William Henry Harrison

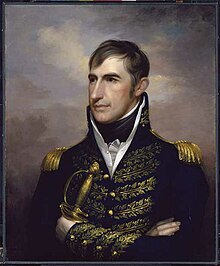

William Henry Harrison (born February 9, 1773 in Charles City County , Colony of Virginia , † April 4, 1841 in Washington, DC ) was an American major general and in 1841 the ninth President of the United States of America . He died just a month after inauguration , making him the president with the shortest term to date.

Harrison was born into a prominent Virginia family . As a younger son with little prospect of an inheritance , he was only supposed to pursue a medical career. After the death of his father with no means to study at the University of Pennsylvania , he joined the newly formed United States Army with the support of Governor Richard Henry Lee with an officer's license . Stationed in Fort Washington in the Northwest Territories against the backdrop of the Indian Wars, he soon caught the attention of General Anthony Wayne , who accepted him into the Legion of the United States and appointed him his aide-de-camp . In August 1794 he fought with him in the Battle of Fallen Timbers against a confederation of different Indian peoples .

Life

Education and training

William Henry Harrison, who was born on Berkeley Plantation in Charles City County in what was then the colony of Virginia, the youngest of seven children, came from the respected family of planters and politicians, the Harrisons . This went back to Benjamin Harrison I, who emigrated to Jamestown in 1633 . Harrison's father, plantation owner Benjamin Harrison V , was a signatory to the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and was governor of Virginia from 1781 to 1784 . Harrison V's maternal grandfather was Robert "King" Carter , one of the richest men in the Thirteen Colonies . Harrison's mother, Elizabeth Bassett, was a relative of Martha Washington . Due to the inheritance law in the colonies at the time, he was the youngest of three brothers and faced an uncertain future. Unlike the older brothers, Harrison's parents made little effort and he was homeschooled up to the age of 14. Possibly inspired by their friendship with Benjamin Rush , Harrison V and his wife planned a medical career for their youngest son, although it is unclear whether he ever felt any inclination in that direction. During the American Revolutionary War , British troops led by defector Benedict Arnold captured the family's property, stole the cattle and destroyed the interior. In addition, the widespread soil erosion on Berkeley Plantation throughout Virginia meant that crop yields steadily declined while the Harrison family continued to grow.

Unlike in the Harrison family usually the case, the parents sent him not to the prestigious College of William & Mary , but to the small and rural Hampden-Sydney College in Prince Edward County . Typical of the time, Harrison's curriculum included English grammar as well as the classics of ancient Rome such as Caesar , Sallust , Virgil and Cicero . Possibly troubled by reports that the revival movement was gaining support among students in Hampden-Sydney , his staunch Episcopalian parents sent him to Richmond . Here Harrison continued his studies with the physician Andrew Leiper and came into contact with abolitionists who organized themselves around the Quaker Robert Pleasants in the Humane Society . Soon after, his parents transferred him to the University of Pennsylvania to study medicine. When Harrison landed in Philadelphia by boat in the spring of 1791 , he learned from a messenger that his father had died. Soon after, his brothers signaled that the family was no longer able to finance his academic education. Harrison graduated and left the medical field altogether, although doctors of the time required little formal education to practice. After he unsuccessfully applied for a job in the civil service, he asked the governor of Virginia , Richard Henry Lee , counsel, and currently was in Philadelphia. When Harrison agreed to join the United States Army , Lee got him an officer license, which was approved by George Washington , who was friends with Harrison's father.

Early military career

At the time, service in the armed forces was poorly respected and poorly paid. After the victory in the War of Independence, the United States Army was involved in Indian wars, which were associated with high mortality and hardship for individual soldiers and were considered dishonorable in the higher society. Harrison began his service as a recruiting officer with the 1st Infantry Regiment in Philadelphia and was soon able to recruit almost 80 volunteers. He then moved via Pittsburgh and the Ohio River to Fort Washington , which he reached in the fall of 1791. This fort was located in what is now Cincinnati in the Northwest Territory and at that time protected one of the westernmost settlements in the United States, which consisted of no more than 30 huts. The base was almost cut off from the outside world and could only be reached via Indian trails. Shortly before Harrison's arrival in Fort Washington, the survivors of the battle of the Wabash River , which had ended in a disastrous defeat for the Americans in November 1791, had taken refuge there.

In the local officer corps , which consisted largely of veterans of the Revolutionary War, Harrison encountered major reservations as an officer with no prior military experience. Conditions in the camp were precarious: the soldiers' quarters consisted of leaky tents, weapons and ammunition were often defective, and the horses were regularly stolen by Indians . This and the monotonous routine led most of the soldiers to excessive alcohol consumption, which Harrison noted with reluctance. When the commander ordered that any soldier found drunk outside the fort be punished immediately with lashes, Harrison happily complied. In one case, angry residents of the settlement detained him for punishing a drunk in this way, and he was only released after the commander intervened. During the winter Harrison took part in marches outside the fort, one of which was used to retrieve equipment that General Arthur St. Clair and his troops had left behind after escaping from the Wabash River.

Soon Harrison was ordered to escort the commandant's family to Philadelphia. There he joined the newly established Legion of the United States and served as a lieutenant under General Anthony Wayne , a Revolutionary War celebrity. When Harrison's senior manager was transferred to another post because of an affair, Wayne promoted him to captain and appointed him his aide-de-camp , which involved a significantly higher pay . At that time his parents had passed away. He traded his Virginia inheritance for Kentucky land titles owned by the Harrison family. Surveying problems in the "Frontier" ensured that these lands, like many other Harrison investments, never made any money.

In the fall of 1793 the Legion had reached Fort Washington and marched north against the Indians. The cause of the conflict were the contracts concluded between these and white settlers. The latter assumed that if a tribe ceded land, all Indians had to leave it, even if they did not belong to this group. Harrison had to deal with complaints from such disenfranchised natives during his professional career; later he himself regularly initiated such contracts to the detriment of the Indians. With the help of the British, who were still in parts of the Northwest Territory, the Indians had defeated St. Clair, who had ignored complaints from displaced groups. With the Legion , however, they now faced a much better organized and more disciplined armed force than in 1791 in the battle of the Wabash River.

Battle of Fallen Timbers

By the summer of 1794, Wayne's 3,500-strong force had reached a position near Toledo in what is now Ohio . Due to its location in the middle of fallen trees that had felled by a tornado , the later battlefield was named Fallen Timbers ("fallen wood"). The Indian confederation , which is made up of different peoples, was surprised by this troop movement, so that many fighters were absent at this time because they were just getting provisions. In the end, Warchief Blue Jacket , a member of the Shawnee , was only able to lead 500 men into the Battle of Fallen Timbers on August 20 . Although they fought valiantly and suffered no more casualties than the Legion , they soon realized the superiority of the enemy and retreated to a nearby British fort, which, however, did not open the gates to them. Harrison rode the field of battle far and wide during the battle to maintain the lines . When things got worse, he tried to get Wayne out of the line of fire. Overall, he received great recognition from his superiors for his performance in this battle.

After the victory, the Legion burned the surrounding Indian settlements and marched south to the center of the defeated confederation, where they built a fort. In December 1794, almost all of the chiefs came to Fort Greenville to ask Wayne for a peace treaty. An exception was Tecumseh , who refused to surrender and therefore boycotted the negotiations. The negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Greenville in August 1795 , which awarded much of the Northwest Territory to the United States. Harrison, like all officers of the Battle of Fallen Timbers, was a signatory to the treaty.

Wedding and family formation

Harrison then returned to Fort Washington and soon became its commandant. Before that he was stationed in North Bend not far from Cincinnati for several months . During this time he met Anna Symmes , the 20-year-old daughter of the settler leader Colonel John Cleves Symmes . On the one hand, Anna Symmes was adapted to life in the Frontier; on the other hand, she had attended a girls' boarding school and was well-read and politically interested. She later became the first first lady to receive an education outside of the home. She and Harrison first met at their sister's home in Lexington, and later described it as love at first sight. When he asked for her hand, Symmes forbade the connection because he did not want his daughter to marry a soldier with limited financial means. However, Wayne supported the young couple.

They married on November 25, 1795, despite the refusal of the bride's father, although there are different versions of the place and circumstances of the wedding. According to one, Harrison and Anna Symmes waited until Colonel Symmes was out of town and got married in a small group at a friend's house. The other says that the wedding took place in the bride's house and her father left the ceremony prematurely. The marriage resulted in six sons and four daughters between 1796 and 1814. His son John Scott Harrison was a member of the House of Representatives from 1853 to 1857 and his son Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of America from 1889 to 1893.

It did not take long, however, and there was a reconciliation between Colonel Symmes and the bride and groom. Possibly this was promoted by Harrison quitting the military and seeking a more lucrative livelihood. To this end, his father-in-law proved useful as he was able to make contact with local soil speculators. While still in active service, he had a flour mill and sawmill built in what would later become the Indiana Territory . In addition, despite his aversion to alcohol, he acquired shares in a whiskey distillery . However, none of these companies succeeded. He was by no means alone in his generation with this unstable experience, because this phase of American history was a particularly risky one for business start- ups because of its unstable financial system . After the wedding, Harrison and his wife moved into a nearly 65-acre farm near North Bends, which he had acquired from his father-in-law along with an accompanying log cabin .

Retirement from military service

The Fort Washington headquarters was quiet. At the turn of the year 1797/1798 he left the military. Then Harrison worked as a land registry clerk and justice of the peace. As later in his life, when the post of Secretary for the Northwest Territory became vacant, he had no remorse for shamelessly exploiting his family relationships as a Harrison. In that case, he wrote to influential federalist Congressman Robert Goodloe Harper , dropping some of his family-related prominent names, and drawing attention to his tight financial situation. His scam bore fruit, and Harrison was awarded this lucrative position.

As secretary, Harrison was entrusted with the correspondence, which he dealt with conscientiously, thereby acquiring the flowery language that would later characterize his political speeches. In this function he often had to represent the Territorial Governor Arthur St. Clair . Between 1799 and 1800 Harrison represented this territory as a non-voting delegate to the United States House of Representatives in Washington. The contacts of his father-in-law in Washington proved to be helpful for Harrison, which he reluctantly used to promote him. In 1800 he was named governor of the Indiana Territory by President John Adams and therefore resigned his seat in the 6th United States Congress in May .

Governor of the Indiana Territory

As governor, Harrison resided in Vincennes , the new capital of the territory. He had Grouseland built there in the style of a plantation house, which he lived in from 1804 to 1812.

Some important conferences with leaders of the Indians of North America were held in this residence . His new role as governor was not an easy one. On the one hand, he should build friendly relationships with the Indians, win their trust and protect them against white land robbers, on the other hand, on behalf of the federal government, he should acquire as much land as possible from the Indians and make it available to the white settlers. This was an insoluble contradiction that would soon lead to new disputes with the Indians, for whom land ownership was an alien concept.

From 1802 to 1805 he enforced seven treaties with the Indians, exploiting the corruption of their leadership as well as their poverty and alcohol problems. This culminated in fraudulent land reclamation of 51 million acres in 1805 . To this end, five less important tribal chiefs of the Sauk were invited, who, under the influence of alcohol, agreed to sell large estates for a penny per 200 acres.

In 1809 Harrison negotiated the Fort Wayne Treaty with selected Native American leaders. Hostile tribes had not been invited to the conference. As a result, the United States acquired an additional 3 million acres of land. For Tecumseh, who had not attended the conference, this further loss of territory was the decisive moment to unite the tribes in the fight against the USA and to ask the United Kingdom for military support.

In 1811 the conflict escalated into open warfare and Harrison returned to service. National popularity brought him the battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811, where he was able to defeat a federation of resisting Indians (especially Shawnee ) under the leadership of Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa , the Prophet . The area between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes was finally cleared for white settlement. Harrison was then considered The General who saved the Northwest . At times he was also nicknamed "Washington of the West" or "Old Tippecanoe".

During his tenure as governor, he participated in property speculations and invested in two mills. He had a reputation as a reliable administrator and made significant contributions to improving the infrastructure in the territory.

In the British-American War of 1812 he distinguished himself against the British in the western theater of war and, after initial setbacks, defeated them in the Battle of the Thames River on October 5, 1813, in which his old adversary Tecumseh was also killed. During this war Harrison rose to the rank of general. He was Commander in Chief of the Northwest Army. Harrison retired in 1814 after falling out with Secretary of War John Armstrong . In the Indiana Territory he was subsequently temporarily represented as Territorial Governor by John Gibson and finally replaced by Thomas Posey in 1812.

Further political rise

Between 1816 and 1819 Harrison was again a member of the House of Representatives in Washington. This time he represented his new home state Ohio . For the next two years until 1821 he was a member of the Senate of that state. In 1825 he was elected to the US Senate , where he remained until 1828. That year he was appointed American Ambassador to Greater Colombia by President John Quincy Adams . He held this office until 1829. He then moved to his farm near North Bend in Ohio, where he worked as a farmer until 1836. Politically, Harrison was close to Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams and eventually became a member of the Whig Party . He advocated protective tariffs, infrastructure improvements and additional spending for the armed forces.

Presidential candidacies in 1836 and 1840

In 1836 William Harrison was nominated by the Whigs as their top candidate for the upcoming presidential election . His opponent was the former Democratic Vice President Martin Van Buren . With the nomination of a war hero, the Whigs hoped for a success similar to that achieved in 1828 by the outgoing President Andrew Jackson , who had also been elected as a war hero to the highest office of the state, in 1828 . This plan did not work in 1836 because Jackson's popularity was unbroken and he was vehemently committed to Van Buren. In addition, Hugh Lawson White , another Whigs politician, ran for election and secured almost ten percent of the vote. Van Buren won by a clear majority in the end.

Four years later, the tide had turned: The Martin Van Buren government had to grapple with the consequences of an economic crisis that broke out in 1837 . The Whigs had again nominated Harrison for their top candidate for the 1840 election, while John Tyler was slated for the office of vice president. Her campaign hit was: Tippecanoe and Tyler too . After a tough campaign, Harrison beat Van Buren. Almost 53 percent of the electorate voted for Harrison, while Van Buren won 46.8 percent. In the Electoral College the result was even clearer with 234 versus 60 votes. At the same time, the Whigs won a majority of the seats in both houses of Congress .

President for a month

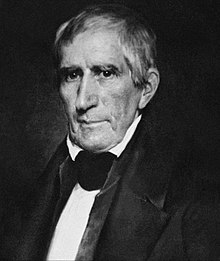

Harrison was the first American President to travel by rail to his inauguration in Washington, which he reached on February 9, 1841. He was the oldest president when he took office until Ronald Reagan . On March 4, 1841, after being sworn in, he gave the longest inaugural address of two hours, which in most places remained extremely vague. A large part of the speech was made up of his remarks on the presidential veto power , which Andrew Jackson in particular had excessively exploited. Criticism of this White House expansion had been a recurring theme in the Whigs' campaign. Harrison said the veto should only be exercised when Congress violated the US Constitution , acted too hastily and negligently, or disregarded minority rights. His cabinet included, among other things, Secretary of State Daniel Webster .

The inaugural address went down in history not only because of its length, but also because, according to conventional lore, it was causally responsible for Harrison's death four weeks later. Since the Democratic press had ridiculed him as a poor old man, Harrison did not wear an overcoat on this cold day and in freezing rain to demonstrate his vitality. This weakened him so much that he developed pneumonia. According to the biographer Collins, this is a logical explanation, but only one of many possible causes. In his short time in the capital, Harrison generally spent a lot of time outside of the city and did the shopping himself, such as for the kitchen. On the day of his illness, he had walked through the rain for a long time to personally tell a friend that he was got him a post in the diplomatic service.

Three weeks after his inauguration, he contracted pneumonia , from the consequences of which he died on April 4th at the age of 68. His presidency is the shortest in United States history, lasting one month. Harrison is also the only president who has not issued an executive order in his office . As president, he was politically insignificant due to the short term in office.

Harrison was the first President of the United States to die during his tenure and was replaced by the incumbent vice president. His death sparked a long discussion about succession in the United States. The question was whether Vice President John Tyler should only exercise the duties and powers of the President in an executive role, or whether he could be considered a full President. Tyler, against strong opposition from his opponents, opted for the second option, thereby creating a precedent that was later recognized by the constitution through the 25th Amendment .

Afterlife

personality

Harrison was considered exceptionally sociable and reconciled the refinement of his origins from a prominent planter family with the tenacity of life in the military and "Frontier". His tone was so jovial and informal that other people could quickly develop a bond with him. On the other hand, this style of communication also seduced others to consider it naive and easily manipulable.

Historical evaluation

Harrison wanted the influence that Jackson had made on the presidency back to a smaller claim to power and to restore a more harmonious relationship with Congress. On the other hand, he saw the president in his relationship with the cabinet as more than a primus inter pares , as was the case with the Republican presidents at the beginning of the century. Because of his extremely short tenure, Harrison was able to implement next to none of this.

Honors and monuments

Four counties in the United States are named after President Harrison. The series of the presidential dollar, launched in 2007, minted coins with the portraits of Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk and Zachary Taylor in 2009. His residence, Grouseland, where he lived as governor of the Indiana Territory, has been a National Historic Landmark since December 1960 .

literature

- Non-fiction

- Horst Dippel : William H. Harrison (1841): President for one month. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents: 44 historical portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama. 6th, continued and updated edition. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-58742-9 , pp. 136-138.

- Michael J. Gerhardt: The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. Oxford University Press, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-938998-8 , pp. 25-36 (= 2. William Henry Harrison ).

- Hendrik Booraem V: A Child of the Revolution: William Henry Harrison and His World, 1773-1798. Kent State University Press, Kent 2012, ISBN 978-1-60635-115-4 .

- Gail Collins : William Henry Harrison. (= The American Presidents Series. ). Times Books, New York City 2012, ISBN 978-0-8050-9118-2 .

- Robert M. Owens: Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. University Press of Oklahoma, Norman 2007, ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8 .

- Cleaves Freeman: Old Tippecanoe: William Henry Harrison and his time. C. Scribner's Sons, New York 1939, LCCN 39-032515 .

- Fiction

- James A. Huston: A novel: Tecumseh vs. William Henry Harrison . Brunswick, Lawrenceville 1987, LCCN 87-013466 .

Movies

- Life Portrait of William Henry Harrison on C-SPAN , May 10, 1999, 142 min (documentation and discussion with Doug Clanin and James Huston).

Web links

- William Henry Harrison in the nndb (English)

- William Henry Harrison in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- American President: William Harrison (1773-1841). Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia (English, editor: William Freehling)

- Harrison to the Indiana governors

- The American Presidency Project: William Henry Harrison. University of California, Santa Barbara database ofspeeches and other documents from all American presidents

- William Henry Harrison in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. Pp. 9-12.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 12f.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. Pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 15f.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 16f.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 18f.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 19f.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 20.

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 21f.

-

↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. S. 22, 24.

William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia . -

↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. Pp. 22-24.

William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia . -

↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 24f.

William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia . - ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 25.

- ↑ William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia .

- ↑ William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia .

- ↑ William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia .

- ↑ William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia .

- ↑ William Freehling: American President: William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency , Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia .

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: William Henry Harrison, ca.1850. Retrieved May 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. Pp. 115, 119-121.

-

↑ Gail Collins: William Henry Harrison. P. 21f.

Horst Dippel: William H. Harrison (1841): President for one month. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents: 44 historical portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama. 2013, pp. 136-138; here: p. 137f. - ^ Horst Dippel: William H. Harrison (1841): President for a month. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents: 44 historical portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama. 2013, pp. 136-138; here: p. 138.

- ^ Charles Curry Aiken, Joseph Nathan Kane: The American Counties: Origins of County Names, Dates of Creation, Area, and Population Data, 1950-2010 . 6th edition. Scarecrow Press, Lanham 2013, ISBN 978-0-8108-8762-6 , p. XIV .

- ↑ Steve Nolte: 2010 Coins . Frederick Fell, Hollywood 2010, ISBN 978-0-88391-174-7 , p. 137 .

- ↑ Listing of National Historic Landmarks by State: Indiana. National Park Service , accessed November 10, 2020.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Harrison, William Henry |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American politician, 9th President of the United States of America (1841) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 9, 1773 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Charles City County , Virginia Colony |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 4, 1841 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Washington, DC |