Basic data | |

| State : | United States |

| State : | New Mexico |

| County : | Taos County |

| Coordinates : | 36 ° 26 ′ N , 105 ° 33 ′ W |

| Time zone : | Mountain ( UTC − 7 / −6 ) |

| Residents : | 1,264 (as of: 2000) |

| Population density : | 31.2 inhabitants per km 2 |

| Area : | 40.5 km 2 (approx. 16 mi 2 ) of which 40.5 km 2 (approx. 16 mi 2 ) is land |

| Height : | 2170 m |

| Postal code : | 87571 |

| Area code : | +1 575 |

| FIPS : | 35-76410 |

| GNIS ID : | 0928824 |

| Website : | taospueblo.com/index.php |

Taos Pueblo is believed to be the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in the United States . The pueblo is one of the Eight Northern pueblos whose residents speak one of two variants of the Tanoa language . The village consists of two pueblos and is located in the north of the US state New Mexico in Taos County in the Taos Indian Reservation on both sides of the Rio Pueblo , which is also called Red Willow Creek . Around 150 Indians of the people, also known as Taos , live in the two main buildings in a largely traditional way of life. In 1992, UNESCO declared Taos Pueblo a World Heritage Site . Taos Pueblo is also a census-designated place with 1264 inhabitants (status: 2000), of which 95% are indigenous , and an area of 40.5 km² around the settlement.

Taos Pueblo is a tourist attraction. The residents' monetary income comes mainly from tourism and the sale of works of art and handicrafts , which are mainly sold to visitors. Traditional agriculture for self-sufficiency is also still important.

Surname

Tanoa

In the Taos dialect of the Tanoa language, the pueblo is simply referred to as the "village", with the forms tə̂otho "in the village" ( tə̂o- "village" + -tho "in") or tə̂obo "to the village" ( tə̂o- " village "+ -bo " zu, zum ... hin "). The proper name, however, is ȉałopháymųp'ȍhə́othə̀olbo "At the mouth of the Red Willow Canyon" (or ȉałopháybo "At the red willows" as a short form). The name is used more for ceremonial contexts and rarely occurs in everyday language.

Spanish

The name Taos probably goes back to Tanoa ' tə̂o- . The plural -s was originally added to the Hispanic tao . However, the plural meaning is unknown in the contemporary language. Less often one encounters the idea that Taos goes back to tao = "Cross of the Order of San Juan de los Caballeros" (from the Greek τ tau , St. Anthony's Cross ).

history

The oldest parts of today's buildings date back to the Anasazi culture and were built between 1000 and 1450. The pueblo was built on the slope of the Taos Mountains in the Sangre de Cristo Range .

Time before the European discovery

Most archaeologists assume that the Taos Indians settled along with other Pueblo Indians after a migration from the Four Corners region along the Rio Grande . The residential buildings in the region were built by the Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloans). Possibly a long drought in the late 13th century caused the Puebloans to migrate to the Rio Grande, where the water supply was more reliable.

In the early days, the Taos Pueblo was a central trading post between the residents of the Rio Grande catchment area and the neighboring prairie Indians in the northeast. In autumn it was the venue for a "fair" after the harvest.

Spanish settlement period

The first Spanish visitors reached the Taos Pueblo in 1540; Members of the Francisco Vásquez de Coronado expedition visited many of the pueblos in what is now the southwestern United States in search of the legendary " Seven Golden Cities ". Fray Francisco de Zamora founded the mission in 1598 on the orders of the Spanish governor, Don Juan de Oñate . Around 1620, Spanish Jesuits led the construction of the first Catholic church within the pueblo, the Mission de San Geronimo de Taos . Reports from this period indicate that the residents resisted the building of the church and the compulsion to join the Catholic religion. Throughout the 16th century there was growing tension between the natives and the increasing presence of Spanish colonialists. In 1660, for example, the residents killed the local priest and destroyed the church. A few years later it was rebuilt. In 1680 the Pueblo uprising began , in the course of which the church was again destroyed and two local priests were killed.

At the turn of the 18th century, San Geronimo de Taos was rebuilt for the third time. The relationship between Spaniards and Taos was even friendly for a short time, as both groups had to unite against a common enemy: Ute and Comanches advanced into the area. The rejection of Catholicism and Spanish culture, however, remained strong. Even so, the Spanish religious ideas and agricultural methods slowly acculturated the Taos culture, reinforced by closer cooperation.

American time

Taos uprising

The Taos Revolt began at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1847. The Mexican patriot Pablo Montoya and Tomasito , a leader of the Taos Pueblo, led a militia made up of Mexicans and Taos who fought against the annexation to the United States. They killed Governor Charles Bent and others and marched on Santa Fe . The uprising was put down and the pueblo besieged. The rebels sought protection in the mission church. The Americans shelled the church, killed or captured the insurgents and destroyed the building. Around 1850 a new church was built near the western gate of the Pueblo Wall. The ruins of the former church and the successor building from 1850 can be seen in the pueblo to this day. Father Anton Docher first lived as a priest in Taos before he served as a priest in Isleta , where he was given the honorary name "The Padre of Isleta".

20th century

1924-25, the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung visited Taos Pueblo and studied traditional culture under the guidance of Ochwiay Biano (Antonio Mirabal, Mountain Lake), because he assumed that natural societies would have more direct access to archetypes .

The approximately 19,000 hectare mountainous land that belongs to the Pueblo was expropriated by President Theodore Roosevelt and designated as Carson National Forest . In 1970 it was returned to the Indians by Richard Nixon under Public Law 91-550 . Another area of 764 acres (309 hectares) south of the ridge between Simpson Peak and Old Mike Peak , west of Blue Lake was returned to the community in 1996.

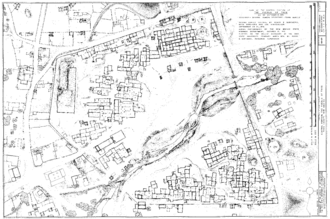

architecture

The buildings are made of adobe adobe bricks . At the time of the first encounters between the Spaniards and the pueblo, Hernando de Alvarado described the building complex “mud houses that are built very close to one another and are five to six stories high”. The houses became narrower towards the top, so that the roofs on each floor formed forecourts and terraces for the rooms above.

The buildings originally had only a few windows and no uniform doors. The rooms were accessed via square holes in the roofs, which the residents reached via long wooden ladders. Cedar trunks ( vigas ) stabilized the roofs, which were covered with layers of branches, grass, mud, and clay. The architecture and building materials were adapted to the environment and the needs of the people.

The first Spanish influences came to the pueblo with Fray Francisco de Zamora.

Main complex

The north side of the pueblo is one of the most-photographed and painted buildings in North America. It is also the largest multi-story pueblo structure that still exists and is inhabited. The clay walls are often over a meter thick. The main purpose used to be defense. Until around 1900, access to the rooms was only made possible by ladders - both from the outside via the roofs and inside. In the event of an attack, the ladders could easily be pulled up.

Apartments

The apartments usually consist of two rooms. One of these is usually used as a living room and bedroom, the other as a kitchen, dining room and grocery store. Each apartment is self-contained; there are no transitions to other apartments. The Taos used little furniture in the past. Today, however, tables, chairs and beds are also used. Electricity, running water, and sewers are still banned throughout the Pueblo today.

religion

Over 90% of the residents officially describe themselves as Roman Catholic . In fact, the traditional rites of their local religion still play an essential role. Details of their religious beliefs and practices are not accessible to outsiders. The interior of their Catholic church " San Geronimo Chapel" may not be photographed. During larger celebrations that take place annually at the end of August - and possibly at other times - access to the entire area is prohibited for strangers. Saint Jerome (Geronimo) is the patron saint of the pueblos.

Blue Lake

The return of sacred Blue Lake and the adjacent land to the northeast of the settlement and southeast of Wheeler Peak in 1970 and 1996 was a significant step on the road to Indian self-government . The Blue Lake is the central sanctuary of the Taos people and the place of their creation story. The area was separated from the reservation in 1906 and given to the United States Forest Service . Longstanding protests by the Indians were answered by bans on traditional religious practice in the area. The reason given was the use of the plant drug mescaline , which has always played an important spiritual role in the religions of the cultural area of the south-west . It was not until President Richard Nixon recognized the importance of the land for the indigenous peoples and transferred the lake back to the Taos in September 1970. The Taos consider this move to be the most important event in their recent history. The area was expanded by law in 1996. It serves exclusively the cultural customs of the Taos, access is prohibited to outsiders. The recognition of the rights of the Taos in 1970 is considered a forerunner of the Indian Self Determination Act of 1975.

In the media

The writer and poet Nancy Wood was inspired by indigenous culture through a stay in Taos Pueblo.

See also

literature

- Elsie Clews Parsons : Taos Pueblo . Banta, Menasha 1936.

- John J. Bodine: Taos Pueblo: A Walk Through Time. Tucson, Rio Nuevo Publishers 1996. ISBN 9781887896955

- Tisa Joy Wenger: We Have a Religion: The 1920s Pueblo Indian Dance Controversy and American Religious Freedom. University of North Carolina Press 2009. ISBN 9780807832622

Web links

- Official homepage .

- Indianpueblo.org — Indian Pueblo Cultural Center: Taos Pueblo

- unesco.org: Taos Pueblo - UNESCO World Heritage Center .

- Sacredland.org: Taos Blue Lake

- Princeton.edu: Taos Blue Lake Collection - at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University .

- National Park Service — NPS: Taos Pueblo - NPS “Discover Our Shared Heritage” website .

- SMU-in-Taos: Research Publications digital collection - SMU-in-Taos (Fort Burgwin) campus; anthropological + archaeological monographs + edited volumes.

- SMU-in-Taos: Taos archeology

- SMU-in-Taos: Papers on Taos archeology

Individual evidence

- ^ "Taos Pueblo" , Taos website

- ↑ Entry on the website of the UNESCO World Heritage Center ( English and French ).

- ^ William C. Sturtevant: Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 9: Southwest. Government Printing Office 1978: 267. ISBN 9780160045776 online

- ^ William Jones: Origin of the place name Taos. Anthropological Linguistics, 2 (3), 1960: 2-4; George L. Trager: The name of Taos, New Mexico. Anthropological Linguistics, 2 (3), 1960: 5-6.

- ↑ a b c d Pueblo de Taos. In: National Geographic Society 2012

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Taos Pueblo. National Park Service 2012.

- ↑ Leo Crane. Desert Drums: The Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1540-1928 . Rio Grande Press, 1972.

- ↑ Timothy C. Thomason: Lessons of Jung's Encounter with Native Americans. The Jung Page. Northern Arizona University. September 28, 2017; CG Jung in Taos: A Creative Mis-Encounter. David Barton, 2014.

- ↑ B. Julyan: New Mexico's Wilderness Areas: The Complete Guide. Big Earth Publishing, 1999: 73

- ↑ Public Law 104–333 ( Memento of the original dated October 31, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. July 19, 2008.

- ^ Sylvia Rodríguez: The Matachines Dance: A Ritual Dance of the Indian Pueblos and Mexicano / Hispano Communities. Sunstone Press 2009: 17. ISBN 9780865346345 online

- ^ Sascha T. Scott: Paintings of Pueblo Indians and the Politics of Preservation in the American Southwest. ProQuest 2008: 25th ISBN 9780549890423 online

- ^ Marcia Keegan: Taos Pueblo and Its Sacred Blue Lake: Reflections on the Fortieth Anniversary from Members of Taos Pueblo. Clear Light Pub. 2010. ISBN 9781574160994

- ↑ Taospueblo.com: Blue Lake 40th Anniversary , accessed August 13, 2010

- ↑ John J. Bodine: Blue Lake: A Struggle for Indian Rights. In: American Indian Law Review, 1973.

- ↑ Tom Sharpe: Nancy Wood, 1936-2013: Writer, photographer found new 'way of being and seeing' in New Mexico . In: Santa Fe New Mexican March 13, 2013.