James Monroe

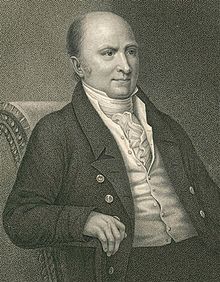

James Monroe (born April 28, 1758 in Monroe Hall in Westmoreland County , Colony of Virginia , † July 4, 1831 in New York ) was an American politician and from 1817 to 1825 the fifth President of the United States .

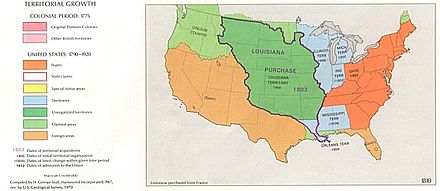

During the American Revolutionary War , he served after dropping out of his studies at the College of William & Mary as an officer in the Continental Army . Then began his political career, which led him through the Virginia House of Representatives to the Confederation Congress . At this time he received his license to practice law and made friends with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison , with whom he later determined the politics of the Democratic Republican Party as the Virginia Dynasty . After participating in the Ratification Assembly of Virginia and several mandates in the United States Senate , he was appointed Ambassador to France by George Washington in 1794 . Although he was a staunch supporter of the French Revolution , after the Jay Treaty he failed to allay the First Republic's fears of a British-American rapprochement. After his recall, which led to a break with President Washington, he became governor of Virginia from 1799 . In 1803, President Jefferson sent Monroe on a multi-year diplomatic mission to Europe where he was able to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase , while his stints in London and Madrid were disappointing. He ran unsuccessfully in the 1808 presidential election against Madison. After some time in political sideline, he was appointed foreign minister in the Madison cabinet in the spring of 1811 , and during the British-American War he also took over the post of war minister at times .

In 1816 , Monroe was the last of the generation of the founding fathers to be elected American president. One focus of his presidency was the clarification of border disputes with Great Britain, Spain and the Russian Empire in close coordination with Foreign Minister John Quincy Adams . Despite Andrew Jackson's invasion of the Spanish colony of Florida , the Adams-Onís Treaty came about in 1819 , in which Madrid ceded western and eastern Florida to America. Another central concern of Monroe was to strengthen the armed forces and coastal fortifications , which he succeeded in particular for the United States Navy . The dominant theme of his term in office were the South American Wars of Independence , and like his entire cabinet he sympathized with the anti-colonial freedom movement. After ratification of the Adams-Onís Treaty, Monroe gave up benevolent neutrality towards the young republics in Latin America and recognized it diplomatically . On December 2, 1823, he publicly declared with the Monroe Doctrine that further colonial efforts by European powers in the western hemisphere would be viewed as an unfriendly act. Though never codified , the Monroe Doctrine became the most powerful foreign policy statement by a president in American history . Domestically, Monroe drove west expansion and supported the Missouri Compromise , which could not bridge the split in the United States on the slave question , but held the American Union together until the Civil War .

As Elder statesman he was sitting at the end of the presidency of the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia and led end of 1829 the chair of the Virginia Convention . In retirement, Monroe suffered significant financial worries, not least because he was not reimbursed for his expenses as ambassador by Congress until shortly before his death. He had previously had to sell his remaining property due to financial difficulties. He died impoverished and in the care of his younger daughter on Independence Day, 1831, in New York City.

Life

Family and education

James Monroe was born in Monroe Hall in Virginia Colony to the carpenter Spence Monroe (1727–1774) and his wife Elizabeth Jones (1730–1772). He had a sister and was the oldest of four brothers. Monroe's father was a patriot and involved in protests against the Stamp Act . Since his land of 200 hectares could hardly hold its own against the competition of the large, slave- managed plantations , he worked as a craftsman and builder, which made him one of the lower end of the gentry . Spence Monroe's great-grandfather came from Scotland and fled to the Anglican colony of Virginia as a royalist after the defeat of Charles I in the English Civil War . The mother was the daughter of a Welsh immigrant whose family was one of the wealthiest in King George County . She and her brother, Joseph Jones , inherited considerable estates. Jones was a judge and one of the most influential MPs in the House of Burgesses and later a delegate to the Continental Congress . Jones was friends with George Washington and a close acquaintance of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

As was common in the Thirteen Colonies at the time, Monroe's parents taught him to read and write. At the age of eleven, his father sent him to the county's only school , Campbelltown Academy. This was considered the best in the Virginia colony, which is why Monroe was later able to take advanced courses in Latin and Mathematics at the College of William & Mary . Like his classmates, he only attended the Academy twelve weeks a year to help out on his father's farm the rest of the time. At school he made friends with future Secretary of State and Chief Justice John Marshall . In 1772 Monroe's mother died after giving birth to their youngest child, and soon afterwards his father, so that as the eldest son he assumed responsibility as head of the family and left school. Monroe's wealthy Uncle Jones now looked after her and paid his brother-in-law's debts. He took over the patronage of Monroe, shaped his political education and enrolled him at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg , where he began his studies in June 1774.

Almost all of Monroe's fellow students came from wealthy tobacco growing families who made up the ruling class of the Virginia colony and who had the most to lose in the event of UK taxation . At this stage of the American Revolution , the motherland took tough measures against the Thirteen Colonies in response to the Boston Tea Party . In Williamsburg , the British Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore , dissolved the Assembly after protests by MPs , whereupon they decided to send a delegation to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia . When the governor wanted to take advantage of the absence of the Burgesses, who had evaded to Richmond , and had soldiers from the Royal Navy confiscate the weapons stocks of the Virginia militia , alarmed militiamen and students from the College of William & Mary, including Monroe, gathered. They marched to the Governor's Palace under arms and demanded that Dunmore return the confiscated gunpowder. When more militiamen arrived in Williamsburg under the leadership of Patrick Henry , Dunmore agreed to pay compensation for the confiscated goods. Monroe and his fellow students were so angry about the governor's actions that they then conducted daily military drills on campus . Soon after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord , which marked the start of the American Revolutionary War , Dunmore fled the city on a Royal Navy frigate in June 1775 . On June 24th, Monroe and 24 militiamen stormed the Governor's Palace and stolen several hundred muskets and swords.

In the American War of Independence

On January 1, 1776, British marines led by Dunmore stormed Norfolk and burned the town. When Monroe found out about this, he volunteered for the Virginia infantry along with Marshall and fellow student and close friend John F. Mercer , despite the mourning for his recently deceased brother Spence . Because of his level of education, Monroe was hired as an officer. The entry took place as a Second Lieutenant in the 3rd Virginia Regiment, which was commanded shortly thereafter by Colonel George Weedon . After basic military training in Williamsburg, the regiment marched north on August 16, 1776, just under six weeks after the American Declaration of Independence , to join the Continental Army under George Washington in Manhattan on September 12 . It was here that Monroe gained his first battlefield experience at the Battle of Harlem Heights . Almost six weeks later, Monroe's regiment was able to repel an enemy raid during the night two days before the Battle of White Plains and inflict a loss of 56 men on the enemy without complaining about a dead man. The Monroes Regiment played a central role in the withdrawal of the Continental Army across the Delaware River on December 7th, in response to the loss of Fort Washington . On December 26th, he was among the first to cross the Delaware under the command of Captain William Washington and to open the Battle of Trenton . In Trenton, Monroe suffered a serious wound to his shoulder that damaged the artery and survived only thanks to proper first aid from doctor John Riker, who had only joined Monroe's company a few hours earlier . That same day, Monroe was promoted to captain by George Washington for his bravery .

After two months of recovery, Monroe returned to Virginia to recruit troops for the Continental Army under his command. Without success in this regard, he rejoined the Continental Army in August 1777 and was assigned to General William Alexander, Lord Stirling , as an assistant officer. At the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, he took care of the wounded Marie-Joseph Motier, Marquis de La Fayette , with whom he became a close friend. The following month he took part in the Battle of Germantown . By November 20, 1777 he was promoted to major and served as Lord Stirling's aide-de-camp . During the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, he was appointed Lord Stirling's adjutant general and helped repel a British attack on his division . Monroe continued to serve through the fall, returning to Virginia in the spring of 1779, likely for financial reasons. There he was given the rank of Lieutenant Colonel by the Virginia General Assembly without providing him with sufficient budgetary means to raise his own regiment. Instead, he was as an auxiliary officer to the governor of Virginia , Thomas Jefferson allocated and started on the advice of Jefferson toward the College of William & Mary to study law . Jefferson, with whom Monroe soon formed a close and lifelong friendship, advised his protégé to pursue a political career and made his library available to him, whereby the works of Epictet in particular had a great influence on Monroe. In June 1780 Jefferson, who had been his lifelong mentor since then, appointed him a military commissioner with the task of liaising with the Southern Continental Army, commanded by General Johann von Kalb in South Carolina . At the end of 1780 the British moved into Virginia and Monroe, who had been a Colonel in the meantime , was given command of a regiment for the first time without being able to make a decisive contribution to the defense. Further management assignments were denied to him despite extensive efforts. After the Battle of Yorktown , Monroe retired from active service in November 1781.

Early political stations

In 1782, Monroe was elected to the Virginia House of Representatives for King George County . Shortly thereafter, at an unusually young age, he successfully ran for the eight-member Governor's Council . In June 1783, the election to the fourth Confederation Congress followed . He was able to defend this seat in the next two elections. At the Confederation Congress, he made a name for himself at the forefront of those delegates who took a national perspective and saw themselves not just as citizens of their respective states . Monroe developed a keen interest in American foreign policy and, from a military perspective, recognized the fundamental problem of the United States that later determined his presidency: the conflicts that arose when the natural expansion of the young nation collided with the territorial claims of European powers in North America .

He supported Washington and the Society of the Cincinnati in their endeavor to compensate less fortunate veterans of the War of Independence with Frontier . In this context he toured the Ohio Country and later Kentucky in 1784 and 1785 . The question of the shifting of the border to the west , which he saw as existential for the future of the United States, preoccupied Monroe throughout his political career. He worked to clarify the legal status of the areas that America had been given for use in the Peace of Paris . Another goal of Monroe in the Confederation Congress was the free navigation on the Mississippi . His interest in the economic development of the American West, in which Jefferson encouraged him, was also of a personal nature, since, like other founding fathers, he was involved in land speculation and had received 2,000 hectares of land rights in Kentucky for his service in the Continental Army. Unlike Madison and Washington, who wanted to incorporate these territories into existing states, Monroe and Jefferson advocated admission as new states to the United States. Perhaps more than any other political leader of his generation, he recognized that the national drive for western expansion , which was first carried by the settlers and later by European immigrants , could no longer be contained.

On this issue, he came into conflict with Secretary of State John Jay . This came from New York City and represented the interests of New England , which was interested in good trade relations with the kingdoms of France and Great Britain, which were potentially endangered by the territorial claims of Virginia and North Carolina west of the Mississippi and in the later Northwest Territory . In addition, Jay saw in the expansion to the west and the development of the local waterways , especially the port of New Orleans , a serious economic competition for the West India trade in New England. In 1787, Monroe enforced the Northwest Ordinance in the Confederation Congress , which was the legal basis for the creation of the Northwest Territory. From that time until the 1810s, Monroe was perceived by the public as the only politician of national importance who stood up for the interests of the western border areas. During his time in the Confederation Congress, through Jefferson's mediation, the friendship with James Madison began .

In this phase of his life, Monroe's private life was determined by two recurring themes: health restrictions that regularly tied him to bed, and financial difficulties. After serving in the Continental Army, he had switched directly to politics and was still not admitted to the bar , which meant that an important source of income was missing. On February 16, 1786 he married Elizabeth Kortright , who came from the high society of New York City. They met when the Confederation Congress was meeting in Federal Hall in Manhattan . Monroe's father-in-law was a once wealthy West Indian planter impoverished by the American Revolution. The bond between Monroe and his wife was very close and they were perceived as a complementary couple. Later as First Lady , she made an enchanting impression on the guests due to her grace and natural beauty, but due to poor health, she significantly restricted the societies in the White House compared to her predecessor Dolley Madison . The marriage resulted in three children, of whom the daughters Eliza (1787–1835) and Maria (1803–1850) reached adulthood.

In the fall of 1786 the Monroes moved to his uncle Jones' house in Fredericksburg , where he successfully passed the bar exam. Faithful to politics, Monroe was soon elected to Fredericksburg City Council and soon after to the Virginia House of Representatives . In June 1788 he was a participant in the Virginia Ratification Assembly, which voted on the adoption of the United States Constitution. Monroe took a neutral position between the supporters of Madison and opponents of the Constitution . He called for the constitution to include guarantees regarding free navigation on the Mississippi and for the federal government to have direct control over the militia in the event of a defense. He wanted to prevent the creation of a standing army , which turned out to be a critical point of contention between the federalists and the anti-federalists , who, as the nucleus of the Democratic-Republican Party, rejected an overly strong central government. Monroe also opposed the electoral college , which he saw as too corruptible and vulnerable to state interests, and advocated direct election of the president. In the end, Monroe voted with the anti-federalists against ratifying the American Constitution, possibly due to concerns that the future federal government would sacrifice the interests of the West to those of the East Coast states. A concession to the anti-federalists, who were defeated in the vote on June 27, 1788 by 79-89 votes, was to recommend to Congress the inclusion of 20 constitutional amendments, two of which went back to Monroe. In the subsequent election to the 1st Congress of the United States , the anti-federalist persuaded Henry Monroe to run against Madison. Madison eventually won the House of Representatives seat , which didn't detract from their friendship.

After this defeat, Monroe and his family moved from Fredericksburg to Albemarle County , first to Charlottesville and later to the immediate vicinity of Monticello , where he bought an estate and named it Highland . Some historians see this change of residence to the wooded interior of Virginia as a symbolic break with the planting elite of the East, who cultivated a European lifestyle, and a turn to the settlers at the foot of the Allegheny Mountains .

In December 1790, Monroe was elected to the American Senate for Virginia , which was then meeting in the Congress Hall of the then capital, Philadelphia . Since the Senate, unlike the House of Representatives, met behind closed doors, the public paid little attention to it and focused on the House of Commons . Monroes therefore requested in February 1791 that the meetings of the Senate be held publicly, but this was initially rejected and only implemented from February 1794. In the federal government, which was largely under the influence of the federalists around Finance Minister Alexander Hamilton , two factions soon emerged: the anti-administration party or republicans and the pro-administration party or federalists. The conflict mainly revolved around the question of whether the rights of the individual federal states or the nation were paramount, but also expressed itself in foreign policy in the dispute about the extent to which revolutionary France should be supported in the First Coalition War . This dispute dominated the political scene for the next two decades and first came to light during the discussion about the establishment of the First Bank of the United States . In the vote, Monroe was one of five senators who voted against the introduction of this central bank. The Anti-Administration Party began to form around Jefferson in the Democratic Republican Party, with Madison and Monroe being his most important helpers as organizer and militant party soldier . The political atmosphere became increasingly polarized : while the federalists saw irrepressible and provincial primitives in their opponents, the Republicans around Jefferson saw the federalists as monarchists . When Monroe took part in Congressional investigations into Hamilton's illegal transactions with James Reynolds in 1792 , this led to the uncovering of the first political sex scandal in the United States: the payments had been hush money and Hamilton's affair with Reynolds wife was secret to keep. Hamilton Monroe never forgave this public humiliation, which had almost led to a duel between the two. In 1793/94, Madison and Monroe responded to pamphlets accusing Jefferson of undermining Washington's authority with a series of six essays. Most of these sharply worded replicas came from the pen of Monroe.

The split between federalists and anti-federalists was not only caused by different particular interests , but also by diverging philosophies of life, regional cultures and historical experiences. The Republicans under Virginia's leadership were shaped by the self-sufficient plantation system that depended on land ownership and was skeptical of cities, concentrated finance and central government. The planters of the southern states were spiritually influenced by the authors of Ancient Greece and the Roman Republic . The federalists, on the other hand, were mostly urban shopkeepers, traders and artisans who were dependent on sea trade and did banking. As the Republican leader in the Senate, Monroe soon became involved in foreign affairs. In 1794 he appeared against Hamilton's appointment as ambassador to the United Kingdom and friend of the French First Republic . Since 1791 he had sided with the French Revolution in several essays under the pseudonym Aratus .

Ambassador to France

In April 1794, Monroe self-confidently asked Washington in a letter for a personal audience to dissuade him from appointing Hamilton as ambassador to London . Washington, who had already dropped this plan, did not appreciate him in reply. Nevertheless, he appointed Monroe to succeed Governor Morris as ambassador to France in the middle of 1794 after Madison and Robert R. Livingston had rejected the offer. Monroe took up this post at a difficult time: France, Great Britain and Spain were the most important trading partners of the United States in the First Coalition War and all had territorial interests in North America : The Kingdom of Great Britain was the northern neighbor with Upper and Lower Canada , the First French Republic registered in the west ownership claims to the huge colony Louisiana , which it had lost to Spain in the Peace of Paris in 1763 , which had also been in the possession of East and West Florida since the Peace of Paris in 1783 . Louisiana and Floridas in particular hampered further expansion of the United States. America's negotiating position was made considerably more difficult by a lack of military strength. In addition, the conflict between Paris and London in America intensified the confrontation between the Anglophile Federalists and the Francophile Republicans. While the federalists only aimed at independence from Great Britain, the Republicans wanted a revolutionary new form of government, which is why they strongly sympathized with the French First Republic.

Washington and Foreign Minister Edmund Randolph , who both had a more neutral stance on revolutionary France and soon distanced himself from Paris, informed Monroe of the diplomatic mission of his former adversary and staunch federalist Jay, which was taking place in London at the same time : while they assured him, Jays The contract in Great Britain only dealt with compensation issues arising from the American War of Independence, and this actually had a much more far-reaching negotiating mandate. In addition to the general requirement to continue to secure close relations with France, Monroe was to clarify two specific questions with Paris: on the one hand, the claims to compensation for American merchant ships whose British goods had been confiscated by revolutionary France, and on the other hand, free navigation on the Mississippi . Monroe's passionate and amicable greeting at the induction ceremony before the National Convention was later criticized by Jay and Randolph for their assertiveness. Washington saw the speech as "not well developed" in terms of location and given America's neutrality in the First Coalition War.

So instructed by Randolph, Monroe assumed that he should achieve a deepening of US-French relations, even though Washington only wanted to maintain the status quo. He was visibly torn between his role as representative of the American government and that of the militant party politician of the Francophile Republicans. Monroe was able to establish good and useful relationships in France, in particular with Merlin de Thionville , Jean Lambert Tallien , Antoine Claire Thibaudeau and Jean François Reubell . On November 21, 1794, he received a promise from the welfare committee that Paris would again adhere to the provisions of the American-French alliance treaty of February 1778 and that American ships would be granted free access to its ports. However, the federalists in the domestic government did not attach great importance to this agreement and continued to focus on relations with London.

When the Jay Treaty with the Kingdom of Great Britain, signed in November 1794 , became known, Monroe in Paris got caught up in a web of international intrigues and rumors that revolved around the secret contractual agreements. In response to Monroe's inquiries, Jay first assured him that the agreement with London would in no way contravene the existing treaty with France, whereupon Monroe hastily promised the French that he would inform them of the precise provisions of the Jay treaty. Shortly afterwards, Monroe received the text of the treaty with the exact opposite instruction not to pass the content on to France under any circumstances. Although a Paris newspaper published the wording of the Jay Treaty in August 1795, Monroe continued to have orders to assure France that this agreement would not alter their friendship.

In February 1795, Monroe obtained the release of all American citizens imprisoned since the French Revolution and the wife of his friend Marquis de La Fayette. Already in July 1794 he had arranged for the release of Thomas Paine and taken him in. When, despite Monroe's objections, he was working on a diatribe against Washington, they parted ways again in the spring of 1796. Monroe convinced the French to include navigation rights on the Mississippi in their peace negotiations with Spain, which ultimately resulted in the Peace of Basel . Since Monroe had acted as an unofficial mediator to France for Spain, Madrid was ready to make this concession, which was finally fixed in the Treaty of San Lorenzo on October 27, 1795, and America, in addition to free navigation on the Mississippi, restricted rights of use for the port of New Orleans conceded.

Immediately after Timothy Pickering succeeded Secretary of State Randolph, who had been the only Francophile member in the Washington cabinet, in December 1795 , he worked on the dismissal of Monroe. When Monroe reported his answers to the Board of Directors on March 25, 1796 , which complained about the Jay Treaty, he sent it as a summary and not fully documented, as Paris asked for a new draft of this correspondence. Pickering saw it as a sign of Monroe's unsuitability and, together with Hamilton, convinced Washington to replace Monroe as ambassador. The letter of resignation from Pickering, written on July 29, 1796 and deliberately delayed, did not reach Monroe until November 1796 to prevent his return before the presidential election . Until his departure, Monroe had to see how the progress he had made was reversed and France, in response to the passage of the Jay Treaty in Congress, resumed the seizures of American ships and ended diplomatic relations with America. Monroe's biographer Gary Hart ultimately sees this failure as being due to his transferring the polarized domestic conflict situation in America to the much more complex European tension network. During this phase, Monroe's aggressive approach to foreign relations and the self-image of America's active role in world politics that went beyond mere security, which set him apart from all other founding fathers, emerged for the first time.

Governor of Virginia and Louisiana Purchase

After his return from Paris in 1797, Monroe was in New York for some time in order to obtain reparation from Pickering for his unjust deposition. At home in Virginia, he published a letter of defense stating that he and his friendship with France were sacrificed to bring them closer to London. This challenged John Adams to a violent counter-attack. With the support of Jefferson and Madison, Monroe finally wrote the 400-page work A view of the conduct of the executive in the foreign affairs of the United States, connected with the mission to the French Republic, during the years 1794, in 1797 , 5, & 6 , which sharply attacked the Washington government and accused it of acting against the interests of America. For Washington this meant the final break with his former officer and prompted him to publish a damning criticism of Monroe. Monroe was already heavily in debt at this stage, as the remuneration as an ambassador had been far below the necessary expenses and his private income was far too low to cover these costs.

In 1799, Monroe was elected governor of Virginia . At this time, the decline of the federalists began, who became increasingly entangled in camp battles between Hamilton and Adams, especially over the question of the quasi-war with France. Since Jefferson on the Republican side failed as Vice President as opposition leader and Madison did not want to take advantage of the misery of the federalists, Monroe filled this gap. He developed initiatives that went beyond the limited powers of a governor without being able to achieve much. Like his mentor Jefferson, he attached particular importance to the public education system. Monroe also campaigned for state support for training and equipping the militias. After Gabriel Prosser's plans for a slave revolt were uncovered at the end of August 1800 , Monroe called in the militia, had weapons and gunpowder removed from all stores and the prison in which the conspirators were imprisoned was secured with palisades . When the general fear, which was fed by the slave rebellions of the Haitian Revolution at that time, proved to be unfounded and there were no reprisals after the execution of the conspirators, he dissolved the militia except for a few men by October 18. After three years in office, Monroe retired. Not much later, Jefferson, now American President, asked him to go on another diplomatic mission to France. There he was supposed to support Ambassador Livingston and negotiate with Paris about the rights of use at the port of New Orleans, the free navigation on the Mississippi and the two Floridas. Jefferson saw the first two points as endangered, since the colony of Louisiana was ceded by Spain in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso 1800 to the First French Republic. On January 11, 1803, the President finally appointed Monroe an envoy with special negotiating authority and ambassador to London.

Arrived in Paris, Monroe got involved in the negotiations on the Louisiana Purchase , which Ambassador Livingston had led for America until then. Although the latter had only negotiated a cession of New Orleans to America, Napoleon Bonaparte offered, through his Foreign Minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, the acquisition of the entire colony of Louisiana, while he declared West and East Florida to remain part of Spain. This contradicted the specifications of Jefferson, who had given the acquisition of the two Floridas and New Orleans as a goal. Nevertheless, the deal was closed and the contract for the Louisiana Purchase signed on April 30, 1803. At dinner the following day, Monroe was introduced to Napoleon. In their conversation, Napoleon predicted a coming war between America and Great Britain, and he was proved right. Shortly thereafter, Monroe was sent on to London to negotiate the forced recruitment of American seamen for the Royal Navy and a possible defense alliance to protect their own maritime trade. Monroe stayed in London from July 1803 to late autumn 1804. Without having made significant progress in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland , Monroe was further summoned to Spain to negotiate over the Floridas. When he arrived in Madrid on January 2, 1803, he found the atmosphere of conversation poisoned, for which the American ambassador to Spain , Charles Pinckney , had provided with crude threats of violence. In negotiating the open territorial issues affecting New Orleans, West Florida and the Rio Grande , Monroe got stuck and was treated condescendingly. Frustrated, he left Spain after six months and returned to London, where he spent the next year and a half negotiating trade and economic agreements and, above all, the British practice of Shanghai American seafarers. In English ports he could see with his own eyes American prize ships come in .

Politically sidelined

In early 1806, John Randolph of Roanoke asked him to run in two years against Secretary of State Madison, who was built by Jefferson as his successor. Monroe refused this request for the time being. In the meantime, in collaboration with the envoy William Pinkney, he reached an understanding with London that clarified a number of outstanding financial and economic questions. Jefferson rejected this agreement, however, as it left out the forced recruitment. The president was also keen to maintain the anti-British sentiment in America from which Madison benefited, although he denied that motive to Monroe. Monroe took the rejection of his negotiation result as an offense and felt deeply shaken in his friendship with Jefferson and Madison, which is why his personal relationship with the two cooled for some time. After his return to America in December 1807, the still angry Monroe decided to run against Madison in the presidential election in 1808 , which he wanted to demonstrate the strength of his political position in Virginia. Monroe was the candidate of the so-called "Old Republicans" (German: "Old Republicans") around Randolph of Roanoke and John Taylor of Caroline , who viewed Jefferson and Madison as traitors to the republican ideals, as they expanded the powers of the federal government over the individual states had.

After a clear defeat to Madison, in which he could not win a single vote in Electoral College , Monroe, who had fallen out of favor with the majority of Republicans because of the candidacy, withdrew into private life for the next few years. This marked the bottom of a difficult period that has been marked by losses and disappointments since the Louisiana Purchase. The plan to sell his second house in Loudon County , Oak Hill , in order to use the proceeds to renovate and expand Highland failed because of the low real estate prices. Like his neighbor Jefferson, he experimented with new horticultural techniques in order to switch from tobacco, whose value was declining, to wheat. In September 1808, his daughter Eliza married the judge George Hay , who later became one of the chief political advisers to President Monroe. In 1810 he rehabilitated himself in the party and was elected to the Virginia House of Representatives in April of that year. On January 16, 1811, he was again governor of Virginia, which remained only a brief episode, since almost two months later Albert Gallatin asked him on behalf of Madison if he was ready to take over the office of foreign minister as Robert Smith's successor .

Minister in the Madison Cabinet and British-American War

When he was promised that he would be used in Madison's cabinet as an independent minister and not just as a mouthpiece for the president, Monroe consented and became foreign minister in March 1811. The cordial relationship between Monroe and Madison had become a complex and professional one. For both the President and the Foreign Secretary, who worked closely together and hardly had any differences, the conflict with Great Britain was the dominant theme in the next few years and, to a lesser extent, that with France. London's refusal to listen to American complaints, particularly about the forced recruitment, drove both states ever closer to war. Monroe and Madison agreed that the reputation and interests of the United States did not permit such discrimination. According to Ammon, Monroe's entry into the cabinet meant that a solution to the ongoing controversy between America and Britain became inevitable, whether through a peaceful settlement or an armed conflict. Although as ambassador to London a few years earlier he had negotiated an agreement that Jefferson had rejected, he brought a more bellicose mood to the Cabinet. At the State of the Union Address in November 1811, Madison called for an auxiliary force to be set up and the United States Navy to be enlarged. Monroe was given the task of getting these plans through Congress. With Henry Clay and Madison, Monroe planned a new embargo against Great Britain, which was passed in Congress in March 1812 and served as a test run to determine whether there was a political majority for war. On June 1, 1812, Madison finally declared war , and two weeks later the Senate approved it with a narrow majority.

After the outbreak of the British-American War , Monroe sought a military command, especially since he only attached secondary importance to the State Department and diplomacy. After the successful siege of Detroit by the British Army in August 1812, he wanted to lead the reconquest of Detroit and proposed Jefferson as his successor in the State Department , which the President immediately rejected. Instead, Madison made him acting Minister of War in January 1813 as the successor to the unsuccessful William Eustis . Monroe turned the Deputy Head of State Department over to Richard Rush . In a very short time, Monroe prepared a detailed report on the military personnel required for the coastal defense and the planned summer offensive. It planned to recruit an additional 20,000 regular soldiers on a one-year basis. The Senate prevented Monroe's appointment as official minister in this department in order not to further increase the dominance of Virginia politicians in key positions. According to Madison's biographer Gary Wills , on the advice of his son-in-law Hay, Monroe had only intended a short-term position as Secretary of War from the outset, as he feared for his own presidency in this position in the face of a long and unpopular war looming. Instead, in February 1813, a bitter rival, John Armstrong Jr., became Monroe's official war minister. Monroe suspiciously spied on Armstrong's ministerial correspondence when he saw a military front line command outside the capital. When British warships first appeared in the mouth of the Potomac River in the summer of the same year and Monroe insisted that Washington, DC take defensive measures and that a military intelligence service be set up in the form of a pony express to Chesapeake Bay , the Secretary of War rejected this as unnecessary. Since there was no functioning reconnaissance , Monroe put together a small cavalry unit on his own and scouted the bay himself from then on until the British withdrew from it.

After Napoleon's defeat in the Sixth Coalition War in the summer of 1814, the British focused on the American theater of war and prepared to invade the capital. Rumors of this warning Armstrong once again ignored him. When, on August 16, 1814, another British fleet with 50 warships and 5,000 soldiers massed itself in the mouth of the Potomac, Madison had seen enough and organized the defense of Washington with Monroe. Monroe personally scouted Chesapeake Bay with a squad and on August 21 sent the president a warning of the impending invasion so that Madison and his wife could escape in time and the state assets and residents could be evacuated. Three days later, Monroe met the President and Cabinet at the Washington Navy Yard in a desperate attempt to defend the capital. Then he rode on to Bladensburg to support General Tobias Stansbury , without being able to prevent the defeat in the Battle of Bladensburg . The British then invaded the District of Columbia, looted the city and burned down the public buildings. Shortly thereafter, Madison accepted Armstrong's resignation and this time appointed Monroe not only acting but also permanent secretary of war. Since General William H. Winder was in Baltimore , Monroe was Secretary of War and Executive General for Washington at that time.

As Secretary of War, Monroe broke the Republican doctrine of leaving national defense to the state militias and planned to convene a conscript army of 100,000 to fend off the British invasion that was threatening from Canada . For this purpose, all men between 18 and 45 years of age should be divided into groups of hundreds and have the responsibility to provide four serviceable soldiers each. Because the war was about to end, this was never implemented. In September 1814, Monroe focused on assisting General Samuel Smith in the defense of Baltimore. After winning the Battle of Baltimore , the British were eventually thrown out of Chesapeake Bay. War spending made it necessary for the president to break another Orthodox Republican tenet and found a new central bank after the First Bank of the United States charter expired in 1811. Monroe, who was one of the first party leaders to recognize that the Republicans had changed since 1800 and that their supporters were now more urban and bank-friendly, especially in New England and the Central Atlantic States , did not oppose this. In addition, he had continued to borrow in order to cover the costs of the war out of his own pocket. After the favorable peace of Ghent and Andrew Jackson's victory in the Battle of New Orleans , Monroe resigned as Secretary of War on March 15, 1815 and took over the management of the State Department again. Monroe, who as Minister of War claimed the victories of New Orleans and the Battle of Plattsburgh , emerged politically stronger and as a promising presidential candidate from the British-American war. Before he left the War Department, he prepared a report for the Senate Committee on Military Affairs that recommended a regular army of 20,000 men for peacetime and reinforcement of the coastal fortifications , doubling the number of staff before the war of 1812. The next six months he spared his health, which had been affected by the enormous workload in the previous years.

Presidential election 1816

In October 1815 he returned to the capital and was traded as Madison's successor, since the State Department was a stepping stone to the presidency. While Monroe never enjoyed Jefferson's great popularity, he was widely respected. Like Jefferson himself at the time, President Madison was externally neutral as Monroe prepared to run for the 1816 election . Even so, it was widely believed that Madison supported Monroe as his successor. With the decline of the federalists, who were perceived as disloyal because of their pro-British stance and rejection of the war of 1812, there was no longer any serious opposition party, the republican caucus in Congress was decisive for Monroe's victory . In this he was able to beat the party’s internal competitor, Treasury Secretary William Harris Crawford , with 65-54 votes. To Monroe's running mate was Daniel D. Tompkins selected. In the presidential election in November 1816, he won clearly against the federalist Rufus King and achieved a majority of 183-34 votes in the Electoral College. Monroe's inauguration as the last president of the generation of the Founding Fathers took place on March 4, 1817.

Presidency

In his inaugural address, Monroe praised the courage of his compatriots in the British-American War and America as a vibrant and prosperous nation. National security occupied most of his speech . Monroe called for more attention to be paid to the military and the coastal fortifications to be strengthened. He warned against considering the geopolitical island position of the United States as a sufficient protective factor, especially since the nation depends on safe sea routes and fishing. In future wars that cannot be ruled out, the adversary could destroy the American Union if it were not strong enough, and thus lose its character and its freedom. Furthermore, foreign policy goals are easier to achieve from a position of strength than from a position of weakness. Since Monroe was the first president to take office in a phase of peace and economic stability, the term “ Era of Good Feelings ” soon came up . This period was marked by the undisputed dominance of the Republicans, who by the end of Madison's term in office had adopted some of the federalists' issues, such as the creation of a central bank and protective tariffs . The party political situation was considerably less heated and polarized than it was during the presidential elections in 1800 , but especially at the end of Monroe's term in office, the Republicans were below the level of official politics due to strong fragmentation, fiercely rival factions in states like New York and Virginia, and bitter personalities Rivalries shaped. Monroe saw it as the president's duty to stand above these conflicts, which is why he was passive about this development, even as it reached into the government team. The historian Hermann Wellenreuther sees this as a deficit of Monroe, which has contributed to the polarization of the political landscape.

Geographical considerations played an important role for Monroe in creating the cabinet . He wanted to increase the reach of Republicans and the unity of the nation by selecting people from different regions of the United States for important ministerial posts. The State Department was of particular importance here. Since all of the first five presidents except John Adams were Virginians, so that there was already talk of a Virginia dynasty , Monroe wanted to avoid any suspicion of preferring this state. It was not only for these reasons that Monroe named John Quincy Adams , the son of the second president, as his secretary of state, but also because his exceptional diplomatic talent was undisputed and he had broken with the federalists as a supporter of Jefferson's trade embargo in 1807. They had known each other since the peace negotiations with Great Britain in 1814, in which Adams had participated with great intensity. Your personal relationship became the most important for Monroe during his presidency. Only Jefferson and Madison's working relationship matched the accomplishments of their collaboration at this early stage in the United States. Adams provided the President with position papers at their daily work meetings, which the President edited or referred back to Adams for clarification. He called the cabinet together less to seek advice and more to establish consensus between the ministers and himself, since his positions were usually fixed before the meeting.

Until the completion of the restoration of the White House in September 1817, which was burned down by British troops after the Battle of Bladensburg, Monroe lived in what is now Cleveland Abbe House . This house had already been his residence as foreign and war minister. Monroe revived a tradition abandoned after Washington and toured the country during his presidency, for example in May 1818 when he toured the forts in Chesapeake Bay and around Norfolk . In contrast to the first president, this was not intended as a symbolic gesture of unity, but served to attract local support for the national defense budget. Specifically, his aim was to set up a line of forts on the coast as a line of defense, better secure the northern border and build depots and shipyards for the navy, as he repeated in his first speech on the State of the Union on December 2, 1817. This became a focus of his presidency, which he affirmed in the speech on the occasion of the second inauguration in March 1821. In March 1819 Monroe made another visiting trip that took him via Norfolk to Nashville , where he had a week-long meeting with Jackson. He also visited the fortifications and the construction sites of the forts Monroe and Calhoun .

In his last State of the Union address in 1824, Monroe announced a reduction in national debt and appealed one last time to ensure national defense and the protection of maritime trade routes with a chain of coastal fortifications and a strong navy. In this address he did not look to Europe or South America, as he had so often before, but, like a large part of the nation as a whole, to the Wild West . He asked Congress to authorize the construction of a fort in the mouth of the Columbia River and to keep a naval squadron on the west coast. In the controversial and intense presidential election campaign of 1824 between the Republicans Jackson, Adams, Crawford and Clay, Monroe took no part and refused to name his favorite. By the time he left the White House, the political scene was fragmented to an unprecedented extent and marked by personal rivalries.

Defense policy

When Monroe took office, he was faced with a number of foreign and security policy challenges. In the Pacific Northwest, American claims to territory clashed with those of Tsarist Russia , while navigation rights on the rivers in the west remained disputed and the settlers there met resistance from the Indians of North America . In the south, on the border with the Spanish colony of Florida , there was unrest due to the uprisings of the Seminoles , which ultimately led to the First Seminole War , and piracy , against which a weak Spanish administration did nothing. Last but not least, the attitude of the United States towards the Latin American republics that emerged during the South American wars of independence had to be clarified . On the one hand, these border conflicts and the protection against interference by foreign powers on the North American continent preoccupied the Monroe government to a great extent, and on the other hand, the peace in Europe after the Congress of Vienna offered freedom to normalize relations with the European powers.

During his tenure as a Senator in Congress, Monroe had blocked attempts by the Washington government to enlarge the regular army. As governor of Virginia, he campaigned for the state's militias to be strengthened, but this was rejected for reasons of cost. Around this time his attitude towards a standing army began to change, which the classical republicans had already rejected in antiquity because it could be used as a means of tyranny in peacetime . The British-American War finally convinced Monroe that the national security of expanding America could no longer be guaranteed by the militias alone.

The navy survived the budget cuts as a result of the economic crisis of 1819 better than the United States Army . This was mainly due to the fact that it turned out to be indispensable for protecting American merchant ships against piracy. In his final year in office, Monroe put an eight-year fleet building program through Congress that comprised nine ships of the line , twelve frigates, and three floating batteries . The permanent stationing of ships of the United States Navy off the American west coast had already been established two years earlier . At Adams' urging, Monroe sent a frigate to the Antarctic Peninsula to anticipate British expeditions and territorial claims.

As for his predecessors in office, maritime trade was an important issue for Monroe. It was particularly concerned with the condemnation of the maritime slave trade , which was decided in the Peace of Ghent. Monroe and Adams stood by this agreement, but wanted non-state sovereignty rights to be surrendered to an international agency with permission to search American ships. The public opinion , which was only on the part of the president, began under pressure from abolitionists from the Northeast and the American Colonization Society to turn. This society pushed for the return of freedmen to Africa , where they founded the Liberia colony . When the congressional committees were willing to allow international inspections with limited rights, Adams blocked it. Monroe then sought, despite the opposition of his foreign minister, a bilateral agreement with Great Britain, which allowed searches on the high seas. He hoped that this agreement would clarify other open issues such as border disputes around Maine and the Oregon Country . When Congress restricted inspections to African coastal waters, London broke negotiations. After that the door was permanently closed for America and Great Britain to take action against the slave trade.

Adams-Onís Treaty

At the end of October 1817, several longer cabinet meetings took place. One of the meeting points was the declarations of independence of some former Spanish colonies in South America and the question of how to react to them. On the other hand, it was about the increasing piracy , especially from Amelia Island . Piracy on the southern Florida border was intensified by smugglers, slave traders, and privateers who had fled the Spanish colonies over which the motherland had lost control. As usual, Monroe had sent the ministers questions and information material beforehand in order to then bring about a clarification with the cabinet in a long discussion. After three meetings, the decision was made in the same month to use the United States Army against the marauders in Amelia Island and Galveston . In addition, the border areas of Georgia and Alabama with the Florida should be pacified, where the Seminoles rebelled. General Edmund P. Gaines received permission to place the Seminoles on the territory of the Spanish colony of Florida should they flee across the border there. Just in case they sought refuge in Spanish forts, Gaines should refrain from further prosecution.

In April 1818 the Cabinet decided to keep Gaines' successor Jackson, who had led the anti-piracy operations in Amelia Island, stationed in Florida until Madrid had established a functioning administration there. Jackson's military actions represented a communication problem for Monroe, as the situation reports always arrived in Washington with a long delay. During this cabinet meeting, for example, it was not yet known that Jackson had driven the Spanish governor of West Florida and his crew out of Fort Barrancas in Pensacola after eliminating the pirates, risking war with Spain. Jackson made this decision after learning that the Seminoles had been assisted by this garrison in their raids on Georgia settlements. With regard to the South American Wars of Independence, the ambassadors to Europe were instructed to declare on their own responsibility that the United States regarded any interference in the affairs of South America as a hostile act. The Cabinet did not meet again about the new situation in Florida until July 15, 1818, when Monroe returned from a trip from North Carolina.

At that meeting, under the leadership of Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, all cabinet members except the Secretary of State condemned Jackson's actions and called for an investigation. Adams endorsed Jackson's operations, saw them covered by his orders, and advocated holding on to the Pensacola and Saint Marks conquests . Monroe shortly thereafter fixed the official position of the government in a letter from Adams to the Spanish ambassador Luis de Onís , which he edited accordingly, removing all justifications for Jackson's actions. In addition, Monroe emphasized that Jackson had exceeded his order , but had come to a new assessment of the situation on the basis of previously unknown information at the site of the war. However, Jackson had already told him in a confidential letter six months earlier that East Florida was to be annexed. According to historian Sean Wilentz , Jackson's willingness to conquer Florida for the slightest cause was very likely the reason Monroe chose him on this mission. Monroe offered Spain to vacate the forts as soon as they sent appropriate garrisons. According to Ammon, Monroe's stance had already been established before the cabinet meeting, but he had held it anyway in order to position himself between the two opinion groups of his ministers. On the one hand, he was able to keep under control every movement in Congress that was aimed at rebuking Jackson, and on the other hand, he could keep Jackson's conquests as a tactical advantage, especially since he had achieved the status of a folk hero . By finding that Jackson had violated his instructions, Monroe avoided constitutional problems for his government and a declaration of war by Spain and its allies. In a letter to Jackson on July 19, he explained why he had not officially approved of the unauthorized conquests. The lack of backing from the president led to the lifelong rift between Monroe and Jackson.

Although Jackson continued to take military posts in the Spanish colony of Florida, Adams managed to negotiate calmly with de Onís over the acquisition of the two Floridas and the establishment of the western border of the Missouri Territory . This was the former Louisiana Territory , which had been renamed to avoid confusion with the newly created state of Louisiana . The Missouri Territory joined the Viceroyalty of New Spain in the west . The New Spanish province of Texas , whose annexation was vehemently demanded by American public opinion, was in dispute . After Adams advanced in the Floridas negotiations and approached the dispute on the western border of the Missouri Territory, Monroe deftly increased pressure on Madrid and announced that he would consult with Jackson on how to proceed on the matter. Ultimately, Adams was able to convince the President to be satisfied with the acquisition of the two Floridas, to forego Texas for the time being and to accept the Sabine , Red and Arkansas Rivers as the border with the Viceroyalty of New Spain . The main reason for this was that the northeastern states viewed the expansion to the south and west with skepticism, as they feared an expansion of slavery into these regions. In addition, in view of the Mexican War of Independence , Monroe foresaw a new negotiating partner for the Texas question in the near future.

On February 22, 1819, the Adams-Onís Treaty came about . He determined the acquisition of the Spanish colony Florida by the United States and opened the Missouri Territory north of the 42 ° latitude to the west to the Pacific , creating the Oregon Country . This gave Washington access to the Pacific for the first time in a legally binding form. The Adams-Onís Treaty was ratified by Congress in 1821. This brought an end to the negotiations between Spain and America, which had lasted with interruptions for over 25 years. In the Oregon Country itself, America's economic interests and territorial claims collided with those of Russian America , which had trading posts all the way down to San Francisco Bay , and those of Great Britain. The situation worsened in the autumn of 1821 when Saint Petersburg, north of the 51 ° latitude, closed the Pacific territorial sea of America within a 100-mile zone to foreign ships and thus shifted its territorial claim by four latitudes to the south. In April 1824, Monroe reached an agreement with Russia that limited the territorial claims of Russian America to territories north of the 54 ° 40 'parallel.

South American Wars of Independence

Red: Royalist reaction

Blue: Under the control of the separatists

Dark blue: Under the control of Greater Colombia

Dark blue (motherland): Spain during French invasions

Green: Spain during the Trienio Liberal

The South American Wars of Independence were the political issue that preoccupied Monroe and Adams most during their tenure. Monroe had less political control than desired in this matter and was driven a bit by Clay from 1821 onwards. This called for a Speaker of the House , the diplomatic recognition of the United Provinces of Río de la Plata and the privateering full support of the anti-colonial liberation movements. With this commitment, Clay wanted to establish himself as the successor to Monroe. Public opinion in the United States was overwhelmingly on the side of the South American revolutionaries, a position that Monroe, as a staunch Republican, shared emotionally. His initial stance was to favor the liberation movements as much as possible without risking war with Spain while negotiations with Madrid were ongoing over the Florida and the western border of the Missouri Territory. For Monroe and Adams, clarifying the border disputes had a higher priority, which resulted in the classic case of a conflict between interest politics and value orientation. After their respective declarations of independence, the South American republics quickly sent emissaries to Washington to ask for diplomatic recognition and economic and trade relations. In return, Monroe sent three representatives on a naval ship to South America to sound out the situation on the ground. In 1818, Monroe had a representative of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata communicated via Adams that his position in this conflict was "impartial neutrality", which partly reassured the faction around Clay. Although not diplomatically recognized for the time being, the young republics enjoyed almost all of the advantages of a sovereign nation in economic, commercial, and diplomatic relations with the United States. Monroe and Adams also guaranteed friendly relations with the later emissaries of other republics.

In all speeches on the State of the Union, Monroe expressed sympathy for the South American struggle for freedom, including in 1820, although Adams had advised against it. With the Adams-Onís deal signed, the pressure on Monroe to be considerate of Madrid on the matter eased. After Spain and America had fully ratified the Adams-Onís Treaty in February 1821 and a liberal government came to power in Madrid, Monroe proposed to the Senate on March 8, 1822 the diplomatic recognition of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, Mexico , Chile , Peru and Colombia . The special importance of the diplomatic recognition of the South American republics lay in two aspects: on the one hand, it sparked a political discussion about the continuation of colonialism ; on the other hand, it redefined the basis of relations between America, Europe and the western hemisphere . To a lesser extent, this move raised the question of how far the United States should play an active role in European affairs.

Indian policy

Monroe was the first President to visit the American West and, in his cabinet, entrusted War Minister Calhoun with departmental responsibility for this region, which included border security and Indian policy . In order to prevent the relentless attacks on the settlement areas of the Indians associated with the steadily advancing westward expansion, he advocated dividing the areas between the federal territories and the Rocky Mountains and assigning them to different tribes for settlement. The districts should each receive a civil government and a school system. In a speech to Congress on March 30, 1824, Monroe spoke out in favor of relocating the Indians living on United States territory to lands beyond the western border where they could continue their ancestral way of life. Overall, he appealed that in dealing with the Indians, humanitarian considerations and benevolence should prevail. Nevertheless, he shared in principle Jackson and Calhoun's reservations about sovereign Indian nations, since they were an obstacle to the further development of the West. Like Washington and Jefferson, he wanted to confront the Indians for their own good with the advantages of American culture and Western civilization, also in order to save them from extinction. Hence, Monroe's rhetoric about independent Indian nations, which had been the bedrock of American Indian policy until the 1812 War, was paid lip service.

Missouri Compromise

With the establishment of the United States, the admission of new states was always connected with the slave question . Between 1817 and 1819 Mississippi , Alabama, and Illinois had been recognized as new states. The rapid expansion showed an increased economic gap between the regions and a shift in power in Congress to the disadvantage of the southern states, which therefore saw their plantation economy, which is dependent on slavery, increasingly threatened. In addition, at this time, growing resistance to slavery began to form in the northern states . When Missouri asked for admission to the American Union in 1819 , the question of admission conditions led to the first violent clash between opponents and supporters of slavery and the entire country being split into two hostile camps.

To what extent Monroe lived up to his presidential leadership role in working out the Missouri Compromise is still controversial today, with the majority of historians emphasizing Monroe's passivity. He looked at the question of reception conditions less from a moral than from a political perspective. What was unusual was that Monroe did not call a cabinet meeting on this matter, as was his usual way of dealing with pressing issues. He probably wanted to avoid a confrontation between the staunch abolitionist Adams and the cabinet members from the slave states . Privately, Monroe made it clear that he was vetoing any law that dictated Missouri a certain stance on the slave issue as a condition of admission. Secretly, Monroe knew from Virginia politicians in Congress that confidential discussions were taking place there about drawing a compromise line west of Missouri at 36 ° 30 ′ latitude. Future states north of this line should be slave-free, while those south of it should be free to decide for themselves. Monroe himself was a slave owner and, like Jefferson, felt morally torn on this issue. His scruples did not go beyond the conventional view of educated Virginians of the late 18th century that slavery was an evil and should eventually be ended.

After this compromise was presented in the Senate, Monroe quietly indicated that he would sign any law based on that agreement. When this became known in his native Virginia, the local political establishment reacted with indignation. In a letter to Jefferson at the beginning of 1820, Monroe described the Missouri question as the most dangerous for the cohesion of the American Union that he had encountered so far. To organize the majority in Congress, Monroe activated Adams as well as Crawford and Calhoun, who were to use their political influence in the New England and Southern states. On February 26, 1820, the Missouri Compromise was finally passed in Congress. In March, Monroe presented the legislative proposals that set the compromise line and left Missouri free to decide on slavery for itself, while Maine was accepted into the union as a slave-free state to compensate. The cabinet unanimously agreed that Congress had constitutional legitimacy to prohibit slavery in territories and future states. Monroe was warned by friends and son-in-law Hay that the mood in the southern states could turn in favor of another candidate in the upcoming presidential election .

Trade policy

In the dispute over the introduction of protective tariffs, regional differences emerged that were similar to those of the Missouri Compromise. While the Central Atlantic and New England states advocated a significant increase in the protective tariffs, which were mainly directed against England and were set in 1816, in order to protect domestic manufacturing , the southern states strongly opposed it. Since England was the most important sales market for their cotton , they feared for their economic existence if this trade relationship was seriously impaired. In the speech on the occasion of his second inauguration in 1821, Monroe avoided any determination on this question. In the following year he advocated better protection for American manufactories in moderate terms. In the spring of 1824 the dispute intensified, with the upcoming presidential election campaign playing an important role.

Economic crisis of 1819 and budgetary policy

At the end of his first term in office, the economic crisis of 1819 broke out. During this economic and financial crisis , exports collapsed, there were loan and bank defaults and a rapid decline in property values . As a result, cuts in the state budget had to be made in the following years , mainly affecting the defense budget , which the conservative Republicans had watched with horror anyway, to over 35% of the total budget in 1818. As a result, there was friction in the cabinet when Treasury Secretary Crawford, who had seen himself as the natural successor of Monroe since his narrow defeat in the decisive caucus in the presidential election in 1816, took the opportunity to cut departments at his rival Calhoun. Clay joined the alliance of Crawford and Conservative Republicans, which was primarily concerned with the removal of the network of military forts that Monroe and Calhoun had created in the Louisiana Territory . Clay, who came very close to this goal, saw private trade interests threatened by the military posts. While Monroe's fortification program survived the cuts unscathed, the target size of the standing army was reduced from 12,656 to 6,000 in May 1819. The next year the president's favorite project hit and the budget for strengthening and expanding the forts was cut by over 70%. In 1821, the defense budget was reduced to 5 million US dollars, roughly half that of 1818 . When the austerity measures went so far as to remove Jackson the rank of general , Monroe reacted ashamed and appointed Jackson military governor of the Florida Territory .

Transport policy

The western expansion and increasing internal trade between the southern states, the northeast and the new states brought the establishment of national transport routes on the agenda, which was the focus of the first two years of Monroe's presidency. The political discussion centered on the question of the connection between the east coast and the Ohiotal west of the Alleghenies. In the last year in office, Madison had vetoed a law due to constitutional concerns that was supposed to finance the construction of such traffic routes with federal funds via the Second Bank of the United States , and previously called for the creation of a constitutional basis by passing corresponding amendments . Clay, who was the most important advocate of Western states in Congress, opposed this view. Even so, Monroe vetoed when Congress decided to fund improvements to the Erie Canal with federal funding. Although he recognized the need for national transport infrastructure projects , including military mobilization , like Madison, he saw them as a matter for the individual states. In the middle of his first term in office, Monroe successfully drafted a compromise formula in a veto message against the introduction of a toll on the National Road , which linked the Potomac and Ohio Rivers. Accordingly, while Congress had no right to build or manage interstate traffic routes, it could approve funds for them. The use of federal funds was tied to the obligation that they served the common defense and welfare of the nation and not just that of a single state. Washington was then able to finance infrastructure measures without interfering too deeply with the rights of the individual states.

Presidential election 1820

Monroe announced his candidacy for a second term early. At the Republican caucus on April 8, 1820, the 40 members unanimously decided not to run a candidate against Monroe. The federalists did not run their own presidential candidate. Monroe's re-election therefore produced the clearest Electoral College result in American history, behind the unanimous election of Washington as President in 1789 . Only one of the 232 electors , former New Hampshire Governor William Plumer , voted against him and for Secretary of State Adams, who did not run. As a reason, Plumer stated, among other things, that he wanted to prevent Monroe from becoming president like the great Washington without a dissenting vote. Even ex-President Adams voted as the leader of the Massachusetts electors for his former, bitter political opponent Monroe. In addition to the lack of opposition, this undisputed victory of Monroe was due to his successful efforts to overcome orthodox republican dogmata and thus to open up his party. This broad consensus did not survive Monroe's presidency, and in the next presidential election personal arguments and conflicts between interest groups determined what was going on. These intra-party tensions replaced the differences between republicans and federalists of the first party system , which stemmed from different philosophical views . Despite this widespread support in the presidential election, Monroe had few loyal supporters and accordingly little influence in the 17th Congress of the United States, which was elected in parallel .

Monroe Doctrine

In January 1821, in a conversation with the British ambassador Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe , Adams expressed the idea for the first time that the American double continent should be closed to further colonization by foreign powers. It is not clear whether Adams was the originator of this idea or whether others, including Monroe, came up with it independently at around the same time. According to Hart, the increasing self-confidence of the United States resulting from this guiding principle would have been difficult to imagine without the conclusion of the Adams-Onís Treaty. During the negotiations on the border disputes in the Oregon Country, Adams expressed the principle to the British and Russian ambassadors in the summer of 1823 that the further settlement of America, with the exception of Canada, should be in the hands of the Americans themselves. The "America for the Americans" principle quickly became a kind of theological belief in the Monroe administration. After France ended the Spanish Revolution of 1820 by winning the Battle of Trocadero in August 1823 on behalf of the Holy Alliance , War Secretary Calhoun and British Foreign Secretary George Canning , a cousin of Stratford Canning, warned Monroe that European powers might be in South America intended to intervene. This increased the pressure on him to comment on the future of the western hemisphere.

In August 1823 there was a correspondence between the British Foreign Secretary , the American Ambassador in London, Richard Rush , and Adams, which followed on from his remarks to Stratford Canning about the decolonization of South America in January 1821. It was a matter of exploring a common position on a possible French intervention in South America, which Britain saw its trade interests in that region at risk. Canning had signaled that his country was willing to issue a joint declaration against recolonization and, with the Royal Navy, to thwart possible attempts by the Holy Alliance to regain the lost colonies of Spain in South America. When this correspondence, which had not led to any concrete result, was presented to Monroe in mid-October 1823, his first impulse was to accept the British offer. Not wanting to ignore George Washington's dictum not to get involved in foreign alliances, he sent the correspondence to Jefferson and Madison for advice. In doing so, he suggested to his two predecessors that in future any European interference in the affairs of South America should be viewed as a hostile act against the United States. Jefferson replied that he welcomed concerted action with Britain against European interference in South America, and he essentially summarized what would later become known as the Monroe Doctrine . Madison also advised Monroe to accept London's offer. On October 23, 1823, Rush sent a message to Adams informing him of Canning's withdrawal from the voting process on a common South American policy.

Irrespective of the rejection of a joint South America declaration by London, which Monroe probably did not reach until mid-November, the matter was discussed intensively and extensively in the cabinet from November 7th, with Adams and Calhoun playing an active role alongside the President. The occasion was the upcoming State of the Union Address, at which Monroe had to inform about the state of foreign relations in addition to domestic political issues. When Monroe asked for a summary of American foreign policy in preparation for Adam's speech, Adam suggested a paragraph of principle. The wording was that the American double continent, which had become independent, should no longer be regarded as a colonization area of European powers, with the exception of the colonies that still existed. Until mid-November, the cabinet discussed the question of whether the position on South America should be unilateral or jointly with Great Britain. After Monroe received Rush's October 23 message, he realized that London no longer considered a Holy Alliance military intervention in South America likely. On November 21, he informed the cabinet that he intended to present a doctrine on South America in the State of the Union Address . Monroe saw this matter as a unique opportunity to assert the strengths and interests of the United States and to define itself as a nation. However, the Monroe government initially lacked the means to close the discrepancy between rhetorical claims and actual influence in Latin America.

Monroe and his cabinet finally agreed to adapt the wording of the passage to two memoranda from the Foreign Minister to the Russian and British ambassadors, which were sent out shortly before the State of the Union address. To avoid possible points of attack, the president deleted a paragraph from Adams that addressed the fundamental republican principles of the United States. The dispatch to the Russian embassy was intended to underline that the main addressee of the Monroe Doctrine was the Holy Alliance. In that message, Adams made it clear that the United States, other than Spain's military effort to restore its established colonial power in South America, would not accept the interference of any other additional European power.

On December 2, 1823, Monroe finally presented the revised contribution to foreign policy in his seventh State of the Union Address. The principles, divided into three paragraphs, first came to be known as the 1823 Principles and later as the Monroe Doctrine , which, despite its importance, was never codified . Their first mention followed in a paragraph dealing with the Pacific Northwest negotiations with Russia, the next two in the context of historical relations between Europe and the United States. A total of six principles can be derived:

- The American double continent is no longer an object for the acquisition of new colonies or recolonization by Europe.

- Any European power that wishes to extend its monarchical system to an area of the western hemisphere is viewed as hostile.

- Although the United States did not want to interfere in existing colonial relations between South America and Europe, it would regard any attempt by Europe to regain colonial power over the independent republics of South America as an unfriendly act.

- As long as circumstances did not change significantly, for example through intervention by the Holy Alliance, the United States would remain neutral in the war between Spain and its former colonies in South America.

- The United States does not want to interfere in internal European affairs and in return expects the same from Europe.