mother

Mother means the female parent of a person. The maternity is divided into three aspects - biological, legal and social parenthood:

- In a biological sense , mother is whoever contributed the egg from which the embryo was created. Since modern reproductive medicine makes it possible to transfer eggs and embryos, it can happen that several women are involved in the same pregnancy.

- Who is considered a mother in the legal sense depends on the laws of the respective society. In Germany , where surrogacy is politically undesirable, the new version of Section 1591 in the German Civil Code (BGB) in July 1998 stipulates : "The mother of a child is the woman who gave birth to it."

- In the social and psychological sense , mother is someone who shows motherly love to a child and thus creates the basis for the child to be able to establish his (mostly) first emotional bond with another person. This is usually associated with the care and upbringing of the child, and often also responsibility for education. Since social motherhood is not necessarily linked to biological motherhood, a child can also have several mothers, for example in a rainbow or blended family or as an adopted child , or if it is raised by its grandmother .

etymology

The word mother is derived from a reconstructed Indo-European root word * mātér- . The current form mother was preceded by the form muoter in Old High German and Middle High German ; the spelling with a simple u is first documented in the 15th century. As mother (with the Verwandtschaftssuffix -er is) the word cousin to the archaic Lallsilbe mā back.

Physiological perspective

- → See main articles: fertilization , nidation , pregnancy , childbirth

Most women come to motherhood naturally; H. by fertilizing a mature egg cell with a sperm from your male sexual partner through sexual intercourse and then implanting and carrying it to term in the uterus and finally giving birth to the child. Pregnancy, among many other factors, presupposes fertility in women, which usually begins with puberty and ends with menopause .

The Reproductive Medicine offers various possibilities, even to bring a pregnancy on the way, when the desire to have children through heterosexual intercourse can not be fulfilled or should.

Legal perspective

Who is mother

In a large number of countries - including the German-speaking countries - the legal definition of motherhood is based on the legal proverb Mater semper certa est .

Germany

In Germany, according to Section 1591 of the German Civil Code, the mother ("biological mother", in legal terminology also: "child mother") is who gave birth to the child. As a result, in the case of surrogate motherhood, it is not the commissioning woman who is the mother but the surrogate mother , even if she is not the genetic mother.

A woman can also become a mother by adopting a child.

A foster mother, on the other hand, is not a mother in the legal sense. She has no custody - this usually remains with the biological parents or with a guardian - but according to § 1688 BGB she has decision-making authority in matters of the child's daily life. A stepmother is when the biological parent of the child, a marriage or registered partnership comes in, with the child by marriage and, after § 1687B of the child to exercise BGB a "limited custody", that in matters of daily life in decisions. She only becomes a mother in the full legal sense if she adopts the child ( stepchild adoption ).

Austria

In Austria , Section 137b of the Austrian Civil Code, which was added in 1992, now Section 143 of the Austrian Civil Code : “Mother is the woman who gave birth to the child.” A mother-child relationship can also be legally established through adoption .

Switzerland

In Switzerland , Article 252, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code stipulates: "The child relationship between the child and the mother arises at birth." Paragraph 3 further states: "In addition, the child relationship arises through adoption" .

Other countries

The French and Italian law recognizes nor the - otherwise not usual in Europe - maternity recognition .

In different countries, two mothers or two fathers in a homosexual partnership or even more people can take on the right to bring up children .

Legal implications of motherhood in Germany

Due to the principle of equal rights from Article 3 GG , the legal implications of motherhood in Germany hardly differ from those of fatherhood or from those of parenthood in general. Exceptions include statutory maternity protection , maternity allowance and maternity insurance .

German criminal law has known the offense of child homicide since 1871 , which stipulated a milder penalty framework for mothers who killed their illegitimate child during or immediately after the birth (Section 217 of the Criminal Code); in the Prussian penal code, such a law as Section 180 had already existed before. Since being out of wedlock is hardly perceived as a blemish anymore, the fact became obsolete, so that the old § 217 was abolished in 1998; Since then, such acts have been treated as manslaughter . In the twelve years before the law was changed, the judiciary had dealt with an average of 26.7 infanticide per year.

Motherhood in Germany

The family in the old trade

The “old” handicraft , which was shaped by the guild order , existed from the High Middle Ages until around 1830. Handicraft businesses were characterized by a patriarchal constitution, strict guild supervision and pure subsistence farming. The living conditions were meager and the choice of partner was made under great objective and economic pressure. Masterwives had to meet high moral standards because they headed the “ whole house ” in a broader sense as the “mother”, and they also had to perform certain representative and other roles. In the company they only performed sales or handyman services, but were responsible for customer contacts, housekeeping, gardening and any sideline. Craftsman families only had 2-3 children on average because the marriage age and child mortality were high; Unlike in peasant families, children in artisan families were neither economically viable nor were they needed as heirs. The craft required a long apprenticeship; Children could only do auxiliary services. Her work was only really needed in the household and as a sideline. There were expenses for attending school and tuition fees, but these were not amortized. As heirs, children did not play a role in the trade because sons were not allowed to take over the father's business due to the obligation to migrate . Children grew up in a very confined space, often without their own beds, in a household in which the home and workplace were not divorced and in which mostly apprentices and a journeyman, and occasionally a maid, also lived. The mother was supported in looking after the children by older children, later the father and possibly the journeyman also brought up the children, the former typically with great rigor. The mother also demanded obedience, but was more loved than the generally brutal father. Education was geared towards obedience, hard work, modesty and religiosity. In addition to her own children, the foreman's wife also had to look after and raise the apprentices , who were hardly treated any differently from her own children. All behavior was strictly social controlled and often very formal; Spouses and children married their parents. The daughters, who learned housekeeping and reading, writing and arithmetic for household purposes from their mother, left the house after marriage, the sons either after their apprenticeship or - if they did not learn from their father - before their apprenticeship.

When handicrafts changed and became heterogeneous in the 19th century under the pressure of a changing economic world, the more affluent parts of this population gradually adopted the bourgeois family model, while the poorer craft classes became proletarianized.

The noble family

In the aristocracy , where descendants were mainly regarded as heirs, it was customary to take a child from the mother immediately after birth and give it to a wet nurse . The carefully selected wet nurse was usually brought into the house and was part of the usually very large household. The use of wet nurses meant, among other things, that women became pregnant again faster after giving birth and were able to give birth to more children overall.

Children were brought up strictly and intentionally from an early age, often not by their parents but by teachers.

The bourgeois family in the 18th and 19th centuries

Characteristic of the bourgeois family , which emerged as a type in the second half of the 18th century, were the emotionalization and intimacy of the marital relationship, the isolation of a private sphere and the central importance of children and their upbringing. Mothers no longer had anything to do with gainful employment, but the bourgeois image of women envisaged participation in certain areas of public life, especially literature and education , albeit primarily through reading . With the changed attitude towards marriage, the relationship between parents and their children also changed. The consanguinity was upgraded, and the now highly emotionalized mother-child relationship was valued as a “natural bond”. The fact that advances in knowledge in medicine that led to a reduction in child mortality were quickly accepted by the educated middle class also played a role . While the nobility traditionally had their offspring raised by wet nurses, nannies and other domestic staff, middle-class mothers nursed and raised their children themselves. Maids were omnipresent in middle-class households, but only took care of the day-to-day business of looking after the children. The bourgeois family was, according to their self-image, an educational institution. The mother's main task was to consciously raise the child as a “specialist”, i. H. to help him to freely develop his natural, rational tendencies, and to create the basis for the children to be included as educated conversation partners in the calm inner space of the family. The interaction between mother and children was tender and affectionate and characterized more by praise and blame than by corporal punishment. It was becoming increasingly common for children to use names on their parents. While the father worked outside the house, during the day, that is most of the time, only mother and children lived together. Unlike in the peasant family, however, the child was granted peculiarity; Adults and children slept in separate rooms. The actual lessons were not provided by the mothers, but by private teachers and schools.

The homeworker's family in the first half of the 19th century

The type of homeworker family emerged with the publishing system at the end of the 18th century, was most widespread between 1835 and 1850, and then - under the competitive pressure of industrial mass production - merged with the proletarian family type. The homeworkers had recruited themselves from the peasant classes, sat mainly in the country and suffered almost everywhere from extremely cramped living conditions, with the apartment also serving as a workplace. Homeworkers were more likely than farmers and artisans to be able to afford an individualized choice of partner, but they too showed a tendency towards professional endogamy based on economic considerations . H. Weber married Weber etc. Their households usually consisted only of the nuclear family , that is, of parents and children. Because starting a family was not tied to property, homeworkers married young and consequently had many offspring. Everyday family life - apart from limited space and a lack of privacy - was characterized by often crippling work in which all family members took part, by extremely long working hours, by inadequate food, by a patriarchal family structure and, despite the constant presence of all family members, by little family life. Child mortality was very high, especially since women could not afford to rest during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Mothers had little time for housework and child care, children - especially many children - were perceived as a burden. Older siblings had to help with the care of the younger ones; But the younger ones were also involved in the work as early as possible. A reflective upbringing did not take place, and since family relationships were often demoralized by the precarious living conditions and parents could not offer their children much besides food, they lost parental control early on - at the latest when the child left the house to work elsewhere.

The peasant family in the 19th century

From the liberation of the peasants to the end of the First World War , average farms in Germany were geared towards self-sufficiency and subsistence and only offered their residents poor living standards. The social relationships within the household were determined by a patriarchal hierarchy and economic constraints. Because a farm could not be run without a farmer's wife, marriage was on the one hand a necessity of life; the relationship between man and woman was to a large extent a working relationship, and partner choice instrumental. On the other hand, because marriage presupposed that the farmer had already acquired his own farm, the marriage age was high, which significantly lowered the birth rate. Women farmers - especially in the early years of a farm - did highly qualified and hard work, typically in the house, in the garden, in the dairy industry and with small cattle. Although children were used as cheap labor, as old-age security and as heirs, little consideration could be given to pregnancies and breastfeeding; Infants often had to be left unattended. As a result, child mortality was high, and the number of children that peasant couples raised in Germany in the 19th century, as the sum of all the factors mentioned here, was significantly lower than is often claimed without evidence. John E. Knodel, who examined rural demography using the example of a Bavarian village, came for example. B. on an average of 3 children. Mothers were in child care for older children and servants , more rarely of Einliegern , Inwohnern or Old dividers supported. Children were included in the work at an early age, but were also left to a great extent to themselves, received little parental attention and grew up without an intentional upbringing. The farmer, who exercised the authority of the household over the entire farm, prevailed with orders and corporal punishment; As a rule, mothers were less strict with children, but by no means affectionate. A sentimentalization of the mother-child relationship, as it emerged in the bourgeoisie in the 17th century, was opposed not only by the high child mortality rate in peasant families, but also by the widespread need to give children away to the servants at the age of 12. The close coexistence with the servants, who were often the same age as the farmer's children and treated the same way, did the rest to level the differences between one's own blood and those of others.

The working class family in the 19th century

The proletarian family type emerged in the second half of the 19th century with the expansion of urban factory work, which mainly attracted impoverished craftsmen and impoverished sections of the rural population. The living conditions in working-class households were characterized by lack of property, economic instability, long working hours, poor nutrition, poor and overpopulated housing, as well as a lack of privacy on the one hand and the constant separation of almost all family members during the day on the other. Because starting a family was not tied to property, marriages were concluded young, with relatively great freedom from economic considerations; however, the constant concern for their daily bread soon destroyed the relationship between the married couple. The low age at marriage and ignorance of birth control led to a particularly large number of children in working-class families; Even in the interwar period , German working-class families still had an average of 4.67 surviving children despite the high child mortality rate. Better-off sections of the workforce began to adapt bourgeois values, such as B. the idea that the woman belongs in the house. As soon as the money became scarce - for example because more children were born - women had to earn additional income, ideally with relatively well-paid factory work, otherwise in home work or through cleaning or washing work or by taking in subtenants , sleepers or foster children . If they were not left alone or placed under the supervision of older siblings in because the husband was the day mostly absent, had small children cribs , Bewahrschulen, Horten and kindergartens are housed or with relatives, neighbors or pulling mothers. Older children went to school or were left to their own devices or were socialized on the street. The situation became precarious when mothers were unable to earn more because they had too many children. Mothers generally suffered from the dominance and often violence of their husbands as well as being handcuffed to the house, were overloaded with work and could not expect consideration during their pregnancies and breastfeeding. Children - especially many children - meant material stress and a tendency to need. This could be alleviated through child labor , which was mostly done at home. For maintaining personal relationships, i. H. In working-class families, however, there was little time and energy left for family life. Instead of intentional, the upbringing was therefore natural and the parents' understanding of the value of a solid school education was poor. Children took up full employment at the age of 13-14 and usually left their parents' home as early as the opportunity arose.

From the second half of the 19th century, new laws improved the situation of working mothers. In 1878, for example, the Reichsgewerbeordnung (Section 138) created a first ban on women who had recently given birth in factories. Statutory health insurance was established in 1883 . The maternity leave was extended in several legislative amendments from the original 3 weeks to 8 weeks (1910); however, workers did not receive a loss of earnings.

The bourgeois family in the German Empire

A change in norms for the role of bourgeois women as mothers was anticipated in the second half of the 19th century through literary works such as Madame Bovary , Anna Karenina , Nora and Effi Briest . In all of these works there is a break in the hermetic logic of the bourgeois family structure, which had hitherto been apparently hermetic; the aporia of the role of women, who should be the individual as wife and mother but at the same time the servant of the family goal, turned into open conflict. At the political level, this change was reflected in the introduction of divorce (German Empire: 1875; Switzerland, nationwide: 1876). However, mothers continued to be severely disadvantaged in legal terms compared to their husbands. Under the Prussian General Land Law (1794–1900), children owed their mother awe and obedience , but were primarily under paternal authority . The latter was regulated down to the last detail and included a. determine how long a child should be breastfed and how they should be raised. After the entry into force of the Civil Code (1900), the primacy of paternal power remained undiminished.

During the German Empire, maternal upbringing was also determined by the gradually emerging scientific anthropology of children, which at the end of the 19th century led to the emergence of pediatrics and child psychology . The representatives of these young disciplines willingly gave educational recommendations in their writings, which were received attentively in the educated middle-class households. Together with the advice of experts, mothers received the impression for the first time in history that upbringing is an extremely delicate business, in which any deviation from the ideal line threatens the child with harm. One example is Alfred Adler , who warned parents in his book The Doctor as Educator (1905) on the one hand against lovelessness, but also against pampering children and accepting their caresses. Most educational authors of the time considered children to be instinctual and inconsistent “instinctual beings” who must be introduced to sensible and social behavior through conscientious upbringing.

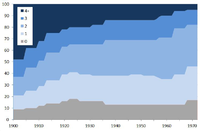

From the late 19th century onwards, the generally understandable scientific literature, which appeared in large editions, also included writings that gave information about the possibilities of contraception . The direct consequence was a massive drop in the fertility rate . Whereas women born in 1874 had an average of four children, those born in 1881 only had three children. The trend towards fewer children was first noticeable at the turn of the century and has continued almost steadily from then on; only the women born around 1930 had slightly more children again.

Weimar Republic

There had been a social discourse about improving the position of women and mothers in Germany since the first women's movement . Milestones in these developments were new statutory regulations on maternity protection and the introduction of women's suffrage in 1918 . In the Weimar Republic , maternity protection was further extended, women who had recently given birth also enjoyed protection against dismissal and were entitled to breastfeeding. In 1927 maternity leave was extended by law to twelve weeks (four weeks before, eight weeks after the birth); As in the German Empire, these regulations only applied to trade and z. B. not for domestic workers.

Due to celibacy clauses , married women and mothers were excluded from many professions (civil servants, teachers ). Households with two fully employed spouses were politically undesirable during the Weimar Republic, which had experienced mass unemployment, and in May 1932 the Reichstag created regulations that allowed married women to be dismissed from civil servants' positions.

The regulations on the legal representation of illegitimate children , which had previously been different under state law , were standardized in 1924 within the framework of the Reich Youth Welfare Act. Children born out of wedlock have since been given an official guardian by law ; de jure, the mothers could not exercise parental authority.

National Socialism

In his programmatic work Mein Kampf , Hitler wrote: “The goal of female upbringing has to be immovable to be the coming mother.” Since the National Socialist population policy was motivated by racial ideology - its goal was “racial unity” - it suited her, as Gisela Bock has shown , in addition to the official pronatalism but also an extreme antinatalism . “Valuable life” should be selected, “inferior life” should be eradicated. On the basis of the law for the prevention of hereditary offspring , which came into force at the beginning of 1934, around 200,000 women were forcibly sterilized by 1945 . Also forced abortions and infanticide were practiced on a large scale. The displacement of married women from working life that began in the Weimar Republic was continued under National Socialism; for example, if the woman gave up her job after marriage, couples could receive a non-interest-bearing marriage loan from 1933 on . Married doctors were revoked in 1934. Motherhood was massively propagated, Mother's Day became a public holiday in 1933, and women who had given birth to four or more children could, at the suggestion of the NSDAP local group leader or mayor, be awarded the mother's cross from the end of 1938 . From 1936 onwards, families with 5 or more children under the age of 16 were paid an ongoing child allowance, which was extended to families with 3 and 4 children in April 1938. The training courses for mothers organized by the Nazi women's group , which were based on Johanna Haarer's books The German Mother and Her First Child and Our Little Children , had a broad impact . National Socialism did not produce an independent anthropology of the child; Haarer's writings were interspersed with rhetoric of duty and sacrifice, but their pedagogy was little more than an exaggerated version of the pedagogy of the turn of the century. The mother and child relief organization, founded in 1934, provided care for pregnant women and women who had recently given birth with the help of voluntary workers, supported single mothers, operated day-care centers and organized mother and child recovery programs. The facilities of the Lebensborn organization, which was originally founded in 1935 to enable illegitimate mothers of “ Aryan ” children to give birth anonymously and adoptions, were actually only used by a few thousand German women.

After - u. a. Due to the armament policy - full employment was reached in 1936 and a serious labor shortage emerged as early as 1937, the restrictions on women’s work were relaxed again. Starting in 1938, many households with children were assigned compulsory year girls.

In the course of the Second World War , the labor shortage increased so strongly that female employment - including the employment of mothers - was expressly desired from around 1942. On July 1, 1942, the Maternity Protection Act was significantly improved; it now also applied to domestic workers, agricultural workers and homeworkers, including employment restrictions for expectant and nursing mothers, protection against dismissal for pregnant women and an increase in maternity allowance to the level of full wages. From 1944 onwards, a breastfeeding allowance that had previously only been granted to working women could be used by all mothers for 26 weeks. Since 1942, the Reich Ministry of Labor has been able to oblige companies to either set up company kindergartens or to support municipal institutions financially. From October 1943 onwards, all employed women were entitled to an unpaid monthly housework day .

An increase in the birth rate was not achieved during the National Socialist era, despite all propaganda and family policy measures; the trend towards two-child families, which was already observable at the turn of the century, continued unabated from 1933 to 1945 (see graphics above ). The average age at first marriage for women during the Nazi era was even higher than ever before in the 20th century, namely 26.2 years (1938).

The most important medical innovation of the time was the introduction of obstetric epidural anesthesia in Germany by Karl Julius Anselmino (1944), which for the first time in history enabled women to have a largely painless vaginal birth.

Federal Republic of Germany (1945–1965)

The 1950s and 1960s, which in the Federal Republic of Germany were sociologically characterized by an almost complete integration of the population into families, are sometimes referred to as the golden age of marriage . Since 1949, at the request of the parents , the Federal President has been symbolically sponsoring the seventh child in a family. To promote maternal health , the maternal recovery organization was founded in 1950 . The law for the protection of working mothers (Mutterschutzgesetz) passed in 1952 largely corresponded in content to the corresponding law of 1942. As a result of Article 117 of the Basic Law , from 1953 onwards all older legal regulations that violated the principle of equal rights in Article 3 were no longer applicable. Among other things, this concerned the father's priority over parental authority, which was still anchored in the BGB. As the core of the equalization of family burdens in 1954 under the CDU Family Minister Franz-Josef Wuermeling the child benefit introduced, but the first only workers with at least three children state. The gainful employment of wives and mothers was also made easier, for example with the abolition of the last celibacy clauses (1956/1957).

The birth rate, which had continued to decline until the Nazi era , increased slightly in the cohort of women born around 1930, the majority of whom married in the 1950s. These women had an average of 2.2 children. Authors such as Johanna Haarer continued to set the tone in the advisory literature, and she published her works - now cleared of National Socialist rhetoric - until 1987. As early as 1952, Benjamin Spock's standard work Infant and Child Care appeared for the first time in German translation, which was based on Freud's psychoanalysis and a modern infant anthropology, which understood the child not as an instinct to be domesticated but as a young person to be treated with dignity and love. In 1950, industrially produced infant formula similar to breast milk was available for the first time in Germany ( Humana ), and this helped bottle-feeding to gradually increase.

Motherhood in the GDR

Demographics

The birth rate in the GDR - especially in the cohort of women born up to 1965 - was slightly higher than in the Federal Republic. Women in the GDR also married about two years younger than in the FRG; they had their first child one or two years earlier.

Family policy

The distinction between legitimate and illegitimate children was in the German Democratic Republic with the Law on the mother and child protection and women's rights have been abolished already 1950th Couples who married up to the age of 26 could, however, claim an interest-free loan of 5,000 marks , a quarter of which was waived at the birth of each child (“childbearing”). Mothers who had regularly attended pregnancy counseling received 1000 marks in birth assistance per birth. Full wages were paid during pregnancy (6 weeks before delivery) and maternity leave (20 weeks after delivery). In the case of the first and second child, it was also possible to take time off work up to the end of the child's first year of life, with continued payment of 65–90% of the salary. Parents received child benefit .

Maternal employment

The women's and family policy of the GDR relied much more strongly than that of the Federal Republic on emancipation and equality for women . To make it easier to combine motherhood and work, the day nursery and kindergarten network has been rigorously expanded. Most of the under 3-year-olds were looked after in day nurseries, which, however, were poorly equipped, especially in terms of staff. 94% of preschool children were cared for in kindergartens, mostly all day. 81% of the 6-10 year old school children in the afternoon visited a Hort . Working mothers were also entitled to one day off each month for household work .

State child abduction

Since the early 1950s at the latest, permanent homes for babies and toddlers existed in the GDR , in which healthy children under the age of 3 were permanently housed, including orphans and social orphans , but also children of single women and couples who worked in shift systems. Parts of the SED leadership promoted the expansion of these homes until the early 1960s because they saw an opportunity for early socialist education here, while critical voices were hardly heard; the facilities existed until reunification . As was first made public in 1975 through a Spiegel article, there were also occasional forced adoptions in the GDR , which mainly affected families with parents who had fled the GDR .

Federal Republic of Germany (1965–1980)

After the end of the Adenauer era , maternity protection was further extended in two amendments to the law (1965, 1968). The protection periods from 1968 included 6 weeks before and 8 weeks after delivery. From 1979 onwards, women were able to take federally funded 4-month maternity leave beyond these protection periods .

In 1968, the health insurance companies in Germany took over the costs of hospital births , with the result that the number of home births fell drastically.

The “second wave” of feminism , which developed in Germany parallel to the 1968 movement , changed demographics and measurable social structures only slightly. For example, the female employment rate , which at 30.3% from 1968 to 1970 was lower than ever before in post-war German history, rose to only 33.8% by 1980, a level that it had already had in 1957/1958 would have. Women married young, had children at an early age and led the majority of their lives as housewives . The (limited) legalization of abortions (April 26, 1974 to February 25, 1975; again since May 6, 1976), which was fought for by the women's movement , had no noticeable impact on the birth rate, as contraceptives had already been readily available.

However, the accelerated boom in public interest in early childhood education had a major practical impact on the everyday life of mothers . The magazine Eltern was published for the first time in 1966, the first children's shop was opened in Frankfurt in 1967, the specialist magazine Kindergarten heute appeared in 1971 , and in 1972 the Bavarian State Institute for Early Childhood Education was established . The supply rate for kindergarten care rose from 33% (1965) through 36% (1969) to 66% (1975), but then stagnated. In 1980, 1,393,708 kindergarten places and 105,673 after-school care places were counted in the FRG. The supply of crèche places also rose at a very low level (1960–1970: 0.6%; 1975: 1.3%; 1980: 1.5%).

The era of the social-liberal coalition brought mothers further improvements in their legal and economic situation. For example, the mandatory official guardianship for children born out of wedlock was abolished under the law of illegality of 1970 . Women were thus fundamentally entitled to exercise parental authority over illegitimate children; however, the guardian was replaced by an official guardian , whose responsibilities continued to restrict the parental authority of the illegitimate mother in some points. The pension reform of 1972 opened the statutory pension insurance for the first time to housewives, who from now on were able to pay pension contributions voluntarily. From 1975 onwards, child benefit was also paid out to first-born children for the first time. In 1977, with the law reforming marriage and family law, the model of “ housewife marriage ” was replaced by the partnership principle; the economically weaker spouse could demand maintenance from the economically stronger one after a divorce.

Bottle feeding became most widespread in the mid-1970s; around half of all infants received exclusively industrial baby food during this period .

Federal Republic of Germany (1980–2000)

Up until the 1980s there were private “ maternity homes ” in West Germany in which unmarried women could give birth discreetly and give their child up for adoption; this release was often withheld from women. In 1984 a federal foundation for mother and child was established in Bonn , which has since supported pregnant women in financial distress with grants averaging 600 euros. In 1996 child benefit was increased significantly; Families with 2 children e.g. B. received 400 DM instead of 200 DM. At the same time, all children between the ages of 3 and starting school were given a legal right to a place in a kindergarten. An Employment Promotion Act, which came into force in 1985, was intended to facilitate access to retraining and further training measures for women who have temporarily withdrawn from working life to raise children. In 1986 the so-called “baby year” was introduced with the survivors' pensions and parental leave law, which means that parental leave periods can be offset against the statutory pension insurance ; the law was later expanded several times. The Federal Education Allowance Act also came into force in 1986 , on the basis of which mainly mothers could receive compensation for lost employment; this law was also extended afterwards.

The indication regulation of § 218, with which abortion is criminally regulated, was in fact replaced by a time limit in 1993 after a decision of the Federal Constitutional Court , so that from now on women could also abort with impunity for whom a social indication would not have come into question.

The silence had recovered proliferation since the mid-1970s. A 1997/1998 study found that 91% of all mothers had tried breastfeeding in hospital at least once; 58% of the children examined had been breastfed for at least 4 months, 48% had been breastfed for at least 6 months.

Younger past and present

Demographics

78% of women who were 40 to 44 years old in 2013 are mothers. In eastern Germany (85%) it is significantly more than in western Germany (77%). The proportion of female graduates is particularly low (female academics between 45 and 49 years: 70%; as of 2012).

The total birth rate in Germany has been largely stable at a very low level since around 1975. In 2014 it was 1.47 children per woman.

In 2015, the Federal President took on 550 honorary sponsorships for the seventh child from parents who submitted a corresponding application (2014: 600, 2013: 600, 2012: 460, 2011: 670, 2010: 603).

In 2014, the average age of women giving birth to their first child was 29.5 years, although it is usually higher in the western federal states than in the eastern states. In 2013, first-time mothers in Germany were on average 29 years old. In 2007 the average age was 26 years.

In 2014 there were around 2,307,000 single mothers in Germany (2000: 1,960,000, 2005: 2,236,000, 2010: 2,291,000).

Employment of mothers and childcare

In 2002, after the absolute number of children had fallen sharply, kindergarten places were available for 90% of all children of preschool age. The legal right to early childhood support has been in place since August 1, 2013 when the child is 1. The employment rate is significantly lower for mothers than for fathers; in 2013 it was e.g. For example, around 40% of the 27-year-olds (fathers: around 80%). 31.4% of the mothers of young children went to work (West: 30.2%, East: 36.4%). In 2013, around 60% of mothers who had a youngest child at kindergarten age (3–5 years) were employed in the west and 67.5% in the east.

In 2018 were 42.1% of working mothers who had at least one child under 3 years in parents' time , so unpaid from work exempted (Fathers: 2.7%); of the mothers with at least one child under 6 years of age, the figure was 24.5% (fathers: 1.6%). Overall, the proportion of parents on parental leave whose youngest child was under 6 has risen from 9.1% to 12.6% in the last ten years.

Parenting trends and family debates

Well-educated mothers who live in a metropolitan environment and are interested in social and ecological issues have helped attachment parenting, which originated in the USA, to an upswing in Germany since the 2000s .

Another new cultural phenomenon are statements such as those by Sarah Fischer ( Die Mutterglück-Lüge , 2016) and Esther Göbel ( The wrong choice , 2016), the follow-up to Orna Donath's much-acclaimed Israeli study Regretting motherhood, also in the German-speaking area of the disappointment of women Trying to create a public hearing and understanding who have regretted their decision to have children and are thus in stark contradiction to authors such as Alina Bronsky and Denise Wilk ( The Abolition of Mother , 2016), who ardently defend motherhood.

Superlatives

Barbara Stratzmann is considered to be the woman with the most births in the history of Germany, with allegedly 53 children (in the 15th / 16th century), none of whom were older than 8 years. The Guinness Book of Records names the woman of the Russian farmer Feodor Vassilyew, who is not known by name as the mother of the largest number of children in the world , who in the 18th century had 69 children (16 twins, 7 triplets and 4 quadruplets) in 27 births Should have given life.

The Peruvian Lina Medina became the youngest mother in the world at the age of five . One of the youngest mothers in Germany is a girl from Hamburg who was born in 2006 at the age of 12. In 1999, a twelve-year-old from Naumburg gave birth to a child. The youngest mother in Austria is said to have been 11 years old when she gave birth (2008); the youngest in Switzerland was 13 years old (2008).

María del Carmen Bousada achieved fame in 2006 when she gave birth to twins at the age of 66 following fertility treatment . The woman who gave birth in old age is currently Daljinder Kaur, a woman from India who gave birth to her first child in 2016 at the age of at least 70 following fertility treatment. In Berlin in May 2015, 65-year-old mother of quadruplets was born.

iconography

In the visual arts , the representation of mothers plays an important role in all human cultures. The pictorial representation of mothers begins in prehistory with Paleolithic Venus figurines and cave paintings of pregnant and breastfeeding women, goes through medieval portraits of Mary and Pietàs and extends to modern art , such as Niki de Saint Phalles “ Nana ” sculptures.

Psychoanalytic perspective

As a mother archetype , also called great mother or primordial mother , the meaning of the mother plays a central role in the analytical psychology according to Carl Gustav Jung .

See also

- Maternity Insurance (Switzerland)

- Housewife and mother - housework and family work - women's work

- Global care chain (cross-state redistribution of care tasks)

- Kinship relationship

- mom and dad

literature

- Elisabeth Badinter : Mother's love. History of a feeling from the 17th century to today. dtv, Munich 1984.

- Christine Brinck : Mother's Wars. Are our children being nationalized? Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2007, ISBN 978-3-451-03005-5 .

- Phyllis Chesler : Becoming a mother. The story of a transformation. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1985.

- Mary Jacobus: First Things. The maternal imaginary in literature, art, and psychoanalysis. Routledge, New York et al. a. 1995 (English).

- Doris Klepp: The life situation and subjective quality of life of women with children aged 0 to 6 years. An Empirical Psychological Study on Motherhood. In: Brigitte Cizek (ed.): ÖIF writings. Issue 12, Austrian Institute for Family Research, Vienna 2004, pp. 81–108 ( PDF file; 130 kB; 28 pages PDF on Familienhandbuch.de).

- Elsbeth Kneuper: Becoming a mother in Germany. An ethnological study. In: Forum European Ethnology. Volume 6, Lit, Hamburg 2004.

- Renate Möhrmann (Ed.): Transfigured, kitschy, forgotten. The mother as an aesthetic figure. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1996.

- Julia C. Nentwich: How mothers and fathers are made - constructions of gender in the distribution of roles in families. In: Journal for Women's Research & Gender Studies 18 (2000), No. 3, pp. 96–121.

- Ulrike Prokop : Motherhood and the Maternity Myth in the 18th Century. In: slave or citizen? French Revolution and New Femininity 1760–1830. Jonas, Frankfurt 1989.

- Adrienne Rich : Of Woman Born. Motherhood as Experience and Institution. Virago Press, 1995 (English).

- Barbara Vinken : The German mother. The long shadow of a myth. Piper, Munich 2002.

- Elma van Vliet: Mom, tell me! The memory album of your life. Knaur, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-426-66264-9 .

Movies

- Dominique Cabréra: Le lait de la tendresse humaine. (German: Milk of tenderness. ) France / Belgium 2001 (feature film).

- Helke Sander : mother animal - mother man. Germany 1998 ( essay film ).

- Maria Speth : Madonnas. Germany / Switzerland / Belgium 2007 (feature film).

Web links

- Helmut Rüßmann : The question of fact: Who is the biological mother? In: Biological Parenthood. Own website, 1996, accessed on September 21, 2018 (former chair for civil law and legal philosophy).

- Martin R. Textor: Becoming a mother - motherhood. (No longer available online.) In: Family handbook of the State Institute for Early Childhood Education. Bavarian State Ministry for Labor and Social Affairs, Family and Women , December 30, 2006, archived from the original on December 31, 2010 ; Retrieved on September 21, 2018 (ibid .: Mother Pictures ( Memento from December 31, 2010 in the Internet Archive )).

- Gaby Sutter: motherhood. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . Article dated September 2, 2010, accessed September 21, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ German Civil Code (BGB): § 1591 Mutterschaft , Version from July 1, 1998, see version comparison on lexetius.com.

- ^ German dictionary by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm: Mother. Retrieved December 4, 2015 .

- ^ German dictionary by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm: Muhme. Retrieved December 4, 2015 .

- ↑ Men , because they neither produce eggs nor have a uterus, can only become mothers under extremely rare and special circumstances. You can only have children if they were born with a uterus and have achieved their male gender identity as transsexuals , e.g. B. Thomas Beatie , who gave birth to a daughter in 2008 (see also: en: Transgender pregnancy ). Uterine transplants have never been successfully performed in transsexual women. ( Uterus transplant surgery Could Help Transwomen to become pregnant. Retrieved on 3 January 2016 . ) The implantation of an in vitro conceived embryos in the male abdominal cavity with growth of the placenta is applied to an internal organ such as the intestine by individual physicians, approximately Robert Winston , considered theoretically possible, but generally - if at all possible - assessed as extremely dangerous, just as female ectopic pregnancies rarely lead to live births. ( Meryl Rothstein: Male pregnancy: A dangerous proposition. Retrieved on January 3, 2016 . ; See also: en: Male pregnancy )

- ↑ Swiss Civil Code. Retrieved January 4, 2016 .

- ^ Frankfurter Rundschau : Two mothers and a baby. January 6, 2007, p. 14.

- ↑ Number of child killings according to § 217 StGB in Germany from 1987 to 1998. Retrieved on April 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Beatrix Bastl: Virtue, Love, Honor: the noble woman in the early modern age . Böhlau, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-205-99233-4 , p. 505 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Karl Haag: When Mothers Love Too Much: Entanglement and Abuse in the Mother-Son Relationship . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-019029-6 , pp. 182 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Sandra Schmid: Childhood in the Middle Ages. Retrieved April 17, 2016 .

- ↑ Herbert Schweizer: Sociology of Childhood: Vulnerable Eigen-Sinn . Springer, 2007, p. 362 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Winfried Speitkamp: Youth in the Modern Era: Germany from the 16th to the 20th Century . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-01374-4 , pp. 124 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Three-generation families were the exception rather than the rule. Heidi Rosenbaum: Forms of the Family . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-518-07974-3 , pp. 62 f., 92 .

- ↑ Robert von Landmann (ed.): The trade regulations for the German Empire, taking into account the legislative materials, practice and literature. 2 volume . CH Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Munich 1895, p. 973 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Birgit Fix: Religion and Family Policy: Germany, Belgium, Austria and the Netherlands in Comparison . Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-531-13693-3 , pp. 50 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Prussian General Land Law: 2. Title: From the mutual rights and duties of parents and children. (PDF) Retrieved December 7, 2015 . ; Arne Duncker: Equality and Inequality in Marriage: Personal Position of Women and Men in the Law of Marital Partnership 1700–1914 . Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-412-17302-9 , pp. 1041 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Civil Code, version from 1896/1900. Retrieved on December 7, 2015 (§ 1626ff, 1684ff).

- ↑ Data source: Bernd Camphausen: Effects of demographic processes on professions and costs in the health care system . Springer, Berlin a. a. 1983, ISBN 3-540-12694-5 , pp. 30 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Martinus Jan Langeveld: Studies on the anthropology of the child . 3. Edition. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1968 ( limited preview in the Google book search - first edition: 1956).

- ↑ Robert Eugen Gaupp : Psychology of the child . 5th edition. Springer, Wiesbaden 1925, p. 64 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book Search - first edition: 1908).

- ^ Robert Jütte: Lust Without Load: History of Contraception from Antiquity to the Present . C. H. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49430-7 , p. 13 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Herweg Birg: The demographic turning point: The population decline in Germany and Europe . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-47552-3 , p. 51 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Günther Schulz: Social security for women and families . In: Hans Günter Hockerts (ed.): Three ways of German welfare state: Nazi dictatorship, Federal Republic and GDR in comparison . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-64576-5 , p. 125 ( limited preview in Google Book Search). ; Christiane Dienel: Population Policy in Germany. Retrieved January 2, 2016 .

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1914–1949. Volume 4 . 2nd Edition. CH Beck, 2003, ISBN 3-406-32264-6 , pp. 365 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Kathrin Kompisch: Perpetrators. Women under National Socialism . 2nd Edition. Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20188-3 , pp. 40 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Mein Kampf, pp. 459f

- ↑ Astrid Messerschmidt: Controversial Remembrance - Appropriation of the Holocaust Memory in Women and Gender Studies . In: Elisabeth Tuider (Ed.): QuerVerbindungen: Interdisciplinary approaches to gender, sexuality, ethnicity . Lit, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-8258-8879-4 , pp. 234 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Rüdiger vom Bruch: The Berlin University in the Nazi era. Volume 2 . Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-515-08658-7 , pp. 234 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Norbert Moissl: aspects of midwifery in the era of National Socialism from 1933 to 1945 using the example of the First Women's Hospital, University of Munich. (PDF) Retrieved December 28, 2015 .

- ^ Sabine Schleiermacher: Race hygiene mission and occupational discrimination. Agreement between women doctors and National Socialism . In: Ulrike Lindner, Merith Niehuss (Ed.): Doctors - patients. Women in German and British Healthcare in the 20th Century . Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-412-15701-5 , pp. 101 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Asmus Nitschke: The "Erbpolizei" in National Socialism. On the everyday history of the health authorities in the Third Reich. The example of Bremen . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-531-13272-5 , pp. 131 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Gudrun Brockhaus: Mother power and fear of life. On the political psychology of the Nazi educational adviser Johanna Haarers . In: José Brunner (ed.): Maternal power and paternal authority. Parent images in the German discourse . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0244-0 , p. 63, 72 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Christine Aman: The new contact law. Critical inventory from the perspective of women . Diplomica Verlag, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8366-9440-7 , p. 187 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Günther Schulz: Social security for women and families . In: Hans Günter Hockerts (ed.): Three ways of German welfare state: Nazi dictatorship, Federal Republic and GDR in comparison . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-64576-5 , p. 124 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Maternity Protection Act 1942. Retrieved December 29, 2015 . ; Calendar sheet. Retrieved December 29, 2015 . ; Protection periods according to the Maternity Protection Act. Retrieved December 29, 2015 .

- ^ A b Maria Mesmer: Births / Control: Reproductive Policy in the 20th Century . Böhlau, Vienna, Cologne, Weimar 2010, ISBN 978-3-205-78320-6 , pp. 168 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Günther Schulz: Social security for women and families . In: Hans Günter Hockerts (ed.): Three ways of German welfare state: Nazi dictatorship, Federal Republic and GDR in comparison . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-64576-5 , p. 126 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Jürgen Cromm: Family education in Germany. Sociodemographic processes, theory, law and politics with special consideration of the GDR . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1998, ISBN 3-531-13178-8 , pp. 140 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Anniversaries and honorary sponsorships. Retrieved April 10, 2016 .

- ↑ Hannes Ludyga: Maternity leave in the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 2000 . In: Thomas Vormbaum (Hrsg.): Yearbook of the Institute for Justistic Contemporary History Hagen. Volume 8 (2006/2007) . Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8305-1471-8 , pp. 203 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ The Civil Code with special consideration of the case law of the Reich Court and the Federal Court of Justice. Comment. Volume IV, part 3 . 12th edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1999 ( limited preview in the Google book search - before § 1626, section 4f).

- ↑ Herweg Birg: The demographic turning point: The population decline in Germany and Europe . CH Beck: Munich, 4th edition 2005, ISBN 3-406-47552-3 , p. 51.

- ↑ See graphic above

- ↑ See graphics below

- ↑ Family Code of the German Democratic Republic. Retrieved April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Eva Kolinsky: Women in 20th-century Germany. A reader . Manchester University Press, Manchester, New York 1995, ISBN 0-7190-4654-8 , pp. 256 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Act to amend the Maternity Protection Act and the Reich Insurance Code. August 24, 1965 (PDF). Retrieved April 7, 2016 . Announcement and revision of the Maternity Protection Act. Dated April 18, 1968 (PDF). Retrieved April 7, 2016 .

- ↑ Law on the introduction of maternity leave. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 10, 2016 ; Retrieved April 7, 2016 .

- ^ Brigitte Borrmann: Between tutelage and professional autonomy: the history of the Association of German Midwives . Association of German Midwives, 2006, p. 146 .

- ↑ Employed persons, employment rates, employed nationals by gender. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 10, 2016 ; Retrieved April 8, 2016 .

- ^ A b c Thomas Bahle: Ways to the service state. Germany, France and Great Britain in comparison . Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-15089-5 , p. 263 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search). Monika Langkau-Herrmann, Jochem Langkau: The professional advancement of women: labor market strategies for greater integration into the world of work and professional life . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1972, ISBN 3-531-02232-6 , pp. 133 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Karl Wilhelm Jans: youth welfare . In: G. Püttner (Hrsg.): Handbook of communal science and practice. Volume 4: The specialist tasks . 2nd Edition. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo 1983, ISBN 3-642-68260-X , pp. 382 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ German social insurance: history. Retrieved April 7, 2016 . Wolfgang Wehowsky, Harald Rihm: Practice of the statutory pension . 2nd Edition. expert verlag, Renningen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8169-2986-4 , p. 5 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Child benefit since 1963. Accessed April 9, 2016 . Development of the amount of child benefit since 1975. Accessed April 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Timo Heimerdinger: Breast or Bottle. (PDF) Retrieved April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ Nadine Ahr , Christiane Hawranek : The fallen girls. In: Zeit Magazin. June 13, 2018, accessed July 9, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Legal entitlement to child day care. Retrieved April 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Measures and laws for equality since 1949. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 9, 2016 ; Retrieved April 9, 2016 . Employment Promotion Act. (PDF) Retrieved April 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Breastfeeding in Germany - an inventory. Retrieved April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ M. Kersting, M. Dulon: Assessment of breast-feeding promotion in hospitals and follow-up survey of mother-infant pairs in Germany: the SuSe Study. In: Public health nutrition. Volume 5, Number 4, August 2002, pp. 547-552, doi: 10.1079 / PHN2001321 , PMID 12186663 .

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office: More and more women remain childless. Retrieved April 12, 2016 (Der Spiegel, November 7, 2013).

- ↑ Highest birth rate since reunification. Retrieved on April 11, 2016 (FAZ, April 11, 2016). European comparison: European Union: fertility rates in the member states in 2013. Accessed on April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ Age of mother. Retrieved April 10, 2016 .

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): 682,000 children were born in 2013 . Press release No. 434/14 dated December 8, 2014.

- ↑ Number of single parents in Germany by gender from 2000 to 2014. Accessed on April 12, 2016 .

- ^ A b Angelika Koch: Compatibility of employment and parenthood . In: Claudia Maier-Höfer (Ed.): Applied Childhood Sciences. An introduction to the paradigm . Springer, 2016, ISBN 978-3-658-08119-5 , pp. 161 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office : Quality of work for people on parental leave. In: destatis.de. September 11, 2019, accessed August 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Sarah Fischer: The mother luck lie . Ludwig, 2016, ISBN 978-3-453-28079-3 . Esther Göbel: The wrong choice. When women regret choosing to have children . Droemer, 2016, ISBN 978-3-426-27680-8 .

- ↑ Alina Bronsky, Denise Wilk: The Abolition of the Mother: Controlled, manipulated and cashed in - why it cannot go on like this . DVA, 2016, ISBN 978-3-421-04726-7 . Susanne Mayer : Is it still possible? Retrieved April 12, 2016 (Die Zeit, March 14, 2016). Harald Martenstein : About the children of repentant mothers. Retrieved April 12, 2016 (Die Zeit, April 12, 2016).

- ↑ Most prolific mother ever. In: Guinness World Records. Retrieved April 9, 2018 .

- ^ Bettina Mittelacher: Luiza (12) - Germany's youngest mother. In: Hamburger Abendblatt. March 2, 2006, accessed April 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Norbert Kluge: Early and Late Birth in Germany ─ Spectacular press reports and statistical findings. (PDF) In: Contributions to Sexology and Sex Education, August 2011. Accessed April 9, 2018 .

- ^ A woman from India, 70, will be a mother for the first time. In: 2016-05-11. Retrieved April 9, 2018 .

- ↑ The everyday life of the oldest quadruplet mother in the world. Retrieved January 4, 2016 . Die Welt, December 29, 2015.

- ↑ Arisika Razak: "I Found God in Myself": Sacred Images of African and African-American women . In: Annette Lyn Williams, Karen Nelson Villanueva, Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum (eds.): She is Everywhere! An Anthology of Writing in Womanist / Feminist Spirituality, Volume 2 . iUniverse, New York, Bloomington 2008, ISBN 978-0-595-46668-9 , pp. 21–40 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ( R ): Heidi Rosenbaum: Forms of the Family: Investigations into the connection between family relationships, social structure and social change in German society in the 19th century. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 3-518-07974-3 .

- ↑ pp. 124, 134

- ↑ P. 126/127, 134, 153, 156 ff.

- ↑ p. 145, 152/153.

- ↑ p. 147.

- ↑ pp. 127, 147, 154-156.

- ^ Pp. 142, 148/149, 162.

- ↑ pp. 138, 142, 163 ff.

- ↑ pp. 127f, 135, 137, 167/168, 175.

- ^ Pp. 158, 166-169.

- ↑ pp. 168/169.

- ↑ P. 171 ff., 175.

- ↑ pp. 131, 137, 147, 177/178.

- ↑ pp. 131, 183.

- ↑ pp. 138, 142/143, 154.

- ↑ pp. 183-188.

- ↑ pp. 251, 264 ff., 276, 285 ff.

- ↑ pp. 252, 266.

- ↑ p. 263.

- ↑ pp. 268, 270, 280.

- ↑ p. 282.

- ↑ p. 267/268.

- ↑ p. 278.

- ↑ pp. 269/270, 279, 283.

- ↑ p. 300.

- ↑ p. 296.

- ↑ p. 304.

- ↑ pp. 269/270, 280.

- ↑ pp. 269/270, 296 ff.

- ↑ p. 194, 196.

- ↑ pp. 189, 192/193, 199, 201/202.

- ↑ pp. 221/222, 228.

- ↑ p. 209.

- ↑ pp. 201, 211, 216 ff., 237.

- ↑ pp. 200, 202/203, 231, 234, 241, 243, 248.

- ↑ p. 212/213.

- ↑ pp. 238, 230/231, 235, 240/241, 243/244.

- ↑ pp. 241, 248.

- ↑ pp. 209, 236, 241, 245, 248.

- ↑ pp. 48/49, 58.

- ↑ pp. 81, 85.

- ↑ P. 52/53, 69/70, 72 ff., 87.

- ↑ This is even more true for an inheritance areas than for areas with real division ; see pp. 62, 64, 70 ff.

- ↑ P. 52/53, 69/70, 72 ff., 80/81.

- ↑ pp. 65, 86, 89, 91, 165.

- ↑ p. 65; see also John E. Knodel: Two and a Half Centuries of Demographic History in a Bavarian Village (Anhausen). In: Population Studies. Volume 24, 1980, p. 353 ff.

- ↑ pp. 90, 92-94.

- ↑ pp. 81, 85, 98.

- ↑ p. 94, 102.

- ↑ pp. 68, 103.

- ↑ pp. 383, 385.

- ↑ pp. 381, 383, 390/391, 412 ff., 417 ff., 421, 434.

- ↑ pp. 406, 428, 438, 464.

- ↑ pp. 385, 423, 429, 433/434.

- ↑ p. 439, 442/443, 456.

- ↑ pp. 397, 402 ff., 410, 435, 441.

- ↑ P. 456/457, 407 ff., 457.

- ↑ pp. 408, 412, 458.

- ↑ p. 437.

- ↑ pp. 408, 424/425, 438/439, 444 ff., 456, 458 ff., 467.

- ↑ pp. 449, 454.

- ↑ pp. 385, 389, 410 ff.

- ↑ pp. 396, 409, 412, 469.

- ↑ p. 456.

- ↑ P. 460/461 and 464/465.