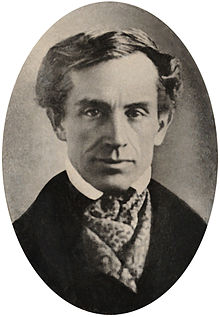

Samuel FB Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (born April 27, 1791 in Charlestown , Massachusetts , † April 2, 1872 in New York ) was an American inventor and professor of painting, sculpture and drawing. From 1837 Morse developed a simple writing telegraph ( Morse machine ) and, together with his colleague Alfred Vail, also developed an early Morse code in the form later called the Land Line Code or American Morse Code . With this, Morse created the practical requirements for reliable electrical telegraphy , as it was also used a little later.

Life

Origin and studies

Samuel Morse was the eldest son of the Calvinist clergyman and geographers Jedidiah Morse and Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese. After attending Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, he graduated from Yale College (now Yale University ). While at Yale he also attended lectures on electricity from Benjamin Silliman sr. and Jeremiah Day . He earned part of college fees by painting miniatures, which he sold for $ 5 apiece. Here he also met some of the best and brightest minds in America, such as: B. John C. Calhoun , Washington Irving, and James Fenimore Cooper . He graduated from Yale College in 1810.

Life as a painter

Soon after he graduated, he met Washington Allston , an artist who was then living in Boston and who wanted to return to England. Allston had noticed Morse's talent through the painting "Landing of the Pilgrims" and he signed a contract with Samuel's father in which he assured his son's financial support for three years. On July 15, 1811, they sailed to England with the "Lydia". Morse studied not only under Allston, but also under John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West , who was director of the Royal Academy of Arts . He remained in close ties with Allston, whom he revered his life as a master. At the end of 1811 he was accepted into the Royal Academy, where he immediately succumbed to neo-classical art, especially Michelangelo and Raphael. He studied and drew anatomy from models and produced his masterpiece: a clay model "The Dying Hercules", which is based on the Laocoon in pose and muscles . For the sculpture he received the First Prize of the Society of the Arts, a gold medal, at the Adelphi in London. In 1814 Morse painted his last classicist picture "The Judgment of Jupiter". In 1815 he returned to America.

Morse could hardly make a living from his painting. He received only $ 15 for a portrait. Lacking both institutional and private sponsorship, the American art scene was forced to adapt his grandiose plans, and he soon realized that portraiture was the only lucrative genre.

Among those portrayed by him was, for example, Nathan Smith (1762-1829), the first surgery professor at Yale University .

Morse's portrait by John Adams

Samuel FB Morse's relentlessly factual portrait of former President John Adams was both the result of an important commission from leading publisher Joseph Delaplaine (1777–1824) in Philadelphia and the cause of one of the artist's first professional disappointments.

When Morse returned to Boston from London in the fall of 1815, he was confident that his successful studies at the Royal Academy would confirm his future success in America. Prior to his arrival, he had stated in a letter to his parents that he planned to start painting portraits immediately, for a fee forty dollars less than Gilbert Stuart's . So he would earn enough to return to England with more important assignments in his hands within a year. Circumstances were tougher than expected, but over time the young artist received offers from several commissions from Delaplaine. In addition, his well-connected father and his connections had already announced on behalf of his son John Adams that he would like to paint a portrait of him.

As early as the summer of 1814, Joseph Delaplaine had begun advertising a series of illustrated books with the title Delaplaine's Repository of the Lives and Portraits of Distinguished American Characters with an extravagant brochure . He envisioned the project at a substantial profit and therefore intended to pay very little for the original portraits on which his engravings would be based. Partly as a favor to Morse's father, John Adams reluctantly undertook to sit for the portrait, commenting, "It doesn't seem worth the effort to paint a bald head that has eighty winters snowed on."

Morse apparently finished the portrait in a relative hurry while staying at Adams' house, because on February 10, 1816 Abigail Adams had said about the portrait: "a strict, unpleasant resemblance". Shocking in its directness and honesty, it was an improvement over other early portraits by Morse, which had conveyed neither substance nor the physical vitality of his models. The determination with which Morse documented the deep wrinkles and sagging flesh, the uncaring stare and pinched, involuntary grimace of the elderly Adam was surely unexpected. Adams' own reaction to Morse's portrait is not recorded.

Delaplaine's reaction was quick and negative; he immediately tried to convince Adams of the shortcomings of the portrait and tried in vain to gain access to the portrait of Gilbert Stuart by Adams. In his rejection of the portrait, Delaplaine cited harsh criticism from the artist's peers and stated his intention to withhold payments to Morse. Humiliated and frustrated by Gilbert Stuart's domination of the portrait market, Morse had temporarily given up his artistic work that summer.

How poor Morse was at that time is shown by an incident told by General David Hunter Strother of Virginia, who was taking drawing lessons with Morse: “I paid him the money for the lessons and we had dinner together. It was a simple but good meal, and after Morse finished he said, ' This is my first meal in 24 hours. Strother, don't become an artist. It means begging. Your life depends on people who don't understand anything about your art and don't care about it. A domestic dog lives better, and only the sensitivity that drives the artist to work keeps him alive to suffer. '“

The House of Representatives

After roaming New Hampshire and Vermont as a traveling portrait painter, he lived in Charleston, South Carolina for a while and eventually settled in New York City. For Morse, however, portraiture exemplified American materialism. Like Sir Joshua Reynolds , he saw the historical painting as the ultimate expression of art. He followed in the footsteps of his compatriots Benjamin West and John Trumbull and modernized the historical representation for an American audience in 1823 with the painting "House of Representatives". It includes custom portraits of dozens of Congressmen, Supreme Court judges, journalists, and house servants who served in a Democratic government .

In 1825 Morse was commissioned to portray the freedom hero Lafayette. The best portrait painters of his time applied for this job. He was finally successful. The full-length portrait of the aging hero Lafayette shows him in front of a flaming evening sky. With its romantic pathos and its rather sober drawing, the picture represents a high point of portrait art in America at the time. Morse received $ 700 for the portrait and also received half of the sales proceeds of an engraving that Asher Durand had made from the picture. The news of his wife's death depressed him heavily, especially since it only reached him after his wife had already been buried.

In 1825, Morse pioneered the New York Drawing Association and was one of the founders of the National Academy of Design in New York the following year ; he also became its first president (1826-1845). Here he also gave his lectures on painting, the first in 1826 ("Lectures on the Affinity of Painting with the Other Fine Arts").

Gallery of the Louvre

In 1829 he sailed to Europe and toured England, France and Italy. He visited Paris and the Musée du Louvre for the first time. After a trip to Italy he came back to Paris and began his painting "Gallery of the Louvre" in September 1831, which he finished a year later with the "European" part and returned to America in November 1832. A cholera epidemic had broken out in Paris , which caused many residents to flee the city. Morse had stayed and defied danger to complete his masterpiece. The arrangement on the walls consists of around 40 exquisite miniature copies of the works of Raphael , Leonardo da Vinci , Titian , Antonio da Correggio , Nicolas Poussin , Peter Paul Rubens , Anthonis van Dyck and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo as well as other artists. From February to August 1833 he finished his painting and exhibited it in New York and New Haven, Connecticut. He had placed himself in the center of the picture, apparently helping his daughter Susan with copying. Also shown are: C. James Fenimore Cooper in the door frame, on the left in the corner his wife Susan with daughter, in the front left in the picture F. Richard W. Habermas , artist and roommate of Morse, and Horatio Greenough , artist and roommate. At the front right one suspects the picture of Morse's deceased wife Lucretia Pickering Walker. The exhibitions met with critics, but they were a financial failure. In August 1834 he sold the “Gallery of the Louvre” and its frame for $ 1,300 to George Hyde Clark. The painting was on loan to Syracuse University in New York, which bought it in 1884. Now Morse’s wish was finally fulfilled that his painting would be used for learning by American artists who could not afford a trip to Europe. (In 1982 it was acquired by Daniel J. Terra for the collection of the Terra Foundation for American Art .)

Professor at New York University

In the same year he was appointed first professor of art history at New York University . In the newly built university building in neo-Gothic style on Washington Square East, Morse moved into the Northwest Tower as a studio and six additional rooms for his students, who received both practical and theoretical lessons. As an unpaid faculty member, he collected tuition fees directly from his students.

On the return journey in the autumn of 1832 on the SS Sully from Le Havre to New York, Charles Thomas Jackson , who had studied with Claude Servais Mathias Pouillet in Paris , entertained the passengers with his electrical devices, such as an electromagnet from Hippolyte Pixii and galvanic cells . The use of electricity for signaling was discussed.

Around the same time, Morse began to be interested in chemical and electrical experiments. In 1837 he built the first Morse Code machine from wire scraps, scrap metal and his wall clock , which he first demonstrated on September 4, 1837. Alfred Vail was present at this demonstration .

In 1837 he was passed over by the Congress when the contract was awarded to paint the rotunda. That struck Morse deeply, and that was the year he painted his last work of art.

Works (selection)

- Susan Walker Morse (The Muse) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

- Some of Samuel FB Morse's paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

- Painting by Samuel Morse in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Portrait of Maria Lucrezia Walker Morse, painted 1819 , in the Mead Museum at Amherst College

Political activities

Coming from a white, Anglo-Saxon and strictly Protestant family, Morse cultivated nativist , xenophobic convictions and tended towards the Know-Nothing Party with its anti-Catholic conspiracy theories . In Morse's eyes, Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany in particular posed a threat to the United States because, as supporters of the Pope, they would try to usurp power in the country. In 1835 he published the polemical book Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration . In it he called for all immigrants to be denied the right to vote. He himself ran unsuccessfully for the office of mayor of New York. The later development of the Morse code arose from his desire to provide the government with a secret script in the event of a Catholic uprising, with which it could communicate covertly. Later, however, he came to the conclusion that the public use of the telegraph was conducive to the growing together and thus the strengthening of the USA. In it he succeeded his father Jedidiah Morse, who had written his work American Geography , published in 1789, expressly with the aim of promoting the still weak national feeling of the Americans.

Life as an inventor

Since Morse was a professor of painting and sculpture, it is not surprising that his first telegraph was made from an easel . A pendulum was hung from the frame with a pin. Below the pendulum, a clock mechanism pulled a rolled strip of paper. As long as there was no current flowing through the electromagnet, the pen drew a straight line. But as soon as electricity flowed, a magnet attracted the pendulum and a V-shaped jagged shape appeared on the paper. Each point represented a number. At the first demonstration, the strip of paper read: “214-36-2-58-112-04-01837”. That meant a successful attempt with Telegraph September 4th 1837 . The first electromagnetic telegraph was invented and built by Carl Friedrich Gauß and Wilhelm Eduard Weber in 1833 , and they also sent the first telegram. The first usable telegraph was designed by Carl August von Steinheil in 1836 .

These first attempts were seen by the student Alfred Vail , who became a technically skilled Morse operator and persuaded his father to invest $ 2,000 in development work. As early as September 23, 1837, he had formed a partnership with Vail, which obliged them to build a number of telegraph instruments at their own expense and to file patents for them. In return, Morse guaranteed Vail ¼ of the revenue from patents in the United States and half of those abroad.

Morse found that his sporadic attempts to work with batteries, magnets, and wires didn't get him much closer to understanding electricity. So he asked a colleague at New York University, Professor Leonard D. Gale, for help . He was a professor of chemistry and familiar with the work of Joseph Henry , an electricity pioneer at Princeton. Henry had made a distant bell ring by opening and closing an electrical circuit. As early as 1831 he had published an article, unknown to Morse, in which he toyed with the idea of an electric telegraph. Gale's knowledge of this article and his help not only corrected flaws in the system, but also showed Morse how to use a relay system invented by Joseph Henry to amplify the power of the signal and solve distance problems. Henry's experiments, Gale's help, and Alfred Vail's skill were the keys to Morse's success.

Under Vail's influence, Morse abandoned the numeric code. There were now short and long pendulum deflections on the strip of paper. Without the connecting lines, this was the later Morse code composed of dots and lines. It was sent with a contact board in which short and long copper plates were inserted. If you then ran an electrically conductive pen over the plate next to a letter, a short or long current surge was induced in the line . So the telegraph operator at the transmitter didn't necessarily have to learn the code by heart. This system was successfully demonstrated to the public on January 6, 1838, by Morse and Vail.

After five years of experimentation, Morse was able to patent his device . The United States Patent Office issued the certificate to him on June 20, 1840.

At the same time, the US Congress was looking for a suitable system of optical telegraphy . Morse also demonstrated his telegraph to the Cabinet. Morse asked President Martin van Buren to whisper a short sentence in his ear to broadcast. Morse looked in his “register”, in which he had noted the approx. 5,000 most frequently used words and assigned numbers to them. He started the transfer while dots and lines appeared on a strip of paper at another table. When the transmission was finished, the assistant began to translate the code into numbers and then to search for the words in his “lexicon”. Then he announced the received message "The enemy is near". Those present were thrilled.

The congressmen appeared unwilling to approve the required amount of $ 30,000. Only the chairman of the trade committee, Francis Ormond Jonathan ("Fog") Smith from Maine, immediately recognized the enormous possibilities of the telegraph. He was preparing a bill, even though he knew that it had little chance at the time. He expressed his desire to become a partner in Morse’s company, although that was a conflict of interest with his mandate. Morse agreed, realizing that he needed a sponsor familiar with Washington's intrigues - and another source of cash. Vail and Gale agreed for the same reasons. Smith was supposed to provide legal assistance and finance a three-month trip to Europe for Morse and himself to acquire patent rights in Europe. They signed a corresponding agreement on March 2, 1838. Morse remained the main shareholder. Smith's share was 5/16, Alfred and George's was reduced to 3/16 each. Nonetheless, Alfred went to Speedwell to make two instruments for Morse's European trip.

In this situation, Morse traveled to Europe in May 1838 to find support there. He was unsuccessful there either, but could at least study the European competitive systems. Morse was received with appreciation by scholars in every country he traveled and he exhibited his apparatus under the auspices of the Académie des Sciences in Paris and the Royal Society in London, respectively. He received a patent in France that was practically worthless because it required the inventor to put his discovery into operation within two years. In addition, telegraphs were under government control and private companies were excluded. After nearly a year of absence, Morse returned to New York in May 1839 and wrote to Francis OJ Smith that he had returned without a penny in his pocket and that he even had to beg for his meals. What was worse for him was that rent debts had accumulated in his absence. Four years of worry and abject poverty followed. He lived from the drawing lessons he gave some of the students and commissioned portraits.

After returning home, the device was modified so that the pen no longer touched the paper when it was in rest position. Only when the electromagnet pulled the pen did it mark a point or a line on the strip of paper, depending on the duration of the current flow. Decades later, Morse's colleague Alfred Vail discovered that the characters could also be deciphered acoustically and did not necessarily have to be recorded on a strip of paper.

In 1839 Morse met Louis Daguerre , the inventor of the daguerreotype , in Paris and published the first American description of this photographic process. Morse became one of the first Americans to be able to take a daguerreotype photograph. He opened a photography studio in New York with John William Draper and taught a number of students, including Mathew Brady , who later became a civil war photographer .

Meanwhile, his British rivals Charles Wheatstone and William Cooke were getting significant government aid with their needle telegraph in England, and they made every effort to convince Congress to apply their systems in America while Morse struggled to get his own countrymen off the ground To convince the advantages of his system.

In October 1842, Morse experimented with underwater transmissions. Two miles of cable were sunk between The Battery and Governors Island in New York Harbor and signals were successfully sent. Then a ship with its anchor damaged the cable and the experiment was ended.

The Washington - Baltimore test route

On March 3, 1843, Congress approved $ 30,000 to build the 60 km long telegraph line from Baltimore , Maryland , to Washington D.C. Construction began a few months later. With the finance minister's approval, Morse appointed Professors Gale and Fisher as his assistants, and Alfred Vail was there again. James C. Fisher oversaw the manufacture of the cable, its insulation, and its insertion into the lead pipes, while Vail oversaw the magnets, batteries, and other essentials, including acid, ink, and paper. Gale was available when his advice was needed, and FO Smith signed contracts with the companies digging the trench next to the railway line.

FOJ Smith was able to win the collaboration of Ezra Cornell , who constructed a machine that dug a trench for the cable to be laid in lead pipes. Morse had looked at them and agreed to their use. Cornell acted as Morse's "assistant" and received $ 1,000 a year for it. In October 1843, Cornell began laying the telegraph cables. The insulation on the wires had been scratched when it was inserted into the lead pipes. Fisher was responsible for this failure because he failed to check the cables before inserting them into the lead pipe. Morse then ended the collaboration with the supplier of the pipes, the Serrell company. That created a lot of trouble, as Morse wrote to his brother Sidney. Morse ordered the work to be stopped immediately. Cornell again built a machine that pulled the wire out of the pipes and re-insulated it. On December 27, 1843, Morse informed the Treasury Secretary that he had fired Fisher. Gale had given up the collaboration for health reasons, so that Morse could only rely on Vail.

Morse asked Cornell to leave the work on hold until he had an idea how to solve the problem. In addition, none of it should leak to the public. Cornell spent the winter in Washington reading books on electricity and magnetism in the Patent Office and Library of Congress. His reading convinced him that the underground installation was useless and the wires should be attached to posts above ground with glass insulators. Morse agreed.

In the spring of 1844 they began to build the cables above ground on telegraph poles. On May 24, 1844, Samuel Morse telegraphed the first electronic message using his Morse alphabet via this line. The content of the message was: "What hath God wrought" (What God has done?) ( Num 23:23 EU ). Samuel Morse sent from the Supreme Court room in the Capitol and Alfred Vail acknowledged receipt at the Baltimore train station.

Morse saw the telegraph as a natural accessory to the mail and put his patent up for sale by the government for $ 100,000. President James K. Polk was delighted with the telegraph, but it needed Congressional approval. The Postmaster General, Cave Johnson , feared the cost of upkeep. American telegraphy came into the hands of private investors. In the spring of 1845, Morse chose Amos Kendall , the former Postmaster General, as his agent. Vail and Gale agreed. In May, Kendall and FOJ Smith formed the Magnetic Telegraph Company and expanded the telegraph line from Baltimore to Philadelphia and on to New York.

In 1847 Morse acquired the Locust Grove country estate in the Town of Poughkeepsie in the Hudson Valley , which was designed by the architect Alexander Jackson Davis and which he used as a summer residence until the end of his life. A short time later he bought a house on New York's 22nd Street, where he spent the winter months. After his death, a marble sign was attached to the house that read: “In this house SFB Morse lived for many years and died.” (SFB Morse lived in this house for many years and died. )

A court ruled in 1853 that all American companies using telegraphy had to pay license fees to Morse . From 1857 to 1858 Morse advised Cyrus W. Field as an engineer on the laying of the first transatlantic cable. However, the undertaking failed. In 1859 his Magnetic Telegraph Company was merged into Fields American Telegraph Company . In 1865, Morse was one of the founders and trustees of Vassar College . From 1866 to 1868 he lived with his family in France and represented the USA at the 1867 World's Fair in Paris.

Samuel Morse died in 1872 and was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery .

family

On September 29, 1818 Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker (born November 14, 1798) in Concord, New Hampshire. They had three children together:

- Susan Walker Morse (born September 2, 1819, † 1885) married Edward Lind in 1839 and moved to Puerto Rico to his sugar cane plantation. Lind died in 1882. In 1885, Susan intended to return to New York forever, but tragically fell overboard at sea.

- Charles Walker Morse (March 7, 1823, † 1887) married Manette Antill Lansing on June 15, 1848. They had four children.

- Edward James Finley Morse (January 17, 1825 - 1914)

Lucretia died on February 7, 1825 at the age of 26 after the birth of her third child. The children grew up with relatives.

Morse's father, Jedidiah Morse, died on June 9, 1826, and his mother, Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese, on May 28, 1828.

On August 10, 1848, Morse married Sarah Elizabeth Griswold, in Utica, New York, who had been the bridesmaid at the wedding of his son Charles. She was 26 years old, deaf from birth, and two years younger than his daughter Susan. They had four other children:

- Samuel Arthur Breese Morse (* July 24, 1849; † 1876), unmarried.

- Cornelia (Leila) Livingston Morse (April 8, 1851 - 1937), married the pianist Franz Rummel, Jr. (November 1, 1853 in London; † May 2, 1901 in Berlin). Son Walter (born July 19, 1887 in Berlin) was also a pianist. Her mother died with her in Berlin on November 14, 1901.

- Goodrich William Morse (born January 31, 1853 - 1933), married Catherine Augusta (Kate) Crabbe.

- Edward Morse Lind (March 29, 1857 - 1923) became a painter like his father. He married Charlotte Dunning Wood on July 24, 1884. After her death in 1888, he married Clara Lounsberry on October 16, 1899.

honors and awards

Morse was showered with honors from around the world: in 1848 his alma mater, Yale College, awarded him an honorary doctorate, and then he was made a member of almost all American science and art academies, including the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1849 .

He has received more honors from European governments and scientific and art societies than any American before him. In 1848 he received the diamond medal "Nishaun Iftioha" from the Sultan of Turkey. Gold medals for scientific merit followed from the King of Prussia, the King of Württemberg and the Emperor of Austria. The gift from the Prussian king was embedded in a solid gold snuffbox.

In 1856 Morse received the Knight's Cross of the Legion of Honor from Emperor Napoleon III. In 1857 he was appointed a Knight of the Order of Dannebrog by the Danish King and in 1858 the Queen of Spain sent him the order "Cross of Knight Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic". In 1859 the representatives of various European powers met in Paris to discuss at the instigation of Emperor Napoleon III how they could best express their gratitude to Professor Morse. France, Russia, Sweden, Belgium, Holland, Austria, Sardinia, Tuscany, Turkey, and the Holy See (the Vatican) were involved. They agreed to give Professor Morse, on behalf of their united governments, the sum of 400,000 francs as a fee and personal recognition of his work.

In 1856 the Telegraph Companies of Great Britain held a banquet in London in honor of Morse, chaired by William Fothergill Cooke , who was himself a respected inventor of the telegraph system.

In 2002 the asteroid (8672) Morse was named after him.

Publications

Morse has published poems and articles in the North American Review.

- as editor: Amir Khan, and other poems: the Remains of Lucretia Maria Davidson (New York, 1829), "to which he added a personal memoir"

- Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States (1835) originally published in the "New York Observer"

- Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration, and the Present State of the Naturalization Laws, by an American , originally as a contribution to the Journal of Commerce, 1835

- anonymously he published in 1854: Confessions of a French Catholic Priest, to which are added Warnings to the People of the United States, by the same Author ("edited and published with an introduction", 1837)

- Our Liberties defended, the Question discussed, is the Protestant or Papal System most Favorable to Civil and Religious Liberty? (1841)

literature

- Samuel FB Morse; His Letters and Journals . Vol. I. Publisher: Houghton Mifflin company Boston and New York, 1914 Edited and Supplemented by his son: Edward Lind Morse

- Samuel FB Morse; His Letters and Journals . Edited and supplemented by his son Edward Lind Morse. Volume II

- Samuel Irenæus Prime: Life of Samuel FB Morse, LL.D., inventor of the electro-magnetic recording telegraph Publisher: D. Appleton & Co., New York 1875

- Margit Knapp: Overcoming slowness. Samuel Finley Morse - the founder of modern communication. Freytag-Berndt, 2012.

- Christian Brauner (Ed.): Samuel FB Morse. A biography. Birkhäuser, Basel, Boston, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-7643-2488-0 .

- Oona Horx-Strathern: The visionaries. A little story of the future - from Delphi to today. Signum, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-85436-402-3 , p. 47.

- Kenneth Silverman : Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel FB Morse . Publisher: button; First Edition (October 21, 2003) ISBN 978-0-375-40128-2

- Carleton Mabee: The American Leonardo: A Life of Samuel FB Morse . Publisher: Purple Mountain Pr Ltd; Rev Sub edition (May 2000) ISBN 978-1-930098-08-4

- Richard R. John: Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse . Publisher: Harvard University Press, 1998 ISBN 978-0-674-83342-5

- Tom Wheeler : Mr. Lincoln's T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War . Publisher: Harper Collins Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-06-112980-1

Web links

- Literature by and about Samuel FB Morse in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Samuel FB Morse at Zeno.org .

- U.S. Patent Number 1,647 to Samuel Morse's Telegraf

- Saturday, June 10th, 1871 was the day selected for the celebration. Morse's last message: “Thus the Father of the Telegraph bids farewell to his children”. A version of this article was originally published in the February, 2001 issue of "The OTB", the quarterly journal of "The Antique Wireless Association".

- Field Telegraph Station in Virginia in 1864 - Civil War Telegraph Station

- Morse Timeline 1840–1872 Timeline - The Samuel FB Morse Papers at the Library of Congress

- Samuel FB Morse . Bronze bust 1870 by Byron M. Pickett (1834–1907)

- Samuel Morse FB in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Individual evidence

- Source: Malone, Dumas, ed Dictionary of American Biography . Publisher: Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1943, Volume XIII, Samuel Morse, pages 247-250.

- ^ Biography Samuel FB Morse (1791–1872) in The Encyclopedia

- ↑ Landing of the Pilgrims ( Memento of the original from April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Sculpture of "The Dying Hercules" at Yale University Art Gallery ( Memento of the original from April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Medal for the Model of the Dying Hercules ( Memento of the original from April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Barbara I. Tshisuaka: Smith, Nathan. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1340.

- ↑ Prospectus of Delaplaine's national Panzographia, for the reception of the portraits of distinguished Americans (1818) - on page 15 the notable personalities are listed.

- ↑ Adams painted by Gilbert Stuart ( Memento of the original from April 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Portrait of John Adams ( Memento of the original from April 24, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 1816. Oil on canvas (75.5 cm × 63.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, New York.

- ^ Drawings of David Hunter Strother

- ^ The Communication Revolution. Samuel Morse & The Telegraph By Mary Bellis

- ↑ General Lafayette and The House of Representatives and other paintings by Morse

- ↑ nationalacademy.org: Past Academicians "M" ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on June 3, 2015)

- ^ Gallery of the Louvre ( Memento of April 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) - Interactive painting animation by Taylor Walsh

- ^ Gallery of the Louvre ( Memento of April 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) - Interactive painting animation by Taylor Walsh

- ^ New York University - Samuel FB Morse the painter

- ^ New York University - History

- ↑ The Rotunda of the US Capitol was painted in the true fresco technique by Constantino Brumidi in 1865

- ↑ Jill Lepore : These Truths. History of the United States of America , CH Beck, Munich 2019, p. 265

- ^ Jill Lepore: This America. Manifesto for a Better Nation , CH Beck, Munich 2020, p. 31

- ^ Wording of the contract dated September 23 between Morse and Vail. Vail was 30 and Morse was 46 years old.

- ↑ Samuel FB Morse papers homepage

- ↑ 175 years “Morse code” - it started with 18 digits ( page can no longer be accessed , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Funkamateur (Magazin), September 4, 2012, accessed April 29, 2014.

- ^ Leonard Dudley: Information Revolutions in the History of the West , p. 161 Ed .: Edward Elgar Publishing 2008, ISBN 978-1-84720-790-6 .

- ^ Morse papers - sharing ownership with Smith

- ^ Invention of the Telegraph ( Memento from November 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Morse in “The Daguerreian Society” ( Memento of May 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Samuel Morse Photograph by Mathew Brady

- ↑ Ezra Cornell 1843/44

- ^ Morse - His Letters and Journals - page 211 ff.

- ↑ Drawing of the telegraph posts ( memento of the original from October 6, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. The Samuel FB Morse Papers at the Library of Congress. Bound volume - 10 June – 21 October 1844 (Series: General Correspondence and Related Documents)

- ^ Samuel FB Morse House, Poughkeepsie, New York (perspective and plan) by Alexander Jackson Davis 1851

- ^ The Samuel FB Morse Historic Site

- ^ A Brief Guide to Vassar's Charter Trustees (Morse 1861–1872)

- ^ Books for the world exhibition at the University of Heidelberg

- ^ Samuel FB Morse in the Find a Grave database

- ↑ James Edward Finley Morse at findagrave.com

- ^ Morse Family Tree in the Library of Congress

- ↑ Franz Rummel (1853–1901) ( Memento of May 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Walter Rummel (composer, arranger, piano)

- ^ House History of Washington

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 47164

- ^ North American Review in the Encyclopædia Britannica

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Morse, Samuel FB |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Morse, Samuel Finley Breese |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American inventor and professor of painting, sculpture and drawing |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 27, 1791 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Charlestown |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 2, 1872 |

| Place of death | new York |