Zachary Taylor

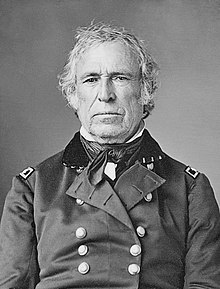

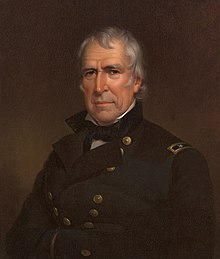

Zachary Taylor (born November 24, 1784 in Barboursville , Orange County , Virginia , † July 9, 1850 in Washington, DC ) was the twelfth President of the United States . He served from March 4, 1849 until his death on July 9, 1850 and was the second president after William Henry Harrison to die during his tenure.

Taylor was in a wealthy planter born family and grew up in the border region, the "Frontier" of Kentucky on. Like his eldest brother, Taylor chose an officer career and joined the United States Army in 1808 . In addition, he cultivated his own plantations and was active as a land speculator, so that at the end of his life he had considerable wealth. As a military leader, he first drew attention to himself during the British-American War , when he defended Fort Harrison against an attack by the Indians in 1812 . After a brief discharge from the army after the war, several official assignments in the "Frontier" followed. In the 1830s Taylor fought in the Black Hawk War and the Second Seminole War , where in 1837 he brought about the only open field battle in this conflict at Okeechobee . He then commanded a military district encompassing Indian territory , which was at the end of the path of tears . During the Mexican-American War he led his own army, with which he won the battles of Buena Vista , Palo Alto and Monterrey , which made him a national hero and in 1847 brought him promotion to major general .

In 1848 the Whig Party nominated him as their presidential candidate , not least because they wanted Taylor's wartime glory to make them forget their own opposition to the Mexican-American War. As a result, the Whigs conducted a personalized election campaign that was exclusively focused on Taylor and dispensed with a program. In the election he prevails against the Democrat Lewis Cass . The dominant theme of his politically inexperienced presidency was the slave question , which dominated the debate about the admission of New Mexico , California and Utah to the Union. Taylor surrounded himself with a cabinet that lacked influence over Congress , and he himself showed little concern for a base in the House or Senate . During his tenure he moved closer and closer to the abolitionist northern wing of the Whigs and alienated himself from the planters of the southern states . Before this conflict could be temporarily calmed down in the compromise of 1850 , Taylor died after only 16 months in office. The greatest of only a few achievements of his historiographically mostly negative term of office was the conclusion of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty . In addition, Taylor's steadfast defense of the Union against the first attempts at secession by the slave states is positively highlighted.

Life

Family and upbringing

Taylor was born on November 24, 1784 on the Montebello plantation in Orange County, Virginia, the third son and one of nine surviving children of Richard Taylor (1744-1829) and Sarah Dabney Taylor (1760-1822), née Strother. The place of birth was near Montpelier , the country residence of the later President James Madison , who was his second nephew . Taylor's father was an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War , at times a member of the Virginia General Assembly and a member of one of the most important planter families in the state that had lived in America for 150 years. In 1779 he married his wife, who also came from a wealthy background. For his officer service he received an extensive donation of land near Louisville in Kentucky . Since Taylor's plantation in the Tidewater region was smaller and the soil was depleted due to excessive tobacco growing , he decided to move. For an initial exploration, he left the pregnant woman with both sons in Virginia with a cousin, where Zachary Taylor was born. After the father had taken possession of the land near Louisville and prepared it for settlement, he brought the family after seven months. In August 1785, the Taylors finally moved into the 160 hectare Springfield plantation located a few kilometers east of Louisville in Beargrass Creek .

Taylor grew up in what was then the border region of the United States, the “frontier” , which in the eyes of the settlers was characterized by “wilderness” . The European settlers in the broader sense saw themselves as right to inhabit this wilderness and to make it economically usable, and to bring the indigenous peoples the order and culture wanted by God against their will. They saw the Indians as pagan savages who had to be converted. The latter, however, saw the settlers' advance as an attack on their rights and their economic and cultural foundations. For this reason, the immigrant residents had to reckon with attacks by these savages until Anthony Wayne's victory in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and , something Europeans have become unfamiliar with, have to beware of dangerous and often unknown animals. In this way, Taylor learned early on, as later historians assumed, to deal with threat situations. Although the father was a justice of the peace and a member of the State Legislature and, as a land speculator, soon had considerable estates, Taylor enjoyed little education. He learned to read and write from his mother, as is usual in the sparsely populated “Frontier”. The focus of education was practical training in plantation management and self-sufficiency . Taylor later became a skilled planter and shrewd businessman. In addition to his military career, he earned considerable wealth in the form of real estate in lengthy periods of time off duty. Taylor valued the education of his children.

Military career

Beginning as a young officer

At the latest when the eldest brother William took up service as an artillery officer in February 1807, Taylor's interest in a military career awoke. At the time of his application, the Chesapeake - Leopard affair was in acute danger of war with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland , which is why the United States Army was almost threefold. Because of this enormous growth, Taylor immediately received an officer’s license with a commitment period of five years. In May 1808 he was hired as a first lieutenant in the 7th Infantry Regiment and subsequently developed into a superior who was casual to negligence when it comes to outward appearances such as style and uniform, but led with a strict hand and internalized the craft of war . The regiment was under the command of Colonel William Russell and was just being set up. Taylor was seconded to Washington and Maysville , Kentucky, to recruit volunteers . By April 1809 he had recruited a company and embarked with her to New Orleans to reinforce Brigadier General James Wilkinson 's troops. The health and morale of the soldiers stationed there was in an extremely worrying state because of the disastrous sanitary conditions and the proximity of New Orleans nightlife, which was accompanied by alcoholism and venereal diseases.

Finally, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn ordered the New Orleans withdrawal to Natchez . Nevertheless, Wilkinson moved with his troops in June only about 20 km downstream of the Mississippi to Terre aux Boeufs in what is now St. Bernard Parish . The camp was set up on a swampy plain one meter below the river level and suffered from poor food supplies. In particular, the soldiers from Kentucky, who had previously experienced an extremely cold winter in their homeland, suffered from high mortality. How much Taylor got from this episode is unclear as he was in command of Fort Pickering near Memphis in May and June and his return to New Orleans is in doubt. Tradition has it that he fell ill with yellow fever in Terre aux Boeufs and was released on home leave to recover. His stay in Louisville is guaranteed from September; During this time he met his future wife Margaret Mackall Smith in neighboring Jefferson County . However, he was spared the fate of many of his comrades, nearly half of whom had died, by the time Wilkinson finally reached Natchez in September.

Taylor and Smith were married on June 21, 1810. His wife came from a planter family in Calvert County , Maryland and was a devout episcopalian . Taylor and his wife remained bonded for life. Their first daughter, Ann, was born in April next year. Margaret gave birth to five other children, four of whom reached adulthood. Taylor received 130 hectares of land from his father as a wedding gift, which began his career as a landowner and land speculator. In November of that year he was promoted to captain . When Taylor was ordered to the Indiana Territory in April 1811, the threat of war with Great Britain had subsided, which is why the army was now stationed on the western state border, which at that time formed the Ohio River . It was supposed to protect the settlers against raids by the Indians. The troops were distributed over a chain of many forts , which usually had a crew of around 20 men and two officers. Taylor was entrusted with the command of Fort Knox, which is in what is now Vincennes on the Wabash River . Since his predecessor had been tried in court-martial for having shot and killed a subordinate officer, Taylor's assignment was to restore military order, which he quickly succeeded in doing. In August he made his way to Frederick, Maryland, where he was called as a potential witness in the court martial against Wilkinson. Wilkinson has been charged with his behavior in Terre aux Boeufs and his involvement in the "Burr Conspiracy" . Wilkinson's close ties with Spain, later revealed as treasonous, were also the subject of the negotiation. Before Taylor could be called to the stand, he was acquitted. Thereafter, Taylor returned to Louisville and was again entrusted with the recruiting of volunteers.

British-American War

As part of the preparations for the British-American War , Taylor received the order in April 1812 to lead a company of recruits to Fort Harrison, north of Vincennes on the east bank of the Wabash in what is now Terre Haute . On the march and after arriving at the garrison in early May, the soldiers struggled with illnesses, so that Taylor had less than 20 healthy men in early September. In June President Madison declared war on the UK. The reason for this was not only, as officially announced, the practice of the Royal Navy of forcibly recruiting American sailors, but also that Great Britain incited the Indians against the United States. At the beginning of August Taylor was certain that an attack by Indians was imminent, not least because the British and their allied Tecumseh had conquered several American bases, the most important of which was Detroit , since the beginning of the war . On the morning of September 4th, two scalped settlers were found outside the fort , and in the evening Chief Joseph Lemar approached under a white flag with an entourage of 40 Indians from Winnebago , Kickapoo , Potawatomi and Shawnee and as followers of the “Shawnee Prophet “ Tenskwatawa were recognizable, the base. Lemar asked for food aid to be given to them the next day because his people were threatened with starvation. Taylor quickly recognized a trap, as this was a well-known ruse of the Indians, especially since all these tribes came from the northern Indiana Territory and had fought against Governor William Henry Harrison at the Battle of Tippecanoe the year before .

Shortly before midnight, more than 400 men attacked the fort, setting fire to a log cabin inside the fortification. In this emergency situation, which two soldiers evaded by deserting, Taylor showed leadership by reassuringly reassuring the soldiers with clear commands and coordinating the fire fighting. Then he had a makeshift, man-high parapet erected until dawn to fill the gap in the fortification caused by the fire. In the end, the attack was repulsed, with two soldiers falling. The attackers then withdrew a little, pillaged the surrounding area and surrounded the fort. After a request for help from Governor John Gibson , who learned of the siege, Russell shocked Fort Harrison on September 16. Taylor received great acclaim for the defense of Fort Harrison and was honored in October 1812 by President Madison with the rank of major ; it was the first such award of its kind in the War of 1812. This first American victory in the war halted the advance of the British and their allied Indians in at least Indiana Territory.

Taylor's next employment was as Chief of Staff under General Samuel Hopkins , who used Fort Harrison as a base of operations and deployed extensive militias . A campaign to destroy a Kickapoo settlement on the Illinois River ended in a complete failure in October 1812 because of supply problems and the troops' lack of courage. On another mission in the following month, the troops marched north along the Wabash River to Prophetstown and destroyed some Indian settlements. The Indians resorted to ambushes and avoided open field battles . During this time, Taylor developed a very low opinion of the efficiency of militias and therefore later reluctant to use them. After that, Taylor was on home leave in Louisville and then headed Fort Knox recruiting in the Indiana Territory and Illinois . After an unsuccessful summer campaign under Russell's command, he returned to Vincennes and, in expectation of a longer standing time in Fort Knox, brought the family to join him. The second daughter Sarah Knox was born there. In 1814, American warfare in the west focused on defending the Upper Mississippi Valley. In addition, Taylor was transferred to General Benjamin Howard in the spring , who commanded the troops in the Missouri Territory from St. Louis . Both feared that the British intended to take St. Louis, as they had already conquered the forts in Prairie du Chien and the forts in Rock Island, Illinois , which was at the confluence of the Rock River with the Mississippi. Howard therefore planned to march to the Rock River himself, destroy several Indian settlements there and build a fort on the way back at the confluence of the Des Moines River with the Mississippi. Before leaving, the general fell seriously ill and entrusted Taylor with the operation.

At the end of August 1814 Taylor left St. Louis with a force of 430 men on eight reinforced Keelboats . After a few days the measles broke out, so that many soldiers suffered from severe exhaustion even before they came into contact with the enemy. On September 4, they reached the Rock River, sighted Indians and pitched for the night on a river island near the present Davenport ( Iowa ). They were attacked in the early dawn, but were able to drive the Indians back to Credit Island to the south . Soon they came under shell fire from the western bank of the river from an infantry gun of the British Army , which supported its allies with 30 soldiers. Given this fire support and an inferiority of 1: 3, Taylor ordered the withdrawal after a council of war. Despite the de facto defeat, one of the successes of this undertaking was that no enemy troops were operating south of Credit Island in the future. As directed by Howard, Taylor had a fort built at the confluence of the Des Moines River with the Mississippi. At the end of October he was ordered back to St. Louis before the fortifications were completed, as General Howard had died. In November Russell took command in the Missouri Territory and Taylor returned to Vincennes, where he stayed until the end of the war.

In the fall of 1814, though not extraordinarily ambitious, he was bothered by the fact that his regular rank was still captain. This was related to the practice that promotions were only made within a regiment and not in the army as a whole; Taylor could not be promoted until a corresponding post in his regiment became vacant. He blamed Colonel William P. Anderson for the career stoppage, who harbored a grudge against him since changing an order of his own to order a recruiting officer to assist Governor William Clark in the Missouri Territory. In fact, Anderson had written a series of letters to Secretary of War James Monroe complaining about Taylor. Taylor asked, among others, General Hopkins and Representative Jonathan Jennings to stand up for him. In a letter to Adjutant General Parker, Taylor wrote to inquire about the extent to which complaints from others about his person prevented his promotion. On January 2, 1815, Parker replied that he had a very good reputation in the War Department and informed him of the promotion to major, which came into effect on February 1 . On March 1, 1815, however, in view of the peace of Ghent , the Congress decided to reduce the army from 60,000 to 10,000 men. Taylor was left in active service, but since his regiment was merged with three others, downgraded to the rank of captain. After he had traveled to Washington, DC , tried unsuccessfully on his case and even President Madison's commitment had failed him, he turned down the officer's license on June 9, 1815 and retired in Louisville.

Return to the army and years of routine service

Taylor's initial joy in enjoying life as a family man and planter soon gave way to boredom. When he was offered a vacant major post in the 3rd Infantry Regiment under Colonel John Miller, he accepted and rejoined the Army on May 17, 1816, like his brother. After the birth of his third daughter Octavia Taylor, he reported to General Alexander Macomb in Detroit in late September , who entrusted him with command of Fort Howard on the Fox River in what is now Green Bay from the spring of next year . The military post was of great importance because it formed the north-western end of the "Frontier" at that time, which was mostly populated by French. The massive fort was in a prominent position, with which it should intimidate the still pro-British Indians in the area. At first, Taylor was busy completing the fortress. Because of questions of subordination, there was a falling out between Macomb and Taylor. During this time he made friends with Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Jesup , who became his most important mentor and supporter in the army. In September 1818 Taylor was on leave and returned to Louisville for a year.

There he supervised the recruitment offices of his regiment and was promoted to lieutenant colonel on April 20, 1819 . In June President Monroe and General Andrew Jackson received him for breakfast in Frankfort ; he accompanied the President on a visit from Representative Richard Mentor Johnson . Shortly after the birth of the fourth daughter Margaret Smith, Taylor moved in August 1819 to the 8th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch . In March 1820, he reported to his regiment near the Choctaw tribal area , which was building a military road from the Pearl River to the Gulf Coast to Bay St. Louis, Mississippi . The family meanwhile lived with his wife's sister in St. Francisville , Louisiana . There Margaret and her four daughters fell ill with malaria . In September 1820, Taylor, who had meanwhile completed the construction project, learned of the death of their two youngest daughters. The next year he moved to the 7th Infantry Regiment and built Fort Selden in November against the backdrop of the Adams-Onís Treaty on the newly drawn southwest border near Natchitoches , which was replaced the following year by the stronger Fort Jesup .

Until 1832, other typical commands for the routine service of an army officer in the "Frontier" followed: He was stationed in Baton Rouge from October 1821 to March 1824 and then until December 1826 stage manager in personnel recruitment in the western military district, where he spent most of the time in Louisville the family could spend. During this usage, daughter Mary Elizabeth and son Richard were born. He then served as garrison commander in New Orleans until May 1828 . Until July 1829 he was in command of Fort Snelling and then that of Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien. As everywhere in the army prior to the Depression of 1837 , Taylor faced low-skilled recruits, often immigrants. As the commander of Fort Crawford, he regularly complained about the widespread alcoholism and desertions in the crew. From July 1830 he was on home leave for a long time and for a short time in Baton Rouge and New Orleans until he was ordered to his annoyance back to Fort Crawford in the fall of 1831, which he delayed as long as possible. Not until May 1832 did he arrive at Fort Armstrong , where he succeeded Colonel Morgan, who had recently died, as commander of the 1st Infantry Regiment.

Black Hawk War

From May 8, 1832 Taylor commanded the reinforced 1st Infantry Regiment in the three-month Black Hawk War . The background to the conflict was the increasing penetration of white settlers into the territory of the Sauk and Winnebago. From the spring of 1831 a significant part of the Sauk living in northern Illinois and northwest of Rock Island began to fight against their displacement under the leadership of Chief Black Hawk . The cause of the war was Black Hawk's decision in April 1832 to reclaim land east of the Mississippi that General Edmund P. Gaines had taken from them the previous year. To do this, he crossed the river with several hundred Indians, most of them women and children, and moved - encouraged by the hesitation of Brevet Brigadier General Henry K. Atkinson, strongly criticized by Taylor - along the Rock River northeast. When Governor John Reynolds finally got Atkinson to act, Taylor ordered Taylor and his troops in Dixon to join a larger militia association and pursue Black Hawk from there. After his trail was lost, Taylor stayed in Dixon and built a fort there as a base of operations for further searches.

At one point, a militiaman who was covered by his officer refused to give orders, which heightened Taylor's reservations about the people's army. On July 26, 1832, Taylor began pursuing the now-tracked and retreating Black Hawk. On August 1st, he was arrested at the confluence of the Bad Ax River with the Mississippi, and the next day his armed forces were almost completely wiped out in what was more like a massacre, as they awaited hostile Sioux on the supposedly saving western bank of the Mississippi . Taylor arrived on the battlefield very late and played no decisive role. Black Hawk was captured on August 25th and interned at Fort Crawford, where Taylor had now taken command. In early September, the two officers Robert Anderson and Jefferson Davis transferred him to the care of General Winfield Scott .

For Taylor, the love affair that developed from 1832 between the second oldest daughter and his adjutant Davis was far more momentous than the Black Hawk War . He was against a wedding because he did not want any of his daughters married to an officer in order to spare them the associated privations in family life. Soon a great personal dislike developed between Davis and Taylor. Since Davis was banned from Taylor's quarters, the couple had to plan their meetings carefully. The situation eased from March 1833, because Davis was transferred to a dragoon regiment for two years , which did not affect their intensive correspondence. When Davis' application for discharge from the army for late June 1835 was approved, he married Sarah Knox on June 17, 1835 without the consent of the father in the house of an aunt of the bride near Louisville. When Taylor found out about this, he accepted it and held no grudge against them. The honeymoon took the couple downstream from the Mississippi to see an older brother of Davis. There they both became infected with malaria in August, of which Sarah died on September 15. That loss was the greatest tragedy in Taylor's life.

Second Seminole War

After the Black Hawk War, Taylor was stationed at Fort Crawford until the summer of 1837. There his task was, among other things, to protect the Indian territory on the other side of the Mississippi from invading miners and the import of alcohol, whereby he worked closely with the Bureau of Indian Affairs . In the summer of 1835 he and his garrison supported a road construction project east of today's Portages over a distance of about 170 kilometers. From November 1836 he was deployed for a few months in the western district command near St. Louis. In this phase before the economic crisis of 1837, as a planter, he recorded the greatest gains through land speculation and cotton cultivation . After the first infantry regiment had been commanded to the southwest border in June 1837, the War Department changed plans shortly thereafter and sent it to the Florida Territory . The reason was that Commander-in-Chief Jesup did not succeed there in ending the Second Seminole War . On the contrary, he fueled the conflict by the insidious capture of Chief Osceola , who wanted to negotiate an armistice under a white flag, in October 1837, especially since Osceola died in custody under questionable circumstances just a month later.

This war was one of the most expensive, disillusioning, and neglected of all the United States Army's military confrontations with the Indians. This was less due to the fighting strength of the Seminoles , but rather to the skill with which they exploited the terrain and were able to evade the enemy. Taylor landed at Fort Brooke , Tampa Bay in mid-November and had about 1,400 men under his command, including regular soldiers from two infantry regiments, militias from Missouri and allied Indians of the Lenni Lenape and Shawnee Indians . He received southern Florida between the Kissimmee River and Everglades as the area of operation . Jesup ordered him to go deep into the Seminole area and then march along the Kissimmee River towards Lake Okeecho . In doing so, he was supposed to destroy all Seminole forces he encountered. At the beginning of December they reached the headwaters of the Kissimmee and built Fort Gardiner there, before marching south on the west bank of the river. Taylor hired a few Seminole warriors and interned them in forts. Among them was Ote Emathla, known to the whites as "Springer" and one of the leaders of the Dade massacre on December 28, 1835, in which two army companies with more than a hundred men were completely destroyed.

On Christmas Day 1837 Taylor came across a defensive position of the Seminoles on Lake Okeechobee. This was one of the rare occasions when they resorted to such a defensive tactic. The 380 to 480 Seminoles set up the battle line, hidden by palm trees and tall grass, behind a swamp that was less than a meter deep. Their weakness was that they consisted of three different groups, each of which had its own guide with "Alligator", "Wildcat" and Sam Jones and operated independently of one another. Taylor's tactical inventiveness was limited and showed a penchant for frontal attacks. Shortly after noon he therefore sent a squad of Missouri militiamen, the most inexperienced men, to the front to skirmish against the protests of their unit leader Richard Gentry . Perhaps he did this because he saw them, because of their impulsiveness and disorganization, as a suitable first wave of attack against an opponent who was also fighting with little discipline. But this decision probably speaks of Taylor's disdain for militias. In the second line, members of the 4th and 6th Infantry Regiments followed, while Taylor retained the strongest unit, the 1st Infantry Regiment, as a reserve. He also sent two mounted companies to bypass the enemy's left wing. The Seminoles let the militias move close to their position until they opened fire. When Gentry fell, their line dissolved. In the second line the 6th Infantry Regiment on the right wing suffered great losses; almost all of the officers in this unit fell. On the left wing, however, the Seminoles quickly retreated after weak resistance. When the mounted companies grabbed the Seminoles on their left side, Taylor threw the regiment held in reserve into action, which was ultimately able to throw the Seminoles out of their position with a bayonet attack on the right wing. After a fighting time of two and a half hours Taylor had won a Pyrrhic victory with 26 dead and over a hundred wounded , since the Seminoles could evade further pursuit with significantly lower losses and so no strategic progress was made. It remained the only open field battle in the Second Seminole War. She earned Taylor great recognition and the rank of brigadier general.

More serious was the psychological impact of the Battle of Okeechobee , which received a lot of attention. A controversy arose between Taylor and Missouri: while the latter accused the Missouri militia, which had almost no casualties to complain about except for Gentry, cowardice in front of the enemy, the Missouri public blamed him for sacrificing the militia to get the regular troops to protect. The Missouris State Legislature passed specific charges against Taylor. War Secretary Joel Roberts Poinsett gave him full backing and prevented a committee of inquiry into the matter. The Battle of Okeechobee earned Taylor the nickname "Old Rough and Ready" (German: "Altes Raubein"), as he and his men waded through the swamp towards the enemy position in the course of the battle. Further searches in the Everglades were unsuccessful, which is why Taylor limited himself to keeping the Seminoles from populated regions. In the spring of 1838 "Alligator" surrendered with hundreds of followers. In May, Taylor received the supreme command of the Florida Territory, succeeding Jesup, and planned in a war of attrition to push the Seminoles southeast of a line from St. Augustine to Tampa Bay and thus cut off their supplies. The opponents eluded this plan with success and when Taylor wanted to use sniffer dogs to search , this sparked protests in Congress. Another campaign in the winter of 1838/39 with over 3500 soldiers was ineffective against the guerrilla tactics of the Seminoles. He now developed the so-called "squares" (German: "squares") plan, which divided the territory in question into square districts of equal size, each with a side length of 32 km. A centrally located military post should control each of these districts. This approach, which the Americans repeated in the Vietnam War and the Filipino-American War , was likely to be promising in the long term , was too passive for the residents of Florida, so that in March 1839 Major General Macomb was sent there. He tried to find a diplomatic solution without success. After another fruitless winter campaign, Taylor asked for his replacement in February 1840 and left the Florida Territory in May.

Afterwards Taylor was on home leave and then used for several months in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, so that he could oversee the cotton plantations he had owned in Louisiana since 1823. When his former British-American War superior William Henry Harrison moved into the White House , Taylor showed an unprecedented political interest. In a letter to the new president, he complained about the “corruption” and “unsuitability” of the predecessors Jackson and Martin Van Buren . Since Harrison died shortly after the inauguration , the correspondence was without consequence. It was the first time Taylor identified himself as a supporter of the United States Whig Party .

From June 1841 he served at Fort Gibson as the commander of the Second Military District, which included Indian territory . The fort, which was notorious for its disease-causing conditions and which was later replaced as headquarters by Fort Smith , served as the end of the path of tears : the Indians expelled as part of the American Indian policy were deported to this point. From Fort Gibson they were then distributed to Indian territory. Under Taylor's command, the forts Washita and Scott were built in Indian territory. When the threat of war between the Republic of Texas and Mexico was acute, he stopped the Indians from taking advantage of the opportunity to raid Texas. To this end, he attended two large council meetings of the Plains Indians in 1842 and 1843 . During these years he sold three plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana and acquired the nearly 800 hectare Cypress Grove plantation north of Natchez, including 80 slaves, as a new family home. The few surviving testimonies in this context indicate that Taylor treated his slaves comparatively well and paid attention to their health and nutrition.

Mexican-American War

From Fort Jesup to Matamoros

In April 1844, Taylor became the commander of the First Military District, with Fort Jesup as its headquarters, which was only separated from the Republic of Texas by the Sabine River . Linked to this was the command of the core of a corps that had yet to be formed . The task of Taylor's so-called "Army of Observation" ("Observation Army") was the protection of Texas, which was debating whether to join the Union as a state, against Mexican intervention. At the heart of the conflict were the border issues controversial between Mexico and Texas . While Mexico viewed the Nueces River as a border, Texas claimed territory that extended over 200 km further to the Rio Grande . Despite the reservations of Texas President Sam Houston , a clear majority in favor of the annexation, viewed with great reluctance by Mexico, was foreseeable and the danger of war was correspondingly high. Therefore, Taylor was ready to immediately protect the western border of Texas, should the American ambassador to Texas, Andrew Jackson Donelson , request him. When President John Tyler did not get the annexation through the Senate in June 1844 , the pressure on the "observation army" did not ease. Early next year, Taylor accidentally met ex-son-in-law Davis. The two developed a very close relationship, despite considerable political differences of opinion. When, just a few days before James K. Polk's inauguration, the Anschluss of Texas was finally adopted, the next hurdle was a convention in Texas on July 4, 1845. Donelson urged the Texans at the end of June to officially seek protection from the "observation army" to ask. This was entirely in the spirit of Polk, because although public opinion and most of Taylor's officers were against meddling in this border dispute, he was on the side of the Texans. According to George Gordon Meade , a lieutenant in the "Observation Army" at the time, Taylor himself opposed the annexation of Texas to the United States. Taylor chose Corpus Christi , located on the south bank of the Nueces River, as a field camp and received strict orders from Secretary of War William L. Marcy to refrain from any hostility towards the Mexican army.

In mid-August 1845 Taylor reached the south bank of the Nueces River with the 3rd Infantry Regiment and began building a field camp. Soon the troop strength in Corpus Christi was well over 4,000 men, which made up almost half of the entire army. When the 2nd Dragoon Regiment under the leadership of David Twiggs approached the camp on an alternative route across the inland, Taylor decided to ride towards it with only a few men in order to meet it in San Patricio . Rides of this kind were typical for Taylor and the exception for officers of his rank. As Polk continued to attempt to sell part of the disputed territory known as the "American Southwest" and Upper California despite Mexico's refusal , the "Observation Army " stayed in Corpus Christi longer than expected. Soon Taylor renamed his armed forces in the "Army of Occupation" ("Occupation Army"). He used the time and planned extensive maneuvers for the units , as his troops had only had operational experience at company level so far.

From this period of calm before the war, some personal observations of contemporary witnesses about Taylor's character have come down to us, which emphasize his casual demeanor and the fact that he almost never wore a proper uniform. As the waiting time dragged on into late autumn, the morale of the "Army of Occupation" sank, to which the amusement arcades and brothels that were quickly emerging around the camp contributed their part. There were also attacks by members of the army against Mexicans living near the camp. After a special incident, Taylor ordered an army rally to restore discipline. A dispute broke out between Colonels William J. Worth and Twiggs over who should show the troops in Taylor for the occasion . Taylor chose Twiggs, who had a senior position but not a brigadier general like Worth. This dispute split the entire army and had Colonel Ethan A. Hitchcock send a letter of appeal in the form of a robin to the Senate to protest the decision. Disgusted by this development, Taylor then canceled the army show.

After the Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera had refused in December 1845 to receive the American negotiator John Slidell , the latter returned. Polk was determined to go to war after this affront and ordered Taylor to go to the Rio Grande, that is, to the farthest edge of the territory claimed by Texas, thereby delegating the responsibility for war and peace to the level of field commanders. Taylor, who now had three infantry brigades and, true to his reluctance to refrain from the possible reinforcement by militias, decided to take the land route to Heroica Matamoros , while supplies and equipment were to be transported by sea. When Marcy failed to escort him through the American fleet , he won Commodore David Conner and the Home Squadron under his command as support in the form of two gunboats . On March 1, the vanguard left Corpus Christi. As expected, Taylor encountered no resistance until reaching the Arroyo Colorado . A cavalry unit of the Mexican army that appeared to be ready to fight was in position on the south bank of the river . Before the third brigade arrived, Taylor dared an attack led by Brevet-General Worth. When they reached the other bank, however, they found that the Mexicans had withdrawn. Taylor then rode with a dragoon regiment to Port Isabel to secure it for supplies, and let the rest of the army set up camp just outside Matamoros in Palo Alto . The supply ship and the two gunboats had already arrived in Port Isabel, so Taylor entrusted officer John Munroe with command of the supply base and returned to the main force. On March 28, this took a favorable position on the north bank of the Rio Grandes opposite Matamoros. Before leaving Corpus Christi, Taylor had issued strict orders to respect the rights of Mexican citizens. While the army still adhered to the standard in this phase, attacks on the civilian population later became a serious problem after crossing the Rio Grandes, which Taylor could no longer control.

On the day of their arrival there was little sense of hostility, so the soldiers could swim in the river undisturbed. Taylor dispatched Worth that afternoon to negotiate with General Francisco Mejia, Mexico . This refused to speak to anyone other than Taylor himself and let his deputy conduct the discussions with Worth, which led to no result. The Mexicans demanded the withdrawal of the Army of Occupation and refused Worth a visit to the American consul in Matamoros. Tensions rose rapidly thereafter. Before dark, the Mexican army erected a parapet and brought a 12-pounder cannon into position to coat the American camp that was called Fort Texas . A few days later, Worth learned that the President had decided against him in his dispute with Twiggs, whereupon he submitted his farewell to Taylor and started walking home. The Army of Occupation's biggest problem at the time was desertion, which worsened when two dragoons arriving at Heroica Matamoros were treated there as guests of honor. There were many foreigners in the army, especially Germans and Irish , whose patriotism was often low as they had been denied full citizenship. The Catholic Irish in particular showed themselves to be prone to desertion, as they were lured by the Catholicism of Mexico. In mid-April, two officers were found dead outside the camp. The separatist politician and general Antonio Canales Rosillo , who had deserted from the Mexican army, was probably responsible for her death . The situation worsened at the end of April when General Mejia was replaced by Mariano Arista , who was leading a force of more than 3,000 men and was tasked with destroying Taylor's army. On April 25, a strong Aristas cavalry unit ambushed north of the Rio Grande and captured an Army of Occupation patrol, killing 11 Americans. This was the hoped-for cause of war, and Taylor reported to the President that "the hostilities may now be considered to have begun".

On May 8, Polk convened his cabinet to discuss how to proceed in the Mexican case. The news from Taylor had not yet reached him at this point. Meanwhile, the envoy Slidell had arrived from Mexico, whose rejection by Herrera was viewed by the president as a national insult that justified a war. In addition, the border dispute with Great Britain in the Pacific Northwest calmed down at this time , as Secretary of State James Buchanan was on the verge of reaching an agreement that included the 49th parallel as the border between the province of Canada and the United States . Because of this relaxation in the Oregon Boundary Dispute , Polk saw the danger of a two-front war with Great Britain and Mexico as extremely low. In the cabinet, only Buchanan and Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft voted against a war with Mexico. When Taylor received news of the outbreak of hostilities the next evening, he made a declaration of war in front of Congress two days later, on May 11th . The reason given was that "American blood had been shed on American soil," with Polk subtly blaming Taylor for the precarious situation of the Army of Occupation. Polk's declaration of war received an overwhelming majority in Congress; only John C. Calhoun and Thomas Hart Benton appeared as prominent opponents . The Capitol approved the drafting of a volunteer army of up to 50,000 men. This majority did not reflect enthusiasm for the war, but merely the perceived patriotic obligation to rescue the endangered Taylor army. Large sections of the population felt that President Polk had been manipulatively driven into the Mexican-American War against their will .

The battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma

Taylor's position on the Rio Grande was visibly endangered, which is why he only held the position to await the reinforcement that had meanwhile been requested. The problem was that the Americans were spread across Fort Texas and Port Isabel, just under 50 km away. When Taylor had adequately fortified the fort and secured it with a crew of almost 500 men, he moved to Port Isabel on May 1st, as he was expecting an attack by the Mexican generals Arista and Pedro de Ampudia , who were crossing the Rio Grande with two brigades. Shortly after Taylor's departure, Ampudia began bombarding Fort Texas, but it held out. After reinforcements arrived from home and Taylor Port Isabel was well defended, he marched back to Matamoros on May 7th. The following day around noon he encountered Arista's infantry near Palo Alto, which were soon reinforced by the arriving troops of Ampudia. In total, Arista commanded almost 3300 men, which meant that the Army of Occupation in the Battle of Palo Alto was outnumbered by a ratio of 1: 2.

Taylor positioned the heavy artillery made up of 18 pounder cannons in the center and scattered four light batteries between his five infantry regiments . In order to protect the convoy from Port Isabel on his right flank , he used a new type of mobile artillery piece that was far superior to the Mexican cannons in terms of range, accuracy and explosive power. Taylor followed the battle chewing tobacco on his horse "Old Whitey". Thanks to the superior artillery, two cavalry attacks by General Anastasio Torrejón on the train were repulsed. When a fire broke out in the chaparral and the development of smoke significantly reduced visibility, the guns were silent for an hour. This was followed by two more unsuccessful cavalry attacks by the Mexicans, whose right wing was on the verge of collapse under shell fire. When the Mexican artillery ran out of ammunition, Arista withdrew his troops in the early evening to a plateau immediately adjacent to the battlefield. Although the Mexican army had suffered far more serious losses with 92 dead than the "Army of Occupation" with nine dead, Arista continued to hold a strong position. The effect of the battle was less tactical than psychological. With the experience of the Indian Wars, Taylor had previously given little value to artillery, but now recognized its clout. Tragically, Major Ringgold, who had played a major role in the practical development of mobile artillery, was among the fallen. The battle of Palo Alto had a very negative effect on the morale of Arista's troops, who had been helpless to face the devastating effects of the artillery.

In the early morning of the following day, Arista and his army retreated towards Matamoros and took up a new position almost 10 km behind Palo Alto at a dried up arm of the Rio Grandes called Resaca de la Palma. In doing so, he distributed his troops so widely that their numerical superiority was largely insignificant. Against the majority of his staff, Taylor ordered the pursuit of Aristas. When Taylor reached Resaca de la Palma in the early afternoon, he again hoped to be able to play the superiority of the artillery decisively, which was prevented by the densely overgrown chaparral, which significantly restricted visibility. Therefore, Taylor concentrated the attack on the Matamoros road, which was held by a Mexican battery. A dragoon unit under Captain Charles May led the attack, was able to take the battery position and take some prisoners, but was quickly thrown back by Mexican infantry. On the other side of the battlefield, the mobile artillery fought off a cavalry attack from Torrejón. After May's failure, Taylor ordered Colonel William G. Belknap with the 8th Infantry Regiment to take and hold the Mexican battery, which the latter was able to implement and also to take General Rómulo Díaz de la Vega prisoner. When the remaining lines of the Mexicans saw the loss of this central point of their position, they collapsed and fled in complete disorder across the Rio Grande, many of them drowning. Taylor estimated the number of deaths on the Mexican side at 300, while Arista officially put it at 154. The Army of Occupation mourned 49 dead. Typically Taylor refrained from energetic pursuit of the defeated opponent. In Matamoros he learned that the commandant Jacob Brown had been killed in the siege of Fort Texas , but that the defenders had suffered few losses. He ordered the fortification to be renamed Fort Brown .

After he had rejected a ceasefire offer by Aristas on May 17th and this let his ultimatum expire, the “Army of Occupation” crossed the river the next day and found Matamoros deserted. For the next few months, Taylor took over the city administration, treating the population economically generously and not interfering in their affairs. During this time, his staff was reinforced by several, all democratic and mostly capable generals. Among these were William Orlando Butler and John A. Quitman ; besides, Worth had returned. News of Taylor's victory reached Polk on May 23, 1846 and threw the president into a dilemma. As a Democrat , he the one hand begrudged Whig generals like Scott, John E. Wool and Taylor political triumph in the field, on the other hand he was allowed this as commander in chief does not openly show. In the case of Taylor, the enthusiasm for his success was as great as that after Jackson's victory in the Battle of New Orleans , so that there was general demand for him to remain as Commander of the Army of Occupation and Polk awarded him the rank of Major General. The president continued to give Taylor a free hand, except for a vague order not to “remain completely on the defensive”. He had already read from the subtext of the previous orders that Washington wanted an invasion of Mexico. Marcy and a short time later Polk asked Taylor to examine whether he could advance to Mexico City , which he strongly advised against and instead suggested the conquest of the border provinces with San Luis Potosí as the end point. They also demanded that he only accept ceasefire offers if they were meant "sufficiently official and sincere," that is, if they amounted to a surrender . Taylor intended to take Matamoros and then advance further west on Monterrey . Through military reconnaissance he knew that the direct route to Monterrey had failed due to insufficient water supply, which is why the route along the Rio Grandes to Camargo had to be made to cross the river there. For the protection of the supply base against the Mexican Navy, he coordinated with Conner, the only time during the Mexican-American War he dressed in a service suit that was appropriate to his rank. Taylor faced the difficulty of handling the influx of volunteers. The sanitary conditions in the camp became more and more difficult, so that more dysentery occurred. The strong anti-Catholicism of the volunteers worsened the relationship with the local population to such an extent that Catholic military chaplains were finally appointed.

The Battle of Monterrey

After steamships arrived as a means of transport, the Army of Occupation moved to Camargo from the beginning of July, where Taylor arrived at the beginning of August. The army camped near the confluence of the Río San Juan into the Rio Grande. In the camp, there were dramatic differences between the regular soldiers and the inexperienced volunteers, which was particularly evident in hygiene and discipline. In connection with the humidity and heat caused by the location, this led to an eighth of the men, almost all of them volunteers, dying of disease. At home, the public pressure on Taylor to continue the campaign grew, so that he marched with three divisions against Monterrey from mid-August . On the morning of September 15, the vanguard came to the small town of Marín , about 40 km from Monterrey, near which Taylor gathered his entire armed forces, which numbered over 7,200 men, in anticipation of a decisive battle for the heavily fortified Monterrey over the next three days . Pioneers identified the Independencia Hill with the Episcopal Palace as the key to victory. During the attack, Taylor had to take into account an unfinished cathedral building north of Monterrey, which was heavily fortified by the Mexicans and called the “Black Fort” by the Americans.

The American battle plan was complex and probably too ambitious to originate from the conservative Taylor. A division under the command of Worth took the Independencia from the south on September 21, the first day of the Battle of Monterrey, and cut off supplies. The diversionary maneuver by the rest of the army on the city east of the "Black Fort" did not go as planned, so that the Americans suffered heavy losses and remained inactive the following day. On September 23, the Butlers and Wiggs' divisions, along with Wood, successfully resumed their attack. The following day Ampudia and Taylor signed a ceasefire agreement. The Mexicans withdrew behind a line from Linares to Parras de la Fuente , while Taylor did not pursue the Mexican army for eight weeks. Contrary to the order from Washington, he accepted the offer in view of the exhaustion and supply situation of the army. Polk reacted angrily to the news while the public celebrated Taylor again. Polk made a good face to bad game and promoted Taylor to regular major general with appropriate service. He called on Taylor to breach the contract and pursue the Mexicans immediately. This order did not reach him until a few days before the end of the agreement. Taylor found himself increasingly embroiled in a two-front war with Mexico and the Polk administration; Scott reinforced his distrust of Washington. In Monterrey in particular the Texan volunteers raged against the civilian population until, to Taylor's relief, their regiments under James Pinckney Henderson were withdrawn.

The Battle of Buena Vista

Despite the defeats, Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna was unwilling to make territorial concessions to Polk. The White House therefore secured the conquered territories for the time being, which included Monterrey, among others, the Republic of California , and waited for Mexico to react. When the original war opponent and influential Senator Benton spoke out against this strategy and demanded an invasion of Veracruz and the capture of Mexico City , Polk immediately agreed and reluctantly entrusted Scott as general-in-chief with the supreme command. Taylor had in the meantime tried to secure a military line that ran from Saltillo via Monterrey to Tampico , which served as a supply base. In the midst of this project, Taylor received the "proposal" from the Secretary of War to let go of Saltillo and massage the Army of Occupation in Monterrey. Since the message was not explicitly formulated as an order and he was becoming increasingly hostile to the government, Taylor ignored the communication and took Saltillo and Tampico in mid-November without a fight. Scott arrived in Camargo around Christmas and, in Taylor's absence, summarily requisitioned all the local divisions for his expeditionary army to Vera Cruz. Taylor, who until then had been on friendly terms with Scott, reacted with indignation and saw it as an attempt to persuade him to give up his command. He was left with almost nothing but volunteer regiments and Butler and Wool as commanders. Nevertheless, he viewed the well-trained army of almost 20,000 men that Santa Anna gathered in San Luis Potosí in January 1847 without much concern, since there were over 320 km and a desert between it and Saltillo. Santa Anna was not deterred, however, underestimating the privations of the desert and losing a quarter of his army in three weeks on the march to Saltillo.

After Wool informed him of the approach of Santa Anna at the end of January, Taylor concentrated his armed forces of almost 5,000 men, which had in the meantime been reinforced with a regiment from Mississippi under the leadership of Davis, on February 21, 1847 in a place south of the hacienda de Buena Vista, which was known as the "bottleneck" and whose terrain favored a defensive position. A request from Santa Anna to surrender Taylor declined on the morning of February 22nd. The battle began in the early afternoon with a diversionary attack on the Americans' right wing and a Mexican encirclement maneuver on the left wing, which was halted until evening. In the morning the fighting flared up with another Mexican diversionary attack in the "bottleneck", which was repulsed. An inexperienced regiment was wiped out on Taylor's left wing, but a line could be kept parallel to the road. When two Mexican divisions swayed under artillery fire, the Americans counterattacked.

In the morning the division of Francisco Pachecos on the left wing of the Americans was repulsed by two regiments from an inverted V formation and collapsed, which marked the turning point of the battle. A final attack Santa Anna decided to add hurrying batteries of captains Braxton Bragg and Thomas W. Sherman by grapeshot , after which the Mexicans withdrew. Taylor's army had lost nearly 700 men by the end of the day; among the fallen were the son of Henry Clay and the governor Archibald Yell . The Mexican army lost nearly 3,500 men and retreated overnight. Home made Taylor's victory in this David -gegen- Goliat -Gefecht out of it overnight a national hero . With this prestige he found himself on an unstoppable road to political success.

Taylor then moved his force to Saltillo and later Monterrey, where he divided two regiments to protect the road between Monterrey and Saltillo against Mexican cavalry operating behind the lines. Since Taylor was unable to control his force's assaults against the civilian population, with the Texas Rangers being the worst, massacring 24 Mexicans on March 28, many Mexicans supported guerrilla operations. Relations with Polk became even more hostile as Taylor accused the White House of withholding reinforcements because it feared him as a potential Whigs presidential candidate. He was allowed an advance on San Luis Potosí, but when the volunteer commitment expired in May, he was doomed to inactivity. In July, a large part of the remaining "Army of Occupation" Scott was assigned to reinforce the campaign against Mexico City . Frustrated like most of the rest of his armed forces, Taylor asked for a six-month home vacation in October shortly after Scott's capture of Mexico City , which for some time outshone his own fame. In early December he arrived in New Orleans, where his arrival was celebrated as a major event. A few days later he was in Cypress Grove and his career as field commander came to an end. The biographer K. Jack Bauer sees Taylor's reputation as a great military leader as undeserved, since his success was essentially based on the fact that the enemy commanders had even less tactical skills than he. In addition, he benefited from excellently trained and self-confident subordinates and lacked the instinct in the field to secure a complete victory with devastating blows.

Presidential election 1848

When Taylor decided to run for president in 1848 cannot be precisely determined. The political antipathy towards Scott and Polk did not necessarily go hand in hand with ambitions of its own. Shortly before the Battle of Buena Vista, he explicitly denied having any. In the summer of 1846, the party leader of the New York Whigs Thurlow Weed wooed him and the first non-partisan meetings named him as a "candidate of the people". In December of this year, Congressman Alexander Hamilton Stephens founded with other young Whigs, who were known as "Young Indians" (German: "Young Indians"), a subsequently rapidly growing Taylor Club, which also included Abraham Lincoln , Robert Augustus Toombs and Truman Smith belonged to. Within the party, the wing of the radical abolitionists , i.e. the opponents of slavery, resisted this enthusiasm for Taylor . They wanted to enforce the Wilmot Proviso to curb slavery as an electoral program and not have a slave owner in the White House. Taylor's political mentor and supporter was his old friend, Senator John J. Crittenden from Kentucky, who was considered a kingmaker within the Whigs. Since the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, he corresponded with Scott and Taylor, who freely shared their feelings with him in correspondence, and assessed their suitability for presidential candidates. When Scott's letters later reached the public in which, full of self-pity and his nickname "old Fuss and Feathers" (German: "old busybody"), he demanded that the Secretary of War should relieve Taylor from his field command, he had disavowed himself so much, that Crittenden excluded him as a presidential candidate. In addition to the victory of Buena Vista, which made him the leading of all possible presidential candidates, it was above all this developing political alliance with Crittenden from July 1846 that brought Taylor into the White House. For the Whigs, in turn, Taylor's war fame was very beneficial because they could whitewash their opposition to the Mexican-American War.

After Buena Vista, Taylor initially denied his ambitions for the presidency, because as long as he was still on active service in Mexico, he saw it as his military duty not to expose himself politically. He frankly admitted that he had never voted in his life. Nevertheless, in 1847, more and more public gatherings voted him the “candidate of the people”. As hostility against the Polk government grew, his opposition to running for office steadily declined. When he expressed himself in a letter to the editor in May 1847 so misleadingly that it could be taken as approval of the Wilmot Proviso, he lost many Southern Whigs in the following and Crittenden advised him against further political expressions. From August 1847, Taylor signaled his readiness to run in the presidential election if a non-partisan organization and not an established party nominated him. In personal conversations and correspondence, however, he was willing to disclose his political positions and identified himself as a follower of Thomas Jefferson's principles . In domestic affairs, he was convinced that sovereignty should lie with the legislature , while the field of foreign policy, as provided for in the constitution, should be reserved for the president. He believed the restoration of the Second Bank of the United States was not feasible and was an opponent of protective tariffs . Unlike most southerners, he advocated public works and opposed the expansion of slavery to new states. Taylor sometimes showed very good analytical skills for a layman; so he correctly predicted the secession of an abolitionist wing from the Northern Democrats. When Clay announced his candidacy in November 1847, Taylor saw his chances of victory waning, but found courage with his triumphant reception after returning from Mexico. He therefore explicitly assured Crittenden that he would maintain his candidacy. When Clay's momentum waned in early 1848, Taylor emerged as the favorite for the nomination, although his continued refusal to support the Whigs met with amazement within the party.

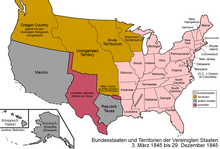

The election year 1848 was marked by turbulent political disputes over whether the new territories should be accepted into the Union as slave states or as free federal states. While the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had been able to calm the slavery conflict between Northern and Southern states sufficiently, the annexation of Texas threatened the regional equilibrium in the Senate and the House of Representatives, especially since the New- Mexico and the Utah Territories and the Republic of California were also up for membership. Overall, the Whigs in the northern states were more abolitionist than the democrats there, while in the Upland South , where their party stronghold was, and in the Deep South , they advocated slavery less than democratic competition. With no national consensus emerging in the north-south conflict, it was advantageous for Democrats and Whigs to remain vague on this point. Taylor had gained a motley following since 1846, which consisted of Whigs and Democrats from the North and South; so it came about that Simon Cameron proposed him as a presidential candidate at the Pennsylvania Democratic Congress . Even the anti-migration nativists campaigned for him as a top candidate.

In April 1848, Taylor's advisors finally decided that his choice had to be backed up by a commitment to the Whig program. When he continued to deny party membership in letters, Weed and Crittenden sent messengers to Taylor in mid-April 1848, including his former adjutant general William Wallace Smith Bliss . They presented him with a draft statement declaring himself Whig and taking up Taylor's remark that he would be president of the people and of a party. The document also contained a promise that the presidential veto would only be used if Congress had clearly broken the constitution . This "First Allison Letter" convinced those among the Whigs who had previously doubted Taylor's political orientation, so that by the end of May he was widely counted as a presidential candidate. The Whigs' nomination convention , the Whig National Convention , met from June 7th in Philadelphia . As was customary at the time, as one of the candidates he was not present at the nomination party conference.

Among the potential Whigs candidates, Taylor had only three to fear in the presidential primaries: Clay, Scott and Horace Greeley . Clay was 71 years old, politically experienced and had already lost three presidential elections. His disadvantage was that he had been a spokesman against the Mexican-American War, but the Whigs had to win over at least some states that had approved the invasion to win the election. General Scott was at first sight better suited than Taylor because of his victories as Commander-in-Chief in the same war and as a West Point graduate, but in addition to his "Old-Fuss-and-Feathers" image, an investigative committee, the Polk against him, damaged him scheduled for his warfare in Mexico. Although the latter acquitted him of all allegations, this process cost him valuable time in preparation for his election campaign. In addition, Taylor had made a name for himself well before Scott with the slaughter successes on the Rio Grande in May 1846. Greeley was a staunch abolitionist, influential editor of the New York Tribune, and a leader in the radical wing of the Northern Whigs. He could not prevail, as many Whigs in the northern states rejected slavery, but believed they had better prospects of victory with a moderate candidate. Weed established itself as the driving force within this faction and alongside Crittenden's most important supporter.

Crittenden was the Taylor camp leader at the Whig National Convention . He thought a victory was possible in the first vote, although the presidium was controlled by supporters of Clay. Since Crittenden had no doubt about Taylor's eventual victory, he initially let the independent delegates and states with hopeless country children as candidates have their way. In the first round Daniel Webster and John Middleton Clayton were placed next to Taylor, Scott and Clay . In the first vote, Taylor received the most votes but missed an absolute majority . He won from ballot to ballot until he secured the nomination in the fourth round with 171 of 283 votes. His victory was a southern triumph, according to Bauer, because most of his votes and key campaigners came from south of the Mason-Dixon Line . This triumph marked the end of an enterprise that began as a campaign of revenge against the Polk administration and Scott. Among the Northern Whigs, this result led to the secession of a group known as the "Conscience Whigs" which Taylor rejected because he was not clearly against the expansion of slavery. When Taylor's Running Mate was nominated , several names were mentioned, under which the experienced and nationwide relatively well-known Millard Fillmore was able to assert himself as a vice-presidential candidate. Taylor, meanwhile, was still in charge of the "Western Command" (German: "Westliches Kommando"), whose management staff he had set up in the immediate vicinity of his plantation. There the official notification of his nomination did not reach him until weeks later due to a misunderstanding. The Democrats held their National Convention in Baltimore in late May . Polk dropped out because he had ruled out a second term for himself. In a highly polarized debate, Senator Lewis Cass and General William O. Butler, who was supposed to counter Taylor's military fame, won a respectable but colorless duo. Originally from the East Coast Establishment of New Hampshire , Cass represented the principle of popular sovereignty first formulated by Vice President George M. Dallas , i.e. the right of the people in the territories to determine the legitimacy of slavery, which invalidates the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Wilmot Proviso was bypassed. In doing so, he presented the party with an acid test; In particular in the free states the Democrats lost voters as a result.

A special feature of the election was the competition from a third party, the Free Soil Party , which because of its motto “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor and Free Men!” (“Free soil, free speech, free work and free men!”) ) was known by this name. Unlike the Liberty Party from which it emerged, it did not demand a ban on slavery, only the implementation of the Wilmot Proviso. The Free Soil Party was made up of former Whigs and Democrats; their top candidate was the Democratic ex-President Van Buren with the "Conscience Whig" Charles Francis Adams, Sr. as running mate. The Whigs' campaigning, mainly carried out by Weed, Thomas Ewing and Crittenden, was entirely focused on Taylor's personality, did not present an electoral program and avoided any commitment on the slave issue. Since Taylor remained in active military service, he refrained from campaigning for the convenience of his advisors. The campaign song "Old Rough and Ready" thematized Taylor's military career. In the early stages of universal suffrage for white men, this image of Taylor as a rough leg appealed to many voters. The Northern Whigs were in favor of the Wilmot Proviso and rejected the popular sovereignity principle. The threatened loss of voice in the south was averted by the fact that Taylor himself was a planter and slave owner. In this region in particular, the Whigs sought unity, thereby winning the votes of many Democrats. In July Taylor protested against attempts by some Whigs to make him even closer to party doctrine , and spoke out against the usual patronage of office when he received letters of petition from the first hunters. When the Whig leadership reacted too kindly the following month to an attempt at poaching by Democratic dissidents from South Carolina , they forced him to write a "second Allison letter" in early September. With neither Whigs nor Democrats committed to the slave issue, local issues decided the election, which for the first time was conducted nationwide in a single day. Taylor won the Popular Vote with 47.3% and, like Cass, won 15 states in the electoral college , including the key states of New York and Pennsylvania, which secured him a majority in the Electoral College . Overall, the Free Soil Party hurt the Democrats more than the Whigs, especially in New York. Taylor performed poorly in the western states, all of which went to Cass. Taylor became America's twelfth president as the first professional soldier . In the simultaneous congressional elections , however, it was not enough for a Whig majority in either house .

Presidency

In the White House

After the election, Taylor remained in active service until January 31, 1849 to continue to receive pay as a major general. During this phase he first met Clay, who did not recognize him at first. In December 1848, the youngest daughter married Mary Elizabeth Bliss. Since Margaret Taylor avoided the public and felt too weak for state dinners and similar events of this kind, the young couple later fulfilled important functions in the White House. At receptions, Mary Elizabeth took on the role of the unofficial first lady , while Bliss Taylor served as the private secretary. The most important political task in the presidency transition was to fill the cabinet . Since with the Ministry of the Interior a new authority with cabinet rank was introduced, it was necessary to appoint seven heads of department, with Taylor making the selection mainly according to regional aspects. This process proved difficult, especially since he delayed it until a meeting with Crittenden in February 1849. When the party leadership realized that Taylor refused to participate in office patronage and the spoils system , which were essential for building an administration at the time, they called Crittenden in vain for help. Taylor later became the first President to leave these appointments entirely to the Cabinet. In addition, to his later political disadvantage, he showed no effort to win Clay and other conservative Whigs over with a conciliatory gesture. At the end of January, Taylor started the trip to the capital without his wife. On the way he met Crittenden, who refused the office of Secretary of State because he felt obliged to this office after the Kentucky gubernatorial election . Instead, he won John Middleton Clayton, who is well networked with leading Whigs Crittenden, Weed and William H. Seward, as Secretary of State . After a very exhausting journey due to the weather, which included walking and horse-drawn sleigh rides, Taylor arrived at the Willard Hotel in Washington on February 23 with a bad cold, a hand injured by a falling suitcase and significant signs of age . Polk looked annoyed at the coming handover and forbade his cabinet members to meet with Taylor until Taylor had introduced himself to him. On February 26, he finally received Taylor at the White House; it was their first personal meeting. The short meeting took place in a friendly but very formal atmosphere. On March 1, Taylor was invited to a large dinner at the White House.

When Fillmore and Seward wanted to discuss the selection of the cabinet with Taylor on February 27, Taylor had already drawn up the personnel sheet on the basis of Crittenden's advice. This process took up the most time of all of Taylor's political preparations for the presidency. As in the case of Crittenden, he often had to fall back on the second-best solution because the preferred candidate turned down. Secretary of State Clayton turned out to be an unsuitable head of department due to his overly good-naturedness and was too indolent to fulfill the function of head of cabinet . William M. Meredith , who headed the Treasury Department after Taylor's preferred candidate Horace Binney was turned down, turned out to be a good choice. He became one of the strongest cabinet members. In the case of the Secretary of the Navy , William B. Preston was only the third choice after Abbott Lawrence and Thomas Butler King. Preston was an excellent administrative manager who, however, was hardly interested in the Navy, but mainly tried to mediate in the north-south conflict. After Toombs resigned as Secretary of War, the post went to George Walker Crawford . This could only set little accents in the government and made a name for itself mainly through the galphin affair. With Reverdy Johnson someone was Attorney General , who had actively sought this position. Johnson was a distant relative of Taylor's wife and was considered the hardest-working minister in the cabinet. He successfully led the portfolio and exerted great influence over the President and the other ministers. Ewing, who was only to be post office secretary, received the Home Office after Truman Smith and John Davis turned down the post. He was a very experienced party soldier and installed the spoils system in his department. Jacob Collamer became Minister of Post . Since he refused office patronage, but led the ministry, which rewarded well- deserved party members with the appointment of postmaster , this personality turned out to be strange. As a result, Collamer was often passed over in the cabinet when assigning posts. With Preston, he is considered the weakest minister in the Taylor administration. Overall, the result was a respectable but lackluster cabinet that lacked national recognition and, more importantly, no influence on Congress, which turned out to be the most serious weakness. In the following months office patronage was the main occupation of the cabinet; here Lincoln got nothing and Nathaniel Hawthorne lost his sinecure in customs. Taylor's most important advisor was initially Fillmore, who was increasingly replaced by Seward in this role and as head of office patronage for New York.

Instead of the usual on March 4th, the presidential inauguration took place one day later, otherwise it would have been a Sunday. On the way there, Taylor told Polk, to his horror, about such a high level of supposed ignorance and ignorance of foreign policy that he considered California and the Oregon Territory to be too far away to join the Union and they should become sovereign states . It was likely a misunderstanding as there is no evidence to support such a belief by Taylor. He delivered the inaugural address in front of the eastern portico of the Capitol in front of 10,000 spectators. Above all, the address expressed Taylor's conviction that the president has a clearly limited leadership role. Unlike Polk, he gave Congress priority over the White House in domestic affairs such as budgetary policy . Compared to other inaugural speeches of the period, the respect he paid to George Washington stood out . Overall, the speech was non-binding and did not offer any possible solutions to the pressing problems posed by the slave question and the new federal territories. Then the Chief Federal Judge Roger B. Taney took the oath of office from him.

In the first few weeks at the White House, Taylor was mainly occupied with guardsmen who followed him to his study there. Before he left for the capital, he had agreed to Albert T. Burnley's proposal to publish a pro-government newspaper in Washington. In June 1849, the first edition of The Republic appeared , which largely acted as the mouthpiece of the White House. When Burnley deviated from this line, Taylor forced his replacement by Allen A. Hall in May 1850. During his tenure there were several important funerals that required his presence as President. Polk died just a few months after he left and Dolley Madison , the widow of the fourth president, died shortly afterwards . In his funeral speech, Taylor coined the term "first lady" for the wives of presidents. In addition to the Taylors and their youngest daughter and husband, niece Rebecca Taylor lived most of the time in the White House. Because both Zachary and Margaret came from large and ramified families, relatives and friends of the Taylors were always present as guests in the house. Margaret Taylor, who resided secluded on the first floor of the White House, found her calling in the role of private hostess. Taylor, however, took part in Washington social life. Because he was in the habit of taking long walks on a regular basis, which at that time was still possible without security guards, his appearance soon became part of the usual street scene in the city. Since the White House was near the marshes of the Potomac River at that time, the climate in summer was not only uncomfortable, but also caused disease. When a cholera epidemic raged in New York and New Orleans from December 1848 and spread to the Midwest , Taylor proclaimed August 3 to be a national day of prayer and fasting in July 1849, although unlike Margaret it was not a religious day Was human and did not belong to any church.