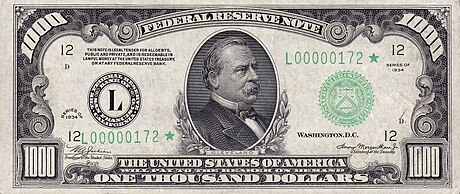

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (born March 18, 1837 in Caldwell , New Jersey , † June 24, 1908 in Princeton , New Jersey) was an American politician and the 22nd and 24th President of the United States . He held this office from March 4, 1885 to March 4, 1889 and again from March 4, 1893 to March 4, 1897. Cleveland was previously Sheriff of Erie County , Mayor of Buffalo from 1881 and Governor of New York State from 1882 .

Cleveland is the only president in United States history whose terms are not consecutive. Cleveland was the only Democratic member elected to the office of President in a 52-year era of Republican dominance from 1861 to 1913 ( Andrew Johnson was a Democrat but only came into office as succeeding Vice President for Abraham Lincoln ).

Life

Family and upbringing

Cleveland was born the fifth of nine children into modest living conditions. The son of a Presbyterian minister, he grew up in very authoritarian circumstances that gave him a very strong sense of duty. Until he was 17, he lived in Fayetteville and Clinton , two small towns in central New York where his father served as a pastor until his death.

Two of his brothers, Richard Cecil Cleveland (* 1835) and Lewis Frederick Cleveland (* 1841), died in the fire of the steamship "SS Missouri" on October 22, 1872 off the Bahamas.

Professional and political career up to the presidency

To support his family, Cleveland did not go to college but worked with an older brother in New York City . He then worked as an office worker in Buffalo , where he studied law in a law firm. He was admitted to the bar in 1858. During the American Civil War , he was assistant prosecutor for Erie County . In order to avoid military service, he put 300 dollars on a replacement, who took part for him in the war. His political opponents later accused him of this and called him a slacker . Nevertheless, at this time he gained a high reputation in court through great commitment and free speech. In 1870 Cleveland was elected sheriff of the county , held that office until 1873, and then returned to practice as a lawyer. In the next few years he achieved modest prosperity, which had a visible impact on his body size, which gave him his nickname Big Steve and which expanded to Uncle Jumbo as he grew larger . Cleveland led a rural life, uninterrupted by travel, determined more by hunting, fishing, and socializing with friends in poker saloons than by cultural interests.

Despite his previous sheriff's office, Cleveland had stayed away from party politics, which is why he was surprised when the Democrats nominated him for the mayoral election in Buffalo in 1881 , which he was able to clearly win thanks to his status as a newcomer. Already in the first twelve months in office he was able to achieve such successes against corruption and inefficiency in the city authorities as well as in the elimination of church tower and clientele politics that this made a lasting impression on the party leadership of the state. He was seen as a "veto mayor", that is, a mayor who often blocked decisions of the municipality with a veto. Cleveland used this means primarily to prevent the city from awarding expensive contracts. Taking advantage of Cleveland's image as an urban reformer, the Democrats successfully placed him in the 1882 election as governor of New York . As governor, he followed a policy similar to that of mayor and took action against the influential political clan Tammany Hall , even though it had supported his election. For Cleveland, for example, when filling offices and posts, qualification was decisive, not patronage of party friends. He vetoed laws that were too wasteful in Cleveland's eyes or promoted special privileges. In this way he prevented price reductions in public transport and working time regulations for those employed there. Cleveland's successes as a pragmatic reformer and political career changer led Democrats across the country to advertise him as a promising presidential candidate. At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1884, he was elected candidate for the presidential election in the second ballot with 683 of 820 votes cast . As his running mate for the vice-presidency was Thomas A. Hendricks nominated.

Presidential election of 1884

In the presidential election of 1884 , a Cleveland victory was expected to have a significantly different policy compared to its Republican predecessor Chester A. Arthur , especially with regard to the monopolies that were forming . However, he himself stated that even a change in government would not change the “existing conditions”. He had an advantage over the Republican candidate , James G. Blaine , in several ways. Through his crackdown on corruption and political clusters like Tammany Hall, for example, he had gained support from middle-class Republican and Democratic voters . His reforms, which emphasized hard work, efficiency and performance, also appealed to this group of voters. As governor, he also had a good chance of winning New York State , which is important for a majority in the Electoral College , since the traditionally democratic Solid South alone was not sufficient for this. Blaine also had a tough time with the Republicans; In particular, the Mugwumps faction , which sought reforms and wanted to eradicate corruption in politics and business, sympathized with the democrat Cleveland , who was considered to be of moral integrity .

During the election campaign, Cleveland campaigned for honest and efficient governance and the need for federal regulation (corrective action). Blaine, however, relied on an increase in protective tariffs and more government restraint ("constructive action"). The Democrats sought to portray him as a politically immoral advocate of big finance whose influence as speaker of the United States House of Representatives on railroad companies had paid off for him in the 1870s. Cleveland gave only two speeches during the campaign, in which he portrayed Republicans as corrupt and unrestrained public officials who are subservient to the interests of the rich. When it became known that Cleveland might have had an illegitimate child with Maria C. Halpin since the early 1870s, this was picked up by the Republican press and addressed in a popular cartoon. Initially, Cleveland did not take a stand itself, but left it to its closest confidants. He admitted having had a sexual relationship with Halpin in 1874. Though others, including his partner in the law firm, were considered fathers, he'd agreed to name the boy Oscar Folsom Cleveland without officially legitimizing him. After his mother became mentally ill, Oscar was adopted with Cleveland's support. Cleveland never saw either of them again.

The election campaign of 1884, which was primarily fought over the moral integrity of the two candidates, is considered to be one of the dirtiest in American history. In the end, Cleveland won the presidential election with a popular vote of 48.5 percent and 219 voters, just over Blaine, who came up with 48.2 percent and 182 voters. In New York, he received just 1,200 more votes than Blaine. Had it gone differently in that state, Blaine would have become president.

President of the United States

First term (1885–1889)

Cleveland took office on March 4, 1885, when he was sworn in in a ceremony outside the Capitol . He was the first Democratic President since the American Civil War and ended 24 years of Republican rule over the White House . He was the only president to date to give the inauguration speech in free speech. The hope of many Democrats for patronage in the allocation of posts for the new administration under the Spoils System disappointed Cleveland, as he continued to orientate himself on the principle of openness and efficiency. He dutifully adhered to the Pendleton Act , which required a non-partisan commission to select candidates for public service positions. Overall, however, he preferred deserving Democrats and, under the Tenure of Office Act, gave Republican federal employees leave to reassign their posts. The view of the Republicans that the law required the approval of Congress for these impeachments was successfully countered by Cleveland. With public support, he obtained a repeal of the Tenure of Office Act by Congress in 1887. Cleveland did not see itself as an activist president and developed few legislative initiatives, but tried to increase the efficiency of the federal administration through targeted personnel selection. When putting together the cabinet , he made decisions based on qualifications and, in accordance with his management style, delegated decision-making responsibility to the ministers, which he mainly used as an adviser.

With a few exceptions, Cleveland played a subordinate role in the laws that the United States Congress passed during its first term in office. She limited herself to taking public opinion for the project and accepting the laws through his signature . The Interstate Commerce Act 1887 created a federal agency to regulate rail traffic. It was the first independent federal agency . The Presidential Succession Act of 1886 was a new act of succession to the President, replacing the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives with members of the Cabinet. The last change to this law was in 1792. The Dawes Act of 1887 granted Indians parceled land ownership and citizenship when they were ready for a sedentary and "civilized" life. The Hatch Act of 1887 subsidized the creation of agricultural experimental stations at relevant university research institutes.

More significant for the assessment of the Cleveland presidency, however, are the legislative proposals that he prevented with his veto. He exercised this right more often than any previous president. He blocked 228 bills regulating the retirement benefits of American Civil War veterans alone. In this regard, Cleveland feared disproportionate increases in costs for the federal government and encouraging fraud and insincerity among those entitled. Since he occasionally included constructive criticism in his reasons for veto mockery, he irritated Congress and angered the veterans organizations. In 1887 he appealed against federal disaster relief for drought-hit farmers in Texas . In his view, support of this kind was not a federal competence.

Cleveland's two legislative initiatives were unsuccessful. Cleveland rejected the Bland – Allison Act of 1878, which provided for a move away from the gold standard and controlled bimetallism , i.e. the minting of silver coins. He feared that this increase in the money supply would result in a loss of confidence in the US dollar on the part of the creditors, which he found himself in contrast to the majority of his electorate. However, when Cleveland wanted to lower protective tariffs, the Democrats stood behind him. Due to ineffective leadership and poorly presented proposals, Cleveland was unable to repeal the Bland – Allison Act, nor to enforce significant changes in tariffs in its favor.

It significantly expanded the number of civil servants and made the US administration more effective. In economic and social policy, Cleveland spoke out in favor of the gold standard and extensive reluctance by the state towards companies. During his first term in office, the Statue of Liberty was inaugurated in New York in 1886 . In terms of foreign policy, he turned against the planned annexation of Hawaii .

Cleveland was the only President to date to marry while serving in the White House. Previously, his sister Rose Cleveland had served as a first lady . On June 2, 1886, he married his wife, Frances Folsom , in the White House . In the following years, the couple had three daughters and two sons, of whom the daughter Esther was born as the only presidential child in the White House to date.

Elections of 1888 and 1892

In the 1888 election, Cleveland ran for a second term. His Republican challenger was Benjamin Harrison . Although he won a majority in the popular vote (48.6 versus 47.8 percent), the result in the electoral committee led to a defeat in Cleveland. Since the states that Harrison won were mostly more populous and therefore had more electors, the result was 233 to 168. It was the second time in American history that a candidate had an absolute majority on the electoral body and thus became president despite him had fewer votes from the citizens than its opponent. Since then, this has happened again in 2000 and 2016 . As a result of the election Cleveland had to hand over the presidency to Harrison, who was sworn in on March 4, 1889.

The Democratic Party nominated Cleveland for the 1892 presidential election again as a candidate. Cleveland won the November 8, 1892 election against President Harrison. He secured 46 percent of the vote, for Harrison 43 percent of the voters spoke out. He also achieved a clear majority of 277 against 145 electors in the decisive electoral committee. Cleveland's running mate and second term vice president was Adlai Ewing Stevenson .

Second term (1893-1897)

After winning the election, Cleveland took the presidency for the second time. He is the only American president who has served two non-consecutive terms. Shortly before taking office, a panic broke out in the markets, which resulted in years of depression and high unemployment. Grover Cleveland was forced to work on the repeal of various laws that formed the basis for the dual currency of gold and silver coins even before taking office . He saw in this bimetalism the reason for the panic and the liquidity crisis of the federal treasury. To prevent the federal government from going bankrupt, he took on debt.

Shortly after taking up his second term in office, a cancerous ulcer on his hard palate had to be removed. The operation was kept secret so that there would be no doubt about his health and his manager. He was only able to partially realize his election promise to reform and lower import duties; and in recognition of the federal government's financial hardships, he had to approve the introduction of an inheritance tax and a progressive income tax later declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court, which later led to the adoption of the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution. During his second term, the 1894 congressional elections saw one of the largest power shifts ever; Republicans were able to win more than 100 seats in the House of Representatives , as Cleveland and the Bourbon Democrats were blamed for the depression, which the latter also lost control of the Democratic Party, which later nominated populist William Jennings Bryan for presidency.

He let the army crack down on the Pullman strike caused by wage cuts during the Depression .

After Grover Cleveland sought no further term in the presidential election in 1896 , he was replaced on March 4, 1897 by the Republican William McKinley .

In 1897 Cleveland was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society .

Cleveland suffered a heart attack in 1908 and died on June 24 of that year. He was buried in Princeton Cemetery in Princeton , New Jersey .

ideology

Cleveland promoted a Calvinist predestination ideology that gave the American nation a special role.

See also

literature

- Raimund Lammersdorf: Grover Cleveland (1885–1889): The growing importance of economy and finance. In: Christof Mauch (ed.): The American Presidents: 44 historical portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama. 6th, continued and updated edition. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-58742-9 , pp. 222–228.

- Raimund Lammersdorf: Grover Cleveland (1893-1897): The second term. In: Christof Mauch (ed.): The American Presidents: 44 historical portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama. 6th, continued and updated edition. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-58742-9 , pp. 239–244.

- Henry F. Graff: Grover Cleveland . The American Presidents Series: The 22nd and 24th President, 1885-1889 and 1893-1897. In: Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. , Sean Wilentz (Eds.): The American Presidents . 1st edition. Times Books, New York City 2002, ISBN 978-1-4299-9800-0 .

- Alyn Brodsky: Grover Cleveland: A Study in Character. St. Martin's Press, New York 2000, ISBN 0-3122-6883-1 .

- Richard E. Welch, Jr .: The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 1988, ISBN 0-700-60355-7 .

- Allan Nevins: Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage. Dodd, Mead & Company, New York 1933, LCCN 33-023946 .

Web links

- Cleveland at the National Governors Association (English)

- Biography on the archived website White House (English)

- American President: Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) . Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia (English, editor: Henry F. Graff).

- The American Presidency Project: Grover Cleveland. University of California, Santa Barbara database ofspeeches and other documents from all American presidents

- Life Portrait of Grover Cleveland on C-SPAN , August 13, 1999, 157 minutes (English-language documentation and discussion with historian Mark Wahlgren Summers and curatorial tour of the birthplace of Cleveland )

- Grover Cleveland in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Robert Kelley: Presbyterianism, Jacksonianism and Grover Cleveland . In: American Quarterly . tape 18 , no. 4 , 1966, ISSN 0003-0678 , pp. 615-636, p. 615 .

- ^ A b c d Henry F. Graff: Grover Cleveland: Life Before the Presidency . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 13 April 2018th

- ↑ https://books.google.de/books?id=UIbRHcz2ZysC&pg=PA80&lpg=PA80&dq

- ↑ http://www.sandisullivan.com/getperson.php?personID=I23992&tree=Tree

- ↑ http://www.sandisullivan.com/getperson.php?personID=I23995&tree=Tree

- ↑ a b Victoria Farrar – Myers: Cleveland, Grover (1837–1908) . In: Michael A. Genovese (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the American Presidency . 2nd Edition. Infobase Publishing, New York City 2010, ISBN 978-1-4381-2638-8 , pp. 94 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Henry F. Graff: Grover Cleveland . P. 53.

- ^ Howard Zinn: A People's History of the United States . Harper Perennial, New York 2005, ISBN 0-06-083865-5 , p. 258.

- ^ A b c Henry F. Graff: Grover Cleveland: Campaigns and Elections . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 13 April 2018th

- ^ HW Brands : American Colossus . 1st edition. Random House , New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-385-53358-4 , pp. 480 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c Victoria Farrar – Myers: Cleveland, Grover (1837-1908) . In: Michael A. Genovese (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the American Presidency . 2nd Edition. Infobase Publishing, New York City 2010, ISBN 978-1-4381-2638-8 , pp. 95 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Michael J. Korzi: Development of the Presidency, 1787-1945 . In: Richard A. Harris, Daniel J. Tichenor (Eds.): A History of the US Political System . Volume 1: Ideas, Interests, and Institutions . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2009, ISBN 978-1-85109-718-0 , Section 5: The Presidency, pp. 303 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b c Henry F. Graff: Grover Cleveland: Domestic Affairs . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 13 April 2018th

- ↑ Michele Landis Dauber: The real Third Rail of American Politics . In: Austin Sarat, Javier Lezaun (eds.): Catastrophe: Law, Politics, and the Humanitarian Impulse . University of Massachusetts Press, University of Massachusetts 2009, ISBN 978-1-55849-738-2 , chap. 2 , p. 67 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Member History: Grover Cleveland. American Philosophical Society, accessed June 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Graff, pp. 135-136; Nevins, pp. 762-764

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cleveland, Grover |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cleveland, Stephen Grover (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American politician, 22nd and 24th President of the USA (1885–1889 / 1893–1897) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 18, 1837 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Caldwell , New Jersey |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 24, 1908 |

| Place of death | Princeton , New Jersey |