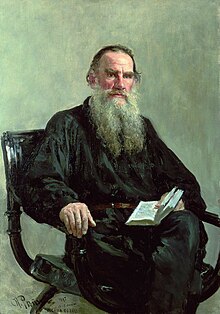

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

Lev Nikolajewitsch Graf Tolstoi ( Russian Лев Николаевич Толсто́й , scientific transliteration Lev Nikolaevič Tolstoj , German often also Leo Tolstoi ; * August 28th July / September 9th 1828 greg. In Yasnaja Poljana near Tula ; † November 7th jul. / 20th November 1910 greg. in Astapovo , Ryazan Governorate , today Leo Tolstoy, Lipetsk Oblast ) was a Russian writer. His main works War and Peace and Anna Karenina are classics of the realistic novel.

Life

Childhood and youth

Lev Tolstoy came from the Russian aristocratic family of the Tolstois . He was the fourth of five children. His father was the Russian Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy (1794–1837), his mother Marija Nikolajewna, née. Princess Volkonskaya (1790-1830). When he was an orphan at the age of nine, his father's sister took over the guardianship. In 1844 he began to study oriental languages at the University of Kazan . After a change to the law school, he interrupted his studies in 1847 off to the location of the 350 inherited serfs in the family estate of the family in Yasnaya Polyana with land reforms to improve (the morning of a landowner). According to other sources, in 1848 he passed the legal candidate exam at the St. Petersburg University “with a narrow need” and then returned to his village.

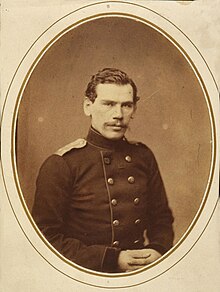

military service

From 1851 on, he experienced the war in the Caucasus in the tsarist army as an ensign in an artillery brigade . His experiences in military operations influenced his early Caucasus stories (The Logging , The Raid , The Cossacks ) . After the outbreak of the Crimean War , he experienced trench warfare in the besieged Sevastopol fortress in 1854 . The realistic reports from this war (1855: Sevastopol tales ) made him known early on as a writer.

Pedagogical reform efforts

From 1855 he lived alternately on the Yasnaya Polyana estate, in Moscow and in Saint Petersburg . From a pedagogical point of view, he traveled to Western European countries in 1857 and 1860/61 and visited artists ( Charles Dickens , Iwan Sergejewitsch Turgenew ) and educators ( Adolph Diesterweg ). After his return he intensified his educational reform efforts and set up village schools based on the Rousseau model . He wrote to a relative (A. A. Tolstaja) living at the court of the Tsar in St. Petersburg:

“When I enter a school and see this crowd of ragged, dirty, emaciated children with their shining eyes […], I feel uneasy and horror, similar to how I felt several times when I saw drowning people. Great God - how can I just pull them out? Who first, who later? [...] I want education for the people only to save the Pushkins drowning there , [...] Lomonosov . And every school is teeming with them. "

He did not primarily strive for selection, but rather an education adapted to the various child personalities. Even after the school was closed by the tsarist administration, Tolstoy continued to pursue the educational goals. He wrote reading books containing narratives on history, physics, biology, and religion to teach children moral and social values. Generations of Russian children received their primary education up to the 1920s with his school book Alphabet, first published in 1872 . The revised new edition from 1875, with a circulation of 1.5 million copies, has been translated into several languages. He had a great influence on the reform movements of free schools like Summerhill .

The great novels

In 1862 Tolstoy married the 18-year-old Sofja Andrejewna Behrs of German descent , with whom he had a total of 13 children. In the following years he wrote the monumental novels War and Peace (1862–1869) and Anna Karenina (1873–1878), which established his literary fame. In his diary in the mid-1850s he noted: "There is something I love more than good: fame."

The time of inner upheaval

With his great recognition a phase of disorientation began for Tolstoy. He felt “at the edge of the abyss”. As a participant in the 1882 census in Moscow, he perceived a misery among the workers that exceeded that of the peasants. Deeply shaken, he tried to counteract the rural exodus by organizing help for farmers affected by bad harvests.

His search for meaning extended to ever wider areas. He gave up smoking, alcohol and hunting ("cruel amusements"). He followed a vegetarian diet and declared that man had to give up meat food if he wanted to develop morally, “because apart from the excitement of passions resulting from this food, it is also quite simply immoral because it involves an act contrary to the feeling of morality - murder - requires, and because it is only required of gourmet food and gluttony ”. His vegetarianism also has a socially critical component: he found it unbearable "that a lot of effort was put into exquisite, refined dishes in the manor house, while all around there was bitter poverty and periodically repeated hunger". "The poverty of the people and the suffering of the animals are terrible," he wrote in his diary in 1857.

Tolstoy repeatedly and often successfully campaigned for politically and religiously persecuted people, visited prisoners for conscientious objection and remained productive as an author, supported by his wife, who alone is said to have copied the 1650 pages of War and Peace seven times. In the story The Canvas Knife, he mocked the human pursuit of possession from the perspective of a horse:

“There are people who call a piece of land 'mine' and have never seen or set foot on this land. In life, people do not seek to do what they think is good, but rather to call as many things as 'mine'. "

Since 1881 he had devoted himself intensively to religious questions. In a series of conversations with leading clergy like the Metropolitan of Moscow and on trips to various churches and monasteries, he developed an aversion to the ritual form of religiosity that he encountered. He juxtaposed this and the practice of faith practiced in western churches, which affirms military service, with the simple teachings of Jesus. To do this, he again translated the Gospels into Russian. As its core, he emphasized charity and the appeal to resist evil without violence.

The dissemination of his views (church and state , what is a Christian allowed and what not?) Drew opposition from political and ecclesiastical institutions.

The time of external conflict

After his respect abroad, he was ostracized at home. Since 1882 he was under police surveillance. My Confession and What My Faith Is In were banned immediately upon publication. It was even rumored that he was mentally deranged . When Tolstoy stressed his responsibility as the author in view of the persecution of his followers, he was answered: “Herr Graf! Your fame is too great for our prisons to house! ”The publication of the novel Resurrection led to the Holy Synod excommunicating him in February 1901 for allegedly -

- deny the Triune God

- deny the risen Son of God Christ from the dead ,

- deny the everlasting virginity of Mary,

- deny the real presence (Tolstoy denied miracles per se and in particular the change ).

Tolstoy showed little remorse. “The teaching of the Church is a theoretically contradictory and harmful lie”, it says in a reply to the Synod, “almost everything is a collection of gross superstition and magic.” But this was “not an unconditional denial, there was always a deep belief behind it of God's work in the world and the effort to fathom the true divine law ”(Brockhaus Encyclopedia).

Tolstoy rejected socialist aspirations in the sense of a dictatorship of the proletariat : “So far the capitalists have ruled, then workers functionaries would rule.” With his moral rigor, he saw himself in a conflict: he threw himself and the rich upper class of which he came egocentric and meaningless way of life. His attitude led him to the question of permanent moral values, which he answered for himself with the claim to unconditional charity and radical non-violence . Against this background, Tolstoy was seen in his later years as a representative of a religiously inspired anarchism ; However, he rejected the ideology of Tolstojanism developed by admirers . His work was considered to pave the way for the revolution of 1905 . His friend Vladimir Stasov wrote to him on September 18, 1906: "Hasn't the entire present Russian revolution shot out of your fire-breathing Vesuvius ?"

Shortly before his death, Mahatma Gandhi , who had already referred to Tolstoy in his youth, had sent him his little book Hind Swaraj ("Indian Self-Government"), a pamphlet against British colonialism in which, according to Tolstoy's principles, he lived a virtuous life without Propagating property in opposition to the capitalist principles of growth and economic progress and explaining its Satyagraha doctrine of nonviolent but active resistance. Tolstoy had read the scriptures and encouraged Gandhi in a letter. Together with supporters, Gandhi founded a settlement in Transvaal (South Africa) in 1910 and named it Tolstoy .

In addition to arbitrary state measures such as the house search in 1908, during which all texts that could be found were confiscated, family conflicts also intensified. Since his wife refused to regard the literary works bequeathed to the Russian people in his will as common property of the people, Tolstoy left the family with his doctor and his youngest daughter on one last, spectacular journey south. On this journey in an open train he fell ill with pneumonia and died in the early morning of November 20, 1910 in the house of the station master of Astapovo (since 1918 Lev Tolstoy, today in Lipetsk Oblast), Ivan Osolin - besieged by the world press. Two days later he was buried in Yasnaya Polyana.

Tolstoy's legacy

After his death, his wife, who had published Tolstoy's works as editor since 1885, published the last complete edition of his works, which she was responsible for. Daughter Alexandra, who was formally appointed by Tolstoy as sole heir of the literary estate, bought the Yasnaya Polyana estate from her mother in 1913. Together with Vladimir Chertkow, she had earned a substantial sum by editing Tolstoy's unpublished writings and selling the rights to a work edition to the publisher Ivan Sytin, thereby fulfilling her father's wish to hand over the lands to the farmers.

When the will became final, Alexandra tried to enforce her property rights to those manuscripts that had been handed over to the archives by the writer's wife with his consent since the late 1880s. Both parties were denied access to the manuscripts pending a decision on this matter. A lengthy dispute in court ensued. This mother-daughter argument was not about copyrights; Tolstaya fully recognized her husband's will. Tolstaja's property rights to the manuscript collection in the archives of the Historical Museum, which were the subject of the dispute, were confirmed by the court and by ukase from the Tsar in 1914 .

Appreciations

Two modern Russian coins were dedicated to Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy in Russia :

- 100 rubles 1991, gold : Tolstoy is sitting in an armchair

- 1 ruble 1988, Cu / Ni: portrait of Tolstoy en face

The flagship of the Russian inland shipping fleet, the Lev Tolstoy , bears his name.

In 1976 the Mercury crater became Tolstoy and in 1984 the asteroid (2810) Lev Tolstoj was named after him. He is also the namesake for the Dolina L'va Tolstogo valley in Antarctica.

Works (selection)

- Childhood (1852)

- The Raid (1853)

- Boyhood (1854)

- The felling (1855)

- Sevastopol (1855/56)

- The Snowstorm (1856)

- A Landlord's Morning (1856)

- Two hussars (1856)

- The demoted (1856)

- Lucerne (1857)

- Adolescence (1857)

- Albert (1858)

- Three Deaths (1859)

- Family happiness (1859)

- Polikushka (1861)

- An Idyll (1862)

- The Cossacks (1863)

- War and Peace (original version) (1867)

- War and Peace (1869) ( online ) (English audio book at LibriVox )

- The Prisoner in the Caucasus (1872)

- Yermak and the conquest of Siberia (1872)

- God sees the truth, but does not say it immediately (1872)

- The Bear Hunt (1875)

- My dogs (1875)

- Anna Karenina (1877) (online)

- Ivan the Fool and His Brothers (1880)

- Critique of Dogmatic Religion (1881)

- What people live on (1881)

- My confession (1882) ( excerpts online as PDF )

- Translation of the Four Gospels (1883)

- What My Faith Is In (1883)

- The canvas knife (1863/1886)

- The Old Two (1885)

- How much earth does man need? (1885)

- Where there is love, there is God (1885)

- Children's wisdom and man's folly (1885)

- Don't let the spark become a flame (1885)

- The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886)

- The Power of Darkness (1886)

- The Candle (1886)

- The three old men (1886)

- Ivan the Fool (1886)

- The egg-sized grain (1886)

- The first brandy burner (1886)

- Ilyas (1886)

- The enemy is tough, but God is strong (1886)

- The Two Brothers and Gold (1886)

- The servant Jemeljan and the empty drum (1886)

- The Baptism Son (1886)

- The repentant sinner (1886)

- Folk Tales (1881–1886)

- Russian farmers (1887) (online)

- About Life (1887)

- The Devil (1889)

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1891)

- The kingdom of heaven within you (1894)

- The Young Tsar's Dream (1894)

- Cruel Amusements (1895)

- Lord and Servant (1895)

- What is art (1898), partial print -from chapter 6-: Against modern art (online)

- Resurrection (1899) (German EA 1900 by Eugen Diederichs in Leipzig in three volumes)

- Father Sergius (1899)

- Patriotism and Government (1900) ( online as PDF )

- What is money (1901)

- About upbringing and education (1902) (online)

- What is religion (1902) (online)

- King Assarhaddon (1903)

- Three questions (1903)

- Notes of a Madman (1903)

- War and Revolution (1904)

- For All Days (1904)

- The counterfeit coupon (1904)

- The Slavery of Our Time (1904)

- The Great Crime (1905)

- Alyosha the Pot (1905)

- The Posthumous Notes of Starets Fyodor Kuzmich (1905)

- Kornej Wasiljew (1905)

- The End of an Age (The Imminent upheaval) (1906)

- For what? (1906)

- The Divine and the Human (1906)

- Power of the Child (1908)

- Songs in the Village (1909)

- The Stranger and the Farmer (1909)

- Who are the killers? (1909)

- The monk priest Iliodorus (1909)

- Grateful Ground (1910)

- All the same (1910)

- Chodynka (1910)

- Three Days in the Country (1910)

- What I saw in a dream (posthumously 1911)

- Father Vasily (posthumously 1911)

- Hajji Murat (posthumously 1912)

- The living corpse (posthumously 1913)

- Legends (posthumously 1925)

- Speech Against War (1983)

- And the light shines in the darkness (drama, unfinished, posthumous, German EA 1912, 1918 Max Reinhardt )

Film adaptations (selection)

- 1917: Father Sergius (Отец Сергий) - Director: Jakow Protasanow

- 1918: The Living Corpse - Director: Richard Oswald

- 1929: The Living Corpse - Directed by Fedor Ozep

- 1930: The White Devil - Director: Alexander Volkov

- 1935: Anna Karenina - directed by Clarence Brown

- 1956: War and Peace - Director: King Vidor

- 1966: War and Peace (Война и мир) - Director: Sergei Bondarchuk

- 1967: Anna Karenina (Анна Каренина) - Director: Alexander Sarchi

- 1969: Scarabea - How much earth do people need? - Director: Hans Jürgen Syberberg

- 1983: The Money (L'Argent based on: The Counterfeit Coupon) - Director: Robert Bresson

- 1996: Captured in the Caucasus (Кавказский пленник) - Director: Sergei Bodrov

- 2001: The Resurrection - Directed by Paolo Taviani , Vittorio Taviani

- 2012: Anna Karenina - Director: Joe Wright

- 2017: Анна Каренина - Director: Karen Shachnasarow

Opera

1903: Siberia , the novel Resurrection served as a template

literature

Primary literature

- Eberhard Dieckmann , Gerhard Dudek (ed.): Lew Tolstoj. Collected works in twenty volumes. Rütten & Loening , Berlin 1964–1978.

- Lev Tolstoj - Sofja Tolstaja: A marriage in letters. Edited and translated from Russian by Ursula Keller and Natalja Sharandak. Insel Verlag , Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-458-17480-6 ( reading sample online as PDF ).

- Lev Tolstoy. War in the Caucasus: The Caucasian Prose. New translation by Rosemarie Tietze . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42836-8 .

Secondary literature

- Rosamund Bartlett: Tolstoy. A Russian life. Profile, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-84668-138-7 .

- Christian Bartolf : Origin of the Doctrine of Non-Resistance. On social ethics and criticism of retaliation in Leo Tolstoy. A contribution to the educational philosophy of modern times. Gandhi Information Center, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-930093-18-9 .

- Pawel Bassinski: Lew Tolstoi - Escape from Paradise Project Publishing , Bochum / Freiburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-89733-260-7 .

- Maximilian Braun : Tolstoj. A literary biography. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 1978, ISBN 3-525-01212-8 .

- Pietro Citati: Leo Tolstoy. A biography. rororo. Bd 13544. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-499-13544-2 .

- Eberhard Dieckmann (ed.): Russian contemporaries about Tolstoy. Reviews, articles, essays 1855–1910. Structure, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-351-01527-5 .

- Martin Doerne : Tolstoj and Dostojewskij. Two Christian utopias. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1969, digitized .

- Anne Edwards: The Tolstoy. War and Peace in a Russian Family. Ullstein book. Bd 27563. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-548-27563-X .

- Wolfgang Eismann: From the end of art ... Tolstoy as theoretician ... ( parts of the article online at Google books ).

- Peter Ernst: Reverence for Life: An attempt to enlighten an enlightened culture. Ethical reason and Christian faith in the work of Albert Schweitzer. With an excursus on religious culture and social ethics in Leo Tolstoy's literary draft. European university publications. Series 23. Vol 414. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-43549-5 .

- Martin George et al. (Ed.): Tolstoj as theological thinker and church critic. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 3-525-56007-9 .

- Horst-Jürgen Gerigk : The Russians in America: Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev and Chekhov in their significance for the literature of the USA. Pressler, Hürtgenwald 1995, ISBN 3-87646-073-5 .

- Horst-Jürgen Gerigk: Tolstoj. A portrait on the 100th anniversary of his death. In: Horst-Jürgen Gerigk: Dichterprofile. Tolstoj, Gottfried Benn, Nabokov. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8253-6117-4 , pp. 15–75.

- Gustav Glogau: Count Leo Tolstoy, a Russian reformer. A contribution to the philosophy of religion. Knowledge Verlag, Schutterwald / Baden 1998, ISBN 3-928640-34-8 .

- Edith Hanke: Prophet of the unfashionable. Leo N. Tolstoj as a cultural critic in the German discussion at the turn of the century. Studies and texts on the social history of literature. Bd 38. Niemeyer , Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-484-35038-5 .

- Klaus Hugler: LN Tolstoy. The strange guest. Regia Verlag 2010, ISBN 978-3-86929-144-4 .

- Ursula Keller , Natalja Sharandak: Lev Tolstoj. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2010, ISBN 978-3-499-50717-5 .

- Geir Kjetsaa: Lev Tolstoy. Poet and religious philosopher. Katz, Gernsbach 2001, ISBN 3-925825-79-7 .

- Ulrich Klemm: Leo Tolstoy - poet, Christian, anarchist. Edition Anares, Hilterfingen, ISBN 978-3-905052-83-1 .

- Janko Lavrin: Lev Tolstoj with self-testimonies and photo documents. 11th edition. Rowohlt's monographs. Volume 57. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-499-50057-4 .

- Wilhelm Lettenbauer: Tolstoj. An introduction. (= Artemis introductions. Volume 11). Artemis, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-7608-1311-9 .

- Thomas Mann : Goethe and Tolstoy. Lecture / essay 1921, read online at archive.org ; ( Walter Kempowski : The best that was said about Tolstoy! in the Zeit-Bibliothek of 100 books)

- Jay Parini: Tolstoy's last year. Translated from the English by Barbara Rojhan-Deyk. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-57034-6 ( partly online at Google books ).

- Alena Petrova: On the understanding of marriage and love in Tolstoy. (in Anna Karenina et al.), PDF file, 39 pp.

- Romain Rolland : The Life of Tolstoy. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1966

- Ludwig Rubiner : Leo Tolstoy. Diary 1895-1899. Max Rascher, Zurich 1918 online - Internet Archive

- Wolfgang Sandfuchs: poet - moralist - anarchist. The German Tolstoy Criticism 1880-1900. M & P, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-476-45137-2 .

- Viktor Schklowski: Leo Tolstoy. A biography. Europe, Vienna 1981, ISBN 3-203-50784-6 .

- Ulrich Schmid: Lev Tolstoy. CH Beck Wissen, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58793-1 , ( foreword online as PDF ).

- Günther Stolzenberg: Tolstoy, Gandhi, Shaw, Schweitzer. Harmony and peace with nature. Echo, Göttingen 1992, ISBN 3-926914-05-X .

- Martin Tamcke: Tolstoy's Religion - A Spiritual Biography. Insel Verlag Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-458-17483-7 , reading sample, 14 pages, PDF file.

- Robert Widl: Light and Darkness in the Life of Lev Tolstoy. Stieglitz, Mühlacker 1994, ISBN 3-7987-0319-1 .

- Magdalene Zurek: Tolstoy's philosophy of art. New forum for general and comparative literary studies, Vol 2., Winter, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-8253-0478-7 .

- Stefan Zweig : Great moments of mankind. Escape to God - An epilogue to Leo Tolstoy's unfinished drama “And the light shines in the darkness” in the Gutenberg-DE Insel Verlag project , Leipzig 1927

- Stefan Zweig : Three poets of their lives. Casanova - Stendhal - Tolstoi in the Gutenberg-DE project The Builders of the World, Volume 3, Insel Verlag , Leipzig 1928

Movies

- Yasnaya Polyana, the Russians and Tolstoy. Documentary, Germany, 75 min., Directors: Christiane Bauermeister, Andreas Christoph Schmidt , production: arte , first broadcast: November 7, 2010, synopsis by ARD .

-

A Russian summer . Feature film, Germany, Russia, United Kingdom, 2009, 112 minutes, director: Michael Hoffman .

The film drama depicts the relationship between Tolstoy and his wife Sofja in his final months. The center is about the struggle of his legacy either for the Russian people or for the Tolstoy family. - Annotated film recordings of Lev Tolstoy 1908–1910 .

Museums / exhibitions

- State LNTolstoy Museum, Moscow

- State Museum and Estate of Leo Tolstoy, Yasnaya Polyana (Tula) (Russian)

- Exhibition (2011): Tolstoy 1828–1910. Museum Strauhof, Zurich (Switzerland), virtual tour

- Leo Nikolajevic Tolstoy - “I cannot be silent!” - Thoughts against violence and war (2008) online exhibition

Web links

- Literature by and about Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Tolstoy at lib.ru (Russian)

- Works by and about Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy at Open Library

- Works by Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Literature by and about Tolstoy on archive.org, here only the German works

- More than 315 publications are listed in the RussGUS database

- Fairy tales by Leo N. Tolstoy near Hekaya: fairy tales, fables and legends from all over the world

- Chronological overview of Tolstoy's life and work

- About Lev Tolstoy

- Eugene Schuyler : Memories of Count Leo Tolstoy in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Isaiah Berlin : The Hedgehog and the Fox - Essay on Tolstoy's understanding of history ; Reading sample PDF

- Christian Bartolf: Tolstoy's Legacy for Mankind. A Manifesto for Nonviolence. (English)

- Insight , magazine of the Pierre Ramus Society , spring 2010: “On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Tolstoy's death, various appreciations and assessments”, online as PDF ( Memento from September 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- Ullrich Hahn, Lecture: Leo Tolstoi - Life against War

- Hanns-Martin Wietek: Lev Nikolaevič Tolstoj, a “human being” | Lev Tolstoj: "The master of all masters, an omniscient Shakespeare ..." | Lev Tolstoj - thinker and philosopher | On the 100th anniversary of the death of Lev Nikolaevič Tolstoj

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Lew Tolstoj. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Alexander Eliasberg : Russian literary history in individual portraits. Leo Tolstoy in the Gutenberg-DE project . Also: Meyer's Large Conversation Lexicon . 6th edition. (1909), Volume 19, p. 599.

- ↑ Leo Tolstoy: The meat eaters / The first stage (final section). Reprinted in: Ending the Slaughter. On the criticism of violence against animals. Heidelberg 2010, text online ( Memento from October 8, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Peter Brang: An Unknown Russia. Cultural history of the vegetarian way of life from the beginning to the present. Cologne 2002, p. 134.

- ↑ Diary entry of August 9, 1857, quoted from Matthias Rude: Antispeziesismus. The liberation of humans and animals in the animal rights movement and the left. Stuttgart 2013, p. 134.

- ↑ Russia News - The Moralist from Yasnaja Polyana

- ↑ Brockhaus Encyclopedia in 24 volumes, 19th edition. FA Brockhaus, Mannheim 1993, ISBN 3-7653-1100-6 , p. 231.

- ↑ See the drama fragment begun around 1895 And the light shines in the darkness .

- ↑ cf. on this Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Sofja Andrejewna Tolstaja. A life by Tolstoy's side. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt / Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-458-17408-0 , p. 13.

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 8801

- ↑ Happy family . Novel. German and with an afterword by Dorothea Trottenberg. Dörlemann Verlag , Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-908777-62-5 .

- ↑ New edition: The empty drum. Fairy tales and legends from ancient Russia. Preface by Wladimir Kaminer ; Diederichs-Verlag 2010, ISBN 978-3-424-35036-4 .

- ^ New edition: Lew Tolstoy (Ed.) For all days - A book of life. Anthology. Preface by Volker Schlöndorff & 7 days of text ( reading sample online as PDF ( memento from 23 September 2015 in the Internet Archive )). Afterword by Ulrich Schmid, also online as PDF ( memento from September 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59367-3 , publisher's website ( Memento from September 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Hajji Murat . Novel. German by Werner Bergengruen and with an afterword by Thomas Grob. Dörlemann Verlag , Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-908777-81-6 .

- ↑ see also Johannes 1,5 EU

- ↑ New production of And the Light Shines in Darkness 2009 by Volker Schlöndorff as a radio play version, first broadcast on the DLF on November 20, 2010.

- ↑ Educational material for the film A Russian Summer , (PDF, 2.7 MB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tolstoy, Lev Nikolayevich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tolstoy, Leo; Tolstoj, Lev Nikolaevič; Лев Николаевич Толстой (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 9, 1828 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Yasnaya Polyana near Tula |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 20, 1910 |

| Place of death | Astapovo |