Glacier National Park (United States)

| Glacier National Park | ||

|---|---|---|

| St. Mary Lake with a striking mountain range | ||

|

|

||

| Location: | Montana , United States | |

| Next city: | Kalispell | |

| Surface: | 4,100.8 km² | |

| Founding: | May 11, 1910 | |

| Visitors: | 2,965,309 (2018) | |

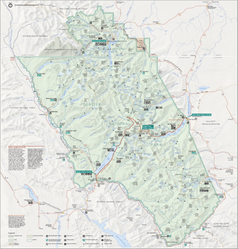

| Detailed map of Glacier National Park (United States) and Waterton Lakes National Park (Canada) | ||

The Glacier National Park is a national park in the United States in the high mountains of the Rocky Mountains . It is located in the north of the US state of Montana on the border with Canada and has geological, geographical and climatic features. Its various ecosystems are almost undisturbed. It was placed under protection on May 11, 1910, is administered by the National Park Service and, because of its long history of research, serves as a reference area for studying the history of the climate and global warming .

Across the border lies the Waterton Lakes National Park on Canadian soil . Both parks together were designated an " International Peace Park " in 1932 as the first cross-border nature reserve in the world under the name Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park , and in 1995 they were declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO . Glacier National Park has been a biosphere reserve since 1976 . Park and region are referred to as the Crown of the Continent , the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem encompasses the large ecosystem of the central Rocky Mountains on both sides of the border far beyond the national parks.

Glacier National Park takes its name from the landscape that was shaped by glaciation during the Ice Age . The glaciers in the park today have only a fraction of their former area and have been falling massively since around 1850 as a result of global glacier melt due to climate change . In the Canadian province of British Columbia there is another national park called Glacier , in Alaska is Glacier Bay National Park .

Geography and climate

The park is located on the eastern flank of the Rocky Mountains and includes their main ridge running in a north-south direction. The continental watershed runs along the main ridge and the Triple Divide Peak lies in the Glacier National Park at an altitude of 2,433 m . The mountain is the watershed point on whose flanks the catchment areas of the Pacific Ocean , the Atlantic Ocean over the Gulf of Mexico and the Arctic Ocean over the Hudson Bay touch. The designation as the crown of the continent for the park and the region goes back to this function as the apex of North America.

The western boundary of the park is the North Fork and Middle Fork of the Flathead River ; the southern border runs along its tributary Bear Creek . In the east the park borders on the Indian reservation of the Blackfoot Indians with the distinctive Chief Mountain on the border, in the north on Canada. The highest point of the park is Mount Cleveland with 3190 m in the north, the lowest point is with 960 m at the confluence of the North Fork and Middle Fork of the Flathead near the west entrance of the park with the headquarters of the administration. In the south run the Great Northern Railway and the US Highway U.S. 2 at or near the park boundary. Outside the park, the Flathead National Forest to the west and the Lewis and Clarck National Forest to the southeast , two national forests under the administration of the US Forest Service . The Great Bear Wilderness , which is only separated from the park by rail and road, is embedded in the two national forests, a wilderness area and thus the strictest class of nature reserves in the United States. On the Canadian side, in addition to the Waterton Lakes National Park in the province of Alberta , the Akamina-Kishinena Provincial Park in the province of British Columbia borders the Glacier National Park.

The appearance of the national park is shaped by the trough valleys , which run across the main ridge and are carved out by ice age glaciers, with over 750 lakes, of which only 131 have an official name. In the lower areas there are tongue basin lakes , in the higher terrain there are cirque lakes . The park's larger lakes are Lake McDonald , Two Medicine Lake , St. Mary Lake , Lake Sherburne and the southern portion of the transboundary Upper Waterton Lake .

The main ridge of the Rocky Mountains separates the park as a climatic divide into two very different zones. The west is subject to the maritime influence of the Pacific Ocean with moderate temperatures and high rainfall, while the east side is part of the continental climate , which is characterized by extreme seasonal temperature differences and the blizzards from northern directions typical for North America . In the east of the park in 1937 at Two Medicine Lake +47 ° C was measured, south of the park on Rogers Pass 1954 -57 ° C, the lowest temperature in the United States outside of Alaska . With this temperature range, Montana is the state with the largest measured temperature difference. In Browning, east of the park, on January 23, 1916, the temperature fell from 7 ° C to −49 ° C in 24 hours, the largest temperature difference in a day in the United States.

geology

The Glacier National Park is geologically raised by the Lewis Thrust . Due to this thrust , very old rock from the Proterozoic , which was formed up to 1.5 billion years ago, lies over younger layers of Quaternary and Cretaceous and the last 100 million years. In the course of the Laramian mountain formation , plate tectonic processes built up pressure off the North American west coast. This was passed on to the east into the North American Plate and a tectonic blanket of around 450 kilometers in length in north-south direction and a thickness of at least 5000 meters was extended by around 80 kilometers at a shallow angle in the period from 80 to 40 million years ago Pushed east over the rock there . Tensions within the ceiling led to a syncline , a concave - i.e. inwardly - arched structure through which the rock layers in the east and west of the park are higher than in the center. They form the park's two north-south mountain ranges, the Lewis range in the east and the Livingstone range in the northwest. Due to this special formation, the Lewis range in the east stands out from the Great Plains without promontories .

The erosion of the upper layers of the Lewis Thrust and the formation of a valley during the glaciation exposed the rocks from the Proterozoic and honed its geological profile . Over 2100 meters in altitude in eight stratigraphic layers are exposed in the park, which makes the area the best research area for the physical and chemical composition of Proterozoic rocks and thus the environmental conditions on earth between 1.5 billion and 900 million years ago worldwide.

The origin of the older rocks in the park are clastic sedimentary rocks . From the deposits of sands , clays and the limestone shells of zooplankton in an ancient sea, rocks such as sandstone , slate and limestone were initially formed . Parts of it were transformed into metamorphic rocks such as quartzite , clay slate as well as crystalline limestone ( marble ) and dolomite over geological time periods by the pressure of later layers . Compared to outcrops of Proterozoic rocks in other parts of the world, the slight disturbance should be emphasized: in the Glacier-Waterton area, details of the sedimentation such as millimeter-precise stratification, ripple marks , impressions of salt deposits, oolites , clay breccias and other shapes have been preserved. The younger quaternary and chalk rocks are only exposed in the east of the park and consist of sandstone and siltstone . In between, rocks from around 800 million years ago are missing; they were already eroded by erosion before, during and after mountain formation.

The different rock layers contain fossils . When Proterozoic rocks came into being, life on earth was only in early forms. Stromatolites from fossilized biofilms of cyanobacteria are preserved in all Precambrian rocks in the park and are particularly common in the Siyeh Formation of dolomite and limestone , which make up the majority of the higher peaks in the park. In the younger Precambrian strata, fossils of first seaweed and four species of invertebrates also occur. Fossilized mussels and snails are found in the quaternary rocks . In the Appekunny Formation in the east of the park, which is dated to an age of 1.5-1.3 billion years, imprints were found in 1982, which the discoverers interpreted as Metazoa and, according to new investigations in 2002 , were described as Horodyskia moniliformis . They are among the earliest traces of multicellular animals in the world.

Ecosystems

The Glacier National Park as the center of the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem is almost unaffected by modern human interventions in the habitats and the flora and fauna. As far as is known , only three animal species have died out in the park since 1492, the year Christopher Columbus landed and a reference point for natural and cultural conditions without European influence: the American bison and the pronghorn, as herd animals of the prairie , formerly touched the far east of the park. The Swift Fox ( Vulpes velox ) was eradicated as predatory game in the 1930s . The information on whether caribou of the subspecies Rangifer tarandus caribou (Canadian forest caribou) ever used the middle altitudes of the eastern flank is inconsistent . Altogether over 70 mammal species live in the area , around 250 bird species and over 1130 plant species have been identified. The fish fauna of the park suffers that were naturalized at the end of the 19th century and until 1971 non-native species in the park to the area for anglers to make it more attractive. However, no species was completely displaced from the park by the artificial stocking, and the natural fauna is preserved in most of the highest lakes.

Five species in the park, bald eagle , grizzly , timber wolf , Canadian lynx and bull trout ( Salvelinus confluentus ) are classified as "Endangered" under the Endangered Species Act . The timber wolf of the northern Rocky Mountains was briefly removed from federal protection by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in April 2009 and transferred to the jurisdiction of the states. A federal court restored the protection in August 2010 because the delisting failed to understand the relationships between the populations in the Rocky Mountains.

The exact number of grizzly bears living in the park is not known. Park biologists estimate the number at around 350. The number of American black bears is significantly higher at at least 800. The population estimates of the black bear vary greatly: A DNA study that evaluated bear hair indicates a black bear population up to 6 times higher.

The park has different ecosystems according to the altitude levels . Around 55 percent of the area is forested, the rest consists of grassland in the lowlands (8 percent), water areas and wetlands (8 percent) and the alpine mats and bare rock in steep walls and above the tree line (29 percent). Because of the climatic differences between the maritime influenced western side and the continental eastern flank, the transitions between the respective ecosystems on the eastern side with its more severe winters are deeper.

Prairies

In the east, the prairies of the Great Plains originally reached directly below the mountain flank. Almost all of them have been converted into agricultural land. In the park there are some small remnants on moraine ranges , where the high grass lawn communities merge into loose forest communities . They mainly consist of American quivering aspen and, like the prairies, are dependent on sporadic fires, which push back species that are less well adapted to the environmental factor fire . Yellow pine , Douglas fir , coastal pine and Engelmann spruce mix with the poplar stands . Since fire was fought in the national park until the 1980s, the yellow pines in particular have increased massively. Artificially placed, small fires in suitable times of the year are intended to restore the original condition.

In the west, the foothills of the Palouse area extend into the river valleys on the park boundary. The prairies here are thicker and form a small-scale mosaic of wetlands and ridges. The tree species are the same as in the east, with coastal pine and quaking aspen preferring the more humid and yellow pines the drier locations. A gallery forest of willow and western balsam poplar stands on the banks of the river .

The prairies are habitats for animals that are adapted to drought and intense temperature fluctuations. These include a variety of rodents, including the northern pocket rat ( Thomomys talpoides ) and the Columbia ground squirrel , which live mostly underground. Glacier National Park no longer features herd animals on the prairies. Forest edges of the lowlands are the preferred habitat for the silver badger . The prairie hare only lives on the east side . Coyote , wolf, and puma are the prairies' largest predators , but they are also found in all of the park's other ecosystems. The American black bear only occasionally comes to the lowlands , the grizzly seldom. The bird life is diverse and consists of people living in the reed fields along the waterways, fowl in the prairies proper, and several species of falcons , buzzards and the Hudson's harrier (to list more common birds of prey).

Submontane forests

Forest communities of the hill countries can only be found in the park in the south-west. Giant arborvitae and hemlock can be found in protected valleys with high rainfall . Since the two species reach an early crown closure, the forests are poor in undergrowth and only shade-tolerant plants such as the Pacific yew and moss colonize the ground. After forest fires, the West American larch grows on these sites as a pioneer species . The Great Fire of 1910 has meant that the species has since then, and to date, been more widespread in this part of the park than is believed for previous centuries.

Montane forests

The montane forests below 1,400 meters in the east and 1,500 meters above sea level in the west make up the largest part of the park area. They are dominated by the Douglas fir . In dry locations and those with only a small amount of humus , quivering poplars and balsam poplars as well as the paper birch mix among them. The forests are rich in flowering plants in the herb layer and in mushrooms , depending on the season.

The park's wooded slopes are the most diverse habitat. Here the smallest mammal in the park who live American pygmy shrew , various croissants, including the Western gray squirrel , raccoon , North American porcupines and Spruce grouse and ruffed grouse , the largest grouse . The snowshoe hare lives in the deeper forest areas and on the edge of the prairies. It is the preferred prey for the Canadian lynx , with the two species having a close predator-prey relationship and their population dynamics directly related. In summer and autumn the forests are breeding and habitat for migratory birds , which the winters in the Rocky Mountains could not withstand. These include several species of tyrant , the cedar waxwing and the Andean treecreeper . Two species of nuthatch are barnacles and only migrate short distances in winter depending on the weather. Nine species of woodpecker are regularly observed in the park, eight of which breed in the area.

In the forests of different elevations to live white-tailed deer , mule deer , elk and moose .

Subalpine forests

The tree line in Glacier National Park is around 2000 m. The Engelmann spruce dominates the forest , mixed with the rock mountain fir . The undergrowth consists mainly of berry bushes, including Rubus nutkanus .

Open locations at this altitude level arise in particular in avalanche stretches or through very thin layers of humus on rock heads. They are shaped by the bear grass , which was chosen as the symbol of Glacier National Park.

The rock mountain grouse inhabits the forests of middle and higher elevations. The badger is particularly noticeable because it uses exposed trees as a song observatory. Typical mammals are several martens, including the fishing marten and the spruce marten , as well as mouse weasels and ermines . The wolverine was almost wiped out in the park by being chased as harmful game ; its populations have recovered since the hunt ended.

The following Krummholz zone extends to around 2,300 meters, at exposed locations such as the large passes only around 100 meters lower. The character tree in the northern Rocky Mountains is the white-stemmed pine ( Pinus albicaulis ), alongside the rocky mountain fir, the Engelmann spruce and the flexible pine ( Pinus flexilis ). The rocky mountain larch , which turns its needles bright yellow relatively early, is rare but very noticeable in late summer and autumn .

The grizzly comes into the deeper forests in spring, but lives mainly in the high areas of the park, both in the loose forests and above the tree line. It feeds mainly on berries and roots, animal food only makes up a small part of its food spectrum. The pine jay is the character bird of the Krummholzzone, it feeds mainly on the seeds of the white-stemmed pine.

Alpine Zone

There are no trees above 2,300 meters. However, dwarf forms of several types of willow form a network only around 15 cm high in more humid locations, which creates a microclimate and holds heat and moisture, as well as humus and seeds. Herbaceous plants such as heather and clove root form extensive stands. Above 2,600 meters there is only a few humus soils, alpine lawn communities with flowering plants from the Jacob's ladders , columbines , sedum and buttercup families still grow here . Pure rock sites are overgrown with lichens . There is life even in snow fields: the so-called blood snow consists of snow algae , predominantly of the genus Chlamydomonas .

The only bird that can be found at these heights all year round is the white-tailed ptarmigan ( Lagopus leucura ). The ice gray marmot and the American pika ( Ochotona princeps ) as well as the mountain goat are mammals and are the exclusive inhabitants of the alpine zone. The bighorn sheep spends the summer above the tree lines, but retreats into the woods in winter.

Lakes and watercourses

22 species of fish live in the over 700 lakes, streams and rivers of the park. Six of these were introduced by humans: the Arctic char , which was originally only found in the northeast of the park, was introduced into the waters around the park and migrated up into the park area, so that it is now found in all of the lower-lying lakes. The lakes and river corridors through the park are habitat for bald eagles and ospreys . At Lake McDonald and McDonald Creek in the southwest of the park of the gathering in the autumn for spawning sockeye salmon hundreds of bald eagles. Other species of aquatic habitats include the Canadian beaver and the American otter . The long-tailed weasel also lives near the water .

history

Originally the area was settled by Indians . From the Paleo-Indian period , four cultures can be identified between 10,500 and almost 8,000 years before the present . The oldest finds come from the northeast of the park on the Belly River . These are projectile points from the Clovis culture , about 10,500 years BP. The Clovis people still lived under the influence of the last ice age , which was coming to an end (called Wisconsin glaciation in North America ) and were hunters and gatherers , their source of food was the hunt ice age megafauna . A rapid climate change can be demonstrated around 9,900 years BP. The mountains were partially ice-free and the people of the Lake Linnet culture were able to extract argillite as a material for high-quality stone tools in the high elevations of today's park. About 9,300 years ago the climate became drier and the first forerunners of the prairies emerged below the mountains. The short-lived Cody culture lived from the communal hunt for bison, their characteristic spearheads were long and narrow. The subsequent Red Rock Canyon culture developed fishing as an essential foodstuff in autumn, when the salmon and trout move to the upper reaches of the rivers. The people were very mobile and won high-quality chert in several places in today's national park and, depending on the season, hunted big game at all altitudes in the mountains. With it, the Paleo-Indian period came to an end about 7,750 years ago, the Archaic period began.

It lasted until around the year 500 and is characterized by multiple climate changes. The Indians adapted to the environmental conditions and the development of the flora and fauna. In part, there were also cultural differences between the east and west sides of the mountains. Around 6,000 BP, the Indians developed the Buffalo Jump hunting method , in which herds of bison were driven over the edges of terrain and fell to their death. With the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump , a World Heritage Site, and the First Peoples Buffalo Jump , two important jump sites are located within a radius of about 100 km from Glacier National Park. After the end of the archaic period, the non- ceramic in the Northern Plains to 900 were arrow and arc introduced. The Spaniards brought horses to America in the 16th century , which also spread to the northern prairies by the 17th and 18th centuries.

The first whites

When they first came into contact with whites, five peoples lived in the vicinity of today's national park. The Kutenai , Flathead and Kalispel in the west on the Flathead River , the Confederation of Blackfoot or the southern Piegan belonging to it in the east on the prairies and the Stoney with only a few hundred people in the eastern valleys of today's park around the Belly River . The peoples of the western flank migrated over the mountains to the east side to hunt buffalo in spring and autumn , where there were regular conflicts with the Blackfoot. The Blackfoot and the Flathead considered the mountains to be the "backbone of the world". They played an essential role in their creation myths .

Two fur traders from the UK's Hudson's Bay Company were the first Europeans to see the mountains in 1785 and 1792. On his way back from the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1806, Meriwether Lewis came near the mountains and reported in his notes of the mountain range that suddenly rose from the prairie and which now bears his name. In 1810 whites were first demonstrably in today's park area. They were hunters who supplied British and French-Canadian fur traders. In the 1830s and early 1840s, fur hunters penetrated into the mountains of today's national park and decimated the population of beavers . In addition, contact with the whites brought smallpox to the prairies. The greatest infection in 1837 spread to all prairie peoples; up to a third of the Indians died from it. Large-scale whites hunted bison herds on the northern prairies in the 1850s. The Blackfoot saw the very basis of their diet and culture threatened and often fought with the white invaders, so that they were soon considered the most feared people.

In 1851 the first reservation of the northern prairies was established, in 1855 the Blackfoot was assigned to the area north of the Missouri River and east of the main Rocky Mountains ridge. The reserves were subsequently unilaterally reduced several times by the US government, so much in 1872 that more than two thirds of the Blackfoot moved permanently to Canada.

Assignment of the mountains and protection

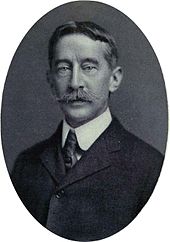

For the upper class on the American east coast, wilderness had taken on a romantic character. With the Yosemite Grant in 1864 and the world's first national park in Yellowstone in 1872, the United States created the first large-scale nature reserves that followed a romantic notion of majestic landscapes. Indian inhabitants of the landscapes disturbed the impression of untouchedness. George Bird Grinnell had come to the northern prairies as a government scientist in 1874, and when he first saw the Rocky Mountains of northern Montana in 1885 he was fascinated by the mountainous landscape. In the meantime editor of the magazine Forest and Stream and with good family and personal contacts in the ministries of Washington, he was an influential propagandist for the protection of the mountains. But he also came into close contact with the Blackfoot and was very committed to compliance with the contracts with them, the timely delivery of food and other services.

In the late 1880s there were rumors of abundant mineral deposits in the mountains. Hundreds of prospectors broke into the reservation on their own, partly encouraged by the agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs , who hoped that mining would also help the Indians in the reservation or were simply corrupt . Under pressure, the Blackfoot ceded the mountainous portion of their reservation in 1895 in exchange for a $ 1.5 million trust and cattle and other food supplies. You were guaranteed the continued use of the ceded area ( ceded stripe ) as long as the area remained “ public lands of the United States” . In addition to being a food reservoir after the bison was eradicated, the mountains had also become important as a supplier of wood, as the Indians settled in their reservations and built log houses . They also served as a refuge for religious ceremonies that had been banned since the 1880s.

At Blackfoot's request, Grinnell was involved in negotiating the treaty as a government representative. Because of his knowledge of the mountains, he did not believe in abundant mineral finds and was already campaigning for a nature reserve. On the western flank of the ridge, the later founder of the US Forest Service , Gifford Pinchot , nature philosopher and conservationist John Muir and others were in the process of designating a forest reserve. In 1896, Grinnell lobbied to protect the mountains in the east that had been ceded by the Blackfoot. In February 1897, President Grover Cleveland established the Lewis and Clark Forest Reserve , which encompassed the entire area of the later national park and adjacent areas to the south. Grinnell was already thinking of a national park .

Meanwhile, the area had become more accessible to visitors. As early as 1853 a possible northern route for the transcontinental railroad had been explored under the direction of Isaac Stevens . The scouts did not find Marias Pass until the following year , which the Indians had recommended to them as a route across the continental divide without major inclines. However, the route of the first transcontinental railway line took place over the Great Salt Lake around 500 km further south. It was not until 1889 that the Great Northern Railway re- explored a route via Montana and, from 1891, ran its route from Minneapolis / St. Paul in Minnesota in the far north of the United States at Marias Pass over the continental divide to Seattle , which was reached in 1893. The route of the railway was to form the southern border of the national park when it was later placed under protection.

The railway company and its president James J. Hill became a supporter of Grinnell in the designation of the reserve. In Yellowstone National Park the railway connection had increased the number of visitors tenfold in ten years and the Great Northern Railway hoped to increase the utilization of the railway with a national park on its route by tourists. The lobbying work of Grinnell and Hill was successful, in May 1910 the United States Congress passed the "Act Establishing 'Glacier National Park' in the Rocky Mountains South of the International Boundary in the State of Montana and for Other Purposes (36 Stat 354)" .

According to the official opinion of the US federal government, the area ceded by the Blackfoot was dedicated to a specific purpose with the establishment of the Forest Reserve , but no later than the National Park , and was therefore no longer public land within the meaning of the Treaty of 1895. The Blackfoot insisted on their rights to hunt and gather plants in the eastern part of the park. Several trials took place by 1932 that resulted in the Blackfoot's defeat, but the hunt continued on a small scale. After the herd animals, which are popular with visitors, have been fed in winter since the park was established, the administration noted significant overgrazing in the park's valleys in the 1940s . In the 1950s, a superintendent wrote to the federal level of the National Park Service that the Indians had been poaching too little for several years to limit the damage caused by the elk herds. In connection with the reform of American Indian policy , the Blackfoot made claims again since the 1970s and 1980s. The National Park Service rejects this, but the Blackfoot Confederation assumes that their rights under the Treaty of 1895 will continue to exist de jure .

National park

The park is the tenth national park in the United States and was established as

"A public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people"

"Public park or amusement facility for the benefit and pleasure of the population."

Management of the park was transferred to the US Department of the Interior and in 1916 it was transferred to the newly established National Park Service . The administration had the task of "looking after the care, protection, administration and improvement as far as it is necessary with the preservation of the park in its natural state" and for "the care and protection of the fish and wild animals in the park" wear. In addition, it was allowed to provide areas of no more than 4 hectares per site for the construction of hotels and other accommodation for visitors, as well as small plots of no more than 4000 m² for summer houses. However, the received Bureau of Reclamation given the right, the rivers of the park for irrigation dam to be allowed.

developments

The National Park Service tried unsuccessfully to prevent a dam immediately east of the park boundary: The artificial Lake Sherburne extends about 6.5 km into the national park. A second, planned dam to enlarge the natural St. Mary Lake was stopped by protests by the park administration and politics. The Great Northern Railway used the authorization to build hotels and built three well-appointed hotels and two rustic chalets in different parts of the park from 1910 to 1915 . The hotels are located in easily accessible valleys on the east and west sides. The Granite Park Chalet is in the center of the park near Logan Pass and the Sperry Chalet is in the backcountry near Avalanche Creek. Other companies built other small hotels on the outskirts inside and outside the park boundaries. For the construction of the hotels and then for the tourists, access roads into the valleys and the first hiking trails were created at the expense of the hotel operators. In the first few years up to the founding of the National Park Service in 1916, the park administration had no significant funds available for the development.

In order to enable visitors to access the high mountains not only on foot or by horse, planning for the Going-to-the-Sun Road began in 1917 and it was built from 1921 to 1933 for around 2.5 million dollars. The almost 85 km long connection between the east and west sides of the park over the Logan Pass is still considered a masterpiece by planning engineer Frank Kittredge and landscape architect Thomas Chalmers Vint. The road blends into the landscape in a previously unknown way and engineering structures were built exclusively from the stone of the respective section and in a rustic style. Kittredge only rescheduled the route after the start of construction so that it took full advantage of the Garden Wall despite enormous additional costs and gained height with a slight incline, instead of impairing the slope significantly more with switchbacks. But only the guided tour over the Logan Pass made it possible to "demonstrate the magnificence of the park to the maximum". It is a National Historic Landmark regardless of the park's status . In the years that followed the Great Depression and the New Deal, several Civilian Conservation Corps camps brought unemployed young men to the park, where they built campsites and other tourist infrastructure as a job creation measure.

The task of protecting and caring for the fish and wild animals in the park was taken as an opportunity in the first decades to promote fishing fish and the popular animal species. " Predatory game " such as wolf , coyote , wolverine and puma were bitterly persecuted and almost exterminated even in the high areas. The pursuit of predators was recognized as problematic for the conservation goal of a national park in the 1920s, but it was not until 1928 that targeted hunting was largely ended and until the late 1930s that it was completely discontinued. The wolf was considered to be extinct around 1930, animals did not migrate into the park again from Canada until 1979 and are now forming a viable population again. In addition, popular, non-native fishing fish were used in all low-lying and some high-mountain lakes until 1971.

Since the 1970s, about 95 percent of the park area are away from the developed areas as de facto wilderness area managed a formal designation as wilderness reserve failed several times in Congress of reasons, have no effect on the actual management.

Forest fires were seen as a threat to nature until the 1980s and not as an environmental factor to which ecosystems are adapted. In 1935, 31 km² near the east entrance of the park was affected by a large forest fire. In an intensive debate about the value of undisturbed natural processes, the representatives of the forestry of that time prevailed and had the entire area cleared and leveled with heavy equipment. Reasons were the fear that the damaged forests would easily fall victim to a new fire and the unwillingness to expect the tourists in the most visited part of the park to see the traces of a large-scale forest fire. Parts of the area were reforested, others have since been subject to natural growth, but large areas of the area affected at the time are largely free of trees to this day.

Since 1931 Rotarians from Montana and Alberta had campaigned for Glacier National Park with the adjoining Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada, which had existed since 1895, to be designated as an International Peace Park . The governments agreed and in 1932 the first cross-border nature reserve was established with the aim of promoting and celebrating peace between peoples. Rotarians from the two states and international guests have come together annually in the park on the border since then. Both parks were designated independently by UNESCO as biosphere reserves and jointly declared a World Heritage Site in 1995 .

An extensive educational program has existed in the park since 2002 under the name Crown of the Continent Research Learning Center . The park administration scientists work closely with universities and other institutions. For the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the national park in 2010, there has been a program of scientific conferences, an art project and special offers for visitors to the park and residents of the neighboring settlement areas since the end of 2008.

Protective measures and natural influences

Due to the almost original condition of the park, only a few special protective measures are required. Around 125 species of neophytes are known and observed. In some parts of the park - especially in the valleys - they are fought with mechanical means. A multi-year research program on the expansion of the introduced fish species has been running since 2007, which is to lead to a management plan in which lakes active measures to restore the original fish fauna are suitable and necessary. One of the first implementations is a fish-impermeable barrier in Quartz Creek , which will keep alien fish below from migrating to stretches of river and lakes above the barrier that are only native to native species.

The white-stemmed pine ( Pinus albicaulis ) has been severely restricted in its vitality by the rust fungus Cronartium ribicola throughout the Pacific Northwest and the northern Rocky Mountains since the 1930s . While 55 percent of all trees of the species in the national park were infested in the 1990s, around 50 percent have now died and 75 percent of the living trees are infected. In addition, all pines, especially the yellow pine , are attacked by the mountain pine beetle. Relationships between the rapid spread of infections and the mass infestation by the bark beetle with climate change are considered likely. The park administration is experimenting with the cultivation of genetically resistant specimens of the affected tree species and afforestation with their offspring.

Forest fires play a special role in the park's ecosystems . Every year there are minor fires due to natural causes, especially lightning . They are from the disturbance ecology regarded as an environmental factor that produced the open areas in a previously closed forest and the succession on land Klimaxstadium can set in motion again. The plant species are adapted to periodic forest fires and can reproduce again after a fire. Because forest fires have been suppressed with massive interventions for several decades since the park was placed under protection, an unusually large amount of fuel has accumulated in the forests of the national park. After a particularly dry spring, the most extensive fires in the park's history broke out in the summer of 2003. Around ten percent of the park area was affected, and there were large fires, especially in the east of the park and in the center of the park on the section of Park Street called The Loop . In the 20th century, fires in 1910 ( Great Fire of 1910 ), 1935, and 1967 were unusually large.

Global warming hazard

Global warming is considered to be the factor that contributed to the particular extent of the forest fires in 2003 . Because of its isolation from technical influences and the existence of data from around a century, the Glacier National Park is the central research area of the American geological service United States Geological Survey for the program Climate Change in Mountain Ecosystems ("Climate Change in Alpine Ecosystems"). In particular, the extent and other data of the glaciers in the park are collected.

The number and size of the glaciers in the national park have decreased significantly in the wake of global glacier melt . At the end of the 19th century there were 150 glaciers with more than 25 hectares, in 2019 there were only 25, whose melting is also expected in the future. Scientists estimate that by 2030 the last glacier in the national park will have disappeared. The extent of each glacier has been mapped for decades by the National Park Service and the US Geological Survey. By comparing photographs from the mid-19th century with current images, there is ample evidence that the national park's glaciers have receded significantly since 1850. In 1850 there were around 150 glaciers in the area of today's park, and the larger glaciers now take up about a third of the area they occupied in 1850 at the time of their first investigation and the local climax of the Little Ice Age . A large number of smaller glaciers have completely melted. In 1993 the glaciers of the national park only covered an area of almost 27 square kilometers. In 1850 it was still about 99 km². It is certain that the park's glaciers will be completely melted by 2030. A reinterpretation of the data in 2009 suggested that the glaciers would disappear by 2020.

Climate change is not only associated with the disappearance of glaciers, with consequences for the water regime of streams and lakes, it is also expected that the boundaries of the climatic zones in the mountains will move upwards.

tourism

Tourism in Glacier National Park was largely determined by the Great Northern Railroad in the early years . It competed with the Canadian Pacific Railway , which expanded Banff National Park north in Alberta, Canada, and with the Northern Pacific Railway , which promoted tourism in Yellowstone National Park further south. They all tried to get visitors to the parks to use their railroad lines. James J. Hill, President of the Great Northern Railroad, relied on the network of his hotels and chalets. From 1925 there was a licensed partner of the park administration who, with a thousand horses, brought over 10,000 visitors annually from one of the valley hotels to the high elevations of the park and to one of the chalets and the next day over the mountains to one of the other valleys - and the hotel there .

Facilities

But the future of tourist development belonged to the car. Stephen T. Mather , the founding director of the National Park Service established in 1916, relied on the development of the parks and commissioned the Going-to-the-Sun Road. But he also recognized that the traffic and the buildings in the parks should not destroy what the tourists were looking for, so in 1924 he rode up into the mountains himself to explore the route. When the road was opened in 1933, his successor Horace Albright put this into the words: “Most of Glacier Park will only ever be accessible on paths [...] Let us not allow other roads to compete with the Going-to-the-Sun [Road] . It should be unchallenged and unique. "

Going-to-the-Sun Road is the main attraction of Glacier National Park today. About 80 percent of all park visitors drive the pass road. Visitors can experience the high mountains on it, at the Logan Pass there is a visitor center with an exhibition on the natural history of the region and short and long hiking trails branch off from the road in many places. Because of the long, hard winter in the high mountains, it is only open from early June to mid-October. From 2006 to 2012 the street was rehabilitated in sections, always remaining open to traffic. Other roads in the park are the International Chief Mountain Highway to Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada and several spur roads to the developed valleys on the east side.

There is a system of shuttle buses that take hikers to and from the trails so they don't just have to walk circular trails, and red tour buses called “Jammer” have been running in Glacier National Park since the 1930s. They are still the original White Motor Company vehicles . They were completely overhauled several times and, shortly after the turn of the millennium, converted to a drive with LPG to become more environmentally friendly. Excursion boats and ferries operate on the large lakes of the park. Two boats from the 1920s are still in use on Swiftcurrent Lake and Two Medicine Lake. There are over 1,100 kilometers of hiking trails in the park, ranging from short paved paths to wilderness tours lasting several days. The 5,000-kilometer Continental Divide Trail , which runs along the continental divide to the border with Mexico, begins in the park at the Canadian border . Most of the trails are also suitable for riders. Both short rides and tours lasting several days are offered. There are also some routes that are approved for mountain bikes .

Visitors

The economic importance of the park for the tourism industry in Montana is high. Around 80 percent of foreign park visitors come to Montana specifically for the park, and tourists who visit Montana for the outdoors stay longer and spend more money in the state than all other visitors.

In 2009 over two million park visitors came. Most of them stayed outside the park. Almost 380,000 overnight stays were counted in the park. Of these, around 130,000 stayed in the hotels and motels, 101,000 stayed in tents on the campsites and around 106,000 in their own mobile homes. The vast majority of tourists stayed on the streets and in their immediate vicinity or made short hikes from the valley locations, visitor centers or the stops of the shuttle buses. After registering as a backcountry permit , individuals and groups spent a total of 40,855 nights on multi-day tours in the undeveloped hinterland. The visitors concentrated on the months of July and August.

Before 2001, the border could be crossed on foot at any point if the traveler reported immediately to one of several checkpoints and met the requirements for visa-free entry into the USA or Canada. As a result of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 , these possibilities were greatly reduced. The border can only be crossed on foot at the Goat Haunt Point of Entry . An excursion boat runs there on the cross-border Upper Waterton Lake, which brings visitors from Canada to the American side. Canadians, US citizens, and permanent residents need a passport. Citizens of other countries are allowed to take part in the boat tour, but only leave the immediate vicinity of the landing stage if they have already entered the USA at the official border crossing and the duration of stay granted to them is still running. Otherwise, the two parts of the International Peace Park are only connected for you by the road network outside the parks.

literature

- Tony Prato, Dan Fagre (Eds.): Sustaining Rocky Mountain Landscapes - Science, Policy, and Management for the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem . Resources for the Future, Washington DC, 2007, ISBN 978-1-933115-45-0

- Richard West Sellars: Preserving Nature in the National Parks . Yale University Press, New Haven, CT and London, 1997, ISBN 0-300-06931-6

- Kathleen E. Ahlenslager: Glacier . KC Publications, Las Vegas, 1988, ISBN 0-88714-018-1

Web links

- National Park Service: Glacier National Park (official site; English)

- United States Geological Survey: Glacier National Park Research

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

Individual evidence

- ^ NPS Glacier National Park: General Information (accessed March 8, 2009)

- ↑ Ben Long: The Crown of the Continent Ecosystem . In: Tony Prato, Dan Fagre (eds.), P. 23

- ^ Top Ten Montana Weather Events of the 20th Century , NOAA, accessed March 8, 2009

- ↑ This chapter is based on: Trista Thornberry-Ehrlich: Glacier National Park - Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Natural Resource Report NPS / NRPC / GRD / NRR — 2004/001 . National Park Service, Denver, Colorado, 2004, pp. 16 ff., 33 ff. (Also online: Geologic resource report ; PDF; 2.2 MB)

- ^ Glacier National Park Geology , National Park Service, accessed March 11, 2009

- ↑ Geology fieldnotes - Glacier National Park , National Park Service, accessed December 18, 2009

- ↑ National Park Service: Glacier National Park Fossils (accessed March 11, 2009)

- ↑ Mikhail A. Fedonkin, Ellis L. Yochelson: Middle Proterozoic (1.5 Ga) Horodyskia moniliformis - the Oldest Known Tissue-Grade Colonial Eucaryote . In: Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology , Volume 94

- ^ Glacier National Park: Mammal Checklist

- ↑ Michael Quinn, Len Broberg: Conserving Biodiversity . In: Tony Prato, Dan Fagre (Eds.), P. 103 and Glacier National Park: Mammal Checklist

- ↑ a b Sellars, p. 80

- ^ Glacier National Park Fish , National Park Service, accessed March 14, 2009

- ↑ National Park Service: Glacier National Park Environmental Factors (accessed March 26, 2009)

- ↑ Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Rule To Identify the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment and To Revise the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife , Federal Register (PDF; 908 kB)

- ^ Judge Orders Protection for Wolves in 2 States , New York Times, August 5, 2010

- ^ Glacier National Park Plants , National Park Service, accessed March 26, 2009

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the descriptions of the plant communities are based on Ahlenslager, Chapter A Mixing of Floras , pp. 20–31 with further evidence, the animal world on the commented species lists of the park administration under Glacier National Park: Natural Resources and Glacier National Park: Animals . Additional information comes from Ben Long: The Crown of the Continent Ecosystem . In: Tony Prato, Dan Fagre (eds.), P. 23 ff

- ^ Glacier National Park Wildland Fire Management , Glacier National Park, accessed March 14, 2009

- ↑ Ahlensberger, p. 36

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the prehistory is based on Brian OK Reeves: Native Peoples and Archeology of Waterton Glacier International Peace Park . In: Tony Prato, Dan Fagre (Eds.), Pp. 39-54

- ↑ Mark David Spence: Crown of the Continent, Backbone of the World - The American Wilderness Ideal and Blackfeet Exclusion from Glacier National Park . In: Environmental History , Vol. 1, No. 3 (July 1996), p. 32

- ↑ The history of the 1895 treaty and protection is based on Mark David Spence: Crown of the Continent, Backbone of the World - The American Wilderness Ideal and Blackfeet Exclusion from Glacier National Park . In: Environmental History , Vol. 1, No. 3 (July 1996), pp. 29-49

- ↑ Yellowstone National Park's First 130 Years ( Memento of the original from April 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , National Park Service, accessed March 22, 2009

- ^ Mark David Spence: Dispossessing the wilderness . Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-19-514243-8 , pp. 96-100

- ↑ Law on the establishment of the "Glacier National Park" in the Rocky Mountains south of the international border line in the state of Montana and for other purposes (36 Stat 354)

- ^ Sellars, p. 65

- ^ Donald H. Robinson, Through the Years in Glacier National Park - An Administrative History . Glacier Natural History Association, 1960, chapter 3

- ^ Frank A. Kittredge: Trans-Mountain Highway, Glacier National Park, Report to National Park Service , February 5, 1925, 1-3, 9-10, 22. Glacier National Park, Central Files, Entry 6, RG 79, National Archives, Washington, DC Quoted in: Glacier National Park Going-to-the-Sun Road , accessed March 27, 2009

- ↑ see: List of National Historic Landmarks in Montana

- ↑ Sellars, p. 72 ff.

- ↑ Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks: Gray Wolf ( Memento from October 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Glacier Park seeks wilderness designation , The Missoulian, November 25, 2008, accessed April 26, 2010

- ↑ Sellars, p. 128 f.

- ↑ National Park Service: Science in the Crown Newsletter - Winter 2008, Vol. 4, No. 1 (accessed on March 26, 2009; PDF; 1.2 MB)

- ^ Fish passage barrier complete , National Park Service, September 24, 2012 press release

- ↑ USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center: Whitebark Pine Communities ( Memento of May 27, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed March 27, 2009)

- ↑ Resource Bulletin June 2006 , National Park Service Crown of the Continent Research Learning Center, accessed on March 27, 2009 (PDF; 208 kB)

- ^ Glacier National Park Fire Regime , National Park Service, accessed March 26, 2009

- ↑ US Glacier national park losing its glaciers with just 26 of 150 left . In: The Guardian , May 11, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ↑ a b Climate Change in the National Park - The Melting Glaciers of Montana. Retrieved on March 24, 2020 (German).

- ^ Myrna HP Hall, Daniel B. Fagre: Modeled Climate-Induced Glacier Change in Glacier National Park, 1850-2100 . In: BioScience Vol. 53 No. 2 (February 2003), pp. 131–140 (also online: Glacier Change in Glacier National Park (PDF; 1.3 MB) )

- ↑ No more glaciers in Glacier National Park by 2020? , National Geographic Magazine, accessed March 26, 2009

- ↑ Ahlenslager, p. 46

- ↑ Horace M. Albright: Memorandum for the Secretary , re: Glacier ceremonies, July 17, 1933, Glacier National Park, General File, RG 48, National Archives, Washington, DC Quoted from: Glacier National Park Going-to-the-Sun Road (accessed March 27, 2009)

- ^ Glacier Park Boat Co .: Our historic wooden boats ( Memento from July 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Norma Nickerson: What the People think - Glacier National Park and Vicinity (PDF; 169 kB) . University of Montana, Institute for Tourism & Recreation Research, May 2003, p. 7 f .; Neal Christensen, Norma Nickerson: Three Communities Explore Tourism (PDF; 142 kB) . University of Montana, Institute for Tourism & Recreation Research, September 1996, p. 11

- ↑ Statistical Abstract: 2009 (PDF; 735 kB) Natural Resource Data Series NPS / NRPC / SSD / NRDS — 2010/039. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado, p. 20

- ^ Glacier National Park: Goat Haunt , National Park Service

- ^ Glacier National Park - Goat Haunt Trail Status , National Park Service