Santa Fe surrender

With the surrender of Santa Fe ( Spanish Capitulaciones de Santa Fe ), the Castilian royal couple Isabella and Ferdinand commissioned the navigator Christopher Columbus on April 17, 1492 in the army camp of Santa Fe to undertake a voyage of discovery into the Atlantic Ocean with the aim of “goods of any kind, be it pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices and other things, to buy, barter, find and acquire. ”In return, he was given high government offices in the areas he discovered and profits from trading with them Areas assured.

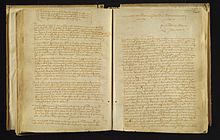

The copy of the Surrenders of Santa Fe, kept in the archives of the Crown of Aragon in Barcelona, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2009 .

Definition of the term surrender

To finance voyages of discovery and expeditions of conquest by private investors, the Crown of Castile developed the surrenders at the end of the 15th century . They summarized the results of the negotiations between the capitulators and representatives of the crown. They contained the services to be provided by the capitulators and the promises of the crown. In terms of formal law, these documents did not constitute contracts , as they only contained a declaration of intent in the name of the king or queen and were not signed by the capitulators. The surrenders not only dealt with civil law claims such as the distribution of profits from trading companies, but also assured tax advantages or administrative ("civil service") commitments made by paid state offices, which are inconceivable in a bilateral contract among equals. It is controversial whether the promised privileges were enforceable. In any case, the holders of the offices conferred for life by the surrender were not protected from impeachment due to poor performance.

prehistory

In 1484 Columbus presented his plan to reach the countries of origin of luxury goods such as silk and spices by sea to the west of the Portuguese King John II in order to get ships and crews from him with whom he wanted to travel to Cipangu . The king commissioned a commission of experts to examine the plan. The latter declined to support such a trip.

After the death of his wife, Columbus traveled to Palos in the Kingdom of Seville in 1485 . In the Franciscan monastery of La Rábida he met Fray Antonio de Marchena. He brought him together with the Duke of Medinaceli. In May 1486, Columbus was able to present his project to Queen Isabella of Castile in person for the first time in Cordoba .

Like the King of Portugal, the Queen and King of Castile also convened a commission of astronomers , cartographers and seafarers .

The experts, chaired by the royal confessor Hernando de Talavera, examined Columbus' plan in the last months of 1486 and the first in 1487 and discussed various aspects of its implementation with him. The commission concluded that Columbus' numbers for the distance between the countries in the east and the circumference of the earth were incorrect.

The rulers let Columbus know that they were not currently interested in the plan, that they had other more pressing matters to attend to, and that they would come back to it later when the opportunity was better. It is believed that this rather veiled message to Columbus, in which any reference to the unfavorable decision of the assembly was avoided, was due to the influence of Diego de Dezas , the then teacher of Crown Prince Johann.

When the victory in the war against the emirate of Granada was foreseeable in the winter of 1491, Queen Isabella received Columbus in the military camp of Santa Fe, near Granada. The content and the course of the conversation are not known. As a result, however, the queen again convened a commission of experts who dealt with the plans, but also with Columbus' demands. In the commission, which again met under the chairmanship of Queen Hernando Talavera’s confessor at the time, the proponents of the project were more strongly represented than in the previous commission. Decisive for the again negative decision were the explanations of the cosmographers and seafarers, who clearly made it clear that Columbus' calculations were wrong. Their viewpoints prevailed and the final verdict concluded that the plan for the trip was completely impracticable. Columbus's demands, such as the appointment of viceroy and promotion to admiral , were also rejected on behalf of a foreigner. When Columbus learned of the renewed rejection of his project, he is said to have left immediately for Palos.

After the conversation between the queen and Columbus, Luis de Santángel , King Ferdinand's treasurer, appears to have changed the queen's mind. He argued that the support of Columbus' plan for the crown was hardly a risk, since the promises would only be made if the trip was successful. Luis de Santángel agreed to cover part of the cost of equipping the ships. Columbus can have the rest of his friends and business people advance him. The ships could be paid for from the funds the city of Palos owed the Crown. Columbus was ordered by a messenger to return to Santa Fe for negotiations.

King Ferdinand decided that the matter should be dealt with by only two people: Hernando de Talavera and Diego de Deza. Both should come together with Christopher Columbus to reach an agreement. In the following three months the representatives of the Crown of Castile and Columbus negotiated the conditions under which the expedition should be carried out. On April 17, 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella signed the capitulations along with other documents relating to the trip.

Purpose of Travel

The purpose of the trip is not explicitly stated in the text of the surrenders. Islands and mainlands in the Atlantic Ocean should be discovered and won. The land discovered was to be taken possession of for the queen and king. The appointments as viceroy and governor indicate the intention to create a permanent connection between the lands to be discovered by Columbus and the kings of Castile. The equipment of the expedition does not suggest that settlement colonies should be established. Missioning the population of the newly discovered areas was not intended, at least on the first trip. Among the 87 participants in the expedition were two officers to monitor compliance with the agreements, a clerk to record the conquest, and an interpreter with knowledge of Arabic and Hebrew to contact the strangers, but there was no clergyman.

It is likely that the long-term purpose of the trip was to build trade bases along the lines of the Portuguese in West Africa. The surrenders say that goods of all kinds, be they pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices and other things, should be bought, exchanged, found and acquired.

Content of the surrenders

Duties of Columbus

The duties of the surrender are not specifically listed in the Santa Fe surrenders. From the text, however, the obligation arises to undertake a trip to the Atlantic Ocean and to discover islands and mainland there and to take possession of them on behalf of the Queen and the King. In addition, Columbus was supposed to acquire valuable goods for the queen and the king.

Promises of the Crown in relation to offices

- Columbus was assured the title of admiral with all associated rights in all areas he discovered. Associated with this was an elevation into the high nobility . The title should be inheritable.

- From this office it emerged that Columbus was to be appointed judge in all disputes that would arise in the future from the trade with the areas he had discovered.

- Columbus was to receive the position of viceroy and governor in all areas he discovered, with the right to propose three candidates for each office to be appointed, one of which should be selected by the crown.

Commitments from the Crown in relation to economic benefits

- Columbus should be entitled to one tenth of all goods traded in the discovered areas.

- Columbus should be entitled to share one eighth of the equipment costs for every ship that sailed into the areas he discovered and receive an eighth of the profit made in return.

Dispute over the concessions

After Columbus' first voyages, the queen and the king began to restrict the concessions granted to him in the surrender of Santa Fe. Due to complaints from the colonists, the queen and the king sent, as was customary at the time, an examining magistrate (juez pesquisidor) to Santo Domingo, who was given full powers to review Columbus' administration as viceroy and governor and at the same time for the duration of the investigation Should take governance. The following processes, revisions of measures, and new procedures dragged on after Columbus' death in 1506 until the mid-1530s.

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard Konetzke: Latin America since 1492 . Klett, Stuttgart 1970, p. 3 . quoted from Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Introduction to the Early Modern Age. Historical seminar of the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, 2003, accessed on June 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Santa Fe Capitulations. UNESCO, 2017, accessed June 1, 2019 .

- ^ Horst Pietschmann: The state organization of colonial Ibero America . Handbook of Latin American History: Partially published. 1st edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911410-6 , pp. 21 f .

- ↑ Marta Milagros de Vas Mingo: Las capitulaciones de Indias en el siglo XVI . Instituto de cooperación iberoamericana, Madrid 1986, ISBN 84-7232-397-8 , p. 43 f (Spanish).

- ^ Horst Pietschmann: The state organization of colonial Ibero America . Handbook of Latin American History: Partially published. 1st edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911410-6 , pp. 29 .

- ^ Miguel Molina Martínez: Fray Hernando de Talavera y Colón . In: Navegamérica . No. 1 , 2008, ISSN 1989-211X , p. 5 f (Spanish, [1] [accessed July 1, 2019]).

- ^ Miguel Molina Martínez: Fray Hernando de Talavera y Colón . In: Navegamérica . No. 1 , 2008, ISSN 1989-211X , p. 7 (Spanish, [2] [accessed July 1, 2019]).

- ^ Miguel Molina Martínez: Fray Hernando de Talavera y Colón . In: Navegamérica . No. 1 , 2008, ISSN 1989-211X , p. 8 (Spanish, [3] [accessed July 1, 2019]).

- ^ Miguel Molina Martínez: Fray Hernando de Talavera y Colón . In: Navegamérica . No. 1 , 2008, ISSN 1989-211X , p. 9 (Spanish, [4] [accessed July 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Urs Bitterli: The discovery of America: from Columbus to Alexander von Humboldt . New edition edition. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 978-3-406-42122-8 , pp. 50 ff .

- ↑ Urs Bitterli: The discovery of America: from Columbus to Alexander von Humboldt . New edition edition. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 978-3-406-42122-8 , pp. 56 .

- ^ Richard Konetzke: Latin America since 1492 . Klett, Stuttgart 1970, p. 3 . quoted from Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Introduction to the Early Modern Age. Historical seminar of the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, 2003, accessed on June 1, 2019 .

- ^ Horst Pietschmann: The state organization of colonial Ibero America . Handbook of Latin American History: Partially published. 1st edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911410-6 , pp. 29 .

literature

- Urs Bitterli: The discovery of America: from Columbus to Alexander von Humboldt . New edition edition. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 978-3-406-42122-8 .

- Miguel Molina Martínez: Fray Hernando de Talavera y Colón . In: Navegamérica . No. 1 , 2008, ISSN 1989-211X , p. 1–16 (Spanish, [5] [accessed July 1, 2019]).

- Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Introduction to the Early Modern Age. Historical seminar of the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, 2003, accessed on June 1, 2019 .

- Horst Pietschmann: The state organization of colonial Ibero America . Handbook of Latin American History: Partially published. 1st edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911410-6 .

- Horst Pietschmann: Estado y conquistadores: Las Capitulaciones . In: Historia . No. 22 , 1987, pp. 249–262 (Spanish, [6] [accessed February 3, 2018]).

- Marta Milagros de Vas Mingo: Las capitulaciones de Indias en el siglo XVI . Instituto de cooperación iberoamericana, Madrid 1986, ISBN 84-7232-397-8 (Spanish).