Martin Van Buren

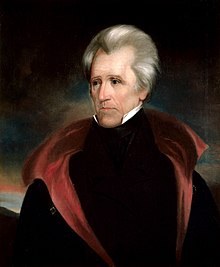

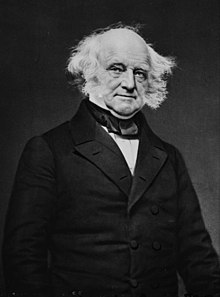

Martin Van Buren (born December 5, 1782 in Kinderhook , Columbia County , New York ; † July 24, 1862 ibid) was from March 4, 1837 to March 4, 1841 the eighth President of the United States and with Andrew Jackson the founder of modern democrats .

Van Buren was born in rather simple circumstances and grew up in a strongly Dutch environment. He learned the legal profession without having enjoyed any academic training. In the 1810s he was State Senator in New York and from 1821 a member of the United States Senate . During this time he created an influential patronage and clientele system with the Albany Regency party machine (German: "Albany Regentschaft") . In the presidential election in 1828 he was the main architect of the Jackson victory, whom he served as Secretary of State , Ambassador to London and most recently as Vice President . He played a key role in founding and building the Democratic Party in the 1830s and was one of the most important advisors to the President in the so-called kitchen cabinet .

Van Buren was the first natural born citizen as president after his successful election in 1836 . The term of office was overshadowed by the devastating economic crisis of 1837 , which he was blamed for and which he could not compensate for by foreign policy successes in relations with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and France . Van Buren's economic countermeasures also faced opposition in Congress and remained ineffective after they were passed . He took no clear position on the slave issue , which was increasingly polarizing the nation, while continuing Jackson's brutal Indian policy towards the Five Civilized Tribes on the Path of Tears .

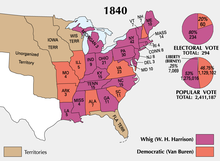

In the presidential election in 1840 Van Buren was defeated by the Whigs candidate , William Henry Harrison . After a promising comeback in 1844, he was long considered the most promising candidate for nomination as a Democratic presidential candidate, but his rejection of the annexation of the Republic of Texas was his undoing. In the presidential election in 1848 he was a candidate for the Free Soil Party without being able to win electoral votes in a state . As an elder statesman , he devoted himself to his autobiography without being able to complete it before his death in 1862.

Life

Family and education

Van Buren was born on December 5, 1782 as the third of five siblings of Abraham van Buren (1737-1817) and Maria van Alen (1747-1818) in Kinderhook in Upstate New York, south of Albany . Van Buren's family came from the Republic of the Seven United Provinces through both parents and had not been married to Americans of other ethnic origins for five generations, which is why Van Buren is to this day the only president apart from John F. Kennedy who had no English ancestors. The upper Hudson Valley at that time was still very colonial and less democratic than most other regions of the young United States: Political participation, social status and economic success depended on the property owned by a few families such as the Livingstons and Van Rensselaers split up. In this rigid hierarchical social order of the Hudson Valley, Kinderhook was one of the few places that was not owned by this power elite. The Dutch Americans presented here continues to be the majority of the population, while in the state are increasingly coming from England Civil dominated. The peculiar local color of Kinderhooks inspired the writer Washington Irving , who lived here for some time in 1809, and can be found in the stories Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow .

The mother, Maria Van Alen, a 29-year-old widow with three children, married his father, Abraham Van Buren, in 1776, who was ten years her senior. This marriage resulted in first two daughters and then three sons, of whom Martin Van Buren was the eldest. The Van Burens descended from Cornelis Maessen, who emigrated from Buren in Gelderland to the Dutch colony of Nieuw Nederland in 1631 and bought land not far from Kinderhook. In 1780, seven Van Buren families lived in the township , not least because relatives had married in the past. In Kinderhook, the common language was Dutch , which became the mother tongue of the future president. The services in the Dutch Reformed Church in the village were also celebrated in this language. Abraham Van Buren was a small farmer and part-time captain in the local militia and later forced to convert the farmhouse into a pub in order to be able to provide for the family. The family had six slaves, which was not unusual for the area, but in Kinderhook they belonged to the lower middle class at best. Abraham Van Buren increasingly had to struggle for economic survival and was therefore unable to raise funds for the education of the children. He had been a patriot during the American Revolution and later an anti-federalist and supporter of Thomas Jefferson . In federal Columbia County, which had been a Tory stronghold during the American Revolutionary War , he was part of the opposition. Abraham Van Buren made his tavern available to the anti-federalists and later Jeffersonian Republicans or Democratic Republicans for gatherings and was a leading political actor in Kinderhook. The public house, popular as a rest stop, was packed with messengers carrying messages between the state capital, Albany , and New York City , as well as political leaders, including Aaron Burr .

During Van Buren's youth, the upper Hudson Valley transformed economically, increasingly attracting capital that was invested in new businesses or speculative businesses. Among other things, this led to the founding of the nearby Kinderhook whaling town of Hudson . In addition, settlers from New England increasingly immigrated to New York in order to cultivate land that had become free from Indians or displaced loyalists. On the one hand this led to economic and ethnic tensions between the Dutch and Anglo-Saxon communities, on the other hand it increased the permeability of the social classes . When Robert Fulton's paddle steamer Clermont connected New York City and Albany in August 1807 , this accelerated change in the Hudson Valley even more and shook the stability of the old and isolated Kinderhook. Due to the increased immigration, the Anglo-Saxon Americans in the state soon outnumbered the native Dutch Americans in number and influence. New York as a whole was experiencing enormous economic and population growth at this time and became the United States' most important export region in the 1800s.

Van Buren attended a small village school with only one classroom. He was a fast-learning student, but had to leave school at the age of 13 because his father lacked the financial means. On the one hand, this resulted in Van Buren's lifelong uncertainty regarding his education, and on the other hand it may have been the reason for his later good relationship with Andrew Jackson, who had had a similar experience. Van Buren left home in 1796 and began an apprenticeship with the lawyer Francis Silvester. He was one of Kinderhook's most respected citizens and a staunch federalist. New Year's Eve pressured his apprentice to join the Federalists, but Jefferson saw Jefferson as more inspired by the spirit of the American Revolution than Alexander Hamilton. When Francis Silvester's father, Peter Silvester , was elected to the New York Senate in 1798 , Van Buren turned down an invitation to celebrate with the family and stayed in his room despite the New Year's attempts to persuade him. According to Ted Widmer, this is where the contempt with which Van Buren was persecuted by certain circles throughout his political career began. He was soon said to sympathize with the French Revolution , Maximilien de Robespierre and Jean Paul Marat , which against the background of the quasi-war with France was an insulting accusation. At this time the brothers John Peter and William P. Van Ness began to be interested in the young trainee lawyer, who meanwhile knew how to hide his simple status with selected clothes. The Van Ness brothers belonged to another influential family in Kinderhook and were staunch Jeffersonian Republicans . When Van Buren successfully assisted John Peter with a caucus in 1801 that earned him a nomination for the United States House of Representatives , the Van Ness family reciprocated. She financed Van Buren a trip to New York City in 1802, where he continued his legal training with William P. The bitter clashes between federalists and republicans at this time formed the early stage of a multi-party system and served Van Buren as an ideal of political competition for the rest of his life.

Through William P. Van Ness, who was one of Vice President Burr's closest confidants and a few years later his second in the fatal duel with Hamilton, Van Buren entered New York politics just as the Republicans gave the Federalists control of the State wrested. Burr also paid so much attention to him that he felt increasingly connected to him. There is no evidence to support the rumors that later emerged that he was an illegitimate son of the Vice President. However, in fact they cannot be refuted either. It is noticeable, however, that this rumor only emerged when it was politically harmful to have had a close relationship with Burr. Van Buren was admitted to the bar in November 1803 and returned to Kinderhook, where he and his half-brother James Van Alen opened a law firm that quickly became a success. Despite his great esteem for Burr, he subordinated this friendship to party discipline and supported his opponent Morgan Lewis , the regular candidate of the Democratic-Republican Party, which is now the official party organization , in the gubernatorial elections in April 1804, which were then held every three years Jeffersonian Republicans was. It then fell out with the Van Ness family, who supported Burr.

In the next few years, Van Buren developed his political commitment parallel to his legal work. With great enthusiasm he supported the Jefferson presidency wherever he could. When it came to internal party fighting again in the gubernatorial elections in New York in 1807, he stood with George Clinton and DeWitt Clinton on the side of the regular candidate Daniel D. Tompkins , who became an important political ally for him. Van Buren concluded from this renewed internal conflict that the party needed tighter discipline. On February 21, 1807, he married Hannah Hoes , with whom he grew up in Kinderhook. As the granddaughter of a maternal uncle, she was a second degree niece of Van Buren. Hannah gave birth to four sons before she died of tuberculosis on February 5, 1819 after three years of illness . Van Buren's feelings for Hannah remain a mystery, as he barely mentioned them in his surviving correspondence and autobiography. Van Buren remained unmarried afterwards.

After the wedding, the young couple moved to Hudson , where Van Buren ran his law firm from then on. He quickly became a successful business man and earned a reputation for being one of the most talented lawyers in the Hudson Valley. Van Buren often represented small land tenants who defended themselves against the questionable property titles of the large landowners from colonial prehistoric times, for example against the Livingston and Van Rensselaer families in 1811, from which he benefited in the Senate election the following year. He did not hesitate to attack the doctrine of the famous lawyer James Kent and to question the then widespread practice of guilty prisons. In this phase of his life, Van Buren developed skills such as meticulous preparation, zeal for work, shrewdness and easy-to-understand language that later distinguished him as a politician and, in connection with his small height of just under 1.68 m, the nickname Little Magician (German: " Little Magician ”). In addition, there was an excellent memory, high social competence and excellent communication skills. Van Buren's early biographers, including George Bancroft , emphasized the central role of these years in Van Buren's later career. Lawyer activity remained his main occupation until 1821, when he entered the United States Senate, and he was one of the most skilled lawyers to ever become American President, according to biographer Donald B. Cole.

Political career up to the presidency

In the New York Senate

In 1812, Van Buren ran for the New York Senate , which, like the entire state legislature, was elected every 12 months. His reputation as an advocate for the common people proved very useful in this endeavor. When the vote was counted in April, everything pointed to a victory for federalist rival Edward Livingston . Van Buren had already embarked on a paddle steamer to New York City in the first week of May in Hudson to resume his legal practice, and had just disembarked when his brother-in-law met him on a rowboat. From him he learned that he had won the election with a margin of 200 votes, which was about half a percent. He was 29 years old at the time and the second youngest senator in the state's history. He took office on July 4th, American Independence Day . At almost the same time, the fighting began in the British-American War , most of which took place in New York and drove New England to the brink of secession, while the federal government in Washington, DC was divided and acted poorly. The war of 1812 and its aftermath remained the central theme of New York politics until 1820. Van Buren, who had taken a stand against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland before the election , was part of the war faction. He saw not only the country endangered by the British attack, but also its republican and liberal basic order.

In the presidential election of 1812 , like many New York Democratic Republicans, he initially supported DeWitt Clinton against James Madison , as there were reservations about always being behind candidates from Virginia . To hide Madison's supporters that Clinton had colluded with the Federalists, Van Buren convened a caucus; a tool he used frequently throughout his political career. It was not until Clinton had won it that a vote was taken on the electors for the Electoral College , who were then elected by the State Legislature in New York. The subsequent defeat of Clinton by Madison and his advances in the direction of the federalists, who spoke for a peaceful understanding with Great Britain, damaged Van Buren's position within the party for a short time.

Clinton was the first major obstacle to Van Buren's political rise. At first they cooperated with each other, and Clinton supported Van Buren's election to the New York Senate. When Clinton returned to his authoritarian habit and Van Buren felt that he was lying by him in the run-up to the 1813 gubernatorial election, that alliance broke. In many respects they were opposing natures: Clinton, who came from a rich and powerful family and was of large stature, was a political leader with great personal charisma, a sense of theatricality and a great deal of self-confidence and even arrogance, which is why he was also Magnus Apollo was called. Coming from a modest background, the sociable Van Buren, on the other hand, lived mainly from his organizational skills and put the party first, not his personal whims. The specific reason for the open rift between the two came when Clinton asked Van Buren to nominate him for the office of lieutenant governor . Van Buren formally complied with this request, but made it clear in the sarcastic address that he actually considered John Tayler to be the better candidate. Through this emancipation from Clinton and rapprochement with the Tompkins camp, he was able to establish himself as the leading politician in the New York Senate. All this strengthened Van Buren's conviction that systematic party competition should take the place of internal factional struggles. In an address for the 1813 gubernatorial election, he expressed himself in this spirit and adopted more nationalistic tones than could be heard in Jefferson's republicanism, and gave a foretaste of the later Jacksonian Democracy .

At the beginning of 1814 Van Buren was heavily involved in war legislation and in the elections for the state legislature, in which the federalists suffered a clear defeat in April. In the same year he served as a legal officer in the court martial against General William Hull , who had to answer for the task of Detroit . Two weeks after the British advance in New York was halted by the Battle of Plattsburgh , the State Legislature met for an emergency session in late September 1814 to decide on measures of war. The heart of these resolutions was the Van Buren Classification Bill , which was passed on October 24th . This law laid the temporary two-year conscription firmly of 12,000 recruits in the state, but did not appear in force since the war ended before. The politician Thomas Hart Benton later rated it as the most forceful law of war in American history. Secretary of War James Monroe used the Classification Bill in December 1814 as a template for a similar act at the federal level. At the end of the war, Van Buren was one of the leading Republicans of New York, also because he took up popular issues by positioning himself against guilty prisons and a re-establishment of the First Bank of the United States .

Van Buren felt at the time that the state needed political change. Since he was not alone with this perception, he formed a network of like-minded people, which was mainly held together by the aversion to Clinton. For this company, the historical context proved to be helpful: The economic growth of New York in the first decades of the 19th century, probably unmatched in American history, and the associated change, had meant that power and influence no longer existed in a few large landowning families were in the Hudson Valley, but concentrated in Manhattan on capital and trade. Gone were the days of aristocratic families who controlled the fortunes of the state through personal relationships. Van Buren's network also included young journalists and lawyers, including men like Benjamin Franklin Butler , John W. Edmonds , William L. Marcy, and Silas Wright , who later formed the inner circle of the New York Democrats.

The first goal of the early ropes around Van Buren was to wrest control of the Democratic-Republicans of New York from Ambrose Spencer . A first success was in this respect the choice of Van Buren for Attorney General of New York in 1815. In the nomination for the presidential candidate of the Democratic-Republicans for the elections in 1816 he was not sure whether he or Monroe, Tompkins William H. Crawford should support . Van Buren favored Tompkins, but he felt that the time was not yet ripe for the replacement of the so-called Virginia dynasty, which included Presidents Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. He therefore focused on his re-election as Attorney General, which he succeeded in April 1816 despite Spencer's opposition. The following year, Van Buren suffered defeat when his greatest political opponent, Clinton, was elected governor of New York with the support of Spencer. After the political defeat by Clinton in 1817, Van Buren had personally experienced three difficult years, which were marked by bereavement in close family circles. After his father died in 1817 and his mother died in February 1818, Hannah succumbed to a serious illness in February 1819, which plunged him into a psychological crisis. Clinton recognized Van Buren's weakness and took the opportunity to dismiss him as Attorney General that July.

In Van Buren, the realization gradually matured that he could not gain control of the Democratic-Republicans with his rope team, which is why he founded his own political organization in the spring of 1817, which until 1821 was the most sophisticated group of its kind in history New York and became the foundation of the Jacksonian Democracy . Its members were known as Bucktails (German: "Bockschwänze") because they wore the tails of deer on their hats like members of the Tammany Hall political interest group . Influential Bucktails included Senator Nathan Sanford , Samuel Young of the Erie Canal Commission , Erastus Root of the New York State Assembly , Walter Bowne , Lucas Elmendorf, and Peter R. Livingston of the New York Senate, and most importantly Vice President Tompkins. They developed a clear party program, great solidarity, and brilliantly used the press as the heart of the organization. The newspaper Albany Argus , whose founding Van Buren had financially supported in 1813 and whose main investor he was from 1820, played an important role . The ideological foundations of the Bucktails were the principles of Jefferson , but they adapted them to the economic dynamism of New York. Like their role model, they advocated the interests of the peasants in particular and defended them against exploitation by speculators and banks, but had the rapidly growing population of New York City as a further power base . Although they, like Jefferson, generally rejected high levels of government investment, they supported the construction of the Erie Canal in the face of public pressure from spring 1817 . Despite the understanding on the matter, Bucktails and Clintonians remained two opposing camps within the Democratic-Republican Party, diametrically opposed to each other.

Bucktails' strength was first revealed at a Democratic Republican caucus in January 1819, when their candidate for Speaker of the New York State Assembly was victorious. In the same year they were able to place a member on a vacant position in the Erie Canal Commission and began to hold their own caucuse. They wrestled with the Clintonians to win over the dwindling number of federalists in the state legislature. To this end, they supported the election of the federalist Rufus King to the United States Senate in December 1819 . Another problem for Van Buren was the debate about Missouri's accession to the United States, which was closely linked to the slavery issue . In New York, with the support of the Clintonians and Federalists, the abolitionists grew stronger , while in the Senate King, now an ally of Van Buren, spoke out against the expansion of slavery. Since Van Buren feared a rapprochement between Kings and Clinton and, on the other hand, could not dare to take sides for slavery in view of the mood, he acted cautiously. Although he signed a petition by the Clintonians initiating a meeting on the subject in Albany, he stayed away in the end. As a result, his opponents in the southern states later accused him of being an abolitionist, while in the northern states he was accused of the opposite. With the help of their press organs, the Bucktails gained considerable strength in 1820, although their success in the April elections was not as great as Van Buren had hoped, as Clinton was re-elected governor. Van Buren himself had not run for the New York Senate again; one of the reasons was uncertainty about his chances of winning. The majority in the Council of Appointments , a government body responsible for assigning posts in the public service, proved to be important . This allowed Van Buren to serve as patronage and to exchange hundreds of federalists and Clintonians for bucktails , including Samuel A. Talcott as Attorney General and his brother-in-law as Head of the State Printing House of New York. In the spring of 1821 Van Buren stood against the Bucktail Sanford, who was supported by Clinton, for a Senate seat in the 17th Congress of the United States . In the end, the party discipline of the Bucktails proved to be superior to Clinton's leadership concept, which was based on a merger of parties, as they almost unanimously voted for Van Buren, although several Bucktails preferred Sanford. With this, the Bucktails had finally established themselves as a political power and turned the complex network of competing Republican and Federalist factions into a two-party system in which Clintonians and Bucktails faced each other.

In New York, in the 1821 elections , the Bucktails pushed through the convening of a constituent assembly to renew the New York Constitution of 1777. They saw this as an opportunity to constitutionally strengthen the role of the parties and weaken that of the governor. The convention, in which the Bucktails had a three-quarters majority, met from August 28, 1821 in Albany. Van Buren behaved moderately at the meeting and mediated between the radical and conservative wing. Both sides agreed on the abolition of the Council of Revisons , a government body that controlled the legislation of the State Legislature. The governor's term of office has been reduced by one year to two years. The right to vote was expanded so that the number of eligible voters in the state increased significantly to 260,000. The right to vote for free African Americans was highly controversial. Although Van Buren opposed the forces who wanted to completely deny blacks, he and others set the required fortune at US $ 250 , which denied many of them the right to vote. When it came to filling positions, Van Buren prevailed on almost all of his proposals, with the exception of the appointment of justices of the peace , which called for the dissolution of the Council of Appointments and the allocation of offices, depending on the position, by the Senate, governor or in most cases local elections, which strengthened party control. He was also successful in judicial reform, which included a replacement of the New York Supreme Court , the supreme court of the state, which he got rid of opponents such as Spencer and William W. Van Ness . In addition, Van Buren, who dominated the assembly, was able to establish a new layout of the Senate districts in the constitution, which favored the bucktails in future elections. The Constituent Assembly of 1821 was an important step in Van Buren's transformation process from a politician of regional to one of national importance. In the months after the convention, the Bucktails gained more and more political control over New York as a party machine based on the new constitution through patronage of offices and clientelism , so that they soon became known as the Albany Regency (German: "Albany Regency"), at their head Van Buren was enthroned. Although the Albany Regency was built on the spoils system , its leadership was not corrupt, as it made posts for political and non-personal reasons. The Regency and Van Buren soon became synonymous with a new political concept that overcame the founding fathers' consensus orientation with their contempt for parties and understood them as democratic organizations that enabled more political participation and the handling of fundamental, inevitable conflicts. When Clinton announced in the summer of 1822 that he would no longer run for governor, Van Buren had finally triumphed over his political archenemy.

In the United States Senate

After the Constituent Assembly, Van Buren went to Washington to take his seat in the 18th United States Congress . Since by then he had found foster parents for all of his sons, he could now concentrate fully on politics. His first appearance at the United States Capitol began disastrously when he completely lost the thread in his speech, fell silent and sat down again in public humiliation. After he had calmed down, he continued speaking and won the debate. Despite this difficult start, he quickly became a senior figure in the Senate and, among other things, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee . Van Buren also succeeded in eliminating the Clintonian John W. Taylor as Speaker of the House of Representatives and replacing him with Philip Pendleton Barbour . In particular, he developed a close political relationship with the Old Republicans (German: "Old Republicans") around Nathaniel Macon , John Taylor of Caroline and John Randolph of Roanoke . This faction adhered to the classic republican ideals of Jefferson and, like the radicals of the north, including Van Buren and James Buchanan , rejected the nationalism of Monroe. Their positions on the customs issue and with regard to subsidies for transport projects did not always coincide, but overall, the political proximity to the Old Republicans pointed the way for Van Buren's further career. Van Buren's goal was to revive the Democratic Republicans within a multi-party system. To this end, he strove to found a new national party organization of unprecedented strength and reach, the foundation of which was, on the one hand, an alliance between his home state and Virginia and, on the other, an attractive program that met the interests of as many regions and social groups as possible. At first, the progress on this project was slow. Van Buren got into a conflict over office patronage with President Monroe early on, which further increased suspicion in the president. For him, Monroe, surrounded by many federalists, was only on the surface a Republican. At that time it became evident that George Washington's ideal of a state without party competition in a country that was no longer a simple agrarian society but expanded westward and, as New York in particular was increasingly shaped by urbanization , industrialization and financial capital , could not work.

Van Buren was on friendly terms with the women of Washington in many ways without having affairs. In particular, his association with Jefferson's granddaughter Ellen Randolph sparked gossip in town. From this time on, Van Buren developed close relationships with an unusually large number of politicians from the southern states, including influential people like John C. Calhoun and Randolph from the start. He made meaningful future friendships with younger southerners with Louis McLane and William Cabell Rives . He recognized the political potential of travel earlier than others and regularly visited the south for long periods of time. One of his connections here he built up with the journalist Thomas Ritchie , the leading head of the Richmond Junto (German: "Richmond-Clique"), which, as Virginia's party machine, was the counterpart to the Albany Regency . In May 1824 he visited Jefferson in Monticello for several days . The encounter with his idol breathed new life into Van Buren's republican ideals and reinforced his fundamental aversion to President Monroe. Also in the run-up to the presidential election of 1824 , Van Buren began correspondence with ex-President Madison and visited another with John Adams in Quincy .

The Monroe presidency, which was the hallmark of the Era of Good Feelings, aimed at unifying political opposites and merging parties , had intensified rivalries between people and factions through its passivity. So it came about that the presidential election in 1824, with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams , Secretary of the Treasury Crawford, Secretary of War Calhoun, Henry Clay and Jackson recorded an exceptionally large field of participants. After careful consideration, Van Buren supported Crawford from the spring of 1823, who was closest to the positions of the Old Republicans and, according to Van Buren, could most likely unite the northern and southern states behind him. In February 1824, Van Buren convened a caucus of Democratic-Republican Congressmen; this has been the means of nominating a presidential candidate since 1796. At that time, however, this form of nomination was already considered anachronistic and insufficiently democratic, which is why, apart from Crawford, none of the other candidates and only a few members of Congress were present. This rump assembly of 66 congressmen elected Crawford as presidential candidate and Albert Gallatin as his running mate . More important than this election is the fact that this gathering signaled the rise of a new powerful coalition of northern and southern politicians, a proto-party led by Van Buren and Ritchie, and which formed the basis for Jackson's victory in 1828 . A short time later, Adams tried to get Van Buren out of the way as a political opponent in New York by unsuccessfully proposing President Monroe for an appeal to the Supreme Court .

A stroke in the late summer of 1823 left Crawford largely silent, deaf, and immobile; This meant a major setback for the election campaign, even if it later recovered somewhat. The fact that Van Buren, as the person mainly responsible, did not abandon the election campaign was later accused of misconduct. Van Buren was struggling in New York. In order to secure the important electoral votes from New York in the Electoral College, Van Buren prevented the introduction of a popular vote , which was promoted by opponents of the Albany Regency , so that the electorate would continue to be determined by the state legislature. Clinton's dismissal from the Erie Canal Commission by a bucktail proved to be a hindrance to the campaign . This humiliation aroused so much public pity that Clinton was re-elected governor. In the November 1824 vote on electoral electors in the State Legislature, Van Buren was eventually politically out-maneuvered when Clay and Adams' camps agreed on a common list, leaving Crawford in New York with only four electors. Later there was a stalemate in the Electoral College and the House of Representatives elected Adams as President in February 1825, the decisive factor being that Stephen Van Rensselaer III. Despite a different promise to Van Buren, he finally voted for Adams. For Van Buren, it was a threefold defeat: he had bet on the wrong man, held on to him for too long and could not prevent the election of Adams, who stood for the quasi-federalism of the Monroe government. This event also damaged Van Buren's party organization and the Albany Regency .

One of Van Buren's main concerns was to turn the rapidly increasing economic and demographic weight of New York into more political influence within the American Union. To this end, and to strengthen the weakened party base in New York, he came to an understanding with Clinton after the presidential election was lost. Through this alliance, Van Buren was able to unite his proto-party behind Jackson for the upcoming presidential election , seeing as the strongest alternative to Adams, and secure his re-election in the 20th Congress in February 1827. As a lesson from the defeat of 1824, he drew the knowledge that the integration of diverging interests into one platform was necessary for a victory. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 served as this common basis , in the creation and establishment of which almost all of the important political leaders of the following decades were involved. The awkward and unpopular Adams presidency, which lifted several former federalists into important positions, played into Van Buren's hands in renewing republicanism in the classic Jeffersonian sense and developing this movement into a full-fledged opposition party . Van Buren's summer retreat in Saratoga Springs in 1826 played an important role , where he began to bring together the opposing factions of Calhoun, Crawford and Jackson. The first joint effort of these forces in the 19th Congress turned out to be the isolationist opposition, in the tradition of Washington, Jefferson and Monroe, to the participation of the United States in the Panama Congress of July 1826. About Christmas 1826 Van Buren went to South Carolina and won there from Calhoun, who was Vice-President in the Cabinet John Quincy Adams , the support for Jackson as a presidential candidate. Calhoun later became Vice President under Jackson, serving in this capacity under two competing presidents, an event that is unique in American political history to this day. On another trip to the southern states, Van Buren won Crawford for the Jackson camp. Van Buren also allied himself with other political leaders from other states, such as Buchanan in Pennsylvania , Amos Kendall and Francis Preston Blair in Kentucky , Isaac Hill in New Hampshire , Benton in Missouri and John Henry Eaton and Sam Houston from the Nashville Junto , of the Tennessee party machine. In the fall of 1827, Van Buren focused on the New York State Assembly elections, where he fought the nascent Anti-Masonic Party , and was able to achieve a clear victory for the Jacksonians . At this time he cemented the relationship with Jackson, who for a long time was undecided whether he should stick with Van Buren or Clinton as an ally in New York. After Clinton's death in February 1828, this question was settled in Van Buren's favor and the political friendship with Jackson deepened.

Van Buren hid most of these operations from the public, and he almost always managed to cover them up. A letter to Ritchie dated January 1827 gives an insight into the activities of this time. In it he expressed the hope that his new organization, which he called Democracy , would substantially change the political landscape. The aim is to systematize the disorder of candidate selection for the presidency in such a way that it is determined less by the personalities concerned and more by political content. With the emergence of a national party uniting “the planters of the south and simple republicans of the north”, the tensions between northern and southern states related to the slavery question, in particular the abolitionist attacks on the institution of slavery as such, could be absorbed. This letter was later frequently cited by historians as evidence that Van Buren was a supporter of slavery. According to historian Sean Wilentz , however, Van Buren was not concerned with protecting slavery, but rather with keeping this topic out of the election in order to strengthen the moderate forces in the North and South gathered in the Democracy . Without explicitly articulating it, Van Buren assumed that in this alliance Ritchie's Virginia would be the junior partner of New York. However, the structure of this nationwide party machine could not be hidden for long. The political opponents soon worked their way to the conceptual definition of this new political unit, where the tones were shrill and Van Buren was accused, among other things, of creating a centralist junta that formed the head of a cabalistic organization. All this did not escape President Adams and he believed he could see strong parallels between the intrigues of Burr in the run-up to the presidential election in 1800 and Van Buren's current actions.

Presidential elections 1828

Jackson and Van Buren, who knew each other from the Bundessenat, met with mutual suspicion at the beginning of their political alliance. On the one hand, Van Buren was preceded by the reputation of the shrewd and shrewd Little Magicians , on the other hand, Jackson's principled loyalty to the republican ideals of Jefferson was not always reliable. On the other hand, there were some biographical similarities such as simple origins and an early fascination with Burr. The political intersection consisted primarily in the opposition to the Adams Clay faction, from which the National Republican Party emerged until 1828 , and skepticism towards the privileged upper class. A major hurdle in Congress, in which the Jacksonians had been in the majority since the 1827 elections, was resolving the customs issue. The aim here was to bring together the diverging and sometimes conflicting interests of the manufacturing industry, agriculture and trade, as well as the northern and southern states. With Wright's support, Van Buren was able to reach a compromise here, primarily taking into account the interests of sheep farmers and other farmers in the North and Northwest , and secondly those of long-distance traders in New York, which increased Jackson's popularity in these regions. The processing companies in New England and the northern mid-Atlantic states, however, complained about a lack of protection from the "tariff of abominations". Despite this criticism, the passing of the customs laws highlighted Van Buren's abilities as a politician and gave an indication of the future strength of the Jacksonian Democrats both as a party of the president and as a power in Congress.

Unlike the previous presidential election, Van Buren concentrated on winning the electoral vote in New York in 1828. In order to achieve this, and under pressure from the Albany Regency , he ran for gubernatorial elections, benefiting from the fact that the Anti-Masonic Party and the National Republicans could not bring themselves to an alliance. Van Buren ended up beating Smith Thompson and Solomon Southwick , while Jackson achieved a landslide victory in the presidential election, winning the majority of New York's electorate. In his inauguration speech in January 1829, Van Buren addressed modern problems that plagued more and more New Yorkers, namely juvenile delinquency, electoral reform, and banking regulation . He only stayed in that office briefly as President Jackson appointed Van Buren to his cabinet as Secretary of State . Heading the State Department was the most prestigious ministerial post, which in the past had led to later presidencies more often. Van Buren had little experience of foreign policy and only drew attention to himself in this regard because he had spoken shrilly against Adams and Clay and in favor of a fairly simply structured isolationism. Van Buren's greatest competitor in the cabinet was Vice President Calhoun.

Foreign minister

Van Buren only reached Washington a few weeks after Jackson's inauguration as American President in March 1829. In the capital, he was immediately harassed at every turn by applicants who urged him for public employment within the spoils system . The sick President Jackson, who was still grieving for his late wife, Rachel Jackson , received Van Buren warmly at the White House a few hours after his arrival on March 22nd . It was their first meeting since they formed their alliance, and it was the beginning of a close personal relationship in which the similarities predominated, although they were often confronted in public as a shrewd professional politician and a strong-willed war hero. Jackson took on the role of mentor and Van Buren that of protégé . With his negotiating skills and pronounced strategic understanding, Van Buren managed to steer the hard-to-control temperament of the politically inexperienced Jackson into productive political channels. For the administration, which he found disorganized on his arrival, the Albany Regency offered a scheme of action that provided for sophisticated office patronage, close relations with Congress and its own press organs. The first setback for Van Buren came when he was unable to prevent serious mistakes as part of the spoils system . One case concerned the lucrative key position of customs collector in New York Harbor , which, contrary to his advice , was filled by the gullible Jackson with the seedy soil speculator Samuel Swartwout , who later embezzled more than one million US dollars in public funds in this office. By appointing allies McLane and Rives as ambassadors in London and Paris, Van Buren was able to strengthen his political reputation again. He competed with the Calhoun camp and a faction of western politicians including Andrew Jackson Donelson , Eaton and Kendall for power and influence over the president. Gradually a so-called kitchen cabinet of close advisors, including Van Buren, developed around Jackson . The confrontational behavior of Vice President Calhoun, who developed from a nationalist to an ardent representative of the southern states, proved to be a serious problem during the first term of office. He responded to the "Customs Tariff of Abominations" of 1828 with the protest note Exposition and Protest , which formed the basis of the nullification doctrine. According to this, individual states would have the right within the framework of American federalism to refuse to implement federal laws that they do not like.

This mixture of Jackson's temperament, the rivalry between Calhoun and Van Buren as well as a gossip-addicted capital with all its negative side effects formed the basis for the petticoat affair , which had enormous political consequences. This affair was triggered by the wife of Eaton Secretary of War, Margaret "Peggy" O'Neale, who had started a sexual relationship with Eaton during their first marriage. This made her a non-person in the high society of Washington. The wives of the cabinet members, most notably Floride Calhoun , and the unofficial first lady , Jackson's niece Emily Donelson , denied their respect to O'Neale, despite the president's protection. Van Buren, who was the only cabinet member to seek reconciliation, emerged politically stronger from this affair. By December 1829, Jackson therefore decided against Calhoun and for Van Buren as his successor. Van Buren's success in the State Department also played an important role in this decision. He was able to negotiate a trade agreement with the United Kingdom that opened the ports of the British West Indies to American ships in November 1830 , benefiting from his Anglophilia . In July 1831 he received compensation from France for seizures in maritime trade that went back to the time of the coalition wars. He also managed to negotiate an agreement with the Ottoman Empire that became the basis for the later strategic alliance between these two states. Van Buren's attempt to buy up Texas failed because of Mexico's reluctance. He also advised the President on domestic policy and created the basis for a Jackson veto that prevented federal funding for a road construction project in Kentucky. Van Buren's line was to only promote such infrastructure measures, which increased in frequency in the face of western expansion and the economic growth of America, only if they affected several states.

Domestically, Van Buren tried to mediate between Jackson’s nationalism and the Old Republicans , who strongly emphasized the rights of the states , which was put to a severe test in the first half of 1830. On April 13, 1830, shortly after an intense debate in the Senate between Robert Young Hayne and Daniel Webster over the primacy of the federal over the states, there was an open rift between Calhoun and Jackson at a reception on the occasion of Jefferson's birthday. Since this dinner was organized by the Calhoun supporter Hayne, Van Buren and Jackson had anticipated a trap and prepared themselves. When Jackson made a toast to the American Union late that evening , Calhoun was so irritated that he responded in anger with a toast to the freedom of the states. Typically, Van Buren tried to mediate with his toast without being able to cement this public rift between President and Vice President. For Calhoun, the situation worsened when the president learned that he had spoken out in favor of his arrest and conviction for the invasion of the Spanish colony of Florida as Minister of War in the Monroe cabinet in 1818 . In order to secure his own succession as president and to bring about a new cabinet without Calhoun supporters, Van Buren persuaded Jackson to accept his resignation as foreign minister. He also had the feeling that he had already achieved the best possible in this position. Jackson then appointed Van Buren as the American ambassador to London .

Ambassador to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

In mid-August 1831, Van Buren set out for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland , taking his son John with him as a personal assistant. Jackson provided him with a very generous supply, which he made full use of. He was soon on friendly terms with the British royal family . A particularly meaningful friendship developed with the writer Irving, who worked as a secretary in the embassy and introduced the Van Burens to English culture and history. On one occasion he met Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord , with a long conversation taking place between the two, as they were instantly likeable. Since the borderline of the northeastern United States, which was disputed with the United Kingdom , had been settled shortly before through the mediation of the Dutch King Wilhelm I , Van Buren had few diplomatic obligations. Van Buren developed such strong sympathy for English class society - he was more on the side of the conservative House of Lords on the question of electoral reform, for example - that a compatriot reminded him of being an American republican. In February 1832, shortly before a reception by the Queen Victoire of Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld , Van Buren learned that the Senate had rejected his appointment as ambassador with a majority of one vote, with Vice President Calhoun having given the decisive vote in the 22nd Congress , who had previously left the Democrats. This event, similar to Clinton's dismissal from the Erie Canal Commission in 1824, sparked a wave of sympathy with the battered man returning to America in martyrdom. Before Van Buren went home, he visited the Kingdom of the United Netherlands and Cologne to do genealogy.

Vice President

At the first Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in May 1832 , Van Buren was elected in absentia as Jackson's running mate for the presidential election that year . When Van Buren set foot on American soil again on July 5, he quickly found that his year-long absence had fallen into a politically favorable period. During this time, debates in Congress over the expiration of the Second Bank of the United States ' charter , known as the "banking war," and new customs legislation had deeply divided the Democratic camp right down to the cabinet. A deeper rift opened up, particularly between the northern and southern states. Just days after his arrival, Jackson vetoed the end of the Second Bank of the United States. As a New Yorker, Van Buren was far more benevolent of the concept of a central bank than the representatives of the western states that surrounded Jackson. Nevertheless, Van Buren looked powerless towards the end of the Second Bank of the United States and remained passive on the question that followed, namely the outsourcing of federal funds from the central bank and storage in other banks. The nullification crisis came to a head in 1832 that Calhoun threatened the secession of South Carolina and Jackson in return in January 1833 with federal troops and the declaration of a state of emergency , with Van Buren personally rejecting this so-called Force Bill (German: "Armed Forces Law"). Ultimately, the conflict was defused for both sides while saving face, but it poisoned the climate between the northern and southern states until the 1860s. Van Buren and his political camp were able to claim that they were taking a moderate position between the two extremes in all these conflicts. These conflicts sharpened the ideological profile of the Jacksonian Democracy , which formed three interwoven guidelines: a robust, constitutional nationalism curbed by restraint in the federal government's spending policy , a deep-seated distrust of the power of concentrated capital, and absolute prioritization the democratic will of the people.

At this time there were the first initiatives to form a new party whose primary goal was to preserve the American Union and to fight against the fact that the economically backward South had so much power in Congress. Van Buren saw this development with concern and suppressed it with all his might, fearing for his chances to succeed Jackson and seeing the power of the Democrats as a national party endangered. As an alliance held together almost exclusively by an aversion to Jackson and Van Buren, a party was formed from a different direction. This movement, based on the British Whigs and their fight against King George III. , with whom President Jackson was identified, soon to become known as the United States Whig Party , was a surprising alliance of quasi-federalists from the northern states and politicians from the southern states who overrode state rights over federal. Prominent members of the Whigs included Clay, Webster and, for a time, Calhoun. Despite everything, Jackson and Van Buren won the 1832 presidential election against Clay and John Sergeant of the National Republican Party . In the summer of 1833 he toured New York and New England with Jackson, thereby strengthening the solidarity of the Democrats.

Presidential elections 1836

The succession debate usually begins two years before the election; so it was in this case too. In 1834 discussions began about the extent to which Van Buren was a worthy and capable successor to Jackson. Since he had outmaneuvered a number of politicians during his career, including many who were of better origin and therefore took their defeat like Calhoun personally, he found himself exposed to hatred in places. In addition, Jackson's presidency had caused irritation in many places, for example due to the customs tariffs and the end of the Second Bank of the United States, for which Van Buren was held jointly responsible. In the southern states, he was accused of sympathizing with the abolitionists, with his attitude during the Missouri Compromise and friendship with anti-slavery Rufus King as evidence. Many in the region also held his personal feud with Calhoun against him. In the northern states, however, Van Buren was often rejected because he was seen as an advocate of slavery. Many also bothered that Van Buren was a professional politician. He was taken up as a subject by a number of humorists, with his small body size and stronger stature often being discussed. The politician Davy Crockett caricatured Van Buren as a feminine and androgynous being and gave him the nickname Aunt Matty (German: "Aunt Matty"). The story The Partisan Leader by Nathaniel Beverley Tucker , published in 1836 with the support of Calhoun, went in the same direction .

The greatest advantage of Van Buren for the presidential election turned out to be the support of Jackson, who specifically built him up as his successor. To do this, he used the party leaders devoted to him as well as the democratically controlled press. This was decisive in ensuring that internal party disputes ended and Van Buren was elected as a presidential candidate by a clear majority at the second Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in May 1835. His running mate was Richard Johnson's mentor , who had distinguished himself militarily in the British-American War. As was customary at the time and expected by the candidates, Van Buren remained passive during the election campaign. He benefited greatly from the fact that the regionally divided Whigs put up three different candidates with William Henry Harrison , Daniel Webster and Hugh Lawson White . In the end Van Buren won with a popular vote of 50.8% and 170 out of 124 electors in the Electoral College. He became the youngest president in American history to date. Before he took office, some analysts recognized the first signs of a coming crisis.

Presidency

The inauguration on March 4, 1837 had more than 20,000 spectators. In his farewell speech, Jackson warned against speculation and the increasing power of capital. In his inaugural address, Van Burens emphasized that he was a young age for a president. A central theme was the American Constitution, which had celebrated its 50th anniversary the year before. Van Buren gave a comprehensive outline of their history and stated that their democratic spirit would flourish as long as there was a willingness to compromise among each other. Furthermore, he directed the audience's attention to the innovations in transport, business and party competition. Finally, he touched on slavery and promised never to interfere as President. Overall, his general inaugural address was strikingly similar to Jackson's farewell address. In order to maintain the continuity of the politics of his predecessor, Van Buren took over most of the officials from the Jackson administration. When filling positions, he showed a preference for applicants from the southern states. Since Van Buren was widowed, the role of First Lady initially remained vacant and was taken over by the daughter-in-law Angelica Van Buren after the marriage of his eldest son in November 1838 .

Van Buren's inauguration meant a generation change; he was the first American president to be born a natural born citizen . Since he was significantly younger and more sociable than Jackson, he brought a breath of fresh air to the capital's social life, to which his four sons, who were unmarried at the time, also contributed. Of these, John in particular found general approval and began to draw attention to himself as a politician. Large societies took place in the White House, which, as in the case of the “open house” event in spring 1838, had up to 5,000 guests. The lavish dinners he hosted also attracted attention. Van Buren broke with a tradition of his predecessors and accepted invitations to receptions from cabinet members and even prominent opposition politicians. Immediately after taking office, he had the aging interior of the White House renewed. Van Buren was a keen reader and invited many young writers to the White House whom he encouraged to publish articles in the United States Magazine and Democratic Review . He made several of them government posts, including George Bancroft and James Kirke Paulding . Since the heated ongoing conflict between Whigs and Democrats led to an ever-widespread interest in political news, which had not least promoted Van Buren, there were also more publication platforms for talented authors than in the past. He also showed an interest in the natural sciences. So he stood up personally for the researcher Charles Wilkes and enabled him to carry out the United States Exploring Expedition . The extensive mapping data from this expedition was very important and was later used in the Pacific War .

Economic crisis of 1837

After the year had got off to a promising start for the newly elected president, shortly after his inauguration, the economic crisis of 1837 erupted , which was the worst in the United States until the Great Depression in 1929. There had already been riots in New York City in February when the crowd protested against high flour prices. From mid-March 1837 it became clear to the public that this was a serious crisis of national importance. The crisis quickly infected cities like Philadelphia , Baltimore and New Orleans besides New York City and spared no other business center in the United States. It spread across the Atlantic to Europe, which had invested heavily in the booming American economy. The major banks in New York City had to close in early May. On May 15, Van Buren finally convened the 25th United States Congress for September for an extraordinary session.

The question of the causes of the economic crisis of 1837 is still discussed today. By that year America had seen extreme growth , accompanied by speculative fever not limited to Wall Street but nationwide. Some tycoons such as Johann Jakob Astor had become extremely prosperous, particularly in the real estate business , which benefited from the western expansion of the United States. In addition, there were new types of business enterprises such as the flourishing newspaper industry, which fueled the population's greed for sensations and turned information into a competitive advantage. Probably the best symbol of the triumphal march of the railroad in America was the turbulent economic mood of the time. The construction of the track here has not kept up with the exorbitant demand for a long time. Most of these successful companies were based in the industrialized north, such as the steel and iron industries and shipbuilding. Although prosperity reached the population and everyone was optimistic, the disturbing feeling arose that with the simple republican past, something precious was being lost. By 1830, there had been a general change in mentality, according to which competition and the pretentious pursuit of popularity were no longer frowned upon, but predominantly rewarded. This was accompanied by a commercialization and individualization of society, which was prominently described by Alexis de Tocqueville in his work On Democracy in America 1835. The era of the United States as a rural agricultural republic had thus come to an irrevocable end.

This shift in attitudes met resistance from the Democrats, who were still indebted to classic Jeffersonian ideals. In the west in particular, people viewed with great disgust the land speculations launched by the ever increasing number of banks that settled these areas. These deals were often conducted through dubious banks and middlemen. Jackson, who felt obliged to the interests of the West and was averse to banks, responded to this in 1836 with the Specie Circular (German: "Hartgeld-Rundschritten"). This directive stipulated that land purchases could only be made with gold or silver coins . Aside from the fact that many Democrats were more bank-friendly, Jackson's other measures, notably the transfer of federal budget surpluses to the states, had fueled speculative excitement. The opposite effect occurred after the Specie Circular , as the banks, now fearful of a shortage of money in circulation , recalled their loans, which contributed to the panic. There was also an unfavorable trade deficit with Great Britain . When economic difficulties arose in England and Ireland , creditors called for their loans from overseas. Since cotton prices fell at the same time and the United States suffered from crop failures as a whole, this brought American banks into payment difficulties.

The immediate effects of the Depression were a wave of bankruptcies, a massive loss of liquidity and mass unemployment . Whole layers of society were impoverished and even starving. Before long the economic crisis turned into a political disaster for the President, whom the Whigs held responsible for the Depression. Van Buren, who as a follower of Jefferson's political career had endeavored to limit the power of the federal government, had now reached the limits of these classic republican ideals. All summer he sought advice from leading Democrats, but a deep rift ran through the party. The western camp around Jackson dogmatically insisted on a monetary policy and a strict separation of state and financial capital . Other Democrats, especially from the crucial states of New York and Virginia, spoke out in favor of issuing paper money and supporting the federal state banks . At the extraordinary session of the Congress on September 5, 1837, the first that was not for a military reason, Van Buren gave a much noticed speech that was distinguished by its clarity and precision. With his proposals he tried to satisfy both camps within the Democrats. For hard currency supporters, he envisaged laws that suspended the transfer of federal budget surpluses to state banks and the storage of federal funds in a bank-independent treasury . Van Buren offered the bank-friendly Democrats measures that included postponing federal lawsuits against defaulting payers and issuing banknotes . All but one of these bills were subsequently passed in Congress. The most important law, however, the establishment of an independent treasury, was rejected in the House of Representatives after a narrow victory in the Senate. The economic crisis weakened Van Buren as president in further respects by uniting the Whigs, which had been fragmented until then, in the fight against the alleged perpetrators of the depression, the Democrats. On the other hand, it destroyed the solidarity among the Democrats as a national party. Furthermore, this crisis revealed that Van Buren was not a charismatic and inspiring leader like Jackson who could rally party and nation behind him.

Even in his home state New York Van Buren got on the defensive. During the 1830s, a radical wing within the Democrats, the so-called Locofocos (German: "matches"), had formed here. They came to this name when their opponents had switched off the light at a meeting and they had used matches as light sources. The Locofocos , based in the big cities, despised the privileged upper class, were supporters of Jackson's monetary policy and welcomed the end of the Second Bank of the United States . Their overall goal was an egalitarian society . When Van Buren took up some of their points in his September 1837 proposals, particularly regarding banking, the Albany Regency responded with concern. As expected, in the face of the economic crisis, voters punished the divided Democrats in the elections in New York in the fall of 1837 and gave the Whigs a clear victory. By the spring of 1839 an economic recovery occurred and the price level almost reached the pre-crisis level, but this did not detract from the hostile mood towards Van Buren. In the autumn of 1839 a second, somewhat weaker phase of depression followed, which sent the market down again and underscored the powerlessness of the president over these mechanisms. In 1840 it was finally possible to get the law to create an independent treasury through Congress, but it was not the big breakthrough the president had hoped for. Overall, Van Buren's presidency was left badly damaged by the economic crisis of 1837, while the nation suffered not only a financial but also a psychological shock, which severely shook the self-confidence that had prevailed until then. The gloomy mood triggered by the Depression can only be compared in American history with the Great Depression a little over 100 years later and can be guessed at in the works of Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe .

The economic crisis of 1837 had positive aspects for Van Buren and the whole nation. It revealed that while Van Buren had reshaped the dynamic political landscape after the Era of Good Feelings , almost every other aspect of American society was also undergoing major changes and needed an adapted organization. In addition, it was now becoming clear to everyone outside and inside America that the United States was no longer a sleepy agrarian state , but an influential economic power whose crises had repercussions worldwide. Van Buren's skillful use of the press was also shown to be way ahead of its time: in preparation for his presidency, he had already financially supported journalist John L. O'Sullivan in founding the ambitious United States Magazine and Democratic Review in 1837 . The monthly periodical quickly became the liveliest of its kind in America. In addition to political comments from the Democratic perspective, it contained texts by well-known writers; Sun published Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman stories. During the Depression, the United States Magazine and Democratic Review did an important part in defending Van Buren, who was under attack. Some of the president’s economic countermeasures, such as the independence of the treasury or improvements in working conditions, were the result of the egalitarian Locofocos . Van Buren issued a presidential decree on March 31, 1840, which stipulated a ten-hour day for federal employees. Van Buren was thus the first president to take urban poverty into account in his program, but in keeping with the spirit of the times, he eschewed state welfare. The eminent American historian Frederick Jackson Turner therefore saw in Van Buren a forerunner of political progressivism at the turn of the century.

Slave question

Partly because of the increased international attention that America experienced during the economic crisis of 1837, the slave question came back into the focus of the public and into the political debate. Sensitive to their external appearance, many citizens in the United States were uncomfortable with reports from foreign correspondents on the subject. They often expressed amazement at a two-faced nation shared by the Mason-Dixon Lineage. While the north is characterized by advanced technology, industrialization and entrepreneurship, the south is characterized by a feudal and racist planter aristocracy, whose economy is essentially based on slavery. The fact that slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833 and even in relatively backward Mexico in 1829 led to further pressure on this question . Increasingly broader populations in America perceived slavery as a repulsive evil. As a result of all this, the previous political consensus not to discuss the slave question at the federal level, let alone to regulate it by law, was gradually broken. This destabilized the party political foundation that Van Buren had laid up to his presidency. Just his election as president had brought the slave question back into the general consciousness, since he was a Yankee and his position on this question was opaque to the public. This often resulted in observers projecting their own attitudes into his person . Determining Van Buren's actual position on this issue is difficult and depends heavily on the time and context of his utterance. In his personal correspondence there are hardly any comments on this matter. Van Buren also demonstrated great skill in staying away from Congress or the state legislature when it came to crucial votes on the slave issue. His portrayal as the spineless courtier of the slave states in the well-known film Amistad , however, only superficially corresponds to the truth.

At first glance, there is much to suggest that Van Buren was not bothered by slavery in the United States, or at least was not prepared to risk his political career because of moral scruples about it. Since he began his public office in 1812, he has pursued a clever strategy in the southern states, specifically looking for allies in this region who could help him progress and who had the same opponents in New York as he did. For these reasons it was in his own best interest not to unsettle these friends by addressing the slave question. During his inauguration speech, he first publicly mentioned the slave issue, only to assure them that he had no intention of doing anything about the matter. When Van Buren's eldest son Abraham married the South Carolina-born planter's daughter Angelica Singleton in November 1838, the president also had a family connection to the slave-holding society of the south. Whatever his personal attitude toward slavery, he did everything in his power to prevent the spread of abolitionist writings. In the run-up to the presidential election of 1836, he took care of the Albany Regency for the suppression of the anti-slavery movement in their stronghold of New York. In May 1836 he supported the Gag Rule (German: "Discussion ban"), successfully brought through Congress by Henry L. Pinckney , which provided for the postponement of all abolitionist legislative proposals for an indefinite period and thus prevented any debate on the slave question. However, this law was less radical than the more extensive proposal from the Calhoun camp, which provided for a blanket rejection of all such submissions. On the other hand, there was evidence, such as his general approval of the right to vote for Afro-Americans at the New York Constituent Assembly in 1821, which spoke in favor of Van Buren's personal opposition to slavery, which is why many southerners feared that it would be secret with him was an abolitionist. Van Buren's great and until then generally valued strength as a rational mediator who was able to reconcile opposing positions was increasingly perceived as a weakness in leadership and decision-making in view of the increasingly violent polarization in the slave question.

In this conflict, the southern states were not only bothered by the increasingly influential abolitionism in the north, but also viewed with great concern the rapid population growth and increasing political weight of the northern states. Aside from these protracted historical processes, there were concrete events that made the southern states fear for slavery as an institution, most notably the Nat Turner slave revolt in 1831, which caused panic and protracted trauma across the region . The fact that the anti-slavery movement subsequently met a wide audience with its writings and was able to fall back on the most modern printing technology was taken by many southerners as a further insult. The tense relationship that was already so tense when Van Buren took office became even more acute in November 1837 when the abolitionist journalist and pastor Elijah Parish Lovejoy was murdered by slavery supporters. Van Buren found himself in a bind now that the situation required strong leadership. If he attacked slavery, half of the party would turn their backs on him; on the other hand, if he stayed too much on the side of the slave owners, he would lose his home state, which was largely abolitionist. It was at this stage that the president showed a human side when he helped writer and journalist William Leggett. Leggett, then one of the best-known journalists in New York City, was a Democrat and abolitionist who sharply attacked Van Buren for his pro-southern policies during the 1836 presidential election and thereafter. Shortly afterwards he became very seriously ill. Van Buren then got Leggett a post at the American embassy in Guatemala in the hope that the climate there could help him recover.

Even so, Van Buren remained, in a sense, a prisoner of his own creation, as the renewal of the Democrats had also increased public interest in politics. As a public person and under constant press observation, it was no longer possible for him, as earlier politicians, to hide his actual position and to tell the audience something different depending on the place and occasion. While slave markets continued to take place within sight of the Capitol in Washington, which was extremely slavery-friendly and looked repulsive and depraved to some foreign visitors, such as the travel writer James Silk Buckingham , for example , the president found it increasingly difficult to, on the one hand, discuss the To suppress the slave question within the Democrats and on the other hand not to let the party name degenerate into an empty shell. Thus, in the fall of 1837, there was a long debate about slavery in the District of Columbia. Another important factor fueling the slavery dispute was the admission of the Republic of Texas as a state into the American Union. Texas had declared its independence in 1836, thus breaking away from Mexico. In President Jackson, Texas found an ardent supporter of his desire to become part of the United States. Since the Republic of Texas was a slave state and he did not want to strain the fragile balance between northern and southern states, Van Buren put the annexation on the back burner, which angered the southern states and even caused Jackson to write irritated letters to his successor.

In the congressional debates, the slaveholder Calhoun in the Senate and the ex-president and abolitionist Adams formed the antipodes in the House of Representatives. The fact that Calhoun, as the representative of the interests of the southern states, could count on a clear democratic majority for his resolutions, which defended slavery in strong words never heard before, implies support from the White House. An indication of the explosive mood on this issue is provided by the argument between MPs Jonathan Cilley and William J. Graves , which ended in a fatal duel . The slavery issue in the Senate became explosive because of the fact that Senate President Johnson lived with one of his slaves and was probably married to her, which was an open secret in the capital. Despite the horror that this relationship sparked among the southerners and the pressure Jackson put on the president to forego Johnson, Van Buren stuck to Johnson and got him to be his running mate in the next presidential election. One event that revealed the division of the nation over the slave issue and foreshadowed future, even tougher conflicts occurred at the end of Van Buren's tenure. In 1840, a United States Navy military tribunal in North Carolina convicted an officer for whipping seafarers, even though the witnesses were not allowed to be black in that state. When Van Buren confirmed her right to testify, he triggered a wave of indignation in the southern states.

The most famous slavery event in America today during the Van Buren presidency was the slave revolt on the Amistad and its legal consequences. In 1839 the slaves on this Spanish ship revolted, took control of it and landed on Long Island . They were imprisoned in Connecticut and Van Buren quickly ordered their transfer to their Spanish owners by a Navy ship. The case ended up in the courts and resulted in the Amistad trials . In February 1841 the fate of the prisoners was tried in the Supreme Court, where ex-President Adams obtained their release. This case throws a very bad light on Van Buren, which was intensified by the famous film adaptation by Steven Spielberg . However, it should be taken into account that the president was trying to get his re-election during this period and was dependent on the support of the southern states. Overall, Van Buren's approach to the slave question showed behavior typical of politicians, in that he avoided taking a clear position. Thus, he took himself out of the game and deprived himself of active design options. Other forces were now pushing into this gap: in New York, abolitionist Whigs were gaining strength and in other places the two-party system of Democrats and Whigs broke open, with the Liberty Party emerging from the anti-slavery movement .

Indian policy

In the past, Van Buren had always treated the resettlement of the Indians with caution, as he saw it as primarily a concern of the south and it was unpopular with the voters in his home state. In principle he shared the prevailing attitude of the whites over the Indians at the time. As President, he continued Jackson’s ruthless and brutal American Indian policy to drive the Five Civilized Tribes out of United States territory to the satisfaction of the Southern States . The Indians still living in the southeastern cultural area were deported and the land that had become free was given up for settlement . The Cherokees were particularly hard hit, rounded up by the thousands and forced from Georgia to Oklahoma on the Path of Tears . At the same time, the Seminoles in Florida faced massive persecution, to which their leader Osceola fell victim in January 1838. However, Van Buren complained to Congress about the humane treatment of the Indians by the American government. In the northern states, there was a growing sense that the hypocrisy and brutality towards the Seminole in Florida and in other matters are being guided by the overpowering slave states in the background that ruled politics in Washington.

Foreign policy