war and peace

War and Peace ( Russian Война и миръ (original spelling), German transcription Voina i mir , transliteration Vojna i mir , pronunciation [ vʌj.'na ɪ.'mir ]) is a realistic written style historical novel of the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy . It is considered one of the most important works in world literature and has been filmed several times. In its mixture of historical novels and military-political depictions as well as analyzes of the tsarist feudal society during the Napoleonic era at the beginning of the 19th century in Russia and the wars between 1805 and 1812 with the invasion of Russia in 1812 , it anticipates the assembly technique of modern novels of the 20th century . A draft was completed in 1863 and the first part of it was serially published two years later in the journal Russkiy Vestnik under the title 1805 . Further parts followed until 1867. From 1866 to 1869 Tolstoy rewrote the novel and changed the ending, among other things. This version was published in 1868/69 under the title War and Peace in Moscow.

On the content and meaning of the novel

The novel became world-famous because it depicts the period from 1805 to 1812 from a Russian point of view in an impressive unity, as if under a magnifying glass , in connection with a social and family narrative thread with that of the acts of war, with personal relationship stories and state actions alternating with one another. These actions relate to a philosophical center: the author's view of man and the world. On the one hand, on a large scale, the politically historical overlap in many ways, difficult to understand for the individual - even for the general Napoleon - and causal chains that seem like a network of coincidences. Second, in the personal area, the search for meaning in life and the harmony with oneself. In this context, the author uses the example of the protagonists Andrej and Marja Bolkonski, Natascha and Nikolai Rostow as well as Sonja and v. a. Pierre Visitow in his hike in search of different personality structures and life models in relation to one another. Using them and the contrasting figures of the Kuragin family, he demonstrates his examination of a gutted, alienating life that has been alienated by social structures. The difference between the intellectual Andrei and the emotional man Pierre reflects the division of the Russian elite into Slavophile traditionalists and Western-oriented modernizers. In addition, in contrast to the classical ideal, external beauty does not correlate with spiritual beauty, but the internal light only illuminates the human figure. In this context, the author paints a broad painting of the social city and country life of the Alexander period: atmospherically harmonious family celebrations on name days, house music, tea parties with friends, protections for advancement in the military or government hierarchy, arrangement of relationships in the tension field of sympathies and antipathies, marriage politics with advertisements and rejections, balls as an opportunity for self-expression and networking, representative visits to the theater and opera, symbolic images of the natural atmosphere with sleigh rides and parforce hunts for wolves, customs of the Christmas season, burlesque tavern and street scenes. In many discussions and conversations among the upper classes, passages are written in French, the predominant language of the Russian nobility at the time.

The plot is essentially structured chronologically. In the general descriptions and analyzes of the historical events researched by the author, v. a. the various battles of the Third and Fourth Coalition Wars and the Russian campaign are incorporated into the fictional individual acts in which fictional characters act together with around 120 historical personalities, e. B. Napoleon Bonaparte, Tsar Alexander I or the commander in chief Michail Illarionowitsch Kutuzov . Some protagonists are drawn from real people like the Bolkonskis, who have similarities with the aristocratic Volkonsky family . The narrative form is essentially personal from changing perspectives of the main characters, with authorial comments or explanations about the history, the alliance policy and the military strategies, which apparently reflect the opinion of the author. He often interferes with possessive pronouns in the descriptions of the battles (e.g. our regiment).

Tolstoy has rejected the generic term Roman for his work, because his history painting is a mixture of fictional novel plot, documentaries and discussions of historical, v. a. military strategic representations of the Napoleon period and reflections on their methods and interpretations. Discussions about images of history and people as well as the meaning of life are partly included in the plot, partly there are separate chapters for these analyzes in a general form and an extensive history-philosophical treatise in the 2nd part of the epilogue to conclude the entire work.

Tolstoy's original intention was to write a novel about the Decembrist uprising . In the course of his research on the families of the Decembrists, he concentrated more and more on the Napoleonic Wars, so that the uprising is only hinted at in the epilogue. Tolstoy's own family history, philosophical and historical considerations and historical anecdotes are also incorporated into the work. The novel also indirectly affects social problems, for example the contrasts between nobility and money nobility, between legitimate and illegitimate birth, etc.

According to today's Russian spelling , the word мир in the title can mean both peace and world, society, (national) community . According to the pre-revolutionary orthography, which was valid at the time of the first publication, the two identical- sounding words were spelled differently: міръ for society, миръ for peace . Tolstoy had his work in a first draft with Война и міръ, so the war and society or war and nation overwritten, but this later in миръ ( peace changed). The latter was also used at the time of going to press. Accordingly, Tolstoy himself translated the title as La guerre et la paix into French . Some Slavists, e.g. B. Thomas Grob, but are of the opinion that the older title actually better fits the content of the work.

action

first book

The novel begins in July 1805 in St. Petersburg and Moscow. The country is preparing for war against Napoleon and calls the young men to the army. Her farewell to the families overshadows the soirees and celebrations and contrasts with the detailed description of the luxurious living conditions, the preparation of the balls, the presentation of the cloakroom, the tableware, the menu sequences, the large staff of servants, the courtly, clichéd conversation in French. These conversations are even written in French in the Russian-language original edition in order to show all readers who are not familiar with this language the distance that existed between the majority of Russians and the elite circles. At an evening party in the aristocratic and diplomatic milieu, to which Anna Pavlovna Scherer, a lady-in-waiting and confidante of the empress, has invited, some main characters are introduced. In addition to Anna's acquaintances, there are above all two people who determine the further action: Pierre (Pjotr Kirilowitsch), the illegitimate favorite son of the wealthy Count Visitov, who was raised in France after the death of his mother, was recently brought back to Russia by his terminally ill father. The young man, socialized as a Napoleon supporter in Paris, is a foreign body ridiculed by everyone in the feudal circle with its ritualized manners because of his naive, unconventional directness and social awkwardness. The next day the police sent him away from town because of a night riot after a feast with Anatole Kuragin's friends, and his reckless drinking companion, the officer Fyodor Dolokhov, was demoted (Part I, Chapter VI). In the soiree he meets Prince Andrej Bolkonski, who follows the chats of the guests with disinterest or mockery and therefore appears arrogant, the husband of the “little princess” Lisa (I, IV), who is loved by society for her talkativeness and cheerfulness. Like Pierre, he is bored of the superficial social gossip and the marriage speculation of those present, does not feel happy and is confined in the marriage. He would like to escape from both by participating in the expected war against Napoleon, whom he judged ambivalent, as adjutant to the Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov, and there he would like to find meaning in life and fame in the fight. During this time he brings his pregnant Lisa to Lyssyje Gori, the country residence of the Bolkonskis, to his father Nikolai Andrejewitsch, the so-called "Prussian King" ("The service goes above all"), who lives according to an exact timetable and is feared for his severity and harshness. , I, XXV) and the pious sister Marja (I, XXIII ff.), Who was bound to her father.

With Pierre, the story changes to Moscow to the Families Visitow (I, XII ff.) And Rostov (I, VII ff.), Whereby the events contrast: Count Visitov dies, and since he has no legitimate offspring, some close relatives make up , v. a. Prince Wassili Kuragin and Princess Katharina, hope for the rich legacy. The opening of the will reveals, however, that the inheritance alone was granted to Pierre, together with the title of prince and thus legitimation, by the father. At the same time, the Rostov family cheerfully celebrates the name day of their mother and youngest daughter. Count Ilja Andrejewitsch Rostow and Countess Natalja Rostowa run a generous, hospitable house despite disordered finances, they had to pledge their property and gradually sell it village by village (2nd book, III, XI). In their children, love relationships, marriage wishes and their adaptation to the increasingly narrow financial leeway are discussed: The lively, graceful 13-year-old Natascha (Natalie) and the penniless guard ensign Boris Drubezkoi confess their love, as does the twenty-year-old Nikolai and the one who grew up in the house and fifteen-year-old cousin Sonja, who had no dowry. Vera, the cool eldest, toyed with the idea of a not quite befitting marriage with the son of a poor Livonian country nobleman, the career-conscious officer Alfons Berg. It is the only relationship that is permitted by the parents because of the relatively small dowry of the bride and in the absence of alternatives (2nd book, III, XI). The other children, as well as Boris with his feeling for ascension relationships (2nd book, V, V: Julie Karagin), adapt their ideas over time to the material circumstances and marry rich partners. Only Sonja renounces marriage and remains true to her love. Natascha, who is quickly enthusiastic and likes to be the center of attention, plays a special role in the romance story, with her moods changing depending on the situation.

In the second part , in the first chapters, the author draws a picture of the life of the soldiers in the Upper Austria stage and incorporates the historical events of the Third Coalition War into the novel. In doing so, he allows the reader to meet again some of the people known from the first part: From the perspective of Andrej, Kutuzov's adjutant (II, II ff.), And Nikolais, Junker in the Pavlograd Hussar Regiment (II, IV ff.), One experiences the acts of war . In addition, Dolochow comes as a degraded infantryman in the third company of Captain Timochins (II, I ff.). At the time of the advance of the French troops and the surrender of the Austrian army in front of Ulm, Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov inspects Russian infantry regiments in the Braunau am Inn area, where the coalition's strategy is being discussed. His adjutant Andrej suspects the coming defeat, but sees a probation situation for himself (II, III). The Russian troops withdraw from the outnumbered French and try to hinder their advance by destroying bridges. In such a situation in the hail of bullets on the Enns, Nikolai, in agony, for the first time suspects the dubiousness of his youthful heroic dreams (II, VIII). As the French troops advance further and march into Moravia, the victory of the Allies over a French division at Dürnstein , in which Andrej participates, only means a delay in Napoleon's advance. Andrej accompanies the disorderly retreat of the Russian soldiers, who leave looted villages behind, and joins Bagration's troops , who, with great losses in the battle of Schöngrabern, manage to hold back the numerically superior French vanguard and give Kutuzov's main army time to reorganize. While Andrej tried to convey orders from the commander to the companies on the front line in the hail of bullets and to organize their retreat, Nikolai hoped in Rittmeister Waska Denisov's squadron to experience “the pleasure of an attack about which he had heard so much from his fellow hussars “(II, XIX). However, after his horse is hit and he falls to the ground, he has to flee from the enemy with an injured arm and disaffected on foot, whereas Dolokhov can distinguish himself in combat by capturing a French officer (II, XX).

In the meantime, in the third part in Moscow, Prince Vasili Kuragin has cleverly forced himself to act as a consultant to the inexperienced Pierre, who has been socially courted since his inheritance, helped him to be accepted into the diplomatic corps and the title of chamberlain and not unselfishly took the management out of his hands. He intended him to be his son-in-law and he is staying in his house in Petersburg so that he can meet his beautiful daughter Hélène every day. Their attractiveness excites him, but he knows that this is not love. He feels she is "stupid" because she is not interested in what he is talking about. When thinking about a marriage, he was also bothered by the rumors of a perhaps intimate love story with her brother Anatole: "And again he said to himself that it was impossible for something repulsive, unnatural and, it seemed to him, dishonorable to be in this marriage." , I). But he does not have the strength to leave the Kuragin house. He senses the expectation of the family and the hopeless situation, because he doesn't want to disappoint the hospitable people, but hesitates indecisively about the decision. Finally, the father takes the initiative and simply gives his consent to his alleged advertising and forces Pierre to confess his love. After a month and a half they are married and move into his newly renovated St. Petersburg house (III, II). Kuragin's advertisement for Prince Bolkonsky for his easy-going and wasteful son Anatole is less successful. The unattractive and shy Marja would mean for him the safeguarding of his free, dissolute lifestyle. Bolkonsky saw through the tactics immediately and advised his daughter against a sad marriage (III, III). Marja gets into a conflict situation as a result of the application: She likes the beautiful young man, she dreams of having a family of her own and could end her lonely life in the country, but she suffers from the idea of her old father, who is at the same time in his egocentric love binds to itself and humiliates to be left alone. Her decision is made when, shortly after the advertisement, she surprises her suitor while she is hugging her beautiful French partner Mlle Bourienne, and she rejects the marriage project, disappointed (III, V.).

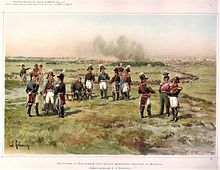

After the Rostov family has finally received Nikolai's reassuring letter after a long period of uncertainty, the plot jumps back to the war zone in Olomouc, where the troops gather for the next battle, the Battle of Austerlitz , and at the parade in front of the Austrian and Russian Emperor parade with euphoric confidence in victory. The narrator is responsible for the defeat between the soldiers and officers fighting at the front, who mostly wander around as if in a fog, disoriented without an overview, and the high command with a large staff at the stage, which argues about its own strategy and about the Napoleons made. In individual cases, the anger at this discrepancy discharges with Nikolai, who was appointed a cornet because of his bravery , when he saw Boris Drubezkoi and Alfons Berg, who have just come from Russia with the guard as in a “walk”, and indirectly also the adjutant Andrej who happened to be present angrily accuses a peaceful war life. This also expresses his criticism of Andrej, who likes to support young men like Boris, although he would refuse this help for himself. Boris, on the other hand, like his mother, uses personal relationships with influential people, who are more decisive than achievements in combat, as a springboard for his career. Nikolái, on the other hand, dreams of fame and heroic death for Russia and the Tsar Alexander whom he adores. Andrej also dreams of fame, to which he would sacrifice everything, but it is the fame of the successful strategist. But nobody listens to an adjutant of Kutuzov, because the Austrian and Russian battle planners ignore the pragmatists in their addiction to profile and complacency and fall for Napoleon's weakness, pretending to be a war ruse, who is wiping out the attacking Russians. Using the example of the two protagonists Andrej and Nikolai, Tolstoy tells of the defeat: once as a single action and secondly in a panorama picture. When Kutuzov's troops flee from the French attacking by surprise and the formations break up, Andrei tries to stop them by grabbing a flag and charging at the enemy, seriously injured in the process, and Napoleon has him taken to the hospital. In the situation of Russian and personal defeat, Andrei becomes aware of the nullity of all greatness, even life and death, "the meaning of which no one among the living could understand and explain" (III, XIX). These thoughts are connected with the situation when he (in the first part, Chapters VIII, IX, of the second book) returned to the country estate of his family Lyssyje Gori cured and witnessed the birth of his son and the death of his wife. On the other hand, Nikolái experiences the full breadth of the downfall. Since Bagration and Dolgorukov have different opinions about the attack, he is supposed to fetch an order from the commander-in-chief for the right wing . During his ride across the entire front he saw the collapse of his own ranks and the panic retreat of the individual units.

second book

Part 1 is about the officers' annual vacation in Moscow before they return to their units. It all begins with the reaction of the nobility to the unexpected defeat at Austerlitz. One blames v. a. the Austrians. Social life with balls, soirees, theatrical performances and the love affairs between the Rostov daughters and visitors are flourishing again. Nikolai, his friend Denisov and other officers are celebrated as heroes. Count Rostov organized a dinner for Commander Bagration in the English Club (I, II ff.). There there is an uproar between Pierre and Dolochow. This was accepted as an old drinking friend in his Petersburg house. Because he was often with his wife Helene and accompanied her to Moscow, the rumor of an affair arose. When Pierre feels provoked by Dolokhov's mocking look during dinner, all his anger comes from the loveless marriage and the dissatisfaction with himself because he has made her a dishonest declaration of love and his cool, majestic wife, who have no children from him want to break out. In his bad mood he challenges Dolochow to a duel for little reason. Contrary to expectations, the clumsy Pierre wins and seriously injures the experienced soldier. The next day he breaks with his wife. Helene denies the allegations and calculates coldly with her husband, whom she considers a fool because of his weakness and whose duel she makes a mockery of Moscow. She immediately agrees to his proposal for a separation, on condition that her standard of living is secure. A week later he gave her the power of disposal over more than half of his property, left and joined a brotherhood of Freemasons in search of the meaning of life (II, I ff.). Helena, on the other hand, continues her lifestyle in Petersburg after her husband's disappearance and at times makes friends with Boris Drubezkoi, who has become a diplomat because of his skillful adaptability and courtly flattery (II, VII). This relationship ends with his renewed interest in Natascha Rostova (III, VII). However, his visits are ended by her mother as not forward-looking for either of them.

Dolokhov is a person with two faces: on the one hand an adventurer and cynic, who impresses the rich young nobles with his antics, sneaks into their families and unscrupulously exploits his effect on women he despises as immoral, on the other hand he loves his old mother and his sick sister, looking for a woman of heavenly purity (I, X). He believes he has found this in Sonja, but she rejects his application out of love for Nikolai (I, XI). In revenge, Dolochow leads his admiring and trusting friend Nikolái to ever higher stakes in the card game, in which he loses a large sum, whereby his father has to go into debt. He recognizes self-critically: "All that, the bad luck, the money, and Dolochow and the resentment and the honor - all of that is nonsense ... but here, the [Natascha's singing when he comes home] is the real thing". (I, XV). So the year 1806 ends sobering for the protagonists: Denisov's applications to Natalie and Dolokhov's to Sonja are rejected, Nikolai's friendship with Dolokhov is broken, as is Pierre's marriage with Helene.

The second part follows the life of the protagonists in the time when Napoleon's army occupied parts of Prussia, continued to advance and was stopped by the Russian army in East Prussia in the battle of Preussisch Eylau (II, IX). After his vacation, Nikolai Rostov returns to his Pavlograd squadron, which is bivouacking poorly at Bartenstein (I, XV ff.). In his attempt to present Tsar Alexander with a pardon for his friend Denisov, he witnessed how the enemy Napoleon became an ally after the peace treaty of Tilsit . Nikolai defends this swing of his adored Tsar as a decision of the sovereign that cannot be criticized: "We do not have to judge ... it must be so" (II, XXI). In the time of peace, with the return of the noble officers, social life in Petersburg revives to its former glory. a. illustrated using the example of a large ball at which the protagonists and their families are brought together (III, XIV ff.)

Pierre and Andrej are completely occupied with their personal problems and are looking for ways out of the crises. On his way to Petersburg, Pierre meets the Freemason Ossip Basdejew, who explains to him, the unfortunate atheist, that one can only absorb the highest wisdom and truth if one purifies and renews oneself inwardly. So far he has lived in idleness and with excesses from the work of his slaves. In solitude, he must begin to contemplate himself, take responsibility and return his wealth to society in order to become satisfied with himself (II, II). Through Basdejew's mediation, Pierre is accepted into the lodge in Peterburg as a “seeker”. He is ready to fight the “evil that reigns in the world” (II, III) and travels to his estates in Kiev Governorate, instructing his administrators to stop the work of the farmers, v. a. of mothers and children, to make it easier to build schools and hospitals and to pursue the goal of liberating them from serfdom and making them free farmers. Before his return to Petersburg, his plans seem to be well on the way, but the philanthropist, who is inexperienced in administration and with his still aristocratic, dissolute lifestyle, does not notice that his chief steward is only showing him a beautiful facade, which he is by shifting workloads has achieved, and that nothing has changed in the structures of government or in the real situation. (II, X). On the way back he visits Andrej, who has taken over the Bogucharowo estate and, with his father, is organizing the drafting of the Landwehr in order to curb his irascible, radical approach. They discuss their controversial human and world views. An idealism based on eternal life and the power of the pantheistic world order contrasts with skepticism about the changeability of conditions. Andrej, disaffected by the campaigns and the death of his wife, distrusts all ideologies of world improvement and no longer wants to actively participate in the war and only care for his son and his family. Nevertheless, Pierre's optimism gives him new hope (II, XI ff.) And In the third part, after five years of seclusion, he returns more mature and relaxed to St. Petersburg society (III; V) to get involved in the reorganization of the state according to the ideas of Montesquieu . He has earned the reputation of a reformer because he has consistently and persistently carried out a social program on his estate that is more pragmatic and more successful than that of the erratic idealist Pierre (III, I). The advisor to Tsar Mikhail Speranski , a strict rationalist, persuaded Andrei to develop proposals for reforming the military laws and the civil code as a member of various commissions (III, VI). However, the unproductive conferences, the idleness of bureaucracy and the neglect of his suggestions disappoint him, and he longs to go back to work on his estate (III, XVIII).

Pierre's development is different. He is still looking, supports social projects, but lives unrestrained undisciplined himself. Many of his St. Petersburg Freemason brothers also do not adhere to the rules of the order. Very few are financially involved in humanitarian tasks, but are more interested in the mysteries or in networking with influential members. When, after a trip to Europe, he made the proposal to help virtuous, enlightened lodge brothers to government offices in order to gain more public influence, a dispute broke out. He is accused of propagating ideas of Illuminati (III, VII). When Basdejew also accuses him of working too little on his self-purification and of refusing reconciliation to his wife, contrary to the commandment of charity and self-perfection, he finally agrees to Helene's return, but does not live with her in marriage. In the meantime she has gained the reputation of a charming, witty lady, in whose salon French and Russian diplomats and high officials frequent. Pierre sees through the hollow operation and plays the absent-minded eccentric and grand seigneur (III, VIII ff.). But inside he is angry with his wife's companions, but tries to control his aggressions and treats himself in the spirit of the Masonic doctrine of self-knowledge and a virtuous life (III, X). After a few years, however, he gives up his attempts at refinement disappointed. He no longer believes in the implementation of the Masonic ideals, in the reshaping of the corrupt human race in order to build a Russian republic, and abandons himself to the elemental force, against which he and the people can do nothing, in the distractions of life: “What he in The attack took place - evil and the lie pushed him back and blocked his way to an activity ”(V, I).

The fourth part focuses on the Rostov family, the endangerment of their lavish lifestyles in the Moscow headquarters and on the Otradnoye estate due to the increasing debt and the provision of their daughters in their marriages with Berg and Andrej Bolkonski. The second connection in particular offers an opportunity for advancement and consolidation. Andrej had the idea of a private new beginning in a second marriage, when 16-year-old Natascha charmed him with her natural, youthful appearance at her first Petersburg Ball (III, XVII). She is also impressed by him and feels flattered in “her favorite state - in love and admiration for herself” (III, XXIII), at the same time she is afraid of the socially respected man. Despite her mixed feelings, she would prefer to get married straight away and is sad about the probationary year agreed with her parents and the right of resignation that only applies to her and not to him. Andrei's skeptical father demanded this deadline as a condition for his consent because of the age difference and the girl's lack of life experience, in the hope that Natasha's love would cool down while his son in Switzerland cured his injuries (III, XXIII). During the engagement period, which is not made public, Natascha lives with her family on Otradnoye. When she takes part in parforce hunts for wolves with Nikolai, who took a leave of absence from his hussar regiment to support his old parents (IV, IV ff.), With the original uncle in the village of Michailowka, as a contrast to the usual feudal style, or gets to know original rural life Visiting the neighbors (IV, X) during the Christmas days, disguised in a nightly mummery, she feels happy and full of vigor, but on the evenly calm winter days, her wedding time becomes very long. “What was going on in this child-like, receptive soul that so eagerly absorbed and appropriated the most diverse impressions of life? How was it all arranged in her? ”Asks the narrator, hinting at the coming events, after the Rostov siblings visited their uncle in his rural idyll (Book 2, IV, VII). The fourth part ends with an argument between Nikolai, who wants to marry Sonja, and his parents, who refuse to give their consent. Without reaching an understanding, he travels back to his regiment.

The fifth part tells the dramatic turn in Natascha's engagement story. This combines two developments. The starting point is Count Rostov's trip to Moscow with Natascha and Sonja to sell his estate, to get Natascha's trousseau and to get to know the groom's family (V, VI). When the stubborn Count Bolkonski and his daughter Marja visit, they feel their rejection (V, VII). This unsettles Natascha and after the long wait she doubts that she will be accepted into Andrej's family. At the same time, to compensate for the humiliation, she enjoys her admiration in St. Petersburg society, and her as yet unsettled personality becomes the victim of an intrigue of the recklessly only use of the moment and irresponsible Anatole Kuragin in this unstable phase of life. He sees the beautiful girl attending the opera, is fascinated by her and would like to have her as a lover (V, VIII ff.). He forges the daring plan to persuade her to flee together, to fake marriage because he has already had to marry a girl he has seduced, and to live with her abroad as long as the borrowed money lasts. His equally unscrupulous sister Helene, from whose splendor Natascha is intoxicated, mediates the meeting of the two (V, XIII) and his drinking friends, u. a. Dolochow, who repeatedly appears as a daredevil, have fun with the adventure (V, XVI). She is flattered by the gallant, passionate advertising of Anatole, who is ready to give up everything for her. She thinks that she has found her great love, ends her engagement with Andrej in a letter to his sister and goes on the run. But the plan is discovered by Sonja and the execution is prevented (V, XVIII). Called for help, Pierre tries to cover up the incident, which was dishonorable for the Rostovs, and he forces his brother-in-law Anatole to leave Moscow (V, XX). Natascha is desperate and, when she learns the background, wants to poison herself. Pierre takes pity on her and offers her his friendly support, noting that he has loved her for a long time and has so far suppressed his love because of her youth (V, XXII and 3rd book, III, XXIX). His care supports their regeneration. V. a. she seeks redemption from her feelings of guilt in faith (Third Book, I, XVI ff.). After her recovery, he withdraws from her psychological crisis so as not to complicate the situation further. After his return, Prince Andrei reacts calmly on the outside, deeply hurt on the inside, to Natascha's refusal. His family is relieved about the outcome (V, XXI).

Third book

From the third book on, the authorial narrator, and thus obviously the author, comes more and more to the fore and deals in detail in individual sections with the historical accounts and their evaluations of the French and Russian war strategies (e.g. for the battle of Borodino in : II, XXIII and XXVII ff.) Apart. The basis is his view of history of the continuum (III, I and II) and of the polycausality, i. H. the many events linked to one another throughout the course, which ultimately predestined, d. H. are predetermined by eternity and not by individual action. “[A] owing to their personal characteristics, habits, requirements and intentions, all the innumerable people who took part in this war acted [...] and yet they were all unwillingly tools of history and performed a work that was hidden from them but understandable to us. This is the unalterable skill of all those practicing, and the higher they are in the human hierarchy, the less free they are ”(II, I). In his opinion the leaders are only figureheads for the soldiers who admire them. The decisive factor is the “spirit of the army”, i. H. the desire to fight and to expose oneself to danger as a "multiplier of the mass" of the soldiers (4th book, III, II). The narrator sees himself confirmed in this opinion by his discussion of the disadvantages of the Napoleonic central strategy over the advantages of the Russian tactics of disintegration and the partisan war when the French army withdraws. The positive example for him is the Russian General Kutuzov. He gave his soldiers a "feeling that was just as in the soul of the commander-in-chief as in the soul of every Russian" (II, XXXV). Because the leaders have no overview and their orders often do not reach the fighters or cannot be carried out because the situation has changed in the meantime. The decisive orders, however, as the experienced Kutuzov knows (II, XXXV), come from the commanders close to the front lines (II, XXXIII). The commander-in-chief also represents this knowledge to the impatient Andrej: “There is no one stronger than the two warriors - patience and time […] I tell you what one has to do and what I am doing. Dans le doute [When in doubt] […] abstiens toi [hold back] ”(II, XVI). So he has to withdraw his troops weakened by the battle of Borodino and forego defending Moscow in order to await a better opportunity (III, IV). Even after the withdrawal of the Napoleonic troops, he avoids a major battle and relies on the exhaustion of the French army on their way through the destroyed and plundered provinces (4th book, II, XIX). This contrasts the old, physically frail, simple Kutuzov with the powerfully acting, majestically glamorous Napoleon, who is accustomed to success and convinced of his strategic genius, who invaded Russia with the armed forces of twelve peoples of Europe (II, XXVI ff. And XXXIII ff.) . Both represent the opposition between Russian heterogeneity and Napoleonic centralism based on the will of a single man. In the battle of Borodino he experiences his borders for the first time (II, XXXIV), but without changing his justification for the war of changing a French Europe for the benefit of the peoples with Paris as the capital of the world (II, XXXVIII), and defies heavy losses continued on Moscow. The skepticism of the narrator about the image of the key role of great leaders in world history corresponds to his version of the causes of the fire in Moscow: no planned action, but the lack of responsibility for the houses abandoned by their owners and the collapsed structures of order (III, XXVI ). In several chapter introductions the narrator repeats in connection with the descriptions - z. B. Pierre's regiment set up to defend the country plunders Russian villages - his conception of the limitations of individual rational action, which can even be counterproductive: “Only unconscious action is fruitful, and he who plays a role in a historical event becomes never understand its meaning. If he nevertheless tries to understand it, he will be struck by how sterile it is ”(4th book, I, IV).

The narrator describes his view of history using the example of the Russian campaign ( part 2 ), with the fictional and historical characters again becoming observers and carriers of the individual transactions, which alternate with the general descriptions: Nikolai and his squadron of horsemen take part and become in the battle of Ostrovno promoted. Andrej decides to no longer take part in the war as an adjutant on the staff, but as the commander of a fiercely fighting regiment. He criticizes the retreat strategy of the Prussian officers as unpatriotic and demoralizing for the Russian soldiers. At his last meeting with Pierre on the evening before the Battle of Borodino, he explains to him why this fight is worth killing him. Wounded by life, he projects his downfall into battle: “[I] I would not take prisoners […] The French have destroyed my house and are on their way to destroy Moscow, they have insulted me […] They are my enemies , are all criminals in my terms ”(II, XXV). Even before he got to the headquarters, he was following the violent, fruitless discussion of eight parties about the best strategy, with theoretical constructs of the Prussian generals, factual arguments, patriotism, personal profiles and career hopes standing in the way of each other (I, IX). This disagreement confirms his atheistic, hopeless worldview (also in the life review in II, XXIV) of war as the “most hideous in life”, which is celebrated by the victor with thanksgiving services: “How can God watch from there and listen to them! [...] I see that I am beginning to understand too much. And it is not good for people to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and bad ... Not much longer! ”(II, XXV). He is already bitter about his unhappy fate, about his misunderstanding of Natascha's sincerity and spiritual openness (II, XXV) and about the strife with which his dictatorial father is burdening his sister and himself when he returned to the war. "[...] when you consider what and who - what nothing can be the cause of all misfortune a person can be!" He said to Marja when she parted. He has been obsessed with the idea of dueling with Anatole, who has upset his family order twice, and hopes to meet him in the army, although he sees no point in that either: “Only senseless apparitions turned up one after the other without any connection others in Prince Andrej's imagination ”(I, VIII). He only sees the unconscious, amputated leg Anatole in the hospital tent, where he is being operated on after a life-threatening injury from a grenade, from which he did not take cover, and he realizes: “Pity, love for the brothers, the lovers, love for those who hate us, love for enemies, yes, the love that God has proclaimed on earth and that Princess Marja taught me and which I did not understand; that is why I was sorry for life, that is what I would have had if I could have continued to live ”(II, XXXVII).

After the old Prince Bolkonski suffered a stroke when he found out about Smolensk's abandonment and the advance of the French, Marja left the Lyssyje Gory estate (II, V) with her paralyzed father and servants and moved to Bogucharovo, where the Prince dies after further attacks (II, VIII). Here they are soon caught between the fronts. Marja herself is helpless and not prepared to take responsibility. In addition, after the last words of his love for her, shortly before his death, she is plagued by feelings of guilt for having wished for his release. The manager advises her to flee to Moscow from the approaching French, but the villagers want to prevent that and do not give her horses. They are dissatisfied, as they have had to bear the burden of war for years, and hope that their situation will improve, as the French have promised them not to destroy their houses and to treat them well. That is why they refuse Marja's offer to leave the village with her and get apartments on another estate. In this situation Nikolai Rostov comes to the village in search of provisions for his squadron, forces the rebellious farmers to give up and organizes Marja's escape. She falls in love with her savior and he thinks about a marriage with the gentle and rich heiress.

The approach of the Napoleonic troops frightens the Moscow nobility and the merchants and puts them in a patriotic intoxication to defend their fatherland against the "enemy of humanity". On the other hand, in the salons of Anna Scherers and Helenes in St. Petersburg, discussions are held at court about the advisers who influenced the Tsar and their competencies (II, VI). In the patriotic mood, the upper class tried to learn to speak Russian and then, also out of fear of the discontented people, went to St. Petersburg to safety.

The former Freemason Pierre is ready to sell an estate in order to finance new troops (I, XXII ff.), But in his indecision remains passive and expects “something horrific with fear and joy at the same time”. Finally, in a sudden need to “sacrifice everything”, without knowing why, he travels to the front: “[I] m sacrificing himself there was a new joyful feeling for him” (II, XVIII), to see the course up close the Battle of Borodino, the fighting and death of the soldiers. From his perspective, the reader follows the change in the war scene: In the morning he naively looks from a hill far over the landscape “and died with delight at the beauty of the spectacle [...] now the whole area was covered by troops and the clouds of smoke from the shots the oblique rays of the shining sun […] cast a piercing, golden and pink-tinted light in the clear morning air ”(II, XXX). After tens of thousands had struggled for the famous “Rajewski battery”, he was horrified to see how between many dead people “multitudes of […] Russian and French wounded men with their faces disfigured by suffering walked, crawled and […] carried on stretchers by the battery [ were] [...] the noise from the gunfire [...] increased to despair, like a person who overexerted himself and screamed with his last strength ”(II, XXXII). He returns to Moscow, confused about his previous disoriented and changeable life in search of self-discovery, helpless and hopeless.

The third part is about the situation after the Battle of Borodino. Many injured people have been brought to Moscow, while on the other hand many residents flee the city for fear of occupation by Napoleonic troops and looting. a. after it became known that Kutuzov had to give up the plan to defend Moscow after consulting with his generals (III, IV and XIX). The patriotic commander Rastoptschin , on the other hand, tried for a long time to keep the population in the city and to call on them to fight. This leads to contradicting instructions and breakdowns during the trigger. The narrator accuses him of calling for lynch justice to one of Napoleon's supporters, who is accused of treason (III, XXV).

The Rostovs leave their house shortly before the Russian army withdraws (III, XIX) and Napoleon leaves an almost deserted, but well-stocked city with food and valuables left behind (III, XX ff.) To Natascha, after overcoming her crisis, again in original vitality , has in the parents' dispute whether their car has the valuable household effects or injuries, etc. a. The fatally wounded Andrei, who was initially not recognized by the family, was supposed to be transported, vehemently supported the compassionate father and thus enforced the humanitarian priority over the material one (III, XVI). When she found out about Andrei in Mytishchi, around 20 km from Moscow, in front of the firelight of the burning city, she asks his forgiveness while he confesses his love for her and helps as a nurse with his care (III, XXXII).

On their way out, the Rostovs met Pierre, who on his return is immediately warned by the governor not to contact any Freemasons suspected of treason. Then he learns of the planned divorce through Helene's letter (III, X). In the meantime, she has privately rescheduled in Petersburg and pitted two of her suitors, an old dignitary from one of the highest state offices and a young foreign prince, against each other, so that both have proposed marriage to her (III, VI ff.). The prerequisite for this is their conversion to the Catholic faith due to the non-recognition of their first marriage. But she dies before her divorce after gynecological treatment. While reading the letter without interest, Pierre finds himself in a state of utter confusion and hides in the house of the late Freemason Ossip Basdejew. Torn between patriotic and universalistic ideas, the feeling "having to be prepared to sacrifice and suffer in the awareness of the general misfortune" (III, XXII), he feels himself once in a "thought construction of vengeance, murder and self-sacrifice" (III; XXIX) called to assassinate Napoleon, on the other hand he saves the life of the French captain Ramball when he is billeted in the house from the attack of the insane Makar Basdejew (III, XXVIII) and after a friendly conversation with the occupant, he senses his old weakness not being able to carry out the project (III, XXIX). The next morning he remembers his plan again. His way leads through streets with burning or robbed houses and looting soldiers. He wants to help, fetches a three-year-old girl who is wanted by her helpless parents who have become homeless from the garden of a burning house, protects an Armenian woman from two marauding soldiers and is arrested by a patrol in the process (III, XXXIV). He is accused of arson and espionage and he falls helplessly into the now prevailing French "order, the coincidence of circumstances", which not only he does not see through, because the chain of order recipients itself has no information (4th book I, X) : Interrogation, prison, 2nd interrogation, place of execution, pardon for prisoners of war and transport with the troops withdrawing from Moscow are the stages of the automatic process.

Fourth book

The narrator changes the scenery at the beginning of the first part and shows the great discrepancy between occupied Moscow and the discussions of the Petersburg society on patriotism and the defense of the fatherland, while their luxury style is not impaired (I, I ff.), Nor does it like the life of the Russians in the provinces not affected by the war. Nikolai can convince himself of this when he is transferred to Voronezh to requisition the army with horses. Here, and thus the personal development and relationship history of the protagonists is pursued further, he meets Marja at her aunt and feels irresistibly attracted by her "spiritual world, which is alien to him in all its depths [...]" (I, VII). At the same time Sonja writes to him about the loss of Rostov's property in Moscow, renounces his promise and gives him the freedom to marry a rich woman out of family interests. However, she decided to make her sacrifice in a situation when Andrei was feeling a little better and she had hope of a renewal of his relationship with Natascha, which would stabilize the Rostov's finances and a marriage between Nikolai and Marja, who was then closely related to him, would not would be necessary (I, VIII).

When Maria learns from Nikolái that her sick brother is being cared for by the Rostovs, she travels to Yaroslavl and can say goodbye to Andrei (I, XIV ff.) When she arrives, after a brief hope of living with Natascha, he is already in a phase of “alienation from everything earthly and a joyful and strange lightness of being. Without hurry or restlessness, he awaited what was to come. This terrifying, eternal, unknown and distant, the presence of which he had constantly felt throughout his life, now it was for him the near and […] the almost understandable and tangible ”(I, XVI). Natascha and Marja become friends (IV, I ff.) Through the common suffering, reinforced by the news of Petya Rostov's death (IV, I ff.) And travel to Moscow (IV, III) after the French leave.

A new low has been reached in Pierre's development. Under the impression of the executions, when he only realized after the end of the executions that he himself only had to watch as a deterrent, and of the murder "committed by people who did not want to do that, the pen suddenly appeared, all of which seem to be held and alive left, torn out of his soul, and everything had collapsed into a heap of senseless rubble [...] the belief in him in a well-ordered world, in the human, in his soul and in God was destroyed ”(I, XII). From this crisis he got acquainted with a fellow prisoner, the common soldier Platon Karatajew, who in the 4th book no longer managed the march to Smolensk and was shot by French soldiers (III, XV). His devotion to his lot ("Fate always seeks a head. And we always want to right: that is not good, that is not right") and his simple piety impress him and "the previously destroyed world [arose] now in new beauty in his soul ”(I, XII). Through this poor life, in four weeks he achieved "that peace and satisfaction with himself, for which he had previously looked in vain [...] harmony with himself". He recognized “that all striving for positive happiness that is inherent in us is there only to torment us without satisfying us. […] The absence of suffering, the satisfaction of needs and, as a result, the freedom to choose one's occupation, that is, one's way of life, now seemed to Pierre to be undoubtedly man's greatest happiness ”. He has seen that excessive comforts in life destroy all happiness through the satisfaction of needs (II, XII).

With the second part , the act of war with general descriptions and analyzes comes to the fore again: the "flank march" of the Russians first to the east and then in a curve to the south in order to deceive the following Napoleonic troops (II, I ff.), The Napoleon's withdrawal from Moscow and the Russian reactions, such as the attack in the Battle of Tarutino (II, III ff.) Or Kutuzov's avoidance of a large-scale, costly dispute and the observation of the enemy, which is increasingly decimating due to supply shortages, accompanied by attacks by small groups. Overall, the narrator sees himself confirmed in his explanation of Davydov's associations operating independently of one another in partisan tactics in his historical picture of creative disorder due to the non-coordinable aspects and the divergence of interests. On the other hand, he investigates the strategy of the alleged genius Napoleon, which he does not understand, and may sit down. a. with its ineffective proclamations and the moral disintegration and the indiscipline of its marauding army, which finally leads to the abandonment of Moscow (II, VIII ff), to the march back, to the increasingly disorderly flight and thus to the extensive destruction of the great army. He defends Kutuzov against criticism in his own country from the accusation of militarily, e.g. B. at the Battle of the Beresina (IV, X) held back from not having captured Napoleon and his staff and thus not having ended his policy of expansion. The narrator incorporates this controversial discussion into fictional individual acts in which the general is shown close to the people and also sympathetically towards the prisoners (IV, VI). Kutuzov's goal, and his military possibility, was not the European dimension of Tsar Alexander, but rather to drive the enemy out of the country without a major battle and to deal responsibly with one's own forces out of his national feeling with a "people's war" (III, XIX and IV , IV ff.). In this context he warns against a glorification of Napoleon and against seeing a sign of greatness in the decision to leave his soldiers behind and save himself with his sleigh ride. He ironically quotes Napoleon: "From the sublime to the ridiculous is only one step" (III, XVIII).

In the individual trades, the new tactics are illustrated in the operations of Denisov with his Cossack troop, which Petya, the youngest son of the Rostovs, has joined (III, III ff.). It is the big time for daredevil fighters like Dolokhov, who in French uniform scouts the positions and operations of the enemy. At one point he is accompanied by the naive war enthusiast Petya, who wants to prove himself as a hero in battle and is impatiently looking forward to his mission. Without listening to Denisov's warnings, he rode stormily in the courtyard of a French-occupied manor house in the hail of bullets that was fatal for him (III, IV ff.). During this action Russian prisoners, u. a. Pierre, exempt (III, XI). On his march with his group, decimated by hunger and disease, past destroyed wagons and animal carcasses, he did not give up his new worldly view of life. He copes day by day and does not think about himself: "The more difficult his situation became, the more terrible the future was, the more independent of the situation in which he found himself, joyful and calming thoughts, memories and ideas came to him" ( III, XII). After his liberation, he returned to Moscow optimistic. The city is being rebuilt after the fire. He regulates the renovation of his houses and the debts of his wife, for whom he now feels pity, as he does for everyone. When he talks to Marja and Natascha about their sad experiences (IV, XV ff.), Everyone realizes that they have changed and matured in life. Pierre and Natascha associate the common grief over the dead of their families with the hope of a new beginning in a marriage. He will later recall this phase as the "time of happy madness". Through Natascha, Pierre's "heart [...] is so overflowing with love that he loved people for no reason and found irrefutable reasons for which it was worth loving them." (IV, XX).

epilogue

The historical considerations of individual chapters of the four books are summarized and systematized in the epilogue in a kind of essay: In the first chapters of the first part, the narrator (or author) takes various historical analyzes v. a. of the 3rd and 4th books. He describes the successes and failures of Napoleon and Tsar Alexander and sees in them their role in the great game of the history director, which is incomprehensible to man. In the second part he examines the question of the force that moves peoples and makes them wage wars. In doing so, he deals with theories and definitions of historians from different centuries and expands the consideration to philosophical questions about the nature of man, his possibilities and limits. Aspects of the analysis are the divine guidance, the alleged ingenuity of politicians and generals or the result of the development from a multitude of differently oriented forces with circular movements, philosophical and political ideas, the free will of the individual and the law of necessity, the will of the masses, political power and unlawful violence. He comes to the conclusion that historical research should look at events as objectively, undogmatic and differentiated as possible.

The private storyline in the first part (I, V ff.) Takes place between 1813 and 1820 and is about the connections between Nataschas and Pierre as well as Marja and Nikolai. While Pierre and Natascha's marriage is concluded after the year of mourning, after the death of his father Nikolai finds it difficult to reconcile the repayment of his family debts by marrying the rich Marja with his honor. With his civil servant salary he can entertain his mother, who has to keep the financial situation a secret, and Sonja. But Marja manages to convince him of a solution on the basis of her love. They get married, live with his family and Andrei's son Nikolai on their Lyssyje Gory estate. He takes care of administration and agriculture and can use the income to pay off the debts. His recipe for success is to observe the work of his farmers and to think through them. In this way he can learn a lot for himself and at the same time gain their trust and cooperate well with them (I, VII). The harmonious family situation is described during the visit of the Rostovs' stay with the Rostovs in autumn and winter of 1820 (I; IX ff.). Marja and Natascha found the fulfillment of life in their roles as happy mothers and wives. Natascha has even given up her vanity and addiction to cleaning and admires her clever husband. Marja keeps a diary about her children and the thoughts about the correct method of upbringing, and Nikolai, who is often dissatisfied with himself because of his lack of self-control, loves her because of her superior soul and her sublime moral world. They live with their numerous children, like the old Rostovs, completely focused on the family, but socially reduced and more modest, in a bourgeois-moral family conception. Because of his calm, friendly personality, Pierre becomes the focus figure during his visits, to whom all sympathies go, v. a. Andrej's son, the sensitive 15-year-old Nikolenka, sees his father's old friend as his role model. Like him, he doesn't want to be a soldier, but a scholar. He listens attentively as Pierre talks about his conversations with like-minded people in Petersburg, to whom he presented the idea of a Russian union of virtues for the moral and social reform of society, while Nikolai fears an uprising against the government, which he would defend as a soldier. Perhaps this is a reference to the Decembrist revolt five years later.

Overview of the main characters

The following table of the main characters in Tolstoy's War and Peace

is arranged in the first column according to the family , so that the persons belonging to a family stand together. The table can be ![]() rearranged by one column at a time by clicking on .

rearranged by one column at a time by clicking on .

In the Relationship / Characteristics column, relationships are shown by referring to family names and numbers in the Family column . So z. B. "Niece of Besúchow 1": niece of Count Kiríll Wladímirowitsch Besúchow, who is classified as Besúchow 1 in the family column .

Except for German name forms, the stress is indicated by an accent (´) above the stressed vowel.

The endings -owitsch / -ewitsch, -itsch and -ytsch are synonymous with the patronymic, e.g. B. Ivánowitsch, Ivánitsch, Iványtsch.

| → Column sorting |

| family | title | First name | Patronymic | family name | Nickname | Relationship / characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagratión | Prince | Pyotr | Ivanovich | Bagratión | Army commander | |

| Balashev | Balashev | Adjutant General of the Tsar | ||||

| Mountain 1 | Alfons | Karlych | mountain | Adolf | Officer of German origin | |

| Mountain 2 | Vera | Ilyinichna | Berg, b. Rostówa | Mrs. von Berg 1, oldest daughter from Rostów 1 | ||

| Besúchow 1 | Count | Kiríll | Vladímirovich | Besuchow | ||

| Besúchow 2 | Count | Peter, Pjotr | Kirillowich | Besuchow | Pierre | illegitimate son of Besúchow 1 |

| Besúchow 3 | countess | Helene | Vasilievna | Besúchowa born Kurágina | Lola | 1. Mrs. von Besúchow 2 |

| Besúchow 4 | countess | Natalie | Ilyinichna | Besúchowa born Rostówa | Natascha | 2. Mrs. von Besúchow 2 |

| Besúchow 5 | princess | Catherine | Semjonowna | Mamontova | Catíche | Niece of Besúchow 1 |

| Besúchow 6 | princess | Olga | Mamontova | Niece of Besúchow 1 | ||

| Besúchow 7 | princess | Sophie | Mamontova | Niece of Besúchow 1 | ||

| Besúchow 8 | Ósip, Òssip | Alexéjewitsch | Basdjéjew | Jósif, Jóssif | eminent Freemason | |

| Bilíbin | Bilíbin | diplomat | ||||

| Bolkónski 1 | Prince | Nikolái | Andreevich | Bolkónski | "The old prince" | |

| Bolkónski 2 | Prince | Andréj | Nikolayevich | Bolkónski | Andrúscha, André | Son of Bolkónski 1 |

| Bolkónski 3 | princess | Márja | Nikolayevna | Bolkónskaja m. Rostów | Marie, Máscha | Daughter of Bolkónski 1 |

| Bolkónski 4 | Princess | Elisabeth, Lisaveta | Karlowna | Bolkónskaja born Say | Lisa, Lise | Mrs. von Bolkónski 2, "the little princess" |

| Bolkónski 5 | Prince | Nikolái | Andreevich | Bolkónski | Nikóluschka, Nikólenka | Son of Bolkónski 2 |

| Bolkónski 6 | Mademoiselle | Amalia | Yevgenevna | Bouriénne | Amélie | Partner of Bolkónski 3 |

| Bolkónski 7 | Tíchon | Valet at Bolkónski 1 | ||||

| Bolkónski 8 | Jákow | Alpátych | Administrator at Bolkónskis, = Bolkónski 9 | |||

| Bolkónski 9 | Jacob | Alpátitsch | Administrator at Bolkónskis, = Bolkónski 8 | |||

| Davout | Marshal | Davoút, Duke of Eggmühl | Confidante of Napoleon | |||

| Denísow 1 | Wassíli | Dmítrych | Denísow, Deníssow | Wáska | Hussar officer, friend of Rostów 3 | |

| Denísow 2 | Lawrénti | Lavrúschka | Boy from Denísow 1, later from Rostów 3 | |||

| Dólochow 1 | Márja | Ivanovna | Dólochowa | |||

| Dólochow 2 | Fjódor | Ivanovich | Dólochow | Fédja | Son of Dólochow 1, officer and adventurer, drinking brother of Kurágin 4 | |

| Drubezkói 1 | Princess | Ánna | Micháilowna | Drubezkája | ||

| Drubezkói 2 | Prince | Borís | Drubezkói | Bórja, Borenka | Son of Drubezkói 1 | |

| Karágin 1 | Princess | Márja | Lwówna | Karágina | ||

| Karágin 2 | Júlja | Karágina | Julie | Daughter of Karágin 1 | ||

| Karatayev | Platon | Karatayev | a peasant prisoner of war | |||

| Kurágin 1 | Prince | Wassíli | Sergéjewitsch | Kurágin | Basile | |

| Kurágin 2 | Princess | Alína | Kurágina | Aline | Wife of Kurágin 1 | |

| Kurágin 3 | Prince | Ippolít | Vasilievich | Kurágin | eldest son of Kurágin 1 | |

| Kurágin 4 | Prince | Anatól | Vasilievich | Kurágin | youngest son of Kurágin 1 | |

| Kurágin 5 | princess | Helene | Vasilievna | Kurágina married Besuchowa | Lola | Daughter of Kurágin 1 |

| Kutusow | general | Micháil | Illariónowitsch | Kutusow | Commander in Chief of the Army | |

| Napoleon | Emperor | Napoleon I. | Bonaparte | |||

| Rostoptschín | Count | Rostoptschín | Governor of Moscow | |||

| Rostów 1 | Count | Ilya | Andreevich | Rostów | Elie | "The old count" |

| Rostów 2 | countess | Natalie | Rostówa born Shinschina | Frau von Rostów 1, "the old countess" | ||

| Rostów 3 | Count | Nikolái | Ilyich | Rostów | Nikólenka, Nicolas, Nikóluschka, Kolja, Koko | oldest son from Rostów 1 |

| Rostów 4 | Count | Peter, Pjotr | Ilyich | Rostów | Petja | youngest son from Rostów 1 |

| Rostów 5 | Vera | Ilyinichna | Rostówa, m. mountain | oldest daughter from Rostów 1 | ||

| Rostów 6 | Natalie | Ilyinichna | Rostówa married Besúchowa | Natascha | youngest daughter from Rostów 1 | |

| Rostów 7 | countess | Márja | Nikolayevna | Rostów born Bolkónskaja | Marie, Máscha | Daughter of Bolkónski 1 |

| Rostów 8 | Sófja | Alexándrowna | Sonja | Niece from Rostów 1 | ||

| Rostów 9 | Márja | Dmítrievna | Achrosimova | Relatives from Rostów 1 | ||

| Rostów 10 | Peter | Nikolájitsch | Schinschin | Rostów cousin 2 | ||

| Rostów 11 | Dimítri | Vasilievich | Mítenka | Administrator at Rostóws | ||

| Sachárych | Dron | Sachárych | Drónuschka | |||

| Timochin | Timochin | Infantry officer | ||||

| Túschin | Túschin | Artillery officer | ||||

| Tsar 1 | Tsar | Alexander I. | Pavlovich | Romanov | Tsar 1801-1825 | |

| Tsar 2 | Grand Duke | Konstantin | Pavlovich | Romanov | Brother of tsar 1 | |

| Tsar 3 | Empress Mother | Maria | Feódorovna | Mother of Tsar 1 | ||

| Tsar 4 | Ánna | Pavlovna | clipper | Annette | Lady-in-waiting of Tsar 3 |

reception

Stefan Zweig attributed the enormous impact of the novel to the fact that "the senselessness of the whole (the war) is reflected in every detail", that "chance decides a hundred times instead of calculation" of the clever strategists. Thomas Mann praised the gigantic epic work that could not have been accomplished in its time.

War and Peace was added to the ZEIT library of 100 books .

Adaptations

Opera

At the suggestion of Erwin Piscator in 1938, the Soviet composer Sergei Prokofiev composed the opera War and Peace in the 1940s , which was premiered in 1955 in what was then Leningrad . The same work was performed in 1973 as the first opera in the newly opened opera house in Sydney , Australia, famous for its architecture .

Film adaptations

- War and Peace (1956), an American film directed by King Vidor , with Audrey Hepburn (Natáscha), Henry Fonda (Pierre, see below) and Mel Ferrer (Andrej): Audrey Hepburn's portrayal of Natáscha was widely praised while the cast of the role of the young Pierre Besúchow (who as a "spectator" immediately got into the battle of Borodino, the fire of Moscow and the retreat of Napoleon) by Henry Fonda was viewed critically. The obligatory lovers were represented in this film by Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer. The monumental work had little success at the box office and, although it was nominated for costumes, camera and direction, did not receive any Oscars.

- War and Peace (1966–1967), a Soviet film adaptation of the same material, directed by Sergei Bondarchuk - the most elaborate film adaptation of the material to date in terms of costs, material and extras. The film received, as opposed to the American Erstverfilmung, 1969 the Oscar for best foreign language film .

- The last night of Boris Gruschenko (original title: Love and death ) from 1975, a satirical alienation of the novel War and Peace by and with Woody Allen .

- War and Peace as an English television series (Time Life Films London, 1972) in 20 episodes, ran on ARD in the early 1970s. Anthony Hopkins played the role of Pierre Visitow . Directed by John Davies .

- War and Peace (2007), four-part European film production. Director: Robert Dornhelm .

- War and Peace (2016), six-part English television production. Produced by BBC.

radio play

- War and Peace (1965), radio play by Westdeutscher Rundfunk . With Walter Andreas Schwarz , Gustel Halenke , Heinz Bennent , a. a. Director: Gert Westphal . Patmos, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 3-491-91203-2 .

- War and Peace (1967), radio play by the GDR radio . Radio play adaptation: Wolfgang Beck and Peter Goslicki ; Translation: Werner Bergengruen ; Director: Werner Grunow .

- War and Peace (2009), audio book (reading) by Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg . With Ulrich Noethen . Director: Ralph Schäfer. DAV, [Berlin] 2009, ISBN 978-3-89813-822-2 .

ballet

- War and Peace (2008), ballet by Wang Xinpeng , idea, concept and scenario by Christian Baier , music by Dmitri Schostakowitsch (premier ballet Dortmund 2008).

theatre

- War and Peace, Burgtheater Vienna, Austria. Version by Amely Joana Haag using the translation by Werner Bergengruen , directed by Matthias Hartmann , premiere on December 4, 2011.

- War and Peace, co-production of the Centraltheater Leipzig with the Ruhrfestspiele Recklinghausen, translation Barbara Conrad, director Sebastian Hartmann , premiere on May 20, 2012. The production was invited to the 2013 Berlin Theatertreffen.

- War and Peace, Mainfrankentheater Würzburg. Version and staging by Malte Kreutzfeldt using the translation by Werner Bergengruen, premiere on April 11, 2015.

expenditure

The table contains the first editions of the most important German translations. Deviating from this, some issues with special features or online versions are also listed.

The ISBN is given as an example. All translations are available in several editions. When dealing with the French text passages, the translators use different methods:

- Germanization. The French text passages are reproduced in German.

- Original reproduction in French without translation.

- Original reproduction in French with translation in footnotes or in a booklet.

The table information in the title column is based in some cases on an autopsy ( Bergengruen 1953 , Lorenz 1978 , Conrad 2010 ), otherwise on research in the catalog of the German National Library , alternatively in other library catalogs or in NN 1958 .

Note: An "E" after the year stands for "first edition".

| year | translator | output | French passages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1885 E. | Serious rigor | War and peace. Historical novel. Edited with the permission of the author; German translation by Dr. Serious rigor. 4 volumes. Published by A. Deubner, Berlin 1885–1886. | |

| 1892 | Serious rigor | War and peace. Historical novel. Edited with the permission of the author; German translation by Ernst Strenge. 2 volumes. 3. Edition. Reclam, Leipzig [1892]. | |

| 1892 E. |

Claire from Glümer Raphael Löwenfeld |

War and peace. [Translation by Claire von Glümer and Raphael Löwenfeld]. In: Leo N. Tolstoi's Collected Works. Volume 5-8. Wilhelmi, Berlin 1891-1892. | |

| 1893 E. | L. Albert Hauff (1838–1904) |

War and peace. Translated from Russian with the permission of the author by L. Albert Hauff. O. Janke, Berlin 1893 online version in the Gutenberg project. |

Germanized. |

| 1915 E. |

Hermann Röhl (1851–1923) |

War and peace. A novel in fifteen parts with an epilogue [transferred by Hermann Röhl]. 3 volumes. Insel-Verlag, Leipzig [1915 or 1916]; (= Construction paperbacks. Volume 2405). Construction paperback, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-7466-2405-1 . | Germanized. |

| 1921 |

Hermann Röhl (1851–1923) |

War and Peace: a novel in fifteen parts with an epilogue [transferred by Hermann Röhl]. In: Tolstoy's master novels. Volumes 4-7. Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1921. Online version at Zeno.org . |

Germanized. |

| 1924 E. | Erich Boehme (1879–1945) |

War and peace. Roman [transferred from Erich Boehme]. In: Leo N. Tolstoj: Complete edition in 14 volumes. Volume 2-5. J. Ladyschnikow Verlag , Berlin [1924]. | Original, without translation. |

| 1925 | Claire by Glümer Raphael Löwenfeld Ludwig Berndl |

War and peace. [Transferred from Claire von Glümer; Raphael Löwenfeld. Newly reviewed by Ludwig Berndl]. In: Lev N. Tolstoj: Poetical writings. Volume 7-10. Diederichs, Jena 1925. | |

| 1925 E. | Erich Müller | War and peace. A novel [German by Erich Müller]. 4 volumes. Bruno Cassirer, Berlin 1925. | |

| 1925 E. | Michael Grusemann (1877 - after 1920) |

War and peace. Novel in 4 volumes [German translation and epilogue by Michael Grusemann]. Wegweiser-Verlag, Berlin 1925 or 1926. | Original, without translation. |

| 1926 E. | Marianne Kegel | War and peace. Novel in 15 parts with an epilogue by Karl Quenzel. Translated from Russian by Marianne Kegel. 3 volumes. Hesse & Becker Verlag, Leipzig [1926]. | |

| 1928 E | Julius Paulsen Reinhold von Walter (1882–1965) Harald Torp |

War and peace. Novel in four volumes. Translated by Julius Paulsen, Reinhold von Walter and Harald Torp. Gutenberg Verlag, Hamburg [1928]. | |

| 1942 E |

Otto Wyss W. Hoegner |

War and Peace [translated from the Russian by Otto Wyss and partly by W. Hoegner]. 2 volumes. Gutenberg Book Guild, Zurich [1942]. | |

| 1953 E. |

Werner Bergengruen (1892–1964) |

War and peace. Novel. Complete unabridged edition in one volume, translated by Werner Bergengruen. Paul List Verlag, Munich 1953; 6th edition. Ibid 2002, ISBN 978-3-423-13071-4 . | Original, translation in footnotes. |

| 1954 E. |

Werner Bergengruen (1892–1964) Ellen Zunk |

War and peace. Novel. Translated by Werner Bergengruen, part 2 of the epilogue transmitted by Ellen Zunk. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1954. | |

| 1956 | Marianne Kegel | War and peace. Novel. Translated from the Russian by Marianne Kegel , Winkler, Munich 1956, ISBN 978-3-491-96054-1 . | Partly Germanized, partly original, without translation. |

| 1965 E |

Werner Bergengruen (1892–1964) Ellen Zunk |

War and peace. Novel. Translated by Werner Bergengruen, part 2 of the epilogue transmitted by Ellen Zunk. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1965 i. V. m. Paul List Verlag, Leipzig. | Original, translations and register of persons in supplements |

| 1965 | Erich Müller | War and peace. Roman [translated by Erich Müller. With an essay by Stefan Zweig ]. 2 volumes. Bertelsmann Lesering, Gütersloh 1925. | |

| 1970 |

Werner Bergengruen (1892–1964) |

War and peace. Afterword by Heinrich Böll . [Translated from Russian into German by Werner Bergengruen]. 2 volumes. List, Munich 1970. | Germanized. |

| 1978 E. |

Hertha Lorenz (* 1916) |

War and peace. Novel. Translated from Russian and edited in a contemporary way by Hertha Lorenz. Klagenfurt, Kaiser 1978; ibid 2005, ISBN 3-7043-2120-6 . | Germanized. |

| 2002 | Marianne Kegel | War and peace. Novel. Translated from the Russian by Marianne Kegel [with table of persons, chronological table, references, afterword and remarks by Barbara Conrad]. Patmos / Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96054-1 . | Partly Germanized, partly original, without translation. |

| 2003 E. |

Dorothea Trottenberg (* 1957) |

War and peace. The original version . Translated from the Russian by Dorothea Trottenberg. With an afterword by Thomas Grob. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-8218-0702-4 . | |

| 2010 E |

Barbara Conrad (* 1937) |

War and peace. Translated and commented by Barbara Conrad. 2 volumes. Hanser, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-446-23575-5 . Awarded the Leipzig Book Fair 2011 Prize (Category: Translation ). |

Original, translation in footnotes. |

Current issues

- War and peace. Translation Conrad (2010). dtv, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-423-59085-3 .

- War and peace. Translation Kegel (Patmos, 1956). Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96054-1 .

- War and peace. 4 volumes. Translation Boehme (1924). Diogenes, Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-257-21970-8 (text of the first two editions from 1868/69, with the corrections and the chapter division of the third edition from 1873).

- War and peace. 2 volumes. Translation Röhl (Insel, 1921; revised and abridged by Margit Bräuer, 2007). Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-458-35007-1 .

- War and peace. Translation Röhl (1921). Anaconda, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-86647-176-4 .

- War and Peace - Free E-Book. Null Papier Verlag, Neuss / Düsseldorf 2013, ISBN 978-3-95418-170-4 (Kindle), ISBN 978-3-95418-171-1 (Epub), ISBN 978-3-95418-172-8 (PDF) , Download.

Audio book

- War and peace. Reading by Ulrich Noethen, director: Ralph Schäfer. 4020 minutes, 54 CDs, Der Audio Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-89813-822-2 .

- War and peace. Radio play by WDR from 1965, 486 minutes, 10 CDs, Patmos, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 3-491-91203-2 .

literature

main characters

- Comprehensive dictionary of figures on war and peace by Anke-Marie Lohmeier based on the new translation by Barbara Conrad (Munich 2010) in the portal Literaturlexikon online .

- (Cord): Overview of the most important families and people [1] .

- Principal characters . In: Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace, translated from the Russian by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York 2007, pp. Xii – xiii ( PDF; 1.1 MB ).

Reviews

- (Jay): War and Peace [reading experience]. Blog from November 20, 2010 ( loomings-jay.blogspot.com [accessed on August 18, 2018]. The blog deals with the treatment of the French text passages in the translations by L. Albert Hauff, Marianne Kegel and Barbara Conrad.).

- Lothar Müller : Eh bien, mon prince. A great success, but only a preliminary review of the translation by Dorothea Trottenberg . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . November 17, 2003 ( buecher.de [accessed August 18, 2018]).

- Ulrich M. Schmid : Review of the translation by Barbara Conrad . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . October 4, 2010 ( nzz.ch [accessed on August 18, 2018]).

- Wolfgang Schneider: Masterfully translated (review of the translation by Barbara Conrad ) . In: Deutschlandradio Kultur from November 19, 2010 ( deutschlandfunkkultur.de [accessed on August 18, 2018]).

proof

- NN: LN Tolstoj: Bibliography of the first editions of German-language translations and of the works that have been published in German, Austria and Switzerland since 1945 / with an introductory article by Anna Seghers. Leipzig 1958.

- Léon Tolstoï: La guerre et la paix: roman historique, traduit par une Russe. Hachette, Paris 1879.

- Vladimir Tolstoy in the Leipzig House of the Book. (No longer available online.) In: juden-in-sachsen.de. May 2010, formerly in the original ; accessed on August 18, 2018 (no mementos). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) .

Web links

- War and Peace - full text in the Gutenberg-DE project .

- War and Peace - full text at Zeno.org based on the Röhl translation from 1921.

- Figure lexicon on war and peace by Anke-Marie Lohmeier in the online literature lexicon portal of the Saarland University.

- English audio book at LibriVox

- Horst-Jürgen Gerigk : Tolstoy's war and peace. Plea for a species-preserving ethic.

- Roland Marti: Lev N. Tolstojs Война и мир. In: Manfred Leber, Sikander Singh (eds.): Explorations between war and peace (= Saarbrücker literary-scientific lecture series. Volume 6). Universaar, Saarbrücken 2017, ISBN 978-386223-237-6 , pp. 147–174, urn : nbn: de: bsz: 291-universaar-1625 ( PDF; 2.1 MB ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lev Tolstoy: War and Peace . Dtv, Munich 2011, Volume 2, p. 1132 ff. List of historical actors.

- ^ A b Thomas Grob: Epilogue to Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace. The original version. Eichborn, Berlin 2003.

- ^ Ulrich Schmid : Lew Tolstoy. C. H. Beck, Munich 2010, p. 36.

- ↑ Information in the novel according to the Julian calendar .

- ↑ a b Umberto Eco : Quasi the same in other words - About translating . 3. Edition. No. 34556 . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-423-34556-9 , pp. 199 f . (translated by Burkhart Kroeber ).

- ↑ It is quoted, as in the following, from the B. Conrad translation. Lev Tolstoy: War and Peace. Dtv, Munich 2011

- ↑ He is missing the three children of Nikolai and the pregnant Marja: Andrjuscha, Mitja and Natascha. Two of Natascha's and Pierre's children are named: Lisa and the baby Petya.

- ↑ Sources used for the table of main characters, see here .

- ↑ Stefan Zweig: The writing of tomorrow's history. In: Ders .: The monotonization of the world: essays and lectures. Frankfurt 1976, p. 16 ff., Here: p. 26.

- ↑ Presentation on www.moviemaster.de .

- ↑ Concerning the first German translation by Ernst Strenge, the former tutor of Tolstoy's children, it was stated in a Tolstoy year at an event on the occasion of the Tolstoy year 2010: “The translation was probably not based on the original, but on the French text the Paskievich. The translation Strenges also contained “nothing superfluous”: no philosophical, military-strategic, or even in any way theoretical excursions by the writer. ”The Russian princess Irina Paskjewitsch (1832–1928) had published a French translation of War and Peace in 1879 .

- ↑ Published in the popular Reclam Universal Library series .

- ↑ The references from Zeno.org ("Tolstoj, Lev Nikolaevic: War and Peace. 4 vol., Leipzig 1922") are not sufficient to clearly identify the online version of Zeno.org. The catalog of the German National Library contains only one entry for a four-volume edition that was published in Leipzig around 1922, the translation by Hermann Röhl from 1921, DNB 560178573 . It can therefore be assumed that the online version of Zeno.org complies with this translation.