Spanish colonial empire

The Spanish colonial empire ( Spanish : Imperio español ) extended across America , Africa , Asia and Oceania , with a territorial focus in America. At the zenith of its power, the Spanish colonial power was one of the greatest empires in human history and also one of the first global empires. It existed from the 15th century to the second half of the 20th century.

Beginnings

As the beginning of Spanish colonialism, the systematic conquests of the Crown of Aragon in the Mediterranean area in the 13th and 14th centuries can be set, including Naples , Sicily , Sardinia and even areas in today's Greece. Frequent conflicts with the expanding Ottoman Empire (see: Duchy of Neopatria ) and the Italian maritime republics of Genoa and Pisa together (see: Corsica ), which disputed many areas and colonies in Aragon, were the result. It was not until the beginning of the 15th century that Castile began to show increasing interest in expeditions to the west. Another reason was the rivalry with the Kingdom of Portugal , which had achieved supremacy in maritime trade. To get to the goods of the Orient to arrive whose trade routes (especially to the spices of the Pacific Islands), the Ottomans or the Italians locked firmly in hand, had competed in Spain and Portugal together to instead of the traditional country lane through the Middle East a to find a new route. The Portuguese, who had completed their Reconquista long before the Spanish, began their expeditions with the aim of first gaining access to raw materials from Africa and then bypassing Africa, which would give them control over the islands and coasts of this continent. In doing so, they opened a new shipping route to the East Indies, were no longer dependent on trade through the Ottoman Empire, which was a monopoly of Genoa and Venice , and thus laid the foundation for the Portuguese Empire. Later, when Castile had completed its Reconquista, the Catholic Kings supported Christopher Columbus . Obviously convinced that the earth's circumference was smaller than the real one, he wanted to get to Cipango ( Japan ), China , India and the Orient by sailing west, with the same purpose as the Portuguese: away from Italian cities independent to get goods of the Orient, especially spices and silk (which were finer than what had been produced in the Kingdom of Murcia since the rule of the Arabs). It can be assumed that Columbus would never have achieved his goal; but halfway was the American continent and, without knowing it, he “discovered” America and thus initiated the colonization of the continent by Spain.

Conquest of the colonial empire

Origins

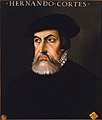

After the discovery of America in 1492 (after the actual discovery around 10,000 BC by the Northeast Asian peoples and around 1000 by the Vikings ) by the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus in the service of the Castilian crown, the conquista (Spanish: conquest ) of the double continent began. Numerous Spanish adventurers and adventurers, most of whom came from Extremadura or were veterans of the Reconquista , flocked to the New World in order to quickly attain fame and fortune. Extremadura at that time was a barren, desolate and impoverished Spanish province; While the first-born usually inherited the father's land, the second- or third-born could only earn their living as soldiers, which is why many of them took part in the Reconquista. After the fall of Granada in 1492 and the associated end of the Reconquista, however, they lost their livelihood. So it is not surprising that the two most important conquistadors Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro also came from this province. Already in the surrender of Santa Fe , which Columbus concluded with Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon , the main features of the Conquista of America are already recognizable.

As can be seen from the treaty, it was the aim of the Castilian crown to discover new countries and to conquer and exploit them in order to achieve a world power status that Portugal held at the time . This also shows the later practice of the Capitulación , in which a conquistador was obliged in a contract with the king to take possession of the military in the name of the crown, to settle the newly founded colonies and to proselytize the indigenous population to Catholicism at his own expense take over against the assurance of various financial advantages such as B. the ( Quinto real ) of the precious metals found. The Capitulación was thus a kind of royal license to a private entrepreneur. After a successful conquest, the applicants were usually given the title of governor or captain general . For example, Cortes was appointed governor general after the conquest of Mexico and Pizarro became captain general after the conquest of Peru . After signing the Capitulación, the entrepreneur was responsible for equipping his expedition and recruiting seafarers, priests / monks and soldiers. Conquistadors were usually not royal soldiers or mercenaries who received a fixed wage or salary, but volunteers who went into debt to buy their equipment. Their interest was directed to get the maximum profit from the expedition, because this was the only way to pay off the debts.

The result of this policy of conquering Castile was the encomienda system, which was introduced by Isabella I in 1503. The conquistadors were given very large estates together with the indigenous population living there, but the lord of the indigenous population was formally the crown of Castile. She commissioned the contractor to take care of the protection and proselytization of the Indians living there . In practice, however, the Indians were enslaved . The Dominican Antonio de Montesinos drew attention to the bad treatment of the Indians in his Advent sermon from 1511 . This sparked for the first time a debate about the living conditions of the Indians among the Spanish conquerors. As a result of this debate, the Leyes de Burgos were passed in 1513 , laws in which any use of force by the Encomenderos against the Indians was expressly forbidden. However, very little changed in practice, because the Spanish crown simply lacked a control body in the New World. The in many cases inadequate implementation of the laws led to numerous protests and demands, because in reality the laws were only viewed as a legalization of the already dreary situation. It was not until the Dominican Bartolomé de Las Casas , who denounced the conditions of the indigenous population in Spain , that the Leyes Nuevas (New Laws) came about in 1542 , in which the Indians were finally placed under the direct protection of the crown. However, these were only implemented slowly and partially withdrawn as early as 1545. So the encomienda system was de facto continued until 1549. With the creation of the so-called Repartimiento system one wanted to achieve a more effective protection of the Indians. From now on they lived in communities and committed themselves to providing men from their own ranks as labor for temporary projects on the part of the state. The size of this work force was two to four percent of the male population. The division was supervised by the (regional) governor or the Corregidor or Alcalde Mayor , who was also responsible for protecting the indigenous population and had to point out any grievances.

Carrying out the Conquista

The main goal of the conquistadors was not the development of new areas and their settlement, but the search for gold and other riches, for which the myth of the legendary gold country El Dorado was of decisive importance. In doing so, they were mostly ruthless and brutal towards the indigenous population.

Through the Requerimiento , the conquistadors were granted a license by the Castilian monarchy, in which the Indians of Central and South America were asked to submit to the rule of the Castilian crown. Since the document was only read in Spanish, most of the Indians did not understand its meaning and therefore refused. So they were eventually declared outlawed and murdered.

Through targeted destruction, Hernán Cortés , among others, succeeded in conquering the empire of the Aztecs and Francisco Pizarro the great empire of the Inca and finally founding the viceroyalty of New Spain and Peru on their ruins.

The founding of cities was crucial to the success of the Spanish in the New World. They were safe retreats both from hostile Indians and from other European powers, especially Portugal and England , who contested Castile territories on the Río de la Plata ( Colónia do Sacramento ) and North America ( Nootka Territory ). Cities were also centers of administration, education, and intra-American trade.

The Castilian Crown gave precise instructions on how and by what means a city was to be founded. The aim was to avoid the situation that occurred at the beginning of the colonization of the island of Hispaniola , when many Spanish settlements ( La Navidad , La Isabela ) had to be abandoned after a short time or were destroyed by Indians. It was not until 1498 that the first permanent settlement was established with Santo Domingo , which was then the seat of the viceroy or the governor until the conquest of Mexico. Through targeted selection, cities were initially only founded in sparsely populated remote areas, such as California or Nevada . Attempts were also made to conquer existing cities and centers of the Indians. Cortes finally succeeded in 1521 in taking Tenochtitlan , the capital of the Aztec Empire, on the ruins of which Mexico City was founded, the new capital of the viceroyalty of New Spain. The Spaniards systematically destroyed every visible memory of the ancient culture and built their churches and palaces in the style of the Renaissance where the great temples and rulers' domiciles stood . Finally, the Lago de Texcoco , the lake from which Tenochtitlán was surrounded, was drained so that the city could continue to grow.

The Conquistadors did the same in the Inca Empire. Cuzco , the capital of the Inca Empire, was completely destroyed and lost its capital function to Lima, which was founded in 1535 by Pizarro on the Peruvian coast . The city initially housed only a dozen conquistadors and the roofs were made of reed. In 1542 the Spaniards founded the viceroyalty of Peru with Lima as the capital. In the 16th century, more than 40 cities were founded in Spanish America, all of which, with the exception of Mexico City and Cuzco, were newly founded for geopolitical and economic considerations. Many of these cities were named after well-known cities in Spain ( e.g. Santa Fe , Córdoba , Guadalupe , Granada ) or because of the religiosity of the Spaniards after saints (e.g. San Francisco , Santa Maria , San Antonio ) or holy objects (e.g. B. Vera Cruz , Sacramento ). The local characteristics also played a role, for example Las Vegas got its name from the floodplains found there. In some cases, however, the indigenous name was retained, as in the case of the already mentioned Cuzco or Manila in the Philippines, which formed the capital of Spanish East India .

Due to the enormous administrative apparatus, well-trained colonial officials were required. Universities were therefore established in the New World very early on. The first Spanish university on American soil was founded in Santo Domingo in 1538, followed by Mexico City and Lima in 1551. As a result of this development, many cities became centers of education.

Colonial administration under the Trastámaras and Habsburgs

The viceroys system

After the first phase of the Conquista, the Castilian crown set up administrative units in the former great empires of the Aztecs and Incas. The existing economic and cultural centers were often retained. That was after the destruction of Tenochtitlan from the remnants City Mexico was founded, which eventually became the capital of New Spain. Since the system of viceroys had been introduced in the countries of the Crown Aragon since the Middle Ages , this was now transferred to the New World, even though Aragon was excluded from colonization. In 1535 the viceroyalty of New Spain and 1544 the viceroyalty of New Castile , which was later renamed Peru, was founded.

For the viceroy, the crown did not - in contrast to the lower administrative levels - provide any special powers in the administrative, military and jurisdiction areas. Rather, the viceroy had the task of representing the Spanish-Castilian monarchy in the New World and was thus a general political authority who made a decision in disputed cases in which the normal administrative authorities failed. In the early phase of the viceroyalty, the title was in principle not an office, but only a special power of attorney delegated to the viceroy by the Spanish-Castilian monarch. The viceroy exercised the supreme power of government ( Gobierno Superior ) on behalf of the monarch . He was responsible for the supervision of the judiciary, the well-being of the subjects, the maintenance of security and order, spreading the Catholic faith, protecting and integrating the Indians and rewarding conquistadors and their descendants. Because of these "monarchical" tasks, the viceroy had to hold his own court and perform a special ceremony similar to that of the king in the motherland. He was also assigned his own bodyguard, which was only under his command. All of these royal properties were intended to symbolize the solidarity of the king with his subjects in the colonies and thus bind them to the Castilian crown.

Furthermore, in his capacity as deputy king, the viceroy could also issue orders to the other colonial officials, but he was not permitted to intervene in official powers or even to curtail competencies. Since the viceroys were both governors and presidents of the Real Audiencia in the capitals and at the same time held the office of captain general , they also had administrative, judicial and military tasks within a limited geographical framework. In contrast to the other royal colonial officials, a viceroy always had to hold these three additional offices. One reason for this was that it strengthened the viceroy's political power and thus ensured that he was the only one at the head of the Spanish-Castilian colonial administration.

Inner and outer structure of the viceroyalty

Real Audiencias

At the beginning of the 16th century the judiciary and royal jurisdiction were still handled in the Castilian motherland (Audiencia of Valladolid / Granada), due to the distance and the lack of legal institutions in the New World, a Real Audiencia , i.e. a royal court of appeal, was decided in 1511 Establish Santo Domingo on Hispaniola . The aim of this new institution was of course to limit the power of the Viceroy and Governor of the West Indies, Diego Columbus , Christopher Columbus' son, as much as possible.

This facility also represents the first attempt to organize the conquered areas politically and administratively, which was particularly difficult in the initial phase in the Caribbean, as the Crown initially underestimated the scope of the discoveries and therefore no management concepts were developed .

Christopher Columbus was granted the title of governor and viceroy in the Capitulaciones de Santa Fe, but without any actual political power and authority. The lack of separate areas of responsibility led to numerous uprisings by the colonialists and created an unmanageable mess and arbitrary rule. Columbus' successor Francisco de Bobadilla , who was appointed governor from 1499, did not succeed in pacifying the region and installing an efficient administration. Only Nicolás de Ovando was able to achieve a reasonably stable administration through the consistent application of the encomienda system. The administration was later transferred back to the Columbus family, so that finally Diego Columbus was reinstated as viceroy and governor, albeit with the restriction to the islands and areas that only his father had discovered. In the following years Diego was recalled and the government responsibility was transferred directly to the Real Audiencia and finally even to the monastic order of the Hieronymites.

With the creation of a Real Audiencia, the aim was to put a stop to this confusion of the different demands and administrative levels and make the administration exclusively dependent on the crown.

After the conquest of Mexico had progressed further, it was decided in 1527 to set up another audiencia in Mexico City in order to create clear conditions immediately after the conquest and to avoid a repetition of the "Caribbean difficulties". In contrast to the one in Santo Domingo, the Real Audiencia of Mexico was also responsible for matters of last resort and was therefore entitled to use the royal seal. Here, too, they wanted to restrict the powers of the conquistador Hernando Cortes as captain general and governor of New Spain. This practice later became a practice with the creation of new audiencias that curtailed the powers and legal positions of the conquistadors and other deserving individuals in order to prevent a dangerous concentration of power in one person's hands. As a result, more audiencias were founded, in 1542 Guatemala , 1548 Guadalajara and finally, in 1583 , a separate audiencia was set up in Manila in the Philippines , which also belonged to the viceroyalty of New Spain . Before the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Castile in 1542, later the Viceroyalty of Peru , the Audiencia was founded in Panama in 1535 , Lima was added in 1542, Bogotá in 1548 , Charcas in 1559 , Quito in 1563 and Chile in 1603 . Initially, not all audiencias received the same rights and privileges, but under Philip II, all audiencias in the New World and the Philippines were given the status of a chancillería . They were thus entitled to wear the royal seal and to issue powers and ordinances in the name of the king. This was important insofar as the judges and judicial officers were also responsible for the control and supervision of the governors and captains general, or in the event of illness or death they could temporarily take over the civil and military administration of the colonies themselves. The Audiencias became the actual colonial authorities and thus the centers of administration in the New World, which enabled a comprehensive administrative system that followed a strictly bureaucratic model and made intervention by the Crown possible at any time.

In the capitals of the two viceroys, Mexico City and Lima, the viceroy also exercised the office of President of the Audiencia, which created a further control factor, since the viceroys could only be appointed by the crown itself.

Provincial, regional and local administration

The division of the provincial, regional and local administration was not clearly defined. So many areas overlapped. Different definitions of administrative units and divisions can be found in the specialist literature. An established structure is as follows: The audiencias were subdivided as presidencias (to differentiate between the purely administrative and legal powers of the audiencias) into so-called gobiernos ( governorates ), which in turn were subdivided into corregimientos and Alcaldías Mayores . In addition, there were the general captains and ecclesiastical administrative units such as (arch) dioceses and religious provinces.

Gobiernos

The individual governors or gobernadores had different administrative positions and hierarchies. Fortress commanders as well as heads of urban parishes and heads of entire provinces were also named governors. The governors had powers in the judicial, military and financial sectors. Originally, the governor was the head of a province who concentrated exclusively on civil administration and was therefore only supposed to implement the instructions of the king or monitor their execution. He had to look after the common good in the province by passing laws and regulations for the public transport, the economy and the provincial authorities.

The governor also had the authority to exercise a control function in the financial sector, but not the right to generate tax revenue independently, but should only assist the royal tax officer in his duties. Later, the competences in the area of jurisdiction were firmly linked with the office of governor in his capacity as Justicias Mayores (chief judicial officer). He was responsible for the judiciary in the first instance, in some cases also in the second instance, as well as the control of the other judicial officers in the local and regional administration. The governors were subordinate to the king in the civil administration area, but to the president of the Audiencia or the viceroy in the capital cities in the area of justice.

The military powers of the governor related to the command of the troops and militia units and their supply, but they were subordinate to the competent captain general, who was primarily the viceroy. In some cases, such as in the Philippines or Chile, the governors themselves exercised the function of captain-general because of the huge distances, as this was the only way to ensure a quick defense of the colonies. Due to these different functions, it happened that a governor had to visit several superiors, usually spatially separated from one another. For example, the governor of Santiago de Cuba was militarily subordinate to the captain general of Havana , while in his function as Justicia Mayor the president of the Audiencia in Santo Domingo on Hispaniola.

Corregimientos and Alcaldías Mayores

With the establishment of the Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1535, the regional and local administration began to set up so-called corregimientos in the Indian communities based on the model of the Castilian municipal administration , which should end or restrict the rule of the encomenderos over the Indians, which was also partially successful . A distinction was made between the Corregidores de Indios , who presided over the Indian communities, and the Corregidores de Españoles , to which the Spanish cities were assigned (see city administration below).

The corregidor was now the highest colonial official in the individual communities and cities. In addition, there was also the office of Alcalde Mayor , which had only been introduced in New Spain and had similar powers and competencies. Initially, the plan was to replace all Corregidores and replace them with Alcaldes Mayores . These should be lawyers and head a district formed from several Indian communities, in which they would have to exercise jurisdiction and police power. With this dissolution of the Corregimientos one would have lost the direct control over the Indian municiples, so that one decided to keep them with the simultaneous introduction of the Alcaldes Mayores . Thus, between 1550 and 1570, 40 Provincias Menores ("subordinate provinces") were set up, each headed by an Alcalde Mayor and made up of several Corregimientos . In contrast to Peru, New Spain succeeded in building up an effective district administration in which the competencies between local and regional administration were clearly separated. Due to the rapid population decline of the Indians, however, many previously established corregimientos were not reoccupied because the crown was no longer able to adequately pay all officials due to the associated loss of tribute payments. So one went over to connecting most of the Corregimientos to the Alcaldes Mayores . This mixing of offices blurred the difference between local and regional administration, and a clear separation was no longer possible in the period that followed. The Alcalde Mayor now acted like the Corregidores as a kind of district governor of the lowest administrative level, who had largely the same functions as the previously created Corregidores de Indios . Already in the 17th century there was hardly any distinction between the two offices and the same district was sometimes referred to as Corregimiento times Alcaldía Mayor . The principle of only looking after lawyers with these tasks has also been abandoned. The authority to appoint officials passed to the crown in the second half of the 17th century.

Most of the various Alcaldes Mayores and Corregidores also had military functions. They had a say in the appointment of Capitán de Guerra (war captain ) and Teniente de Capitán General (vice-general captain ) or were raised to these offices themselves. However, these offices only played a subordinate role and mostly only came into play during Indian riots, for example when militia troops were to be set up. The individual appointments were, however, always retained, since the civil servants had the right to levy additional taxes due to the "extra work" of their activities and they did not want to forego this lucrative additional income.

Due to the meager wages they received from the Crown, all officials were dependent on additional income, as otherwise they could not maintain the standard of living corresponding to their class. Corruption , abuse of office and debt deals were the order of the day. The most common additional source of income was trading with the residents of the individual districts. They bought regional products in advance through city wholesalers or sold city goods on credit. Due to their state authority, they succeeded in developing monopolies and abusing them. Although the crown forbade this type of “fundraising”, it also sold the offices and also set the purchase price of the office in relation to its income. The consequence of this ambiguity was that the offices in the districts became commercial properties, which were judged solely on the basis of earnings opportunities. As a result of these conditions, the entire district administration was actually inefficient and unable to integrate the Indians into the colonial administration, since the responsible officials primarily pursued personal interests.

Administration of the cities

The administration of the newly founded cities followed the Castilian model. A city council, known as the Cabildo , was set up in each city, made up of councilors, the regidores . The composition of this “city council” was decided either by election, by drawing lots or on the proposal of the governor. Since the second half of the 16th century, the Cabildo was solely responsible for municipal administration. The composition depended on the size and status of the cities. The smaller towns with the town charter of a villa had only six regidores , while the larger towns with the title of a Ciudad had twice as many.

The honorary office of the regidor already became a purchasable title under Philip II , which was sold to the highest bidder and could either be resold or inherited by the buyer. In addition to council business, the regidores also had other fixed offices, such as that of Alférz Real , the royal standard- bearer who was authorized to carry the flag at public celebrations. As Alguacil Mayor , a Regidor was responsible for the city prisons and also exercised police power.

All questions relating to the city were decided by majority vote, as well as the occupation of the municipal offices and the salaries of the other city officials. The chairmanship of the Cabildo was held by the Corregidor de Españoles or the Alcalde Mayor or, in special cases, the governor, if the respective city was its official seat. These royal officials did not have the right to vote in the council, but they were able to influence the resolutions considerably through a right of proposal and veto. This was particularly evident in the election of the various municipal office holders, who had to be duly confirmed before one of the elected persons could take office.

There were also two city judges elected for one year, the Alcaldes Ordinarios , who did not need to be a member of the magistrate and who, like the royal officials, exercised jurisdiction in the first instance. The urban population could therefore choose between several dishes. The first of the two city judges also had the right to represent the governor or the Corregidor / Alcalde Mayor , not only in the function of the royal official, but also through the government of the entire province / district, if none in this area Audiencia existed. The other city offices, which often depended on the level of development of the individual cities, included the Mayordomo , a kind of financial city councilor, who was responsible for the tax regulation and financial administration, or the Procurador General , who took on the duties of a city council lawyer and in disputes for the "legal General Welfare “had to worry about the city. The entire correspondence between the crown and the city as well as the other colonial authorities was also his responsibility. Another very respected office was that of town clerk or notary. This city official, known as Escribano de Cabildo , was the recorder of the council meetings and head of the city archives. The city's economic affairs were handled by the Fiel Ejecutor . He was responsible for supplying the cities with food, which was especially important for the poorer urban population, and was also responsible for commercial jurisdiction and the establishment of uniform measurements and weights.

As all of these offices could be bought, the cities deteriorated at the beginning of the 18th century, as the city council was more interested in collecting prestigious offices than in the city's well-being. In the course of enlightened absolutism , the crown tried to make the city administration more efficient again. The city finances were subordinated directly to the crown by creating a separate financial authority in the capitals of the viceroyalty, which was supposed to supervise the city finances in general and created a separate financial plan for each city. Through the appointment of so-called honorary councilors, the Regidores Honorarios , and a special lawyer who should represent the interests of the population, the aim was to restore confidence in the city administration. However, since all offices were still determined by the Cabildo , very little changed in practice. Only with the Bourbon reforms did reurbanization succeed.

General captans

To secure Spanish rule, military districts, the so-called Capitanías Generales (general captains) were installed in the two viceroyalty. As a rule, the viceroy was also captain general. Only in some militarily problematic provinces, such as Chile or the Philippines, was the office of governor combined with that of captain-general in order to be able to guarantee efficient intervention, because due to the great distances it often took days and weeks for couriers to obtain approval and brought orders from the viceroy.

With the office of the captain general, however, not only the supreme command of the troops in the captain's office was connected, but also the entire supply and equipment system as well as the military jurisdiction. In the event of military threats from foreign powers or other armed conflicts, the captain general had to take all necessary measures in his district to protect and defend the colonies. To do this, however, he had to coordinate with the other colonial authorities at the same hierarchical level, so that in the event of a state of war, a junta de guerra (council of war) was usually convened. All necessary measures could then be coordinated here.

In the military jurisdiction, the captain general had to appoint a so-called Auditor de Guerra , whom he had to follow in reaching a judgment, this was either a member of the Audiencia, if the captain general was also president of one, or a lawyer of his choice.

Colonial authorities in the mother country

Casa de Contratación

The Casa de Contratación was a kind of chamber of commerce that was founded in Seville in 1503 at the instigation of the Archbishop of Burgos, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca . The Chamber approved trips to the New World, was responsible for the organization of the fleet, as well as its movements and administration, and received the income from trade with the viceroyalty. In addition, she also took on the function of an immigration and customs authority. All ships and people arriving in Spain from the New World fell under their jurisdiction. Likewise the criminal matters in the tax and commercial sector. The emigration to America was regulated by this institution, in that only those persons were allowed to emigrate who had the "purity of blood", i.e. were not Jews, Muslims or Converso. In the beginning, subjects of the lands of the Crown of Aragon were also excluded.

As the Spanish counterpart to the Portuguese “ Casa da Índia ”, it was also a navigation center where knowledge about new travel routes was gathered. In this capacity, the Casa de Contratación appointed a "piloto mayor", a kind of supreme naval commissioner, whose task was to collect nautical information about the West Indies and America.

Consejo de Indias

In parallel to the Casa de Contratación, the “ Consejo de Castilla ”, the Castilian Privy Council, developed a commission chaired by the Archbishop of Burgos, which dealt exclusively with American issues. As early as 1516 with the death of King Ferdinand II of Aragón, it was given the name " Consejo de Indias ", ie Council of India, as it was initially assumed that Columbus had discovered India. Despite the later realization that this was a new continent, the name was retained. It was not until 1523 that the Council of India was spun off from the Privy Council and established as a separate authority with extensive powers. From then on, both the Casa de Contratación and all Spanish colonies in the New World and Asia were subordinate to this. He was also responsible for supreme jurisdiction in all criminal and administrative matters in Spanish America and Asia. He also took on legislative and executive functions within the Spanish monarchy. In 1595 the council was expanded to include the "Junta de Hacienda de Indias", which dealt with all economic issues. Finally it was decided to entrust the military defense of the colonies to a separate council, the "Junta de Guerra de Indias" founded in 1597.

The Council of India consisted of a President, about twelve councilors and an orderly staff. The offices included a grand chancellor, a treasurer, two secretaries, a clerk, a cosmographer, a chronicler and a lawyer for the poor. Its members were predominantly lawyers, theologians or other scholars, mostly of bourgeois origin, and without exception were appointed by the crown. The resolutions reached through joint meetings were submitted to the king in a "consulta", a kind of expert opinion. If the king confirmed the report, the council drafted a legal text, which was then referred to as the "real cédula" (royal decree). This was the standard practice for legal orders. In addition, there was also the “real provisión”, a type of law that was only solemnly proclaimed by the “Cortes” (Castilian assembly of estates) and equated with their resolutions. The royal letters ("cartas reales"), which were also legally binding, should also be mentioned. With these letters, the king often made decisions about official matters in the colonies directly without the Council of India.

Due to this confusing flood of laws and letters, their execution became increasingly problematic, so that one began to draft law books from the individual documents. These should then have been valid in the entire colonies, but it was not until 1596 that the “Cedulario Indiano” was published as a comprehensive text with 3500 laws, which was used as a standard legal work until the Bourbon reforms.

Colonial administration under the Bourbons

In the course of the Spanish War of Succession , in which the Habsburg-French antagonism came to light again, the French ruling dynasty of the Bourbons succeeded in conquering the Spanish throne. The change of dynasty did not trigger any particular protests in the Spanish colonies, but was largely accepted as such, since it was initially assumed that the Bourbons would retain the Habsburg administrative system. At first it also seemed as if the new Bourbon king Philip V was paying little attention to the colonies in the New World and was concentrating more on the Spanish motherland. First reforms changed the Habsburg authorities and civil servants from the ground up and thus enabled a tight administration of the provinces in the motherland.

This new concept, later referred to as the intendant system, was then under Charles III. gradually transferred to the colonies in the New World as well. Naturally, this led to conflicts with the established colonial officials, as this new system endangered their power. These new concepts were necessary from the point of view of the Bourbons, because the Spanish colonial system had increasingly stagnant characteristics from the end of the 17th century and was increasingly inefficient and sluggish, which led to the loss of territory in the Caribbean and South America to the aspiring English and French and Dutch led. Until the accession of Charles III. In Madrid , however, they limited themselves to the enactment of new laws and framework conditions which were intended to combat the acquisition of offices and the rampant corruption, which was only remotely successful.

The prohibition of the encomienda system, which was still used in some areas despite the introduction of the repartimiento, was also important in this early phase of the Bourbon reform projects . This measure, too, was hardly taken into account in the colonies, as it would in turn have endangered the influence of certain groups of people, so that it ultimately remained largely with the impermeable Habsburg system.

The real wave of reforms only started with Charles III. one who, together with his “India Minister” José de Gálvez y Gallardo , wanted to fundamentally change the colonial administrative structures in Spanish America.

Division of the Viceroyalty of Peru

Due to its size, the Viceroyalty of Peru proved increasingly inefficient and increasingly economically stagnant. From a military point of view, too, it could hardly oppose the English, French and Dutch who had established themselves in the Caribbean and in the north-east of South America. The Caribbean had become a hub of international trade and thus to an outbreak of internationally active since the 16th century piracy developed.

Viceroyalty of New Granada

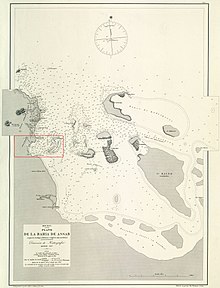

For the first time in 1717 and finally in 1739, a new administrative-political unit was created, the so-called viceroyalty of New Granada with Bogotá as the capital. This new political-administrative unit was supposed to ensure the security of the Caribbean trade routes and defend the traditional colonial possessions against foreign powers as well as monitor the Isthmus of Panama .

Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

Significant military problems arose in southern Peru as the Portuguese tried to expand their zones of influence from Brazil . The main object of contention was the Colonia del Sacramento , which changed hands several times. In addition there was also the arbitrariness of the Jesuit reductions located there , which gradually formed a state within a state.

In 1776 it was finally decided to further downsize the viceroyalty of Peru by installing a fourth viceroyalty in the south, the so-called viceroyalty Río de la Plata . This new administrative unit was not only created for military reasons because of the Portuguese advancing west and the presence of the British in the South Atlantic, but it was also linked to an economic reorganization in Upper Peru and in the area of the Río de la Plata. From now on, silver exports were no longer handled via Lima, but from Upper Peru via Buenos Aires . This meant a major loss for Lima's merchants and drove the once rich Peru to the edge of Spanish America.

Administrative reforms

With the accession of Charles III. the regional and local administration took new paths to fundamentally reform the confusing and thus inefficient Habsburg administration with the so-called intendant system. A clear centralization towards the Spanish motherland can be seen. As a first step, Charles decreed the redistribution of the provinces into the viceroyalty, whereby the Gobiernos were retained on the border areas for military reasons. Río de la Plata started in 1782, followed by Peru in 1784 and New Spain in 1786. New Granada and the Real Audiencia de Quito were excluded from the reform.

Each of these provinces, now called Intendencias (Intendanturen), was headed by an authorized representative (Intendant) appointed directly by the King. In contrast to the previous office of (provincial) governor, who only held the civil-political leadership, the director was now responsible for the entire provincial financial administration. Every year he had to make a visit to his province in order to promote the development of the country and to put an end to possible abuses. The jurisdiction was also reorganized, so the director, unlike the governor, was no longer authorized to pronounce justice. For this task, the crown appointed a "deputy" of the director, who as Asesore Letrados ( Assessor ) now took over the jurisdiction in the provinces and who the director had to follow on legal issues. Furthermore, the office of artistic director was limited in time and paid with a relatively high salary, which should prevent the spreading abuse of office.

At the same time, the district and city administration was reformed. The offices of Alcaldes Mayores and Corregidores were abolished and replaced by the so-called subdelegados , who were no longer appointed by the crown, but by the responsible (provincial) director. In the case of the subdelegados , too , jurisdiction was decoupled and local judges ( Alcaldes ) were assigned. In order to generate a sense of responsibility for the common good, subdelegados and Alcaldes should not be foreign colonial officials appointed by the crown, as was customary before, but should come from the local upper class and exercise their offices on a voluntary basis. In villages that, due to their size and the Indian population, did not have their own Alcaldes , the subdelegado exceptionally exercised jurisdiction. In all other administrations, he was a kind of acting head, who only had the responsibility for the financial administration and had to ensure the supply of the troops.

There were also many innovations within the framework of the highest colonial administration. The endeavors were made to considerably reduce the powers of the viceroys. Among other things, they were deprived of their military and financial administration, which was subordinated to the army and financial directors appointed by the crown. The administration was now divided into two independent business areas, one encompassing all matters of civil government and jurisdiction, the other dealing with military and financial administration as well as economic agents. Although the viceroy remained head of the viceroyalty, he always had to talk to the finance, army and superintendent (judiciary). Furthermore, he was forbidden to interfere in the affairs of the Intendencias .

As a result of these measures, the viceroys also lost their dual function as provincial and general governors. This should lead to the viceroys concentrating exclusively on political leadership and leaving the purely administrative, military and fiscal tasks to trained specialists.

Restructuring of the colonial authorities

In addition to the administrative reforms, the colonial authorities in Spain were also restructured. After over 200 years of existence, King Karl III. the Casa de Contratación abolished, as a single monopoly port or a monopoly authority in the course of the comercio libre was seen as a hindrance to the movement of goods and thus also to economic efficiency. The Consejo de Indias remained in existence as a colonial authority until 1834, apart from a small interruption during the Napoleonic Wars, but it clearly lost its reputation and importance. In 1714 his legislative and administrative tasks were outsourced and from 1717 more and more of his powers were transferred to the newly created “Secretaría de Marina e Indias” , which the Bourbons eventually expanded into the central colonial authority.

Failure of the reforms

With all these reforms, the crown wanted to build up a tightly organized administration in the course of enlightened absolutism , which, however, met with numerous opposition and was therefore only insufficiently implemented. The viceroys saw their power endangered by the new (super) directors and therefore refused any cooperation or were not prepared to forego competencies. The (provincial) directors also encountered fierce resistance from the local upper class during the reshaping of the district and local administration, as they were not prepared to take on new offices that did not result in any financial or other advantages, which, on the contrary, only connected with burdens were. It so happened that the reforms were gradually being rolled back, and people were forced to reintroduce the old system. In 1787 the powers of the newly created office of superintendent were transferred back to the viceroys. The (provincial) directors, in turn, developed into mere executive organs of the viceroys with no personal room for maneuver. In the district and city administration, the subdelegados gradually got the same functions as the previously abolished Alcaldes Mayores and Corregidores .

The crown's reform projects had failed on the most important points and thus only accelerated the process of breaking the cord between the Creole upper class and the Spanish motherland. The newly independent states on the borders of the viceroyalty or provinces were based on the Bourbon administrative system and largely integrated it into their own state structure.

Colonial economic policy

Habsburg economic policy

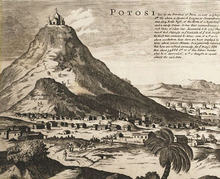

The Habsburg economic policy in the New World and Asia was aimed at providing the royal treasury with revenue for the purposes of European power politics. These included monopolies of the crown, such as the mountain or salt realm, which could be lent profitably to interested entrepreneurs. The production of finished goods such as wine , brandy and textiles was in turn reserved only for the mother country. Spanish America imported wine, brandy, textiles and metal goods, but also developed its own production and intensive intra-American trade. In the agricultural sector, the numerous haciendas supplied food for the major capitals of Mexico City and Lima as well as for the important mining centers of Zacatecas and Potosí .

However, silver mining was of decisive importance for the Spanish economic system . The mercury used to extract the silver in Potosí came from Europe and Peru. The crown's share of silver that was not used for administration flowed to Spain, plus income from leases and reals. The Spanish crown spent the silver mainly on war loans and flowed through it to the international financial centers in Genoa and the hostile Amsterdam . So much remained in Spain that the inflation rate of the European “ price revolution ” was higher the closer you got to Seville . It was therefore cheaper for the Spaniards and more profitable for the Dutch, French and other countries if the goods were not produced in Spain but imported there. This economic mechanism, together with the power-political overstrains, the population decline due to epidemics and the Spanish aristocratic mentality, ultimately led to an economic stagnation of the country, which is apparently privileged by its colonial wealth. However, the traded silver did not stay in the recipient countries, but was used to offset their passive trade balances with Eastern Europe on the one hand, and India and East Asia on the other. A world payment system emerged in which silver from America flowed in one direction with the annual Manila galleon across the Philippines and in the other direction via Europe to India and China , where the price of silver was highest.

Bourbon economic policy

After the Spanish Habsburgs died out , the Bourbons from France came to the Spanish throne. These carried out a comprehensive reform in the colonial economic policy, since the colonies, in contrast to the British and French, increasingly proved to be unprofitable. Furthermore, after the lost Seven Years' War, efforts were made to expand the military positions in the colonies and to secure the financing of imperial tasks. To this end, state revenues had to be increased.

Silver production was given new impetus by sending German mining engineers to Mexico and Peru. With the help of new institutions, the Tribunal de Minería (Mining Court) and the Banco de Rescate , which bought the silver from the mining companies at low prices, attempts were made to promote silver production.

The lucrative slave trade , which was meanwhile in French and British hands, was to come under Spanish management again.

The state monopolies for sugar, brandy and tobacco were not spared from the reform either. Growing areas for certain products and prices were determined. This met with fierce opposition. The wholesale merchants in Antigua and Guatemala City , for example, did not allow themselves to be ousted from the indigo business in Central America.

In 1765 the so-called “comercio libre” , a kind of free trade, was introduced, which contributed to a dynamization of the economy in the colonial empire. Some ports in Spain and Spanish America were given permission to trade with one another unhindered. In the American area, trade between Cuba , Puerto Rico , Santo Domingo , Margarita and Trinidad was now allowed, in Spain, in addition to the already established earlier monopoly ports of Seville and Cádiz (from 1717), Barcelona and Santander , the new one Scheme benefited significantly. In 1778 twelve ports in Spain and 24 in Spanish America were included in this system. The previously excluded areas of Venezuela and New Spain were added in 1789. Intra-American trade, which had been subject to strict restrictions in the previous centuries, was now able to develop increasingly between the individual provinces.

In the second half of the 18th century, the reforms gradually began to take effect and there was a marked increase in the exchange of goods between Spain and its colonies, both in volume and in value. Silver production increased significantly and gave a sigh of relief to the Treasury, which had got into difficulties due to high military spending. Through these reforms, the Spanish crown stabilized itself economically and was thus able to maintain its world power status into the 19th century.

Conflicts with Portugal

In 1494, in the Treaty of Tordesillas, the world was divided into a Castilian and a Portuguese sphere. Castile now received the right to all areas 1770 km (370 Spanish Leguas) west of the Cape Verde Islands , Portugal all east of it. Since there were renewed conflicts over ownership of the Spice Islands and the exact border with Brazil, the agreement was specified in 1529 by the Treaty of Saragossa , in which the demarcation line was moved to 1423 km (297.5 Spanish Leguas) east of the Spice Islands.

From 1580 to 1640 Portugal united with Spain in a personal union , so that the Portuguese colonies also fell to the Spanish crown for a time . The Treaty of Saragossa thus became irrelevant.

After the independence of Portugal, there were again conflicts between the two colonial powers, especially in South America the colony of Colonia del Sacramento (Uruguay) was a permanent object of contention. In the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) it was assigned to Spain and, after renewed disputes, Spain's rights were affirmed in the Treaty of Madrid (1750). However, this did not stop Portugal from reoccupying the area during the Seven Years War . In the Treaty of Paris (1763) Portugal then got sovereignty over the area. It was not until the Treaty of San Ildefonso (1777) that the colony finally came to Spain and was incorporated into the viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata . In the same treaty, Portugal ceded the islands of Fernando Póo and Annobón (Equatorial Guinea) to Spain.

Role of the Catholic Church

As early as 1478, during the Reconquista , Pope Sixtus IV granted the Catholic Kings Ferdinand II and Isabella I permission to set up a Spanish national inquisition that was independent of Rome . In 1488, a higher state authority for the Inquisition, the so-called Consejo de la Suprema y General Inquisición (called Suprema for short ) was installed. This council gave the Spanish Inquisition a state character. In 1501 the Catholic Church in Spain submitted to the patronage of kings for realpolitical reasons in order to secure secular support for its missionary goals. This solidified the function of religion as the legitimacy-creating principle of the Spanish monarchs, their expansion and, as a result, a complex connection between religion and rule.

In Hispanic America the Church fulfilled an educational and disciplinary task, the importance of which for Spanish rule should not be underestimated. It had an organizational structure that was quickly established, both at the level of the dioceses and parishes as well as the various monastic orders, which by far exceeded the royal administration in terms of density and personnel. Franciscans and Dominicans accompanied the Spaniards from the beginning of the Conquista and settled in America. In the course of time the Augustinian hermits and the Jesuits also came , who worked in Peru from 1568 and in New Spain from 1572 . The first American bishop reached Puerto Rico in 1512, and by the end of the century 31 dioceses had been established. In 1546 Santo Domingo , Mexico City and Lima , and in 1564 Bogotá were elevated to the status of a metropolitan seat. To monitor the orthodoxy of the non-Indian population, separate inquisition courts were established in Lima in 1570, in Mexico City in 1571 and in Cartagena in 1610.

The Indian mission ultimately reshaped indigenous cultures profoundly. The introduction of Christian morality to enforce monogamy changed the family structure significantly, which in turn led to a new social structure. A complete Hispanization was not aimed at. That was not possible due to the language differences. Abolishing the differences between Indians and Spaniards or Creoles would have endangered the social order. The Indians should keep their identity, but one wanted to socialize the different indigenous peoples according to their own ideas. Overall, they reacted to the Catholic proselytizing with considerable creativity. They selectively integrated new beliefs, values, rules, technologies and products into their cultures and forms of society, which - albeit radically changed - were able to ensure their survival.

In the course of the Bourbon reforms, the relationship between the Church and the Jesuits and the state also changed. In 1767 the crown finally expelled the Jesuits from Spain and Spanish America. The order was charged with inciting the Madrid hat revolt , in which the population, supported by parts of the nobility and clergy, demonstrated against the reform policy in 1766. The king retaliated for this humiliation by expelling all Jesuits and accusing them of wanting to form a state within a state in every respect . Not least the arbitrariness of the Jesuits in the area of the Rio de la Plata and the Paraná ( Jesuit reductions of the Guaraní ), where Spain was in a border dispute with Portugal and in which the Fathers pursued an independent policy, led to the conflict between the Society of Jesus and the Crown.

A total of 2,630 Jesuits had to leave Spanish America. This led to a further alienation of the Creoles from the mother country, since the elite of Spanish America had largely been educated and shaped by this order.

Decline of the colonial empire

Reasons for the decline of the Spanish empire were, in addition to the wars of independence sparked by the French Revolution and the Haitian Revolution, the colonial aspirations of England / Great Britain, France and the Netherlands, which succeeded in severely disrupting Spanish hegemony.

Loss of america

Red: Royalist reaction

Blue: Under the control of the separatists

Dark blue: Under the control of Greater Colombia

Dark blue (mother country): Spain during French invasions

Green: Spain during the liberal uprising

The Bourbon reforms led to rebellions and protests against the new policies of Madrid, especially in the American colonies. The Creole ruling class did not succeed in winning the broad masses for a revolution, so that the colonists initially remained loyal to the crown. Only when the crown showed weakness as a result of Napoleon's foreign and trade policy did the spark of independence struggle spread to Spanish America. This did not take place in a radical upheaval, but in small steps in many places and provinces. Due to the disputes between King Charles IV and his son Ferdinand VII , Napoleon was able to occupy Spain and raise his brother Joseph I to the Spanish throne. This change of power was followed with concern in the colonies and the local elites in the colonies continued to express their loyalty to the Bourbon royal family. A detachment from the Spanish motherland was not yet apparent. Spain no longer had a unified leadership because Joseph was exposed to fierce Spanish resistance. The central junta formed in Cadiz , which wanted to establish a constitutional monarchy, was only responsible for a small area, and Ferdinand VII did not send any political signals from exile either. This situation made the Spaniards feel insecure in Spanish America and feared that the viceroys would embark on a Creole-friendly policy. They eventually rose against the old order, which in turn led to conflicts with the Creoles . They saw a good chance for independence. Contrary to previous statements of loyalty, the time had come for the Creoles to renounce Spain or the junta's constituent assembly in Cádiz. However, the junta refused to give the Creoles the same status as the Spaniards. Spanish America in particular suffered from the interruption of trade routes. Finally, the movement became so radical that in 1810 the viceroy of the Río de la Plata was deposed in Buenos Aires and a short time later the declaration of independence followed.

In the rest of Spanish America, Spain was able to consolidate its rule again after the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15. Venezuela, which after Rio de la Plata was the second focus of the independence movements, initially fell back to Spain. A short time later, however, the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar in northern South America and the Argentine José de San Martín from the Rio de la Plata area managed to achieve the military liberation of South America (with the exception of Portuguese Brazil ). When, after the introduction of the Cádiz Constitution in 1820, there was still no equality, the last undecided ran over to the camp of the liberation fighters.

The two old viceroyalty kingdoms of Peru and New Spain, which had undergone the most profound changes in the 18th century because of their colonial traditions, held the Spanish crown longest. It was not until 1821 that they broke away from the motherland. After the loss of Puerto Cabello in Venezuela (1823) and the defeat at Ayacucho in Peru (1824), Spain was left with only Cuba and Puerto Rico from the once huge colonial empire in America. The last base in Mexico, San Juan de Ulúa near Veracruz, surrendered in 1825. Then, in 1826, Ancud ( Chiloé ) in Chile was the last Spanish base in South America and thus on the entire American mainland. In the same year the Spaniards failed in a last attempt to retake Callao and Peru. A final attempt to retake Mexico from Cuba failed in September 1829.

In Asia, Spain was still able to hold the Spanish East Indies , which was converted into an independent crown colony after the independence of New Spain.

Put options

After the failure of the reconquest attempts (1829), Spain finally recognized the independence of Mexico (1836), Ecuador (1840) and gradually the other American states as well. In addition, because of the Carlist Wars that broke out in the interior, Spain hardly seemed to have the strength to maintain the remaining property. At least some of Queen Isabella II's regents or governments appeared to be interested in getting rid of some of the most unprofitable colonies. For example, regent María Cristina offered Great Britain, France and Belgium Cuba for sale in 1837 (and the Philippines at the same time), and after Mary's fall, talks were held with Great Britain from 1840 on the sale of the island of Fernando Póo . However, the planned sale of Fernando Póo for 60,000 pounds failed because of the resistance in the Cortes, as did the attempts by US Presidents James Polk and Franklin Pierce to buy Cuba for 100 and 130 million dollars (1849 and 1854) or the multiple attempts Belgium to buy the Philippines from Spain (1840, 1870–1875).

Restoration attempts

In order to divert attention from domestic political problems (struggles between liberals and conservatives, uprisings by Carlist and anarchists) and encouraged by an expansionist policy by France, Spain's head of government Leopoldo O'Donnell , who was also minister of war and colonial minister at the same time, began colonial foreign policy adventures. Initially, the Spanish and French fought together against Vietnam from 1858 after two Spanish missionaries had been executed there; In 1859 they succeeded in conquering Saigon . This was followed by a war against Morocco in 1859 , which only brought Tétouan and Ifni to Spain in 1860 . The Civil War that broke out in 1861 gave Spain the unexpected opportunity to intervene again in Latin America undisturbed by the US Monroe Doctrine . The prelude was the occupation of Santo Domingo , which could be subject to Spanish rule again from 1861–1865.

From December 1861, Spain, together with Great Britain and France, took part in an intervention in Mexico , but like England withdrew from the company in April 1862 because it did not share the French war aims (establishment of a pro-French regime in Mexico) . Spain also made peace with Vietnam in 1862. Instead, Queen Isabella II sent an expedition to South America, these attempts to restore Spanish rule in Latin America were therefore also known as Recuperación Isabelina . The Spanish occupation of the guano-rich Chincha Islands and an incident with Peru led to the Spanish-South American War in 1864 , which Spain did not want on this scale. O'Donnell's successor Ramón María Narváez had therefore offered Peru peace in 1865 and also gave up Santo Domingo again, but in June 1865 Narvaez was replaced by O'Donnell, and a civil war broke out in Peru, in the course of which the warring party to the Power came. Chile, Bolivia and Ecuador allied with Peru in 1866. With the bombing of Valparaíso (1866) and Callao, Spain only reached the protest of Great Britain and the USA, which had meanwhile ended their civil war, as well as a mutiny by the Spanish army that led to the renewed overthrow of O'Donnell. The Peruvians celebrated the withdrawal of the Spanish fleet as a victory, and after the United States forced France to withdraw from Mexico, they brokered peace between Spain and Peru. This could only be signed in Washington in 1871 because of the confusion of the throne that had broken out since Queen Isabella's overthrow in 1868.

The colonies were also affected by the civil war in Spain, which lasted until 1874, between the republicans, cantonalists, Carlists and military personnel close to Isabella's son. For example, the German Reich intervened briefly in Culebra in Puerto Rico and in Cuba an uprising had broken out as early as 1868, in which the USA interfered for the first time and which lasted until 1878 . A second uprising in Cuba was put down in 1880, the third Cuban War of Independence , which broke out in 1895 , finally culminated in the Spanish-American War in 1898 , in which Spain was crushed by the emerging United States and with it its last prestigious colonies not only in America, but also in Asia lost. Germany then forced Spain to sell the Mariana Islands and Caroline Islands, just as it had forced the sale of the Marshall Islands in 1885.

Spain had also tried in vain to gain a foothold on the east coast of Africa , on the Red Sea . After an Italian defeat against Ethiopia (January 1887) and the incorporation of Spain into the Mediterranean Entente (Italian-Spanish secret agreement, May 1887), Spain had received from Italy the promise to surrender a small piece of the Eritrean Danakil coast in the Bay of Assab (December 1887). Spain was supposed to lease the area (two miles south of Assab, between Buia and Mergabela / Margableh, near Alela, opposite the island of Um Ālbahār) for an initial 15 years and wanted to build a coal station there for the Spanish Navy on the sea route to the Philippines. Italy probably hoped to be able to include Spain in the defense of the Italian Assab colony . In view of Great Britain's opposition to this plan, Italy delayed relinquishing the area and, after interim successes against the Ethiopians, incorporated it into its own colony, Eritrea, in 1890 . When the Spanish-Italian agreement was extended in 1891, there was no longer any question of surrendering it to Spain. The agreement was then no longer renewed in 1895 and a station on the Red Sea became obsolete with the loss of the Philippines from 1898 onwards.

Only the insignificant colonies on the West African coast, Spanish Guinea and Spanish West Africa as well as Spanish Morocco remained of the once global Spanish empire . In Africa, Spain had acquired the Western Sahara after the Congo Conference (1884) and, after an interim defeat in the First Rif War (1909) as a result of the Second Morocco Crisis (1911), also the north of Morocco. In Morocco, however, in 1921 the Rifabyls under Abd el-Krim rose against Spanish rule, founded an independent Rif republic and again inflicted an embarrassing defeat on the Spanish colonial army at the Battle of Annual . It was not until 1926 that Spain was able to assert itself in the Second Rif War with French help .

Colonial plans of Francoist Spain

At the Hendaye conference, Hitler's dictator Franco had promised Gibraltar and territorial gains at the expense of France. In addition to French Morocco, Franco had called for the Mauritanian area between the Spanish Sahara and the 20th parallel, the Algerian Department of Oran (67,262 km²) and an expansion of the coastal area of Spanish Guinea. However, the head of state of Vichy France, Marshal Petain, refused to cede Morocco. German colonial plans also provided for Spanish Guinea for German Central Africa , while Sierra Leone or West Nigeria or Liberia were to fall to Spain as compensation.

In fact, in 1940 Spain only occupied Tangier, which had been administered internationally until then , and vacated it again under international pressure at the end of the war.

Todays situation

After the abandonment of Equatorial Guinea (1968) and Western Sahara (1976), only the African areas of Canary Islands , Ceuta and Melilla belong to Spain today . Although they are an integral part of Spain and the EU as autonomous regions or autonomous cities, Morocco still regards Ceuta and Melilla as areas that, contrary to the UN decolonization resolution of 1960, are still under colonial rule. While the proportion of the Moroccan-Muslim population in Ceuta is 41% and in Melilla just over 50%, the Canary Islands are dominated by a Spanish-Christian population. After Franco's death , Spain signed the Treaty of Madrid , in which Spain gave Mauritania and Morocco provisional sovereignty over Western Sahara. Today the contract is considered illegal and not valid. The Western Sahara de jure is still a Spanish colony.

A curiosity are the four mini archipelas Guedes, Coroa, Pescadores and Ocea in Micronesia, which were obviously forgotten in the German-Spanish treaty of 1899 and are therefore legally still Spanish territory. However, due to its minor importance, the land does not claim ownership.

The areas remaining with Spain are highlighted in yellow in the list below.

List of Spanish possessions and colonies

| Possession | Acquisition | loss | history |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balearic Islands | 1229 1344/49 |

1276 - |

conquered between 1229 and 1235 by James I of Aragón , in 1276 the brother of Peter III. from Aragón James II the Balearic Islands as well as the Catalan counties of Roussillon , Cerdanya and the rule of Montpellier to the independent Kingdom of Mallorca , 1344 recapture and reintegration into the Crown of Aragon, 1349 after the death of James III. of Mallorca finally Aragonese, today the Autonomous Community of Spain. Menorca is occupied by the British in 1708, then given to Great Britain in the Peace of Utrecht , French occupied in 1756, returned to Great Britain in 1763, recaptured by Spanish-French troops in 1782 , Spain reassigned in the Peace of Paris , British occupied again in 1798, the island finally returned in 1802 to Spain |

| Provence county | 1167 | 1267 | In 1167 King Alfonso II of Aragon acquired the county of Provence through inheritance law, then bound to the Crown of Aragon through secundogeniture , fell to the House of Anjou in 1267 |

| Duchy of Athens | 1311 | 1319 | by the Catalan Company conquered, united in 1319 with the Duchy Neopatria, spun off in 1388 and to the Florentine family Acciaiuoli passed |

| Duchy of Neopatria | 1319 | 1390 | Conquered by the Catalan Company and united with the Duchy of Athens, in 1379 under the direct administration of the Aragonese Crown, later sold to the Acciaiuoli family in Florence |

| Kingdom of Naples | 1442 1504 1735 |

1500 1714 1759 |

1422 reunification of Naples and Sicily by Alfonso V , 1458 again administered separately, briefly French between 1500 and 1504, reunification with Sicily by Ferdinand II in 1504 , henceforth a neighboring country of the Spanish crown, lost to Austria in the Peace of Rastatt in 1714, in peace in 1735 bound by Vienna to Spain again by secondary school, separated from Spain in 1759 by Ferdinand IV . |

| Kingdom of Sardinia | 1297 1409 |

1383 1707 |

Transferred as fief to James II by the Pope in 1297 , final conquest of the island in 1323, lost again to the Arborea judiciary in 1383, recapture in 1409, status as an Aragonese viceroyalty established in 1420, from the early 16th century in personal union with the newly established kingdom Spain united, occupied by Austria in 1707 and ceded to it in 1713 |

| Kingdom of Sicily | 1282 1735 |

1714 1759 |

1282 by the Sicilian Vespers at Aragon, 1442 union with the Kingdom of Naples, separated again in 1458, reunification in 1501 by Ferdinand II of Aragón , henceforth a neighboring country to the Spanish crown, in 1714 awarded to Viktor Amadeus II of Savoy, again in 1735 by the Peace of Vienna bound by Sekundogenitur to Spain by 1759 Ferdinand IV. separated from Spain |

| Corsica | 1297 1419 |

1347 1453 |

In 1297 Pope Boniface VIII transferred Corsica to King James II of Aragón as a fief, in 1325 conquered the entire island, in 1347 it fell back to Genoa, in 1372 again briefly Aragonese by Count of La Rocca, in 1401 in French, in 1410 back to Genoa, in 1419 back to Aragon back, 1447 division of the island: Aragon receives sovereignty over the southern lands of the lords of Cinarca, in 1453 finally to the Genoese bank Banca di San Giorgio |

| Malta | 1284 | 1525/1530 | 1284 conquest of Malta by the Aragonese-Sicilian fleet and subordinated to the viceroy of Sicily, in 1525 assigned to the Order of St. John as a fief by Charles V , in 1530 finally owned by the Order of St. John through a papal bull |

| Reign of Montpellier | 1204 | 1349 | In 1204 she fell to Aragón through the marriage of Mary of Montpellier to Peter II , became the independent kingdom of Mallorca in 1276, and in 1349 through James III. Mallorca to France sold |

| Northern Catalonia ( Carcassonne , Roussillon ) | 1137 | 1659 | 1276 incorporation of the counties of Roussillon and Cerdanya into the independent kingdom of Mallorca , 1344 the Aragonese recapture of Roussillon, 1403 Cerdanyas, ceded to France in 1659 by the Peace of the Pyrenees |

|

Kingdom of Navarre (Obernavarra) |

1076 1419 |

1134 1431 |

united with the Kingdom of Aragon between 1076 and 1134 , then again independent, between 1419 and 1431 viceroyalty of the Crown of Aragon, disputed between the now Spanish crown and the French noble family Grailly since the end of the 15th century , 1512 conquest of the southern part of Navarre (Upper Navarra) through Spain, the northern part (Niedernavarra) goes to the French house of Albret in 1516 , administered as the Viceroyalty of Spain until 1702 , today as the Navarra Autonomous Community of Spain |

| Possession | Acquisition | loss | history |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | |||

| Elba | 1557 | 1709 | 1557 capture of Porto Longone , later part of the Spanish garrison state, lost in the War of the Spanish Succession in 1709 , officially ceded to the Austrian-ruled Kingdom of Naples in 1714 |

| Franche-Comté (Free County of Burgundy) | 1556 | 1678 | Fallen to Spain in 1556 through inheritance, occupied by France in the War of Devolution in 1668 and in the Dutch War in 1674, finally ceded to France in 1678 in the Peace of Nijmegen |

| Charolais county | 1556 | 1684 | In 1477 it fell to the House of Habsburg as part of the Burgundian inheritance, but still under the feudal sovereignty and the legal area of the French crown, in 1556 by distribution of the estate to Spain, in 1684 by a treaty between King Philip IV of Spain and Louis II de Bourbon, prince de Condé handed over to him |

| Duchy of Milan | 1535 | 1714 | Conquered by Emperor Charles V in 1535 and handed over to his son Philipp , united in personal union with Spain since 1556, lost to Austria in 1714 through the War of the Spanish Succession |

| Monaco | 1542 | 1641 | Spanish protectorate |

| Spanish Netherlands | 1556 | 1714 | Fell in 1556 by inheritance to Spain, in 1579 the northern part of the Union of Utrecht independently, the southern part, the Union of Arras remains in Spain and is henceforth referred to as Spanish Netherlands, in the Eighty Years' War come Flanders and Brabant added, in the Pyrenees peace and Devolution occurs Spain the Counties of Artois , Gravelines , Landrecy , Diedenhofen , Le Quesnoy , Montmédy , Lille , Charleroi , Oudenaarde and Kortrijk to France, in the Peace of Nijmegen in 1679 and in the Peace of Rijswijk parts of these areas come back to Spain, in 1714 due to the War of the Spanish Succession to Austria assigned |

| Siena | 1524 1555 |

1552 1557 |

From 1524 under the protection of Emperor Charles V , who installed a Spanish administration, 1552 expulsion of the Spaniards with French help, 1555 reconquest of Siena by the Florentine imperial lord, 1557 enfeoffment of Cosimo I de 'Medici with the city by Philip II of Spain which it into the Grand Duchy of Tuscany annexing |

|

Stato dei Presidi (Spanish Garrison State) |

1557 1735 |

1707 1759 |

1522 under the protection of Emperor Charles V , 1555 conquest of Siena and foundation of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany by Cosimo I de 'Medici , on July 3, 1557 Orbetello , Porto Ercole , Porto Santo Stefano , Talamone , Ansedonia , Porto Longone and parts of Elba returned to Spain and founding of the Stato dei Presidi, occupied by Austria in 1707 , returned to Spain in the preliminary peace of Vienna in 1735 , bound to the Kingdom of Naples in 1759 |

| Portugal | 1580 | 1640 | united in personal union with Spain through marriage contracts from 1580, independent again in 1640, war until independence was recognized in 1666 |

| final | 1571 | 1713 | Conquered by the Spanish governor of Milan in 1571, then officially under Spanish rule in 1602, lost to Genoa in 1713 |

| Principality of Piombino | 1590 | 1796 | from 1590 under Spanish influence, in 1628 transferred to Philip IV of Spain as a fief, in 1634 fallen to the Ludovisi family, but still dependent on Spain, conquered and occupied by French revolutionary troops in 1796 |

| Duchy of Parma | 1731 | 1735 | by inheritance to Charles III. fell from Spain , handed over to the Habsburgs in 1735 |

| Africa | |||

| Spanish Guinea | 1788 | 1968 | ceded by Portugal to Spain, independent as Equatorial Guinea in 1968 |

| Spanish West Africa | 1934 | 1969/1976 | In 1860 Ifni was acquired by Spain, in 1884 the Spanish Sahara became a Spanish colony as Rio de Oro, in 1934 the two colonies merged, in 1969 Ifni became part of Morocco, occupied by Morocco and Mauritania in 1976 , now annexed by Morocco, international status unclear |

| Djerba | 1551 | 1560 | from 1520 Spanish vassal , 1551 direct Spanish administration, occupied 1560, fallen to the Ottoman Empire in the naval battle of Djerba |

| Bizerta | 1535 | 1574 | Conquered by Emperor Charles V in 1535, transferred to the Ottoman Empire in 1574 |

| Bejaia (bougie) | 1510 | 1555 | Conquered by Spain in 1510, transferred to the Ottoman Empire in 1555 |

| Oran | 1509 1732 |

1708 1792 |

In 1505 and 1506 first attempts to conquer the city, in 1509 the city was captured and a Spanish government was established, lost to the Ottoman Empire in 1709, recaptured from Spain in 1732, peace talks with the Ottoman Empire from 1790, then handed over to the Ottoman Empire in 1792 |

|

Mers El Kébir (Mazalquivir) |

1505 1708 |

1732 1792 |

Conquered for Spain by Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros in 1505 , Ottoman in 1708, Spanish again in 1732, sold to the Ottoman Empire in 1792 |

| Penon de Algiers | 1510 1573 |

1529 1574 |

Spanish occupied in the course of the conquest of Orange in 1510, under the protection of the Ottoman Empire in 1529, briefly Spanish again in 1573, and finally Ottoman in 1574 |

| Tripoli | 1509 | 1530/1551 | Conquered for Spain in 1509 by Count Pietro of Navarre and installed by a Spanish governor, transferred the Order of St. John as a fief by Emperor Charles V in 1530 , lost to the Ottoman Empire in 1551 |

| Mahdia | 1550 | 1553 | Conquered by the Spanish fleet in 1550 and subordinated to the Viceroy of Sicily, again Ottoman in 1553 |

|

Honaine (Oney) |

1531 | 1534 | Occupied by Spain in 1531, lost again to the Ottomans in 1534 |

|

Annaba (Bona) |

1535 1636 |

1541 1641 |

Conquered by Spain in 1535, again Ottoman in 1541, ninth Spanish conquest in 1636, lost to Genoa in 1641 |

|

Sousse (Susa) |