Snowshoe hare

| Snowshoe hare | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Snowshoe hare ( Lepus americanus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Lepus americanus | ||||||||||||

| Erxleben , 1777 |

The snowshoe hare ( Lepus americanus ) is a species of the real hare in the rabbit family (Leporidae). It is distributed over much of northern North America in the United States and Canada . It is the smallest species in the genus and is generally described as rabbit-like rather than hare-like. It got its name because of the very large feet that are supposed to prevent sinking into the snow. The change of coat with a brown summer coat and a white winter coat is also typical for the species .

The species already described by the Göttingen veterinarian Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben in 1777 is considered to be the most original species of the genus. Within the distribution area, 15 subspecies of the snowshoe hare are distinguished.

features

general characteristics

The snowshoe hare is variable in terms of size and color within its large distribution area with numerous subspecies. He reaches a body length of 36 to 56 centimeters with a weight of 1.1 to 1.6 kilograms. Its tail length is 2.5 to 5.5 centimeters, the ear length 60 to 70 millimeters and the hind foot length 112 to 150 millimeters. It is the smallest species of the genus Lepus . In terms of its physique and its functional morphology, the snowshoe hare is more like a rabbit or a cottontail rabbit than a hare. The animals have a less pronounced sexual dimorphism , the females are on average somewhat larger and heavier than the males.

The back fur of the animals is brown, gray or reddish in summer, the belly side and the underside of the chin are white. Often the feet are also colored white. Like the mountain hare ( Lepus timidus ), the snowshoe hare also changes its coat color from brown to white in most populations, thus camouflaging itself from predators in the snow. When the coat changes, the undercoat retains its gray color, only the tips of the hair become white, so that the animals are white. The tips of the ears often remain black even in winter. With some subspecies in the southern areas, parts of the population remain brown even in winter. The coat change to winter coat takes place in August to November, that to summer coat in March to June.

The soles of the feet are densely hairy, especially on the hind paws, which gives it the snowshoe- like appearance. They result in the traces typical of the animals.

Skull and skeleton

| 2 | · | 0 | · | 3 | · | 3 | = 28 |

| 1 | · | 0 | · | 2 | · | 3 |

The skull and teeth have very distinctive features, including the ever-growing incisors . Like all hare-like animals, they have two incisors per half in the upper jaw , one of which is a incisor tooth and the other a pin tooth directly behind the incisor tooth. In the lower jaw there is only a single incisor designed as a incisor tooth. A typical tooth gap ( diastema ) follows the incisors . There are three premolars in the upper jaw, two in each of the lower jaw and three molars in both the lower and upper jaw . In total, the animals have a set of 28 teeth.

The main feature of the skull is that the supra-orbital legs back not with the frontal bones are fused, but break out, while the intermediate parietal bone with the parietal bone is fused.

genetics

The karyotype of the snowshoe hare consists of a chromosome set of 2n = 48 chromosomes, which is the originally recognized set of chromosomes within the real hare. It comprises eight pairs of metacentric (→ chromosome # components ) and submetacentric and 15 pairs of subtelocentric and acrocentric autosomes . The X chromosome is medium in size and submetacentric, while the Y chromosome is very small and acrocentric.

distribution

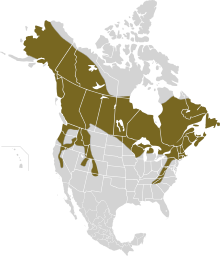

The snowshoe hare lives in North America . It occurs in almost all of Canada except the far north and in all provinces except Nunavut . In the United States, it is represented in Alaska and in the western states of Oregon , Washington , Nevada , Idaho , Montana , Wyoming , North and South Dakota and Colorado, as well as in individual regions of the highlands in New Mexico , Utah and California . In addition, the species is common in the Great Lakes region and the eastern states of Pennsylvania , New York , Maine , Vermont , Rhode Island , Wisconsin , Michigan , Minnesota , Massachusetts , Connecticut and New Hampshire . Historically, the snowshoe hare was likely found in the mountainous regions of West Virginia , North Carolina , Tennessee, and Virginia , but these populations are no longer present.

Way of life

The snowshoe hares are nocturnal and spend the day hiding in the vegetation. They are bound to the boreal mixed deciduous forest of North America with dense undergrowth. They occur in different forest regions with conifers, ash, birch, beech, maple and other trees. The animals need relatively dense ground and shrub vegetation that they can use as cover. Typically, successional forests and young forest stands between the ages of 25 and 40 are ideal. They prefer habitats on the edges of forests and clearings as well as swamp borders, but avoid open areas. The animals can be very common in areas where the undergrowth grows again after a fire, while they are rare in old forests with tall trees and little undergrowth. The animals are usually not found in small patches of forest and relic forests in agricultural areas.

Due to its white winter fur, this species needs a blanket of snow in winter. Two subspecies along the Pacific coast do not turn white in winter and can accordingly be found in forests with little or no snow cover. The snowshoe hare also seems to prefer the marginal habitat.

nutrition

As with other rabbits, the diet is vegetarian and in summer mainly consists of grasses , herbs, flowers, sedges and ferns . In winter they also gnaw on the soft bark of spruce, willow, birch or pine.

Especially in winter, the animals can occasionally eat the carrion of dead animals. After a study in Yukon , in which the carcasses of various animals were laid out, it was observed that snowshoe hares ate the meat of these animals, including that of other snowshoe hares or dead lynx, as well as the feathers of the grouse ( Falcipennis canadensis ). Carrion is probably a supplement for the animals when there is a lack of nutrients, especially in winter.

Reproduction and development

The breeding season of the snowshoe hares extends from March to September and is mainly regulated by the length of the light day (photoperiodic control). The beginning can also be strongly influenced by the weather and the current population density of the hares and can be postponed up to several weeks. In Alberta, the transition from winter to early spring with decreasing snow cover and the first higher temperatures of the year was identified as the earliest start of the breeding season.

The animals are generally promiscuous and mate with multiple sexual partners. The gestation period is about 36 days and the females produce an average of two litters per year in the northern parts of the distribution area and in the high areas or three to four litters in the southern distribution areas and in the lowlands. The litter size varies depending on the location and the number of previously produced litters. The females give birth to 2 to 6 young animals, whereby they usually have one more young animal in later litters than in the first litters of the year. This means that the females have an average of between 7 and 18 young animals per year.

The young are born with fur. After about two days they start hopping in the nest and after about five days they start digging. They gather in the nest about an hour or two after sunset and wait for the mother. As soon as it comes into the nest, it will suckle you for about five minutes. After six to eight days, the young begin to eat solid food.

Ecological networking

The population dynamics of the snowshoe hares and the Canadian lynx ( Lynx canadensis ) is considered a classic example of the predator-prey relationship . The species show a cycle in their population development over the common distribution area from Alaska to Newfoundland of about ten years length (actually observed: 9-11 years). It is generally assumed that these cycles are directly linked, since the snowshoe hare is one of the lynx's main prey animals. Within the food web , however, the relationships are more complex and the snowshoe hare is a key species within the North American ecosystem . The hares feed on various plants and, besides the lynx, there are other predators that prey on the snowshoe hare; The populations of the snowshoe hare are thus regulated by both the availability of food and the predatory pressure from various predators, while the populations of the lynx are largely directly dependent on the hare populations, which are their main food.

There are various mortality studies for the species in which various predators have been identified. In a study in Alaska, the predator pressure in the early succession forest was compared with that in the black spruce forest. If the predator source could be determined, hares in the early successional forest were 30% more likely to be killed by goshawks ( Accipiter gentilis ) than by other predators, and in the black spruce forest, Canadian lynxes were 31% more likely to be killed than by other predators. Great horned owls ( Bubo virginianus ) and coyotes ( Canis latrans ) represented smaller proportions of rabbit predators in both habitats and other causes of death were a very rare cause of death at 3%. Survival was highest in July and generally in summer as the predators had more alternative prey. Low survival rates coincided with the period of fur change, litters in spring and the young animals leaving the nests in autumn.

Systematics

The snowshoe hare is classified as an independent species within the genus of the real hare ( Lepus ). The species was scientifically described in 1777 by the natural scientist Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben , the founder of the Veterinary Institute of the Georg-August University in Göttingen , who already referred to it as Lepus americanus and thus classified it in the genus Lepus established by Carl von Linné . Erxleben described the type from "America boreeli, ad fretum Hudsonis copiossimus", the type locality was defined in 1909 by Edward William Nelson on Fort Severn in Ontario , Canada.

The species is clearly demarcated from other rabbit species and there are no hybrids with other species. Phylogenetic studies suggest that the snowshoe hare is the most original species of the genus and is therefore to be regarded as a sister species of the entire genus. It is therefore also assumed that the genus originated in North America, where the species spread from north to south and to Eurasia .

Within the species, the nominate form currently distinguishes 15 subspecies:

- Lepus americanus americanus Erxleben , 1777: nominate form - Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Montana and North Dakota

- L. a. bairdii Hayden , 1869

- L. a. cascadensis Nelson , 1907 - British Columbia and Washington

- L. a. columbiensis Rhoads , 1895 - British Columbia, Alberta, and Washington

- L. a. dalli Merriam , 1900 - Mackenzie District, British Columbia, Alaska, Yukon

- L. a. klamathensis Merriam , 1899 - Oregon and California

- L. a. oregonus Orr , 1934 - Oregon

- L. a. pallidus Cowan , 1938 - British Columbia

- L. a. phaeonotus J. A. Allen , 1899 - Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota

- L. a. pineus Dalquest , 1942 - British Columbia, Idaho and Washington

- L. a. seclusus Baker & Hankins , 1950 - Wyoming

- L. a. struthopus Bangs , 1898 - Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Maine

- L. a. tahoensis Orr , 1933 - California, western Nevada

- L. a. virginianus Harlan , 1825 - Ontario, Quebec, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee

- L. a. washingtonii Baird , 1855 - British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon

On the islands of Kodiak Island south of Alaska and Anticosti in the Saint Lawrence Gulf , snowshoe hares were introduced in historical times, although the origin of the founder population and thus the specific subspecies are unknown.

Hazard and protection

The snowshoe hare is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) as not endangered ("Least concern"). The southern populations in particular can be exposed to excessive population loss and habitat loss due to habitat fragmentation.

The population density is more or less even in Canada and Alaska, but unevenly distributed in the neighboring United States. The populations in the boreal forest fluctuate in their stocks after a 10-year cycle, whereby their density can vary 100-fold over several years. Southern populations can be non-cyclical or fluctuate with reduced amplitude. The status of the southeastern populations is unclear, but the southern limit of range could decline northward due to habitat loss, the increase in predators, especially coyotes, and perhaps with climate change and the loss of snow in winter.

Effects of global warming

Some studies attempted to model the effects of global warming on the ranges and populations of snowshoe hares and other rabbit species. While some studies assume that the distribution areas of the animals in the polar regions will shift towards the North Pole , others assume that the distribution areas will hardly change or not at all.

A study in Pennsylvania compared the winter behavior and heat production of snowshoe hares on the southern edge of their range in Pennsylvania with a northern population in the Yukon to investigate how these hares might react to changing environmental conditions. The animals from Pennsylvania have shorter, less dense and less white winter coats than their northern counterparts, which indicates less fur insulation. They also have lower fur temperatures, which shows that they produce less heat than animals in northern populations. In addition, the hares in Pennsylvania do not choose roosts that offer thermal benefits, but rather those that provide visual protection from predators. The results suggest that snowshoe hares may be able to adapt to future climatic conditions through slight changes in trunk properties, metabolism, and behavior, and that little or no effect on the limit of distribution is to be expected. On the other hand, a study in Washington State found that although both forest and snowpack contributed to the historical limit of distribution, the length of the snowpack in particular explains the recent shifts in the limit of distribution to the north, while forest cover has lost relative importance. According to the scientists, the loss and fragmentation of forest habitats have historically posed the greater threat to the animals of the southern range, while climate change has now become the greatest threat to the snowshoe hare.

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Snowshoe Hare. In: SC Schai-Braun, K. Hackländer: Family Leporidae (Hares and Rabbits) In: Don E. Wilson, TE Lacher, Jr., Russell A. Mittermeier (editor): Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Lagomorphs and Rodents 1. (HMW, Volume 6) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2016; P. 135. ISBN 978-84-941892-3-4 .

- ^ Brian Kraatz, Emma Sherratt: Evolutionary morphology of the rabbit skull. PeerJ 4, September 22, 2016; e2453. doi : 10.7717 / peerj.2453 .

- ↑ a b c Lepus americanus - Snowshoe Hare, description in the Vertebrate Collection of the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point ; accessed on February 19, 2019.

- ^ TJ Robinson, FFB Elder, JA Chapman: Karyotypic conservatism in the genus Lepus (order Lagomorpha). Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology 25 (5), 1983; Pp. 540-544. doi : 10.1139 / g83-081 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Lepus americanus in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018.2. Listed by: D. Murray, AT Smith, AT, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ↑ Michael JL Peers, Yasmine N. Majchrzak, Sean M. Konkolics, Rudy Boonstra, Stan Boutin: Scavenging By Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus) In Yukon, Canada. Northwestern Naturalist 99 (3), 2018; Pp. 232-235. doi : 10.1898 / NWN18-05.1 .

- ↑ Nils Chr. Stenseth, Wilhelm Falck, Ottar N. Bjørnstad and Charles J. Krebs: Population regulation in snowshoe hare and Canadian lynx: Asymmetric food web configurations between hare and lynx . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94 (10), 1997; Pp. 5147-5152. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.94.10.5147 .

- ^ Dashiell Feierabend, Knut Kielland: Seasonal Effects of Habitat on Sources and Rates of Snowshoe Hare Predation in Alaskan Boreal Forests. PLoS ONE 10 (12) December 30, 2015; e0143543. doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0143543

- ^ A b Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben : Systema regni animalis per classes, ordines, genera, species, varietas cum synonymia et historia animalum. Classis I. Mammalia. Weygand, Leipzig 1977 .; Pp. 330–331 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ J. Melo-Ferreira, P. Boursot, M. Carneiro, PJ Esteves, L. Farelo, PC Alves: Recurrent Introgression of Mitochondrial DNA Among Hares (Lepus spp.) Revealed by Species-Tree Inference and Coalescent Simulations. Systematic Biology 61 (3), May 1, 2012; P. 367. doi : 10.1093 / sysbio / syr114 .

- ↑ Juan Pablo Ramírez-Silva, Francisco Xavier González-Cózat, Ella Vázquez-Domínguez, Fernando Alfredo Cervantes: Phylogenetic position of Mexican jackrabbits within the genus Lepus (Mammalia: Lagomorpha): a molecular perspective. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 81 (3), 2010; Pp. 721-731. ( Full text )

- ^ Katie Leach, Ruth Kelly, Alison Cameron, W. Ian Montgomery, Neil Reid: Expertly Validated Models and Phylogenetically-Controlled Analysis Suggests Responses to Climate Change Are Related to Species Traits in the Order Lagomorpha. PLoS ONE 10 (4) April 2015; : e0122267.15. doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0122267 .

- ↑ LC Gigliotti, DR Diefenbach, MJ Sheriff: Geographic variation in winter adaptations of snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus). Canadian Journal of Zoology 95 (8), 2017; Pp. 539-545. doi : 10.1139 / cjz-2016-0165 .

- ↑ Sean M. Sultaire, Jonathan N. Pauli, Karl J. Martin, Michael W. Meyer, Michael Notaro, Benjamin Zuckerberg: Climate change surpasses land-use change in the contracting range boundary of a winter-adapted mammal. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283, March 30, 2016. doi : 10.1098 / rspb.2015.3104 .

literature

- Snowshoe Hare. In: SC Schai-Braun, K. Hackländer: Family Leporidae (Hares and Rabbits) In: Don E. Wilson, TE Lacher, Jr., Russell A. Mittermeier (editor): Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Lagomorphs and Rodents 1. (HMW, Volume 6) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2016; P. 135. ISBN 978-84-941892-3-4 .

Web links

- Lepus americanus inthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018.2. Listed by: D. Murray, AT Smith, AT, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2019.