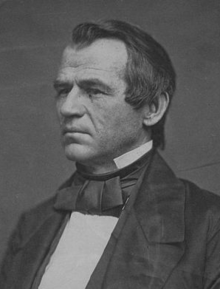

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (born December 29, 1808 in Raleigh , North Carolina , † July 31, 1875 in Carter Station , Tennessee ) was an American politician and the 17th President of the United States from 1865 to 1869 . As Abraham Lincoln's second vice president between March and April 1865, Johnson succeeded him after the fatal assassination attempt on the president . He was a member of the Democratic Party and the first US president to be impeached .

Coming from a poor background, Johnson enjoyed little regular schooling. First he worked as a tailor, later he began his political career as a small town mayor , member of the state legislature of Tennessee and a member of Congress . Johnson served as governor of Tennessee from 1853 to 1857 before serving in the US Senate for that state from 1857 to 1862 . During the American Civil War , President Lincoln made him Military Governor of Tennessee in 1862 . Since Johnson was the only politician from the southern states who opposed their secession during the Civil War , the Republican Lincoln nominated him before the presidential election in 1864 as his vice-presidential candidate for the National Union Party . After the election victory, Andrew Johnson took office as Vice President on March 4, 1865 .

As a result of Lincoln's assassination, Johnson himself had to take over the presidency. He was so in shock that he appeared drunk on his first public appearance afterwards. Johnson's years in the White House were marked by so-called reconstruction (the reintegration of the defeated southern states in the Civil War) and a reversal of Lincoln's policy of equal treatment for citizens of black and white skin. Johnson believed that whites were the "superior race" intellectually and morally. The question of whether the former Confederates should be fully admitted to the United States again under harsh or mild conditions created considerable political tension. Senators and MPs of the Republicans, who dominated the Congress , advocated severe punishment of the Southern leaders and full civil rights for the former African American slaves , which the president opposed because of his racist ideology. His stance towards the congress, especially with far-reaching rights for blacks, culminated in a narrowly failed impeachment procedure in early 1868. Hence, in the fall of 1868, Johnson had no chance of being re-elected. In March 1869 he was replaced by the Republican Ulysses S. Grant . In terms of foreign policy, however, he was able to record a success with the purchase of Alaska in 1867 .

Because of his uncompromising stance towards Congress, especially on issues of civil rights for African Americans , his administration is rated as one of the worst in polls by most historians and US citizens today. After the end of his presidency, Johnson remained politically active; In 1875 he was re-elected Senator a few months before his death after two previous applications for Congress had failed. To date, he is the only president elected to the Senate after his term in office.

Life to the presidency

Childhood and youth

Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, the youngest of three children of Jacob Johnson (1778-1812) and Mary Johnson, b. McDonough (1783-1856), born. Jacob Johnson was a constable in the local militia and a doorman at the State Bank of North Carolina . When Andrew was three years old, his father died of a heart attack a few hours after saving three men from drowning. The family was left in poverty. Mary spun and weaved the family and later married the equally destitute Turner Doughtry. Since the provision of the family became increasingly precarious, Johnson followed his brother at the age of ten to an apprenticeship with the tailor John Selby. During this apprenticeship he did not go to school, learned to read from an employee in the tailoring shop and only learned to write as a young adult. He ran away from Selby with his older brother at the age of 15 and lived in Laurens in neighboring South Carolina for two years , where he worked in his profession and unsuccessfully proposed marriage to a local girl. Shortly afterwards he returned to Raleigh. Since he was unable to buy his way out of his apprenticeship with Selby and thus remained contractually bound to him, Johnson left the state to find another job.

Via Knoxville, Tennessee , he came to Mooresville, Alabama and Columbia, Tennessee , and continued working as a tailor. In 1826 he returned to Raleigh to live with his mother and stepfather. They saw no future there and wanted to move with Johnson to his brother and maternal relatives in eastern Tennessee. On the way through the Blue Ridge Mountains , they were troubled by cougars and bears, so they stopped in Greeneville , where they stayed for several years. At first they camped outside the city near Farnsworth Mill , otherwise they had no place to stay. After he found work with a local tailor, they rented rooms in a tavern. In Greeneville Johnson met the daughter of a shoemaker, Eliza McCardle (1810–1876), his future wife. Johnson moved on to Rutledge, Tennessee for professional reasons, but soon returned to Greeneville and married Eliza on May 17, 1827 in Warrensburg, Tennessee, her hometown. They remained married until his death and had five children. In Greeneville, in what is now the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site , they opened their own tailoring shop, which enabled them to achieve great business success while his wife taught him better reading and arithmetic.

Entry into politics and Congressman

Through his interest in debates - he founded an appropriate society and took part in disputes at Tusculum College - Johnson got into politics. During his youth, the then US President Andrew Jackson (1829–1837) made a great impression on Johnson. Jackson was both the first Democratic and the first non-social elite president. Jackson always presented himself as a representative of the "simple (white) people", which Johnson also made his own in his political career. He became mayor of Greeneville in the 1830s. From 1835 he was a member of the House of Representatives from Tennessee ; in 1841 he made the leap to the Senate of the state , from March 4, 1843 to March 3, 1853 he was a member of the House of Representatives of the United States . In the fall of 1844 he was active in the presidential election campaign, in which he supported the Democratic candidate James K. Polk . After the election victory, the relationship between President Polk and Johnson was strained, as the latter's hopes for a government post were not fulfilled. As in previous years, Johnson presented himself in Congress as a representative of the common bourgeoisie . He attributed his strong dislike of the upper class to his poor origins, as he made public speeches throughout his political career. As the biographer Paul H. Bergeron notes, Johnson's political career benefited significantly from his rhetorical skills: In his speeches he addressed the common people, whose voices often helped him to victory. He was able to rely on great support, especially from the white underclass. Johnson was of the opinion that every official owed his democratically legitimized position to the common people alone. Johnson saw himself as a prime example because he did not come from a privileged environment.

During his parliamentary term, the political differences between the slave-free northern states and the slavery- advocate southern states worsened. In particular, the enormous territorial gains that resulted from the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) threatened to throw the balance between the parts of the country out of balance. In particular, the question of how slavery should be dealt with in the new territories was at issue. Johnson, whose household employed slaves himself, was in favor of slavery at the time; the Wilmot Proviso , introduced in 1846 , which provided for a complete ban on slavery in the newly acquired territories, did not find its approval. Ultimately, the Senate rejected the controversial draft. To the Whig -Senator Henry Clay wrote and President Millard Fillmore -driven Compromise of 1850 , which provided for a balance between North and South, endorsed Johnson. He also agreed to the admission of California as a slave-free state. As part of this legislative package, Johnson only voted against the ban on the slave trade in the capital Washington (which was nevertheless passed).

In the late 1850s, intra-party conflicts led the Democrats to put up Landon Carter Haynes as an opponent to Johnson for the next election to the House of Representatives . The Whigs saw this as an opportunity to replace Johnson and did not make their own applicant. Nevertheless, Johnson was able to narrowly win the election for a fifth (two-year) term. After his surprising victory, he was already toying with the idea of running for the US Senate. However, with the Whigs gaining a majority in the State Legislature of Tennessee, the endeavor proved impossible (until 1914 the federal senators were elected not by the citizens but by the state parliaments). The state legislature also decided on the layout of the Congressional constituencies ; the Tennessee parliament had organized the constituencies after the 1850 census in such a way that the Democratic voter potential in Johnson's district was greatly reduced. In 1852 he then declared: “I don't have a political future”, decided not to submit a further application and left the congress at the beginning of March 1853.

Governor of Tennessee (1853-1857)

Since he could count on a not inconsiderable support from Democratic politicians in his state, his party nominated him in the spring of 1853 for the office of governor of Tennessee. During the election campaign the following summer, speeches between Johnson and Whig candidate Gustavus Adolphus Henry took place in several county seats . Johnson then won the gubernatorial election in August 1853 with 63,413 against 61,163 votes. In order to secure votes from the opposing camp, Johnson supported the election of Whig politician Nathaniel Green Taylor to the US House of Representatives.

After being sworn in as governor in October 1853, Johnson enjoyed some political success, although a number of his proposals (such as the abolition of the state bank) were not implemented. In the legislative process he had little influence compared to other governors, as Tennessee's head of government in the mid-19th century still had no veto power . During his tenure, Johnson favored better funding for educational institutions. He wanted to achieve this goal primarily through tax increases at both the state and local levels. The legislature approved this project. He narrowly won the next gubernatorial election in 1855, which caused a sensation in view of the strong Whig competition. Although the Whig Party was in decline on the national stage because of the slavery controversy, it held up longer in Tennessee. Johnson hoped that his re-election would give him more profile in order to gain more political weight for national offices.

In the run-up to the presidential election in 1856 , he promised himself to be nominated as a compromise candidate after the Democratic incumbent Franklin Pierce was no longer nominated. However, Johnson did not campaign actively, although he was very popular locally in Tennessee, and spoke out in favor of the candidate James Buchanan , who was also elected.

US Senator (1857-1862)

In the summer of 1857, Johnson did not run for a third term as governor, but wanted to be elected to the US Senate . Nevertheless, he was actively involved in the election campaign for his successor. After the Democrats with Isham G. Harris were not only able to hold the governor's post, but also gained a majority in the state legislature, the outgoing governor was elected senator in October 1857. Shortly afterwards he took up this position. His family stayed in Tennessee, while the new senator stayed mostly in the capital.

As a Senator, Johnson campaigned for a settlement law similar to the Homestead Act later signed by Abraham Lincoln, just like as a member of the House of Representatives . Several of the Senator's drafts were not accepted or vetoed by President Buchanan. In the late 1850s, he continued to advocate slavery in the southern states, declaring that the Declaration of Independence "All people are created equal" did not refer to African Americans, but rather " Mr. Jefferson meant the white race." With this view, however, he did not differ significantly from many contemporaries.

Before the presidential election in 1860 , Johnson was hoping for his chance to run as a compromise candidate for the Democrats. Although the Democratic nomination convention in the summer of that year quickly bogged down, as no candidate could win the necessary two-thirds majority , Johnson was not considered as a candidate by leading politicians in his party. As tensions between North and South had intensified in recent years, the Democrats were unable to agree on a presidential candidate to succeed James Buchanan, who was no longer running. The party eventually put forward two candidates; Senator Stephen A. Douglas for the North Democrats and Vice President John C. Breckinridge for the South Democrats. Johnson supported the latter in the election campaign, which stood up for the interests of the South. The election winner, however, emerged from Abraham Lincoln , who ran for the newly founded Republican Party and appeared as a (at that time still) moderate opponent of slavery. Lincoln's election to the White House was viewed by many southern states as a fundamental threat to their interests; Even before the new head of state was sworn in, several states declared their exit from the USA in the winter of 1860/61. Although numerous Senators and MPs from the southern states advocated the secession, Johnson spoke out vehemently for the unity of the country. When all the senators from the southern states announced their resignation in the event of a state secession, Johnson appealed to his colleagues (especially addressed to the later Confederate President Jefferson Davis ) not to withdraw from Congress. Johnson pointed out that this would result in a loss of the Democratic majority, which would release President Lincoln from working with the Democrats. Since many Democrats saw themselves as representatives of the southern states, and even were the leading political force there, the interests of the southern states would no longer be represented in Congress. Johnson's appeals went unheard. Although Tennessee also joined the Confederate, Johnson stayed in the Senate and stood up against secession, which Northern politicians welcomed. Johnson stated in the Senate:

“I will not give up this government ... No; I intend to stand by it ... and I invite every man who is a patriot to ... rally around the altar of our common country ... and swear by our God, and all that is sacred and holy, that the Constitution shall be saved, and the Union preserved. "

“I'm not giving up this government; no, I stand by her and I appeal to every patriot to gather together around the altar of our country and to swear by God and all that is sacred to us that the constitution will be protected and unity preserved. "

Military Governor (1862–1865)

In the Civil War that began in April 1861, the northern states brought parts of Tennessee under their control, after which Johnson was appointed by President Lincoln in March 1862 as military governor of his home state. The Senate confirmed the nomination within a short time with a large majority. Through his advocacy for the unity of the country, he also had support in the ranks of the Republicans who were resolutely opposed to secession. As a consequence, the Confederation government confiscated much of Johnson's property, including his home and slaves. During his time as military governor, he took decisive action against sympathizers of the Confederation; especially in the eastern areas of the state, which were largely controlled by Confederates until 1863 .

In view of the loss of the war, Johnson changed his originally positive attitude towards slavery. Johnson stated, "If the institution of slavery leads to the overthrow of the government, the government should have the right to destroy it." The emancipation proclamation previously issued by Lincoln intensified the debate about slavery, the abolition of which Lincoln now made more and more of the actual goal of the conflict in addition to the preservation of unity. As military governor, Johnson reluctantly pushed ahead with the recruiting of African American fighters. This support to troops was very important for the northern states. Already at the beginning of 1864, despite a few military setbacks for the Union in the first half of the year, a victory for the industrialized and logistically better positioned north became apparent.

Election of 1864 and Vice Presidency (1865)

In the 1864 election campaign, President Lincoln's Republicans refused to negotiate an armistice with the Confederation. In the opinion of Lincoln and many of his party friends, such negotiations would mean a de facto recognition of the secession, which would have led the three-year war in vain. They therefore pleaded for a continuation of the fighting until the final victory of the north. Most Democrats were in favor of peace negotiations, but some, like Andrew Johnson, supported Lincoln's positions (War Democrats) . It was therefore decided to run the upcoming election together as the National Union Party ("Party of National Unity").

In June, the National Union Party convention was held in Baltimore , during which Abraham Lincoln was put up for re-election for a second term. For reasons of election tactics, it was decided to have a Democrat from the south set up for the office of Vice President . This was also intended to make clear the intention to reintegrate the breakaway states into the Union under mild conditions. Since Lincoln's previous deputy Hannibal Hamlin did not play an important role in the government anyway, the president agreed to a new appointment. He assigned General Daniel E. Sickles to look for a potential candidate. Johnson, who belonged to the narrower circle of applicants from the start, made it clear in public that he was interested in the post. In the background, people familiar with the military governor were already speaking to the Lincoln team to secure Johnson's candidacy. He hoped the new office would both represent the Southern Democrats in government and boost his political career. In the summer, the National Union Party finally nominated Lincoln and Johnson; Vice President Hamlin's attempt to be re-established failed at the party convention.

In the election campaign, Johnson even made several public appearances, where he campaigned for the continuation of the war until the reunification of the country. The presidential election in November 1864 was clearly in Lincoln's favor: He defeated the Democratic candidate, George B. McClellan , with 55 percent to 45 percent of the vote. Since most of the democratically dominated states of the south belonged to the Confederation, the combination of Lincoln and Johnson prevailed in the electoral committee with 212 against 21. The course of the war in the summer and autumn months of 1864, when the tide turned decisively in favor of the north (such as the capture of Atlanta by the Union army) , played a special role in this clear victory .

After the election, the war came to a swift end. Even before Johnson was sworn in as Vice President, Lincoln was able to get the 13th Amendment to the Constitution through Congress, which declared slavery to be illegal throughout the United States. In Tennessee, a new state constitution went into effect in early 1865 that banned slavery. Its execution was one of Johnson's last official acts as military governor. Lincoln was sworn in for his second term on March 4, 1865, and Andrew Johnson took the oath to be the new Vice President before the Senate plenum. At his inauguration , the new Vice President caused a public sensation because he had appeared drunk for the celebrations. Lincoln then rejected criticism of Johnson's behavior and insisted that Johnson was not a drunkard . As Vice President Johnson played no important role in the government; by virtue of his office, he chaired the Senate, where he chaired several meetings without significant resolutions, since organizational matters were on the agenda at the beginning of the electoral term.

Presidency (1865–1869)

In office after Lincoln's death

On April 14, 1865, Good Friday , Johnson met the President in person for the first time since the swearing-in. A few days earlier, the Confederation had capitulated. He spoke to Lincoln in favor of severe punishment for the leaders of the southern states. "Treason is a crime and must be made odious" ("Treason must be made hated and traitors must be punished"), said the Vice President. Lincoln had invited his deputy to an evening theater performance that day, but the vice president refused to accept. During this performance at Ford's Theater , the president was shot in the head by fanatical southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth . The next morning, Lincoln was pronounced dead. As the constitution did not provide (it did not do so until the 25th Amendment of 1967 ), but sanctioned by the precedent of President Harrison's death since 1841 , the office of president was passed to the vice-president for the remainder of the term, and Andrew Johnson became sworn in as 17th President of the United States by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase on the morning of April 15, 1865 . Johnson asked Lincoln's ministers to remain in his cabinet that same day . Secretary of State William H. Seward and several other Ministers remained in their posts until the end of Johnson's term in March 1869. Johnson was the third Vice President after John Tyler in 1841 and Millard Fillmore in 1850, who had to succeed him for the remainder of the term due to the President's death. He was also the first of a total of four presidents who came into office through a fatal assassination attempt on their predecessor.

According to Booth's plan, Vice President Johnson, Secretary of State Seward and General Ulysses S. Grant should have been murdered in addition to Lincoln . However, George Atzerodt , who was supposed to murder Johnson, shrank from the act. The attack on the Foreign Minister did not end fatally with the intervention of his son; General Grant was out of town at the time of the crime. All of the conspirators were quickly caught and hanged in July 1865 . Only the doctor Samuel Mudd , who had given Booth medical care while he was on the run and received a prison sentence, was pardoned by Johnson in early 1869.

Reconstruction begins

The main task of Johnson's presidency was the so-called reconstruction , i.e. the resumption of the former confederation in the United States. The political disputes over it shaped his term of office. It was about the conditions under which the southern states fully reintegrated into the United States, and the rights that the freed slaves should be granted.

Since the Congress did not meet again until December 1865 after the President had been sworn in (the legislature met much less often than today), Johnson had the opportunity in the months to come to implement many of his ideas on reconstruction by means of presidential decrees . First, he ordered that the former leaders of the Confederacy and rich Southerners the oath to the loyalty to the Union only for a place given by the President for clemency were allowed to pass. By the summer of 1865, Johnson pardoned more than 13,000 wealthy southerners. As the historian Vera Nünning writes, he enjoyed the fact that the southern upper class, by whom he felt oppressed especially in earlier years, was now dependent on his mercy.

The first tensions between the president and the Radical Republicans arose when, during his first few months in office in the occupied southern states, he appointed a number of military governors from the former southern elite, some of whom had close ties to the leaders of the rebellion. In addition, he gave the southern states no conditions for the preparation of new ( republican ) state constitutions. He even made the ratification of the ban on slavery a condition only in background discussions. The Radical Republicans, outnumbered in Congress in 1865, were alongside the Conservative Republicans and the minority Democrats a group of Senators and MPs who advocated harsh punishment for the former Confederates. They also spoke out in favor of extensive civil rights for the former slaves; black men, for example, should also have the right to vote . They also advocated treating the states of the former confederation as occupied territories. Johnson, on the other hand, wanted the southern states to be fully reintegrated into the Union as quickly as possible and without extensive conditions. Through mild admission conditions, with the exception of the ban on slavery, his aim was to restore the old social structures and thus also to secure the position of the Democratic Party in the South (unlike today, since African Americans predominantly vote democratically, blacks voted for the Republicans at that time than the party that supported the Abolished slavery). In addition, as he made clear in his annual message to Congress in December 1865, Johnson was of the opinion that the southern states had never legally withdrawn from the United States. By appointing democratic military governors from the southern elite, the president also limited the right to vote to those who had a vote before the civil war. The introduction of black codes , which were very similar to the earlier slave codes , prevented many African Americans from participating in elections and thus denied political influence. The Radical Republicans in particular sharply criticized this policy, while Johnson saw himself in the Lincoln tradition of being lenient towards the South. In fact, the Radical Republicans had also viewed Lincoln's reconstruction plans as too compliant.

Johnson's policy of obstruction to the Freedman's Bureau caused further impairment for the African American . This was under the supervision of the Ministry of War and was supposed to provide the former slaves with a livelihood outside of the plantations through confiscated land from the property of the planters. However, the president decided that this land could not be leased to black people, but had to be returned to the former slave owners. The factual restrictions on the right to vote and the provisional governments appointed by Johnson continued to experience considerable disadvantages for blacks. Since many blacks were unable to start their own existence, they often continued to work on the cotton plantations under conditions similar to those before the war .

The reconstruction conflict escalated

After the war, many Republican members of Congress spoke out in favor of far-reaching civil rights for the freed slaves. Johnson, who like many of his contemporaries had a racist worldview , not only viewed blacks as intellectually and morally inferior to the white race, he also doubted that peaceful coexistence was even possible. Only their physique is stronger in order to be able to carry out hard and low work. Johnson said to Thomas Clement Fletcher , the governor of Missouri , "This is a country for whites, and by God, as long as I am president, there will be a government for whites too." Another conflict between the Congress majority and the President arose from the question of who was actually responsible for upholding civil rights and the right to vote. While Johnson saw the individual states as responsible for electoral law, the Republicans were of the opinion that the federal government had powers to protect the electoral law in the long term. In response to criticism, Johnson replied that it was an arrogance of power on the part of the White House to give African Americans in the southern states the right to vote. This is the sole responsibility of the respective state governments. This is also evident from the fact that in the summer and autumn of 1866, after fatal attacks on blacks and Republicans in the south, he refused to intervene with the authority of the national government; for example through legal measures or the dispatch of troops to protect the minority. Both radicals and moderate Republicans strongly condemned Johnson's policies in this regard. Johnson, on the other hand, blamed the increasing riots on the Republicans, who had purposefully incited the African Americans through their course.

Since Johnson expressed his willingness to compromise insofar as he promised to secure the former slaves "the right to freedom and paid work", the Republicans in Congress worked out a compromise under the leadership of Senator Lyman Trumbull . The result was the Civil Rights Act of 1866 , a law protecting those rights of African Americans whose approval Johnson had previously indicated. The assessment of the senators around Trumbull that the president would approve the bill turned out to be wrong; he put his veto on March 27, 1866 . For Johnson, Radical Republicans demanded that African-Americans should be given full voting rights by law and natural rights at the same level as the Civil Rights Act. As historian Vera Nünning explains, after the Civil Rights Act, Johnson saw Congress as consisting almost entirely of radicals who had set themselves the goal of undoing its previous reconstruction policy by giving African Americans extensive voting rights. In doing so, however, the president fatally misjudged the willingness of the senators and members to compromise before the law. The historian Paul H. Bergeron also writes that Johnson had turned Congress against him through his entire term of office through his personal uncompromising attitude. Because Congress, including Johnson biographer Annette Gordon-Reed , was initially quite ready to make concessions to the White House in order to be able to work with the President. Johnson's veto not only turned the radicals against him; moderate Republicans also viewed his behavior, which in fact denied the federal government any intervention to protect the black minority, as an affront. Johnson's actions had far-reaching political consequences, as radicals and moderate Republicans from then on cooperated much more closely. A few weeks later, a coalition of both blocs was able to override the presidential veto against the Civil Rights Act with the necessary two-thirds majority, which means that the bill came into force even without the approval of the president.

Another reaction to Johnson's course was the enforcement of the 14th Amendment , which declared blacks citizens of the United States, which constitutionally guaranteed formal equality before the law (even if practical equality was far from being achieved). Johnson spoke out vehemently against the addition, which he viewed as an act of revenge by Congress against the South. Although the president has no means to prevent the passage of a constitutional amendment in Congress, he tried (in vain) to persuade the states that had yet to ratify the amendment to reject it.

Congressional elections in 1866 and the rise of the Radical Republicans from 1867

In late autumn 1866, there were congressional elections in the middle of the presidential term . And although the president was not on the ballot, political observers at the time viewed these elections as a de facto referendum on Johnson's previous government work. Johnson had largely lost the support of Republicans in Congress due to his uncompromising approach in his reconstruction policy. He therefore decided to intervene in the election campaign himself to convince the population of his course. He hoped that a new Congress with more Democrats would support his approach in the future. From the end of August 1866 he personally traveled all over the country, which was still unusual at the time, in order to raise the mood against the radical republicans in dozens of speeches. In a speech in Cleveland on September 3, 1866, he stated :

“And because I stood now as I did when the rebellion commenced, I have been denounced as a traitor. My countrymen here to-night, who has suffered more than I? Who has run greater risk? Who has borne more than I? But Congress, factious, domineering, tyrannical Congress has undertaken to poison the minds of the American people, and create a feeling against me in consequence of the manner in which I have distributed the public patronage. "

“And because I am still where I was when the rebellion began, I have been denounced as a traitor. My countrymen, who has suffered more than me? Who took a greater risk than me? Who has endured more than me? But the Congress; the partisan, domineering and tyrannical Congress has begun to poison the minds of the American people and to stir a mood against me for the way I have distributed public funds. "

Johnson hoped on this so-called swing around the circle trip to convince the population with his rhetorical skills, as he had been able to do in earlier years. But this time, with his sometimes extremely provocative appearances, he met with a majority of rejection. His attempt to involve the very popular Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant also failed, since Grant - not very convinced of Johnson in private - seemed to support the course of the White House at best half-heartedly. The Radical Republicans, for their part, not only condemned Johnson's previous policies, but also described his appearances, which were unusual for a president at the time, as unworthy of a head of state.

In the end, the 1866 congressional election turned out to be a disaster for Johnson. The Radical Republicans made massive gains; they achieved a two-thirds majority in both legislative chambers. A journalist from the northern states later wrote that Johnson had lost about a million votes to the radicals in the northern states through his campaign appearances. Johnson's violent attacks on the Republicans encouraged them to go on a course of confrontation with the White House by advancing their political goals even more vigorously in the future.

Even before the newly elected Congress was constituted in March 1867, the conflict between Parliament and President came to a head: In January 1867, the old Congress passed a law to protect African Americans' voting rights in Washington, DC The president immediately exercised his right of veto Use. In his veto message, he stated that encroachment on the rights of the individual states would be unconstitutional for the simple reason that not all states from the south had been admitted to the Union. On the same day, Congress defied the veto with the necessary majorities. In the following months the parliamentarians brought the Reconstruction Acts on the way, which reversed the previous policy of the White House, whereby they again overruled Johnson's vetoes. With the bundle of laws, the former Confederate States were divided into five districts, the military governors were replaced by generals from the northern states . If necessary, it was possible for them to proclaim martial law in order to enforce the 14th Amendment to the Constitution . It was also stipulated that the southern states could only be fully admitted to the Union after its ratification. This took place under these conditions between 1866 and 1870. Johnson resisted these measures through the summer of 1867 by issuing orders to the generals, within the framework of his executive powers as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces , in order to prevent the execution of laws which he disapproved of. Little by little he replaced the generals with more acceptable personalities. By autumn 1867 he believed that he had largely achieved his goal.

In addition to the Reconstruction Acts, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in the spring of 1867, again against Johnson's veto . This was in response to Johnson's suggestion that he would fire ministers who disagreed with him on reconstruction policy. The new law required the Senate to approve the dismissal of cabinet members. So far, the president had only needed the approval of the Congress Chamber to appoint a minister, not to dismiss a minister. From the Republicans' point of view, this was intended to prevent the dismissal of ministers whom Lincoln had appointed. Johnson's view that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional was upheld in 1926 by the Supreme Court , which repealed a similar law (the Tenure of Office Act itself was repealed by Congress in 1887 after all subsequent presidents had also criticized this law) . An alleged violation of that law by Johnson was cited as the main reason for his proposed impeachment the following year.

Impeachment proceedings 1868

As early as the summer and fall of 1867, some Republicans in Congress came to believe that the solution to the ongoing conflict with the President would be the impeachment of Johnson. Many Radical Republicans said that "the reconstruction could fail because of resistance from a stubborn president." Therefore, one began to look in the relevant parliamentary committees for evidence of illegal actions by Johnson that would justify his dismissal (unlike in parliamentary democracies , in the presidential system of the USA the head of government cannot be removed from office for political reasons, but only for illegal acts) . When Johnson dismissed two other unpleasant generals in the south against the will of the MPs, the fronts between him and the Congress majority hardened further.

In the late summer of 1867, while the Senate was not in session, Johnson tried to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton , who had already served under Lincoln, from office due to political differences . When he refused to resign, Johnson installed General Grant as acting minister. Grant followed the President's request, but expressed serious doubts about the legality of the presidential action. That was the turning point: after Congress convened again in November 1867, the Judiciary Committee passed a resolution in the House of Representatives to propose to the Senate the impeachment of the President. However, this first draft was rejected by a clear majority on December 7, 1867 (57 against 108). This was preceded by long debates in Congress as to whether Johnson was actually accused of illegal activities or "the most serious crimes against the United States," as the constitution stipulated as a prerequisite for impeachment.

Since Secretary of War Stanton was formally still in office, Johnson asked the Senate in January 1868 to dismiss the minister. He also informed the senators that he had appointed Grant as interim minister. The Senate rejected the President's motion, stating that Stanton, not Grant, was in charge of running the Department of War. Although Johnson refused to acknowledge this, Grant withdrew with reference to the Senate resolution. The popular general was already traded as a Republican presidential candidate for the election at the end of the year. After Grant's withdrawal, Johnson defied the Senate by declaring Stanton dismissed and appointing Civil War General Lorenzo Thomas as the new Secretary of War. Stanton, however, remained de facto in his post as the President's actions were formally ineffective without the approval of the Senate.

With his actions, the confrontation between Johnson and Congress reached a new high point; on February 24, 1868, the House of Representatives voted 128 to 47 to initiate impeachment proceedings against the President. It was the first ever impeachment against an American president (such plans had already existed against John Tyler in 1842, although they had already been rejected in the committees due to their insubstantiality). The process met with a very high response in the media. The main charge was the violation of the Tenure of Office Act: Johnson had acted unlawfully with Stanton's dismissal and the appeal of Thomas without Senate approval. After the resolution was passed in the House of Representatives, the Senate began deliberations. He has the role of a court in the proceedings, which can remove the president with a two-thirds majority. During the roughly three-month deliberations, Johnson, on the advice of his advisors, did not publicly comment on the allegations or the impeachment itself. Behind the scenes, however, he spoke to moderate Republicans and promised various concessions in his future administration should he avoid dismissal. He told Senator James W. Grimes that he would no longer actively obstruct the reconstruction policy of Congress. When the most extensive motion, item 11, was voted on on May 16, 1868, 35 senators voted guilty , 19 not guilty . Another vote on May 26 on two other charges brought the same result. This missed the two-thirds majority with one vote necessary for the removal, seven Republicans had stood against the party line.

In addition to the concessions that Johnson had made, the historian David O. Steward explains Johnson's eventual acquittal with an even lower confidence in his potential successor. Since the position of Vice President remained vacant for the remainder of the term of office due to Johnson's promotion to the highest office of state after Lincoln's death (the legal regulation for the retrospective appointment of a Vice President was only created in 1967 with the 25th Amendment to the Constitution ), according to the then valid version of the Presidential Succession Act the President pro tempore of the Senate to take office. In 1868 it was Benjamin Wade , a radical republican who, even by moderate republicans, had an all too hard will to punish the south. Wade was also said to have ambitions for the office of president, and as acting president he would have had a significantly better starting position in the election in November 1868. A newspaper article from this period stated: "Andrew Johnson is innocent because Ben Wade is guilty of being his successor".

Historians explain the reluctance of some senators to vote for the impeachment of Johnson, also with the significant constitutional significance, since a precedent would have been set in case of an ousting . Extremely restrictive legal standards were derived from the acquittal, so that the impeachment turned out to be a purely political weapon against the president. The next impeachment proceedings did not begin until more than a century later, in 1974 against Richard Nixon over the Watergate affair . In both the Watergate scandal and the failed impeachment of Bill Clinton in 1999, media parallels were drawn with Johnson 1868.

Foreign policy

Johnson retained Lincoln's Secretary of State William H. Seward until the end of his term in 1869. Both politicians agreed that there would be no realignment of foreign policy . At that time, due to the strong focus on reconstruction, foreign affairs played only a subordinate role. At the time of Johnson's inauguration, France had already intervened in Mexico , with the aim of helping the conservatives in Mexico to power after the civil war that had already been lost and to establish a monarchy dependent on France . The US government strongly condemned this action and asked France to withdraw its troops. The presence of European power in a neighboring country to the United States was viewed as improper interference in the American hemisphere according to the Monroe Doctrine . Johnson could initially envision a harsh, even violent, reaction to the French crackdown, but Seward was more advocate of diplomacy behind the scenes. This enabled him to convince the president, who gave him a free hand in the talks. Seward's efforts were effective in that the French government agreed to the gradual withdrawal of its soldiers, which was carried out by November 1867.

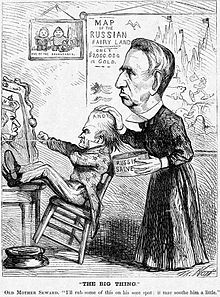

The most important foreign policy event of Johnson's presidency was the purchase of Alaska from Russia for a price of 7.2 million dollars (128 million dollars in today's purchasing power). Seward was very active in this endeavor, with the President allowing him great freedom. In addition to the American expansionist striving for the ideology of the Manifest Destiny , the Foreign Minister justified the purchase with a service to Russia. During the civil war, unlike the United Kingdom, Russia appeared as an ally of the northern states, but in 1867 was in dire financial straits. The sale of the roughly 1.7 million square kilometers of territory was a welcome source of income for the Tsarist Empire. The United States Senate ratified the treaty on April 9, 1867. However, the approval of the money needed to buy Alaska was delayed by over a year due to opposition within the House of Representatives.

Indian policy

Johnson followed questions of Indian policy very closely and intervened on several important points. His Interior Minister James Harlan , initially of considerable importance for Indian affairs , tried to enforce the establishment of a corresponding territory under federal supervision by trying to open the Indian territory with the Harlan Bill (Senate Bill No. 459) to the construction of railways and economic use. The Senate rejected this project, which would have given the area an almost colonial status.

President Johnson appointed a friend of the Home Secretary named Dennis Nelson Cooley as the commissioner for Native American Affairs in July 1865 . This negotiated with the two quarreling Cherokee groups in Indian territory, where he reached an agreement with the southern group. But the President refused to submit the contract to the Senate. The commissioner had to renegotiate, which ultimately led to a unified contract covering both groups being signed and approved by the Senate. This in turn prevented the breaking up of the tribe, which is now the largest tribe in North America.

In November 1868, the federal government signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie 1868 , which designated the entire area of what is now the state of South Dakota west of the Missouri, including the Black Hills, as Indian land for unrestricted and unmolested use and settlement by the Great Sioux Nation . However, due to a gold rush that began in the 1870s, this agreement was de facto not permanent. Since the Indians do not accept any monetary compensation awarded to them and claim the land back, disputes between the tribes and the federal government continue to this day.

Also relevant to Indian policy was that the 14th Amendment did not make reservation Indians American citizens. However, since this was not a matter of dispute, unlike among African Americans, this did not result in any differences between Congress and the Johnson administration.

Election 1868 and termination of the term of office

In early July 1868, the Democratic Party held its nomination convention for the November presidential election in which Johnson wanted to run. In the first ballot he received 65 delegate votes and achieved only the second-best result after George H. Pendleton , who was viewed as a favorite from the start. Its 105 votes were also not enough for nomination. With each subsequent vote, the incumbent continuously lost support, and in the end only the delegation from Tennessee was behind him. In the 23rd run, the New York Governor Horatio Seymour was finally set up. Delegates from the north in particular had thwarted Johnson's candidacy. But delegates from the south had also come to the conclusion that in view of the fierce political conflicts in the past few years, Johnson's re-election would be a hopeless undertaking.

After his defeat at the party congress, the last eight months of Johnson's presidency were also marked by conflicts with Congress. Although he no longer actively stood in the way of the legislature's reconstruction policy, he continued to make active use of his right of veto, for example against a law that obliged him to forward the ratification of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution by some southern states more quickly to Congress ( which Johnson deliberately delayed). This law was also passed against the president's veto. In the fall of 1868, he submitted several proposals to Congress to extend the presidential term to six years and to exclude re-election. He also called for a term limit for federal judges. However, the MPs ignored these suggestions.

In the election campaign between Seymour and General Grant, which was run by the Republicans, the outgoing president played practically no role. Although Seymour had hoped for his advocacy, the president only mentioned the Democratic candidate once in October towards the end of the campaign. There was no official declaration of support. The presidential election on November 3, 1868, was the politically inexperienced, but very popular because of his achievements as commander in the civil war Grant. In the remaining four months until he took office in March 1869, Johnson issued several pardons for former Confederates. So he pardoned former Southern President Jefferson Davis at Christmas 1868 . In his last annual message to Congress in December 1868, he once again advocated the withdrawal of the Tenure of Office Act.

Johnson's tenure as president ended on March 4, 1869 with the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant. Contrary to tradition, Johnson refused to attend the ceremony. Marked by mutual dislike, Grant also made it clear in advance that he did not want to go to the celebrations in the same carriage with Johnson, as was the case with presidential handovers up to now and later.

After the presidency

Unlike other American presidents, Johnson did not see his political career as ended after the end of his term in office. The momentary retreat into private life apparently bored Johnson; He was also looking for a new job after he suffered a private loss in 1869 with the suicide of his son Robert. As expected by political observers, Johnson ran again for the Senate in the fall of 1869 after the Democrats regained a majority in the State Legislature of Tennessee. Nonetheless, there was resistance from within his own ranks, so that in the end he was only one vote short of victory. Henry Cooper emerged victorious from this vote, prevailing with 54 against 51 votes. In the summer of 1872, Johnson ran for the only congressional constituency of Tennessee for the House of Representatives. Although the Democrats nominated Benjamin Franklin Cheatham rather than him, he ran for election as a non- party. Since the votes of the Democratic regular voters were divided between two applicants, the Republican Horace Maynard was able to win the election.

In January 1875, Johnson was elected to the Senate again at the third attempt by the Tennessee State Legislature. His surprising triumph was widely received in the print media . The St. Louis Republican newspaper reflected it as "the most splendid personal triumph in the history of American politics." Johnson is to date the only president elected to the Senate after serving in the White House. Besides him, only John Quincy Adams had become a member of Congress after the presidency, albeit in the House of Representatives. In March 1875, Johnson took the oath as a senator. During his short time in the Senate, he criticized President Grant's policies and called on him to withdraw the Union's occupation forces from the southern states. Grant refused, however, and the withdrawal was not made until 1877.

Andrew Johnson died on July 31, 1875 shortly after his arrival in the Senate, near Elizabethton in Carter County, Tennessee at the age of 66 years at a stroke . He was buried outside Greeneville in what is now the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery . According to his request, he was wrapped in an American flag with a copy of the Constitution attached.

Aftermath

According to polls among Americans, Johnson is considered one of the most underrated US presidents across party lines. In a 2010 poll by Siena College, for example, he came last among the most popular presidents.

In the 21st century, Johnson biographers such as Hans Trefousse are particularly critical of his intransigent attitude towards Congress in the context of Reconstruction and his associated refusal to grant African Americans more rights. Due to personal stubbornness and a racist worldview , Trefousse said, Johnson was unable to work effectively with Congress. The historian Vera Nünning is of the opinion that Johnson's policy has missed the chance to impose the equality of blacks on the southern states, which were demoralized after the civil war, by means of political pressure. Paradoxically, however, Johnson's stance against more rights for African Americans motivated Congress and the state parliaments even more to enforce the 14th and 15th amendments against his will.

As the Johnson biographer Albert Castel notes, the negative image of the 17th US President that is widespread today was historically by no means consistent. In the first decades of the 20th century in particular, according to Castel, positive accounts of Andrew Johnson's administration appeared. For example, in his 1913 book History of the Reconstruction Period, historian James Schouler described Johnson as a far-sighted politician who resolutely opposed a vengeful Congress against the South and sought a fair incorporation of the former Confederation. Woodrow Wilson , himself US President from 1913 to 1921, also dealt with the 17th President in the years of his academic activity (before his term in office). He described Johnson as politically awkward due to his social background, but admitted that he had acted in the Lincoln tradition of treating the southern states with indulgence. Towards the end of the war, Lincoln actually spoke out in favor of mild admission conditions in order to be able to reintegrate the former confederation into the USA without giving the (white) population of the south a feeling of humiliation. The historian William Archibald Dunning also came to similar conclusions as Wilson. With the start of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Castel continued, Andrew Johnson was again sharply condemned for his policies against blacks, who continued to experience significant inequality through racial segregation and discriminatory election tests until the 1960s . The historian Vera Nünning states, however, that despite the generally not very positive view of Johnson in the 21st century, historiography is now trying to find a more balanced picture, “by tracing the weaknesses back to his social origin and the values and norms prevailing in the south, from which he, like most of his compatriots, could not escape ”. She also said Johnson was more realistic about the extent of racial discrimination in the South than the Republican majority in Congress. The Johnson biographer Annette Gordon-Reed points to Johnson's social background and the extremely difficult times in which he took over the leadership of the United States. For them, his lifelong hostile attitude towards blacks is related to the fact that he identified them as those who, in cooperation with the plantation owners, blocked the rise of the white lower class in the southern states.

In the movie

In 1942, the film Tennessee Johnson was a film adaptation of the life of Andrew Johnson with Van Heflin in the leading role. Tennessee Johnson , however, received a largely negative response; The actor Zero Mostel criticized the film, in which Johnson is portrayed as a champion of democracy, as too glorifying. Furthermore, the film adaptation did not always adhere to historical facts; for example, Johnson never appeared in person in the Senate during the impeachment process. Also from a commercial point of view, Tennessee Johnson was not successful because a loss was made.

swell

Finding aids:

- Johnson, Andrew (1808-1875) Papers 1846-1875. Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville TN 1958 (PDF) .

- Index to the Andrew Johnson Papers (= Presidents' Papers Index Series. ). Library of Congress , Manuscript Division, Reference Department, Washington 1963 (PDF) .

Editions:

- Speeches of Andrew Johnson, President of the United States. With a Biographical Introduction by Frank Moore. Little, Brown and Co., Boston 1865 (digitized version) .

- Lilian Foster: Andrew Johnson, President of the United States. His Life and Speeches. Richardson & Co., New York 1866 (digitized version).

- LeRoy P. Graf, Ralph W. Haskins, Paul H. Bergeron (Eds.): The Papers of Andrew Johnson. 16 vols. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville 1967-2000 (reviews at the beginning and end of the project; preview of vol. 7 , vol. 12 , vol. 14 , vol. 16 ).

literature

For an annotated bibliography of Johnson literature from 1877 to 1998:

- David A. Lincove: Reconstruction in the United States. An Annotated Bibliography (= Bibliographies and Indexes in American History. Vol. 43). Foreword by Eric Foner . Greenwood Press, Westport CT 2000, ISBN 0-313-29199-3 , Studies on Andrew Johnson, 1864-1868, pp. 82-102 (preview) .

Additional:

- Albert Castel: The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (= American Presidency Series. ). 4th edition, University Press of Kansas, Lawrance 1979, ISBN 978-0700601905 .

- James David Barber: Politics by Humans: Research on American Leadership. Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-8223-0837-1 , Chapter I.2: Life History. Pp. 24–52 (preview) .

- Hans L. Trefousse: Andrew Johnson: A Biography. WW Norton & Company, New York 1989, ISBN 0-3930-2673-6 .

- David O. Stewart : Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, ISBN 978-1-4165-4750-1 .

- Paul H. Bergeron: Andrew Johnson's Civil War and Reconstruction. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville 2011, ISBN 978-1-57233-794-7 (preview) .

- Annette Gordon-Reed : Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, ISBN 978-0-8050-6948-8 .

- Vera Nünning : Andrew Johnson (1865–1869): The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 44 historical portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama. 6th, continued and updated edition. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-58742-9 , pp. 194-204.

Web links

- Andrew Johnson in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- Biography ( memento from January 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on whitehouse.gov (English)

- American President: Andrew Johnson (1808-1875) , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia (English, editor: Elizabeth R. Varon)

- The American Presidency Project: Andrew Johnson. University of California, Santa Barbara database ofspeeches and other documents from all American presidents

- Andrewjohnson.com - Information and excerpts from Harper's Weekly on Andrew Johnson

- Andrew Johnson in the NGA

- The governors of Tennessee (English)

- Life Portrait of Andrew Johnson on C-SPAN , July 9, 1999, 158 minutes (English-language documentation and discussion with historians Michael Les Benedict and Robert Orr as well as a guided tour of the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site )

- Andrew Johnson in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Remarks

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 28, 29.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: p. 196; Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Paul H. Bergeron: Andrew Johnson's Civil War and Reconstruction. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Andrew Johnson: Life before the presidency . Miller Center of Public Affairs , University of Virginia, accessed April 19, 2018.

- ^ Albert Castel: The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (American Presidency Series) , 4th Edition, University Press of Kansas, Lawrance 1979, p. 5.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 51.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 52-55.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 58-60.

- ↑ "Mr. Jefferson meant the white race ". LeRoy P. Graf, Ralph W. Haskins (Eds.): The Papers of Andrew Johnson. Vol. 3: 1858-1860. 1972, p. 320.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Hans L. Trefousee: Andrew Johnson: A Biography. WW Norton & Company, New York, p. 131.

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: p. 197.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 72.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 70.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 76-80.

- ↑ Eric L. McKitrick: Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1960, p. 136.

- ↑ a b Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: pp. 197 f.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 87.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2009. p. 418.

- ↑ a b Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194-204, here: p. 198; David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, pp. 36-39; Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 88-91.

- ^ Andrew Johnson: Domestic Affairs . Miller Center of Public Affairs , University of Virginia, accessed April 19, 2018.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, p. 16.

- ^ "This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men". Eric L. McKitrick: Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988, p. 184.

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: pp. 200–201; David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ a b Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: pp. 199–200.

- ^ Paul H. Bergeron: Andrew Johnson's Civil War and Reconstruction. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, p. 60.

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: p. 200.

- ↑ Andrew Johnson: Cleveland speech, Sept. 3, 1866 , American History.

- ↑ a b David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, pp. 59-60.

- ^ A b Andrew Johnson: Campaigns and Elections . Miller Center of Public Affairs , University of Virginia, accessed April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: pp. 200–202.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, pp. 74-76.

- ^ Case law - find law: Myers v. United States .

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: p. 201.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, pp. 109/111.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 124.

- ↑ David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 124-126.

- ^ "Andrew Johnson is innocent because Ben Wade is guilty of being his successor". Quoted by David O. Stewart: Impeached. The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York NY 2010, p. 317.

- ↑ Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: p. 202.

- ^ A b Andrew Johnson: Foreign Affairs . Miller Center of Public Affairs , University of Virginia, accessed April 19, 2018.

- ^ Primary Documents in American History: Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska.

- ↑ C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa: Crooked Paths to Allotment. The Fight Over Federal Indian Policy After the Civil War. University of North Carolina Press, 2012, p. 60.

- ^ Francis Paul Prucha: The Great Father. The United States Government and the American Indians. University of Nebraska Press, 1995, pp. 436 f.

- ↑ History of the Laramie Treaty on ourdocuments.gov (English)

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 140-141.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 141-143.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 142; Swearing-In Ceremony for President Ulysses S. Grant , US Senate (English).

- ^ Andrew Johnson: Life after the Presidency . Miller Center of Public Affairs , University of Virginia, accessed April 19, 2018.

- ^ "The most magnificent personal triumph which the history of American politics can show". Quoted by Albert Castel: The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (American Presidency Series) , 4th Edition, University Press of Kansas, Lawrance 1979, p. 218.

- ↑ a b c d Vera Nünning: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869). The dispute over the reconstruction. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 194–204, here: p. 203.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Poor Andrew Johnson: Poll Ranks Worst (and Best) Presidents , Politicsdaily.com (English).

- ^ Andrew Johnson: Impact and Legacy . Miller Center of Public Affairs , University of Virginia, accessed April 19, 2018.

- ^ Albert Castel: The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (American Presidency Series) , 4th edition, University Press of Kansas, Lawrance 1979, p. 220.

- ^ Albert Castel: The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (American Presidency Series) , 4th Edition, University Press of Kansas, Lawrance 1979, pp. 218-219.

- ^ Albert Castel: The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (American Presidency Series) , 4th Edition, University Press of Kansas, Lawrance 1979, p. 221.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Annette Gordon-Reed: Andrew Johnson (= American Presidents Series. ). Times Books / Henry Holt, New York City NY 2011, pp. 11-12, 24-25.

- ^ Zero Mostel: A Biography. Jared Brown, Atheneum, NY 1989, pp. 35-36.

- ^ Tennessee Johnson , IMDb (English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Johnson, Andrew |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | 17th President of the United States (1865–1869) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 29, 1808 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Raleigh , North Carolina |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 31, 1875 |

| Place of death | Carter Station , Tennessee |