Navajo (people)

The Navajo , also known as Navaho or Diné , are the second largest of the Native American peoples in the United States with around 332,100 tribesmen . If you compare them with other tribes, they make up the largest proportion of the number of those who identified themselves exclusively with a single tribal affiliation in the US census of 2010 and not at the same time with other tribal groups or the ethnicities or affiliations queried there.

The Navajo are dispersed in northwestern New Mexico , northeastern Arizona , southeastern Utah, and other parts of the United States. In northeast Arizona lies the Navajo Nation Reservation , which extends into New Mexico and Utah, both in terms of population and in terms of area, the largest reservation in the United States, in which a little more than half of all Navajo live.

Origin of name

Diné is her own name and means “people of the people” or literally, based on her myths, “people emerging from below the earth”. They therefore also called themselves Nihookááʼ Dineʼé (natural people, earth people). Non-Navajo tribes and strangers referred to them as Ana'ii or Anaa'i (strangers, enemies). The name Navaho comes from the Tewa language. Navahuu denotes a cultivated field there because the Navajo, in contrast to the nomadic Apaches related to them, were excellent farmers. The Spaniards called them Apaches de Navahu ("Apaches of the planted land"). Their language is also called Navajo (own name Diné bizaad ) and belongs to the Na-Dené language family .

In addition to the actual Navajo, a larger group of families split off from around 1750 (the Cañoncito Navajo, named after their main settlement area, also lived in the Cebolleta Mountains), and those south and east of the actual tribal area (i.e. outside Dinetah ) in permanent settlements lived near the Pueblo and Spaniards, practiced agriculture and mostly adopted Christianity. But what ultimately alienated them from the Navajo was their active participation as scouts in the campaigns of the Spaniards (later Mexicans and Americans) against free roving and independent Navajo. The Navajo called them Diné Ana'ii or Diné Anaa'i (pronounced: Di-neh Aw-naw-uh, Alien or Enemy Navajo, i.e. foreign or hostile Navajo).

The Apaches related to them called the Navajo Yúdahá (= “Live Far Up”, “Those who live [far up] in the north”) and the Diné Ana'ii Ndá Yúdahá (= “Enemy Navajo”, hostile Navajo or “White Man Navajo ", Navajo of the white man). In addition, escaped Navajo slaves from Socorro , who settled in Alamo (= "at Field's Place"), 35 miles northwest of Magdalena , became the so-called Alamo Navajo or Puertocito Navajo . They probably originally formed a group of the Diné Ana'ii and were commonly called Tsa Dei'alth (= "stone chewers", "those who chew stones") because they allegedly got so angry during the fight that they chewed stones . Some Chiricahua and Mescalero families and some Mexicans also joined them. Later, some Navajo fled the pursuit of Kit Carson or Fort Sumner, the Mescalero reservation on the Rio Pecos, and found shelter with the Puertocito-Navajo.

residential area

The Navajo Nation Reserve and the government-assigned land in the southwestern United States today covers a total of more than 69,000 km² and is in part a tourist attraction. Best known are Monument Valley and Canyon de Chelly .

Thousands of Navajo earn their living working far away from Navajo Land, and significant numbers have settled on irrigated land on the Colorado River and in cities like Los Angeles and Kansas City .

history

When the Navajo and the Apaches from Canada moved to the southwest is the subject of research and the details are not clear. In the sub-arctic regions of Canada all the other Athabasque-speaking Indian tribes still live today. A plausible assumption is that the ancestors of today's Navajo moved to the Interior Plateau of today's British Columbia between 1000 and 1200 . From there they would have moved south in several waves and in small groups on the eastern flank of the Rocky Mountains and arrived in the southwest around 1450 . They took over elements from the local Pueblo Indians' culture, which was adapted to the region, and split them up into three geographically and culturally different subgroups within a short period of time. The prairie would have been settled by the Kiowa , who changed their culture through access to horses in the 16th century. Today's Navajo would have spread westward and become more sedentary, later they would have started to farm. And the Apaches would have remained more mobile and opened up the southern mountains for themselves. An alternative theory is that the Proto-Navajo would have moved south across the High Desert and the Great Basin and spread to the east. Sections of the Navajo and Apaches deny that their ancestors ever settled in other regions and assume in their creation myths that they were the original humans who were created in the areas where they live today.

The prevailing view is that the Navajo reached the easternmost part of their present-day settlement area Dinétah in New Mexico around 1550 and settled there for several centuries before slowly expanding westward from around 1750. According to the scientific discussion, this spread could have happened a little earlier, so that the western regions of today's settlement area in Arizona would have been reached well before 1800.

Dendrochronological studies of tree rings from Navajo buildings could be assigned to such an extent that the spread can be dated more precisely. Accordingly, the vast majority of finds are too young or too vague to make a statement about the extent of the disease. However, a small number of dates allows the history of the settlement to be narrowed down. According to this, a spread in a westerly direction can be proven: Around 1750 they reached the upper reaches of the Little Colorado River in northeastern Arizona and built a fortified system there, so that they probably forcibly penetrated the inhabited area. The Black Mesa was reached around 1840, the region north and east of the Hopi settlement areas in the 1850s and the land west of the Hopi only after 1870, after the return from the Long March , the temporary forced relocation to Fort Sumner .

Contacts between the Navajo and Pueblo Indians are documented from at least the 17th century, when refugees from some Rio Grande Pueblos came to the Navajo after the Spanish suppression of the Pueblo uprising . In the 18th century, due to drought and famine , some Hopi left their mesas to live with the Navajo, especially in Canyon de Chelly in northeastern Arizona. Under this Pueblo influence, agriculture became the most important basis of their subsistence with the simultaneous development of a sedentary way of life. In historical times, after contact with the Spaniards, agriculture was supplemented by keeping sheep, goats, horses and cattle, and in some areas even completely replaced by it. The Apache de Navahu were first mentioned in Spanish reports from 1626 and thus differentiated from the Apaches.

Spanish and Mexican Period (1535 to 1848)

Like the Apaches, the Navajo attacked pueblos and Spanish settlements, especially to steal sheep and horses, and so they developed a new form of farming based on agriculture, livestock and prey. In addition, from 1650 on, slaves were captured and sold in the markets in New Mexico by the Navajo and various Plains tribes. Particularly preferred victims were the Pawnee in the east and the peaceful southern Paiute in the north. Due to their marginal living conditions, the southern Paiute could hardly build up any supplies, so that they came through the winter only emaciated and often half starved. That is why the Navajo and Apaches always went on Paiute slave hunting in spring, as they were then particularly easy and defenseless victims. Often they had to be supplied with food again for the first time so that they could achieve good prices on the markets. Since the Navajo could well feed additional eaters thanks to their broad economic base and also needed helpers for tending the sheep and horses as well as for the lower chores in the household, the Navajo often kept slaves. The mostly nomadic Apaches, on the other hand, did not have a great need for slaves and therefore usually sold prisoners immediately on the markets. When the Spaniards initially withdrew from large parts of New Mexico after the Pueblo Uprising of 1680, they left parts of their herds behind. These animals, along with those captured in raids, laid the foundation for the large Navajo herds of cattle. Sheep became the basis of an extensive tradition of weaving woolen fabrics, and especially blankets.

When the Comanche and their allies, the Ute , appeared in the east and north of Dinetah, the pressure of enemy raids on the now wealthy Navajo with their flocks of sheep, fields, herds of horses and their coveted Navajo blankets increased enormously. The Navajo had to withdraw further and further west and hide deep in the canyons because of the ongoing raids by the newly emerged enemies. The Navajo soon referred to the enemies coming from the east and north on fast Mustangs as Ana'i ("foreigners = enemies"), and the Ute in particular would later become the nemesis of the Navajo. The Ana'i were later joined by the Kiowa , Kiowa-Apache, and Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho . Even with their Athabaskan relatives in the east and northeast, the the Great Plains living Beehai ( "Winter Folk" - Jicarilla Apache ), Naashgali Dine'i ( Naashgal Dine '? - "people close to the mountains" - "people, that lives near the mountains ”- Mescalero Apache ) and Tsétát'ah Chishí ( Lipan Apache ), the Navajo lived in open hostility. Only with the Dziłghą́'í ( Western Apache ) and the Chíshí ( Chiricahua Apache ) did the Navajo usually have a friendly relationship and were often their allies in joint raids in northern Mexico. Although the Navajo were well aware of their relationship to the various Apache peoples, they did not consider them to be Navajo themselves.

After 1770, for their part, the Navajo were bloodily suppressed by the Spanish. A long and bitter period of territorial encroachment and the capture of Indian slaves began. In 1786 - the Spaniards had just formed an alliance with the Ute, Comanche and their allies, the Norteños - the Navajo were forced to give up their alliance with the Apaches and fight them together with the Spaniards. Should the Navajo refuse, the Comanche threatened to wipe them out. The eastern groups (or clans) in particular had to fight the Apaches under the pressure of the united hostile tribes, but the western groups were mostly able to retreat into the canyons and hide.

In 1804 the Navajo attacked the Naakaii (Spaniards, later also Mexicans) and were bloody repulsed at Canyon de Chelly. A dark chapter is the enslavement of many Navajo, which was practiced by Spaniards and Mexicans. Young Indians were captured and forced to work in Mexican silver mines in inhumane conditions.

History in the 19th century

When the United States government annexed the territory of the Navajo in 1849, they were feared as a number of belligerent and aggressive groups. For many years the government tried in vain to stop the forays to allow American and Mexican farmers to settle.

In 1851, Fort Defiance was the first American military post to be established in Navajo land. During the American Civil War , the Washington government wanted the territories of Arizona and New Mexico to remain in the Union. This should keep the traffic routes and communication links to and from California open. Therefore the raids had to be stopped mainly by the Mescalero and Navajo. The Mescalero were relocated to Fort Sumner or Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River in 1862 . This place lacked firewood, drinkable water and good arable land.

In the summer of 1863, Colonel Christopher Carson (Kit Carson) was commissioned by Commander-in-Chief General James Carleton to drive the Navajo into the new military Indian reservation on the Pecos River. The military sent negotiators to some Navajo groups and local leaders asking them to move to Bosque Redondo, otherwise they would be forced to do so. Most of the dispersed Navajo people never heard of this ultimatum, and General Carleton made no attempt to track it down. Instead, he ordered Kit Carson to destroy the Navajo's economic foundations. Carson went with 300 soldiers, reinforced by Ute , Pueblo Indians, and New Mexico militants, through the Navajo lands, destroying orchards, stocks of corn, hogans , watering holes, and herds of cattle. On January 14, 1864, the actual campaign began. Kit Carson gave the Navajo the apparent refuge of taking refuge with their main force in the Canyon de Chelly, which they considered impregnable. But the Americans had positioned cannons on the edges of the ravine and the Navajo surrendered after a brief engagement. On January 23, 1864, Kit Carson reported to General Carleton:

“I tried to make them understand that resistance is pointless. They said they only started the war because the strategy of extermination was proclaimed. They would have made peace and accepted a reservation long before that if they had known they were being treated fairly. I report that there were unfortunately 23 deaths on your side. I gave them meat and allowed them to return to their pastures. There they are supposed to tell their members of the tribe who are hiding that I am expecting them all here at Fort Canby to move with them to the Bosque Redondo reservation. "

The long march

Few of the Navajo escaped under the leadership of Chief Manuelito . Livelihoods were ruined, and in February 1864 over 8,000 Navajo rallied at Fort Defiance, now called Fort Canby . They were on the Long March (Engl. Long Walk ) sent to Fort Sumner. The project ended in disaster and cost a total of about a quarter of the Indians' lives. General William T. Sherman led a delegation of inquiry and was shocked by the conditions. On June 1, 1868, a treaty was signed that gave the Navajo a part of the old homeland as a reservation and allowed them to return.

History in the 20th century

In the early 20th century, the reserve was enlarged and living conditions improved. The Navajo are famous for their craftsmanship as weavers and silversmiths. They experienced a period of relative prosperity and the number of tribesmen grew. This also increased the number of cattle herds, so that the ecologically fragile land was overgrazed and soil erosion became rampant. In the 1930s, the US government ordered livestock cuts and many animals killed - a disaster for the Navajo when their livelihoods were destroyed before their very eyes.

The Navajo had a long dispute over land with their neighbors, the Hopi . The Hopi, whose pueblos on the mesas are completely enclosed by the Navajo reservation, accused the Navajo for years of stealing cattle and crops. Tensions peaked in 1974 when Congress passed a law that redistributed a large piece of land between the tribes. As a result, 11,000 Navajo and 100 Hopi had to leave their homes and move to government-provided apartments.

During the Second World War , relatively many Navajo worked as radio operators for the US military in the Pacific War against Japan . When the Japanese succeeded in deciphering American radio codes, the Navajo code was developed, which essentially consisted of the Navajo language. This was only supplemented by a few code words that denoted military-technical things and for which there were no Navajo words. Navajo known as the Windtalkers were deployed in all locations of the Pacific War and exchanged messages in their language. This radio communication could not be translated by the Japanese despite their best efforts until the end of the war - an advantage of the extraordinarily complex language of the Navajo. The Windtalkers received comparatively high recognition from the US Army, but many details of this operation were not known until decades later because of the secrecy. August 14th has been declared National Navajo Code Speakers Day in commemoration . During the Cold War , the Soviet Union also set up a language course in Navajo at Moscow's Lomonosov University .

Current situation

With nearly 300,000 tribesmen, the Navajo are now the most populous tribe in North America. The nation since 1923 by a tribal council, composed of the representatives of the 88 settlements, and a directly elected Chairman (Engl. Chairman ) managed. It has tax sovereignty like an American state, its own police force and its own jurisdiction . The median age of the Navajo people is 18 and the birth rate is 2.7%. The reserve's soil is rich in raw materials such as oil, natural gas, coal, wood and uranium, which, while generating money, also pose problems such as increasing environmental degradation, health hazards and forced relocation ordered by the US government. Despite all the raw materials, there are far too few processing companies and no service industry of their own. As in the other reservations, the unemployment rate is high, it is 40 percent, and poverty is depressing - although the Navajo have the highest incomes of any Indian tribe in the United States. The Diné College (Diné University) and the Center for Diné Teacher Education are now in Tsaile , AZ, near the Canyon de Chelly.

Since the turn of the millennium there have been increasing attempts to preserve traditional culture, which is expressed in language programs, but also in increasing interest in medicine men. Young Navajo are now the last generation of children who went to boarding schools with their re-education programs. In the second decade of the 21st century, there was increasing fear that the Navajo language would become extinct. While at the end of the Second World War almost every resident of the Navajo reservation still spoke Navajo as their mother tongue, 70 years later only a few young Navajo spoke the language of their grandparents. In 1998, 30 percent of Navajo people spoke Navajo as their mother tongue when they started school, compared to around 90 percent 30 years earlier. On the reservation, Navajo language classes start at a young age. At Indian Wells Elementary School , opened in 2001, third graders learn to read, write and speak in Navajo. The school association Holbrook Unified School District claims to see it as its duty to preserve the Navajo language.

Way of life and culture

The life of the Navajo takes place in and around their Hogans . Traditional Navajo houses are windowless, built of wood, brushwood, and mud, and the entrance faces the rising sun. The fireplace is in the middle of a depression in the ground and the smoke can escape through a hole in the roof. In the Hogan it is cool in summer and comfortably warm in winter. At night the residents lie around the fireplace like the spokes of a wheel. There are also modern hogans, octagonal log cabins with a domed roof from which the chimney protrudes. They are more spacious than the old-style Hogans, but built according to the same basic structure. If a Navajo used to die, a hole was knocked in the back of the hogan through which the corpse was carried out. Then the relatives burned the house and all belongings, the place was avoided for fear of the ghosts of the dead.

Social organization

The Navajo are also similar to the Apache peoples in that they do without central tribal or political organization. They used to be in local groups (Engl. Outfits or Local Bands of related) clans or extended families (Engl. Extended Family split), each with a local chief. Similar groups still exist today, but they stick together more because of residency than consanguinity, and many of these local groups have elected leaders. A local group does not correspond to a village or city, but rather to a collection of properties of 10 to 40 families scattered over a large area.

The Navajo are divided into more than 50 clans . The Navajo family structure is matrilineal , which means that the relationships are determined by the female line. In addition, the clans are also matrilocally organized, so that the man moved to his wife's family and their settlement at the wedding. Members of a clan are not allowed to marry within their own clan. The basis of the social structure is the extended family, whereby the individual members have fixed obligations.

The names of more than half of the clans suggest that they were derived from the places where the clan originated. One of the original four clans, the Kinyaa'aanii (Towering House Clan), originated in a pueblo ruin in New Mexico, and the Deeshchii'nii (Start-Of-The-Red-Streaked People) came from a canyon in Land of the Cibecue Apache, a group of the Western Apaches - consequently the Cibecue Apache were later adopted by this clan as T'iisch'ebaanii (Gray-Cottonwood-Extend-Out People) . The remaining clans derived their origins from other tribes including Mexicans. There were the Nóóda'i Diné (Ute), Naaɫani Diné ( Many Comanche Warriors Clan, Comanche), Naakétɫ'ahi (Flatfoot People, Akimel O'Odham ) and several adopted Pueblo clans ( Zuñi , Jemez , Zia , Santa Ana , Tewa and Hopi ).

Political organization

Naataanii (male and female traditional leaders)

During the Hispanic-Mexican rule there were five loose political geographical groupings of the Navajo. These were located at Mount Taylor , Cebolleta (settlement area of the Diné Ana'ii, Enemy Navajo ), Chuska Mountains , Bear Springs and Canyon de Chelly . The individual local groups each elected two chiefs , the Naataanii - one for war and one for peace.

The Peace Naataanii were chosen for their excellent morals, their ritual knowledge of hosting the Blessing Way ceremony, their great rhetoric, their charisma, their prestige and often for their wealth of sheep and horses. Traditionally, they performed their duty and responsibility for the community throughout their lives, but were expected to resign shortly before their death and propose a successor to the local group as leader. Sometimes women were also elected to Peace Naataanii, because they owned the houses and herds of cattle in Navajo society and thus had enormous economic and political influence. The Peace Naataanii decided on the economic development (agriculture, gathering, trade) of the local group (or clan), the choice of pasture places for the herds and the hunting grounds. In addition, they had to mediate in family disputes, deal with witchcraft ( chindi - "human wolves", sorcerers) and diplomatically represent their local group vis-à-vis other Navajo as well as neighboring tribes (and later Spaniards and Americans) - thus they also had the decision about war or to make peace.

In order to achieve the position of war Naataanii, however, one had to have enormous ritual knowledge of one or even several war ways or enemy ways - these war ways were ceremonies that were aimed at ritually forcing successful raids or retaliation. The Navajo had an ambivalent attitude towards the war Naataanii. Although they respected them as great warriors and leaders, they were often criticized - be it because the war Naataanii had become too arbitrary or a campaign had been a failure.

Both Peace Naataanii and War Naataanii were advised and supported in their daily tasks and duties by Hastól (older men) and Hataoli / Hataali (holy men and women). In addition, these men and women established the important connection between the Naataanii and the Diyin Diné (Holy People), which was existentially important for the community.

Naachid - traditional gatherings (approx. 1650 to approx. 1860)

There were regular meetings (every two or four years, every year in tribal crises) of several local groups, which were held for political as well as for ceremonial and religious reasons. During these Naachid (= to gesture with the hand) 24 Naataanii - twelve for peace and twelve for war - met in a special hogan to discuss all matters. At these Naachid the Naataanii often gathered to hold ceremonies and rituals for sufficient water, fertility of the arable land and - in case of danger from enemies - for success in war. Therefore, the Naachid often served the Navajo as a war and peace council, in which it was decided whether to enter into negotiations with enemies or retaliate. During peacetime the Peace Naatannii presided. But if war broke out or if there was danger from enemies outside Dinétah, the war Naataanii took control of the Naachid . Women could speak openly in front of the congregation if they had participated in wars, raids or otherwise held a high status.

The decisions of the Naachid were not binding on the participating local groups, nor on those groups that did not participate. The Naachid made it possible for the Navajo in times of war or economic hardship when it was necessary to assemble as many local groups as possible and come to a common decision. In the last great Naachid, in 1840, the Navajo gathered and decided that they would make peace with the Mexicans in Santa Fe. The last recorded Naachid took place during the war against the Americans in the years 1850-1860 , after which the Navajo were no longer able to continue these traditional political gatherings. The various local groups as well as individual families and war groups were constantly on the run from the American army, desperately looking for shelter and food, so that there was no time for larger gatherings of several local groups and Naataanii.

Crafts and arts

The Pueblo Indians influenced the Navajo not only in agriculture, but also in art. Painted pottery and the famous Navajo bridges as well as elements of Navajo ceremonies such as dry sand painting are the result of these contacts. Another excellent Navajo handicraft, silversmithing, dates back to the mid-19th century and was probably first introduced to the tribe by Mexican silversmiths.

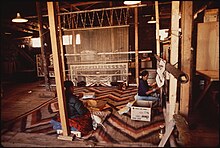

Religious symbolism also influenced Navajo art. Wherever a Navajo woman is, the loom cannot be far. First they made patterned woven blankets that were worn as ponchos . However, the famous Navajo carpet is the invention of white traders from the era of railroad construction and the first tourists. The guests from the east could not do much with the blankets, so they were renamed and called carpets ( rugs ) and laid the foundation for a new line of business. Even the children are extremely skilled in playing thread games , as a preliminary stage in handling the loom. Ethnologists have therefore devoted a new expression to them: If a lower loop is to be brought over an upper one while playing the thread on one finger, one says: "Do a Navajo!"

In the last 50 years the Navajo sand pictures (Engl. Dry Paintings ) have come to the public from the semi-darkness of the Hogans. The origin of this painting technique is unclear. The pictures are traditionally made during night healing ceremonies in Hogans. The artists are specially trained medicine men who have acquired complicated prayers, chants and painting techniques over the years. The pictures are 60 to 90 cm in diameter and are made of colored rock powder, corn pollen and other sacred materials. The motifs are images of the Navajo gods who are implored to heal the patient during the ceremony. Just before dawn, the ceremony ends and the sacred images are destroyed. The collected sand is buried north of the Hogans. Today they also make long-lasting sand paintings for commercial purposes. In addition to the above-mentioned motifs, they also show landscapes, portraits of Indians, pottery and weaving patterns and abstract forms. There are hundreds of such artists on the reservation - the best work in the Shiprock area of New Mexico. Work since the 1890s and artisan workshops can be viewed at various locations on the reservation, most notably at the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site in Ganado , Arizona .

Believe

The religious traditions and rites of the Navajo are diverse, animistic (all-soulfulness) and polytheistic (polytheistic). What they have in common is a reference to landmarks and specific locations. The Navajo worldview is based primarily on Hózhó (“beauty” or “harmony”), a spiritual ideal state that everything revolves around preserving.

The pantheon of gods is extremely diverse. The ethnologist Gladys Reichard tried to classify the world of gods in order to better understand the diversity: She created categories such as the “talkable deities” - who only do good; the "untrustworthy deities" - to whom one has to sacrifice a lot in order to obtain their help; the "beings between good and evil" such as cold, sleep and need - who look cruel but are mild; the "insubstantial deities" - who only do evil and must be kept away; the diyin people - who mediate between humans and gods; and the cultural heroes - like the twin war gods. The Diyin Diné are the (mythical) "holy people" who move with the wind, on a ray of sunshine or a clap of thunder. Reichard suspects that behind all gods and spirits hides the (masculine) sun as the highest driving force in the universe. As an unnamed and mysterious force, it takes the place of a “ high god ” whose work is revealed everywhere in creation.

Some of the many myths relate to the creation of the first humans from different worlds beneath the surface of the earth; other stories explain the countless common rites . Some of these are simple rituals celebrated by individuals or families that are said to bring luck to travel, business, and gaming, as well as protection for the harvest and the flocks. These were, for example, offerings of tobacco, cornmeal or pollen. The more complex rites require a specialist who is paid for according to their ability and the length of the ceremonies. Most of the rites are organized primarily to heal physical or mental illnesses. Other ceremonies have simple prayers and chants and sand pictures are made. In some cases there are public dances and performances that gather hundreds or thousands of Navajo and tourists.

Two particularly important deities are Asdzáá Nádleehé ( Changing Woman ) and Mother Earth, who is beautiful, always young and generous and who watches over the welfare of the people. When she was a baby, she was found by Altsé Hastiin (first husband) and Altsé Asdzaa (first wife). The baby lay in a cradle created by gods on a sacred mountain and within four days, Changing Woman grew into a mature woman. It was she who taught the Navajo how to live their lives in harmony with nature. The life-giving, life-sustaining and childbearing roles of Changing Woman are also reflected in the social organization of the Navajo: women dominated social and economic affairs, the clans were matrilineal and matrilocally organized, and both the land and the sheep were owned by the women of the Local groups controlled. Changing Woman, according to one version of the myth, was the child of Sa'ah Naaghaii (first boy), who symbolizes the spirit (the mind), and of Bik'eh H-zh (first girl), who embodies language. Together, Sa'ah Naaghaii and Bik'eh H-zh figuratively represented the ideal world of the Navajo and contained their most important ideas and values.

In addition, the Navajo believed that every living being had an inner and an outer shape that had to be brought into harmony and balance again and again. Therefore the inner form had to unite with Sa'ah Naaghaii (first boy) and the outer form had to try the same with Bik'eh H-zh (first girl). Changing Woman represented a synthesis of the two, and therefore had the strength, the immortality of all life and all living things through perpetual reproduction (change = Changing ) to achieve. The belief in animal guardian spirits, on the other hand, which was otherwise found almost everywhere in North America, was not found among the Navajo.

The Christian mission had minimal influence until the beginning of the 20th century. Christianization was not successful until the 1920s . In the 1970s, many tribal members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) were converted. For many Navajo people, everyday life and religion are inseparable. Even today the men go to the fields and sing so that the maize can grow. The weavers draw a special thread into their carpets as a spiritual path . According to the ongoing surveys by the evangelical-fundamentalist conversion network Joshua Project , 25 percent of the Navajo still profess the traditional religion , 60 percent are (officially) Christians (mostly Protestants) and 15 percent describe themselves as non-religious.

Creation myth (Diné bahane ')

The Navajo believed in the existence of four consecutive worlds - the First World / Black World (also: Red World , which corresponded to the Underworld ), the Second World / Blue World (Niʼ Hodootłʼizh) and the Third World / Yellow World (Niʼ Hałtsooí) were not inhabited by humans, but only by the Diyin Dine'e / Holy People (spirit beings who gave the morality and laws to animals and humans) and gods as well as by four living beings or animal species , also called Diné ("people") , these animal species each inhabited one of these worlds, and since they followed the gods and the holy people on their wandering through the worlds to the last - the Fourth World / White World (Niʼ Hodisxǫs) - all animal creatures lived in this last world - the Ch'osh Dine '/ insects , the Naat'agii Dine'e / birds (literally: "flying animals / people"), the Naaldlooshii Dine'e / four-legged animals (literally: "four-legged people") and the Ta [t] '11h Dine'e / Underwater Ti ere (literally: "underwater people") already there, when the Navajo and the other peoples of men were last created in this. Since for the Navajo all living beings were also Diné , they were treated as relatives and with great respect. The world today (after the arrival of the Europeans) is therefore sometimes referred to by the Navajo as the Fifth World .

The religion and cosmology of the Navajo are strongly characterized by a positive dualism or polarity and therefore their traditional country Dinétah (“among the Navajo / the people, in the territory of the Navajo / the people”; from Diné - “Navajo "Or" people ", -tah -" under, through, in the area of ") between the protective parents, the earth (or nature ) personified as mother, called Nihi Má Ni'asdzáán / Mother Earth (also: Nahasdzáán ) and Nihi Zhé'e Yádiłhił / Father Heaven (also: Yádiłhił or Yadilyil ).

In addition, the number four is of particular importance for Apaches and Navajo and, according to their tradition, is full of positive magic, symbolism and holiness:

- four consecutive worlds:

- the first world / black world (also: red world )

- the second world / blue world (Niʼ Hodootłʼizh)

- the Third World / Yellow World (Niʼ Hałtsooí) and

- the fourth world / white world (Niʼ Hodisxǫs)

- the four living beings or animal species

- the four original Doone'e / clans of the Navajo, which were joined by new ones due to the growing Navajo population, and foreign peoples were adopted as clans and thus integrated into the Navajo nation (e.g. the Pima as Naaket l 'ahi - "Flat foot People Clan" , the Ute as Nooda'i dine'e - "Ute Clan" , the Cibecue Apache as T'iisch'ebaanii - "Gray Cottenwood Extending out Clan" or the Mescalero Apache as Naashgali dine' e ).

- Towering House Clan / Kinyaa'aanii / Kiyaa'aanii

- One Walks Around (You) Clan / Honaghaahnii / Honághááhnii

- Mud (People) Clan / Hashtl'ishnii

- Bitter Water Clan / Todich'ii'nii / Tó dích'íinii

- the four Dził since diyinigii / Four Sacred Mountains ( Four Sacred Mountains ) limit geographically and cultic Dinétah:

- the holy mountain in the east: Blanca Peak / Sis Naajiní , also: Tsisnaajini, Sis na'jin - “Dawn” or “White Shell Mountain”, with 4,374 m the highest peak of the Sangre de Cristo Range in southern Colorado

- the holy mountain in the south: Mount Taylor / Tsoodził - "Blue Bead", also: Dootł'izhii Dził - " turquoise colored mountain", with 3,446 m highest peak of the San Mateo Mountains in northwest New Mexico

- the holy mountain in the west: the San Francisco Peaks / Dookʼoʼoosłííd - “Abalone Shell Mountain” - “Mountain of Abalone Shells ”, north of the city of Flagstaff in Arizona

- the holy mountain in the north: Hesperus Mountain / Dibé Nitsaa - “Big Mountain Sheep” or “Obsidian Mountain”, with 4,035 m the highest peak of the La Plata Mountains, a mountain range of the San Juan Mountains in the southwest of Colorado

- the four main directions :

- the four sacred cultivated plants :

- the white and yellow maize represent the north

- the beans represent the east, both are masculine for the Navajo

- the squash (pumpkin) stands for the south and

- the tobacco stands for the West, both are feminine for the Navajo

- the four sacred colors associated with the respective cardinal points, sacred mountains and sacred plants:

- Łigai / White - represents the Fourth World, the East, Blanca Peak and the beans

- Dootł'izh / turquoise (also for blue and green ) - represents the second world, the south, Mount Taylor and squash (pumpkin)

- Łitso / Yellow - represents the Third World, the West, the San Francisco Peaks as well as tobacco and

- Łizhin / Schwarz - represents the First World, the North, Hesperus Mountain and maize.

The Navajo believe in the origin of an underworld, which they call the First World (or Black World ). This timeless place was known only to the spirit beings and the holy people (Diyin Diné) . The first man and first woman lived here, separated in the east and west . When First Man burned a crystal and First Woman did the same with a turquoise, they saw each other's fire and were united. But soon the beings of the First World began arguing and wreaking havoc. In doing so, they forced the First Man and First Woman to move east. Both led the way first into the Blue World and then into the Yellow world in which they the six sacred mountains (Engl. Sacred Mountains found) that are up to the present revered as sacred. These Sacred Mountains are in the east the Blanca Peak (Sis Naajiní, Tsisnaajini, Sis na'jin) in Colorado , in the west the San Francisco Peaks (Dook'o'oslííd) in Arizona , in the north Hesperus Mountain (Dibé Ntsaa) in the La Plata Mountains, also in Colorado; in the south it is Mount Taylor ( Tsoodzil ) in New Mexico . In this area is also the Huerfano Mesa ( Dził Ná'oodiłii , “Soft Goods Mountain” or “Banded Rock Mountain”), in which Changing Woman / Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé (in older sources also: Ahsonnutli, Estsanatlehi or Etsanatlehi ) was raised and the central holy mountain, the Gobernador Knob ( Chʼóol'į́ʼí , “Precious Stones Mountains” or “Great Spruce Mountain”) . According to tradition, Coyote caused unrest in the Yellow World by stealing the child from Water Monster , and the latter made the whole world sink into the water full of anger. But First Man planted a plant that grew high in the sky, and on it the living things could escape the floods. When the waters receded, the found First Men (Engl. First People in the radiant) Fifth World again, today's Land of the Navajo, the Dinétah .

According to another tradition, Changing Woman / Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé gave birth to the twins Naayéé 'Neezgháni ( Monster Slayer ) and Tó Bájish Chini ( Child Born of Water ), who killed all the monsters. Thereupon Changing Woman hiked with her husband, Father Heaven, west to the Pacific together with some people (back then these were still talking animals), so that she might not feel alone. But after a while the animals returned east to their old homeland Dinétah when they heard that some of them were still living there. As a result, Changing Woman decided that there should be more living beings (this time they are humans, Navajo) in Dinétah and created the first four clans. Changing Woman rubbed the skin off her chest and created the Kinyaa'aanii (Towering House Clan), from the rubbed skin on her back she created the Honaghaanii (One-Walk-Around Clan), and the Todich emerged from the skin under her right arm 'ii'nii (Bitter Water Clan) and from the one under her left arm the Hashtl'ishnii (Mud Clan) .

As people moved through Dinétah, they also adopted neighboring tribes as clans in their tribal organization (in fact almost all neighboring peoples are represented as clans in the Navajo). The Beiyóódzine Diné ( Southern Paiute ) who lived around Navajo Mountain ( Naatsis'áán ) were adopted but later left behind due to religious differences. The Navajo then moved further south, leaving the Chishi (Chiricahua Apache) behind and adopting the Naakaii Diné (Mexicans). They then turned to the east, where the Naashgali Diné (Mescalero Apache) decided to stay. Now they migrated to Dibé Ntsaa in the La Plata Mountains, whereupon they settled there for seven years, but the summers were too short for growing corn and pumpkins - so most of the Navajo left the area and moved to Cabezon Peak (Tsé Naajiin) . The ones that stayed behind were the beehai (Jicarilla Apache).

Chiefs and leaders

Demographics

| year | source | number | Remarks | |

| 1680 | James Mooney | 8,000 | estimated | |

| 1867 | unknown | 7,300 | ||

| 1890 | census | 17.204 | flawed | |

| 1900 | census | 19,000 | flawed | |

| 1910 | census | 22,455 | ||

| 1923 | US Indian Office | 30,000 | estimated | |

| 1930 | census | 39,064 | ||

| 1937 | US Indian Office | 44,304 | ||

| 2000 | census | 269,000 | ||

| 2010 | census | 332.129 |

See also

literature

- William C. Sturtevant (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC

- Alfonso Ortiz (Ed.): Southwest. Vol. 9. 1979, ISBN 0-16-004577-0 .

- Alfonso Ortiz (Ed.): Southwest. Vol. 10. 1983, ISBN 0-16-004579-7 .

- Martina Müller: "Sand pictures of the Navaho", in: Geographie heute, 1994, No. 117, pp. 16-19.

- The Spanish west. Time-Life Books, 1976.

- Alvin M. Josephy Jr.: 500 Nations. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-89405-356-9 .

- Alvin M. Josephy Jr.: The world of the Indians. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-89405-331-3 .

- John Gattuso (Ed.): Indian Reservations USA Travel and Transport Publishing, 1992.

- Tom Bathi: Southwestern Indian Tribes. KC Publications, Las Vegas 1995.

- Paul G. Zolbrod: On the way of the rainbow. The book of the origin of the Navajo. Weltbild, Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-142-8 .

- Bertha Pauline Dutton: American Indians of the Southwest , University of New Mexico Press, 1983, ISBN 0-8263-0704-3 .

- David Eugene Wilkins: The Navajo political experience , ISBN 0-7425-2398-5 , ISBN 0-7425-2399-3 .

Web links

- Official website of the Navajo Nation (English)

- Navajo Times website (English)

- Intranet of Navajo ( Memento of September 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- Indian web

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b US census from 2010 (PDF; 3.6 MB)

- ↑ Cindy Yurth (Tsé; yi 'Bureau): Census: Native count jumps by 27 percent, Navajo Times of January 26, 2012

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the prehistory is based on: Chip Colwell, TJ Ferguson: Tree-Ring Dates and Navajo Settlement Patterns in Arizona . In: American Antiquity, Volume 82, Issue 1 (January 2017), pp. 25–49

- ^ Chip Colwell, TJ Ferguson: Tree-Ring Dates and Navajo Settlement Patterns in Arizona . In: American Antiquity, Volume 82, Issue 1 (January 2017), pp. 25–49, 44–46

- ^ Marsha Weisiger: The Origins of Navajo Pastoralism . In: Journal of the Southwest , Vol. 46, No. 2 (summer 2004), pp. 253-282

- ↑ Navajo Clans

- ↑ a b Native Americans Fight to Save Language That Helped Win WWII ( Memento of 16 November 2015 Webcite ) (English), blogs.voanews.com, November 11, 2015 by Caty Weaver, Ashley Thompson and Adam Brock. Cf. Young Navajos Study to Save Their Language ( Memento from November 16, 2015 on WebCite ) (Video: 6:51 min; English), VOA Learning English, October 9, 2015, by Adam Brock, Caty Weaver and Ashley Thompson.

- ↑ Neue Zürcher Zeitung: The spider woman is back , April 20, 2015

- ↑ Grunfeld, Oker : Spiele der Welt II. Fischer, 1984.

- ↑ a b Christian F. Feest : Animated Worlds - The Religions of the Indians of North America. In: Small Library of Religions , Vol. 9, Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-451-23849-7 . Pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Steven Charleston et al. Elaine A. Robinson (Ed.): Coming Full Circle: Constructing Native Christian Theology. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, Minneapolis (USA) 2015, ISBN 978-1-4514-8798-5 . P. 31.

- ↑ Christian F. Feest: Animated Worlds - The religions of the Indians of North America. In: Small Library of Religions , Vol. 9, Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-451-23849-7 . P. 147.

- ↑ Wolfgang Lindig et al. Mark Münzel: The Indians. Cultures and history of the Indians of North, Central and South America. dtv, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-423-04317-X . P. 211.

- ↑ United States. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Navajo Agency (Ed.): The Navajo yearbook: Report. Washington DC 1958. pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Miriam Schultze: Traditional Religions in North America. In: Harenberg Lexicon of Religions. Harenberg, Dortmund 2002, ISBN 3-611-01060-X . P. 892.

- ↑ http://legacy.unreachedresources.org/countries.php (different content)

- ↑ Clanship System ( Memento from January 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Navajo Clans Legend - Twin Rocks Trading Post. Retrieved January 18, 2019 .