Article 3 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

The Article 3 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany is part of the first section ( fundamental rights ) and guarantees the equality before the law , the equality of the sexes and prohibits discrimination and favoritism because of certain properties. This is an equality law .

Normalization

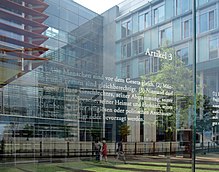

Article 3 of the Basic Law has read as follows since its last amendment on November 15, 1994:

(1) All people are equal before the law.

(2) Men and women have equal rights. The state promotes the actual implementation of equality between women and men and works towards eliminating existing disadvantages.

(3) Nobody may be disadvantaged or preferred because of their sex, their origin, their race, their language, their homeland and origin, their beliefs, their religious or political views. Nobody may be disadvantaged because of his disability.

Art. 3 paragraph 1 GG contains the general principle of equality which obliges the state to treat all people equally. The following paragraphs contain special guarantees of equality that prohibit unequal treatment on the basis of certain characteristics.

According to Art. 1 Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law, the equality clauses bind the three powers of the state, the executive , legislative and judiciary . The formulation of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG; according to which equal treatment only takes place before the law is therefore formulated too narrowly according to the general opinion. According to the prevailing view, the rights of equality also apply within limits between private individuals. Although these are not directly bound by fundamental rights, Art. 3 GG as a constitutional norm influences the handling of subordinate legal clauses, such as civil laws , through the case law in the context of court proceedings. This indirect third-party effect means that the essential statements of Art. 3 GG find their way into private law, in particular when interpreting indefinite legal terms . The third-party effect influences, for example, the legal treatment of market monopolies or collective agreements . On the other hand, Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law does not contain a right of citizens against the state for protection against unequal treatment. This would amount to an obligation of the state to intervene in the rights of private individuals. This represented a contradiction to the fact that Art. 3 GG does not bind private persons directly.

History of origin

The earliest predecessor of Article 3 of the Basic Law in German constitutional history is Article 137 of the Paulskirche constitution of 1849. According to this, there was no difference between the statuses before the law. Furthermore, status privileges and the nobility were canceled. Art. 137 WRV was developed on the basis of the guarantee of equality in the French constitution of 1791. Due to the resistance of numerous German states, however, the Paulskirche constitution did not prevail, so that this guarantee had no legal effect.

The Weimar Constitution (WRV) obligated the state to treat all Germans equally before the law through Art. 109 Paragraph 1 WRV. According to this, men and women basically had the same civil rights and duties.

In the course of the development of the Basic Law between 1948 and 1949, the Parliamentary Council took over the guarantee of Art. 109 Paragraph 1 WRV, but abandoned the restriction of its scope to Germans. Otherwise, the formulation of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law corresponds to that of Art. 109 Paragraph 1 of the WRV. The prohibition of Article 3, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law to unequal treatment on the basis of selected characteristics was created under the impression of the systematic disadvantage and persecution of individual population groups under National Socialism. The establishment of the same position of men and women in a separate paragraph serves to concretise the prohibition of unequal treatment in Article 3 (3) of the Basic Law.

The constitutional text has so far been changed once since it came into force: By law of October 27, 1994 with effect from November 15 of the same year, Art. 3 Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law was supplemented by its second sentence, which obliges the state to actually enforce equality of Promote husband and wife. In addition, Article 3, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law has been supplemented by a further sentence that prohibits discrimination on the grounds of disabilities.

Guarantee of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG

According to Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG, all people are equal before the law. Unlike most of the other fundamental rights, Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law does not protect any particular sphere of freedom from sovereign interference . This is based on the fact that this fundamental right is not a freedom , but an equality right. Its guarantee can therefore only be derived from a comparison of several facts in relation to their treatment by the state. Art. 3 paragraph 1 GG obliges them to treat the same facts equally. The citizen can use this fundamental right to ward off unequal treatment violating this.

Personal scope

Art. 3 paragraph 1 GG does not restrict the group of protected persons. Therefore, the fundamental right protects everyone. This includes all natural persons . Whether associations of persons , in particular legal persons under private law, are protected by the basic right is judged on the basis of Article 19 paragraph 3 of the Basic Law. According to this, associations are protected which have their seat in Germany and to which the fundamental right is essentially applicable.

Public authorities are not protected by Article 3 paragraph 1 of the Basic Law. As part of state power, these are already bound by fundamental rights in accordance with Article 1, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law, so that they cannot at the same time represent fundamental rights holders. An obligation of equal treatment can, however, result from state organization law among sovereigns .

Material scope

Unequal treatment

The starting point for establishing a legally relevant unequal treatment lies in the formation of a comparison pair. Several facts can be compared if they have essentially similar characteristics in relation to one circumstance. This applies if they can be grouped under a common umbrella term. If, for example, students from the University of Bremen complain that the State of Bremen charges tuition fees and thereby privileges nationals, the nationals and non-nationals students come into question as comparison groups. These groups can be summarized under the heading of students at the University of Bremen , as this is a characteristic that members of both groups have. It is therefore a suitable comparison pair.

So that several facts can be compared within the framework of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG, they must be exposed to the access of the same public authority. This requirement arises from the fact that the duty of equal treatment binds every sovereign independently and independently of other sovereigns. Art. 3 GG therefore has no effect, for example, if a citizen complains that he is more severely liable for damage to public roads in one federal state than in other federal states due to state law. The same applies to the provision of civil servants , the scope of which may vary depending on the employer.

Legally relevant unequal treatment exists when a comparison group is disadvantaged compared to another with regard to a common characteristic. Legally relevant inequality of treatment lies, for example, in the graduation of kindergarten fees according to family income and in the graduation of tuition fees according to country of origin. The different application of a legal norm can also represent legally relevant unequal treatment. An unequal treatment can also lie in the deviation of an authority from a established practice, which achieves the quality of a self-binding of the administration .

Justification of unequal treatment

If there is unequal treatment, this can be justified. Art. 3 paragraph 1 GG does not contain any requirement under which conditions this is possible. The Federal Constitutional Court regards unequal treatment as lawful insofar as it is based on a viable factual reason. The conditions under which a material reason can bear unequal treatment is controversial in jurisprudence and science.

Arbitrary formula

The Federal Constitutional Court initially assumed that Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law merely prohibits arbitrary unequal treatment. It therefore considered unequal treatment to be justified if it was based on a ground of differentiation based on reasonable considerations. According to this, unequal treatment was only inadmissible if it did not appear justifiable from any point of view and was therefore arbitrary.

New formula

In a decision on preclusion in civil procedure law from 1980, the Federal Constitutional Court tightened its requirements for the reason for differentiation: It already assumed a violation of Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law if there was a difference in treatment of essentially the same, which was not based on sufficiently weighty factual reasons. Jurisprudence calls this test standard a new formula. This approach puts a balancing of interests at the center of the justification: while according to the arbitrary formula the existence of a factual reason was sufficient, the new formula requires that this reason is proportionate to the disadvantage of the individual.

The Federal Constitutional Court specified the new formula in later decisions. In doing so, it approached the principle of proportionality , which is of great importance in assessing the legality of encroachments on civil liberties. Using this standard, justifying unequal treatment presupposes that it has a legitimate purpose. This is a purpose that serves the common good or some other constitutional good. Furthermore, the inequality of treatment must be suitable to achieve this and represent the mildest, equally effective means. Finally, the inequality of treatment must be appropriate. This is true if it does not create a burden on the disadvantaged that is out of proportion to the legitimate purpose. Most important in practice is the assessment of the legitimate purpose and appropriateness.

Relationship of the formulas to each other

So far, the Federal Constitutional Court has not turned away from the arbitrary formula in its decisions, but applies both formulas in parallel. For this reason, the test criteria of the Federal Constitutional Court have so far varied, depending on the matter, from a purely arbitrary control to a comprehensive proportionality control.

The court tends to the stricter standard when the unequal treatment relates directly to persons. This applies, for example, to the distinction according to descent or origin or to the distinction between blue-collar workers and white-collar workers . The court also regularly applies the new formula if the unequal treatment is serious or affects the exercise of civil rights. For example, the court examined a Bremen regulation on tuition fees based on the new formula, since the burden of tuition fees is related to the freedom of occupation guaranteed by Art. 12 GG . The fact that national students only had to pay fees for a significantly higher number of semesters than foreigners assessed it as unconstitutional, as this burdened the non-national students in a disproportionate way for no material reason: fees serve as consideration for the use of administrative services. Whether the enrolled student is domiciled in Bremen has no effect on their scope. The court also used the new formula to control the grading of kindergarten fees based on family income. The court judged this to be fundamentally permissible, since fees do not have to be based solely on the principle of cost recovery, but can also be calculated on the basis of other factors. The fairness of taxes requires, however, that the fee does not cover the costs actually incurred and is in reasonable proportion to the consideration provided by the administration. The fee amount must therefore be based on the service provided and may not be calculated for the individual in such a way that he bears the burdens of other citizens.

A check only for arbitrariness is regularly applied when a public authority grants benefits. Even with the indirect third-party effect of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG in private law and in the case of purely factual unequal treatment, there is usually only a check for arbitrariness. Even in complex and extensive matters, the Federal Constitutional Court grants the legislature extensive scope for assessment so that its work is not impaired by too strict control. These matters include, for example, remuneration regulations in social law, measures to reorganize the state budget and salary regulations .

Finally, constitutional law can determine the yardstick against which unequal treatment is controlled. A low density of controls comes into consideration, for example, if the Basic Law specifies a differentiation. This happens, for example, in Article 33 (5) of the Basic Law, which grants civil servants a special legal status.

Areas of application of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG

legislative branch

The legislature can violate the principle of equality by issuing a norm that does not fit into the system of thematically related norms. The Federal Constitutional Court evaluates such a norm as an indication of a violation of Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law. Related to this is the requirement of consistency, which calls on the state to act conclusively. A violation of Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law therefore exists if state action is contradictory without there being a comprehensible reason for this. The requirement of consistency in tax law is of great importance .

In principle, the typing of facts is permitted, as this is often necessary in order to enact legal provisions. The Federal Constitutional Court considers this to be permissible as long as the legislature orients itself in the formulation of its norms on the normal case and does not cause any disproportionate disadvantage for individual groups.

executive

The executive is obliged by Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG to act consistently. It is therefore prohibited, for example, from the arbitrary exercise of discretionary powers . If, for example, an authority becomes aware of several similar violations of the law, it must deal with them systematically in a comprehensible manner and must not limit itself to taking action against individual violations for no apparent reason.

Another important area of application of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG is the self-commitment of the administration: If an administration maintains a certain decision-making practice over a longer period of time when exercising a margin of discretion , it may only deviate from this if there is a sound factual reason for this. The self-bonding may require an authority against a citizen to regulations must be observed. Basically, this is an internal right of the administration, which has no effect on the citizen. However, if an authority regularly observes such regulations, it establishes an administrative practice from which it may not deviate after some time without sufficient substantive reason. However, there is no protection of legitimate expectations in the case of illegal administrative action: If an authority makes multiple wrong decisions, a third party cannot, citing Article 3, Paragraph 1, of the Basic Law, demand that this mistake be committed again in his favor. For example, a citizen may not take action against the initiation of criminal proceedings on the grounds that other persons who have also violated a criminal norm were not prosecuted.

Judiciary

Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law obliges case law to apply the law equally. It is therefore inadmissible, for example, to refuse a promising appeal because of the workload of the appeal court.

The incorrect application of the law, on the other hand, does not fundamentally constitute a violation of Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law. The threshold for unjustified unequal treatment is only exceeded when a decision is no longer comprehensible from any point of view, i.e. it is made arbitrarily. The Federal Constitutional Court affirmed this, for example, in the case of a clear misinterpretation of a statement in the context of a legal process as well as in the case of the unfounded acceptance of a claim in contradiction to the highest court rulings. A binding of the courts to supreme court case law does not follow from Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG, however, since this would be incompatible with the independence of the judge guaranteed by Art. 97 Paragraph 1 GG.

Equal treatment

In addition to the equal treatment of the same facts, Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law requires, according to the prevailing view in jurisprudence, to treat unequal facts differently according to their individual character. This guarantee forbids the state to treat several different issues equally if this does not do justice to the peculiarities of at least one issue.

If different issues are treated equally, this is justified if there is a sound reason. What requirements are to be placed on this, as with the justification of unequal treatment, depends on the severity and consequences of the equal treatment.

The practical significance of the prohibition of nonsensical equal treatment is insignificant, since many equal treatment can also be interpreted as unequal treatment through the appropriate choice of comparison groups and the comparative factor.

Fundamental rights competitions

If the areas of application of several basic rights overlap in one issue, these are in competition with one another.

The general principle of equality in Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law is subsidiary to other rights of equality. This applies, for example, to the special prohibitions of differentiation in Art. 3 Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law and the right to equal treatment with regard to civil rights contained in Art. 33 Paragraph 1 and 2 of the Basic Law. For the equal treatment of candidates in Bundestag elections , Art. 38 Paragraph 1 GG is more special than the general principle of equality.

Since freedom rights pursue a different purpose than equality rights, these are in principle next to Article 3 paragraph 1 of the Basic Law. However, some civil liberties also contain an equality component. In such cases, Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law takes a back seat to the right to freedom if this is more closely related to the facts of the case. If the unequal treatment is, for example, a disadvantage of individual opinions, the freedom of expression protected by Art. 5 Paragraph 1 GG is usually more special. The same applies to the discrimination against religious communities, which falls under the protection of religious freedom ( Art. 4 GG).

In addition, the right of equality can be combined with civil liberties in order to construct new guarantees or strengthen existing ones. For example, the Federal Constitutional Court derives from the combination of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 and Art. 12 Paragraph 1 GG a right to equal access to study places within the framework of the existing capacities of the universities.

Legal consequences of a breach

If the Federal Constitutional Court finds that sovereign action violates the principle of equality, it declares this action to be unconstitutional. In the event of a violation of a right to freedom, this usually means that the encroachment on fundamental rights is declared null and void. If the general principle of equality is violated, however, the state has more leeway to create a constitutional state than it has if a right to freedom is violated. He can decide to treat one of the affected issues differently in the future or to treat all affected issues in a new way. Therefore, if the Federal Constitutional Court finds a violation of Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law, the state often sets a deadline within which it must remedy the constitutional violation. If the unequal treatment is based on a norm, this may no longer be applied until the violation has been remedied.

Guarantee of Art. 3 Paragraph 2, 3 GG

Paragraphs two and three of Article 3 of the Basic Law contain special equality rights that take precedence over the general principle of equality. Art. 3, Paragraph 3, Clause 1 of the Basic Law names several features that may only be used as differentiation criteria under strict conditions. These are sex, descent, race, language, homeland, origin, belief, as well as religious and political views.

The scope of application of Article 3, Paragraph 3, Clause 1 of the Basic Law is opened if a differentiation is made due to one of the listed features. The Federal Constitutional Court assessed the conditions under which a distinction is made based on a characteristic differently. Initially, it only classified targeted unequal treatment under Article 3, Paragraph 3, Clause 1 of the Basic Law. The court expressly abandoned this approach in its decision on the ban on night work for female workers. Since then, it has also measured such unequal treatment on the basis of Art. 3 Paragraph 3 Sentence 1 GG, in which the unequal treatment is not intended, but only occurs as a result of state action. The prevailing view in jurisprudence welcomes the Federal Constitutional Court's expanded understanding of the term, since the indirect impairment of civil liberties indisputably requires justification on the basis of the standards of the respective fundamental right, which is why it is consistent not to restrict oneself to direct abbreviations of fundamental rights in Art. 3 GG.

gender

Content of the differentiator

Art. 3 paragraph 3 GG forbids linking to gender. This prohibition covers all measures that treat women and men unequally. Both direct and indirect unequal treatment can be considered for this. A gender-neutral measure can also constitute unequal treatment because of gender if it actually discriminates or favors one gender. For example, the disadvantage of part-time work predominantly affects women, since this form of employment is predominantly carried out by women. Therefore, it is a matter of gender unequal treatment.

A special regulation with regard to the differentiation according to gender is contained in Article 3 paragraph 2 of the Basic Law. This states that men and women have equal rights. Whether this guarantee has an independent meaning alongside Article 3 (3) sentence 1 of the Basic Law is a matter of dispute in jurisprudence.

justification

Art. 3 paragraph 3 GG does not provide for any possibility of justifying unequal treatment on the basis of one of the criteria mentioned. The justification for such unequal treatment can therefore only result from conflicting constitutional law. This possibility of restriction is based on the fact that constitutional provisions, as rights of equal rank, do not displace one another, but are brought into a relationship of practical concordance in the event of a collision .

Article 12a of the Basic Law, for example , which expressly provides that only men are obliged to serve in the military, is a conflict of constitutional law . If the Basic Law does not explicitly allow unequal treatment according to Article 3 Paragraph 3 Clause 1 of the Basic Law, its legality is largely judged on the basis of the principle of proportionality.

Article 3, paragraph 2, sentence 2 of the Basic Law can constitute further conflicting constitutional law. According to this, the state promotes the actual implementation of equality between women and men and works towards eliminating existing disadvantages. This provision gives a right to the establishment of equal relationships, which can result in an obligation for the state to prefer one sex. The extent to which this obligation exists is controversial in jurisprudence. There is agreement to the extent that the state is required to guarantee equal opportunities between men and women. In addition, some voices assume that Article 3, Paragraph 2, Sentence 2 of the Basic Law also aims to achieve equality of results, because this provision represents a collective right of women that ensures comprehensive equality. Against this it is argued that the concept of a collective basic right is alien to the Basic Law. In this context, legal disputes arise particularly in relation to quotas for women . These not only represent a direct disadvantage because of gender, but are also in tension with Art. 33 Paragraph 2 GG in the award of public offices. This standard obliges the state to focus exclusively on suitability, competence and professional performance when assigning offices. Equality issues are influenced to a large extent by European law. According to European and German case law, such quotas are permissible if they are only used in cases in which female and male applicants are equally qualified. In this case there is no conflict with Article 33, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law, since the criteria mentioned do not permit a clear decision, so that further selection criteria must be used. The preference for women is justified in this case if the proportion of women within the relevant group is below 50%. However, a quota regulation must contain an opening clause that allows a woman not to be given preference if there are reasons in the person of the male applicant to employ him.

Finally, gender-related inequality of treatment is permitted, which is absolutely necessary for an appropriate regulation because it is linked to biological differences. This can be used to justify protective provisions in favor of pregnant women, for example. In contrast, the Federal Constitutional Court assessed the night work ban for female workers as unconstitutional.

ancestry

The trait of ancestry relates to a person's ancestors. Its inclusion in the catalog of Article 3, Paragraph 3, Clause 1 of the Basic Law, for example, prohibits family liability , which was applied under National Socialism .

race

The characteristic of race prohibits the unequal treatment of people due to their outdated classification into races . This feature was included in Article 3, Paragraph 3, Clause 1 of the Basic Law in order to avoid racial discrimination, as occurred during the National Socialist era. The use of the term race is criticized because it is part of a racist terminology and arouses associations with outdated biological concepts.

language

The language criterion prohibits unequal treatment of people on the basis of their mother tongue. This criterion serves to protect minority languages, such as Danish and Sorbian .

Home and origin

The differentiating features of home and origin are related to one another in terms of content. The former is linked to a person's geographical origin, i.e. their place of birth. The latter characteristic relates to a person's social origin.

Beliefs and beliefs

Finally, Article 3, Paragraph 3, Clause 1 of the Basic Law prohibits unequal treatment based on beliefs or beliefs of a religious or political nature. These differentiating features are of little relevance because they are the subject of civil liberties. Faith and worldview are protected by Art. 4 GG, political views are protected by the basic communication rights of Art 5 GG.

disability

Finally, Article 3, Paragraph 3, Sentence 2 of the Basic Law prohibits discrimination because of disabilities. The Federal Constitutional Court defines the term disability as the consequence of a not only temporary functional impairment, which is based on an irregular physical, mental or emotional condition. Prohibited discrimination occurs when the living situation of a disabled person deteriorates as a result of a sovereign measure compared to people without disabilities. In this respect, for example, the exclusion of deaf-mutes unable to write from the possibility of drawing up a will violated by the formal requirements under inheritance law. However, if a person lacks the ability to exercise a right due to his or her handicap, the denial of this right does not constitute a violation of Article 3 (3) sentence 2 of the Basic Law.

Article 3, Paragraph 3, Sentence 2 of the Basic Law obliges the legislature to consider disabled people. Therefore, this guarantee, in combination with other fundamental rights, can oblige the state to enable disabled people to exercise their freedoms. For example, the Federal Constitutional Court derived from the general freedom of action (Art. 2 Paragraph 1 GG) and Art. 6 Paragraph 2 Clause 1 GG in conjunction with Art. 3 Paragraph 3 Clause 2 GG the duty of the state to ensure that disabled people have access to public education can perceive.

Adding a sexual identity feature

For years, LGBTI associations such as the LSVD and LGBTI activists have been demanding that Article 3 of the Basic Law be supplemented with the feature of sexual identity . This demand is supported by the political parties Die Linke , Bündnis90 / Die Grünen and the Free Democratic Party across all parties . This reform is generally supported by the Social Democratic Party of Germany , but it is bound by coalition agreements with the Christian Democratic Union of Germany .

Reception in the television film

The original formulation of Article 3 (2) with just five words “Men and women have equal rights” is based on the special initiative of Parliamentarian Elisabeth Selbert . The film Sternstunde seine Leben , which was shown on German television in 2014, is a reminder of their activities in this regard in the Parliamentary Council , in which, however, at the end Adenauer anachronistically announces the version changed in 1994, not the original version enforced by Selbert.

literature

- Joachim English: Art. 3 : In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- Werner Heun: Art. 3 . In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume I: Preamble, Articles 1-19. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck 2013, ISBN 978-3-16-150493-8 .

- Hans Jarass: Art. 3 . In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 . In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- Rupert Scholz: Art. 3 . In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

Web links

- Art. 3 GG on dejure.org - legal text with references to case law and cross-references.

Individual evidence

- ↑ https://lexetius.com/GG/3,2

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 1b. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Werner Heun: Art. 3 , Rn. 70-71. In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume I: Preamble, Articles 1-19. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck 2013, ISBN 978-3-16-150493-8 .

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 13. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Christian Starck: Art. 3 , Rn. 294. In: Hermann von Mangoldt, Friedrich Klein, Christian Starck (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law. 6th edition. tape 1 . Preamble, Articles 1 to 19. Vahlen, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-8006-3730-0 .

- ↑ BAG, judgment of February 21, 2013, 6 AZR 539/11 = New Journal for Labor Law Case Law Report 2013, p. 296.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 12. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Johannes Dietlein: The doctrine of the fundamental rights to protect . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-428-07342-8 , pp. 84 .

- ↑ Uwe Kischel: Art. 3 , Rn. 91. In: Beck'scher Online Comment GG , 34th Edition 2017.

- ↑ Rupert Scholz: Art. 3 , Rn. 512. In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (Ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 1. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 765-767.

- ↑ Joachim English: Art. 3 , Rn. 2. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 1. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 1. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Joachim English: Art. 3 , Rn. 3. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ BGBl. 1994 I p. 3146 .

- ↑ Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 225 In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ a b BVerfGE 42, 64 (72) : Foreclosure auction.

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 770.

- ↑ Jörn Ipsen: Basic rights . 20th edition. Verlag Franz Vahlen, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-8006-5527-4 , Rn. 797.

- ↑ Michael Sachs, Christian Jasper: The general principle of equality . In: Juristische Schulung 2016, p. 769 (770).

- ↑ BVerfGE 49, 148 : Contact block.

- ↑ Werner Heun: Art. 3 , Rn. 18. In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume I: Preamble, Articles 1-19. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck 2013, ISBN 978-3-16-150493-8 .

- ↑ Thorsten Kingreen, Ralf Poscher: Fundamental rights: Staatsrecht II . 32nd edition. CF Müller, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8114-4167-5 , Rn. 487.

- ↑ BVerfGE 134, 1 (20) : Tuition fees Bremen.

- ↑ BVerfGE 130, 151 (175) : Assignment of dynamic IP addresses.

- ↑ Michael Sachs, Christian Jasper: The general principle of equality . In: Juristische Schulung 2016, p. 769 (771).

- ↑ BVerfGE 42, 20 (27) : Public road property.

- ↑ BVerfGE 106, 225 (241) : Eligibility of optional benefits I.

- ↑ Thorsten Kingreen, Ralf Poscher: Fundamental rights: Staatsrecht II . 32nd edition. CF Müller, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8114-4167-5 , Rn. 490.

- ↑ BVerfGE 97, 332 : Kindergarten contributions.

- ↑ BVerfGE 134, 1 : Tuition fees Bremen.

- ↑ a b Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 118. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of December 19, 2012, 1 BvL 18/11 = Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 2013, p. 1418 (1419).

- ^ Lothar Michael, Martin Morlok: Grundrechte . 6th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2017, ISBN 978-3-8487-3871-7 , Rn. 784.

- ↑ BVerfGE 1, 14 (52) : Südweststaat.

- ↑ BVerfGE 10, 234 (246) : Platow amnesty.

- ↑ BVerfGE 55, 72 (88) : Preclusion I.

- ^ Lothar Michael, Martin Morlok: Grundrechte . 6th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2017, ISBN 978-3-8487-3871-7 , Rn. 785.

- ↑ Jörn Ipsen: Basic rights . 20th edition. Verlag Franz Vahlen, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-8006-5527-4 , Rn. 808

- ↑ Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 14. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 107, 27 (46) : Double housekeeping.

- ↑ BVerfGE 117, 272 (301) : Employment Promotion Act.

- ^ Friedhelm Hufen: Staatsrecht II: Grundrechte . 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69024-2 , § 39, Rn. 16.

- ↑ Jörn Ipsen: Basic rights . 20th edition. Verlag Franz Vahlen, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-8006-5527-4 , Rn. 182-195.

- ^ Marion Albers: equality and proportionality . In: Juristische Schulung 2008, p. 945 (947).

- ↑ Michael Sachs, Christian Jasper: The general principle of equality . In: Juristische Schulung 2016, p. 769 (772).

- ↑ BVerfGE 90, 46 (56) : termination.

- ↑ BVerfGE 107, 27 (45) : Double housekeeping.

- ↑ BVerfGE 134, 1 (22) : Tuition fees Bremen.

- ↑ BVerfGE 97, 332 (345) : Kindergarten contributions.

- ↑ BVerfGE 97, 332 (346) : Kindergarten contributions.

- ↑ BVerfGE 122, 1 (23) : Agricultural market aid.

- ↑ BVerfGE 116, 135 (161) : Equality in public procurement law.

- ↑ BVerfGE 70, 1 (34) : Orthopedic technician guilds.

- ↑ BVerfGE 60, 16 (43) : hardship compensation.

- ↑ BVerfGE 81, 156 : Employment Promotion Act 1981.

- ^ Anna Leisner: Continuity as a constitutional principle: With special consideration of tax law . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147695-6 , p. 234 .

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 181, Rn. 219.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 29. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 112, 268 (280) : Childcare costs.

- ↑ BVerfGE 117, 1 (31) : inheritance tax.

- ↑ Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 116-117. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ OVG NRW, judgment of February 20, 2013, 2 A 239/12 = New Journal for Administrative Law, Case Law Report 2013, p. 678.

- ↑ BVerwG, judgment of April 23, 2003, 3 C 25.02 = Neue Zeitschrift für Verwaltungsrecht 2003, p. 1384.

- ↑ BVerfGE 50, 142 (166) : breach of maintenance obligation.

- ↑ BVerfGE 9, 213 (223) : Therapeutic Products Advertising Ordinance.

- ↑ BVerfGE 101, 239 (269) : due date regulation.

- ↑ BVerfGE 71, 354 (362) .

- ↑ BVerfGE 54, 277 (293) : Rejection of the appeal.

- ↑ BVerfGE 75, 329 (347) : Administrative accessory in environmental criminal law.

- ↑ BVerfGE 96, 189 (203) : Fink.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of March 18, 2005, 1 BvR 113/01 = Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 2005, p. 2138.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of June 30, 2011 - 1 BvR 367/11 = Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 2011, p. 3217.

- ↑ Lerke Osterloh, Angelika Nußberger: Art. 3 , Rn. 128. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 110, 141 (167) : Attack dogs.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 8. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 1, 208 (237) : 7.5% blocking clause.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 2-2a. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 65, 104 (112) : Maternity Allowance I.

- ↑ BVerfGE 64, 229 (238) : inspection of the land register.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 3. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 771.

- ↑ BVerfGE 33, 303 : Numerus clausus I.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 3 , Rn. 40. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 126, 268 (284) : Domestic study.

- ↑ BVerfGE 73, 40 (101) : Party donation judgment.

- ↑ BVerfGE 105, 73 (134) : Pension taxation.

- ↑ BVerfGE 19, 119 (126) : Coupon tax.

- ↑ BVerfGE 75, 40 (69) : Private school financing.

- ↑ BVerfGE 39, 334 (368) : Extremist decision.

- ↑ BVerfGE 85, 191 (206) : Night work ban.

- ↑ Heike Krieger: Art. 3 , Rn. 60. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ Alexander Tischbirek, Tim Wihl: Unconstitutionality of "Racial Profiling". In: JuristenZeitung 2013, p. 219 (223).

- ↑ BVerfGE 121, 241 (254) : supply discount.

- ^ Konrad Hesse: Basic features of the constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany . 20th edition. CF Müller, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8114-7499-5 , Rn. 72.

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 840.

- ↑ a b Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 850

- ↑ ECJ, judgment of October 17, 1995, C-450/93 = Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 1995, p. 3109.

- ↑ ECJ, judgment of November 11, 1997, C-409/95 = Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 1997, p. 3429.

- ↑ Kyrill Schwarz: Basic cases to Art. 3 GG . In: Juristische Schulung 2009, p. 417 (421).

- ↑ BVerfGE 85, 191 (207) : Night work ban.

- ↑ BVerfGE 92, 91 (109) : Fire Department Tax.

- ↑ BVerfGE 85, 191 : Night work ban.

- ↑ BVerfGE 9, 124 (128) : Poor Law.

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 830.

- ↑ Heike Krieger: Art. 3 , Rn. 79. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ Hendrik Cremer: A Basic Law without "Race": Proposal for an amendment to Article 3 Basic Law . tape 16 , 2010 ( ssoar.info [accessed September 14, 2019]).

- ↑ Heike Krieger: Art. 3 , Rn. 81. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 102, 41 (53) : Basic pension for disabled people .

- ↑ BVerfGE 48, 281 (288) : Damaged basic pension.

- ↑ Uwe Kischel: Art. 3 , Rn. 222. In: Beck'scher Online Comment GG , 34th Edition 2017.

- ↑ Heike Krieger: Art. 3 , Rn. 85. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 96, 288 (301) : Integrative schooling.

- ↑ BVerfGE 96, 288 (302) : Integrative schooling.

- ↑ BVerfGE 99, 341 : Exclusion of a deaf-mute will.

- ↑ BVerfGE 99, 341 (357) : Exclusion of a deaf-mute will.

- ↑ BVerfGE 96, 288 (304) : Integrative schooling.

- ↑ LSVD.de: Article 3 of the Basic Law

- ↑ Queer.de: Opposition starts a joint attempt to supplement Article 3 , accessed on May 21, 2019