Path of tears

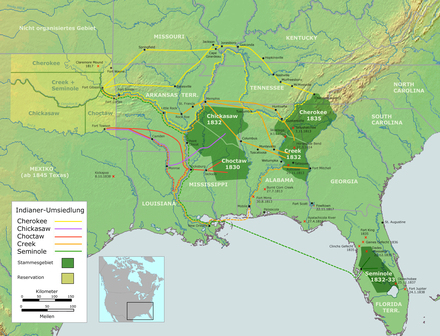

The path of tears ( English Trail of Tears , Cherokee ᎨᏥᎧᎲᏓ ᎠᏁᎬᎢ ) is the expulsion of North American natives ("Indians") from the fertile south-eastern woodlands of the USA to the rather barren Indian territory in today's state of Oklahoma . The deportations of Indian tribes mark a historic turning point and mark the low point in relations between the indigenous peoples and the government of the United States.

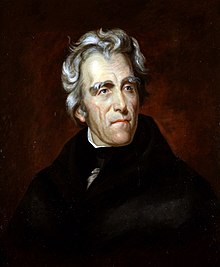

The expulsion took place against the background of the increasing demand for land by the European settlers from 1800 and the associated expansion of the North American border region. The relocation affected the Muskogee (Creek), Cherokee , Chickasaw , Choctaw and Seminole peoples, who are also described as the " Five Civilized Nations " because of their adaptation to the way of life of the colonists . In the spirit of American Indian policy , legislation covered expulsion through the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Under the treaties negotiated by President Andrew Jackson , the Indian peoples were allowed to surrender, exchange land, or sell their ancestral lands in the southern states between 1831 and 1839 or forced to evacuate through the use of the military.

The resettlement was organized in treks and followed various routes to the west, accompanied by American troops. On the way to the newly established Indian reservations , over a quarter of the displaced persons and the African-American slaves accompanying them died from illness, exhaustion, cold and hunger. The consequences for the indigenous people were devastating and lasted well into the second half of the 20th century. In addition to the serious decimation of the peoples, the tribes closely associated with their ancestral homeland were culturally and spiritually uprooted. The peoples were divided into eastern and western tribes. The allocated areas continued to be fragmented, and to conflict with other displaced tribes, and as the United States expanded westward, there was further displacement.

Despite demands from the Indian peoples who were affected by the displacement, the United States government has so far (as of June 2020) issued no statement on participation in the deportation and the associated consequences. However, two of the Cherokee Trail of Tears routes were added to the National Trails System in 1987 to commemorate the victims .

Origin of the term

The term Trail of Tears originally referred to the forcible eviction of the Cherokee and the resettlement of the Choctaw, as covered by American law. The Cherokee referred to the expulsion as Nunna daul Tsuny ( cherokee for 'The Way We Wept'), which was translated into English as the Trail of Tears and thus spread. In the case of the Choctaw, the term refers to a description of their resettlement cited in the Arkansas Gazette in November 1831 , which one of the important chiefs, presumably Thomas Harkins or Nitikechi, referred to as “ […] trail of death and tears ” (English for 'path of death and tears'). Other newspapers picked up this expression in abbreviated form as the Trail of Tears and distributed it. The term was gradually adopted for the other Indian nations of the Southeast displaced under the Indian Removal Act and is used today to describe the overall circumstances of the displacement of the Southeastern nations. Occasionally the term is used to characterize violent or loss-making expulsions or resettlement of other Indian peoples, for example for the ' Long March ' (English: The Long Walk ) of the Navajos, who lived in the southwest of the United States, in 1860 .

prehistory

Indian settlement areas in the 18th century

In the second half of the 18th century, the original settlement areas of the Indians, which originally comprised large parts of the southeastern United States, had shrunk significantly, mainly due to treaties and military conflicts with the settlers from Europe. The Indians' whereabouts in the restricted areas was initially in the interests of the colonial powers, for whom the tribal areas were also important as buffer zones between the various spheres of influence. Especially the habitat of the Cherokee and the Muskogee in the mountainous region of the states of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee separated the French , Spanish and British areas of interest from one another.

The Seminoles were already clearly decimated by the first Seminole War around 1800 in the sparsely populated central Florida and were influenced by the settlers of the Spanish Florida colony , while the Choctaw and Chickasaw in Alabama and Mississippi inhabited fertile land south of the Mason-Dixon Line separated French Louisiana from the Thirteen Colonies of British colonial power. A lack of interest from the white settlers saved the areas from further downsizing up to this point; the settlement areas of the Indians were largely treated as autonomous state areas.

Economic changes around 1800

With the invention of the egrenier machine , a ginning machine for cotton , which made the effective use of slaves on plantations and thus the cultivation of cotton possible on a large scale, the need of the white settlers for larger and larger areas of cultivation in the southeast grew. The area known as the Black Belt (English for 'Black Belt') was of particular economic interest. This is an area of black soils suitable for growing cotton that stretches from North Carolina to Louisiana. The upswing in the southern states enabled the Indian nations living in this region to increase their prosperity. The fact that the five nations had a long tradition of slavery was beneficial for economic development. Most of the slaves were prisoners of war or people of indigenous, African-American or white descent who had been robbed from other tribes. In contrast to the slavery of the white settlers, the Indian slaves were understood as part of the family association and led a largely self-determined life. However, they owed part of their labor to their owners, which had a major impact on the economic success of Indian agriculture. At the same time, the incipient hunger for land, the appearance of land speculators and the settlement of large plantations threatened the settlement areas of the southeastern Indian peoples. There were further assignment agreements and land purchases by white settlers, partly under pressure from the American government. This resulted in a further reduction in the number of tribal areas.

Acculturation

The pressure exerted on the tribes by the white settlers' hunger for land increased considerably and permanently changed their way of life and culture. With the increasing interest of the white settlers in the region, among other things, the spread of the Christian faith among the Indian nations began, which was accelerated above all by the appearance of the Moravian Brethren around 1800. In addition to proselytizing, the reduction of the tribal areas also changed the way of life of the affected peoples, for example the traditional settlement patterns of the Cherokee changed to a form similar to the European settlement method with individual management. The economic upswing in the south made it possible for the nations to establish a wealthy class of plantation owners. As the well-documented case of the Cherokee tribal leader John Ross shows, they served as role models for many of their tribal members. The nations developed a political system similar to that of the American-European government and justice system, built schools, and increasingly adapted to the way of life of their white neighbors. During this phase, the Cherokee developed their own written language and published the first newspaper in English and Cherokee.

On the one hand, this adjustment came under pressure from the American government, according to which the assimilation and acculturation of the Indians should serve as a measure to protect the indigenous population, to avoid military conflicts and, in particular, to promote trade. On the other hand, some tribal leaders hoped to become part of the social structure of the United States and thereby protect themselves from further displacement and expropriation of the tribal areas. The high degree of acculturation of the Indian peoples from the point of view of whites led to the term “five civilized nations”, which was used to describe the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muskogee and the Seminoles influenced by the Spanish mission. A recognition as equal members in the society of the white settlers hardly took place. The majority of the settlers still regarded the Indians predominantly as a race inferior to their culture and civilization. Parts of the Indian population vehemently rejected this adaptation to the foreign culture and massive internal conflicts within the tribes arose. This was most evident with the Muskogee, also known as the Creek, whose large and influential confederation split into two parts, between which there was ultimately a civil war.

Indian Removal Act

The white settlers of the southeastern states put increasing pressure on their respective governments at the beginning of the 19th century. They asked them to vacate the tribal areas and to make the land and - especially after gold discoveries in Georgia in 1829 - available to the whites.

In order to put the necessary resettlement of the Indians on a legal basis, the Senate of the United States passed the Indian Removal Act on April 24, 1830 , which the House of Representatives approved on May 26 of the same year. With the support of the southern states and against the opposition of important politicians like Theodore Frelinghuysen and Davy Crockett , Andrew Jackson signed the law on May 28, 1830. This, authorized him to negotiate with the living on German territory tribes and peoples that an exchange of their lands against areas in the Indian Territory (English Indian Territory ) should aim. These territories acquired by the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase were not part of the federal system of the United States at that time and were located in what would later become the state of Oklahoma .

The Indian nations reacted differently to the new legislation, for example the Choctaw renounced their land east of the Mississippi in September 1830 in exchange for land west of the river. The Cherokee tried to strengthen their sovereign rights and to defend themselves legally against the various land assignment treaties. In the context of the Indian policy and the Indian removal (English Indian Removal ), the complaints brought by the nation at the Supreme Court were defeated. The Seminoles, on the other hand, refused to attempt any non-violent resettlement and put up a military defense in the Second Seminole War .

Displacement and Resettlement of Peoples

Choctaw

Dancing Rabbit Creek contract

The settlement area of the Choctaw nation comprised large parts of the present-day states of Mississippi , Alabama , Arkansas and Louisiana until 1800 . Through a series of treaties, the nation was initially displaced to areas north of the Mason-Dixon Line, until it finally exchanged most of its settlement areas for new areas in Indian territory after the adoption of the Indian Removal Act with the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek . In the treaty signed on September 27, 1830 under pressure from the American government and which came into force on February 24, 1831, the Choctaw ceded around 45,000 square kilometers of land (an area comparable to the size of Switzerland ) to the federal government and received around 61,000 square kilometers in the present Oklahoma. The treaty, in which the nation renounced its sovereignty, did not have the approval of the people, who had spoken out against relocation in previous meetings and councils. However, the Native American negotiators Greenwood LeFlore , Musholatubbee and Nittucachee saw no other way of preserving at least a remnant of the original tribal areas for their people. The Indians remaining in Mississippi also became citizens of the United States, which the Choctaw leaders hoped would provide better protection for those who did not want to join the resettlement.

Relocation in the fall of 1831

The voluntary resettlement of the Choctaw, estimated at 15,000 to 20,000 members, and her approximately 1,000 African-American slaves was planned by the federal government in three groups. The first and largest group comprised 4,000 people whose resettlement on the "water way" was planned for October 1831. The tasks of the government-appointed " Removal Agents " (English for "resettlement agents " ) under the direction of George Strother Gaines consisted of planning the routes to Indian territory just 650 kilometers away and the procurement of wagons, horses and ships as well an appropriate amount of supplies and food for the treks and the first time after arrival in the new settlement area. There was disagreement among these agents about the choice of routes and the organization of the treks. The first group, Choctaw, encountered an unclear and confusing situation upon arrival at the assembly points in Vicksburg, Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee . For example, contrary to the government's assurances, they had to leave their cattle behind and were only to receive replacement for them in Indian territory. Due to the worsening weather conditions, the agents decided to transport the Choctaw from Memphis along a northern route and the tribal members gathered in Vicksburg along a southern route into Indian territory.

Memphis to Little Rock Route

The approximately 2,000 Choctaw assembled in Memphis boarded the provided steamships with which they were to follow the Arkansas River first . The heavy rains that began a few days after the departure led to floods that caused the ships to land at the Arkansas Post . There was no shelter on land for such a large number of people. Blankets and supplies had not been carried for such a case. The cold rain and subsequent blizzard , to which the Choctaw were defenseless for several days, caused a large part of the total deaths within this group. The youngest and oldest were particularly hard hit. The two ships, the “Reindeer” and the “Walter Scott”, were unable to cast off at temperatures well below freezing, which meant that it was no longer possible to transport the Choctaw by water. It wasn't until eight days later that forty government wagons loaded with blankets and supplies were dispatched to the group from Little Rock, Arkansas . They picked up the survivors at the Arkansas Post and took them to Fort Smith, from where they moved to Little Rock. After the arrival of the first wagons in November 1831, one of the tribal leaders, probably Thomas Harkins or Nitikechi, coined the term "Trail of Tears" in a conversation with a reporter for the Arkansas Gazette .

Vicksburg to Little Rock Route

The Choctaws waiting in Vicksburg to be transported also boarded two ships. The "Talma" and the "Cleopatra" were supposed to bring the group, following the Mississippi downstream to the confluence of the Red River and from there following the Ouachita River upstream, to Camden in the then Arkansas Territory . From there, the Choctaw should cover the remaining 100 kilometers to their new areas in covered wagons. However, the waterway transport had to be interrupted in Monroe, Louisiana , due to a machine failure of the "Talma". The Choctaw should wait there to be gradually transported on with the "Cleopatra". The rains and blizzard did not hit this group as hard as the displaced on the northern route because of the protective forests in the area and the supplies generously shared with the Choctaw by the white population. Shortly afterwards, the southern group reached their stopover at Camden. The preparations made by the agents there were nowhere near what was needed. There were only twelve wagons available and the food rations weren't enough. With the exception of the toddlers and the weakest, the Choctaw were forced to walk the rest of the way. The lack of food was taken advantage of by the farmers along the route. They charged three to four times the usual price for supplies. Various epidemics, including typhus and diphtheria , also delayed the trek. The stretch from Camden to the Mountain Fork River, which is just over 100 kilometers long, took just under three months.

Relocation in the fall of 1832

Although Gaines was aware that the resettlement via the southern and shorter route had gone more smoothly and with fewer losses, he decided to take the northern route again in 1832 for reasons unknown. When the Choctaw moved towards Vicksburg to be transported west together, a cholera epidemic broke out in the region . The Indians who also fell victim to this disease died by the hundreds. The city was largely deserted and there were no supplies to buy. The crews of the ships rented for the Choctaw had also fled the epidemic. Agent Francis W. Armstrong, who was supposed to lead a group of about 1,000 Choctaws to Vicksburg, heard about the epidemic. He spontaneously decided to first bring his group to Memphis in order to lead them westwards via the southern route as quickly as possible. His wards reached almost all of the Indian territory without further incident. Gaines finally managed to hire a crew for at least one of the two ships, the “Brandywine”. Around 2,000 people were brought onto the ship. Shortly after it left Vicksburg, it started to rain. It was not possible to continue on the flooded river and the passengers were put ashore about 110 kilometers from their destination Little Rock near Rock Row. There were no supplies available there, there were no wagons or horses. Of the distance the Choctaw had to cover on foot, nearly 50 kilometers were under water. After four days, the survivors of the march reached Little Rock. There they were provided with medicine, food and clothing and joined the Armstrong group.

Resettlement in autumn 1833 and expulsions after 1833

The third and last relocation ordered by the government took place the following year. Gaines opted for the route via Vicksburg again, but unlike in previous years, only around 1000 Choctaw showed up at the collection points in October. The heavy rains did not occur this year and the move to the Indian territory went as planned.

For the 6000 or so Choctaws remaining in Mississippi, conditions deteriorated noticeably. The promised civil rights proved insufficient to protect the Indians; they have repeatedly been the target of racially motivated assault, persecution and dispossession. In 1836 another group of about 1000 Choctaw decided to move to Indian territory, 1600 followed a year later and other smaller groups left Mississippi because of the deteriorating living conditions in the following years and decades. Around 1910, only around 1250 Choctaw lived in the original tribal area. The descendants of the remaining Indians were combined in the 1940s in accordance with the Indian Reorganization Act (English for law for the reorganization of the Indians ) as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and received their own reservations in Mississippi.

Estimated losses

Exact figures on the Choctaw displaced are not available. Based on around 15,000 resettled people, various estimates come to the conclusion that around 2,500 people died during the treks carried out by the government alone. How many of the displaced people died on the way to the assembly points, after arriving in Indian territory or during later resettlements is not recorded.

Muskogee

Disintegration of the Confederation

In the mid-18th century, the Muskogee , referred to as the Creek by the settlers , were one of the most powerful and influential nations in the south. The confederation of various tribes, including the Coushatta , Yamacraw , Shawnee, and Alabama , had at least 40 villages in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Florida, and an estimated force of 1,250 to 6,000 warriors. During the course of the American War of Independence towards the end of the century , the confederation broke up in the course of the approximation of the way of life of the white settlers, which was differently accepted and implemented in the tribes . The tribes of the "Upper Creek" (English for Upper Creek ) in the Alabama Valley , who lived further away from the colonies, rejected acculturation. They sided with the British during both the American Revolution and the British-American War . Your former ally who at Chattahoochee , Ocmulgee and Flint River settled close to the Whites "Lower Creek" (English for Lower Creek ), behaved largely neutral or pro-American. The conflict culminated in 1813 and 1814 in the " Red Stick War " (English for War of the Red Sticks ), a civil war between the anti-American and the willing party within the Muskogee. With the victory of pro-American Muskogee and American militia supporters under Andrew Jackson in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , the traditionalists' resistance was finally broken and they surrendered in August 1814.

Land assignment agreements

Jackson used the situation after the Civil War to force the defeated Upper Creek and its allies Lower Creek, which he accused of participating in the rebellion, to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson in August . In this treaty, the Muskogee gave the rights to over half of their land, around 81,000 square kilometers (an area the size of Austria ), to the United States. The state of Alabama emerged from this area. Individual tribes of the Muskogee gradually sold more land, although the Muskogee government threatened the sale of additional tribal areas with the death penalty. For example, William McIntosh and other Muskogee leaders signed the Indian Springs Treaty on February 12, 1825 , ceding large parts of the remaining territory to Georgia. Shortly after ratification of the treaty, McIntosh was killed in May of the same year by a group of Muskogee around Menawa because of the cession, which was viewed as treason.

The Muskogee Council, led by Opothleyahola, successfully protested the treaty. A new agreement, the Washington Treaty of 1826, repealed the previous treaty. This makes the Indian Springs Treaty the only ratified treaty between the United States and an Indian nation that has ever been annulled. However, the Georgian government refused to recognize the cancellation made in 1826 and continued the evictions. Without further interference from the federal government, the Lower Creek were forcibly evicted from their tribal areas and moved into Indian territory in small groups.

The remaining 20,000 or so Upper Creek in Alabama were further restricted by state law, for example, they were banned from establishing sovereign tribal governments. In a further protest note, the Upper Creek asked Jackson, who has now been elected president, for help. Instead, however, they were forced to sign the Treaty of Cusseta , which divided the Muskogee's territory into individual parcels. The government and the squatters invading Indian land were thus given access to the tribal areas without having to adhere to the superordinate treaties of the federal government. Pressure was increasing on the Indian landowners. Looting took place and farms were set on fire to drive individual families off their land. The conflict between the Muskogee and the white settlers finally culminated in the Creek War of 1836 . The fighting between the parties was brought to an end, with the help of the military, through the forced relocation of the remaining Muskogee, covered by the Indian Removal Act.

Sequence of resettlements and evictions

After the ratification of the Indian Springs Treaty in 1825, smaller, affluent groups, most of whom came from the McIntosh family, left their territory westward. In total, about 1000 to 1300 Muskogee emigrated with their slaves to settle in the Arkansas Valley , the area of Indian territory allocated to them. This enabled them to secure preferred and agriculturally attractive properties and created a good starting point for their individual wellbeing. Other groups and survivors of the Red Stick War joined the Seminoles or relatives in the areas not yet affected by the displacement.

Following the Creek War of 1836, around 2,500 Muskogee were rounded up in Alabama and brought to Montgomery, Alabama . Among them were a few hundred warriors who were tied up and transported away under heavy guard. This group was deported over the Alabama River , on which the Muskogee were brought downstream to the Gulf of Mexico and then over the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers to Fort Gibson in Indian territory. This route was followed in 1836 and 1837 by a further 14,000 Muskogee, who were hardly allowed to take more than what they were wearing. During the three-month transport in different, staggered treks, they suffered from the very hot summers, the snowstorms in winter and various epidemics. An eyewitness described how, during one of these resettlements, several Indians froze to death or collapsed from exhaustion while their relatives were not allowed to bury their dead or perform the necessary rites.

Another group of around 4,000 women, the elderly and children was rounded up in camps in March 1837. Their families had been promised by the government that they would be exempt from resettlement if their husbands fought on the side of the United States in the Seminole War. By the time they got to their families in September, many of the internees had died of rampant diseases due to the conditions in the camps. The survivors also followed the route via New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico; 311 deportees were killed in the wreck of one of the unseaworthy ships that transported them. Most of the displaced people settled in the area around what is now Okmulgee, Oklahoma . After a period of strained relations between the Upper and Lower Creek in the new territory, the covenant was renewed and the sovereign Muskogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma was formed.

A few families remained in Alabama, their descendants today form the Poarch Band of Creek Indians , which was the only Indian tribe in Alabama to receive state recognition. Most of them live in the Poarch Creek Reservation in Escambia County .

Estimated losses

There are no clearly documented figures regarding the displacement and the resulting losses of the individual tribes of the Confederation. How many of the Muskogee originally living in the southeast were actually expelled is unknown; only the numbers recorded by the Indian agents as part of the state resettlement are certain. According to a statement by the officer in charge of the United States published in the Arkansas Gazette on January 17, 1838 , the entire population of 21,000 was largely resettled without any problems. Immediately after the resettlement, at least 3,500 people died of diseases known as "lung fever". It is unclear how many Muskogee bowed to the pressure of the settlers or the states and made their way in small family groups to relatives in the swamps of Florida or into Indian territory. It is also not known how many Indians died in the camps or during the military conflicts before the treks began. The anthropologist Russell Thornton assumes on the basis of in-depth research that about 50 percent of the people were destroyed by the direct and indirect consequences of the displacement.

Chickasaw

Voluntary land assignment

The Chickasaw , a numerically small people with around 5,000 tribesmen and 1,200 slaves, settled in the states of Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee. After the Indian Removal Act was passed, they recognized the hopelessness of the situation at an early stage and decided to voluntarily relocate in order to achieve the best possible starting point for the welfare of their nation. After a first land assignment treaty , the Treaty of Old Town of 1818, the Chickasaw Council signed the Treaty of Franklin in 1830 . It agreed to exchange appropriate areas in the west for the original land of the Chickasaw. The agreement was not ratified by the United States Congress because the tribe could not be offered an appropriate area in Indian territory. The Chickasaw's first expeditions were sent west to prepare for the resettlement.

With the Treaty of Pontotoc , another, not yet ratified, treaty was negotiated in 1832, which regulated the sale of the approximately 26,000 square kilometers Chickasaw areas for three million dollars (the area corresponds to the size of Sicily ). In 1834, the Treaty of Washington was followed by another agreement that made the previous treaty valid, although no new areas in Indian territory were available for the Chickasaw.

Settlement area in the Choctaw Territory

After several expeditions between 1832 and 1837, negotiations with the Choctaw, whose government-allocated section of Indian territory was the preferred settlement area for the Chickasaw, repeatedly failed. Under pressure from the government trying to speed up the relocation, the Chickasaw and Choctaw signed the Doaksville Treaty, despite their strained relations . In the agreement signed on January 17, 1837, the Chickasaw received the right to settle in the west of the Choctaw area, today's southwestern Oklahoma, in return for payment of $ 530,000. The Chickasaw's original plans to buy the land to build a sovereign nation were thwarted. They received the area only on loan, in addition they were allowed to represent their interests in the council of the Choctaw.

Relocation

Already at the beginning of the relocation initiated by the government, smaller family groups, especially those from the affluent class, moved to the Indian territory and thereby secured individual areas in preferred locations at an early stage. Government resettlement of 3,001 tribesmen and slaves began in the summer of 1837. Under the direction of AMM Upshaw and John M. Millard, the Chickasaw were moved to Memphis on July 4, 1837. From there they were to move west along the routes already used by the Choctaw and Muskogee. In contrast to the previous resettlements, the resettlement of the Chickasaw was planned much more carefully. Sufficient supplies and accommodation were available along the route. The Chickasaw were allowed to use livestock as well as their own ponies and carts to transport their belongings. Some of the clans decided to set up their own groups, who moved into Indian territory without the supervision of government officials, and paid for their resettlement from a fund made available by the tribal government. These self-organized and financed treks cost the nation around $ 100,000, with the Chickasaw assuming government payments would arrive soon.

Contrary to what the Chickasaw Council had planned to rebuild the nation in the west, many of the displaced tribesmen settled near existing Choctaw villages. The people subsequently lost their independent identity and became part of the Choctaw nation. It was not until 1854 and after further sums were paid to the Choctaw that the Chickasaw succeeded in regaining their own constitution. The descendants of some non-resettled Chickasaws, mostly widows and orphans whose resettlement was not financed, form the Chaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People of South Carolina, recognized by South Carolina in 2005 .

Estimated losses

The losses of the Chickasaw during the various treks were relatively small due to the good preparation and the available funds. However, at the beginning of the resettlement there was a smallpox epidemic among the population and after the resettlement there were repeated conflicts with the ancestral peoples already living in Indian territory. In total, around 500 to 600 Chickasaw were killed as a result of the resettlement and its consequences.

Cherokee

Population growth and gold rush

The Cherokee populated areas in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. The tribes, which were largely adapted to the way of life of the whites, were pushed back by the enormous increase in the population of white settlers until about 1820, but were able to keep their tribal areas and reservations guaranteed by treaties. However, after the first gold discoveries in Dahlonega , Georgia in 1829 , which sparked the first gold rush in the United States, the attitude of the Georgian government towards the indigenous people living in the area changed. The government passed laws that deprived the Cherokee of various rights, including mining rights for their own land. This was done on the basis of various reasons, for example the official claim that Indians were unable to manage their lands effectively and that whites could use them better. Later studies have shown that the Cherokee were experiencing an economic upswing at this point in time and that agricultural techniques from Europe were beneficially adapted and used.

Legal action against Georgia

The Cherokee tried to legally improve their situation and forbid the states to intervene in the settlement area and to protect their individual rights. They went to the United States Supreme Court on the Cherokee Nation v Georgia case in June 1830, under the direction of John Ross, a well-respected Cherokee chief. The Cherokee were supported by several congressmen, including Davy Crockett , Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen , on whose proposal William Wirt took over the legal representation of the case. Wirt moved for the annulment of all Georgia laws that restricted the law of the sovereign nation of the Cherokee. However, the Supreme Court dismissed the case on the grounds that there is not at the Indians to an independent state, but (for English a "domestic dependent nation" an indigenous and dependent nation ) that could sue as such no rights. However, the Supreme Court indicated that it would accept and rule other cases that would be referred by a state court for appeal on behalf of the Indians.

As a result of this rejection, the Cherokee tried to enforce their rights through a civil lawsuit. In the Worcester v Georgia case , the 1832 Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee, as announced. The reasoning presented by Chief Justice John Marshall stated that a state did not have the right to intervene in the internal affairs of Indians or to dispose of their territory. However, the judgment came too late, the Indian Removal Act had already come into effect and was implemented by Jackson in disregard of the judge's decision. These two decisions continue to influence American government policy toward Native American people to this day.

Treaty of New Echota

In view of the external threats to the nation, which sees itself as sovereign, internal political differences arose over the question of resettlement. John Ross, behind whom with about 17,000 Cherokee stood the far greater part of the people, argued against resettlement and any voluntarily signed agreement that favored it. In his view, the Cherokee were spiritually and culturally inextricably linked with the land of their ancestors, and survival of the people was only possible there. This position was supported by about 500 tribal members "Treaty Party" (English for contracting party ) to Major Ridge , who campaigned for a voluntary resettlement. Its representatives understood the nation as a social union of people whose survival was not ensured by the country, but by their existence as a people. They saw this security, which was also influenced by economic factors, in the voluntary resettlement in Indian territory.

Members of the Treaty Party, including Major Ridge and his son John Ridge, signed the Treaty of New Echota on December 29, 1835, against popular resistance . In this contract, the assignment of all Cherokee areas east of the Mississippi for $ 5 million and the allocation of new settlement areas in Indian territory were agreed. John Ross penned a protest note, which he personally took to Washington, DC , where he made it clear that neither the nation's elected leaders nor the vast majority of the people supported the treaty. Although prominent advocates supported him in Congress and Ross presented a list of 15,000 signatures against the treaty, the agreement was ratified on May 23, 1836 with just a one-vote majority. The forcible relocation of the Cherokee became lawful. May 23, 1838 was decided as the date of resettlement. While Ross was putting forward his views in front of Congress and fighting to preserve the eastern tribal areas for the Cherokee, the members and supporters of the Treaty Party and Major Ridge's family moved west.

Rounding up the Cherokee

After the ratification of the Treaty of New Echota, the military began with the help of volunteers in the south with the construction of several forts surrounded by palisades . These prisons, also known as concentration camps in literature, were intended to accommodate the Cherokee until they were transported to Indian territory; they were poorly equipped with accommodation and provisions. Many of the soldiers and also several officers sympathized with the Cherokee and refused to participate in the deportation. After several rejected appeals, General Winfield Scott finally took on the task of rounding up the Cherokee with the help of 7,000 soldiers sent from the north. The Cherokee, who made no effort to prepare for the move, were ordered by force of arms from May 17, 1838, to move the camps in Gunter's Landing, Ross's Landing and Hiwassee Agency or, for example, the forts Lindsey, Scott, Montgomery, Butler in North Carolina, Gilmer, Go to Coosawatee, Talking-Rock in Georgia, Cass in Tennessee or Turkeytown in Alabama. Sometimes the Indians only had an hour to pack their belongings. After ten days, known as "Cherokee Round-ups" (English for [cattle] round up ), the Cherokee had mostly been taken to the camps. The horses and cattle of the deportees were expropriated and sold by Indian agents or soldiers. Some families were torn apart by the round-ups and could not be reunited even after the resettlement. A part of the Cherokee, about 1000 to 1100 people, managed to flee and hide in the inaccessible mountain regions of the Appalachians or to find refuge in the countryside, especially for Scottish settlers. Their descendants now form the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians .

Cherokee Trail of Tears

Around 13,000 interned Cherokee spent the summer in the camps. Disease was rampant and white traders smuggled alcohol into the forts, which made the situation even worse. Some historians assume that more Cherokee died at this stage of the relocation than on the way to the new settlement areas. After Ross returned from Washington, he convinced those responsible to hand over the Cherokee resettlement to the tribal government. He planned the resettlement in 13 groups of 1000 people each. With this decision Ross avoided the evacuation of the Cherokee in a single large trek that could hardly have been supplied. This prevented additional losses that would have been expected from undersupply and illness. The groups left the camps in the fall of 1838, the last trek led by John Drew left the east on December 5, 1838.

The conditions under which the Cherokee referred to as the “March of the Thousand Miles” relocation began were catastrophic. The Cherokee refused to leave the camps and their homes. They were forced to move at gunpoint and blows. Due to the round-ups, they started the resettlement very poorly prepared and in poor health due to the long stay in the camp. The loading of a small part of the Cherokee onto ships and the departure of others on foot resulted in further separations of families. The two main routes of the Cherokee represent the northernmost resettlement routes of the Indian resettlement routes. On both routes, on the one hand on the march over Tennessee, Kentucky, through southern Illinois and Missouri , on the other hand on the waterway over the rivers Tennessee , Ohio , Arkansas and Mississippi, the Cherokee suffered winter storms with temperatures well below freezing. In addition to deaths from freezing to death, malnutrition caused by very limited rations, accidents and exhaustion, other tribe members died of diseases such as measles , cholera, whooping cough and dysentery . This particularly affected the children and the elders of the people, for whom the up to six-month walk into the Indian territory, which is almost 2,000 kilometers away, was almost impossible to manage. Accompanying soldiers were shocked by the brutality of the march, for example a volunteer from the Georgia militia described the deportation in retrospect, despite his later experience in the American Civil War, as "... the cruelest work I have ever seen." The Cherokee refer to the resettlement as " Nunna daul Tsuny ”(Cherokee for The Way We Wept ). As the most loss-making of the deportations, it epitomized the expulsion of Indian nations from the southeast.

Estimated losses

The Cherokee strove to self-document their losses throughout the relocation. However, in many cases they did not succeed in keeping up with developments, and ritual burials and farewell ceremonies were only possible in a few cases. Subsequent investigations and the evaluation of the various government transport lists suggest that the number of victims was at least 4,000, although the number is likely to be around 8,000, according to recent research. This estimate also takes into account the Cherokee who died in the camps. Further deaths occurred after arriving in Indian territory. These include deaths caused by conflict with other peoples or previously relocated Cherokee, and the council-decided execution of male members of the Ridge family and other signatories of the New Echota Treaty.

Seminoles

Payne's Landing Contract

The heterogeneous group of Seminoles lived in a reservation in central Florida after the sale of Spanish Florida to the United States in 1823. In addition to older tribes from the region such as the Apalachicola or the Timucua, it also consisted of various family clans and refugees from the Muskogee. Much of the nation consisted of African-American or mixed-race slaves, or ex-slaves released or escaped from the north. The swampy interior of Florida was not suitable to feed the people living in the reservation, which is why they hunted and procured supplies mainly in the north of their settlement area. The settlers living there viewed the invading Seminoles with great suspicion. This was particularly due to the close connection between the Indians and the Afro-Americans living with them. Although there was no economic interest in the reservation area on the part of the white settlers, around 1830 they pushed for the Seminoles to be resettled.

Hunger, poor harvests and the lack of economic prospects convinced the Seminole leadership to start contract negotiations with the government. According to the will of the United States, the Seminoles should join the Muskogee in Indian territory and return all runaway slaves to their owners. In the treaty of Payne's Landing of May 9, 1832, the abandonment of the reservation against new areas in Indian territory was finally determined. As a prerequisite for ratification, it was established that suitable areas for the Seminoles could be found in the Indian territory. To find such areas, a delegation of the Indians traveled to the west. After the expedition ended in the spring of 1833, the seven participants were forced to sign the Fort Gibson Treaty while still in Indian territory. This confirmed that the Seminoles had found suitable land in the west and enabled Congress to ratify the Treaty of Payne's Landing in April 1834. This happened without further information and consultation of the Seminoles in Florida. The deportation was to be carried out by 1835.

Second Seminole War

The various groups within the Seminoles refused to obey the resettlement request. In their opinion, they were not adequately involved in the decision. In addition, there were concerns about having to join a people who were strange to them. The fear of influential African American groups and the Black Seminoles also influenced this refusal. An integral part of the tribes, Afro-Americans feared being enslaved for the first time or again. The resistance of the Seminoles culminated at the time of the planned resettlement in January 1836 in the Second Seminole War. The war dragged on until the death of Osceola , the most important leader of the Seminoles, in 1842. This war is considered to be the longest and most expensive Indian war in United States history. It killed 1,500 American soldiers and an unknown number of white and Native American civilians and devoured over $ 30 million. Seminoles captured during the war were deported to Indian territory.

Relocation after 1842

After the end of the Second Seminole War, around 4,000 Seminoles and their allies of African American descent were tracked down, hunted and rounded up in the swamps with the help of the military. They were detained in two camps in the Tampa , Florida area. The women and children there suffered particularly, as there were hardly any rations or clothing available for them. Whites gained access to the camps with the help of the military commanders and tried to detach runaway slaves and Indians of African American descent from their family associations and to transfer them into white slavery , which succeeded in several cases. The Seminoles were gradually shipped in small groups by steamboat across the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans. There they followed the waterway over the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers to Fort Gibson in the Muskogee area in Indian Territory. However, they did not become part of the Muskogee nation, but formed the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. This nation also includes two tribes of the Black Seminoles, who today call themselves "Freedmen" (English for liberated people ). Several hundred Seminoles hid in the Everglades to avoid deportation. These did not submit to the American government in the Third Seminole War (1855-1858). As a result of this war, another 200 prisoners were deported. The descendants of the Seminoles that remained in Florida now form both the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida .

Estimated losses

Little is known about the losses of the Seminoles, whose resettlement and expulsion dragged on from 1820 to around 1850. In total, of the almost 5000 Indians settling in Florida, an estimated 2833 were resettled, which means that they arrived in Indian territory. How many died in the camps, on the way west, or fell into white slavery is unknown. The number of Seminoles killed in the Second Seminole War is also not documented; the surviving group, who settled in the Florida swamps and permanently evaded resettlement, comprised 250 to 500 people.

Consequences of displacement

Living conditions in the reserves

The tribes traumatized by the forced resettlement and the numerous casualties encountered a largely alien world in Indian territory. The environmental conditions in the rather barren Indian territory differed significantly from the very fertile and infrastructurally well developed settlement areas from which the peoples came. The "civilized nations", strongly adapted to the way of life of the whites, lived in fear of what they believed to be "wild tribes", as they called the original inhabitants of the country. There were repeated conflicts and battles with the nomadic living Plains Indians , including for example the Sioux , Cheyenne , Comanche and Blackfoot were. Their settlement areas and habitat were restricted by the arrival of around 100,000 Indians from the southeast. This initially led to a crowded settlement of the deportees around the larger cities and forts, through which the newcomers promised protection from the Plains Indians, but also to increasing problems among the various tribes. The situation was exacerbated by the lack of arms deliveries, which the resettled tribes had been assured of for self-defense by the United States.

In addition to losses due to these hostilities and clashes among the resettled and sometimes hostile peoples, there were hundreds of other deaths in the first phase of resettlement. This was caused on the one hand by diseases that grew into epidemics among the exhausted people, on the other hand by the poor timing of the resettlement. The late arrival prevented early sowing, resulting in hunger and poor harvests. The government's food deliveries to cope with these failures either failed to materialize or were insufficient to feed the Indians.

The unification of the Seminoles with the Muskogee and the Chickasaw with the Choctaw, as demanded by the government, was vehemently rejected by these peoples. The amalgamation of the settlement areas turned out to be unsustainable and led to further treaties that enabled a clear mutual delimitation and separation of nations. Further resettlements within the Indian territory, which particularly affected the Seminoles, led to the pacification of the conflicts. In the peaceful phase that followed after 1856, the peoples recovered economically, albeit very slowly in some cases. Although the economic situation of the Indians remained significantly worse than before the resettlement, this served the supporters of the Indian Removal Act as confirmation that the losses suffered by the Indians had ultimately led to a good end and that the expulsions in the interests of the Indians had been positive.

Political and economic consequences

The personal losses that each of the deported families had literally suffered, and the cultural and spiritual uprooting, led to an attitude that was commonly described as apathy. This prevented many of the resettled people from gaining a foothold in the initial phase and lasted up to thirty years in some tribal associations. It was only after that that those affected began to break free of government dependency on food deliveries and payments and to rebuild their nations in the West.

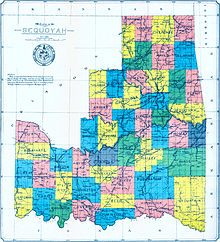

In some peoples, tensions arose between those who were voluntarily resettled in the early phase of displacement, the “old settlers”, and those who were later deported with regard to the question of the government and justice system. Contrary to the prognoses of the white opponents of the Indian Removal Act, however, it did not dissolve and decay; rather, all peoples succeeded in regaining their sovereignty and establishing a political system by the middle of the 19th century. Similar to the individual legal systems, this was based on the model of the forms of government already used in the East and influenced by American and European countries. Towards the end of the 19th century, parts of the area that had been guaranteed "forever" to the Indians were released for settlement by white settlers during the " Oklahoma Land Run ". In order to prevent the further restriction of their settlement areas and a new expulsion, the five civilized nations tried to form a federal state. The state was to be named Sequoyah in honor of the inventor of the Cherokee written language . After the application for recognition of the state was rejected, the Indian Territory united with the neighboring Oklahoma Territory. Together they founded the state of Oklahoma.

At the time of resettlement, the peoples had adopted the European understanding of land as an economic asset, a fundamental change in their attitude towards the traditional religious and spiritual respect for land. In this dichotomy, they lived mostly on family-owned farms, grew various types of grain and vegetables and largely gave up hunting in favor of keeping domesticated animals. The economic progress of the individual families was mainly determined by the location and quality of the settlement areas. For example, for some of them, the construction of the Oklahoma railroad brought additional income from the sale of timber, while others made wealth through the mining of coal and iron ore. Other influencing factors were attitudes towards slavery, which was used for the effective management of the farms, and the dependence on the United States, as well as the amount of their maintenance payments to the Indians. The majority of the Indians arrived, however, completely destitute in the Indian territory because of the circumstances of their deportation. It was not until well into the middle of the 20th century that they recovered economically and were able to maintain themselves on their reservations, for example through tourism and casinos, without the assistance of the United States.

Spiritual and cultural changes

The peoples of the Southeast saw themselves in close connection with the land on which they lived. It was an integral part of their spiritual and cultural identity. When they were expelled, they initially lost this connection to their environment. This was intensified, for example, by the ban on relocating the bones of their ancestors. Stones carried in secret became the greatest possession of the resettled and represented the ideal connection to the lost homeland. During the phase of resettlement and resettlement in the Indian territory, the peoples were accompanied very intensively by Christian missionaries. Daily Bible readings, church services and Christian songs partly supplanted the Indian ceremonies and became part of the indigenous culture. In the case of the Cherokee, for example , this is evident from the unofficial national anthem of the people, “ Amazing Grace ”, which does not come from their original culture but was introduced by the missionaries during the path of tears. Although almost completely Christianized, the peoples managed to maintain central rites and ceremonies, for example the "Green Corn Dance" of the Choctaw and Muskogee, and to set up new ceremonial and burial sites that were integrated into their newly acquired Christian identity.

In order to promote further acculturation in the sense of whites, the Indians were forbidden by various state regulations from cultivating their culture. This included a ban on speaking their languages and the children were forced into state schools to assimilate white culture from an early age. Traditionally anchored concepts such as the passing on of Indian knowledge about the use of medicinal plants, conventional craftsmanship, but also the matrilineal structure of many tribes and the oral transmission of Indian history were made more difficult, in some cases partially or completely suppressed. Despite these measures, the Indian culture could not be permanently displaced. The tribes preserved their cultural and spiritual origins and made various efforts, for example to preserve their languages and ceremonies or to re-establish them at a later date.

Research, reappraisal and commemoration

research

In the late-onset research in the 1970s, the work of Grant Foreman initially placed an emphasis on the collection of facts. For example, the relevant government documents were evaluated, including loading and transport data; The first reliable figures on the deaths come from this research. This was followed by important insights into the political and social factors, both within the peoples and in the course of the federal government's Indian policy. These factors continue to be the subject of research on the path of tears. Towards the end of the 1980s, Russell Thornton reassessed the events with regard to the number of victims and the Indian persecution, after which he concentrated his investigations in particular on the Cherokee and their population development. Meanwhile, the cultural consequences of resettlement are increasingly being explored, including adaptation, rediscovery of spiritual identity, and achieving a balance between Native American origins and white influences. Historian Clara Sue Kidwell rates research on this subject as not yet completed. Part of the archaeological research, which in many cases is co-financed by members of the tribes, deals with the search for the unmarked graves along the path of the tears. Universities, including the Southern Illinois University Carbondale , work together with both the Indian nations and the National Park Service . Other projects supported by the National Park Service deal with the investigation and preservation of individual historical sites, certain sections of the route or the documentation of the interrelationships and their preparation for museums, schools and other public institutions. Extensive archives are maintained for research and documentation purposes, such as the Native American Press Archive of the Sequoyah Research Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock .

Indian controversy and memory

The displaced peoples initially orally preserved the history of resettlement and migration into Indian territory and passed it on to their descendants as part of their individual tribal history. In individual cases, the stories were recorded in writing by contemporary witnesses, but many Indians refused to use the written language. Most of the novels, songs and stories that deal with the resettlement and the coming to terms with personal fates therefore come from the descendants of the survivors. One of the best-known oral traditions is that of the Cherokee rose , a type of rose that grows widespread in the southeast and has been named the state flower of Georgia. According to legend, every tear weeping during the expulsion became such a rose; their white color refers to the mourning of the mothers, the seven leaves on the stem are reminiscent of the seven displaced tribes of the Cherokee and the yellow inflorescence symbolizes the gold that cost the Cherokee their homeland.

While the processing of the path of tears within white culture and art does not play a role in comparison to the myth of the “ Wild West ”, the artistic examination of the loss of the original settlement areas within indigenous art is of great importance. In addition to pictures and drawings, new media such as films, videos and the Internet are used by the descendants of the resettled Indians, who are known as “ survivors ”. The personal confrontation with the individual family past often takes place through hiking or traveling, similar to pilgrimages , along the resettlement routes.

Government attitude

In 2000, the outgoing director of the expressed Bureau of Indian Affairs (English for Bureau of Indian Affairs ) his regret and put the responsibility of his authority for the injustice suffered is, however, the US government distanced itself from these statements. Another attempt to get the United States to issue an official statement was made in 2004 by Senator Sam Brownback . He submitted Joint Resolution 37 to the Senate , which provides for an official apology for past Indian policy.

The American government had not publicly apologized for more than two centuries of Indian policy until 2009, although debates had begun. In 2009, the government and tribal officials reached an agreement on compensation for the economic use of the reservations since 1896. On December 19, 2009, President Barack Obama finally signed a statement, without significant media attention, in which he spoke “on behalf of the people of the United States to all indigenous people (Native peoples) for the many incidents of violence, mistreatment and neglect inflicted on Native peoples by citizens of the United States.

Various sites relevant to the resettlement have now been declared National Historic Sites (National Monuments) and two routes of the Trail of Tears have been included in the National Trails System (routes of national importance) .

Memorials, National Historic Sites, and Trails System

To commemorate the events and losses in the context of the displacement and resettlement of the southeastern peoples, the United States Congress decided in 1987 to establish the "Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail" as part of the National Trails System and its administration through the National Park Service . The trail extends for around 3,540 kilometers and leads through nine states. Two Cherokee resettlement routes were selected, one following the waterway, the other following the land route to the west. There are several memorials, state parks, and places of particular historical interest along these two routes . These include, for example, the “Junaluska Memorial and Museum”, an important burial site and memorial for the seven displaced Cherokee tribes in Robbinsville (North Carolina) , “The Hermitage” not far from Nashville (Tennessee), the former home of Andrew Jackson, in which exhibitions on Indian politics are shown, and the "North Little Rock Riverfront Park" in North Little Rock (Arkansas), where several resettlement routes crossed. Other attractions along the trail include the "New Echota State Historic Site" in Calhoun (Georgia) , the "Trail of Tears State Park" near Jackson (Missouri) and the "Fort Gibson Military Site" in Fort Gibson (Oklahoma). A sculpture by a Danish sculptor was set up in Tulsa , Oklahoma in 2016. In addition to the parks and memorials maintained by government organizations, there are various privately owned museums, monuments and historical buildings along the trail that deal with the history of the Indian expulsion and the resettled nations. The inclusion of further sections in the official course of the "Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail" is planned.

Trivia

The pop song Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian) , written by John D. Loudermilk and successful in the European and American charts in two different cover versions in the 1970s, refers to the historical process of the deportation of the Cherokee . The subject is also taken up in the songs "Cherokee" by Europe and "Creek Mary's Blood" by Nightwish as well as "Trail of Tears" by WASP and in the album Trails of Tears by Jacques Coursil .

literature

General representations

Basics

- John P. Bowes: The Trail of Tears: Removal in the South . Ed .: Paul C. Rosier. Chelsea House Pub., 2007, ISBN 0-7910-9345-X (English).

- Raymond Fogelson, William Sturtevant: Handbook of North American Indians . tape 14 . Smithsonian Institution, 2004, ISBN 0-16-072300-0 (English).

- Grant Foreman: Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians . University of Oklahoma Press, 1974, ISBN 0-8061-1172-0 (English).

- William Thomas Hagan: American Indians . 3. Edition. University of Chicago Press, 1993, ISBN 0-226-31237-2 , pp. 95-98 (English).

- Bruce E. Johansen: The Native Peoples of North America: A History . Rutgers University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8135-3899-8 (English).

- AJ Langguth: Driven West: Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears to the Civil War . Simon & Schuster, 2010, ISBN 1-4165-4859-9 (English).

- Russell Thornton: American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 . University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2220-X (English).

- Elliott West : Trail of Tears: National Historic Trail . Western National Parks Association, 1999, ISBN 1-877856-96-7 (English).

- Aram Mattioli : Lost Worlds. A History of the Indians of North America 1700–1910 . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2017 ISBN 978-3-608-94914-8 .

Social, cultural and political backgrounds

- Duane Champagne: Social change and cultural continuity among Native Nations . Rowman Altamira, 2006, ISBN 0-7591-1001-8 (English).

- Duane Champagne: Social order and political change: constitutional governments among the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Creek . Stanford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-8047-1995-0 (English).

- Tim Alan Garrison: The Legal Ideology of Removal: The Southern Judiciary and the Sovereignty of Native American Nations . University of Georgia Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8203-2212-1 (English).

- Thomas N. Ingersoll: To Intermix with Our White Brothers: Indian Mixed Bloods in the United States from Earliest Times to the Indian Removal , Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2005

- Francis Paul Prucha: American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly . University of California Press, 1997, ISBN 0-520-20895-1 (English).

- Francis Paul Prucha: The Great Father. The United States Government and the American Indians . University of Nebraska Press, 1986, ISBN 0-8032-8712-7 (English).

- Robert V. Remini: Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars . Viking, 2001, ISBN 0-670-91025-2 (English).

- Bruce G. Trigger, Wilcomb E. Washburn et al .: The Cambridge history of the native peoples of the Americas . Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-521-57392-0 (English).

History and Displacement of Individual Nations

Choctaw

- Sandra Faiman-Silva: Choctaws at the Crossroads: The Political Economy of Class and Culture in the Oklahoma Timber Region . University of Nebraska Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8032-6902-1 (English).

- Marcia Haag, Henry Willis (Ed.): Choctaw Language and Culture: Chahta Anumpa . University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8061-3339-2 (English).

- Valerie Lambert: Choctaw Nation: A Story of American Indian Resurgence . University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8032-1105-8 (English).

Muskogee

- Angie Debo: The Road to Disappearance: A History of the Creek Indians . University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-1532-7 (English).

- Michael D. Green: The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis . University of Nebraska Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8032-7015-1 (English).

- Sean Michael O'Brien: In bitterness and in tears: Andrew Jackson's destruction of the Creeks and Seminoles . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-275-97946-6 (English).

Chickasaw

- Horatio Bardwell Cushman, Angie Debo: History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez Indians . University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8061-3127-6 (English).

- David Fitzgerald, Jeannie Barbour, Amanda J. Cobb: Chickasaw: unconquered and unconquerable . Graphic Arts Center Publishing, 2006, ISBN 1-55868-992-3 (English).

- Arrell Morgan Gibson: The Chickasaws . University of Oklahoma Press, 1971, ISBN 0-8061-1042-2 (English).

Cherokee

- Theda Perdue, Michael D. Green: The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears . Viking, 2007, ISBN 0-670-03150-X (English).

- Vicki Rozema: Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation . 2nd Edition. John F. Blair Publ., 2007, ISBN 0-89587-346-X (English).

- Russell Thornton, C. Matthew Snipp, Nancy Breen: The Cherokees: A Population History . University of Nebraska Press, 1992, ISBN 0-8032-9410-7 (English).

- Thurman Wilkins: Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People . 2nd Edition. University of Oklahoma Press, 1989, ISBN 0-8061-2188-2 (English).

Seminoles

- Edwin C. McReynolds: The Seminoles . University of Oklahoma Press, 1957, ISBN 0-8061-1255-7 (English).

- Kevin Mulroy: Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas . Texas Tech University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-89672-516-2 (English).

- Sean Michael O'Brien: In bitterness and in tears: Andrew Jackson's destruction of the Creeks and Seminoles . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-275-97946-6 (English).

Web links

- The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (English) - Official website, including the history of the nation

- The Muscogee (Creek) Nation (English) - Official website, including a brief historical summary of the nation's history

- The Chickasaw Nation (English) - Official website, including a brief historical outline of the nation's history

- The Cherokee Nation (English / cherokee) - Official website, including a presentation of the history of the nation and the important leaders of the tribes

- The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma (English) - Official website, including the history of the nation

- National Park Service: Trail of Tears National Historic Trail (official site; English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Russell Thornton, C. Matthew Snipp, Nancy Breen: The Cherokees: A Population History . University of Nebraska Press, 1992, ISBN 0-8032-9410-7 , Resurgence and Removal: 1800 to 1840, pp. 47-80 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e Len Greenwood: Trail of Tears from Mississippi walked by our Choctaw ancestors . In: Judy Allen (Ed.): The Bishnik . March 1995, p. 4 (English, magazine of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma).

- ↑ a b c d e Sandra Faiman-Silva: Choctaws at the Crossroads: The Political Economy of Class and Culture in the Oklahoma Timber Region . University of Nebraska Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8032-6902-1 , pp. 19 (English).

- ↑ John Burnett, The Navajo Nation's Own 'Trail of Tears' on National Public Radio June 14, 2005. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ^ Stanley M. Elkins, Eric L. McKitrick, The Age of Federalism . Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-19-509381-0 , VI, pp. 214-222 (English).

- ↑ See, for example, the Cherokee Land cession table in Russell Thornton, C. Matthew Snipp, Nancy Breen: The Cherokees: A Population History . University of Nebraska Press, 1992, ISBN 0-8032-9410-7 , Table 6. Nineteenth-Century Cherokee Eastern Land Cessions, pp. 55 (English). or the Chickasaw in Colin Gordon Calloway: The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities . Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-47569-4 , Tchoukafala: The continuing Chickasaw struggle for Independence, pp. 213-243 (English).

- ^ Bruce E. Johansen: The Native Peoples of North America: A History . Rutgers University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8135-3899-8 , The Explosion Westward: The Accelerating Speed of Frontier Movement, pp. 181-218 (English).

- ↑ An overview of the Moravians' missionary work among Indian tribes is available online in the Wheaton College archives under Records of Moravian Missions Among American Indians. (No longer available online.) In: Billy Graham Center. Wheaton College, archived from the original on May 9, 2008 ; Retrieved April 20, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The importance of John Ross for the development of acculturation and resistance to displacement is for example in Theda Perdue, Michael D. Green: The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears . Viking, 2007, ISBN 0-670-03150-X (English). or in John Ross-Chief of the Cherokee biography made available online by the Georgia Tribe of Eastern Cherokee (accessed March 10, 2009).

- ^ Duane Champagne: Social change and cultural continuity among Native Nations . Rowman Altamira, 2006, ISBN 0-7591-1001-8 , 10: Toward a Multidimensional Historical-Comparative Methodology: Context, Process and Casuality, p. 200-220 (English).

- ^ Francis Paul Prucha: American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly . University of California Press, 1997, ISBN 0-520-20895-1 , Instruments of Federal Policy, pp. 100-102 (English).

- ↑ Michigan State University: "Transcription of the US Government: The Indian Removal Act of 1830 ( Memento of the original from May 26, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. "(English) Retrieved March 11, 2009

- ↑ Jeffrey D. Schultz, Kerry L. Haynie, Andrew L. Aoki: Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Hispanic Americans and Native Americans . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, ISBN 1-57356-149-5 , pp. 637 (English).

- ↑ A compilation of the most important documents in connection with the Indian Removal Act is available from the Library of Congress: Primary Documents in American History - Indian Removal Act . Retrieved March 11, 2009

- ^ Duane Champagne: The Choctaw People resist the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek . In: Marcia Haag, Henry Willis (Eds.): Choctaw Language and Culture: Chahta Anumpa . University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8061-3339-2 , Sp. 280-287 (English).

- ^ Text of the decision in the central Cherokee Nation v. Georgia: Cherokee Nation v Georgia, 30 US 1 (1831) ( Memento of the original from January 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English) Retrieved March 11, 2009

- ↑ 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. (No longer available online.) Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, archived from the original on May 4, 2007 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 (Dancing Rabbit Creek contract transcription). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ronald N. Sentence: American Indian policy in the Jacksonian era . University of Oklahoma Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8061-3432-1 , pp. 68--70 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e James Carson: The Choctaw Trail of Tears . In: Marcia Haag, Henry Willis (Eds.): Choctaw Language and Culture: Chahta Anumpa . University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8032-6902-1 , pp. 288-291 (English).

- ↑ James Carson: The Life in Mississippi after the Removal . In: Marcia Haag, Henry Willis (Eds.): Choctaw Language and Culture: Chahta Anumpa . University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, pp. 292-295 (English).

- ^ John Reed Swanton: Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians: The Journey of an Americal Congressman . University of Alabama Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8173-1109-2 , pp. 5 (English).

- ^ Valerie Lambert: Choctaw Nation: A Story of American Indian Resurgence . University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8032-1105-8 , pp. 40-41 (English).

- ↑ Muskogee Indian Tribe. (No longer available online.) In: Indian Tribal Records. Access Genealogy, archived from the original on March 17, 2009 ; accessed on March 29, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Charles J. Kappler. Washington: United States Government Printing Office , 1904 .: TREATY WITH THE CREEKS, 1825. In: Electronic Publishing Center Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University, accessed March 19, 2009 (transcribed from the original text of the Indian Springs Treaty).

- ^ Michael D. Green: The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis . University of Nebraska Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8032-7015-1 , Creek Removal from Georgia, 1826-27, pp. 126-140 (English).

- ^ Michael D. Green: The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis . University of Nebraska Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8032-7015-1 , The Abrogation of the Treaty of Indian Springs, 1825-26, pp. 98-125 (English).

- ^ Grant Foreman: Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians . University of Oklahoma Press, 1974, ISBN 0-8061-1172-0 , Chapter 11, The Creek "War" of 1836, pp. 140-151 (English).

- ^ Angie Debo: The Road to Disappearance: A History of the Creek Indians . University of Oklahoma Press, 1979, ISBN 0-8061-1532-7 , pp. 95-96 (English).

- ↑ Quotation: “Many… died on the road from exhaustion, and the maladies engendered by their treatment; and their relations and friends could do nothing more for them than cover them with boughs and bushes to keep off the vultures, which followed their route by thousands ... for their drivers would not give them time to dig a grave and bury their dead. The wolves, which also followed at no great distance, soon goal away so frail a covering, and scattered the bones in all directions. " Sylvia Flowers: Muscogee (Creek) Removal. In: Ocmulgee National Monument. National Park Service, accessed March 20, 2009 .

- ↑ Sylvia Flowers: Muscogee (Creek) Removal. In: Ocmulgee National Monument. National Park Service, accessed March 20, 2009 .

- ^ History of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians. (No longer available online.) In: Poarch Band of Creek Indians. Poarch Band of Creek Indians, archived from the original on July 27, 2010 ; accessed on March 20, 2009 (English, brief historical outline of the history of its origins and recognition). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A Chronicle, 1830-1849 - Arkansas Gazette, January 17, 1838. (No longer available online.) In: Sequoyah Research Center - American Native Press Archives. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, archived from the original August 10, 2009 ; accessed on March 20, 2009 (English, transcription of the original text of the report). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Russell Thornton: American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 . University of Oklahoma Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8061-2220-X , 5th Decline to Nadir: 1800 to 1900, pp. 113-114 (English).

- ^ Thomas Dionysius Clark, John DW Guice: The Old Southwest, 1795-1830: Frontiers in Conflict . University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8061-2836-4 , 12: Eclipsing Ancient Nations, pp. 250 (English).

- ^ Charles J. Kappler. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904: TREATY WITH THE CHICKASAW, 1818. In: Electronic Publishing Center Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University, accessed March 24, 2009 (transcribed from the original text of the Old Town Treaty).

- ^ Charles J. Kappler. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904: TREATY WITH THE CHICKASAW, 1830. In: Electronic Publishing Center Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University, accessed March 24, 2009 (transcribed from the original text of the Franklin Treaty).

- ^ Duane Champagne: Social order and political change: constitutional governments among the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Creek . Stanford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-8047-1995-0 , The Removal Crisis, pp. 146-164 (English).

- ^ A b c Arrell Morgan Gibson: The Chickasaws . University of Oklahoma Press, 1971, ISBN 0-8061-1042-2 , Liquidating the Chickasaw Estate, pp. 169-178 (English).

- ^ Charles J. Kappler. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904: TREATY WITH THE CHICKASAW, 1832. In: Electronic Publishing Center Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University, accessed March 24, 2009 (transcribed from the original text of the Pontotoc Treaty).

- ^ Charles J. Kappler. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904: TREATY WITH THE CHICKASAW, 1834. In: Electronic Publishing Center Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University, accessed March 24, 2009 (transcribed from the original text of the Treaty of Washington, 1834).