Mule deer

| Mule deer | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mule deer |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Odocoileus hemionus | ||||||||||||

| ( Rafinesque , 1817) |

The mule deer ( Odocoileus hemionus ) or large-eared deer is a deer widespread in western North America . He is the closest relative of the white-tailed deer . There are several subspecies that can be divided into two groups. Those west of the Rocky Mountains are mostly referred to as black-tailed deer. The species name mule deer refers to the large ears that are reminiscent of those of mules .

features

The males of the mule deer have a height at the withers of one meter and a head-trunk length of almost two meters. On average, the males weigh between 79 and 91 kilograms, and very large deer occasionally reach a weight of up to 204 kilograms. The heaviest stag weighed to date was shot in Colorado in 1938 and weighed 237 kilograms. The females weigh around a third less than the males. The ears reach a length of 28 and a width of 15 centimeters.

In the nominate form, the tail is white except for a tip of about 5 centimeters. In some of the subspecies, however, the tail is entirely black. The summer coat is reddish brown, the winter coat, which has thick gray woolen hair, is gray-brown.

Locomotion

For the mule deer, three gaits can be distinguished: walk, trot and gallop. Gradual pulling is the common mode of locomotion. Startled mule deer also show bouncing jumps . They push each other up with all four runs at the same time. This jump, which is also typical for a number of antelopes and is also shown by fallow deer, is very strenuous. However, it allows mule deer to jump up a steep slope very quickly and escape a predator. When galloping, mule deer reach a speed of almost 60 km / h.

distribution

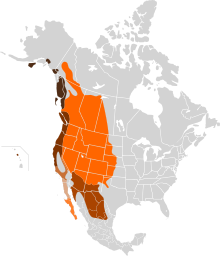

The mule deer lives primarily in the Rocky Mountains , but also in the coniferous forests of British Columbia , in the western prairies, and in the semi-deserts and deserts of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico . In most regions of its range, the mule deer stay in mountainous regions until snowfall forces them to move to lower altitudes. The autumn and spring migrations of this deer species can be up to 160 kilometers. On hikes, mule deer sometimes join together in larger herds.

Unlike the white-tailed deer , the mule deer is not a cultural follower and avoids the proximity of human settlements.

Subspecies

The mule deer can be divided into two subspecies, on the one hand that of the black-tailed deer, represented by the small sitka black- tailed deer ( O. h. Sitkensis ) and the Columbia black- tailed deer ( O. h. Columbianus ), and on the other hand into the actual mule deer in the narrow sense. The latter include the California mule deer ( O. h. Californicus ), the Rocky Mountain mule deer ( O. h. Hemionus ) and O. h. eremicus from the desert areas of the southwest. Black-tailed deer are significantly smaller than typical toll deer. The California mule deer is, in a sense, a transitional form between the black-tailed deer and the Rocky Mountain mule deer. South of the California mule deer live with O. h. fulginatus and O. h. peninsulae two other subspecies. The latter occurs only in the south of the Baja California peninsula . A small form, O. h. cerrosensis , also lives on the island of Cedros off the Mexican coast. Sometimes the mule deer are separated as a separate subspecies on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada. However, they are very similar to the California mule deer on the western slopes of the mountains, and so their status is questionable.

Way of life

Mule deer mainly eat grass, herbs, berries, fruits, twigs and the shoots of bushes and trees. They mostly graze early in the morning and late afternoon. Especially in the hotter regions of their range, they avoid activities during the hottest time of the day.

Males and females live in separate associations, older males occasionally also as solitary animals. The basic unit of the packs formed by females are mother families. In general, the mule deer lives in larger packs than the white-tailed deer. The cohesion of these groups is loose, and a strict hierarchy only develops during the mating season. The rutting season begins at the end of October, the peak of the rut falls in winter. During the rutting season, the males try to win the leadership of a group of female deer. Younger and weaker males that may already be present will be driven away. The size of the antlers often determines the success.

The gestation period is 210 days, mostly twins are rescued. The mule deer calves have spotted fur. During the first two to three weeks of their life, they do not follow the mother, but lie waiting in cover until the mother returns to suckle them. They lose the stain marks on their teenage dress around four months old. The close bond with the mother lasts for about a year. The female usually drives away the offspring that will follow her at a point in time shortly before the birth of this year's offspring.

In the regions in which the range of the mule deer overlaps with that of the white-tailed deer, there are occasional crossings of these two species. Mostly the mother animal is a mule doe. The males of the white-tailed deer prevail over the males of the mule deer in courting for a ruthless female because they are faster than mule deer and also much more persistent in pursuing the ruthless female. While the offspring are fertile, they have a higher mortality rate than the offspring of mule or white-tailed deer. They neither show such pronounced bouncing jumps as pure mule deer, nor do they reach the escape speed and endurance of white-tailed deer and are therefore more likely to fall prey to predators.

Predators and life expectancy

The oldest known mule deer to date was a hind in British Columbia, who reached the age of 22 years. The predators of the mule deer include feral dogs, coyotes, wolves, Canadian lynx and bobcat, puma and bears. The puma is probably the mule deer's main predator.

Threat and protection

Of the 10 million mule deer originally living in North America, populations had declined to 300,000 by 1900 due to excessive hunting. Thanks to effective protective measures, the numbers have risen to 5 million, but have stagnated since the 1960s. Chronic wasting disease , an infectious disease of the central nervous system in deer, has been documented since the late 1960s . The increasing numbers of white-tailed deer also pose a threat. On the one hand, this occurs through cross-breeding with white-tailed deer. White-tailed deer also transmit a parasite to mule deer that weakens the species more than the white-tailed deer.

The subspecies Odocoileus hemionus cerrosensis , the Cedros mule deer , is listed as threatened by the IUCN . It is restricted to the small Mexican island of Cedros off the coast of Baja California . The population is estimated at 300 animals.

Web links

- Odocoileus hemionus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2006. Posted by: Deer Specialist Group, 1996. Retrieved on 12 May, 2006.

literature

- Leonard Lee Rue III: The Encyclopedia of Deer . Voyageur Press, Stillwater 2003, ISBN 0-89658-590-5