Pacific Crest Trail

| Pacific Crest Trail | |

|---|---|

Pacific Crest Trail in the Ansel Adams Wilderness , overlooking the Knights Range |

|

| Data | |

| length | around 4,265 km |

| location | California , Oregon , Washington |

| Markers |

|

| Starting point |

Campo , California 32 ° 35 ′ 23.4 " N , 116 ° 28 ′ 1.1" W. |

| Target point |

Manning Park , British Columbia 49 ° 0 ′ 1.9 " N , 120 ° 47 ′ 59.3" W. |

| Type | Long-distance hiking trail |

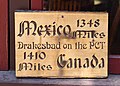

The Pacific Crest Trail ( PCT for short , officially Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail ) is a 4265 kilometer (2650 mile) long- distance hiking and horse riding trail along the ridges of the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range . Together with the Appalachian Trail and the Continental Divide Trail , it is one of the three triple-crown hiking trails, making it one of the longest and most challenging long-distance hiking trails in the United States . Hikers who hike the Pacific Crest Trail in one season are called "PCT Thruhikers ".

The trail runs parallel to the Pacific coast, which is 160 to 240 kilometers further west, through the American states of California , Oregon and Washington . The southern end point of the Pacific Crest Trail is south of the village of Campo on the United States' border with Mexico , and the northern end point is on the border with Canada on the edge of Manning Provincial Park in British Columbia . The highest point is reached at Forester Pass in California at 4009 meters. A significant part of the Pacific Crest Trail runs through areas that are designated as Wilderness Area , National Monument , or National Park in the USA .

In 1968, the Pacific Crest Trail, together with the Appalachian Trail, became the first hiking trail in the United States to receive National Scenic Trail status . In 1993, 25 years after the National Trails System Act was passed, the Pacific Crest Trail was officially inaugurated.

Today the Pacific Crest Trail is maintained by the US Forest Service on behalf of the United States government. Care is supported by the National Park Service , the Bureau of Land Management , the California Department of Parks and Recreation, and the Pacific Crest Trail Association .

history

Catherine Montgomery, the "mother of the Pacific Crest Trail"

The first evidence for the idea of hiking the mountain ridges in the western United States parallel to the Pacific can be found in Joseph Taylor Hazard (1879-1965) in his 1946 published book Pacific Crest Trails . Hazard, himself an avid mountain hiker, states that Catherine Montgomery (1867–1957) of the Western Washington College of Education in Bellingham had “A high-altitude hiking trail over the peaks of our western mountains with trail markers and shelters at an event of the Mount Baker Club […] From the border with Canada to the border line with Mexico ”. Based on this illustration, the Pacific Crest Trail Association now regards Montgomery as the "Mother of the Pacific Crest Trail".

Start of implementation: Frederick W. Cleator

The implementation of this idea was picked up in the late 1920s by Frederick William Cleator (1883–1957), who worked as Supervisor of Recreation for Region 6 in Oregon and Washington for the US Forest Service. Cleator began developing the Cascade Crest Trail and then the Oregon Skyline Trail to create a continuous route from Canada to the Columbia River . In 1937, US Forest Service Region 6 employees began marking the route from the Canadian border to California with continuous trail markings.

Clinton C. Clarke and the Pacific Crest Trail System Conference

The administration of Region 5 (California) did not initially endorse the idea of the multi-state hiking trail. It is thanks to the private initiative of Clinton C. Clarke (1873–1957) from Pasadena that the concept of the Pacific Crest Trail was finally implemented in its entirety. During his tenure as chairman of the Mountain League of Los Angeles County in March 1932, Clarke wrote to the US Forest Service and the National Park Service requesting that they set up a “continuous hiking trail through the United States, from Canada to Mexico […] of the summit ridges [...] passing through the best viewpoints and while strictly maintaining the character as wilderness ”. Over the next 25 years, as President of the Pacific Crest Trail System Conference, which he founded, Clarke pushed this plan further, played a leading role in the expansion of the John Muir Trail north and south and published a manual on the Pacific Crest Trail in 1935 under the title The Pacific crest trail, Canada to Mexico . Because of this special role, Clarke is now often referred to as the "father of the Pacific Crest Trail".

The National Trail Systems Act

In October 1968, the United States Congress voted for the National Trails System Act , a law to create a national network of hiking trails. The law aimed to give the population access to outdoor recreation and at the same time to put certain parts of nature under protection. As the first two National Scenic Trails , the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail became law. The PCT was thus officially recognized and classified as worthy of protection.

Founding of the PCTA and official inauguration in 1993

In the course of the further expansion of the Pacific Crest Trail, Warren Lee Rogers (1908-1992), a companion of Clinton Clarkes, founded the Pacific Crest Trail Club in 1972 , which in 1992 was merged with the Pacific Crest Trail System Conference to form the Pacific Crest Trail Association (PCTA) . Since then, this non-profit organization has been committed to protecting, maintaining and promoting the hiking trail and offers detailed information for hikers on its website.

One year after Rogers death, the Pacific Crest Trail was officially inaugurated, officially completing the work of Clarke and Rogers. However, since individual sections of the hiking trail still lead over private land to this day, there are repeated attempts to buy it up and to further optimize the course of the Pacific Crest Trail.

The route

Length of the route

There are different information about the exact length of the Pacific Crest Trail. For example, the Englishman Keith Foskett, who successfully completed his hike on the PCT in 2010 after seven months, gives the length as 4249 kilometers, while the German Thruhiker Christine Thürmer puts the length at 4277 kilometers. The Pacific Crest Trail Association explains such differences by pointing out that the length of the PCT fluctuates from year to year due to route changes. In addition, the PCT has never been measured with technical aids in such a way that its length can be specified with sufficient accuracy. The Pacific Crest Trail Association itself has set the official length at 2,650 miles (4,265 kilometers) and justified this with the fact that, given the frequent route adjustments, they cannot reprint their t-shirts and signs every year. According to their FAQ , the specification of 2650 miles to approximately "ten miles more or less" is correct.

Overview of the route

The trail runs through the Sierra Nevada in California ; at times it is identical to the John Muir Trail . It then runs over the ridge of the Cascade Range in Northern California, Oregon and Washington .

A significant part of the Pacific Crest Trail runs in wilderness areas such as the Desolation Wilderness or the Three Sisters Wilderness , national monuments such as the Sand to Snow National Monument or the Devils Postpile National Monument , as well as national parks such as the Kings Canyon National Park , the Yosemite National Park or Lassen Volcanic National Park .

Since individual sections of the route are repeatedly affected by the forest fires that occur in California and are therefore closed to hikers, the exact course of the route can vary from year to year. A major change in the route is the relocation of a 37-mile (around 60 km) long section in the Mojave Desert to the ridge of the Tehachapi Mountains , promoted by the Pacific Crest Trail Association . The previous route of the trail in this area is along more natural areas of the California Aqueduct and is considered to be one of the least appealing sections of the Pacific Crest Trail. After a fundamental agreement was reached in 2008 with the Tejon Ranch Company as the owner of the area, this plan has not yet been implemented and, according to the Pacific Crest Trail Association, as of 2020, it will take years for this route to be completed can be.

| section | Length (in miles) | By mile | Until mile | image | description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA Section A | 109.5 | 0 - Campo (Mexican Border) | 109.5 - Warner Springs | The PCT begins on the Mexican border near the small town of Campo. While temperatures of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit (37 degrees Celsius) are often reached in the lower parts of this first section in late spring, hikers in the Laguna Mountains can still be surprised by snowstorms in April and May . The path leads west past the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and grazes it in the meantime. | |

| CA Section B | 100.0 | 109.5 - Warner Springs | 209.5 - Interstate 10 (Cabazon) | The trail crosses the northwestern tip of the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument on the ridge of the Peninsular Ranges that run parallel to the Pacific coast . The first mountainous section of the route is reached with the San Jacinto Mountains . On the way from the San Jacinto Mountains to the San Gorgonio Pass , there is a descent of around 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) to overcome. | |

| CA Section C | 132.5 | 209.5 - Interstate 10 (Cabazon) | 342.0 - Interstate 15 ( Cajon Pass ) | From the San Gorgonio Pass, it goes through the San Bernardino Mountains . The PCT crosses the San Andreas Fault . In April or May, hikers can expect hail, snow and sub-freezing nighttime temperatures. The section ends in Cajon Canyon under the six-lane Interstate 15 . | |

| CA Section D | 112.5 | 342.0 - Interstate 15 (Cajon Pass) | 454.5 - Agua Dulce | To the northeast of Los Angeles, the PCT runs over the ridges of the San Gabriel Mountains . With the 2865 meter high Mount Baden-Powell the fourth highest peak of the mountain range is climbed. At the end of this section, the hikers reach the small village of Agua Dulce , which, according to the travel guide of the Wilderness Press series, "probably has the highest concentration of committed" trail angels "along the PCT". | |

| CA Section E | 115.0 | 454.5 - Agua Dulce | 566.5 - Tehachapi Pass (Tehachapi) | ||

| CA Section F | 85.5 | 566.5 - Tehachapi Pass (Tehachapi) | 652.0 - Walker Pass (Onyx, Kernville) | ||

| CA Section G | 115.0 | 652.0 - Walker Pass (Onyx, Kernville) | 767.0 - Crabtree Meadows ( Mount Whitney ) | In Kennedy Meadows, hikers reach the "gateway to the High Sierra " and - at the end of the section - Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the United States outside of Alaska at 4421 meters. Although climbing Mount Whitney is not part of the PCT, some Thruhikers do it. | |

| CA Section H | 175.5 | 767.0 - Crabtree Meadows (Mount Whitney) | 942.5 - Highway 120 (Tuolumne Meadows) | The route from Mount Whitney to Tuolumne Meadows leads through a mountain landscape that is considered one of the most beautiful in the USA by hikers. The landscape is characterized by granite rocks, gorges and mountain lakes. With the Forester Pass at 4009 meters the highest point of the Pacific Crest Trail is reached. For most of the route, the PCT follows the John Muir Trail in this section . At the end of the section, the Ansel Adams Wilderness with the Devils Postpile National Monument is hiked through before the southeastern part of the Yosemite National Park is reached. | |

| CA Section I. | 74.4 | 942.5 - Highway 120 (Tuolumne Meadows) | 1016.9 - Highway 108 (Sonora Pass) to Bridgeport | From Tuolumne Meadows the path continues through Yosemite National Park, with the PCT coinciding with the Tahoe – Yosemite Trail almost to the north end of the park . The section is characterized by deep, glaciated canyons, which the travel guide for the Wilderness Press series notes that sometimes it feels more like climbing vertically than hiking horizontally. | |

| CA Section J | 75.4 | 1016.9 - Highway 108 (Sonora Pass) to Bridgeport | 1092.3 - Echo Lake (South Lake Tahoe) | From the second highest pass in the Sierra Nevada, the Sonora Pass , you continue to the glacial lake Echo Lake, south of Lake Tahoe . In the meantime, the granite landscape of the High Sierra has merged into a volcanic landscape that extends to Castle Crags State Park in northern California. | |

| CA Section K | 64.8 | 1092.3 - Echo Lake (South Lake Tahoe) | 1157.1 - Donner Summit (Interstate 80 to Truckee) | This section runs west of Lake Tahoe through the Desolation Wilderness and the Granite Chief Wilderness . Then the path leads along the Squaw Valley ski region to the Donner Pass, named after the Donner Party . | |

| CA Section L | 38.3 | 1157.1 - Donner Summit (Interstate 80 to Truckee) | 1195.4 - Highway 49 (Sierra City) | ||

| CA Section M | 89.0 | 1195.4 - Highway 49 (Sierra City) | 1286.9 - Highway 70 (Beldon) | ||

| CA Section N | 132.2 | 1286.9 - Highway 70 (Beldon) | 1419.0 - McArthur-Burney Falls State Park | Here the PCT reaches the southern cascade chain . The path leads through the volcanic landscape of the Lassen Volcanic National Park . In this section, half of the route is reached with the midway point . | |

| CA Section O | 82.2 | 1419.0 - McArthur-Burney Falls State Park | 1501.2 - Interstate 5 (Castle Crag-Castella) | ||

| CA Section P | 98.5 | 1501.2 - Interstate 5 (Castle Crag-Castella) | 1599.7 - Etna Summit (Etna) | ||

| CA Section Q | 56.2 | 1599.7 - Etna Summit (Etna) | 1655.9 - Seiad Valley | ||

| OR Section A | 63.0 | 1655.9 - Seiad Valley | 1718.9 - Interstate 5 (Callahan's-Ashland) | ||

| OR Section B | 54.5 | 1718.9 - Interstate 5 (Callahan's-Ashland) | 1847.8 - Highway 140 (Fish Lake) | ||

| OR Section C | 74.4 | 1718.9 - Highway 140 (Fish Lake) | 1847.8 - Highway 138 (Cascade Crest) | ||

| OR Section D | 60.1 | 1847.8 - Highway 138 (Cascade Crest) | 1907.9 - Highway 58 (Willamette Pass) | ||

| OR Section E | 75.9 | 1907.9 - Highway 58 (Willamette Pass) | 1983.8 - Highway 242 (McKenzie Pass - Sisters & Bend) | ||

| OR Section F | 107.9 | 1983.8 - Highway 242 (McKenzie Pass - Sisters & Bend) | 2091.7 - Highway 35 (Barlow Pass) | ||

| OR Section G | 55.2 | 2091.7 - Highway 35 (Barlow Pass) | 2146.9 - Cascade Locks (Bridge of the Gods) | ||

| WA Section H | 148.0 | 2146.9 - Cascade Locks (Bridge of the Gods) | 2294.9 - Highway 12 (White Pass - Packwood) | ||

| WA Section I | 98.3 | 2294.9 - Highway 12 (White Pass - Packwood) | 2393.2 - Interstate 90 (Snoqualmie Pass) | ||

| WA Section J | 70.9 | 2393.2 - Interstate 90 (Snoqualmie Pass) | 2462.1 - Highway 2 (Stevens Pass - Skykomish) | ||

| WA Section K | 127.0 | 2462.1 - Highway 2 (Stevens Pass - Skykomish) | 2591.1 - Highway 20-Rainy Pass (Mazama & Winthrop) | ||

| WA Section L | 70.3 | 2591.1 - Highway 20-Rainy Pass (Mazama & Winthrop) | 2661.4 - Highway 3 (Manning Provincial Park) |

The people

walker

The Pacific Crest Trail is used by different types of hikers. Especially in the national parks and other touristic areas, weekenders use parts of the Pacific Crest Trail for short hikes. These weekend hikers are to be distinguished from the "Thruhiker" long-distance hikers who try to conquer the path in one season, as well as the "Section hiker" who hike through individual sections or a series of sections within a certain period of time. For several years in a row, some section hikers hike a series of contiguous sections only to be hiked the entire Pacific Crest Trail at some point.

The number of Thruhikers on the Pacific Crest Trail has multiplied in the past decade. An approximate insight into this development is provided by the number of hiking permits recorded by the Pacific Crest Trail Association , which grant their holders certain rights such as free overnight stays in the wilderness. According to the Pacific Crest Trail Association, the number of Thruhike permits in 2019 was 5,441. For 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States , the organization has made a call to only hike local routes to do this to counteract the further spread of the coronavirus.

| year | Thruhike permits | Section hike permits | total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 5441 | 2437 | 7878 |

| 2018 | 4991 | 2304 | 7295 |

| 2017 | 3928 | 2132 | 6060 |

| 2016 | 3493 | 2151 | 5644 |

| 2015 | 2808 | 1633 | 4441 |

| 2014 | 1461 | 1179 | 2640 |

| 2013 | 1041 | 834 | 1875 |

However, these numbers are not indicative of how many of these Thruhikers completed the Pacific Crest Trail in that particular season. The Pacific Crest Trail Association also maintains a “2,600 miler list”, but this is based on voluntary information and is therefore incomplete at best. In the literature it is stated again and again that there are more people who have climbed Mount Everest than have hiked the Pacific Crest Trail in one season.

As far as the motivation of the hikers is concerned, the numerous printed reports as well as the video diaries and documentaries available online provide more precise information, at least for the Thruhikers. The 2013 documentary Tell It On the Mountain - Tales from the Pacific Crest Trail named the most common reasons for thruhiking: the beauty of nature, the remoteness of the landscapes you walked through, the camaraderie with other hikers and the loneliness during long-distance hikes. Some Thruhics and later authors of experience reports also point out that their decision to migrate was triggered by a critical life event such as the loss of their job or the death of a loved one. This aspect received special attention in the course of the publication of the book Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail by Cheryl Strayed and its later film adaptation (German: The Big Trip - Wild ).

Before starting their long-distance hike, many PCT Thruhikers have to plan and prepare intensively. This has to do with the fact that the hike seldom takes less than five months in one season and represents an enormous physical and mental challenge for the Thruhiker. At the same time, the long-distance hikers are under time pressure from the start in their attempt to tackle the northern sections of the route in Washington before the onset of winter. In addition, it is important to take into account the snow and temperature conditions in the High Sierra and other alpine regions, as the snow makes it difficult to find one's way around the terrain and, in the thaw, rivers can only be crossed at risk of death. For some Thruhikers, surviving dangerous situations in the remote wilderness of the mountains is what makes the Pacific Crest Trail so special.

Over the years a special culture has developed among the Thruhik people, which is reflected, among other things, in a common language. For example, Thruhikers speak of “Zero Days” or “Zeros” for short when they mean days when they rest and don't cover a single mile. It has also become common for long-distance hikers to adopt a “trail name” that is often given by other Thruhikers and refers - mostly in a joke - to a typical characteristic or other specialty. The German Thruhiker Christine Thürmer was given the trail name "German Tourist" on the Pacific Crest Trail, which she also used on later long-distance hikes. The concept of ultralight hiking , which was first promoted by the American PCT Thruhiker Ray Jardine in his 1992 book PCT Hiker's Handbook, plays a major role in Thruhiker culture . Like other aspects of Thruhiker culture, ultralight hiking is not limited to the Pacific Crest Trail, but is also cultivated on the other two Triple Crown long-distance hiking trails and beyond.

equestrian

According to the Pacific Crest Trail Association, riders only face the challenge of riding the entire distance from Mexico to Canada in one season every few years. Overall, few people in the history of the Pacific Crest Trail have successfully mastered a Thruride . One of the reasons for this is that successfully tackling the trail on horses requires a far greater amount of planning and preparation than walking on two legs. Not only do large quantities of horse feed have to be planned for in the logistics, it is also important to note that the riders - unlike the Thruhikers who often hitchhike to towns - cannot get to cities without problems in some cases. In addition, riders are much more dependent than hikers on correct information about the condition of the path ahead. The Pacific Crest Trail Association recommends that riders seek help from a team when attempting a thruride . The organization also advises tackling Thrurides with a riding partner. Overall, the PCTA rates at least sections of the trail as “hard and merciless” and advises riders not to overestimate their own abilities and those of their horses.

Trail Angels

The "Trail Angels" are an integral part of the Thruhiker culture of the Pacific Crest Trail. They are voluntary helpers who support Thruhiker in a variety of ways and sometimes at great expense. Some of the Trail Angels live near the long-distance hiking trail and make their house available for overnight stays and as an “unofficial post office”. Many Thruhikers send themselves so-called "bounce boxes" during the hike, in which they keep certain items of equipment that they will only need again on a later stretch of the route. In addition, the Thruhikers are mostly provided by relatives and friends with food supplies or replacement equipment, which are kept by some trail angels in addition to post offices . In addition, such trail angels let the Thruhikers camp on their property, provide them with washing facilities, cook food for them, and give them moral support. They are often motivated by getting to know interesting people, but are compensated by the Thruhikers by sharing expenses and not least by stories from the hike. Other trail angels drive their cars to certain points along the hiking trail and deposit cool boxes with drinks and food supplies there. Thruhiker speak of “Trail Magic” in all of these cases.

Trail crew volunteers

While the Trail Angels concentrate on caring for and accommodating the Thruhikers, the volunteers, who are grouped in Trail Crews , are dedicated to the expansion and repair of the actual hiking trail; her work benefits all hikers on the Pacific Crest Trail. The Pacific Crest Trail Association recorded a total of 12 trail crews in 2020 , each responsible for different sections of the route. Some of them have descriptive names such as "PCTA Trail Gorillas", "PCTA Lyons' Pride" or "PCTA Can Do Crew". The work of these volunteer groups includes, among other things, clearing the hiking trail of fallen trees and overgrown plants, rebuilding collapsed bridges or restoring sections of the path that have been washed away. As of 2020, eight full-time workers paid by the Pacific Crest Trail Association were working with around 1,500 volunteers to keep the Pacific Crest Trail in good condition.

Well-known hikers and riders

- Martin Papendick: After serving in the US Navy and serving in the Pacific War , Papendick wanted to be the first Thruhiker to hike the Appalachian Trail. While Papendick was still studying geology, Earl Shaffer hiked the Appalachian Trail in one season in 1948. So Papendick turned to the Pacific Crest Trail. His first attempt in 1950 failed, but two years later he hiked from Manning Park to Campo on the Mexican border in 149 days. That is why Papendick is sometimes recognized in the literature as the first thruhiker of the Pacific Crest Trail.

- June and Don Mulford: In 1958, the Washington couple sold their herd of cattle and other possessions to help realize Don's dream of a thruride on the Pacific Crest. With the ten thousand dollars of their proceeds, they bought horses, saddles, bridles, saddlebags, and a 16mm film camera and set off. After five months and a week, they arrived at the Canadian border. Initially, they received a lot of attention for their Thruride and even appeared on television. But then they fell into oblivion until their story was rediscovered in 2009. A copy of the film she made during the trip is available today through the Pacific Crest Trail Association.

- Eric Ryback: As a teenager, Ryback conquered the Appalachian Trail in the summer of 1969 as the 41st Thruhiker. Then, during his senior year at school, he saved money for his attempt to hike the Pacific Crest Trail as well. Ryback began his hike in Manning Park on June 10, 1970, at the age of 19. When he arrived in Campo on October 16, television cameras were already waiting for him. Ryback's 1971 travel and adventure report The High Adventure of Eric Ryback became the first best-seller on the Pacific Crest Trail. His performance was later questioned by Thomas Winnett, publisher of the PCT Guidebook Series , who accused Ryback of hitchhiking part of the way.

- Cheryl Strayed : In her 2012 book Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail , Strayed describes how hiking the PCT in 1995 helped her cope with critical life events such as her recent divorce and her mother's cancer death . The book became an international bestseller, was translated into several languages and finally filmed as The Big Trip - Wild with Reese Witherspoon in the leading role .

Literature and resources

Most of the literature on the Pacific Crest Trail can be roughly divided into experience reports and travel guides with detailed information for hikers. In addition, there is a current selection of maps (as of 2019) for planning and implementing the long-distance hike, as well as some overviews.

Introduction / overview

- Mark Larabee / Barney “Scout” Mann: The Pacific Crest Trail: Exploring America's Wilderness Trail , New York, NY 2016, ISBN 978-0-8478-4976-5 (authoritative overview work, with numerous pictures and graphics as well as detailed chapters on history, Volunteers, Hikers, Literature, etc .; the authors are members of the Pacific Crest Trail Association).

Experience reports (selection)

In English:

- Eric Ryback: The high adventure of Eric Ryback: Canada to Mexico on foot , New York, NY 1978 (first bestseller in the adventure reports category).

- Cheryl Strayed: Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail , New York, NY 2012 (second bestseller in this category; German transl. Der große Trip , Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-442-15812-6 ; for Film see The Big Trip - Wild ).

In German language:

- Andreas Kramer: Pacific Crest Trail: 4,277 km on foot from Mexico to Canada , Welver 2002, ISBN 978-3-86686-123-7 .

- Christine Thürmer: Running. Eat. Schlafen , Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-89029471-1 (report from a German who hiked the Appalachian Trail and the Continental Divide Trail in addition to the PCT).

Travel guide (selection)

The three volumes of the Wilderness Press series have appeared in multiple editions:

- Laura Randall / Ben Schifrin / Jeffrey P. Schaffer: Pacific Crest Trail: Southern California: From the Mexican Border to Tuolumne Meadows , 6th edition, Birmingham, AL 2003, ISBN 978-0899978406 .

- Jordan Summers / Jeffrey P. Schaffer: Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California: From Tuolumne Meadows to the Oregon Border , 6th edition, Birmingham, AL 2003, ISBN 978-0899978420 .

- Jeffrey P. Schaffer / Andrew Selters: Pacific Crest Trail: Oregon and Washington , 7th edition, Birmingham, AL 2012, ISBN 978-0-89997-375-3 .

cards

- National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map - Pacific Crest Trail (created in 2019 in collaboration between National Geographic and the Pacific Crest Trail Association)

- US Forest Service PCT maps (available through the USGS Store )

Web links

- Information from the US Forest Service (English)

- Pacific Crest Trail Association (English)

Remarks

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Jeffrey P. Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , 6th Edition, Birmingham, AL 2003, chapter "The PCT, Its History and Use", pp. 1-6.

- ^ "A high trail winding down the heights of our western mountains with mile markers and shelter huts [...] from the Canadian Border to the Mexican Boundary Line", quoted here from Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , p. 1.

- ↑ Meet the mother of the Pacific Crest Trail: Catherine Montgomery , Pacific Crest Trail Association blog of May 14, 2017, last accessed July 27, 2020 (with pictures).

- ↑ See on this and the following Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , p. 2.

- ↑ See on this and the following Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , p. 2.

- ^ "A continuous wilderness trail across the United States from Canada to Mexico [...] along the summit divides [...], traversing the best scenic areas and maintaining an absolute wilderness character.", Here quoted from Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , P. 2.

- ↑ See on this and the following Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , p. 2f.

- ^ "The mission of the Pacific Crest Trail Association is to protect, preserve and promote the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail as a world-class experience for hikers and equestrians, and for all the values provided by wild and scenic lands.", Pacific Crest Trail Association: Our Mission, Vision and Values , last accessed August 8, 2020.

- ↑ Keith Foskett: The Last Englishman: A 2,640-Mile Hiking Adventure on the Pacific Crest Trail , [no location] [2018], p. 1 and passim .

- ↑ Christine Thürmer: Running. Eat. Schlafen , Munich 2018, p. 9 and passim.

- ^ "The PCT has never been mapped with tools that would provide a truly accurate distance for the trail. What data sets that do exist were generally gathered with consumer level tools and do not take in to account for the various changes that happen every season. Years ago, PCTA decided to settle on a number. We can't re-print t-shirts and remake trail signs every season as the tread moves. The Pacific Crest Trail is around 2,650 miles and that's accurate to within 10 or so miles. ", Pacific Crest Trail Association: Discover the trail - FAQ , section" What's the length of the Pacific Crest Trail? ", Last accessed August 7th 2020.

- ↑ For example Bruce Nelson: Hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. Mexico to Canada , [o. O.] 2018, pp. 47–49, p. 51, p. 186f., And p. 210f.

- ^ "It will be many more years before we are able to break ground for the new trail.", Relocating the PCT to Tejon Ranch on the website of the Pacific Crest Trail Association, last accessed on August 20, 2020.

- ↑ Source: Pacific Crest Trail Overview Map by Andrew Alfred-Duggan based on 2018 data (via the Pacific Crest Trail Association, last accessed August 8, 2020). All numbers and locations here as in the English-language original.

- ↑ "This area may also have the largest concentration of dedicated" trail angels "anywhere along the PCT.", Laura Randall / Ben Schifrin / Jeffrey P. Schaffer: Pacific Crest Trail: Southern California: From the Mexican Border to Tuolumne Meadows , 6 3rd edition, Birmingham, AL 2003, section "Section D: Interstate 15 near Cajon Pass to Agua Dulce", cited here from the Kindle version.

- ↑ For example Nelson, Hiking the Pacific Crest Trail , pp. 149ff., David Smart: The Trail Provides: A Boy's Memoir of Thru-Hiking the Pacific Crest Trail , [o. O.] 2018, p. 197ff., Or Foskett, The Last Englishman , p. 104ff.

- ↑ "The Pacific Crest Trail from the Mt. Whitney Trail junction to Tuolumne Meadows passes through what many backpackers agree is the finest mountain scenery in the United States.", Randall / Schifrin / Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Southern California , section "Section H: Mt. Whitney to Tuolumne Meadows ”, quoted here from the Kindle version.

- ↑ "You sometimes feel you're doing more vertical climbing than horizontal walking.", Schaffer, Pacific Crest Trail: Northern California , section "Section I: Tuolumne Meadows to Sonora Pass", quoted here from the Kindle edition.

- ↑ See COVID-19 and the Pacific Crest Trail on the PCTA website, last accessed on August 16, 2020.

- ↑ Source: PCT Visitor use statistics on the Pacific Crest Trail Association website, last accessed on August 10, 2020.

- ↑ 2,600 miler list on the Pacific Crest Trail Association website, last accessed August 10, 2020.

- ^ For example, Foskett, The Last Englishman , p. 2, and - in somewhat more detail - Gail M. Francis: Bliss (ters). How I walked from Mexico to Canada One Summer , [o. O.] [2015], p. 6f.

- Jump up ↑ As It Happens | Pacific Crest Trail (Andy Laub Films, 2014), Only the Essential: Pacific Crest Trail Documentary (Wild Confluence, 2015), This is not a beautiful hiking video | A Pacific Crest Trail Thru-Hike (Peter Hochhauser, 2017), Pacific Crest Trail Documentary: A Year Of Ice And Fire (Homemade Wanderlust, 2018), 6,270 kms - A Pacific Crest Trail Documentary (Anthony Jouannic, 2018), It Is The People | A Pacific Crest Trail Film (Elina Osborne, 2019)

- ↑ Tell It On the Mountain - Tales from the Pacific Crest Trail , director: Lisa Diener, from minute 2:44 to 2:59.

- ↑ For example, Christine Thürmer, Laufen. Eat. Schlafen , Munich 2018, pp. 26–33.

- ↑ See the Winter recreation and snow information on the website of the Pacific Crest Trail Association, last accessed on August 16, 2020.

- ↑ See, for example, Nelson, Hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. Mexico to Canada , pp. 94f.

- ↑ Foskett, The Last Englishman , p. 110, notes on this: “Some regard mountains as intimidating. If it goes wrong, you're in trouble. There's no quick medical help in the Sierras; not even phone reception to make the call. To many, this intimidation is precisely the attraction. "

- ↑ Thürmer, Laufen. Eat. Sleep , p. 54f.

- ↑ Ray Jardine: The PCT Hiker's Handbook: innovative techniques and trail tested instruction for the long distance backpacker , LaPine 1992, since 1999 under the title Beyond Backpacking: Ray Jardines Guide to Lightweight Hiking , LaPine 1999.

- ↑ a b “Pure thru rides are attempted once every few years. Historically, only a handful of thru-riders have successfully completed the trail. ", Equestrian FAQ on the Pacific Crest Trail Association website, last accessed on August 17, 2020.

- ↑ The Pacific Crest Trail Association writes: "Riding the Pacific Crest Trail requires an immense amount of research - much more than the hikers need to do. Your research will happen not just at home, but while you're on the trail too. ", Equestrian basics on the PCTA website, last accessed on August 17, 2020.

- ↑ Equestrian logistics on the Pacific Crest Trail Association website, last accessed on August 17, 2020.

- ^ "The PCT is spectacular, and the path is usually quite safe for horses. But parts of it can also be tough and unforgiving - don't underestimate the trail, or overestimate your ability or your horse's capability to travel on it. ", Equestrian safety on the website of the Pacific Crest Trail Association, last accessed on August 17th 2020.

- ↑ For the Trail Angels cf. also Mark Larabee / Barney Scout Mann: The Pacific Crest Trail: Exploring America's Wilderness Trail , New York, NY 2016, pp. 74-80.

- ↑ For the trail crews cf. also Larabee / Mann, The Pacific Crest Trail , pp. 120-125, and pp. 13f.

- ↑ Regional groups on the Pacific Crest Trail Association website, last accessed August 10, 2020.

- ^ Trail maintenance and reconstruction on the Pacific Trail Association website, last accessed August 10, 2020.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Larabee / Mann, The Pacific Crest Trail , p. 46.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Larabee / Mann, The Pacific Crest Trail , pp. 49-52.

- ↑ In addition, Barnie “Scout” Mann, Giving Trail History Its Due: The 1959 PCT Thru-Ride of Don and June Mulford , in: PCT Communicator, December 2019, pp. 12-16.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Larabee / Mann, The Pacific Crest Trail , pp. 63-64.

- ↑ See on this aspect the section “The Winnett Caper” in Larabee / Mann, The Pacific Crest Trail , pp. 68-71.

- ↑ a b According to Larabee / Mann, The Pacific Crest Trail , p. 70, Ryback's and Strayed's report were the two bestsellers in this category. The third bestseller was The Pacific Crest Trail , published by National Geographic .