Chiricahua

The Chiricahua are a tribal group of Apaches in the southwest United States and (formerly) in the northwest of Mexico and include cultural - together with the Lipan , Jicarilla and Plains Apache (Plains Apache) (Engl. To the Eastern Apache - Eastern Apache ). Sometimes they are referred to together with the Mescalero living to the east as the Central Apache (English Central Apache ).

Their language, the Chiricahua or Ndee Bizaa, a dialect variant of the Mescalero-Chiricahua , belongs - together with the Navajo (Diné bizaad) and the Western Apache - to the Western branch of the South Apache languages of the Athapaskan language from the Na-Dené language family .

Surname

The tribal name "Chiricahua" in common use today comes from the language of the hostile Opata for the preferred settlement and hunting areas of at least three Apache local groups between the Dragoon Mountains and Chiricahua Mountains , which the Opata call Chiwi Kawi or Chihuicahui / Chiguicagui ("Mountain of the wild turkeys ”); later the Spaniards took over this topographical name for the Apache resident there (and a mountain range) as "Chiricahui / Chiricahua" . Other sources suspect the Nahuatl (meaning: "Big Mountain") as the origin of the name for the mountainous territory in southeastern Arizona and its inhabitants. The Western Apache living in the northwest called them Ha'i'ą́há / Aiáhal / Aiaho / Hiu-hah or Hák'ą́yé ("People of the Rising Sun", "People in the East"). The Chiricahua referred to foreigners (other Indians, Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans) as Enee, ⁿdáa or Indah / N'daa (this word has two possible meanings: "strange people, non-Apache" or "enemy" and: "eye" .) The Chiricahua called Europeans (with the exception of the Spaniards and Mexicans) Daadatlijende ("blue / green-eyed people") or Indaaɫigáí / Indaaɫigánde ("white-skinned or light-colored / pale-colored people", literally: "foreigners (hostile), non-Apache, with white / light skin "). Łigáí means "it is white" or "it is pale colored / light colored", the í at the end is mostly translated as "the one who is", but in the context of people mostly as "the group that ... is" (Hoijer, Harry (1943). "Pitch Accent in the Apachean Languages". Language).

The Chiricahua did not call themselves “Chiricahua” or even “Apache” but like most indigenous peoples simply (depending on the dialect) Nde, Ne, Néndé, Héndé or Hen-de (“The People”, “People”). They mostly identified themselves only as Bedonkohe (Bidankande) or as Chokonen (Tsokanende) , but distinguished themselves from neighboring Apache groups as a linguistic, cultural, relational and therefore partly political (mostly in the sense of mutual military support) unit with a common unit Identity as "Chiricahua". Today they designate with Chidikáágu (an Apache takeover of the Spanish word: Chiricahua) the members of the Chiricahua in general and with Indé all Apache (without distinction of tribal affiliation).

Today the term Apache is increasingly perceived as degrading and degrading, since this naming of the hostile Zuni for athapasques goes back to Apachu ("stranger, enemy"). The term Inde is therefore increasingly used for the various Apache groups and for the Navajo / Navaho Diné . It is the same with the Papago ( Tohono O'Odham ) or the Sioux ( Lakota , Nakota (also Nakoda ) or Dakota ).

residential area

Their former residential area was in southwestern New Mexico , southeastern Arizona and in the Sierra Madre Occidental in northern Sonora and Chihuahua . The various groups of Chiricahua roamed from the San Pedro River in Arizona in the west to the Rio Grande in New Mexico in the east and from the Salt River (Spanish: Rio Salado - 'salty river') and the upper reaches of the Gila River in the north to the Area of the Presidios Carrizal (around 41 miles south of Nuevo Casas Grandes ) in the northwest of Chihuahua, as well as in Sonora to the south of Bavispe, along the upper reaches of the Río Yaqui . Their areas included the Gila Wilderness, Sonora Desert , the Chihuahua Desert and the Sierra Madre Occidental, which the Chiricahua referred to as the Blue Mountains . The Zuni who previously lived here were driven out; hence their name for the athapasques as Apachu ('stranger' - 'enemy'). This word was adopted as Apaches by the Spaniards, Mexicans, and later Americans . In the northwest of the Chiricahua lived the Western Apaches and the Yavapai , in the north the Diné , in the east the Mescalero , in the south and southwest Tohono O'Odham , Hia-Ced O'Odham , Akimel O'Odham , Maricopa and Opata . There was a tense relationship with the Yavapai, the Western Apaches and the Diné, which, despite the linguistic and cultural affinity, often turned into enmity. The Chiricahua, on the other hand, always counted their eastern relatives, the Mescalero, among their reliable allies. Among the sedentary and arable tribes of the Upper Pima, Lower Pima, Opata, Maricopa and other sedentary Mexican tribes as well as later with the Spanish and Mexicans, the Chiricahua, like the other Apache groups, were known as robbers, thieves and cruel warriors and feared. The Chiricahua expanded their tribal area far south at the expense of the settled tribes, driving the Sobaipuri and Opata out of Arizona and large parts of northern Sonora.

Way of life

The Chiricahua were divided into four groups or bands split, which is usually of several local groups existed (local bands). These in turn are made up of two to five matrilocal and bilateral extended families, referred to by the Apaches as gotah . The gotahs were several nuclear families , each with a kowa ( Wickiup ) living in them, who lived together with other related families in a rancheria (Spanish: settlement). Hence the members of a group were related to most, if not all, of the others. Each extended family owned their own land by common law, where they made a living by hunting deer and other animals and gathering wild vegetables . When they reached the south-west, farming (only for the Chihenne ) and preying on raids joined this economic base. The Chiricahua often changed their settlements out of fear of retaliation and always lived in the protected highland regions, in canyons and mountain valleys. The southern groups, the Nednhi as well as some southern local groups of the Chokons , also protected their camps with guards. Only the local groups had elected leaders ( Nantan , sometimes women), but there were no recognized chiefs who could exercise all-encompassing power over the whole group. These leaders had prestige acquired through skill and persuasiveness. In addition, most of the Nantans were also diyins ( medicine men ) who had a special power (diya) . This enabled them to lead people and to consider the sacred aspects of the raid as well as the war. All known leaders like Cochise, Mangas Coloradas, Victorio, Juh were each only Nantans of their own local group. However, Cochise was never the chief of all Chokonen or Mangas Coloradas the one of all Chihennes. Cochise was Nantan and Diyin of the Chihuicahui local group of the Chokons. This fact by no means obliged Chihuahua, the leader of the Chokonen local group, to obey automatically, but he was free in his decisions and could, if he wanted, join Cochise temporarily. However, Victorio or Mangas Coloradas had enormous influence on neighboring local groups, but they could not command or conclude a binding contract for them.

For the Chiricahua there was a strict social difference between raids and military campaigns. The attacks were mostly carried out by one or more extended families, less often by local groups. Raids were always carried out when supplies in the camp ran out. The extended family organized a raid to get the food, ammunition, weapons, cattle, sheep, goats or horses they needed. Between 10 and 30 warriors took part in these ventures. They followed a pattern that would be called guerrilla tactics today. The aim, however, was by no means to kill his opponent. The warriors did not acquire a special status when they killed their enemy and they never took scalps . But they gained prestige when they managed to steal food supplies and horses for their families. Encounters with the enemy had to be avoided as much as possible. These forays were often accompanied by widows and women accompanying their husbands. The women were responsible for looking after the warriors and for securing the camp site. If the raid was successful, the Apaches drove the stolen cattle as quickly as possible to the safe mountain settlements of their homeland, with the warriors as scouts forming the vanguard and rear guard. Meanwhile, the cattle were herded by women and, if necessary, defended at gunpoint in the event of an attack. With the Spaniards, they were considered female warriors, because the martial skills of women in the defense of the booty as well as the camp was considerable.

A campaign was organized to avenge the death of another member of the group, and the leader was always a relative of the deceased. This leader did not have to be the leader of the group, but could be chosen by the grieving family. Sometimes a widow would take responsibility and lead the campaign. It was common for widows or women to go into battle with the men. Raids were mostly undertaken by large families, while campaigns were organized and carried out by a local group or even several local groups. 100 to 200 warriors could take part in the larger undertakings.

The views of the Apaches on war were generally in stark contrast to the ideas of the Plains Indians. There was no warrior societies, and those militant enthusiasm, even in a hopeless situation withstand wanting them was as strange as the custom of Coup -Zählens. Legendary figures such as Geronimo, Naiche or Cochise became famous because they repeatedly managed to outsmart the far superior US cavalry with cunning.

Religion and culture

Like most Indians, the Chiricahua were deeply religious people. The spirits, which they believed would animate all of nature, had to be appeased regularly through ceremonies in private circles. Most important of the few public ceremonies, however, was the ritual dance when a girl reached puberty . The custom required that every girl should be given this honor. The scattered members of a group then came together and thanked the spirits that the girl had reached childbearing age in good health and could therefore help secure the future of the tribe.

history

The legend

In the beginning the world was in darkness and there was neither the sun nor the day. In the everlasting darkness neither the moon nor the stars shone. Yet there were many kinds of animals in the world, including terrible, nameless monsters. No humans could live in this world because they would have been killed instantly by snakes and other wild animals. But there was one child who was not eaten by any beast. His mother, the white-painted woman (English: White painted Woman) had hidden it in front of a man-eating dragon. As the boy grew up, he went hunting. One day he met the dragon in the mountains. The boy shot three arrows through his scale armor and even stabbed his heart with a fourth. The name of this hunter was Inde , the first of his tribe. These or similar stories of creation are everywhere among the Apaches.

Early history

Athapaskan speaking peoples were the last major Native American group to come to the southwestern United States . Originally at home in northwestern Canada and Alaska , they invaded the southwest in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, not too long before the arrival of the Spaniards . Without realizing it, Francisco de Coronado and his expedition brought a new form of locomotion to the land of the Apaches, the horse, which they should use more than any other tribes in the Southwest. With the horse they got a pack animal, a new source of food and a reliable transport animal with which they were able to expand their previous radius of action considerably. The entire tribal area was divided among a loose league of individual groups that sometimes even fought. Yet they were seen as a single enemy by the peoples with whom they came into conflict.

The Chiricahua resisted colonization through raids and acts of violence. The white intruders had to withdraw temporarily again several times. Their extensive raids deep into Mexico were feared and notorious. Early Spanish accounts referred to these Indians as Sumas, Jocomes, and Janos rather than Apache, but they were undoubtedly Athapaskan speaking groups, probably various Chiricahua groups, possibly some Mescalero groups as well. In the 18th century they were commonly referred to as Apache.

Attempts to proselytize these tribes ended in a large-scale rebellion in 1684. To protect their settlements from renewed attacks by the Chiricahua groups, the Spaniards built a chain of fortified military posts (Spanish: Presidio ) in northern Mexico. But defensive warfare was ineffective against the guerrilla tactics of the Indians. In addition, the Apaches were not interested in driving the Spaniards out of the country, but rather in capturing horses, cattle and food. Punitive expeditions against the Chiricahua in their own country were consistently unsuccessful because the Indians cleverly avoided open fighting. In particular, the Nednhi, who lived farthest south and therefore near the settlements, were often victims of Spanish and later Mexican retaliatory actions for attacks by other Apache groups. However, this had the consequence that the Nednhi only militarized themselves even more. They completely gave up farming and lived only from looting and robbery. They even acquired a wild reputation among the other Apaches, were considered brutal and pure robbers, who also took in and integrated outcasts from other groups.

19th century

The Spaniards and Mexicans later tried a new tactic. They encouraged the Apaches to settle near the presidios, where they were given food, blankets, clothing and alcohol four times a year until they became addicted. The plan was successful until 1811 when the Mexicans had to stop deliveries for lack of money. Immediately the Chiricahua and other Apache groups resumed the raids and these were even more numerous and extensive than before. Plundering Apaches moved as far as Hermosillo in Sonora and in 1848 Tubac had to be evacuated along with many other Mexican settlements.

When the northern provinces of Mexico fell to the United States in 1848 through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo , the Chiricahua initially regarded the Americans as friends and allies against the hated Mexicans. But after gold and silver discoveries in Arizona in the 1850s, tensions arose between American gold prospectors and Apaches. The biggest problem, however, was the US government's demand that the Chiricahua stop raiding Mexican settlements across the border.

Cochise

In 1858 the transcontinental stagecoach line Butterfield Overland Mail was established, which led across the land of the Chiricahua over the strategically important Apache Pass . With the consent of Cochise , a Chokonen chief , a post office was set up there. But in 1861 there was an incident that resulted in open war between the US Army and Cochise. Cochise, who came to Apache Pass with his family, was falsely accused of kidnapping a 10-year-old boy. George N. Bascom , an ambitious young lieutenant, arrested Cochise and his family as a result. Cochise escaped and tried to free the captured family members. But now the situation escalated. Cochise and some warriors ambushed a truck train and killed eight Mexican wagoners. Then Lieutenant Bascom had Cochise's brother and two nephews hanged. Cochise decided to drive the Americans out of his country again and gathered his warriors for a bloody campaign. Coming from their hiding places in the mountains, they ambushed freight caravans, stagecoaches, mines and smaller settlements. Settlers across the region fled, and two months later Cochise and his Chiricahua had killed an estimated 150 whites.

Cochise allied with Mangas Coloradas , a Bedonkohe chief, and waged a relentless guerrilla war against the whites for 10 years. While the exact number of people who fell victim to Cochise was never known, the number was certainly high enough to cause major concern among federal authorities. In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant sent a Civil War general , Oliver Otis Howard , to Cochise, and eventually a peace treaty was signed. The Chiricahua were allowed to keep their way of life, their weapons and their traditional hunting ground. The reservation included the Chiricahua and Dragoon Mountains , where the tribe had lived and hunted for many generations. In 1874, Cochise died at the age of 51. His eldest son, Tahzey, agreed to move to the San Carlos Reservation on the Gila River .

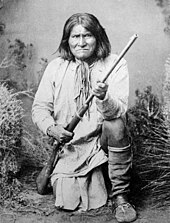

Geronimo

But some leaders of other Chiricahua groups refused to give up the free life, including Juh , the leader of the Nednhi and a Bedonkohe holy man (Diyin) named Geronimo , whose real name was Gokhlayeh (One Who Yawns) . Like Geronimo, more and more Chiricahua warriors used the reservation merely as a kind of refuge. They went on their forays into nearby Mexico and then returned when the ground there got too hot under their feet. Often they brought stolen horses and cattle with them, which they sold to their tribesmen on the reservation.

In the following years Geronimo made a name for himself in the history of the West, which made him known far beyond the borders of Arizona. He was considered the last resistance fighter who was determined to fight for his freedom and the traditional way of life longer and harder than any other Indian. When his raids on Mexico and the United States became intolerable in 1882, both states agreed that the Indian-hunting troops of both countries would be entitled to pursue up to 200 miles (320 kilometers) into the other country's territory.

The commander in chief of the American troops was General George Crook , who had already proven himself in other campaigns against Indians. Crook developed his own tactic that would soon prove to be successful. He was convinced that you need an Apache to catch another Apache. So he strengthened his cavalry troops by 193 Indian scouts , whom he recruited on the reservation. Even the hunted Apaches did not consider these scouts as traitors, because after all, individual groups had always fought with each other and the deadly boredom in the reservation did the rest. This innovation soon paid off when a group of these scouts discovered an Apache camp in the Mexican mountains in May 1883 and the warriors were overwhelmed. Geronimo was now ready to negotiate with Crook. The general knew that the Chiricahua lived all over the country and gave Geronimo two months to gather his people and return them to the reservation. Geronimo kept the promise and only returned after nine months, in March 1884.

In an 1884 letter to his superiors, Crook proudly notes that "for the first time in history every member of the Apache tribe lives in peace." But the peace was short-lived. A year later Geronimo broke out again and took 42 men and 92 children and women with him. Crook gathered a force unlike any of the so-called Apache Wars - 20 cavalry units and more than 200 scouts, more than 3,000 men in total. Throughout the winter of 1885/1886, Crook's troops hunted the enemy in the Sierra Madre in Mexico. In March 1886 Geronimo was persuaded to meet Crook a few kilometers south of the border. Crook and Geronimo negotiated for two days and again Geronimo agreed to return to the reservation. But at night and in the rain, he changed his mind and ran away again, with 20 warriors and 18 women and children who fled with him.

Crook had been attacked by the press for some time for being too humane to the Apaches. When his superior, General Philip Sheridan , reprimanded him for it, Crook resigned from his command. He was succeeded by General Nelson Miles . He even assembled 5,000 men to hunt Geronimo and had 30 mirror telegraphs erected on the mountains . When the Chiricahua skillfully evaded this mass presence of human hunters and continued their raids at will, panic spread among the inhabitants of the region. In July 1886 Geronimo took a break in the middle of the Sierra Madre and had not lost a single man. In late August he was finally ready to speak to General Miles.

Surrender and internment

On September 3, 1886, Geronimo surrendered and was sent to Florida as a prisoner of war together with another 381 Chiricahua, hand and foot shackled with chains . Men, women and children were separated. The women were interned by the US authorities at Mt. Vernon Barracks, Alabama, the men at Fort Pickens , Florida, and the children were sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle , Pennsylvania, "to be civilized and educated." Many of them died of illness, mainly due to the unfamiliar climate. In 1894 Geronimo and the rest of the Chiricahua were finally transferred to a military prison in Fort Sill , Oklahoma. Geronimo himself was demoted to exhibit and appeared in President Theodore Roosevelt's inauguration parade in 1901 and at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 , the St. Louis World's Fair . He died on February 17, 1909 in Fort Sill without ever having seen his homeland again.

In the course of the 20th century, the story of the Chiricahua and their leaders served as the material for numerous Hollywood western films and wild west novels .

Demographics

At the beginning of the 16th century all groups of the Chiricahua Apache were estimated at around 3,000 people, but the constant wars against Spaniards, Mexicans and later Americans, as well as several severe smallpox and malaria epidemics decimated the individual groups again and again. By the middle of the 19th century, however, they were able to stabilize their population through the adoption and integration of stolen Indian and white children and women as well as Indians fleeing from Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans.

In the 1860s, the Chiricahua Apache numbered around 3,000 tribe members and could muster around 750 warriors. As a result of constant fighting with Mexicans and Americans, as well as neighboring tribes, the number of Chiricahua steadily decreased. In the 1870s they could only provide 600 warriors, divided into the four independently acting bands : Chihenne (about 175 warriors), Chokonen (about 150 warriors), Southern Chiricahua (about 150 warriors) and the Bedonkohe as the smallest group (about 125 Warrior).

Of the approximately 25,000 Apaches nationwide today, around 3,500 call themselves Chiricahua.

Todays situation

The descendants of the various Chiricahua bands are now organized into two federally recognized tribes and a state recognized tribe recognized by the state of Alabama :

United States - Oklahoma

- Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

- The Fort Sill Apache Tribe (also Fort Sill Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache Tribe ) consists of descendants of the Chiricahua Apache (Chokonen, Chihenne, Bedonkohe and Nednhi) interned as prisoners of war from 1886 to 1912, who were transferred to the military prison in Fort Sill in Oklahoma in 1894 were brought. The Kiowa , Comanche and Kiowa Apache , who were already settling here , made parts of their reservation land available to their former enemies, the Chiricahua Apache. In August 1912, prisoner-of-war status was revoked and in 1913, 187 Fort Sill Apache moved to the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico to live with their relatives, the Mescalero Apache. 84 Fort Sill Apache remained in Oklahoma as a prisoner of war and was not released until 1914. In the 1970s, a land claim agreement allowed a tribal constitution to be passed and some land in Oklahoma as well as former tribal land in New Mexico and Arizona to be acquired. In 1977 they were officially recognized as a tribe as the Fort Sill Apache Tribe . Today there are around 670 tribal members, half of whom are over 18 years old. About 300 live in Oklahoma with the remainder spread across the United States, England, and Puerto Rico.

- The tribe now operates two casinos , the Fort Sill Apache Casino in Lawton, Oklahoma and the Apache Homelands Casino in Akela, New Mexico

United States - New Mexico

- Mescalero Apache Tribe

- The Mescalero Apache Reservation is located in south-central New Mexico, is around 1,864 km² and lies at an altitude of around 1,600 m to 3,650 m above sea level. The high mountains are part of the Sacramento Mountains , with the Sierra Blanca Peak (3,652 m), which is sacred to the Mescalero Apache. The Mescalero Apache Tribe today officially consists of three separate groups, which represent the following formerly independent tribes: the Mescalero Apache , the Chiricahua Apache and the Lipan Apache .

- The Twid Ndé (Tú'é'diné Ndé, No Water People, Tough People of the Desert) of the Lipan Apache had already allied themselves with the Mescalero before the reservation period and merged with the Mescalero around 1850 as Tuetinini . Chief Magoosh's local group of Tu'tssn Ndé (Tú sis Ndé, Kúne tsá - Big Water People, Great Water People) also sought refuge with the Mescalero around 1850, and in 1904 Chief Venego fled with his local group from Zaragoza in Mexico. Both groups merged with the Mescalero to form the Tuintsund .

- In 1913, Fort Sill Apache Chiricahua (Chokonen, Chihenne, Bedonkohe and Nednhi) moved to the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico to the Mescalero Apache. In August 1912, prisoner-of-war status was revoked. While the Mescalero had previously entered into some mixed marriages with Chihenne and Lipan, they initially had a tense relationship with the Chokonen, Bedonkohe and Nednhi. In the course of time, however, as a result of living together in a small space, more and more friendly and familiar contacts between the various groups developed and strong and close relationships developed among each other. Finally, in 1964, all Apache in the reserve, regardless of their origin, were recognized as Mescalero.

- The tribe operates the Ski Apache ski resort as well as the neighboring hotel and casino for tourist traffic , the Inn of the Mountain Gods Resort and Casino . They also built a cultural center, the Cultural Museum, near their administrative center in Mescalero, New Mexico. The tribe owns an even larger museum in Dog Canyon south of Alamogordo , New Mexico. According to the census , there were 3,156 tribal members in 2000 and 3,979 in 2013.

United States - Alabama

- MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI)

- In 1979, the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians became the first tribe to be recognized as a tribe by the state of Alabama. The name MOWA refers to the names of the Mobile Counties and Washington Counties , which are now the reservation areas.

- The approximately 1.2 km² MOWA Choctaw Reservation is located along the Mobile River and Tombigbee Rivers between the small communities of McIntosh, Mount Vernon and Citronelle in southwest Alabama, north of Mobile . They are descendants of Choctaw , Muskogee (also Creek), Chickasaw , Cherokee and Chiricahua Apache, who were interned as prisoners of war in the Mt. Vernon Barracks from 1887 to 1894. The majority have Choctaw ancestors from Mississippi and Alabama, who escaped forced relocation to Indian territory at the time of the Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty in 1830 . In addition to the tribal members in the reservation, about 3,600 live in 10 small settlements near the reservation. According to the United States Census 2000 , the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians has around 6,000 tribal members.

Today (as of 2007) 175 Chiricahua Apache speak their mother tongue, Chiricahua , a dialect variant within the Mescalero-Chiricahua Apache, 149 of them in the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico, the rest in Fort Sill in Oklahoma.

Chiricahua bands and local groups

There were four bands with the Chiricahua, which in turn consisted of several local groups ( gotahs , English local bands ):

Chokonen , Chukunende or Tsokanende ( Ch'ók'ánéń , Tsoka-ne-nde , Tcokanene , Chu-ku-nde , Chukunen , Ch'úk'ánéń , Ch'uuk'anén - "Ridge of the Mountainside People - People of the Mountain slopes ", also Chiricaguis , real or central Chiricahua )

- Chokonen local group (lived west of today's Safford in Arizona, along the upper reaches of the Gila River , and northeast along the San Francisco River to the Mogollon Mountains in New Mexico and in the San Simon Valley in the southwest, northeast local group )

- Chihuicahui Apache (derived from the Opata language: “Chiwi Kawi” or “Chihuicahui / Chiguicagui”: “Mountain of the wild turkeys”, making it the preferred settlement and hunting area of at least three local groups between the Dragoon Mountains and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona described west of the San Pedro River, their western border was formed by the present-day towns of Engin, Benson, Johnson and Willcox, roamed north to the San Simon River and east to southwest New Mexico, dominated the Huachuca Mountains (in Apache: "Donner Berge"), the southern Pinaleno, as well as the Winchester, Dos Cabezas, Chiricahua, Dragoon and Mule Mountains, today the Chiricahua National Monument is located on a former tribal area, own name possibly Shaiahene , in English also known as Huachuca Mountains Apache as Cochise Apache , southwest local group )

- Cai-a-he-ne local group ("Sun Goes Down People" - "People of the setting sun, ie in the west", lived farthest west of all Chihuicahui, western local group, Cochise's group)

- Tse-ga-ta-hen-de local group ("Rock Pocket People", lived in the Chiricahua Mountains)

- Dzil-dun-as-le-n local group ("Rocks At Foot of Grass-Expanse", lived in the Dragoon Mountains)

- Dzilmora local group (lived in the Alamo Hueco, Little Hatchet and in the Big Hatchet Mountains in southwest New Mexico, known by the Apache as Dzilmora , southeastern local group )

- Animas local group (lived south of the Gila River, west of the San Simon Valley in the Peloncillo Mountains along the Arizona-New Mexico border south to Guadalupe Canyon and east in the Animas Valley and the Animas Mountains in southwest New Mexico, southern local group )

- Local group not known by name (lived in northeastern Sonora, Mexico, and in adjacent Arizona, in the Guadalupe Canyon, along the San Bernardino River, in the northwestern parts of the Sierra San Luis, in the Batepito Valley with the Sierra Pitaycachi, east of Fronteras , as theirs Fortress)

- Local group not known by name (lived east of Fronteras in the Sierra Pilares de Teras in Sonora )

- Local group not known by name (lived in the Sierra de los Ajos northeast of the Sonora River, along the Bavispe River north to Fronteras)

Bedonkohe , Bidánku or Bidankande ( Bi-dan-ku - "In Front of the End People - people who settle on the front line" or Bi-da-a-naka-enda - "Standing in front of the enemy - people that on the border of enemy settled ", lived in western New Mexico in the Mogollon Mountains and Tularosa Mountains between the San Francisco River in the west and the Gila River in the southeast, as their preferred retreat often the Mogollon Mountains were, they were also Mogollon Apaches called , just like other local Apache groups along the Gila River and in the Gila Mountains, they were often referred to as Gileños or Gila Apaches , northeastern Chiricahua )

- local group not known by name (lived in the Mogollon Mountains)

- local group not known by name (also lived in the Mogollon Mountains)

- local group not known by name (lived in the Tularosa Mountains)

Chihenne , Chihende or Tchihende ( Chi-he-nde , Tci-he-nde , Chíhéne , Chííhénee ' - "red-painted people" or "people of the red color", the name could refer to the red coloration of the copper-bearing tribal area, often as Copper Mine, Warm Springs / Ojo Caliente Apache, Mimbreños / Mimbres, Gila Apaches, Eastern Chiricahua )

- Warm Springs Apache (with Warm Springs or in Spanish Ojo Caliente - "Hot / Warm Springs" was their preferred retreat area - the Hot Springs area - referred to, the Apache themselves called the area Tih-go-tel - "Four broad plains")

- Northern Warm Springs local group (lived northeast of the Bedonkohe in the Datil, Magdalena and Socorro Mountains, the Plains of San Agustin, and in the north from today's Quemado east to the Rio Grande , northern local group )

- Southern Warm Springs local group (also: Real Warm Springs , settled near Ojo Caliente near today's Monticello , between the Cuchillo Negro Creek and the Animas Creek, ruled the San Mateo and Negretta Mountains as well as the Black Range west of the Rio Grande to the Gila River, used the thermal springs near today's Truth or Consequences , formerly known as Hot Springs , therefore called Warm Springs Apaches or Ojo Caliente Apaches , southern local group )

- Gila / Gileños Apache (often used as a collective term for all local groups of the Chiricahua and Western Apache along the Gila River and in the Gila Mountains )

- Ne-be-ke-yen-de local group (“Country of People” or “Earth They Own It People”, also: Copper Mine Apaches, most likely a mixed Chihenne-Bedonkohe local group, lived southwest of the Gila River, especially with the Santa Lucia Springs in the Burro Mountains, northwest of present-day Silver City , ruled the Pinos Altos Mountains, Pyramid Mountains and the area around today's ghost town of Santa Rita del Cobre along the Mimbres River in the east, formerly known as Gileños or Gila Apaches , they were named after the Discovery of high-yield copper mines near Santa Rita del Cobre, usually referred to as Copper Mine Apaches ("Copper Mining Apaches"); western local group )

- Mimbres / Mimbreño local group (lived in southeastern western New Mexico, between the Mimbres River and the Rio Grande in the Mimbres Mountains and the Cook's Range, therefore referred to as Mimbres Apaches or Mimbreño Apaches , eastern local group )

- Local group not known by name (lived in southern New Mexico in the Pyramid Mountains and in the Florida Mountains called by the Chihenne Dzlnokone - "Long Hanging Mountain", migrated in the east to the Rio Grande and in the south to the Mexican border, southern local group )

Nednhi , Nde'ndai or Ndendahe ( Ndéndai , Nde-nda-i , Nédnaa'í , Ndé'indaaí , Ndé'indaande , Ndaandénde - "hostile people, people who cause trouble", often referred to as Bronco Apaches, Sierra Madre Apaches , Southern Chiricahua ).

- Nednhi Apache (lived in the northwest of Chihuahuas, northeast of Sonora and in the southeast of Arizona and roamed deep south into the Sierra Madre, probably called themselves Dzilthdaklizhéndé - "Blue Mountain People - people of the Blue Mountains, ie the Sierra Madre", northern local group , divided in three local groups)

- Janeros local group (also: real Nednhi , lived in the northwest of Chihuahua and northeast of Sonora, south in the Sierra San Luis, Sierra del Tigre, Sierra de Carcay, Sierra de Boca Grande, west across the Aros River to Bavispe, in the east along the Janos River and Casas Grandes River to Lake Guzmán in the northern Guzmán Basin, traded preferentially with the Presidio Janos, probably called themselves Dzilthdaklizhéndé - "Blue Mountain People - people of the Blue Mountains, ie the Sierra Madre", northern local group)

- Tu-ntsa-nde local group ("Big Water People - people along the great water, ie the Aros River", their fortress called Guaynopa was in a loop of the Papigochic River (Aros River) east of the border of Sonora near a mountain called Dzil -da-na-tal - "Mountain Holding Head Up And Peering Out", smallest local group)

- Local shark group ("People of the Rising Sun. ie of the East", lived in the Peloncillo Mountains , Animas Mountains and Florida Mountains in southeast Arizona and in the panhandle of New Mexico and south to the adjacent mountains in northeast Sonora and the plateaus in the northwest from Chihuahua - possibly identical to the also mentioned "Hakaye local group" in the same area)

- Carrizaleños local group (referred to by the Chiricahua as Gol-ga-he-ne - "Open Place People - People of the Plains" or Gul-ga-ki - "Prairie Dog People - People of the Prairie Dogs ", due to their preference in the plains in the Living north of Chihuahua, between the Presidios of Janos to the west and Carrizal and El Carmen, and Lake Santa Maria to the east, south to Corralitos, Nuevo Casas Grandes and Agua Nuevas, 60 miles north of Chihuahua , dominated the southern Guzmán Basin as well the mountain ranges along the Casas Grandes River, San Miguel River, Santa Maria River and Carmen River, were probably called Tsebekinéndé - "Stone House People / Rock House People", southeast local group )

- Pinaleños local group (lived in the northern border area between Sonora and Chihuahua, south of Bavispe, between the Bavispe River and Aros River, ruled the Sierra Huachinera, Sierra de los Alisos and Sierra Nacori Chico. These mountains have a large forest of Apache pines - hence they were called Pinaleño Apaches or Pinery Apaches , southwest local group )

The Carrizaleňo -Nednhi not only shared overlapping areas around Casas Grandes and Agua Nuevas with the Tsebekinéndé , a southern Mescalero group, often called Aguas Nuevas by the Spanish , but also shared the same name - Tsebekinéndé. The Spaniards, Mexicans, and Americans often confused these two different Apache groups with one another. The same applies to the Janeros -Nednhi (Dzilthdaklizhéndé) and the northeast and eastern Dzithinahndé of the Mescalero.

The local groups of Chokonen , Chihenne , Bedonkohe listed above either as "not known by name" or under Spanish / English "names" as well as those of up to three other local groups of Nednhi - each according to their leaders, their area of residence or a special characteristic, for example the painting or clothing - were named, were destroyed or blown up early by the actions of the Mexican and later the US army, so that their names were no longer known to the surviving Apache at the end of the 19th century.

Either they were destroyed in operations by the Mexican and American armies (1840-1870), such as the Pinaleño-Nednhi, or had joined other less decimated local groups. The dispersed Carrizaleños Nedhni either joined their northern relatives, the Janeros, or local Mescalero groups in the southeast and northeast. During the last fighting of the Chiricahua, many local groups were decimated to such an extent that they were no longer able to survive alone in the fight and to maintain their security and freedom. During this time, the Janero-Nednhi under Juh became a reservoir for the smallest groups who wanted to continue the fight.

Well-known leaders and chiefs of the Chiricahua

Chocons:

- Cochise (also Cheis or A-da-tli-chi - 'hardwood', * between 1810 and 1823; † June 8, 1874)

- Naiche ('the rogue', 'the mischief maker', * between 1856 and 1858; † 1919, younger son of Cochise)

- Ulzana (also Josanni or Jolsanie , segundo of his brother Chihuahua, * in the 19th century in the USA; † 1909)

- Chihuahua (in Apache: Kla-esh , brother of Ulzana)

Bedonkohe:

- Geronimo (Spanish invocation of St. Jerome, Gokhlayeh or Goyaałé - 'the yawning', * June 16, 1829, † February 17, 1909)

Chihenne:

- Mangas Coloradas (Spanish: 'Red Sleeves', English Red Sleeves , derived from Apache: Kan-da-zis Tlishishen (' Pink Shirt '), because he always wore a red shirt in combat; also Dasoda-hae -' He Just Sits There ', * 1797 - † January 18, 1863)

- Victorio (Spanish for 'the winner', 'the victorious', Bidu-ya or Beduiat , * around 1825, † October 14, 1880)

- Nana (Spanish 'grandmother', Haskenadilta - 'Angry, He is angry / angry', also Kas-tziden - 'Broken Foot'; * around 1800, † 1894)

- Ka-ya-ten-nae ( Kadhateni , Kieta - 'Fights Without Arrows', 'Cartridges All Gone', * 1858 - † Jan. 1918)

- Loco (Spanish for 'the crazy', 'the daring, brave', in Apache: Mahtank )

Nednhi:

- Juan Jose Compa

- Juh (also Hu , Ho , Whoa , Jui , read: Hoo, in Apache Tan-Dɨn-Bɨl-No-Jui - 'He brings many (stolen) things with him', also Ya-Natch-Cln - 'the farsighted one' , * around 1825; † November 1883)

- Natiza

See also

literature

- William C. Sturtevant (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians , Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC

- Alfonso Ortiz (Ed.): Southwest Vol. 9, 1979 ISBN 0-16-004577-0

- Alfonso Ortiz (Ed.): Southwest Vol. 10, 1983 ISBN 0-16-004579-7

- Editor of Time-Life Books: The Spanish West , Time-Life Books Inc., 1976

- Alvin M. Josephy jr .: 500 Nations , Frederking & Thaler GmbH, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-89405-356-9

- Alvin M. Josephy jr .: The world of the Indians , Frederking & Thaler GmbH, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-89405-331-3

- Editing of Time-Life Books: The Great Chiefs , Time-Life Books Inc., 1978

- John Gattuso (Ed.): Indian Reservations USA , APA Guides, RV Reise- und Verkehrsverlag, 1992

- Tom Bathi: Southwestern Indian Tribes , KC Publications, Las Vegas , 1995

- Siegfried Augustin : The history of the Indians , Nymphenburger, Munich 1995

- Dee Brown: Bury my heart at the bend of the river , Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 1972

- Edward F. Castetter, Morris E. Opler: The ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache: The use of plants for foods, beverages and narcotics ; Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest, 3; Biological series, Volume 4, No. 5; Bulletin, University of New Mexico, whole, (No. 297); Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1936

- Harry Hoijer, Morris E. Opler: Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache texts ; The University of Chicago publications in anthropology; Linguistic series; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1938; Reprint: Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970; New York: AMS Press, 1980; ISBN 0-404-15783-1 .

- Morris E. Opler: An analysis of Mescalero and Chiricahua Apache social organization in the light of their systems of relationship ; Dissertation at the University of Chicago, 1933

- Morris E. Opler: The concept of supernatural power among the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apaches ; American Anthropologist 37/1 (1935), pp. 65-70.

- Morris E. Opler: The kinship systems of the Southern Athabaskan-speaking tribes ; American Anthropologist 38/4 (1936), pp. 620-633.

- Morris E. Opler: An outline of Chiricahua Apache social organization ; in: F. Egan (ed.): Social anthropology of North American tribes ; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934; Pp. 171-239

- Morris E. Opler: A Chiricahua Apache's account of the Geronimo campaign of 1886 ; New Mexico Historical Review 13/4 (1938); Pp. 360-386.

- Morris E. Opler: An Apache life-way: The economic, social, and religious institutions of the Chiricahua Indians ; Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1941. Reprint: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994; ISBN 0-8032-8610-4 .

- Morris E. Opler: The identity of the Apache Mansos ; American Anthropologist 44/1 (1942); P. 725.

- Morris E. Opler: Chiricahua Apache material relating to sorcery ; Primitive Man, 19 / 3-4 (1946); Pp. 81-92.

- Morris E. Opler: Mountain spirits of the Chiricahua Apache ; Masterkey 20/4 (1946); Pp. 125-131.

- Morris E. Opler: Notes on Chiricahua Apache culture, I: Supernatural power and the shaman ; Primitive Man 20 / 1-2 (1947); Pp. 1-14.

- Morris E. Opler: Chiricahua Apache ; in A. Ortiz (ed.): Southwest ; Handbook of North American Indians , 10; Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1983; Pp. 401-418

- Morris E. Opler, David H. French: Myths and tales of the Chiricahua Apache Indians ; Memoirs of the American folk-lore society, 37; New York: American Folk-lore Society, 1941. Reprint: ME Opler (ed.), Morris by Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994; ISBN 0-8032-8602-3 .

- Morris E. Opler, Harry Hoijer: The raid and war-path language of the Chiricahua Apache ; American Anthropologist 42/4 (1940); Pp. 617-634.

- Albert H. Schroeder: A study of the Apache Indians: Parts IV and V ; Apache Indians, 4: American Indian ethnohistory, Indians of the Southwest; New York: Garland, 1974

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ It is often stated that all Apache had Americans and European settlers (with the exception of the Mexicans) as "Bi'ndah-Li'ghi '/ Bi'nda-li'ghi'o'yi" (mostly as pinda-lick-o- yi - "white eyes" reproduced), but this name seems to come from bands of the Mescalero or Lipan Apache.

- ↑ The three versions of the names of the individual Chiricahua bands can be explained in this way: 1st variant (e.g. Chokonen) is the spelling commonly used today, 2nd variant (Chukunende) is used by the Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 3 Variant (Tsokanende) is another common transcription

- ↑ The Chokonen were led by Chihuahua and his segundo and brother, Ulzana, in the middle of the 19th century .

- ↑ For the Apache only the Chokonen and three Chihuicahui local groups of the Chokonen Band were “true Chiricahua”; the Chihenne, Bedonkohe and Nednhi bands, which today also belong to the Chiricahua, as well as the other local Chokonen groups were regarded as related groups, but not as Chiricahua

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jessica Dawn Palmer: The Apache Peoples. A History of All Bands and Tribes Through the 1880s. Mcfarland, 2013, ISBN 978-0786445516 .

- ↑ José Cortés: Views from the Apache Frontier: Report on the Northern Provinces of New Spain 1799, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-2609-8

- ↑ Homepage of the Fort Sill Apache Tribes

- ↑ 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations - Fort Sill Apache Tribe ( Memento from May 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Homepage of the Fort Sill Apache Casino

- ↑ Homepage of the Apache Homelands Casino ( Memento of the original from October 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Homepage of the Ski Apache Resort

- ↑ Homepage of the Inn of the Mountain Gods Resort and Casino

- ↑ Homepage of the Cultural Museum

- ^ US Department of the Interior - Indian Affairs - Mescalero Agency

- ↑ Homepage of the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians

- ↑ Homepage: Fort Sill Apache Tribe - Tribal History.

- ^ Gregor Lutz: 27 years of captivity. Geronimo and the Apache Resistance. Books on Demand, 2012, ISBN 978-3848228966 , pp. 8-13.

- ↑ Edwin R. Sweeney: Cochise: Chiricahua Apache Chief. University of Oklahoma Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8061-2606-7 .

- ↑ Kathleen P. Chamberlain: Victorio: Apache Warrior and Chief , University of Oklahoma Press 2007, ISBN 978-0-8061-3843-5

- ↑ Edwin R. Sweeny: From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874-1886, (English) Paperback, University of Oklahoma Press (January 2012), ISBN 978-0806142722 , pages 18-20 (list of names and numbers of bands and local groups)

- ↑ Edwin R. Sweeney: Mangas Coloradas: Chief of the Chiricahua Apaches , University of Oklahoma Press 1998, ISBN 978-0-8061-3063-7

- ^ William B. Griffen: Apaches at War and Peace: The Janos Presidio 1750-1858 , University of Oklahoma Press 1998, ISBN 978-0-8061-3084-2

- ^ Trudy Griffin-Pierce: Native Peoples of the Southwest, University of New Mexico, 2000, ISBN 978-0826319081