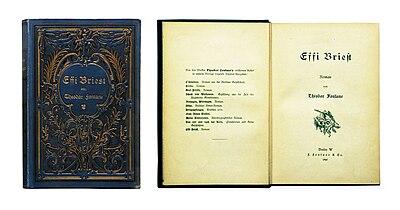

Effi Briest

Effi Briest is a novel by Theodor Fontane that was published in six episodes in the Deutsche Rundschau from October 1894 to March 1895 , before being published as a book in 1896. The work is considered to be a climax and turning point of poetic realism in German literature: a climax because the author combines critical distance with great literary elegance; A turning point, because Fontane became the most important midwife of the German social novel , which a few years later was to achieve world renown for the first time with Thomas Mann's novel Buddenbrooks . Thomas Mann owes numerous suggestions to Fontane's style. The Buddenbrooks family name also comes with high probability from Effi Briest : In chapter 28 a person named Buddenbrook is mentioned.

It describes the fate of Effi Briest, who at the age of seventeen married the Baron von Innstetten, who was more than twice her age, at her mother's advice. He not only treats Effi like a child, but neglects her in favor of his career-enhancing business trips. Lonely in this marriage, Effi enters into a fleeting love affair with an officer. When Innstetten discovered his love letters years later, he was unable to forgive Effi. Compulsively arrested in an outdated code of honor, he kills the ex-lover in a duel and gets a divorce. Effi is now socially ostracized and is even ostracized by her parents. Only three years later are they ready to take the meanwhile terminally ill Effi again.

In legal history , the novel reflects the harsh consequences with which violations of the bourgeois moral code were punished in the Wilhelmine era .

content

(The page numbers in the following sections refer to the edition of the novel published below by Goldmann-Verlag .)

The 38-year-old Baron von Innstetten, a former admirer of Effi's mother, holds the 17-year-old girl's hand at the beginning of the novel and moves with Effi, after the marriage and subsequent honeymoon through Italy, to Kessin (fictitious) in Western Pomerania . Effi is never really happy there and suffers from her fear of an alleged ghost in the spacious country house: She is convinced that some nights a Chinese who once lived in Kessin and who is said to have come to a strange end will appear. Effi is strengthened in this fear by Innstetten's housekeeper Johanna. Effi finds comfort and protection only with Rollo, Innstetten's dog, who accompanies her on her lonely walks.

Effi also becomes friends with the pharmacist Alonzo Gieshübler, who understands and adores her and gives her support. She receives carefully prepared newspapers and small gifts from him every day, which are intended to enrich her uneventful life, a need that is hardly satisfied by the formal country parties and modest visits in which she takes part with her husband. On the contrary: the young lady is bored to death in the stiff aristocratic circles (98).

Nine months after the wedding, Effi had a daughter, who was baptized Annie. During her pregnancy, Effi met the Catholic housemaid Roswitha on one of her walks, whom she is now hiring as a nanny. At about the same time, Major von Crampas appears in Kessin. He served in the military together with Innstetten, but his character is quite the opposite: a spontaneous, easy-going and experienced "woman's man". Married to a jealous, "always disgruntled, almost melancholy" woman (101), he is enthusiastic about Effi's youthful naturalness and encourages her to change and be careless. At first Effi resists his charm, but then when Effi is repeatedly left alone by Innstetten and feels frightened and lonely in her own house, a secret affair begins that will plunge Effi into ever more pressing conflicts of conscience: Effi lets herself go first To persuade Crampas to pass the long winter evenings by rehearsing a joint play with the significant title "A Step From the Path" ( Ernst Wichert ) and to perform it in the Kessiner Ressource. Shortly before Christmas, there was an extremely successful performance under the direction of Major Crampas, and Effi was celebrated as a female heroine - admired by men, envied by women. A week later, the Kessiner dignitaries go on a traditional sleigh ride to the head forester's house. When you start your way home at night, already a little tipsy, the horses suddenly strike on the so-called Schloon, an underground watercourse that has made the beach impassable. To avoid the sledges sinking into the treacherous sand, you have to take a detour through the dark forest along the banks and drive “through the middle of the dense forest” (156). Crampas, who has taken a seat in the last sled with Effi, takes advantage of the protection of darkness: Effi “was afraid and at the same time was under a spell and didn't want to leave. - 'Effi', it now sounded softly in her ear, and she heard that his voice was trembling. Then he took her hand and loosened the fingers that were still closed and covered them with hot kisses. It was as if she were going to faint. "(157)

From now on, the two meet regularly in the dunes, and Effi is forced to play a "comedy" for her husband. She feels “like a prisoner”, suffers heavily and wants to free herself: “But although she was capable of strong feelings, she was not a strong nature; she lacked sustainability and all good ideas passed away again. So she drove on, today because she couldn't change it, tomorrow because she didn't want to change it. The forbidden, the mysterious had his power over them. ”(164)

When, weeks later, her husband was called to Berlin to pursue a career in the ministry, and Innstetten proudly announced that they would soon be leaving Kessin and moving to the capital , Effi feels a huge relief: "Effi didn't say a word, and only her eyes got bigger and bigger; there was a nervous twitch around the corner of her mouth and her whole delicate body trembled. Suddenly she slipped down from her seat in front of Innstetten, clutched his knees and said in a tone as if she were praying: 'Thank God!' "(176) - Finally relieved of all remorse, Effi" enjoys her new life “In the big city, where she can soon forget the boring time in rural Kessin and the forbidden relationship with Crampas.

Six years later, while Effi is in Bad Ems for a cure , Innstetten accidentally discovers Crampas' letters in a sewing box that reveal the affair between the two of them. Due to the code of honor - from Innstetten's point of view critical, but still regarded as socially binding - he decides to challenge the major to a duel . Effi's former lover is fatally hit. Despite all self-doubts, Innstetten separates from his wife and knows that he is also destroying his own private happiness: "Yes, if I had been full of deadly hatred, if I had felt a deep sense of revenge here ... Revenge is nothing beautiful, but something human and has a natural human right. But as it was, everything was for the sake of an idea, for the sake of a term, was a made-up story, half a comedy. And now I have to continue this comedy and have to send Effi away and ruin her and me too. "(236)

Effi's parents send their daughter a letter in which she learns that, due to social conventions, she can no longer return to Hohen-Cremmen, the parental home and house of her happy childhood. Disapproved by her husband and parents, she moves into a small apartment in Berlin and leads a lonely existence there, together with the housekeeper Roswitha, who is still loyal to her, and who has been cast out of her social sphere.

After a disappointing visit by her little daughter Annie, who was not allowed to see her mother for a long time and is now completely estranged from her, Effi suffers a breakdown. On the advice of the doctor treating Effi, her parents decide to take their sick daughter back into the home. Effi's health improves only briefly. In view of the approaching death, she expresses understanding for the actions of her former husband (285). Effi Briest dies in her parents' house at the age of 30. Effi's mother believes she is partly to blame for the death of her daughter because she advised Effi to marry a man 21 years older than her early. Herr von Briest, however, ends any further brooding with his leitmotif throughout the novel: "Oh, Luise, let ... that is 'too' a field."

shape

(The page numbers in the following sections refer to the edition of the novel published below by Goldmann-Verlag.)

What distinguishes Fontane's work, among other things, is his tension-creating juggling with the aestheticizing elements of poetic realism on the one hand and the means of bourgeois social romance that strive for greater objectivity on the other. In addition, he virtuously pulls out all the stops of literary narration: from authorial conversational tone to perspective reports with a changing focus to experienced speech , from epic descriptions to dialogical conversation to monological letter form - no means of conventional literary writing remains unused. "The network of references through relational images and counter-images, allusions and parallels, omina , signals, echoes and reflections, repetitive, abbreviated image and speech formulas - Fontane uses them both thoughtfully and deliberately."

Father Briest is in many ways Fontane's alter ego in the novel, in particular, applies it for his parable: "This is a (too) wide field." Which the dictum has become. It has a key function in that Fontane not only makes it a recurring leitmotif , but also the crowning final sentence of his novel. To old Briest this world seems too complicated, too contradictory and too annoying to want to explain. With his quote he (and his author) always leaves open how he feels about things and leaves out what every reader should add for himself.

Effi is too young, too naive, too unbridled; Innstetten is too old, too addicted to a career, too jealous, too humorless and too humorous; the two are too different. While Fontane wants to point out a weakness of the old Briest by choosing the formulation “too far”, on the other hand he emphasizes the liberal tolerance and humanity of this father figure by dispensing with any further explanation. But whenever love and humanity are in demand, for example when it comes to bringing the socially ostracized and outcast daughter back home against the "demands of society", the old Briest is quite willing to get out of his cover and his reserve to give up, even against the resistance of his wife: “Oh, Luise, come to me with the catechism as much as you want; but don't come to me with 'society' [...] 'society', if it only wants to, can turn a blind eye. [...] I will simply telegraph: 'Effi, come.' ”(269 f.) With his rebellion and the demand to turn a blind eye, he behaves decidedly more courageous than his wife, who rejected her daughter mainly because because she thought she had to “show her colors before all the world” (248). Nevertheless, it is true of old Briest that, paradoxically, it is precisely his reticence that, like the pharmacist Gieshübler, makes him one of the defining characters of the novel, although only marginalized.

In the same way, various other main motifs of the novel owe their charm to such gaps : the affair with Crampas, the question of guilt, the criticism of Prussian society and, last but not least, the mystery of the Chinese - all of them are never explicit, but almost exclusively in omissive hints and only in this way gain the suspenseful state of suspension that distinguishes the novel from trivial salon literature.

Symbols and motifs

(The page numbers in the following sections refer to the edition of the novel published below by Goldmann-Verlag.)

All the central themes of the novel (love, marriage, career, fear, guilt, renunciation, punishment, time and death) can be heard unmistakably in the first chapter (pp. 5–13), the most noticeable symbols of things (the roundabout, the churchyard wall, the Swing, the pond and the old plane trees) even in the first paragraph of the novel, where Fontane describes in detail the "Hohen-Cremmen mansion, which has been inhabited by the von Briest family since Elector Georg Wilhelm" with its "small ornamental garden" and so for one The density of images that he continually spins out over the course of his novel into a complex texture of forward and backward references and which gives his older work that sophisticated quality that the lightness of his narrative tone seems to know nothing of.

The roundabout

Even before Effi's wedding, the roundabout in the Hohen-Cremmen garden was given a referential function: “The heliotrope standing in a dainty bed around the sundial was still in bloom, and the gentle breeze that went carried the scent away to them [mother and daughter Briest ] across. 'Oh, how good I feel,' said Effi, 'so good and so happy; I can't imagine heaven more beautiful. And in the end, who knows whether they have such beautiful heliotrope in heaven. '”This comparison makes the idyll of Hohen-Cremmen into an almost unearthly,“ almost otherworldly landscape. ”As the heliotrope (Greek“ solstice ”) longs for Effi always looks for the sunny side of life, a need that her parents take into account even after her death when they remove the sundial in the middle of the roundabout and replace it with Effi's tombstone, but "spare" the heliotrope around the former sundial and let the white marble slab "frame" (286). In this way, the roundabout also serves “the symbolic entanglement of life and death”, which also determines the majority of Fontane's other leitmotifs (see below).

The plane trees

"Between the pond [see below 'water metaphors'] and the roundabout and the swing [see below], half-hiding stood a couple of mighty old plane trees" (5). When a little later old Briest and his new son-in-law are walking “up and down the gravel path between the two plane trees” and talking about the future of Innstetten's professional life, it is already clear that these giant trees represent tradition and official life. Closing the garden on its open side and “standing slightly to the side” (14), they contrast with Effi's childhood and private life (swing or roundabout). As if from a certain distant height, they accompany your résumé and literally cast a broad shadow over your happiness. When it comes to Effi's wedding anniversary and she sits at the open window at night and cannot forget her guilt, “she put her head in her arms and wept bitterly. When she straightened up again, she had calmed down and was looking out into the garden again. Everything was so quiet, and a soft, fine sound, as if it was raining, hit her ear from the plane trees. […] But it was only the night air that left. ”(213) But at the same time“ the night air and the mist that rose from the pond ”, towards the end of the novel“ threw them onto the sick bed ”(283) and ultimately theirs Cause death, that incessant soft tone of the two plane trees sounds like the distant death song of seductive sirens that lure the young woman into the realm of the dead. On her last night, Effi sits down again at the open window, “to take in the cool night air again. The stars flickered and not a leaf moved in the park. But the longer she listened, the more clearly she heard again that it fell like a fine trickle on the plane trees. She felt a sense of liberation. 'Rest, rest.' "(286)

The swing

The old play equipment, "the posts of the beam position already a bit crooked", symbolizes not only Effi's carefree childhood in her parents' mansion in Hohen-Cremmen, but also the charm of the dangerous, the feeling of falling down and being caught again and again, which she loved to savor become. Her mother also thinks that she “should have been an art rider. Always in the trapeze, always daughter of the air ”(7), with which Fontane possibly alludes to Pedro Calderón de la Barca's drama La hija del aire ( The daughter of the air , 1653).

She does not know fear, on the contrary, "I fall at least two or three times a day and I have not yet broken anything" (9). Her friend Hulda of the same age reminds her of the saying "Arrogance comes before the fall", again symbolically and not entirely wrongly, if you consider that Effi has a pronounced weakness for everything "elegant" and not the unloved Geert von Innstetten finally marries because he is a baron and district administrator. Effi wants to aim high in the truest sense of the word, but only because her mother persuades her: "If you don't say no, [...] at twenty you are where others are at forty" (16). Her father promised her a climbing mast, “a mast tree, right here next to the swing, with a lawn and a rope ladder. Truly, I should like that, and I would not let myself be taken away from putting on the pennant above ”(13). Basically, Effi remains naive and undemanding - in complete contrast to the ambitions of Innstetten, who “with a 'true beer zeal” (11) pursues the “climbing higher up the ladder” (277) of his career.

The author also pursues another goal with his rocking symbol: “Anyone who, according to Fontane, necessarily strives towards the infatuations of such weightlessness according to his deepest nature, cannot rightly be found guilty. Effi succumbs "[when she chases after the other sledges" in flight "(156) on the nightly sleigh ride and is seduced by Crampas for the first time (157)]" in a moment of sweet shuddering beyond conscious responsibility; therefore it can lay claim to mitigation reasons. Effi's nature, in whose drawing the flight motif plays such a decisive role, is at the same time her apology. Since Fontane, within the literary conventions of a 'realistic', i. H. 'Objectively' presented events must not appeal directly to the reader, he pleads metaphorically. "

Later, by swinging weightlessly, Effi fulfilled her wish to be able to playfully climb over all difficulties and fly away. This desire eventually becomes so strong that the initial symbol of their childlike lust for life ultimately serves to embody their longing for death. Still facing her own end, she jumps onto the rocking board “with the agility of her youngest girlhood”, and “a few more seconds, and she flew through the air, and holding herself with only one hand, she tore herself with the other a small silk scarf from breast and neck and waved it as if in happiness and arrogance […] 'Oh, how beautiful it was, and how good the air was; I felt as if I were flying into the sky. '"(273)

The Chinese

The Chinese, according to Fontane “a turning point for the whole story”, is one of the noticeably large numbers of exotic figures from Kessin, whom Innstetten introduces to his newlywed wife before they arrive in their new home and who ensure that Effi belongs to that remote world the Baltic Sea on the one hand "extremely interested", but on the other hand very insecure from the start: the Pole Golchowski, who looks like a starost , but is in truth a "disgusting usurer" (42); the Slavic Kashubians in the Kessin hinterland; the Scot Macpherson; the barber Beza from Lisbon; the Swedish goldsmith Stedingk; and the Danish doctor Dr. Hannemann. Even Innstetten's loyal dog Rollo, a Newfoundland dog (45), and the pharmacist Alonzo Gieshübler with his "strange-sounding first name" (48) join this series of international extras.

However, the former owner of the Innstetten house, the South Sea captain Thomsen, who once brought a Chinese servant to Western Pomerania from his pirate voyages near Tonkin, plays a prominent role among them . Its mysterious story tells of the friendship between the two and of the fact that Thomsen's niece or granddaughter Nina, when she was about to be married, also danced with a captain on the wedding evening with all of the guests, “most recently with the Chinese. Suddenly it was said that she was gone, namely the bride. And it really was gone, somewhere, and nobody knows what happened there. And after a fortnight the Chinese died “and was given a grave between the dunes. “He could have been buried in the Christian churchyard because the Chinese were very good and just as good as the others.” (82) Like so many things, it remains open whether it is a happy or an unhappy one Love story (169) acted. What is certain is that it was also about a forbidden affair and that it anticipates a central aspect of the romance.

How much Innstetten, who actually only wants to familiarize Effi with the Kessin people and their surroundings, achieved the opposite with his stories and made her new home “scary” for his wife in this way, is additionally emphasized by the fact that Effi is the Chinese in literally "dances upside down" in the coming weeks. Her bedroom is exactly under the large loft where the conscious wedding ball once took place and whose curtains, moved by the wind, drag across the dance floor every night, reminding the sleepless Effi of the young bride, the Chinese and their tragic end. Since Innstetten, despite Effi's pleading, is not ready to simply cut off the “far too long” curtains like an old pigtail, the suspicion that he is deliberately using this ghost as a “means of education” that “like a” in the frequent absence of the landlord is confirmed Cherub with the Sword ”watches over the virtues of his young wife and, as“ a kind of fear machine based on calculation ”, ensures that Effi becomes more and more anxiously dependent on the protection of her husband and eagerly awaits his return.

If you add the rest of the gloomy furniture of the house and its ghostly inventory - the strange shark, which hangs as a "gigantic monster" swaying on the hall ceiling, the stuffed crocodile and, last but not least, the superstitious Mrs. Kruse with her "black chicken" - that is how it becomes understandable how uncomfortable her new home must appear to Effi and how much it becomes a "haunted house" (234) for her from the very first moment. But Innstetten can only understand and understand that when his marriage has already failed and he and his friend Wüllersdorf return to Kessin because of the duel: “[...] then the way inevitably led past Innstetten's old apartment. The house was even quieter than before; The ground floor looked rather neglected; how could it be up there! And the feeling of the uncanny that Innstetten had so often fought against or even laughed at at Effi, now it overcame him himself, and he was happy when it was over. "(233 f.)

The water metaphor

Like rocking, climbing and flying, Fontane also uses his water metaphors primarily to illustrate Effi's carefree passion. She is the high-spirited "child of nature" (35), who disregards everything artificial and artificial, everything lady-like and valuable to a lady, but unconditionally affirms everything living and natural and in it "includes death as a complement to life, even as a condition of its value ". Therefore, there is also a pond "close by" the swing and not far from the small roundabout, which will later be Effi's grave, which will form the gardens of Hohen-Cremmen, together with the "mighty old plane trees" - also unmistakable livelihoods Death symbols, which Fontane uses several times as leitmotifs - rounded off on the open side of his horseshoe shape.

While this rather idyllic body of water, in keeping with the ideal world of Hohen-Cremmens, opens the round of water metaphors at the beginning of the novel (5) in a rather harmless way, just a few pages later it becomes clear that the home pond and that of the lake become more and more decisive in the course of the novel evolving scenery of the "wild sea" are definitely related to each other. It is still child's play when Effi and her three friends let their leftover gooseberry shells (in a bag weighted with a pebble as a coffin) solemnly "slide slowly down into the pond" and thus "bury them in the open sea" (12). But Fontane's nod to the reader with the fence post - Effi: "This is how poor, unhappy women used to be sunk from a boat, of course because of infidelity" (13) - would not be necessary to recognize how the author was already here alludes to the problematic of his actual romantic

theme with the theatrical and ceremonial "sinking guilt" (12): Immediately before her adultery, on the way back from Uvagla along the beach, Effi is admonished by Sidonie not to lean too far out of the sled, and replies: “'I don't like the protective leather; they have something prose about them. And then, if I fly out, I'd be fine, preferably straight into the surf. Of course, a somewhat cold bath, but what does it matter ... '”And the next moment Effi imagines that she“ heard the mermaids sing ”(152). “The essential component symbolized by the two symbolic areas of water and air (swing) becomes for Effi the medium of her debt. But since these symbols appear as part of the idyllic district of Hohen-Cremmen and since this district has a referential function for Effi's death, that trait is also represented as a remedy [remedy] for guilt. "

How lust for life and longing for death merge, Fontane also makes clear with the aforementioned motif of “sinking”, which, mostly as an intransitive “sinking”, anticipates Effi's downfall in a very varied way. At first, allusions of this kind happen again in a harmless, even banal-comical way, namely when, for example, the life artist Trippelli, "strongly masculine and of a decidedly humorous type", gives Effi her all too soft "sofa pride of place" during a sociable evening in the Gieshüblers house: “I now ask you, madam, to accept the burdens and dangers of your office. Because of dangers - and she pointed to the sofa - it will probably be possible to speak in this case. [...] This sofa, which was born at least fifty years ago, is still built according to an old-fashioned sinking principle, and whoever trusts it [...] sinks into the abyss ”(86f.). Later, however, in the immediate vicinity of the first love scene with Crampas, the images become more threatening and full of allusions. When it comes to avoiding the dreaded "Schloon" on the beach, in which the sledges of those returning home threaten to sink, Effi asks: "Is the Schloon an abyss or something in which one has to perish with man and mouse?" And it is explained that the Schloon is “actually just a meager trickle” in summer, but in winter “the wind pushes the sea water into the small trickle, but not in a way that you can see it. And that's the worst of it, that's where the real danger lies. Everything happens underground and the whole beach sand is then permeated and filled with water deep down. And if you want to walk over such a sand spot that is no longer there, then you sink in as if it were a swamp or a moor. "(154)

Then, a few seconds before Crampas' attack on Effi, it says: “She trembled and pushed her fingers tightly together to give herself a hold. Thoughts and images chased each other, and one of these images was the little mother in the poem called 'God's Wall' ”(156). This poem tells “a little story, just very briefly. There was war somewhere, a winter campaign, and an old widow, who was terribly afraid of the enemy, prayed to God that he would build a wall around her to protect her from the enemies of the country. And there God let the house snow in, and the enemy passed it ”(146f.). Salvation there comes about because God literally lets the widow and house sink deep into the snow. So, like most of Fontane's pictures, the sinking is of an ambiguous nature: whether downfall or rescue, or rescue through downfall (as here and at the end of the novel), the respective context decides. The reader already encounters this ambivalence in the first chapter of the novel: “'Flood, flood, make everything good again'” the three girls sing while they “bury their gooseberry bag on the open sea”, and Effi states with satisfaction: “'Hertha, now your guilt is sunk. '"(12)

On the morning after the first love scene with Crampas, the now suspicious Innstetten reports of an (alleged) dream he had that same night: "I dreamed that you had an accident with the sledge in the Schloon, and Crampas was struggling to find you to rescue; I have to call it that, but he sank with you. "(157) It goes without saying that with this vision he intensifies Effi's guilty conscience and her already existing feelings of guilt. But again, rescue beckons through sinking, if only temporarily, because a week after that night the news comes from the Kessiner Hafen that a ship is in distress and is about to sink in front of the pier. Effi and Innstetten rush to the beach and watch how a safety rope is shot over to the castaways and they begin to hoist them ashore with a basket. “Everyone was rescued, and when Effi went home with her husband after half an hour, she would have thrown herself into the dunes and wept. A beautiful feeling had found its place in her heart again, and she was infinitely happy that it was so. "(163)

The creature

Fontane has not only dedicated a large number of images of nature to the "child of nature" (35) Effi to illustrate her naturalness, but has also placed two creatures alongside the Newfoundlander Rollo and the nanny Roswitha, whose creatures are pleasantly different from the affectation of the rest of Kessin society takes off. How much both functionally actually belong together, the author tries to make clear through several parallels.

It starts with the anaphoric consonance of their names, which both sound quite "strange" (108) in the Nordic region of Kessin. It continues with the mediator role that the author repeatedly emphasizes, which both play between Effi and Innstetten, and ends with the protective function and unconditional loyalty that both exercise towards Effi and which does not end even in difficult times: As Effi lives and in modest circumstances Roswitha can only pay scantily, she is still ready to stand by her and stay with her. After Effi died and Rollo refused to eat and lay on her tombstone every day, there is an almost literal parallel to this behavior (even if the intention is contradictory) to Roswitha: when she wants to explain why she after the death of her former mistress who was “quarrelsome and stingy”, didn't just “want to sit in the cemetery and wait until she drops over dead”, she says: “then people would still think that I loved the old woman as much as a loyal dog and would have would not have wanted to leave her grave and would have died. "(106) Significantly, it is Roswitha who instinctively, as it were, first notices that Effi is coming to an end -" I don't know, I feel as if it could be over at any hour “(284) - and it is significant that it is Rollo who remains loyal to her even after death. So the old Briest finds his old assumption (“sometimes it seems to me as if the creature is better than man”, 116) finally confirmed: “Yes, Luise, the creature. That's what I always say. It is not as much with us as we think it is. We always talk about instinct. In the end it's the best. ”(286) Innstetten's friend had already said something similar about Roswitha when he had read her petition:“ 'Yes,' said Wüllersdorf when he folded the paper again, 'she's over.' "(278)

Like most of Theodor Fontane's motifs, Rollo also has a counterpart that confirms and also underlines its function. When Crampas Effi tells the jealous story of the Spanish Bluebeard King Pedro the Cruel and the beautiful "Kalatrava Knight", "whom the queen naturally loved secretly" (135) and whom the king promptly and secretly beheaded in revenge, Crampas also mentions his "beautiful Dog, a Newfoundland dog, ”compares him with Rollo, even baptizing him with the same name for his story. He appeared like a loyal patron saint and vengeance angel of his master after his secret murder at the festive banquet that Pedro supposedly gave in honor of the Kalatrava knight: “And think, my most gracious lady,” Crampas told Effi, “how the king, this Pedro, is about to get up to express his regret that his dear guest is still missing, you hear a scream from the horrified servants outside on the stairs, and before anyone knows what has happened something is chasing along the long banquet table, and now it jumps up on the chair and places a severed head in the empty space, and over this very head Rollo stares at its opposite, the king. Rollo had accompanied his master on his last walk and at the same moment as the ax fell, the faithful animal had grabbed its falling head, and there he was, our friend Rollo, at the long banquet table and sued the royal murderer. "( 136)

The fact that Crampas unconsciously threatens to convert the real blind for Effi from a guardian angel to a ghost figure with the gruesome story of "his blind" brings him unintentionally close to Innstetten, who uses spook as a "calculus of fear" (129) and Crampas' educational means to distance himself and to free Effi. Effi had "become very still" during that story, before she turned back to "her blind": "Come on, Rollo! Poor beast, I can't look at you anymore without thinking of the Kalatrava knight whom the queen secretly loved ”(136). So her constant companion Rollo, the symbol of loyalty, must paradoxically appear to her at the same time as a reminder of her own infidelity.

Figure overview

Literary environment

Effi Briest belongs to the long series of Fontane's social novels, which owe their literary peculiarity to the light tone of the story and the renunciation of accusation or blame while at the same time taking a keen eye on the social and historical situation. If Innstetten kills the seducer Crampas in a duel, which is only a meaningless ritual, and disregards his wife because of the liaison of "riding on principles" (236), which is meaningless even for him, one must not see a unilateral condemnation of the Prussian noble or society . How differentiated the author assesses this question can be seen, among other things, in Innstetten's conversation with his friend Wüllersdorf. Effi forgives her husband, and her mother suspects that she was "perhaps too young" (287) at the marriage that she forced and sponsored. This creates a complex picture of life and morals in the declining old Prussian society. Fontane's work can also be viewed independently of Prussian circumstances as a more general view of the conflict between the individual and social coercion. All of this is revealed in the characters' chats and an almost casual narrative tone in which it is important to read between the lines, because Fontane admitted that what matters to him is not the “what” but the “how”.

However, that doesn't mean that the narrator approves of everything his characters do. The concept of honor of the time, for example, which is expressed in the literary motif of senseless and illegal duels , is repeatedly taken up in various varieties in Fontane's work. With the duel motif, Fontane finds himself in the company of Arthur Schnitzler , who satirically intensifies the meaninglessness of the concept of honor in Lieutenant Gustl (1900), while for the young officer Zosima in Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov (1879-80) the duel was almost the turning point of his life becomes: He refrains from shooting and becomes a pious hermit.

From a literary point of view, Fontane's Effi Briest also stands in the special tradition of the love or seduction novel , comparable to Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert or Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy . The name "Effi Briest" is an allusion to the name of the protagonist Euphemia "Effie" Deans in Walter Scott's 1818 novel The Heart of Midlothian .

Processing of reality in the novel

In his novel Effi Briest, Theodor Fontane was inspired by historical events and the impression that various locations had left on him. Following his idea of a realistic spelling, he used his templates artistically and changed essential details, but the respective template remains recognizable.

Effi Briest

Effi Briest and Elisabeth von Plotho

However, an authentic incident from 1886 actually inspired Theodor Fontane to write his novel: “Elisabeth von Plotho, a young woman from the old Magdeburg-Brandenburg aristocracy, married Armand Léon Baron von Ardenne (1848–1919) despite her reluctance to obey her parents in 1873 ). A few years later, he tolerated the royal magistrate and reserve officer Emil Hartwich from Düsseldorf painting Elisabeth and being with her again and again on this occasion. After Baron von Ardenne had been transferred to the Reich Ministry of War and had therefore moved to Berlin with his family, he observed that his wife corresponded with Hartwich. Having grown suspicious, on the night of November 25th, 1886, he opened the box in which she kept the letters she had received: No doubt, Emil Hartwich and Elisabeth von Ardenne had a relationship! The magistrate whom he telegraphed to Berlin confessed and accepted the baron's request for a pistol duel. It took place on November 27, 1886 on the Hasenheide near Berlin. Emil Hartwich died four days later in the Charité. Baron von Ardenne was arrested but was released after only eighteen days of imprisonment. His marriage was divorced on March 17, 1887, and he received custody of the two children. Unlike Effi Briest in Theodor Fontane's novel, Elisabeth von Ardenne did not give up, but worked as a nurse for years. ”She died in 1952 at the age of 98.

A connection between Effi Briest's fate and the life of Elisabeth von Plotho is therefore evident. Fontane changed many details, however, not only to protect the privacy of those involved, but also to dramatically enhance the effect: Elisabeth von Plotho did not marry her husband when she was 17, but only when he was 19, and he was only five and not 21 years older than her. In addition, they had their relationship not after one, but after twelve years of marriage, and her husband shot the lover not much later, but when the relationship was still going on. After the divorce, as Fontane also knew, the woman by no means withdrew from life, but went into employment.

The way in which the real person Elisabeth von Plotho transformed into the fictional character Effi Briest was analyzed in more detail in two lectures given on September 26, 2006 in front of the Evangelical Academy in Bad Boll .

Effi Briest as a member of the real von Briest family

In the eighth chapter of the novel, Effi states in a conversation with Gieshübler that she is descended from the Briest "who carried out the attack on Rathenow the day before the battle of Fehrbellin ". This is the district administrator Jakob Friedrich von Briest (1631–1703), who acquired the Nennhausen estate for the von Briest family and is said to have been jointly responsible for Brandenburg's victory in the war against Sweden . With this, Effi points out the special part of her family in the rise of Brandenburg / Prussia to a major European power.

Jakob Friedrich von Briest was the great-great-grandfather of Caroline de la Motte Fouqué , born von Briest. In a way, this Briest represents a counter-figure to Effi Briest: she was also the only child of her parents and was unhappily married, but after her marriage failed she was able to marry the second time, namely the divorced aristocrat Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué . Caroline did not become an object of social ostracism and inherited Nennhausen Castle .

Michael Schmidt interprets the use of the name of the real von Briest family as follows: “The secret of the name allusion 'Briest' […] is likely to lie in the discrepancy between the self-confidence of the namesake [Caroline von Briest] and the helplessness of the heroine [Effi Briest]. This discrepancy could be described historically as the difference between a premodern and an early modern, mostly aristocratic proto-emancipation and the dilemma of bourgeois women's emancipation in the 19th century. "

Geert von Innstetten

The modern Geert von Innstetten, who is strangely portrayed without origin and whose relatives are never mentioned, bears a name that never existed as a noble name.

His name could be an echo of an encounter between Theodor Fontane and the Lords of Innhausen and Knyphausen , whom Theodor Fontane met in July 1880 at their manor, Lütetsburg Castle in East Frisia .

It is more likely that the name “Innstetten” can be derived from the name “de la Motte Fouqué”: The French term “la motte” denotes an early medieval castle wall around a residential tower and can therefore be translated as “Ringstätte”. In the fairy tale Undine by the romantic poet de la Motte Fouqué, the water spirit Undine meets a knight of Ringstetten and marries him. According to some performers, Undine corresponds to Caroline and Effi Briest, as well as Ringstetten de la Motte Fouqué and Innstetten. In contrast to the name “Briest”, the name “Innstetten” could only be derived from literature.

Locations

Hohen-Cremmen

The municipality of Elbe-Parey claims that Zerbe Castle was the model for Hohen-Cremmen, as Elisabeth von Plotho grew up there. "Effi tours" organized by the municipality lead there. As a template for the High-Cremmen identified Bernd W. Seiler of the University of Bielefeld but Nennhausen in Brandenburg, the ancestral home of the real family of Briest, between Rathenow , Friesack and Nauen is located. Caroline de la Motte Fouqué died there as the last female family member to be born as a Briest.

The statement made in the first sentence of the novel that the family moved into the manor at the time of Elector Georg Wilhelm von Brandenburg does not apply to either of the two castles in question .

Kessin

Swinoujscie is the model for the Pomeranian district town of Kessin .

Fontane presumably deliberately named both scenes after places that actually exist (namely Kremmen and Kessin ), albeit in a different place than the respective novel locations, in order to prevent his readers from searching too eagerly for parallels between the novel and reality.

Berlin

The impressions of Berlin are based on Theodor Fontane's own biographical impressions. The panorama of the storm on St. Privat , painted by Emil Hünten , was one of his favorite places; Effi and Innstetten meet with Dagobert to visit it.

Stage versions

Effi Briest was of Rainer Behrend fashioned for the play and was dated 9 February 2009 ( premiere ) by 26 June 2013 the Schedule of vagrants stage in Berlin . Another stage adaptation by Peter Hailer and Bernd Schmidt was premiered on May 28, 2011 in the Darmstadt State Theater .

Film adaptations

The step from the path , Germany 1939, 97 minutes

- Director: Gustaf Gründgens

- Actors: Marianne Hoppe (Effi), Karl Ludwig Diehl (Innstetten), Paul Hartmann (Crampas), Paul Bildt (Briest), Käthe Haack (Mrs von Briest), Max Gülstorff (Gieshübler), Hans Leibelt (Wüllersdorf), Elisabeth Flickenschildt ( Tripelli), Renée Stobrawa (Roswitha)

Rosen im Herbst , FRG 1955, 103 minutes

- Director: Rudolf Jugert

- Actors: Ruth Leuwerik (Effi), Bernhard Wicki (Innstetten), Carl Raddatz (Crampas), Paul Hartmann (Briest), Lil Dagover (Frau von Briest), Günther Lüders (Gieshübler), Hans Cossy (Wüllersdorf), Lola Müthel (Tripelli ), Lotte Brackebusch (Roswitha), Margot Trooger (Johanna)

Effi Briest , GDR 1970, 120 minutes

- Director: Wolfgang Luderer

- Actors: Angelica Domröse (Effi), Horst Schulze (Innstetten), Dietrich Körner (Crampas), Gerhard Bienert (Briest), Inge Keller (Frau von Briest), Walter Lendrich (Gieshübler), Adolf Peter Hoffmann (Wüllersdorf), Marianne Wünscher ( Tripelli), Lissy Tempelhof (Roswitha), Krista Siegrid Lau (Johanna), Lisa Macheiner (Minister)

Fontane Effi Briest , FRG 1974, 140 minutes

- Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

- Actors: Hanna Schygulla (Effi), Wolfgang Schenck (Innstetten), Ulli Lommel (Crampas), Herbert Steinmetz (Briest), Lilo Pempeit (Frau von Briest), Hark Bohm (Gieshübler), Karlheinz Böhm (Wüllersdorf), Barbara Valentin (Tripelli ), Ursula Strätz (Roswitha), Irm Hermann (Johanna)

Effi Briest , Germany 2009, 117 minutes

- Directed by Hermine Huntgeburth

- Actors: Julia Jentsch (Effi), Sebastian Koch (Innstetten), Mišel Matičević (Crampas), Juliane Köhler (Briest's wife), Thomas Thieme (Briest), Barbara Auer (Johanna), Margarita Broich (Roswitha), Rüdiger Vogler (Gieshübler )

Radio plays

- 1949: Effi Briest - Production: BR ; Editing: Gerda Corbett ; Composition: Bernhard Eichhorn ; Director: Heinz-Günter Stamm ;

First broadcast: October 5, 1949 | 85'06 minutes

- Speaker:

- Christiane Felsmann : Effi

- Albert Bassermann : Father

- Else Bassermann : mother

- Ernst Schlott : Baron Instetten

- Wolfgang Lukschy : Major von Crampas

- Hans Leibelt : from Wüllersdorf

- Pamela Wedekind : Johanna

- Else Wolz : Cook Roswitha

Publication: CD edition: Der Audio Verlag 2019 (in the collection "Theodor Fontane - The great radio play edition")

- 1974: Effi Briest (3 parts) - Production: SFB / BR / HR ; Editing and direction: Rudolf Noelte ;

First broadcast (part 1): December 14, 1974 | 83'59 minutes First broadcast (part 2): December 15, 1974 | 87'00 minutes first broadcast (part 3): December 17, 1974 | 135'00 minutes

- Speaker:

- Cordula Trantow : Effi Briest

- Martin Held : Father Briest

- Gefion Helmke : Mother Briest

- Friedrich Siemers : Innstetten

- Günther Lüders : Gieshüber

- Harald Leipnitz : Crampas

- Anneliese Römer : Tripelli

- Evelyn Meyka : Johanna

- Paul Edwin Roth : The Speaker

- uva

Publication: CD edition: Der Hörverlag 2008

DVD publications

- Effi Briest. TV feature film based on the novel of the same name by Theodor Fontane. GDR 1968–1970, DEFA 125 minutes, color, director: Wolfgang Luderer. DVDplus (with materials in classic computer formats). Matthias Film Stuttgart (approx. 2011)

literature

Text output

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. Novel. [Preprint] In: Deutsche Rundschau. Volume 81, October to December 1894, pp. 1-32, 161-191, 321-354, Volume 82, January to March 1895, pp. 1-35, 161-196, 321-359.

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. Novel. Fontane, Berlin 1896. ( Digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Theodor Fontane: Selected Works. Novels and short stories in 10 volumes. Volume 8: Effi Briest. Goldmann, Munich 1966.

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. With an afterword by Kurt Wölfel. Reclam, Stuttgart 1969/1991, ISBN 3-15-006961-0 .

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. With materials. Selected and introduced by Hanns-Peter Reisner and Rainer Siegle. Klett, Stuttgart / Düsseldorf / Berlin / Leipzig 1984, ISBN 3-12-351810-8 .

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. Novel. Edited by Christine Hehle. Berlin 1998 (Great Brandenburger Edition, Das narrisches Werk, Vol. 15), ISBN 3-351-03127-0 .

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. Text, commentary and materials. Edited by Helmut Nobis. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-637-00591-4 . (Oldenbourg text editions for students and teachers).

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. With an afterword by Julia Franck . Ullstein, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-548-26979-5 .

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. Reclam XL. Text and comment. Edited by Wolf Dieter Hellberg. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2017.

Secondary literature

- Josef Peter Stern: Effi Briest - Madame Bovary - Anna Karenina . In: Modern Language Review 52 (1957), pp. 363-375.

- Peter Demetz : Forms of Realism: Theodor Fontane. Critical Investigations. Hanser, Munich 1964.

- Dietrich Weber: "Effi Briest": "Also like a fate". About Fontane's suggestive style. In: Yearbook of the Free German Hochstift NF, 1966, pp. 457–474.

- Richard Brinkmann: Theodor Fontane. About the binding nature of the non-binding. Piper, Munich 1967.

- Ingrid Mittenzwei: Language as a topic. Investigations into Fontane's social novels. Gehlen, Bad Homburg 1970.

- Walter Schafarschik (Ed.): Theodor Fontane. Effi Briest. Explanations and documents. Reclam, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-15-008119-X .

- Cordula Kahrmann: Idyll in a novel: Theodor Fontane. Fink, Munich 1973.

- Carl Liesenhoff: Fontane and the literary life of his time. Bouvier, Bonn 1976.

- Anselm Salzer, Eduard v. Tunk: Theodor Fontane. In: Dies .: Illustrated history of German literature. Volume 4 (From Realism to Naturalism), Naumann & Göbel, Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-625-10421-0 , pp. 227-232.

- Horst Budjuhn : Fontane called her “Effi Briest”: the life of Elisabeth von Ardenne. Ullstein / Quadriga, Berlin 1985.

- Bernd W. Seiler: “Effi, you are lost!” From the questionable charm of Fontane's Effi Briest. In: Discussion Deutsch 19 (1988), pp. 586-605. Online: [1]

- Manfred Franke: Life and novel of Elisabeth von Ardenne, Fontanes "Effi Briest". Droste, Düsseldorf 1994 (DNB: http://d-nb.info/94361838X )

- Elsbeth Hamann: Theodor Fontane, Effi Briest. Interpretation. 4th edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-88602-9 .

- Norbert Berger: hour sheets Fontane "Effi Briest". Klett, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-12-927473-1 .

- Jörg Ulrich Meyer-Bothling: Effi Briest exam training . Klett, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-12-352445-5 .

- Manfred Mitter: Theodor Fontane, Effi Briest, interpretation impulses. Mercury, Rinteln. Text booklet: ISBN 978-3-8120-0849-5 , CD-ROM: ISBN 978-3-8120-2849-3 .

- Michael Masanetz: On the life and death of the king's child. Effi Briest or the family novel as an analytical drama. In: Fontane leaves. 72 (2001), pp. 42-93.

- Heide Rohse: “Poor Effi!” Contradictions of gender identity in Fontane's “Effi Briest”. In this: Invisible tears. Effi Briest - Oblomow - Anton Reiser - Passion Christi. Psychoanalytic literary interpretations on Theodor Fontane, Iwan A. Gontscharow, Karl Philipp Moritz and the New Testament. Königshausen & Neumann , Würzburg 2000, pp. 17–31, ISBN 3-8260-1879-6 .

- Thomas Brand: Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. König's explanations : Text analysis and interpretation, 253. C. Bange Verlag , Hollfeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-8044-1951-3 .

- Petra Lihocky: Reading aid “Effi Briest”. Media combination, subject German, Abitur level. Audio book and booklet, both an interpretation. Voices: Thomas Wedekind, Michelle Tischer, Marcus Michalski . Pons Lektürehilfe , Stuttgart 2011, 5th edition; Booklet 60 pages, dialogical technical discussion on CD 93 min.

- Denise Roth: The literary work explains itself. Theodor Fontane's “Effi Briest” and Gabriele Reuter's “From a good family” deciphered poetologically. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin WVB, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86573-679-6 .

- Clemens Freiherr Raitz von Frentz: The story of the real Effi Briest. In: Deutsches Adelsblatt . 52 (2013), 7, pp. 10-13

- Magdalena Kißling: Effi Briest between the ability to act and powerlessness. Fontane, Fassbinder and Huntgeburth in an intermedia comparison. In: Michael Eggers / Christof Hamann (eds.): Comparative literature and didactics. Aisthesis Verlag, Bielefeld 2018, ISBN 978-3-8498-1164-8 .

See also

Web links

- Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest at Zeno.org .

- Effi Briest in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Figure lexicon for Effi Briest by Anke-Marie Lohmeier in the portal Literaturlexikon online .

- Effi Briest in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Effi Briest teaching project

- Effi Briest as a free audio book at LibriVox

- Effi Briest summary and table of contents

Individual evidence

- ↑ Anselm Salzer, Eduard von Tunk: Theodor Fontane. In: Dies .: Illustrated history of German literature. Volume 4 (From Realism to Naturalism), p. 227 f.

- ^ Gordon A. Craig: Deutsche Geschichte 1866-1945. From the English by Karl Heinz Siber, 2nd edition, Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42106-7 , p. 236.

- ↑ Both of Gieshübler's characteristics, namely taking on the role of “doctor” and caring friend for Effi as well as that of “newspaper editor”, are reminiscent of the author Theodor Fontane himself, who was also a pharmacist and journalist and, according to his own statements, in his novels repeatedly knew how to create a mouthpiece for his own convictions with the help of some, mostly older, wise and philanthropic characters.

- ↑ At the same time, however, due to her youth and immaturity, Effi fails to take the reins in hand and fulfill the role she hoped for as Innstetten's wife. After initial uncertainties, she remains passive towards both the outside world, which expects social interaction and hospitable obligations from her, as well as the inside world, which would require active shaping from her as the woman in the Innstetten house. Instead, in Kessin, Effi accepts her role as a child's wife. As is so often the case with Fontane, in Effi Briest it is monotony and boredom that set the stone of bad luck rolling. For Effi it is clear even before the marriage that avoiding boredom through distraction is one of the indispensable ingredients of a "model marriage" (29): Love comes first, but immediately after that comes [sic] glamor and honor, and then comes distraction - yes distraction, always something new, always something that makes me laugh or cry. What I can't stand is boredom. (30)

- ↑ a b Letter of June 12, 1895 to an "acquaintance", quoted from Walter Schafarschik (Ed.): Theodor Fontane. Effi Briest. Explanations and documents. Reclam, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-15-008119-X , p. 110.

- ↑ The phenomenon is described in more detail by the mineralogist Walter A. Franke. In: Walter A. Franke: What is quicksand? "Quicksand" section

- ↑ Fontane is alluding to the phrase "chatting from the sewing box", a more modern form of the phrase "chatting from school" (= "talking about things that are actually secrets of a certain circle", see Lutz Röhrich: Lexicon of proverbs Redensarten. Herder, Freiburg 1973, p. 898). So he uses an already existing linguistic form that was already in use before Effi Briest , and did not create it first.

- ↑ This coincidence is typically triggered by the fact that the little daughter Annie sustains a bleeding forehead wound while playing, for which a bandage must be found as soon as possible, which is then (un) happily in that closed sewing box: not just a very treacherous one Coincidence (cf. the section “Symbolic Motifs” above), but also proof that her father is right when he sees her originally very similar to her spirited mother (“You are so wild, Annie, that you got from mom. Always like a whirlwind ", 273), and a telling indication of how massively Innstetten later reeducated his daughter to be a quiet and well-behaved doll that only moves in embarrassment and mechanically repeats what has been taught to her ( 265f.).

- ^ Theodor Fontane: Selected works. Novels and short stories in 10 volumes. Volume 8: Effi Briest. Goldmann, Munich 1966, p. 287; but also - partly as “wide”, partly as “too wide a field” - on pages 35, 38 and 40 as well as on page 116, where this saying is quoted twice.

- ↑ Kurt Wölfel: Afterword. To: Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. Reclam, Stuttgart 1991, p. 340.

- ↑ On Fontane's style of omission, see also the work by Dietrich Weber: "Effi Briest": "Also like a fate". About Fontane's suggestive style. In: Yearbook of the Free German Hochstift NF, 1966, pp. 457–474.

- ^ Cordula Kahrmann: Idyll in a novel: Theodor Fontane. Fink, Munich 1973, p. 340.

- ^ Cordula Kahrmann: Idyll in a novel: Theodor Fontane. Fink, Munich 1973, p. 340.

- ↑ Peter Demetz: Forms of Realism: Theodor Fontane. Critical Investigations. Hanser, Munich 1964, p. 215.

- ↑ So Fontane in his letter to Josef Viktor Widmann of November 19, 1895. Quoted from: Theodor Fontane: Effi Briest. With materials. Selected and introduced by Hanns-Peter Reisner and Rainer Siegle. Reclam, Stuttgart 1994, p. 347.

- ↑ However, Innstetten treacherously does not stop at the mere statement that “the whole city consists of such strangers” (p. 43), but rather indicates repeatedly even before arriving in Kessin that “everything is uncertain there” and that one is ahead the Kessin "must provide" (p. 43).

- ↑ Crampas, who knows Innstetten and his predilection for "scary stories" well from the past, expresses this suspicion openly. (P. 129)

- ↑ She flirtatiously accuses her mother: "'It's your fault [...] Why don't you make a lady out of me?'"; Theodor Fontane: Selected Works. Novels and short stories in 10 volumes. Volume 8: Effi Briest. Goldmann, Munich 1966, p. 7

- ↑ “'He Innstetten wants to give me jewelry in Venice. He has no idea that I don't care about jewelry. I prefer to climb and I prefer to swing, and preferably always in the fear that it might tear or break somewhere or that I might fall. It won't cost your head straight away. '"; Theodor Fontane: Selected Works. Novels and short stories in 10 volumes. Volume 8: Effi Briest. Goldmann, Munich 1966, p. 32

- ^ Cordula Kahrmann: Idyll in a novel: Theodor Fontane. Fink, Munich 1973, p. 126.

- ^ Cordula Kahrmann: Idyll in a novel: Theodor Fontane. Fink, Munich 1973, p. 127.

- ↑ This is the 1814 poem "Draus bei Schleswig vor der Pforte" by Clemens Brentano. The poem, which was soon set to music, found its way into Bertelsmann's “Small Mission Harp in Church and Folk Tones for Festive and Extra-Festive Circles”, which has been published by Bertelsmann since 1836 and which was sold over two million times in the 19th century. See Wolf-Rüdiger Wagner: Effi Briest and her desire for a Japanese bed umbrella. A look at the media and communication culture in the second half of the 19th century. Munich: kopaed 2016, p. 128

- ↑ Roswitha herself broached this when she heard from Rollo for the first time: “Rollo; that's strange [...] I also have a strange name [...] my name is Roswitha. "(108).

- ↑ Rollo is initially only Innstetten's animal that loves him. But it will also love Effi (45) and later become "her" dog. And Roswitha will be the one who writes the letter to Innstetten (278) to ask for the outcast Effi to send her the old Rollo as a remedy for fear and loneliness.

- ↑ A function that Innstetten assigns to him from the start: "As long as you have the [blind] around you, you are safe and cannot get anything close to you, neither living nor dead." (45)

- ↑ The similarity of this figure to William Shakespeare's Macbeth cannot be overlooked. As is well known, he had secretly murdered his rival Banquo and hypocritically had a big banquet held for him at the same time, at which Banquo's bloody ghost appeared to him as an unmasking sign.

- ↑ Josef Peter Stern compares the three novels: Effi Briest - Madame Bovary - Anna Karenina . In: Modern Language Review 52 (1957), pp. 363-375.

- ↑ Theodor Fontane: What do we mean by realism? 1853

- ↑ Dieter Wunderlich: Theodor Fontane: Effie Briest. Kelkheim 2002/2009

- ↑ Gotthard Erler: Elisabeth von Ardenne - the real Effi Briest. In: Prussia's women. Writings Brandenburg-Preußen-Museum 4, Wustrau 2009, pp. 22–23 and 56–67

- ↑ Albrecht Esche: The life of Elisabeth of Ardenne. and Phöbe Annabel Häcker: Else becomes Effi. For the poetic realization of a figure. (PDF; 420 kB)

- ↑ Horst M. Schütze: The history of the village of Nennhausen near Rathenow ( Memento from January 14, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Preußenweb: Fehrbellin June 18, 1675 - The attack on Rathenow on June 15, 1675.

- ↑ a b Michael Schmidt: Secrets and Allusions or Caroline and Effi von Briest. Name allusion and proto-emancipation in Theodor Fontane's novel. ( Memento of the original from September 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. University of Tromsø. 2000. Nordlit No. 3

- ^ Theodor Fontane: works, writings and letters. Published by Helmuth Nürnberger. Munich. Hanser 1995. p. 1185

- ↑ Elbe-Parey municipality: effis Zerben between the worlds

- ↑ Bernd W. Seiler: Theodor Fontanes "Effi Briest" - The scenes

- ^ Theodor Fontane, Helmuth Nürnberger, Walter Keitel: works, writings and letters. 1962, p. 1137

- ↑ Nora Hoffmann: Photography, painting and visual perception with Theodor Fontane. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025992-6 , p. 46 f.