Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (* 10. August 1874 in West Branch , Cedar County , Iowa ; † 20th October 1964 in New York , New York ) was an American politician of the Republican Party and from 1929 to 1933 the 31 President of the United States .

As a mining engineer become wealthy and entrepreneur, he founded at the beginning of World War I , the Commission for Relief in Belgium and was soon afterwards by Woodrow Wilson to head the United States Food Administration appointed, bringing considerable executive powers were connected. After the war, he supported the reconstruction and food supply in Europe with the American Relief Administration . In 1921 he became Secretary of Commerce under Warren G. Harding and later Calvin Coolidge . After his victory in the 1928 presidential election, there were optimistic expectations when he took office. With the onset of the Great Depression that in America the Great Depression led and mass impoverishment, and its pitiless as perceived political countermeasures dropped its popularity rapidly, he that in the presidential election in 1932 against Franklin D. Roosevelt had no chance. He left office as one of the least popular presidents in American history. After his presidency he got involved again in food aid and was, among other things, significantly involved in the introduction of the Hoover feeding and the founding of UNICEF .

Life

Parental home and education

Herbert Hoover was born in West Branch, Iowa. His ancestors had been Quakers for six generations and had predominantly British and partly Swiss roots. By the mid-18th century, they had emigrated to the Thirteen Colonies for various reasons . The father Jessie Clark Hoover (1846-1880) came from Miami County, Ohio and had Swiss ancestors who had carried the original name Huber . The mother, nee Huldah Randall Minthorn (1848-1884) came from a Quaker settlement in the province of Canada and had English ancestors. Herbert Hoover had an older brother, Theodor, and a younger sister, Mary. When his father sold his forge and opened a shop for agricultural supplies, he was successful in business, moved his family into a larger house and was elected to the city council. When Hoover was six years old, his father died of typhus. In 1884 his mother Huldah succumbed to pneumonia, and he was subsequently taken in by various relatives. In 1885 he finally came to live with his uncle John Minthorn in Newberg , Oregon . There Hoover attended the Friends Pacific Academy , today's George Fox University , whose director and founder was his uncle. In 1888, Hoover left school to help Minthorn, who was now a real estate agent in Salem and who recognized his nephew's business acumen early on. In the evening he attended a business college where he learned mathematics.

A chance encounter with a mining engineer sparked Hoover's interest in studying at the newly formed Leland Stanford University . Although he had failed high school and failed the entrance exam, he was admitted as the youngest undergraduate for the first year of the university, subject to a successful retake test. Hoover funded his academic education with casual work. As a freshman he met the head of the Geological Institute, John Casper Branner , for whom he subsequently worked. Among other things, Hoover mapped geological outcrops and helped Branner create a relief map of Arkansas for the Chicago World's Fair , which was awarded a prize. With Waldemar Lindgren , he worked for the United States Geological Survey in the Nevada desert and the Sierra Nevada . In the later semesters he became the leader of the barbarians , who had outsiders like him as members, and competed with them in the campus elections against the elite Greek fraternities and sororities . In addition, Hoover was elected chief financial officer for the university's baseball and American football teams and was elected treasurer for his semester. In the fourth and final year of his studies, he met his future wife, the banker's daughter Lou Henry , who began her geology studies there. Since he was still largely destitute, he did not propose to her.

Engineering activity

After graduating in 1895, he worked first as a simple worker in a gold mine, later as a copyist, and then in the executive administration and inspection of new mines and mining areas in the New Mexico Territory and Colorado . In order to be able to work for the renowned London company Bewick, Moreing & Co , which was looking for a mine exploration engineer at least 35 years old in Australia, Hoover grew a beard to look older, puffed up his qualifications and established himself successfully in London Charles Algernon Moreing.

Despite the harsh climatic conditions and strenuous desert tours to remote mines, Hoover was absorbed in this new job. The Sons of Gwalia turned out to be the most productive mine recommended by Hoover . Hoover became the manager of these and seven other mines. As a supervisor, he subordinated everything to economic efficiency , rejected minimum wages and dismissed the relevant employees in the event of special salary requirements, for example for Sunday work. In the fall of 1898, Hoover, who had already risen to become a junior partner at Bewick, Moreing & Co , received the lucrative offer to oversee extensive exploration and mining work in China . Now financially secure, he married Lou Henry on February 10, 1899 in Monterey according to the Roman rite , because there was no meeting house nearby. The marriage resulted in two sons, Herbert Jr. and Allan.

During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the Hoovers in Tianjin saw the siege of their foreign enclave. Hoover stayed in the background and organized the food supply and maintenance of the barricades, which was later accused of cowardice by political opponents. After the liberation by the alliance of the United Eight States , Hoover and a Belgian business partner succeeded in ousting the local board of directors of the Chinese Engineering Company , the largest Chinese company, for $ 200,000. In 1901, after disputed negotiations, he acquired the Kaiping mines for his company , which was the largest property acquisition by foreigners in Chinese history. In the same year Hoover rose to one of the four senior partners at Bewick, Moreing & Co and resided in London until 1917.

By 1908 he increased the efficiency of the company, explored, founded and reorganized mines in 16 countries, which employed 25,000 workers. At that time, Hoover had built an excellent reputation in the mining industry around the world. Hoover also invested his private assets in mines. In 1908 he ended the partnership with Bewick, Moreing & Co and sold his partnership, making him nearly a millionaire. Against this background, the following well-known quote from Hoover should be seen: “ If a man has not made a million dollars by the time he is forty, he is not worth much ” ( William E. Leuchtenburg: Herbert Hoover . , German: “Wenn ein Man has not yet become a millionaire at forty, he is not worth much ")

Hoover's own consulting company supported economically struggling mines against later profit sharing. Lead , silver and zinc mines in Myanmar , what was then British India, proved to be particularly lucrative . With the beginning of the First World War , he withdrew from the business as a multiple millionaire.

In 1909, Hoover published a summary of his lectures at Columbia University and Stanford as a book under the title Principles of Mining , which became a standard work in the mining sciences. With Lou Henry he brought out an annotated translation of Georgius Agricola's De re metallica in 1912 . In both works, Hoover expressed more liberal social views and accepted labor protection and union rights. Politically, Hoover identified with the progressive wing of the Republicans and in 1912 supported the break-off of the Progressive Party under Theodore Roosevelt . In the same year, Hoover was elected trustee of Stanford University, where he commissioned construction projects with his own resources and significantly increased the salaries of the teaching staff. In 1919, Hoover donated the Hoover Library on War, Revolution, and Peace document archive , from which the Hoover Institution emerged .

Commission for the Belgian Aid Organization

On August 6, 1914, he founded the Committee of American Residents in London for Assistance of American Travelers with business people in the Savoy . This group raised US $ 400,000 to provide small loans to Americans fleeing Europe who were short of funds. In mid-October, Hoover received an urgent call from the American ambassador Walter Hines Page to help against an impending famine in Belgium, where the destruction of war and the sea blockade had led to a dramatic supply situation . With wealthy friends, Hoover founded the Belgian Aid Organization's commission to organize food aid . Hoover brought in a large part of his fortune and, immediately after meeting the ambassador, bought a first shipload for import via Rotterdam . The commission worked effectively in disaster relief and grew into a powerful organization that included many factories, warehouses and a fleet of canals for inland navigation. In negotiations with David Lloyd George , Raymond Poincaré and Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , Hoover was often able to reach agreements. While the British saw their blockade impaired by the aid measures, the German Empire was more compliant with the commission. The Commission for the Belgian Aid Organization cared for up to nine million people in Belgium and France and collected a total of over 900 million US dollars, of which almost 700 million were state funds. Since the 130,000 volunteers were led by 60 full-time Americans, mostly unpaid, the administrative costs were extremely low. Hoover concluded from the work of the commission that in emergencies state support is far less reliable than voluntary commitment by citizens.

United States Food Administration and American Relief Administration

Shortly after America entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Hoover Food Administrator on May 19, 1917 . Immediately thereafter, he initiated the United States Food Administration, which was under his exclusive control, as a volunteer organization with the aim of keeping domestic food prices stable and providing the Allies with food. Agricultural production was encouraged and domestic demand curbed in order to generate higher surpluses for export. Thus, under the motto Food Will Win the War, an economical use of food was propagated and, for example, meat-free Tuesdays and bread-free Wednesdays were called, while high production numbers were awarded. At this time, the expression to Hooverize became known, which referred to the voluntary but also forced rationing of food. The United States Food Administration had over 700,000 members, most of whom were members of the local elite. Hoover forced the passage of the Lever Act in August 1917, which prescribed rationing measures in restaurants and restricted alcohol production in favor of food production. He used legal coercive measures such as confiscation and state business cartels , which severely punished a violation of the fixed buyer prices. Its exceptional executive powers, which left Congress outside, met with criticism. Internationally, Hoover enjoyed a high reputation for his work. In the summer of 1918, he was received by Kings George V and Albert I , among others , to express their thanks. In the previous 12 months, the United States Food Administration had shipped $ 1.4 billion worth of food to Europe.

After the Compiegne armistice , Hoover traveled to Europe on behalf of the President. He transformed the United States Food Administration into the American Relief Administration (ARA), which, in addition to providing food, supported reconstruction. The ARA coordinated ship and train traffic, initiated the fight against typhoid and ensured the food supply for almost 400 million people in Europe. When government funds ran out in the summer of 1919, Hoover converted the ARA into a private donation organization. Hoover partly used the high American food surpluses as a means of political pressure, for example when Joseph August of Austria was deposed as imperial administrator in Hungary .

Soon Hoover was traded as a possible candidate for the upcoming presidential election , whereupon Hoover took a contradicting position. Since he was an opponent of the emerging social Darwinism, was on friendly terms with the union leader Samuel Gompers and rejected the rampant First Red Fear , the progressive party wing of the Republicans and the liberal press such as The New Republic and The Nation in particular sympathized with Hoover. Despite its Republican character, many Democrats saw Hoover as a possible candidate for their party, including Edward Mandell House and Franklin D. Roosevelt . On March 30, 1920, he confessed to the Republicans and expressed his readiness for a presidential candidacy against the foreseeable hopeless Democrats. Hoover's programmatic demands on the party, his difficult position as a former food administrator with the farmers as well as his long stay abroad and the cooperation with the internationalist Wilson proved to be a hindrance. At the California Primaries , he competed against Senator Hiram Johnson , who received nearly twice as many votes as Hoover. In the end, Warren G. Harding became a representative of the Republican Conservative presidential candidate.

Minister of Commerce

Even before the Republicans won the presidential election of 1920 , which resulted in a clear majority against a continuation of Wilson's policies and international engagement, Harding offered Hoover the post of trade or interior minister despite criticism from within the party . After initial hesitation, just two weeks before the President's inauguration , Hoover decided on the Commerce Department and asked for it to be given more authority. He was to keep this ministry until August 21, 1928 under the subsequent presidency of Calvin Coolidge .

Hoover significantly expanded the responsibilities and thus the importance of the ministry at the expense of other departments, so three new departments for construction, radio and aviation were created. A key position was taken by the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce under Julius Klein , whose budget Hoover increased sixfold. Staff in this department were posted to major cities around the world to promote vigorous American trade and business opportunities overseas, and market events were recorded in regular public reports such as the Survey of Current Business as accurately as they were in Europe only three decades later . He particularly promoted aviation, introduced flight licenses and regular safety inspections and prescribed lighting and radio beacons for all runways . This commitment led to the capital's first airfield being named Hoover Field in 1926 . He countered the flood of radio stations, which had grown from 2 to over 300 within a year, with licensing, the exclusion of amateurs and the allocation of transmission frequencies, but left it with a purely private broadcasting market. In addition to government regulation of new industries such as aviation and radio, Hoover introduced the standardization of components, devices and tools across more than a hundred different industries through the Bureau of Standards . To develop better standards in construction, but also to deregulate existing regulations, Hoover founded the American Construction Council , chaired by Franklin D. Roosevelt . When the latter asked Hoover to put more pressure on the industry to reach agreements, the trade minister refused and the panel failed. As Secretary of Commerce, he warned several times that a speculative bubble could develop , asked Coolidge to take action against insider trading , and advocated an increase in the Federal Reserve System's interest rate to prevent the bull market from falling. Even so, he was later generally held responsible for the Great Depression and for decades presented by the Democrats as the specter that the nation would expect in the event of a Republican president.

As Minister of Commerce, he also positioned himself politically in competition with Foreign Secretary Charles Evans Hughes and Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon, and occasionally with President. He criticized the military intervention in Nicaragua and the currency policy towards Mexico and advocated strict immigration rules for Japanese and Latin Americans, also based on ethnic prejudice. On the fundamental question of whether American investments should be protected militarily worldwide if necessary, he was in opposition to Hughes, Mellon and Harding. Instead of intervening, he saw the solution in avoiding such economic risks at all, which is why he was also an opponent of arms loans abroad. Although Hoover did not reject his own protective tariffs such as that of Fordney - McCumber from 1922 on European imports, he fought against protective tariffs and subsidies from other countries, including waging a price war with the Colonial Office under Winston Churchill over the world market price of rubber . He enforced famine relief for the Soviet Union from 1921 to 1923, although he fought its state recognition all his life. The American Relief Administration , which Hoover headed, served 15 million people there with a few American volunteers.

Although actually under the responsibility of the Ministry of the Interior, Hoover developed conservation initiatives, including those for the preservation of Niagara Falls and Chesapeake Bay . He led particularly bitter arguments with Agriculture Secretary Henry Cantwell Wallace , who could see no understanding of the economic plight of the farmers at Hoover, despite his support for the Agricultural Credits Act , which encouraged lending to agricultural banks and cooperatives. Mainly for reasons of efficiency, Hoover saw the establishment of agricultural cooperatives in addition to modernization and mechanization as a way out of the farmers' crisis. The promotion of such cooperatives for production and marketing became the basis of the 1925 Cooperative Marketing Act. Hoover vigorously opposed the legislative proposal by Representative Gilbert N. Haugen and Senator Charles L. McNary , which provided for the state to set minimum prices for domestic agricultural products and was particularly pushed by Wallace. A passing of the McNary-Haugen Bill later failed due to two vetoes by President Calvin Coolidge .

Hoover also acted very intensively in the area of responsibility of the Minister of Labor James J. Davis . When there was a strike in the coal mining industry in 1922, Harding appointed him arbitrator. Hoover initially enjoyed sympathy among the unions because he advocated adequate wages and representation of workers in committees to strengthen domestic consumption and was an opponent of union busting . However, he did not differentiate between free trade unions and dependent company trade unions, so that he did not oppose when the entrepreneurs increasingly leveraged the closed shop principle when they were founded. When the unemployment rate had risen to over 4 million in August 1921, he persuaded Harding to call a conference under his chairmanship. Although ultimately only the barriers to public works at the local level were lowered and with no evidence, Hoover later attributed the end of the 1921-23 recession primarily to this conference. In the steel mills, with the support of the president, Hoover was able to break resistance from US Steel and other companies and enforce an end to the 84-hour week. In 1924, in cooperation with the trade unionist John L. Lewis , he forced an agreement in the coal industry, but without reacting later to the breach of the conditions by the employers. He came into intermittent conflict with Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty , who wanted to investigate the promotion of trade associations by Hoover under the Antitrust Act . His extraordinary commitment outside of his department led to the public gibberish that Hoover was not only Minister of Commerce but also Secretary of State in all other ministries.

In 1922 Hoover published the monograph American Individualism , in which he analytically derived his essential conviction of individualism as the superior value system compared to others, such as European capitalism and communism, from philosophical works and his own experiences abroad. Accordingly, America's private entrepreneurship was the best way to achieve social justice and equal opportunities for individuals. Hoover was not a supporter of a laissez-faire policy , but saw a means to the common good in coordinating state action with private-sector interests, as is done, for example, in business associations and supervisory authorities. American Individualism was largely positively reviewed and rated as a significant contribution to social theory. Although Hoover criticized socialism most sharply in this work, because it sees people as purely altruistically motivated, he raised himself with the progressive views expressed in it from the then prevailing reactionary mood and increased his reputation.

As a minister from the progressive party wing of the Republicans, Hoover was considered a possible candidate for the vice presidency alongside Coolidge in the 1924 presidential election . For this position, however, Charles Gates Dawes was selected by the delegates of the Republican National Convention . Coolidge had previously entrusted Hoover to lead the California primary campaign against his challenger, Senator Hiram Johnson. In the Cabinet , Hoover retained his ministerial post after Coolidge was elected.

Hoover peaked in popularity when President Coolidge appointed him crisis manager for the 1927 Mississippi flood. Hoover set up his headquarters in Memphis for the next few months and traveled incessantly on the Mississippi between Cairo and New Orleans to appeal to the local population to support the people who had become homeless. He managed to collect 17 million US dollars in donations and to organize 600 ships and 150 tent cities for emergency aid. As was typical for him, Hoover, who was more prominent than the President at the time, emphasized the success of the local improvisation he had initiated and omitted that a good third of the financial and other resources from authorities such as the Public Health Service , the Ministry of Agriculture and the National Guard .

1928 presidential election

When President Coolidge announced in 1927 that he would not run for re-election, Hoover was considered the most promising Republican candidate for the 1928 presidential election . The candidacy did not go smoothly, because on the one hand there were doubts as to whether he had been a resident of the United States for 14 years, as required by the electoral law, and on the other hand, the conservative party wing added his directive policy as a food administrator. In the end, he won the primaries in all states except West Virginia, Ohio and Indiana. Hoover was nominated in the first ballot at the Republican National Convention in Kansas City, Missouri in June 1928 and chose as running mate for the defeated rival Senator Charles Curtis from Kansas , who later became the first and so far only Vice President with Native American parents. A few days after the convention, Hoover resigned as minister in order to concentrate fully on the election campaign. The speech for the formal acceptance of the nomination, which the candidate had traditionally held from the front of his private house, was given by Hoover thanks to the efforts of Ray Lyman Wilbur in front of 70,000 spectators at Stanford Stadium . On this appearance, which opened his presidential campaign, Hoover identified with Harding and Coolidge, promised to continue their politics and predicted that the day when the end of poverty was in sight in America would soon come. The election manifesto included lower taxes, protective tariffs, rejection of agricultural subsidies and upholding prohibition . Hoover benefited from his biography and reputation for being an efficient technocrat and world-renowned benefactor . In addition, the economic success of the Roaring Twenties was attributed to the Republicans Harding and Coolidge, whom he had served as ministers. Hoover was considered a weak speaker and shied away from being present in the election campaign, which in the end was limited to six appearances, including in his birthplace, Boston and New York City. He also held seven radio addresses to the nation in which he his Democratic rival, the governor of New York , Al Smith mentioned even once. Hoover mainly organized and administered the election campaign and spent days meticulously preparing for his few speeches. The Republicans made the film Master of Emergencies , which highlighted Hoover's strengths as an efficient administrator and crisis manager. The political indifference and reluctance of the technocratic Hoover was portrayed in the election campaign as a virtue heralding a new age in which technical experts rule the state and no longer professional politicians. In order to make the cool and rigid effect of his personality more sympathetic, which was identified as his main weakness, the campaign managers sent several thousand photos signed by Hoover of him smiling with his favorite dog King Tut , a German shepherd dog .

Especially in rural America there was sometimes violent resentment against the Democrat Smith, as he was a Catholic and an opponent of Prohibition. The Ku Klux Klan issued pamphlets against Smith and organized rallies against him. The fact that Smith was part of the Tammany Hall rope team was also detrimental to him. To get the vote of the white voters in the southern states, Hoover denied his opposition to the Jim Crow laws and avoided a conviction of the Ku Klux Klan. With a popular vote of more than 58 percent, Hoover won the election, taking from his competitor New York his own state and five more in the democratic Solid South .

Presidency

Hoover was sworn in as the 31st President of the United States by Chief Justice William Howard Taft on the afternoon of March 4, 1929 . To date, this will be the last inauguration of the President of the United States in which a previous president sworn in for one of his successors. With his inaugural address, which was followed by almost 100,000 viewers in front of the Capitol and 63 million listeners on the radio, Hoover met the optimistic expectations associated with him as a successful technocrat and the spirit of the Roaring Twenties . Hoover's extreme confidence and his conviction of the superiority of American individualism resulted in the sentence “ In no nation are the fruits of accomplishment more secure ” ( Herbert Hoover, Inaugural Adress (1929) , German: “In no nation are the fruits of progress safer ”) As a problem he addressed the increase in crime around the 18th Amendment to the alcohol prohibition , for which he did not blame individual or state failure, but an inefficient organization of the legal system.

He appointed Andrew W. Mellon (Finance) and James J. Davis (Labor) to his cabinet , two ministers with whom he had already served in Coolidge's cabinet . Above all, the appointment of Mellon was supposed to please the old party guards. Hoover offered Senator Charles L. McNary the post of Secretary of Agriculture in a gesture to the wing of the party that worked to protect farmers' incomes . However, this refused. In his place Arthur M. Hyde took over this office, in whose area of responsibility the president himself took political initiative.

Secretary of State Henry Stimson , Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur , who was a close friend of Hoover , Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams and Justice Minister William D. Mitchell proved to be powerful ministers in the following years . As an advisor on economic issues, Hoover mostly relied on the Treasury Undersecretary, Ogden L. Mills , and thus bypassed Mellon. His White House staff was small for the time and very loyal to Hoover. Some employees, such as Lawrence Richey, George Akerson and French Strother, had already helped him in the 1928 primary. Walter Newton acted as Hoover's private secretary .

The beginning of the presidential reign turned out to be positive. When he was inaugurated, the stock market prices rose, he had majorities in the Senate and House of Representatives, and the press had been very favorable to him since his time as minister, when he regularly invited reporters to his office for open discussions. One of his first acts as president was to relax the press litigation laws for journalists, which had been tightened under Coolidge. Hoover's initial initiatives in Congress, where he could count on the support of Speaker Nicholas Longworth , concerned customs policy and agricultural crisis relief. He also supported the establishment of the National Institutes of Health , which took place in 1930 under the Ransdell Act , and the creation of the Veterans Administration in the same year. Hoover tried to initiate legislative programs primarily through 64 conferences and commissions, which were often privately financed.

On the evening of December 24, 1929, a fire severely damaged the West Wing of the White House. Hoover has since used offices in the main building or nearby ministries.

Domestic politics

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

The question of whether free trade or protectionism should dominate American foreign trade policy has long been debated. Hoover was not a supporter of high protective tariffs , but believed that domestic agriculture in particular had to be protected from cheap products and low wages abroad, especially since his economic model of prosperity included high wages (“high-wage economy”). He proposed to Congress in April 1929, with the support of the progressive wing of Republicans under William Borah, a tariff law, which was passed by the House of Representatives on May 28, 1929 as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act . A controversial American public debate arose over the law; Finding a majority in the Senate proved difficult, especially since Hoover remained passive and made no attempt to negotiate a compromise or to exert pressure on Congress in the context of political clientelism . At the end of the legislative process in Congress, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act did not contain any of the proposals that Hoover had tabled in the House of Representatives in April 1929 with the support of progressive Republicans. In June 1930, despite his opposition, Hoover finally signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which was considerably tightened by the Senate in terms of protectionism, which put a heavy burden on his relationship with the progressive wing of the party and is considered the greatest political defeat of the first two years in office.

In addition, over 1,000 neoclassical economists from 179 universities called on the President to veto. Instead, however, the legislative package was even expanded and raised the tariffs beyond the agricultural sector for industrial products to an all-time high, while agricultural export subsidies were abandoned. The independent commission of experts requested by Hoover, which was supposed to influence the customs tariffs, was included in the law, but in practice did not come into effect. As a result, 25 trading partners of the United States responded with countermeasures and increased import duties on American products. In this context, some states tightened control of exchange rates and devalued their own currency in order to generate trade surpluses. Within two years of the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, American exports fell by nearly two thirds.

Agricultural policy

American farmers were in a bad economic situation in the 1920s. New technologies have increased the yields, but prices have fallen due to overproduction and strong foreign competition. Republican Senator Charles L. McNary and Chairman of the House Agriculture Committee, Gilbert N. Haugen , had proposed bills to subsidize agriculture, but the McNary – Haugen Farm Relief Bill had failed four times by Coolidge's rejection by 1928. Instead, he opted for the ideas of his then ministers Hoover and William Marion Jardine , which envisaged electrification, better seeds and more efficient cultivation and sales methods, including through economic cooperatives. As president, Hoover presented a law based essentially on Jardine to the establishment of a Federal Farm Board , which was supposed to support the formation of agricultural cooperatives with 500 million dollars in order to achieve a price stabilization. Resistance in Congress led to a compromise solution, the Agricultural Marketing Act , signed by Hoover on June 15th. Agricultural products could now be marketed through national agencies such as the Farmers National Grain Corporation . These organizations should also buy up large overproduction in order to keep prices stable. In addition, loans were provided for establishing and stabilizing agricultural cooperatives. The Federal Farm Board occupied Hoover with industrialists, such as the CEO of International Harvester , who were perceived by many farmers as their exploiters. He also gave instructions to keep the financial scope for aid as narrow as possible. When the agencies began their work in October 1929, the global economic crisis began a short time later. The Federal Farm Board ended up doing nothing but futile market stabilization and was shut down in June 1931 after losing $ 345 million and Hover's refusal to enforce production controls.

National parks

Hoover named the noted conservationist Horace M. Albright chairman of the National Park Service . During his presidency, the protection area increased by 3 million acres, or 40 percent. With the Great Smoky Mountains and the Everglades , the first national parks were created in Eastern America. The Commission on the Conservation and Administration of the Public Domain , created by Hoover in October 1929, intended to make non-reserved public land and land reclamation the responsibility of the states, thus subordinating nature conservation to potentially other interests at the local level. This plan failed because of the resistance of the western states, which refused to take over the administration of the large pastures in their areas and continued to see Washington in this duty.

Minority policy

At the age of six, Hoover had lived with an uncle in the Osage County Indian Reservation , Oklahoma, for six months . He mentions in his memoir that he attended school and Sunday school on the reservation during this period. The uncle and various other relatives worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs . Hoover is the only US president to have lived on a reservation.

Hoover appointed Quakers Charles Rhoads and Henry Scattergood, who were civil rights activists in the Indian Rights Association , to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs. According to his memoirs, the Quakers' commitment to the Indian population was the decisive factor. Both defined a new Indian policy . Until then, dealing with the Indians was characterized by segregation into reservations on the one hand, and the pursuit of complete assimilation into American society on the other, as Hoover wrote in his memoir. Hoover criticized the intention of the previous policy to "civilize" the Indians against their will. He also rejected the Dawes Act dividing the reservation land into parcels . His plan, which was based on the Meriam Report published in 1928 on the situation in the Indian reservations, provided for the Indians to achieve economic independence and pride and respect for their own culture. For this purpose, they proposed an Indian Arts and Crafts Board within the Ministry of the Interior , which should guarantee better marketing of Indian handicrafts and their copyright protection. Because Hoover preferred private financing and occupation of the Indian Cooperative Marketing Board of Directors instead, it was not set up until 1934 under Hoover's successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt . Investing in education and health should also improve the opportunity for Indians to live integrated American citizenship. Food aid has tripled and modern hospitals with better trained staff have been built. Though Hoover's goal remained the assimilation of the Indians, his government laid the foundation for a new Indian policy that would be followed for the next forty years.

In 1931, Hoover vetoed a compensation bill that promised the Choctaw , Cheyenne , Chickasaw and Arapaho financial compensation for their lands confiscated by the American state. He justified the veto with the increase in the value of the land over the past fifty years and the need to keep contracts. But he advocated an increase in spending on Indian reservations by $ 3 million.

With regard to the Afro-American civil rights movement , he privately supported the Urban League with donations. As president, he sponsored Howard University and won Julius Rosenwald's foundation to fund the Conference on the Economic Status of the Negro . Lou Hoover aroused particular attention and racist protests from southern politicians when she welcomed the wife of African-American representative Oscar Stanton De Priest for tea in the White House. Hoover's policies in the southern states as a whole were disappointing for African Americans and resulted in their traditional loyalty to Republicans as Abraham Lincoln's party beginning to break. He refused to condemn lynching of African Americans and insisted that they should continue to entrust their welfare to the local white elite.

Judiciary

At the White House Conference on Health and the Protection of Children in 1930, a 19 article (non-legally binding) charter on children's rights , the Child's Bill of Rights , was adopted by Hoover . The results of the many studies that the conference, which consisted of several thousand delegates, brought together and published in 35 volumes, shaped social work in the field of child rearing and health protection over the next few decades. The conference recommended, among other things, a ban on child labor and the creation of state welfare in this area. Hoover glossed over the Commission's statement that 10 million children lived in poverty or were physically disabled by stating that the majority of 35 million children grew up in healthy conditions.

In response to the Valentine's Day massacre , Hoover founded the 11-person National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement , chaired by George W. Wickersham . This examined the legal system, focusing on the effects of Prohibition and adequate reforms. The results of the commission on the spread of police violence and corruption attracted particular national attention. However, their recommendation in the final report of January 1931 to maintain prohibition, although only two of the eleven members believed it was effective, was generally perceived as a laughing stock. This deliberately misrepresentation of the results in the eyes of the public by the president, who had been committed to the abstinence movement since his election campaign in 1928 , raised doubts about his credibility. Hoover appointed William Fielding Ogburn to lead the Committee on Recent Social Trends , which included social scientists such as Charles Edward Merriam , Wesley Clair Mitchell and Howard Washington Odum. Several variables of society, such as population composition and diet, were recorded statistically and the 1600-page report was finally published in 1933. All studies and conferences had in common that they did not envisage an active role for the state in solving the problems, which is why the report had little political impact. At the end of his tenure, Hoover signed the Norris - LaGuardia Act into force. This restricted yellow dog contracts (employment contracts that prohibit membership in trade unions) and the possibility of ending strikes by court order.

On May 14th and 27th, 1930, Hoover ratified two laws designed to greatly expand the federal prison system to relieve overcrowded local and state prisons. To this end, he set up a separate agency in the Justice Department, the Federal Bureau of Prisons . Hoover named Sanford Bates its first director . The construction of the necessary new prisons as well as the improvement of the supplies for the inmates and the training of the guards was budgeted at 5 billion US dollars.

After the death of Edward Sanford, a member of the United States Supreme Court , Hoover had a duty to appoint a successor. Despite the onset of the Great Depression , this personnel decision tied a great deal of the President's attention in the first half of 1930. On March 21, 1930, Hoover decided in favor of John Johnston Parker , who, however, due to his positive judgments in the Court of Appeal on Yellow-dog contracts , made considerable decisions Resistance from the American Federation of Labor met. In addition, Parker was accused of a statement from his gubernatorial election campaign in North Carolina in 1920 , in which he had spoken out against the active participation of African Americans in politics. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NACCP) accused him of being biased against blacks. The progressive Republicans, led by William Borah, prevented his appointment in the Senate on May 7 with a narrow majority of 41 to 39. This was the first time in over 30 years that a president failed with his candidate in such a nomination. To the delight of the progressive wing of the party, Hoover was able to get Benjamin N. Cardozo to succeed Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. at the Supreme Court in 1932 . In addition to anti-Semitic voices, there had been regional concerns about these personnel, as three of the chief judges were from New York State. With Charles Evans Hughes and Owen Roberts , Hoover successfully nominated two other justices to the Supreme Court during his tenure.

Hoover Dam and other construction projects

In 1922, Hoover had headed the Colorado River Commission as Minister, which dealt with the distribution of water rights between the adjoining states in order to build a reservoir . On November 24, 1922, he was able to reach an agreement between seven of the eight participating states. In June 1929, Hoover passed the Boulder Canyon Project Act in Congress , which, in addition to supplying water in southern California, aimed to control floods in the Imperial Valley and generate 3 million kilowatt hours of electricity . Despite the preference in this law for municipalities and other public bodies in the distribution of the generated electricity, private companies were in fact preferred under Hoover's presidency. As president, he provided the funds to build Boulder Dam on July 3, 1930 . The state contract for the construction agreed with a company from San Francisco was the most expensive in American history at just under $ 49 million. When Interior Minister Wilbur named it Hoover Dam on September 17, 1930 at the opening ceremony of a rail link between Las Vegas and the dam under construction , this was received with a critical eye. On the one hand, such a designation was unusual for presidents still in office, on the other hand, with the onset of the global economic crisis, Hoover had become extremely unpopular in parts of the press. Under Hoover's successor Roosevelt, Interior Minister Harold L. Ickes decreed on May 8, 1933 the removal of this honor and the introduction of Boulder Dam as the official name for the building. It was not until 1947 that Congress decided to rename it Hoover Dam .

On May 1, 1931, Hoover opened the Empire State Building in New York, which was then the tallest building in the world . To do this, he switched on the skyscraper's lights from Washington. As a national event, it received wide coverage on the radio.

The Muscle Shoals Bill , already approved by Congress , which was introduced by Senator George W. Norris and provided for the state commissioning of a dam near Muscle Shoals , was vetoed by Hoover in 1931. For ideological reasons he refused to compete with the private sector with a state-owned company. Under his successor, the project was resumed and formed the basis of the Tennessee Valley Authority .

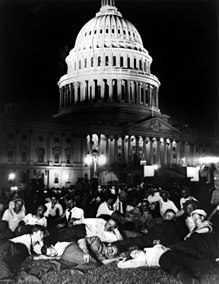

Bonus Army

While the Senate on June 17, 1932 , debated a bill that went back to Wright Patman and had already passed in the House of Representatives, which provided for an immediate payment of earned bonuses to veterans of the First World War , and rejected it by a clear majority in the evening, the Capitol was approved by 6,000 members of the Bonus Army besieged. During the day, an additional 13,000 Bonus Army members flocked to Capitol Hill . A total of 43,000 veterans and their families from a nearby slum - the so-called Hoovervilles , who grew up everywhere during the Great Depression - stayed there in vacant buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue or makeshift camps waiting for Hoover's decision. When police and protesters clashed on July 28, in which two veterans were killed, Hoover ordered the military to evacuate the premises. The commanding General Douglas MacArthur disregarded the President's instructions to the contrary and had the Bonus Army driven out of their slum quarters on the Anacostia River with six tanks and cavalry and infantry units with mounted bayonets around midnight , which burned down for unknown reasons. No other event during his presidency damaged Hoover's reputation like this and cemented the public belief that he was a cold and heartless person.

Foreign policy

Good Neighbor Policy

Shortly after the presidential election, Hoover toured ten states in Latin America and announced that the United States would be politically and militarily restrained in the region, as well as an effort to be good neighbors. Hoover had the Clark Memorandum published in 1930 , which found the incompatibility of the Roosevelt-Corollary and Monroe Doctrine , thereby calling into question the legality of interventionist measures. With the exception of a threat to intervene against the Dominican Republic , Hoover abstained from all interference, even when anti-American regimes came to power during the 20 revolts in Latin America during his term in office . He ended the US military intervention in Nicaragua after the election of Juan Bautista Sacasa . In a contract he assured Haiti that the American occupation would end on January 1, 1935. Hoover thus laid the foundations for the later Good Neighbor Policy of his successor towards Latin America.

At a conference in Washington in January 1929, Hoover brokered a compromise between Chile and Peru on the open questions of the Treaty of Ancón . In addition, negotiation protocols for the course of arbitration proceedings and a general agreement on arbitration were adopted there. These agreements became the central foundations for interstate conflicts on the American continent, but proved ineffective in the years to come.

Hoover moratorium

Since the fall of 1930, Hoover blamed the international economic situation, especially in Europe, for the depression in America. The German embassy in Washington reported a rumor to Berlin that he wanted to end the global economic crisis with a spectacular initiative in order to go down in history as the “great president”. The German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning then suggested to Ambassador Frederic M. Sackett that America should convene a world economic conference on disarmament, political debt and international economic development. Finance Minister Mellon already discussed with the former German Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht the possibility of deferring payments both for the German reparation obligations and for the inter-allied war debts that the European victorious powers had to repay America. But Hoover refused: he had always resisted the European stance, which saw a direct connection between the German reparation obligations and the inter-allied war debts.

This attitude began to change in the spring of 1931, when, after the collapse of the renowned Austrian Creditanstalt Bankverein, more and more short-term personal loans were withdrawn from Germany and Brüning indicated in June that payment of his reparation obligations would soon cease as part of an emergency ordinance that provided for tough austerity measures . If Germany declared a payment moratorium, which it was entitled to under the provisions of the Young Plan , it threatened to spark an international debate about the inter-allied war debts. Washington absolutely wanted to prevent this. In the Hoover administration, Ogden Mills in particular spoke out in favor of proposing a moratorium on reparations and war debts. Also from the banks of Wall Street , the president was pushed in this direction, because a German moratorium explanation for his political debts threatened a switch tower on private banks trigger, which would have in a general insolvency of the country may end. The American banks, which had lent loans worth over three billion Reichsmarks to German firms, hoped that a temporary waiver of repayment of Germany's political debts would secure their loans. The British government under Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald also pressed. Hoover hesitated for a long time because a one-year waiver of war debt reduced government revenues by about $ 250 million. He also feared resistance from the isolationist chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, William Borah. When a German moratorium appeared imminent on June 18, 1931, Hoover decided to act. Instead of the originally planned two years, the moratorium was to last only one year. He informed the British government and instructed Ambassador Sackett to ask in Berlin for a telegram from Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , in which he in turn asked for American help. Due to indiscretions in the press, Hoover could not wait for this call for help and published his proposal on June 20, 1931.

This explanation came like a bang. In Germany it was widely cheered, only the National Socialists were angry: “The Hoover offer [...] will postpone our victory for about 4 months. It sucks! ”Noted Joseph Goebbels in his diary on June 24, 1931. Public opinion and the government in France reacted all the more indignantly, since they, as the largest reparations creditor, had not been consulted. Paris saw this as a clear affront. In view of the worldwide approval of Hoover's plan, it did not appear to be refusable. The government of the liberal-conservative French Prime Minister Pierre Laval therefore tied its approval to making the Hoover moratorium compatible with the legal provisions of the Young Plan . This was achieved in complicated negotiations that dragged on until July 8, 1931. In this loss of time, Hoover's proposal lost much of its psychological impact. The loan withdrawals from Germany grew into a devastating banking crisis , on July 13, 1931, Germany declared its insolvency for all foreign debts. That was what Hoover had tried to avoid with his initiative.

Disarmament conferences

Hoover, who as a Quaker had a more pacifist sentiment than most other presidents in American history, persistently sought international disarmament agreements , with the backing of British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald . For him, morality was the means of choice for creating peace; not military. Domestically, in the summer of 1929 he had already created a commission to downsize the army and put armaments projects for the US Navy on hold. In 1930 Secretary of State Stimson attended the London Naval Conference with a delegation of distinguished Republicans and Democrats to negotiate arms control measures in the Navy. There Stimson could agree with the United Kingdom and Japan, but not with France and Italy, restrictions on the number and size of warships. The Senate approved this agreement in July 1930.

At the Geneva Disarmament Conference in 1932, the President's delegation made unrealistic demands for the abolition of all submarines, fighter planes and tanks and a significant reduction in all other armaments expenditure. Without empathy for its history and threats, Hoover scolded France for its high defense budget. By the end of his tenure, the conference had no results.

Hoover-Stimson Doctrine

During the Manchurian crisis in September 1931, Hoover reacted cautiously, especially since as an engineer in Tianjin he had developed prejudices against China, rather sympathized with the industrialized nation of Japan and was fully engaged in domestic politics with the global economic crisis. In order not to be drawn into this military conflict, Hoover spoke out against a boycott of Japan and fended off attempts by the League of Nations to bring Washington into position against Tokyo . In January 1932 the Hoover-Stimson Doctrine was officially declared by the Secretary of State. Accordingly, America did not recognize any territorial changes in this conflict that ran counter to the provisions of the Briand-Kellogg Pact signed by Japan in 1928 .

Great Depression

The expectations of Hoover, the first president to be born west of the Mississippi , were very high. He was seen by the public as a successful technocrat who was supposed to run the economy efficiently and make the entire country prosperous. Prosperity ("prosperity") was therefore also the key concept of his speech when he took office. The in October 1929 with the Black Thursday incipient world economic crisis certain Hoovers remaining presidential and his initially wide popularity was reversed into its opposite. He had not seen the crisis coming and just before the crash he said optimistically “ We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land ” ( Howard Zinn: A People's History of the United States . , German: "We in America are closer to the ultimate triumph over poverty than any other country in history"). In the further course of the event, Hoover avoided the term crisis and always spoke of a depression , which permanently damaged his reputation.

This statement was refuted by the effects of the Great Depression , which rapidly escalated from October 1929. In the first public reactions, Hoover continued to be optimistic about the economic situation, but worried that the recession was beginning and worked with his government on countermeasures. The proposals of his advisors included tax cuts, a loosening of the interest rate policy of the Federal Reserve and an expansion of public works, which the president also urged the states and municipalities to do. In keeping with his style, Hoover relied on cooperation, voluntary commitments, scientific expertise and statistical data collection, as well as limited government measures. He commissioned the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Labor to precisely record and document the development of the economic parameters. In November 1929 he held several conferences with unions, companies and government officials and obtained promises that there would be no more strikes for wage increases or layoffs. Henry Ford promised wage increases and further investment after one of these conferences that month. For more than a year, a sizable portion of the pledges, including price stabilization by the Federal Farm Board , a rate cut by the Federal Reserve, and public investment of $ 150 million by Congress, were to be met by the organizations involved, and most rapidly Decline in investment but nothing changed. Many companies did not cut wages, but cut production and cut salaries. The resulting collapse in private demand led, in a vicious circle, to the economy in turn further reducing production and wage costs. A depression set in and deepened, which among other things led to the fact that, despite the agreements and commitments of the conference, the number of unemployed rose by one million in the ten days before Christmas 1929 alone. At that time, at the suggestion of Hoover, the Chamber of Commerce , chaired by Julius H. Barnes , invited business associations to the National Business Survey Conference , which was supposed to discover and remove key business obstacles. It was based on voluntary work and was able to fall back on the expertise of 170 participating organizations. The National Business Survey Conference made according to historian Robert S. McElvaine nothing more than to spread optimism and turned out to be such a failure that it had already dissolved in 1931 and accompanied by Hoover, who initially with enthusiasm, later in his, detailed Memoir was not mentioned.

In March 1930, contrary to popular belief, the Ministry of Labor and Commerce informed the President that the crisis had bottomed out. On this basis, Hoover turned down further government-funded programs, corrected the unemployment figure reported by the United States Census Bureau from over three to under two million, and publicly announced on May 1, 1930 that a rapid recovery was in sight if the efforts were continued. In the same month the economic situation turned for the worse again. With this initiative as well, Hoover founded the President's Emergency Committee on Employment (PECE) in the fall of 1930 , and appointed his friend Colonel Arthur Woods to chair it . The PECE coordinated unemployment assistance from private charities. The historian Robert S. McElvaine rates the optimistic naming as typical of Hoover's presidential commissions: The incomplete selection and emphasis on ideas and information as well as the lack of efforts to collect reliable unemployment statistics, let alone to finance local support, created a positive picture of the situation Value was more anecdotal than exact. Significantly for Hoover's basic conviction, the PECE also relied on voluntary cooperation and cooperation with the state, to which Hoover later commented as follows: “ Personal responsibility of men to their neighbors is the soul of genuine good will; it is the essential foundation of modern society ”(, German: “The personal responsibility of people for their neighbors is the soul of natural good will; it is the essential basis of modern society ")

The depression deepened further in the course of 1930; so the decreased gross capital formation by 35 percent. and the construction industry shrank by 26 percent. A total of more than 1,300 banks went bankrupt in 1930, and in the last two months alone there were more than 600. There were bank rushes . In December, the private Bank of United States announced its bankruptcy, which was the largest bank failure in history. With the Federal Reserve declining to bail out, insecure investors tried to sell their stocks, which further destabilized prices. Unlike the 1907 panic , the big private banks did not capitalize on the market because they relied on the Federal Reserve as a lender.

In 1931, Hoover appealed to the public not to lose optimism. At the beginning of the year he said: “ What this country needs is a good big laugh. There seems to be a condition of hysteria. If someone could get off a good joke every ten days, I think our troubles would be over ”( Hoover (1931) after: Robert S. McElvaine The Great Depression: America 1929–1941 . , German:“ What this country needs is a good big laugh. Hysteria seems to prevail. If someone lets out a good joke every ten days, I think our worries would be over. ") In February 1931, a few months after his party's great losses in the 1930 Congress elections , who thus had a majority of the Democrats for the first time since 1919, Hoover signed a bill from the Democratic Senator Robert F. Wagner . The Wagner-Graham Stabilization Act provided for the planning of public employment programs during periods of economic recession. The Federal Employment Stabilization Board thus created remained, according to the will of the presidential administration, an insignificant authority dealing with statistical analysis that had achieved next to nothing until its dissolution in June 1933. Hoover blocked another law to strengthen the largely ineffective United States Employment Service in early 1931 with a pocket veto . In August 1931, Hoover transformed the PECE into the President's Organization for Unemployment Relief (POUR), to whose head he appointed Walter S. Gifford, the head of AT&T . The POUR, which relied on public fundraising and similar marketing, turned out to be just as powerless as the PECE. The National Credit Corporation (NCC), founded in October 1931, was Hoover's last attempt to rely on volunteer work and agreements. The NCC aimed to get banks to federate regionally based on the Federal Reserve Districts and had $ 1 billion in loans to lend to these organizations. After two months, this project failed because the banks were not prepared to organize themselves in associations and to grant loans to one another. Additionally, the NCC's loans were limited and did not exceed $ 10 million in the two months they were in existence. In the fall of 1931, large industries like Ford and General Motors began to distance themselves from their November 1929 pledges not to cut wages. The reason for this decision was Hoover's refusal to guarantee the companies minimum profits in the face of deflation and constant nominal wages.

In the State of the Union on 8 December 1931 Hoover announced next austerity and fiscal consolidation reviving founded during World War I the War Finance Corporation of. This independent authority , renamed the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) from January 1932 , was endowed with 500 million US dollars and mainly provided banks, railroad companies and insurance companies with loans against adequate collateral. During Hoover's tenure, the RFC's capital was increased to 2 billion. The RFC was the most important initiative founded by Hoover to fight the Great Depression and was continued under his successor with higher loan amounts. The RFC became a symbol of the negative public perception of the president, as it provided little direct aid for the unemployed or small businesses. With regard to bank runs , the RFC was unsuccessful, and in 1933 over 4,000 banks failed. A step in the direction of what would later become the New Deal's job creation efforts was the $ 700 million Hoover invested in 1931 to create jobs in the public sector.

The Great Depression deepened further in 1931; With rising unemployment figures, gross investments fell by 35 percent over the course of the year and the construction industry shrank by a further 29 percent, while over 2,000 banks went bankrupt. The impoverishment was now visible in the public space. More than a million homeless citizens lived in empty freight cars known as Hoover sleepers or in slums known as Hoovervilles . The President himself was always more disreputable than Ebenezer Scrooge .

The 1932 budget deficit was 60 percent, the largest in peacetime in American history, while unemployment rose to 12 million and one in four farmers had lost their land to creditors since 1929. Republicans and Democrats then agreed on the Revenue Act of 1932, which provided for tax increases and surcharges to balance the budget. Hoover, who personally was probably willing to accept deficits during times of depression, realized that his position was politically unsustainable and agreed. Against the sales tax provided for in the law , which would have hit the entire population, Congress received an unprecedented flood of letters of protest that had an effect. In the polls, progressive Republicans and Democrats united against their party leaders, so that by the end of the Revenue Act, real estate, surcharge , and income taxes included increases in real estate, surcharges , and income taxes for the high income , but no sales tax . Although it affected only 15 percent of all American households, it represented the largest tax hike in American history in peacetime. In the same year, at the suggestion of Hover, Congress passed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act . The Federal Home Loan Banks (FHL banks) created by him were intended to assist homeowners with mortgages . To this end, the FHL banks lent capital primarily to the saving and loan associations (S & Ls) and also to insurance companies . The FHL banks did not issue direct mortgage loans, but financed the market through rediscounting . However, the measure came too late and the loans were linked to too high conditions, so that the FHL system could no longer work effectively, which was particularly bad for the S & Ls. The momentum of successful public protest against the introduction of sales taxes made it inevitable for Republicans and Democrats to advocate direct poor and unemployment benefits. Hoover vetoed a first legislative proposal of this direction, which was passed by a large majority in Congress, which he justified as follows: “ Never before has so dangerous a suggestion been seriously made to our Country ” ( Hoover (1932) according to: Robert S. McElvaine The Great Depression: America 1929–1941 . , German: “Never before has such a dangerous proposal been submitted to our country”) An amended draft of the Emergency Relief and Construction Act , which still contradicted Hoover's fundamental convictions, signed the President in July 1932. Since the Hoover supporters in the decisive positions of this aid program were just as hostile to state welfare, the lending was very economical and according to petty, sometimes humiliating procedures, to which both the inquiring citizens and the states or their governors undergo had. Of the 322 million US dollars made available by January 1933, only six million had been approved. The fact that the RFC, previously created by Hoover in December, turned out to be more generous in providing financial support to banks, was gratefully accepted as an issue by the Democrats in the 1932 presidential election. In fiscal 1932, Hoover approved an additional $ 750 million in public sector investment, primarily for construction projects such as ports, docks , flood control, shipping lanes, military installations, and the continuation of the Hoover Dam. Nevertheless, the situation worsened over the course of the year. In October 1932, shortly before the presidential election, Hoover announced a banking moratorium for Nevada , which was followed in February 1933 by the collapse of the financial system in Michigan. The cities of Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland were hit hardest by bank runs .

1932 presidential election

Failing to lead the United States out of the greatest national crisis since the Civil War, and unable to find a public gesture of compassion for its increasing impoverishment, Hoover was accused of ruthlessness and harshness and, through the left-liberal magazine The Nation, even "cold-blooded murder" . In the 1932 presidential election, Hoover had no chance against the Democratic candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt , who promised new hope for the population with the New Deal . The press, which initially sympathized with Hoover, had increasingly turned away from him since the end of 1929, not least because he left most of their inquiries for interviews unanswered and insisted on reading them before going to press and only then approving them. By 1932 this developed into a relationship of mutual almost hostile rejection. In the end, with a popular vote of almost 40 percent , Hoover lost 57 percent to Roosevelts and won only six states in New England . He left office as the least popular president since Rutherford B. Hayes 52 years earlier.

At a meeting with his elected successor Roosevelt on November 22, 1932 in the White House, Hoover urged him to maintain the gold standard and to induce the United Kingdom to return to this monetary system through appropriate concessions. He also urged Roosevelt to take a clear position on the war debt issue, although his administration had failed to do so even with regard to the results of the Lausanne Conference . Hoover did not get any binding commitments from Roosevelt, not even in the weeks that followed when they continued their negotiations. Hoover's term of office ended on March 4, 1933.

Post presidency time

After his election defeat and the assumption of office of his successor, Hoover bitterly withdrew from the public. Wrongly responsible by the general public for the onset of the Great Depression and despised as a lackey on Wall Street, even his own party kept his distance from him. Hoover fought back the allegations by publishing more than two dozen books over the next few years. In it he sharply attacked the policy of the New Deal, calling it fascist and socialist, among other things . He accused Roosevelt of striving for a central administration economy and suspected him of pursuing totalitarian goals. Although he continued to advocate strict libertarianism , on the other hand, he presented himself as the spiritual father of the New Deal measures, which were successful. In the presidential election of 1936 he supported the Republican Alf Landon after his own hopes for a nomination clearly failed.

In 1938, Hoover toured Europe, where, unlike at home, he was very popular. In Belgium the masses celebrated him on his journey through the country; King Leopold III. distinguished him, and the Université Lille Nord de France awarded Hoover his first honorary doctorate , which was followed by a dozen more. In the German Reich, Hoover only gave in to pressure from the American ambassador Hugh Robert Wilson and accepted an invitation from Adolf Hitler . At one point in their conversation, according to a report, he asked Hitler to be silent and to sit down again when he was standing up to give a tirade of several minutes about Jews. Hoover later visited Hermann Göring in Carinhall . His attitude towards Jews was ambivalent; On the one hand, Hoover was shocked by the persecution of the Jews in the Third Reich , on the other hand, in his opinion, they had too much influence on American foreign policy . In July 1939, Hoover ruled out that Berlin had any plans for war, and even after the attack on Poland he considered a German attack on France to be an absurd assumption. Hoover refused to allow America to join the fighting.

At the Republican nomination convention for the 1940 presidential election in the United States , Hoover put himself into the game, although his supporters advised against it, given the internal party approval rating of two percent, according to the Gallup poll . He could hardly win delegates for himself and in the end the political career changer Wendell Willkie , a liberal Republican, challenged Roosevelt, who later won the election. Even his campaign support for Wilkie was undesirable in some states and was grossly rejected in Connecticut, for example. Hoover remained a relentless opponent of the re-elected Roosevelt, dismissing the Four Freedoms as useless without a fifth freedom, which would concern free enterprise and the right to accumulate property. Although Roosevelt was advised after America's entry into World War II to seek Hoover's assistance because of his services as head of the United States Food Administration, in the face of Hoover's unforgiving stance, he decided against it. Hoover's wife Lou died in January 1944, prompting him to leave her home in California and reside at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City . In the party, Hoover remained isolated and was ignored at Willkie's funeral in October 1944 by Thomas E. Dewey , the Republican candidate for the 1944 presidential election . During the war he was involved in food aid and collected large amounts of donations that benefited the people of Finland and Poland .

After the Second World War, Hoover drafted a much-noticed proposal that led to the establishment of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). On March 1, 1946, Roosevelt's successor, Harry S. Truman , contacted Hoover and entrusted him with an overseas mission to the war-torn nations in Europe and Asia. In the next three months he visited 38 countries to assess the local famine and met 36 Prime Ministers and Pope Pius XII. and Mahatma Gandhi . Back in America he described his impressions in a radio address that is considered his best speech. In his report on post-war Germany published in March 1947, Hoover recommended that the president stop the dismantling of the industrial plants and stated that Germany could be militarily weakened without hindering supplies to its population. The Hoovers report was controversial and received particularly positive feedback from John R. Steelman , the White House chief of staff . In 1947, the Republican-controlled 80th Congress appointed him chairman of the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government , the so-called Hoover Commission , which proposed measures to lower bureaucratic and administrative hurdles and strengthen executive power. Hoover campaigned for the introduction of school feeding , the so-called Hoover feeding , in the bizone . This benefited over six million Germans who received one warm meal a day. Apart from this cooperation with Truman, he represented opposing positions in foreign policy. Opposed to America's intervention in the Korean War, Hoover opposed the Bretton Woods system and NATO , which he believed to be a grave mistake to create. In his opinion, all communist states should also be excluded from the United Nations . Despite these differences, Hoover's relationship with Truman was much better than that of his successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower . This set up a second, more conservative Hoover Commission in 1953 , which again headed Hoover.

As memories of the Great Depression faded, Hoover's reputation as a statesman rose . At a banquet in honor of Hoover in 1957, John F. Kennedy gave the laudatory speech ; his book The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson became a bestseller the following year . He worked to the last on a biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, but it was so one-sided that it was never published in order not to damage his reputation. On Hoover's 90th birthday, 16 states declared this day Herbert Hoover Day . Hoover died of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in New York City on October 20, 1964, and was buried on October 25 in his birthplace, West Branch. The funeral procession from Cedar Rapids to the place of his burial was accompanied by almost 80,000 people, at the request of the family, an honorary salute was waived.

Afterlife

Historical evaluation and personality

In the thirty years after his presidency, despite his worldwide popularity as a benefactor, the judgment on Hoover was shaped by the derogatory and gloomy stereotypes that arose about him during the Great Depression . The Hoovervilles named after him are symbolic of this. Only after the opening of the presidential library in 1966 did historical studies examine his personality and motives for action in more detail and in depth. Hoover is still considered a weak president, although the causes of the Great Depression went back to his predecessors. In general, he has the stereotype of having been a president of laissez-faire , which historical facts do not confirm. During the Great Depression, he pursued a more active policy than any other American president who had previously faced a depression. According to Jürgen Heideking , recent research has made it clear that Hoover was not the weak president he was oversubscribed as for a long time, but was able to provide some innovative impulses. While history used to draw a rigid line between Hoover's informal economic regulation and Roosevelt's compulsory regulation, this distinction is less strictly observed today.

Although Herbert Hoover rarely attended church services as an adult, married according to the Roman rite and did not abstain from alcohol, he was shaped throughout his life by the Quaker theology conveyed in the family primarily through the pious mother and her appreciation of the individual responsibility of the individual, the importance of freedom, charity as well conscientious work. His trust in the neighborhood community as the best means of providing support to those in need also emerged from this experience. At a young age he therefore donated a large part of his fortune to friends, relatives and to poor students or lecturers, later he very successfully initiated charitable voluntary organizations at his own expense. Since he made most of the donations, including his entire salary as president, anonymously, the scope of his charity is still unknown. His biographer George H. Nash took the view that no one in history had succeeded in saving more people from death than Hoover. Hoover's philosophical belief in the importance of the individual is reflected in the 1922 monograph American Individualism .

As the biggest supporter of the Efficiency Movement and Taylorism of all presidents , who had already campaigned as a student with a corresponding program, Hoover believed in being able to avoid crises and achieve higher growth rates with a better organized economy . Even in the midst of the Great Depression during the 1932 election campaign, Hoover at the Republican National Convention campaigned primarily for scientific management as a path to new progress. Further elements of the content of this movement included greater efficiency , the elimination of waste and the cooperation of business leaders, state representatives and social scientists in order to coordinate planning. To promote the latter aspect, Hoover supported the establishment of business associations . He rejected the theory of a free market economy without state regulation. His social ideas were based on Thorstein Veblen . Like him, Hoover saw the ingenuity of the ever increasing number of engineers as the main driver of industrial progress. Although his experience taught him better, he considered voluntary organization and initiative to be more appropriate means of crisis management than state intervention, which corrupts those receiving aid. This so-called associationalism , pious belief in the effectiveness of associations, cooperatives and committees compared to direct aid was later criticized many times, including by Joan Hoff Wilson, a biographer who campaigned for the rehabilitation of Hoover. According to the biographer Jeansonne, with careful expansion of state competencies, Hoover showed moderate behavior on this issue, so that he was attacked from both sides. Although Hoover promoted conferences as a means of avoiding purely top-down processes , he often used them simply to get his own way by determining who attended, chairing, and drafting final reports and recommendations for action on his own. As a matter of principle, he rejected direct state intervention in the economy as bureaucratic, although he himself was supposed to create many authorities in his political career. “ Even if governmental conduct of business could give us more efficiency instead of less efficiency, the fundamental objection to it would remain unaltered and unabated ”( Herbert Hoover (1928). , German:“ Even if state management were to give us more instead of less efficiency, the fundamental opposition would remain unchanged and undiminished ”)