The Kreutzer Sonata

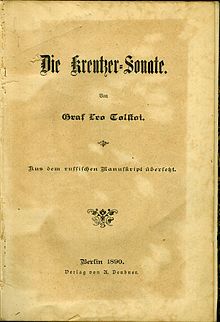

The Kreutzer Sonata (Russian: Крейцерова соната, Kreizerowa sonata) is a novella by Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy , named after Ludwig van Beethoven's popular violin sonata in A major op. 47, which is dedicated to the French violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer . The novella was written in 1887/89. It was first published in 1890 in a German translation, ed. by Raphael Löwenfeld . In Russia the novella was only allowed to appear in 1891.

content

Posdnyshev, his wife's murderer, acquitted for acting out of jealousy, turned gray at an early age, with flashing eyes and nervous demeanor, listens on a long train ride as the travelers discuss love as a basic condition for a happy marriage - a view that especially one does not more young, not particularly attractive, smoking lady is represented. An old merchant, on the other hand, rigorously takes patriarchal, seemingly antiquated views. Finally, after most of them got out, Posdnyschew tells his story: At the age of 30, after years of sexual debauchery, he decides to get married. Although he rejects physical desires as "animal", he is attracted and fascinated by the sensual charms of his bride. In the following years they have five children. His wife - she is now a thirty-year-old beauty - learns that for health reasons she is no longer allowed to have children. The detachment of sensuality from conception is repugnant to the jealous husband. In his perception, giving birth and feeding children was the only insurance against the possible infidelity of his wife. The love life of the Posdnyshevs is now the mere satisfaction of passion; since there is no pregnancy, “the doctors taught them a means to counter this” (Chapter XVIII, first page), and sexual intercourse appears to him to be immoral. Posdnyshev's wife, whose name is not mentioned in the novel, now devotes herself to her personal inclinations, especially the piano. Her husband suspects that she is looking for a new love, and he becomes jealous when she makes music in the house with the violinist Truchachevsky, including Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata . So the marital conflict comes to a head, he kills the alleged adulteress.

Interpretative approach

Tolstoy went two ways with his criticism of Russian society and marriage in particular: First, he let the passengers in a train car discuss Russian society in terms of marriage and love. Some figures advocate the preservation of the "old customs " that women have to subordinate themselves to men and must be aware of this social position. Others vote for equal rights and improved education for women and girls. Especially at the beginning of the story, the main character Posdnyschew wanders from the actual description of his development and his married life to treatise-like monologues about the decline of morals, the "enslavement of women" ( Posdnyschew at least speaks of his wife's body , which he could be entitled to as property) in marriage and the departure from Christian values. As the narrative progresses, Posdnyshev becomes more and more captivated by his description of his own marriage to a woman he does not love and has only married because of a temporary infatuation, revealing that his jealousy, apparently the reason for the failure of the marriage and the murder, is just a delusional imagination. Posdnyschew sees himself as corrupted by society to such an extent that a happy marriage, free from sexual debauchery, in mutual incomprehension, is not possible in the Russian society of that time.

With this novella , Tolstoy has created a profound psychogram of a broken marriage. The main character has learned to observe their actions and to be aware of every act, no matter how small. In addition, the ethical dimension of adultery is woven into it. This leads to further questions:

- Do spouses belong to each other unconditionally?

- Can sexuality only serve to produce children? (results from Chapter XIII)

- To what extent has the (alleged) adulterer Truchachevsky committed moral misconduct?

Ultimately, the questions remain unanswered. The theory of the mutually owned spouse is almost immediately called into question, because Posdnyshev realizes that he has no power over the body of his wife (XXV). The Christian problem of listless childbearing is also not clearly resolved; the problem appears in Chapter XIII and is presented as "monkey activity", which is declared as love. Tolstoy's “ foreword ” is Matth. 5.28 listed; Basically: "... whoever looks at a woman lustfully has already committed marriage." The intention would be the decisive moment. This view is shared by many theologians and philosophers . For a more precise assessment it would be important to ask whether Truchachevsky consented to the intention of adultery. However, this remains a bit hazy. If he had not consented, he would not have acted morally wrong, according to Peter Abelard (scito te ipsum § 8). For Abelard it is crucial whether the person consents to the evil act or whether it remains a mere desire.

epilogue

Tolstoy completed the Kreutzer Sonata on August 26, 1889, ten years later, on April 24, 1900, he wrote an afterword in response to the many letters in which he comments on what I actually think about the subject, the core of the I think of the story published under the title "Die Kreutzersonata".

What went down in world literature as a vividly described marriage drama and subtle psychological study has now become a puritanical guide for young people through Tolstoy's declaration. At first it might seem as if Tolstoy wanted to express an extreme position with the figure of Posdnyshev, the psychogram of a pathologically jealous, emotionally unstable person who describes marital disputes meticulously, but despite his intelligence the vicious circle of word, contradiction and hatred is unable to break through, of a person who has fundamental disorders in his relationship to sexuality and who, in a delusional state, makes extreme generalizations about the excesses of people, the animalism of sex, the double standards of men who are libertines for him, the morally neglected state of society, the role and emancipation of women (which remains only a farce as long as the man regards the woman as the object of his physical pleasure and the woman behaves accordingly) and preaches virginity and sexual abstinence as the solution to everything. The extensive afterword shows us that Tolstoy meant it largely seriously and that he used Posdnyschew as an admittedly high-pitched mouthpiece for his own moral, sexual hygienic and religious convictions. Single people should strive for a natural lifestyle in every respect, that is, they must not drink, eat excessively, enjoy meat, avoid strenuous physical work - which cannot be replaced by gymnastics - and avoid intercourse In their thoughts, they are as little to allow intercourse with strangers as they are with their own mothers, sisters, female relatives or the wives of their friends.

Sofja Tolstaya

In public the woman was equated with Tolstoy's wife Sofja . Although she was deeply humiliated by the description, she campaigned for the work at the censorship authority - in the vain hope that publication would resolve the rumors that had already been circulating through copies of the manuscript. She wrote an alternative: “Whose fault? A woman's story. (On the occasion of Lew Tolstoy's “Kreutzer Sonata”. Written down by Leo Tolstoy's wife in the years 1892/1893) “ , but it was never published. Your counter-novel to the “Kreutzer Sonata” was published in Russia a hundred years late and was translated into German in 2008 under the title “ A Question of Guilt ” .

Return of the topic

The story of Tolstoy and the figure of the violinist are based on Ludwig van Beethoven's Violin Sonata No. 9 , which he dedicated to a violinist who was known at the time (not originally Kreutzer). Based on the Tolstoy story, Leoš Janáček wrote his eponymous string quartet in 1923, from which the love story of the same name by Margriet de Moor was inspired in 2001 (German 2002) , which was filmed several times, most recently in 2007.

reception

- In 1941, Sándor Márai had his protagonists criticize the Kreutzer Sonata in The Changes in a Marriage .

- Kreutzersonata (1937) : Film by Veit Harlan and Eva Leidmann (screenplay) with Lil Dagover , Peter Petersen , Albrecht Schoenhals , Hilde Körber , Walter Werner and Wolfgang Kieling

- Éric Rohmer filmed the story in 1956 under the title "Sonate à Kreutzer". He also played the main role himself.

- In his book Madness in the Family, published in 1988, William Saroyan wrote a story called "The Inscribed Copy of the Kreutzer Sonata"

expenditure

- The Kreutzer Sonata . Translated from the Russian manuscript. Verlag von A. Deubner, Berlin 1890 (The translation differs in many places from other, more recent translations. The translator is not named in this edition.)

- The Kreutzer Sonata . Transferred by August Scholz . Academic publishing house Sebastian Löwenbruck, 1922

- The Kreutzer Sonata . Transferred from Arthur Luther . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1925 - Insel-Bücherei 375

- The Kreutzer Sonata / The Cossacks . Translated from the Russian by Hermann Roskoschny . Schreitersche Verlagbuchhandlung, Berlin undated (approx. 1948)

- The Kreutzer Sonata . German adaptation by H. Lorenz, illustrations by Karl Bauer. Eduard Kaiser Verlag, Klagenfurt undated (approx. 1960)

- The Kreutzer Sonata . Narrative. Translated from the Russian by Arthur Luther, with illustrations by Hugo Steiner-Prag . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1991 (current: 2008 ISBN 3-458-32463-1 [also contains the afterword])

- The Kreutzer Sonata . From the Russian by Raphael Löwenfeld, with an afterword. Anaconda Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-938484-72-1

- as pdf with afterword ( memento of October 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

See also

literature

- Sofja Tolstaja, A question of guilt , Zurich: Manesse-Verl. 2008, ISBN 978-3-7175-2150-1

Film adaptations

- 1914 - Kreitserova sonata - Director: Vladimir Gardin

- Kreitserova sonata (1914) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- 1915 - Kreutzer Sonata - Director: Herbert Brenon

- Kreutzer Sonata (1915) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- 1922 - Die Kreutzersonata - Director: Rolf Petersen

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1922) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- 1936/37 - The Kreutzer Sonata - Director: Veit Harlan

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1937) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- 1956 - The Kreutzer Sonata (La Sonate à Kreutzer) - Director: Éric Rohmer

- La sonate à Kreutzer (1956) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- 1987 - The Kreutzer Sonata (Krejzerowa sonata) - directed by Michail Schweizer

- Kreytserova sonata (1987) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- 2007 - Die Kreutzer Sonata - Director: Bernard Rose

- The Kreutzer Sonata (2008) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Web links

- Detailed article in the literary magazine sandammeer.at

- Vladimir Jakowlewitsch Linkow: Commentary on the text at RVB.ru (Russian)

Individual evidence

- ^ Sándor Márai: Changes in a marriage . Translation Christina Viragh . Piper, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-492-04485-9 , pp. 236-239

- ↑ The Kreutzer Sonata in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Russian В. Я. Линков