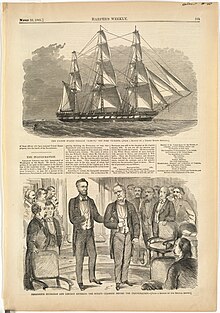

James Buchanan

James Buchanan [ bjuːˈkænən ] (born April 23, 1791 in Peters Township , Franklin County , Pennsylvania , † June 1, 1868 in Lancaster , Pennsylvania) was an American politician and from 1857 to 1861 the 15th President of the United States .

Buchanan came from a relatively well-off family descended from immigrant Ulster Scots . After studying at Dickinson College, he learned the legal profession in Lancaster , which brought him considerable wealth. In 1814 he entered the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and later represented his state in both houses of Congress . Shaped by the Jacksonian Democracy program , he was a loyal Democrat all his life . He served as Secretary of State under President James K. Polk ; under the presidentsAndrew Jackson and Franklin Pierce he was envoy to the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, respectively . After several unsuccessful attempts at the presidential primaries , he won in 1856 at the Democratic nomination party congress and in the following presidential election .

As an opponent of abolitionism and sympathizers of the southern states he took before his inauguration decisive influence on the verdict of the Supreme Court in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford . He not only demonstrated his slavery-friendly attitude, but also violated the principle of the separation of powers . His bias for the South was reflected in the composition of the cabinet and the spoil system . Because of his opposition to Stephen Douglas , Buchanan became increasingly alienated from large parts of the party. According to the Jacksonian Democracy , he did little to counter the economic crisis of 1857 , while he made greater use of his powers in the conflict with the Mormons under Brigham Young and led to a negotiated solution to the Utah War . In the violent constitutional conflict of Bleeding Kansas , in which it was about slavery in the territories , Buchanan stood behind the antiabolitionist Lecompton government and influenced Congress accordingly. This resulted in bribery that was later investigated by the Covode Commission. For Buchanan, the congressional committee had no legal consequences, but his reputation suffered considerable damage. By the 1860 presidential election , Buchanan, who did not run again, had so divided the Democrats that the Northern and Southern wings could not agree on a common candidate and the Republican Abraham Lincoln made the running.

In terms of foreign policy, Buchanan pursued an expansionist line in the spirit of the Manifest Destiny , with the purchase of Cuba being his main unattained goal. Buchanan was more successful in pacifying the pig conflict with Great Britain, creating a basis for negotiations for the later purchase of Alaska from Russia and the admission of the United States as a party to the Treaty of Tianjin with China . Historically, Buchanan is one of the biggest hardliners among the presidents of America in terms of foreign policy and is considered the most vehement expansionist before Theodore Roosevelt .

In the secession crisis that immediately followed Lincoln's election, Buchanan remained largely passive. He accepted that South Carolina and other southern states left the Union, confiscated federal property and in February 1861, before Lincoln took office, formed the Confederate States of America . Although he called the secession illegal in December 1860, he was of the opinion that neither the President nor Congress had the power to prevent the individual states from doing so by force. It was not until the Fort Sumter crisis , which South Carolina demanded that the conflict between Buchanan and the breakaway states broke out. Since cabinet members loyal to the Union urged him to end his policy of appeasement towards the south, he gave the green light to strengthen the fort in January 1861. After the handover to Lincoln, Buchanan withdrew from politics. In 1866 he published an autobiography in which he defended his presidency against sometimes sharp attacks, and died two years later.

After Buchanan had been outlined as a peacemaker by American historiography, which was then friendly to the southern states, until the Second World War , he has since been widely regarded as one of the weakest presidents and his cabinet as one of the most corrupt in American history. In contrast, some historians argue that research on Buchanan is too inconsistent to call him the worst president in American history. To date, he is the only president in United States history to remain unmarried. There is still speculation about Buchanan's possible homosexuality .

Life

Education and training

James Buchanan was born in April 1791 in a simple log cabin in Stony Batter, now Peters Township , in the Allegheny Mountains of southern Pennsylvania . He was the second of eleven children with six sisters and four brothers and the eldest son of James Buchanan Sr. (1761-1821) and his wife Elizabeth Speer (1767-1833). His father was an Irish American who immigrated from County Donegal in 1783 . He came from the Buchanan clan , whose members had since the early 18th century because of famine and religious persecution as Presbyterians from the Scottish Highlands increasingly emigrated to Ireland and later America and are known as Ulster Scots . Educated and ambitious, he first lived with a wealthy uncle in York after his arrival in the young United States , before buying a trading post in Stony Batter in 1787, which was at the crossroads of five transport routes in what was then the Frontier . In 1788 he returned to York for a short time to marry Elizabeth Speer. She also had Scottish - Irish roots and was Presbyterian. In his unfinished autobiography , Buchanan mainly credited his mother with his early education, while the father shaped his character more. His mother talked to him about political affairs when he was a child, quoting John Milton and William Shakespeare .

In 1791 the family moved to a larger farm in the area of Mercersburg and three years later, thanks to the social advancement of their father, to a two-story brick house in the village itself. Buchanan Sen. was a merchant here and soon became the wealthiest citizen of the city. James first attended a private school in Mercersburg, the Old Stone Academy. The curriculum customary at the time included classic educational elements such as Latin , Greek and mathematics. From 1807 Buchanan attended Dickinson College in Carlisle thanks to paternal support . In 1808 he was expelled from college for improper conduct; with fellow students he had attracted negative attention through drinking bouts in local taverns and the associated nocturnal disturbances and acts of vandalism. Buchanan later stated in his memoir that he took part in these activities in order to be considered brave and witty in his environment. With the intervention of the Presbyterian school principal and the college's board of directors, he was re-admitted to class and graduated the following year with good, but not the outstanding grades he believed he deserved. He then went to Lancaster , the then capital of Pennsylvania, for two and a half years as a lawyer with the famous James Hopkins. Since law courses were only offered at three universities at the time , legal studies usually took the form of professional training. Following the fashion of the time, Buchanan's education, which lasted until 1812, dealt with the discussion of legal authorities such as William Blackstone, in addition to the United States Code and the United States Constitution . Self-disciplined, he acquired the systematic line of thought characteristic of common law and the orientation towards precedents that would later shape his political principles and activities. As a learner, he became a common person in the city center who used self-talk as a learning method while walking.

Attorney and the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

After his oral exams and admission to the bar, he stayed in Lancaster even when Harrisburg became the new capital of Pennsylvania in 1812 . Buchanan quickly established himself among the city's legal officials as the coming man. Despite this, his personality, mainly due to the admonishing advice of his father, remained shaped by caution and restraint and lacked the forward-looking optimism that characterizes many political leaders. Although he was seen as a skilled conversationalist, he lacked any sense of humor. As an attorney, he was a generalist and took on all sorts of cases throughout the southern Pennsylvania judicial district. Even as a beginner he tried to find prominent cases in order to increase his awareness and price, whereby the style of his negotiation was described as persistent and straightforward but unimaginative. His professional success quickly made him a wealthy man and brought him the acquaintance of important state politicians . The last annual income before his election to the United States Congress in 1821 was around 175,000 US dollars in today's currency .

At that time he became a member of a Masonic Lodge and later its Master of the Chair . He also served as chairman of the local branch of the Federalist Lancasters Party . Like his father, he supported her political program that provided federal funding for construction projects and import duties, and the re-establishment of a central bank after the First Bank of the United States license expired in 1811. Accordingly, he was opposed to President James Madison , of the Democratic-Republicans belonged, and his handling of the British-American War . While he did not serve in a militia himself during the War of 1812, during the British occupation he joined a group of young men who stole horses for the United States Army in the Baltimore area . In 1814 he was elected to the Federalists in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, where he was the youngest MP, and held that seat until 1816. This election victory was followed by ten more in the next few years, until he was rejected as senator by the State Legislature in 1833 . When opponents within the Democratic Party later accused him of his federalist orientation from those early years, he asserted that he had simply followed his father to the federalists. In 1815, he defended District Judge Walter Franklin in impeachment proceedings before the Pennsylvania Senate . Franklin had ruled in favor of the latter in a classic conflict between individual states and the federal government . Since at that time the boundary between abuse of office worthy of sanctions and a wrong legal decision depended on the preferences of the ruling parties and the popularity of the judge's verdict, such impeachments occurred more frequently. Buchanan was able to convince the senators with the argument that only judicial crimes and clear violations of the law were grounds for impeachment.

Typically, Buchanan reined in his ambitions and, through his father's pessimistic tendency, saw any progress as possibly the last step in his career. Since the sessions in the Pennsylvania General Assembly were only three months, he continued the legal profession at a profit by charging higher fees and having more solvent clientele due to his political activities. At that time he was in love with Ann Coleman in Lancaster. Coleman's father was like Buchanan Sr. from County Donegal, Ireland and was a Presbyterian. Raised wealth as an iron manufacturer, he was considered one of the wealthiest men in Pennsylvania. By the summer of 1819, Buchanan and Coleman had become engaged in the informal fashion customary at the time, but ended their relationship that fall. Obviously, from Coleman's perspective, the break was driven by neglect by Buchanan, who paid more attention to his career than hers. She accused him of only being interested in her money. On the part of Buchanan, the end of the relationship may be due to his possible homosexuality , which is still discussed today. He went to Dauphin County for business immediately after the break , while Coleman, under pressure from her mother, went to Philadelphia to recover. Here she inexplicably died of "hysterical convulsions" shortly after her arrival at the age of only 23. Her father forbade Buchanan from attending the funeral service and funeral. Afterwards Buchanan started the legend that he remained unmarried out of devotion to his one and only love, who died early. In 1833 and in his fifties, he spoke of marriage plans, but they did not lead to anything and were possibly only due to his ambitions for a seat in the federal Senate or the White House . In the latter case, the aspirant was 19-year-old Anna Payne, the niece of former first lady Dolley Madison . So to this day he is the only president in American history who has remained unmarried for his life. He also stands out from his era, as only three percent of all American men did not marry until the Civil War .

In the United States House of Representatives (1820–1831)

In the 1820 congressional elections , Buchanan ran for a seat in the House of Representatives . Shortly after his election victory, the father died in a carriage accident. Buchanan belonged to the faction of the "Republican Federalists", which indicated with their mixed party program the transition from the competition of federalists and Democratic-Republicans characterized first party system in the Era of Good Feelings ("Era of good feelings"). During this era, the Democratic Republicans became the only influential party. Buchanan's federalist beliefs hadn't been very strong anyway. As a member of parliament in Harrisburg, a colleague had urged him to change parties when he opposed a federalist nativist bill that banned naturalized citizens from electoral positions in the state. During the presidency of James Monroe , Buchanan tended more and more to the positions of the emerging modern democrats around Andrew Jackson . After Jackson lost the presidential election in 1824 , he joined his faction. But Buchanan had only disdain for Buchanan because he misinterpreted his efforts to mediate between the Clay and Jackson camps as treason before the decisive vote on the presidency in the House of Representatives. Until the end of his life he felt committed to the goals and contents of the Jacksonian Democracy , which triggered a reorganization of the political situation in the following years. Their core messages were to strengthen popular sovereignty through the expansion of the right to vote, increase in power for the federal states and the limitation of federal powers . Only on the question of import duties did he deviate from the party line out of consideration for the Pennsylvania electorate and advocate raising them. By the 1830s, Buchanan had developed into a distinct advocate of States' Rights , oriented towards the 10th Amendment to the Constitution , without questioning the American Union. Like most Democrats, Buchanan believed that the United States was simply the sum of its states.

Buchanan represented the United States through the 21st Congress . His first speech to the plenum in the 1821-22 session was about the financing of the United States Army . The dry rhetoric anticipated his later contributions to the debate, which were characterized by careful preparation, evidence and counter-evidence as well as sentimental debauchery. From the beginning he sought to get close to members of the southern congress, while he believed those from New England were radicals. Important friendships with southerners were those with William Lowndes , Philip Pendleton Barbour, and John Randolph of Roanoke . The short distance to his constituency gave him easy access to his electorate, allowing Jackson, Pennsylvania, to forge a democratic coalition of former federal farmers in the north, artisans in Philadelphia and Ulster Scottish Americans in the west. In the presidential election in 1828 he secured this state, while in the parallel congressional elections, the "Jacksonian Democrats", which appeared as an independent party for the first time after the National Republican Party split off, achieved an easy victory.

During his ten years as a member of Congress, his talent and influence were rated as mediocre. He stood behind leaders like Henry Clay , John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster . On the other hand, Buchanan did not belong to the faction of the inconspicuous and incompetent MPs with alcohol problems, who at the time populated the Capitol in large numbers . He received the greatest attention during an impeachment trial in which he appeared as a prosecutor for Federal District Judge James H. Peck. This had arrested a lawyer in St. Louis who had criticized his decisions. In the House of Representatives, the process had only been initiated when Buchanan became chairman of the United States House Committee on the Judiciary ("Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives"). At the Senate hearing, Buchanan alleged that Peck had violated the United States Constitution and federal law with criminal intent. He was to be condemned, otherwise one bowed to his judicial arbitrariness. The Senate ultimately did not follow Buchanan's plea and approved Peck with a majority of one vote. He achieved his greatest political success as a representative at the end of his term of office. In this case, the members of the Judiciary Committee decided, without his consent, to partially revoke the Judicial Act of 1789. As a result, the Supreme Court would have lost the right to an initial hearing and jurisdiction as a federal appellate body at state level; it would only have come into play through the courts of the federal district and federal appeals courts . Although an outspoken supporter of the States' Rights , Buchanan saw the authority of this institution and thus the constitution as a whole significantly damaged. He spoke accordingly to the House of Representatives, which ultimately rejected the Judicial Committee's recommendation.

When his congressional membership began, the political landscape was still marked by the debate surrounding the recently passed Missouri Compromise , which banned slavery north of 36 ° 30 ′, thus balancing the number of free and slave states at twelve. Even 30 years later, Buchanan still hoped that this settlement would adequately settle the slave question, although this conflict remained virulent throughout his career and dominated public discourse. In 1830, for example, he wandered off about an embassy to Panama on a foreign policy question and spoke about slavery . He argued that the peculiar institution ("special institution"), as it was euphemistically called in the southern states, was a political and moral evil, but there was no remedy for it. Buchanan pictured the specter that a liberation of the slaves would inevitably lead to a "massacre of the noble-minded and chivalrous male class of the south". In 1831 he declined a nomination for the 22nd Congress of the United States through its counties from the Dauphin , Lebanon and Lancaster existing constituency from. He continued to have political ambitions, and some Pennsylvania Democrats put him up as a candidate for vice presidency in the 1832 election . Jackson chose Martin Van Buren as his running mate and in late 1831 offered Buchanan the diplomatic mission to the Russian Empire .

Envoy to the Russian Empire (1832–1833)

Reluctantly, Buchanan accepted the post. On the one hand, distant St. Petersburg was a kind of political exile, which was the intention of Jackson, who considered Buchanan an "incapable busybody" and untrustworthy. On the other hand, he did not speak the French language used in diplomacy at the time and was reluctant to let his legal practice rest. He served a total of 18 months as the American envoy to the Russian Empire . The main focus of his activity was to conclude a trade and a shipping agreement with Russia. While Buchanan was successful in the former, negotiating an agreement on free trade with Foreign Minister Karl Robert von Nesselrode proved difficult. During his stay in St. Peterburg he learned French, was received at an audience by Tsar Nicholas I and realized how long diplomatic processes were. Although Buchanan thoroughly enjoyed social life in the capital's high society , as a staunch democrat he was bothered by the autocratic regime, which manifested itself in political censorship and an omnipresent secret police . To make matters worse, his mother and a brother had died while he was away. All in all, he was happy when he returned to America at the end of 1833.

Senator (1834-1845)

Back in the United States, he lost the election in the State Legislature to Senator for the full six-year term in the 23rd Congress , but he was appointed to succeed Senator William Wilkins , who in turn succeeded him in St. Petersburg. Buchanan remained a member of the Senate until March 1845 and was confirmed in office twice. He gained in reputation and together with the fact that no American president had come from Pennsylvania so far, he saw himself increasingly entitled to the highest aspirations. To do this, he had to unite the Pennsylvania Democrats at their party convention - the State Convention - so that they elected him as a candidate for the National Convention . Because open ambitions for the White House were considered unseemly at this time, Buchanan told friends that the senatorial honor was enough for him. As a Senator, he strictly adhered to the requirements of the State Legislature of Pennsylvania and voted contrary to his own speeches in Congress a few times.

From 1834 he moved into a pension community with Senator William R. King from Alabama , which led to speculation about a possible homosexual relationship between the two. From these shared apartments, often unmarried congressmen, friendships often developed that went beyond political alliances. Over the years the pension community has included Edward Lucas , Bedford Brown , Robert C. Nicholas, and John Pendleton King . This group of staunch Jackson supporters achieved considerable political influence in the 1830s and controlled two important Senate committees. The historian Balcerski considers it possible that Buchanan's partisanship for the southern states was shaped in this pension community.

As a loyal supporter of Andrew Jackson's program, he opposed the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States , which ended in 1836. Accordingly, he supported Van Buren's plan to keep the public funds decentralized and voted against when Congress rebuked Jackson for his monetary policy . Despite his pro-Southern stance, he turned against Senator Calhoun when the latter proposed a law that banned Congress from accepting abolitionist petitions. Buchanan saw this violate the republican principle of popular sovereignty. By the 1840s, his position on the slave question had become rigid. It saw slavery as a national weakness, not for humanitarian reasons, but because it posed a potential threat to the American Union. Buchanan also regarded it as an internal affair of the southern states, as it was subject to the jurisdiction of the individual states on the one hand and the family life of the planters on the other . Correspondingly, he viewed the abolitionists with hostility, and he predicted that their movement would soon end.

Buchanan established himself alongside Clay, Webster, Calhoun and Thomas Hart Benton in the front row of Senators. He turned down President Van Buren's offer to become United States Attorney General . Reputation, diligence and loyalty to the party raised him to prestigious senate committees such as the one for justice and the one for foreign relations , which he chaired from 1836 to 1841. It was above all this position that contributed to his national fame and made his most important political successes possible. In addition, he headed a Senate committee on the slave question and the prohibition of the slave trade in Washington in the 1830s. Buchanan's guiding principles were States' Rights and Manifest Destiny , which proclaimed expansion as the destination of the United States and which had been pushed westward by all presidents up to that point . In his day, all Democrats and most of the Whigs were representatives of Manifest Destiny , with Buchanan being one of its first and most ardent advocates and later turning it into political action as Secretary of State and President. His reasons for the continental expansion of the United States, which encroached on Mexico and Central America in the 1840s , are textbook-like in nature. In 1841, for example, he was only one of the few senators who voted against the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with the United Kingdom because he called for the entire Aroostook Valley for the United States. While the supporters of Manifest Destiny from the slave states spoke exclusively for the annexation of Texas and parts of Mexico and Central America, those from the northern states only advocated expansion towards Canada and the Oregon Country . Buchanan, on the other hand, advocated territorial expansion of the United States in both directions.

In the Oregon Boundary Dispute he adopted the maximum demand of 54 ° 40 ′ as the northern limit and in his last lengthy speech before the Senate in February 1845 he advocated the annexation of the Republic of Texas , asserting three reasons: one deserved the independent Texas part of the "glorious confederacy" to his American states, on the other hand, a large part could be moved slavery there and the risk of slave revolts in the cotton belt ( " cotton belt are reduced"). Buchanan also feared that the Republic of Texas would offer Great Britain an occasion for military intervention if independence continued. He also strove to divide Texas into five individual states, so that the Senate could maintain the balance between newly added free and slave states. Within the Democrats, he was the most extreme representative of Manifest Destiny , which was particularly popular in what was then the west and south of the United States and less in the Central Atlantic states and New England. In addition to his ambitions for the White House and his sympathy for the political mood in the southern states, Buchanan's maximum territorial demands were based on his experiences as envoy in St. Petersburg. Here he came into contact with the opportunism of British colonialism , which is why he saw the danger of intervention by the United Kingdom in Oregon, Texas or Mexico in the event of more moderate territorial claims.

Foreign Minister (1845–1849)

In the presidential primary election of 1844, Buchanan hoped for a nomination again, this time being more aggressive than in 1836 and 1840. He wrote to the Democratic party leaders of all states and, if Van Buren waived, offered himself as a candidate. Nevertheless, he refrained from a public election campaign, which was gradually gaining legitimacy at the time. To his disappointment, he was not successful this time either. Instead, the Democratic National Convention nominated James K. Polk , who won the subsequent presidential election . Following the conviction at the time, the new President appointed Buchanan as foreign minister in his cabinet in order to eliminate him as a party competitor, but also to compensate him for his support in the election campaign. Although this ministry was considered the most important department and gave him the opportunity to implement his expansionist goals, he asked Polk in December 1845 for his replacement and for a nomination for a vacant seat in the Supreme Court. Concerned that he might not be confirmed as a federal judge by the Senate, he withdrew this request in February 1846. In June of the same year he changed his mind again, but after a few weeks finally withdrew from this idea, not least because a top federal judge had never become president. By December 1847, Buchanan's ambitions had come back to life, and in light of the upcoming presidential election , he was inviting party leaders and other politically influential people to dinners in the capital, which he hosted on a regular basis.

During his tenure as Secretary of State, the United States under Polk recorded its historically largest area growth of 67%, which subsequently gave rise to 22 new states. Most of the territorial gains were due to the conquests in the Mexican-American War and the shares received in the Oregon Country. Buchanan, who had aimed for an even greater expansion, and the President both pursued the same strategic goals according to the Manifest Destiny , but more often came into conflict over the tactical means to be used and other details. The Secretary of State did not think highly of Polk's expertise and understanding of geography. In the Oregon Boundary Dispute with Great Britain, they did not switch their positions for the only time: While Buchanan initially spoke out in favor of the 49th parallel as the border of the Oregon Territory with British North America , Polk called for a more northerly border line. When the Northern Democrats rallied in the 1844 election campaign for the popular slogan Fifty-Four Forty or Fight ("54 ° 40 'or war"), Buchanan adopted this position as a question of national honor, which if necessary by military means to be clarified. At Polk, on the other hand, there had been a change of attitude in the other direction, which his foreign minister finally understood, so that the Oregon Compromise of 1846 finally established the 49th parallel as the border in the Pacific Northwest .

With regard to Mexico, he maintained the dubious view that its attack on American troops on the other side of the Rio Grande in April 1846 was a border violation and thus a legitimate reason for war. Together with Polk and other Democrats, he had laid the basis for this conflict in the past with aggressive rhetoric referring to the instability of the neighboring state. During the Mexican-American War, Buchanan first advised the president not to claim territory south of the Rio Grande because he feared war with Great Britain and France, while Polk and the rest of the cabinet wanted a new border of 22nd parallel. After the United States Army captured Mexico City in 1847 , he changed his mind and opposed a peace treaty with Mexico in opposition to the President and other ministers. He alleged that Mexico was to blame for the war and that the negotiated compensation for the American losses was too low. Buchanan claimed provinces along the Sierra Madre Oriental and all of Baja California as future federal territories . He was left alone with his opinion in the Cabinet and in February 1848 Polk ratified the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo . Polk suspected that Buchanan's stance was intended not to oppose the southern states' desire for new slave states.

Politically sidelined

In the presidential election in 1848 , Buchanan tried again for a nomination. At the Democratic National Convention in May, however, he only brought the delegations from Pennsylvania and Virginia behind him, so that in the end Lewis Cass was chosen as the candidate of the Democrats. This was defeated in November by Whig General Zachary Taylor , who had developed into a national hero in the Mexican-American War. He considered the success of the abolitionist Free Soil Party , which reached 10% in the Popular Vote, to be a dangerous but short-term aberration of the voters. For him, the Democrats were the party that had brought freedom and prosperity and were the only ones able to maintain national unity in the growing North-South conflict over the slave question. He therefore saw any change in the party's political course as a potential threat to national cohesion. When Buchanan returned to Lancaster in the spring of 1849, he had not held a public office for the first time in 30 years and, because of the Whigs' triumph, had no prospect of such, especially since he turned down the request of the Pennsylvania Democrats to run for the Senate.

Now getting on in years, Buchanan still dressed himself in the old-fashioned style of his adolescence, while the press nicknamed him the Old Public Functionary . Anti-slavery opponents in the north ridiculed him for his moral principles as a relic from human prehistory. For the next four years, Buchanan lived as a privateer and mainly took care of domestic affairs. On the outskirts of Lancaster he bought the property Wheatland, that by his previous owner because of its location on a hill surrounded by "wheat ( wheat had been so named fields -)". The spacious 22-room residence was far too big for him as a single man, but in the meantime he had become the center of a family network that consisted of 22 nieces and nephews and their descendants. Seven of these were orphans whose legal guardianship was Buchanan. He was able to find public service jobs for some of them through patronage . For the nephews and nieces, who were most in his favor, he took on the role of a dutiful surrogate father. He built the greatest emotional bond with his niece Harriet Lane , who spent her youth and adolescence in Wheatland and later took on the role of first lady for Buchanan in the White House . In the 1840s he sent Harriet to one of the most famous boarding schools in the country, a convent school in Georgetown . As with the other pupils, his letters to Lane reflect his sober and distant emotional expression. She warned Buchanan about what not to do and gave her recommendations for action regarding the choice of her future husband. Harriet was grateful to her uncle and loyally followed his advice, which is why she did not marry a wealthy banker until the age of 37.

Buchanan provided his large study with a separate entrance so that politicians and public officials could meet him discreetly. The library reflected his serious nature and public standing in that, apart from a few short stories by Charles Dickens, it contained hardly any fiction, but was mainly stocked with parliamentary reports such as the Congressional Globe , legal commentaries and a copy of the Federalist Papers . Favored by the connection of Lancaster to the railroad, he often received travelers who were on their way to the capital and stayed overnight. The years as head of the family and lord of a stately residence gave him a more masculine, more respectable image and a new nickname with the Sage of Wheatland ("the sage of Wheatland"). At no point did he completely withdraw from politics. So he planned to publish a collection of speeches and an autobiography. When the chances of a political comeback increased before the presidential election in 1852 , he interrupted work on this project. Buchanan made several trips to Washington to consult with Democratic members of the Congress and focused his actions on party politics in Pennsylvania, where the Democrats were split into two camps under the leadership of Simon Cameron and George Dallas .

Presidential code 1852

As was customary for aspirants for the presidency at the time, Buchanan presented his positions in public letters, as he had done before the last presidential election in August 1847. Among other things, he had requested in this letter that the line of the Missouri Compromise be drawn to the Pacific coast. To the north of it slavery should be forbidden, while to the south of it the principle of popular sovereignity should decide. How and at what point in time this should happen in the federal territories concerned, Buchanan had not specified at the time. He returned to this point in his letter to a public meeting in Philadelphia in November 1850. The text, which lasted three hours to read, was the longest, most detailed, and most cited statement of Buchanan up to his presidency. In view of the compromise of 1850 that led to the admission of California as a free state into the Union and a stricter slave flight law , he now rejected the Missouri Compromise and welcomed the rejection of the Wilmot Proviso , which added slavery to all in the Mexican-American War Territories prohibited by Congress. He condemned abolitionism not only as the product of a fanatical mindset, but also because the agitation against slavery frightened its owners and the living conditions of the slaves deteriorated. Slavery should not be decided by Congress, but by the respective state legislature. Furthermore, he campaigned for the well-known principles of the Jacksonian Democracy , i.e. for a limitation of federal powers and federal funds as well as a verbatim interpretation ( strict constructionism ) of the constitution.

In the worsening north-south conflict of that time, Buchanan made no secret of his aversion to abolitionist northerners. This was due not only to his party affiliation and personal sympathy for the southern states, but also to his place of residence. Pennsylvania Quakers had petitioned Congress to free slaves from the start. The Harrisburg State Legislature had legally protected free African American and escaped slaves from slave hunters in the 1820s . As a border state north of the Mason-Dixon Line , Pennsylvania was also a stronghold of the Underground Railroad . When in 1851 militant abolitionists in Christiana near Wheatland protected escaped slaves from their owners, whereby the planter and his son were killed, Buchanan considered this to be an outrageous act and saw the opponents of slavery as the greatest danger to the existence of the Union . In 1850 he had welcomed the new slave flight law, which threatened anyone nationwide with punishment who helped them escape, while many of his compatriots in the northern states outraged this very law.

By the spring of 1852 Buchanan had established himself alongside Cass, Stephen Douglas and William L. Marcy as the most promising candidate for the Democratic presidential candidacy. A setback for him was when the Pennsylvania party congress did not unanimously vote for him in March, but more than 30 delegates wrote a protest note against him. They preferred Cameron as a candidate or, as a supporter, resented Wilmot Buchanan's concessions to the southern states. Although, as usual, he publicly denied his ambitions for the White House, he did more than other candidates for the nomination. In letters to party colleagues, he pointed out that Cass could not win the important Pennsylvania as a presidential candidate in the electoral college . Buchanan assessed the prospects for a nomination increasingly positive given the support from the southern states. At that time the radicals were still behind the political program that Buchanan had formulated in his letter of 1850. On the other hand, he was notorious in the north as the doughface ("dough face"), which was used to describe the northerners who sympathized with the south. At the Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in June 1852, neither Buchanan nor Cass achieved the necessary two-thirds majority in the first round of elections . Although he was able to collect some southern states continuously behind him, in the end he lacked the voices from the border states along the Mason-Dixon Line and the northern states. In the 49th round, the outsider Franklin Pierce from New Hampshire finally won . Buchanan then announced his departure from politics and turned down the offered vice-presidency; instead, he successfully proposed his friend King for this office.

Envoy to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1853-1856)

Although this position represented a step backwards in his career, Buchanan accepted the legation to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland six months after the presidential election in 1852 , after having resigned twice in his characteristic manner. In the summer of 1853 he traveled to London to take office . He turned out to be a well-informed, hardworking, and efficient envoy whose term of office fell at a particularly important phase in the relations between the United Kingdom and the United States . Britain's military engagement on some islands off the coast of Honduras and its interference in Nicaragua's affairs were up for debate. In 1850 the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty stipulated British-American control of this waterway in the event of a transoceanic canal construction through this country. In general, since Polk's presidency, Washington reacted more sensitively to European influence in Central and South America , which it saw as violating the Monroe Doctrine .

In September 1853 there was the first of over 150 meetings between Buchanan and the British Foreign Secretary George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon , between whom a friendly relationship developed. While he viewed the British presence in Central America as a matter of urgency, Villiers was preoccupied with the Crimean War at the time. Buchanan's first diplomatic crisis involved protocol . Foreign Minister Marcy had ordered that the foreign envoys should dress only as ordinary citizens, which did not comply with the dress code of the British court and the gentry's salons in the capital . For this reason, he stayed away from the opening of parliament , which was taken as an affront. When Queen Victoria invited him to dinner, he solved the problem by carrying a sword, which was considered a hallmark of a gentleman in both America and Britain . At home, Buchanan profited from the "clothes affair" because it gave him the reputation of a simple citizen who did not submit to the aristocratic customs of the kingdom.

Meanwhile, conversations with Villiers addressed the presence of the United Kingdom in Central America and the West Indies, as well as Buchanan's obsession with annexing the Spanish colony of Cuba. He pursued a bilateral treaty as the first step on the way to keep Great Britain out of the western hemisphere except for its Canadian colonies . In doing so, he adhered exactly to the instructions given by President Pierce, which provided for a British withdrawal from the Islas de la Bahía off the north coast of Nicaragua. Furthermore, the United Kingdom should withdraw from Belize and give up its protectorate over the Miskito and thus control over the port of San Juan de Nicaragua, which is important in the event of a transoceanic canal construction . At first, Villiers, who focused on the Crimean War, showed little understanding of the American demands and revealed a lack of detailed knowledge of the geographical importance of the regions in question. Buchanan appealed to the special relationships between their countries and the diverse similarities in language, religion and culture, which are so great that London should see no opponent in its former colony. For the future he predicted particularly close relations between the two nations. In the summer of 1854 he finally said that thanks to his persuasion, London was ready to put pressure on Spain to sell Cuba to the United States.

In June 1854 the President ordered him to Paris to work out a plan to acquire Cuba with his counterparts in Spain and France, Pierre Soulé and John Y. Mason . Buchanan was reluctant to follow suit, believing he already had the right concept. Finally, in October, the three ambassadors held a working meeting in the Belgian seaside resort of Ostend and then in Aachen . As a result, they published the so-called Ostend Manifesto , probably formulated by Buchanan , in which the acquisition or - if Spain should reject this - the forcible annexation of Cuba was outlined. This document is considered to be one in which the expansionism or imperialism of the Manifest Destiny is most clearly shown. The sale for 100 million US dollars was demanded from Madrid on the grounds that Cuba was geographically a natural appendage to the United States, which it needed for self-support and, if necessary, would have to procure by military means. For Buchanan and the southern states, concerns about a slave revolt in Cuba and its spread to the United States were also a key motive. In addition, the island offered itself as a future slave state within the American Union because of its prosperous sugar cane plantations . In the homeland, which meanwhile experienced an intensification of the North-South conflict and a decline of the Democrats in the northern states due to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of May 1854 and the associated lifting of the Missouri Compromise, the Ostend Manifesto received a divided response and was rejected by President Pierce. While it was welcomed in the southern states, northerners saw the excitement it sparked beyond the Mason-Dixon line as further evidence of the aggressive dominance of southern slave-holding societies. In the northern states there was a growing perception that a minority in the form of the planters was imposing its norms and values on the entire nation. When Buchanan began to want to return home in 1855, Pierce asked him to keep the position in London in view of the transfer of a British fleet to the Caribbean . As envoy, he was ultimately able to push back British influence in Honduras and Nicaragua and sensitize the kingdom to American interests in this region.

Primaries and presidential election 1856

Because Pierce was not seeking a second term in office, Buchanan was considered the most promising candidate for the Democratic primaries in the 1856 presidential election . Although some Northern Democrats criticized him for the Ostend Manifesto, he benefited overall from his absence during the debates about the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he was critical of. While still in England , he campaigned by praising a Catholic archbishop to John Joseph Hughes , who was Archbishop of New York . He stood up for Buchanan among high-ranking Catholics as soon as he heard about it. When Buchanan arrived home in late April 1856, the Pennsylvania Congress had unanimously proposed him as a Democratic presidential candidate. Shortly after a brawl between two congressmen , which ended with serious injuries for Charles Sumner, and the Pottawatomie massacre of John Brown in the Kansas Territory once again highlighted the tense situation of the nation, the National Convention of the Democrats met in early June . The electoral program adopted there reads as if it were written by Buchanan and contained as demands the limitation of federal power, the energetic enforcement of the slave flight law, the fight against abolitionist agitation and the strict implementation of the Monroe Doctrine. The question of the extent to which the people of the territories themselves had the right to regulate slavery remained ambiguous.

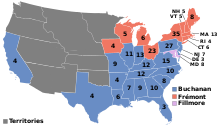

Buchanan's main competitors at the nomination convention were Pierce, who ran again, Douglas and Cass. He benefited from the fact that his campaign managers controlled the organization of the party congress and that Senators John Slidell , Jesse D. Bright and Thomas F. Bayard stood up for him. Neither the favorite of the northern nor the southern states, he was for both sides an acceptable candidate who was trusted to unite the party. In the 18th voting round, Buchanan finally received the necessary two-thirds majority after Douglas resigned. Since he came from Pennsylvania, the regional was to maintain proportional representation with John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky determined politician from the southern states to his running mate. In the presidential election, Buchanan faced former President Millard Fillmore of the anti-Catholic - nativist Know-Nothing Party and John C. Frémont , who was running for the rapidly growing new Republican Party that challenged slavery in the Territories . In particular, the contrast between the experienced Buchanan and the young explorer and officer Frémont was great. Opposing cartoonists took up this theme and depicted the Democratic candidate as a picky old man in women's clothes. That Buchanan's masculinity was questioned in bold images and words because of his celibacy had happened time and again.

Buchanan did not actively take part in the election campaign himself, since at that time advertising on his own behalf for political office was considered improper. Compared to a party committee, he vowed to stick to the election program decided on at the National Convention, although he rejected the postulated application of the principle of popular sovereignty to the territories as a potential danger to internal peace. He saw his election victory as the only way to save the American Union. In addition to the southern states, he had to win over some northern states. To win California, Buchanan moved away from Jackson's guiding principle of limited federal funding and advocated the state-sponsored construction of a transcontinental railroad. In the end, there were practically two races for the White House: one in the northern states between Buchanan and Frémont and the other in the southern states between Buchanan and Fillmore. The September presidential election in Maine revealed the strength of the Republicans, while the Democratic success in Pennsylvania Buchanan secured the presidency. The actual election day in November saw an exceptionally high turnout of 79%. Buchanan, who achieved a popular vote of 45%, won all slave states except Maryland , but only Pennsylvania and four other states in the north, which underscored the prevailing regional particularism within the Democrats. The Republicans, on the other hand, prevailed in eleven of the 16 free states. From the Wheatland porch, Buchanan delivered his victory speech, in which he accused Republican voters, in a familiar biased manner, of using their voice to attack compatriots in the south and endanger the American Union.

Presidency

Buchanan moved into the White House as the most seasoned politician since John Quincy Adams . Starting with James Monroe, he had more or less close contact with each of his predecessors. At that time, the presidential self-image was less that of an initiative designer than that of an administrator. Buchanan was an exception and was based on Jackson and Polk, who had emphasized the executive power of the president . Similar to his role model George Washington or the Roman Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus , he saw himself as someone who did not actively strive for rule, but had received it from the people, who were the highest authority for him. He also credited himself with the calm temperament and determination he believed a good president needed. This self-image led Buchanan to interpret the presidential authority very aggressively, especially when it came to helping the southern states. He also defended the presidential veto power against the Whigs, who questioned this right, and judged them to be much safer in the event of despotic abuse than the White House's control over authorities and public opinion, as well as its authority and command .

When Buchanan was inaugurated on March 4, 1857, he was 67, an unusually old age for the time. For this reason, he announced that he would not seek re-election. Before taking the oath of office, he had a brief interview with presiding federal judge Roger B. Taney , which later became significant. The long inaugural address addressed the slave question in the territories. As a solution, Buchanan suggested orienting himself towards the Kansas-Nebraska Act, according to which the principle of popular sovereignty, i.e. the state legislature and the constitution passed by it, was decisive, while Congress had no say in this matter. Before the territory has reached this stage, every American is free to settle in this area with his slaves. During his presidency he took the side of the southern states more and more clearly on this issue and stated that they had the right to open all territories to slavery. A few weeks after John Brown's attack on Harpers Ferry , he even expressed sympathy for states that flirted with secession under such circumstances . In his inaugural address, he also noted that the legislative issue of popular sovereignty in the Territories was negligible because the Supreme Court was pending a decision, alluding to the case of the slave Dred Scott . This statement by Buchanan on the decision-making authority of the judiciary on the slave question in the territories was revolutionary in terms of its implications, on the one hand, because in American history up until then there was a consensus that Congress had to determine it. On the other hand, this line of argument was unique, as no president before or after him ever voluntarily granted such power to the Supreme Court. In addition, Buchanan contradicted himself because he emphasized in the speech the validity of the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed by Congress.

The organization of the White House parties and receptions was left to President Lane and his nephew James Buchanan to Henry. After the last official had only rarely invited to events because of the mourning of his son, who died shortly before the inauguration, the capital's high society now hoped for an improvement in the situation. Lane and her cousin hosted presidential receptions with a more informal character during the non-session time of Congress. During the session, state dinners were held in the White House, to which only members of the Congress, high judges and diplomats were invited. Buchanan engaged in two main recreational activities. On the one hand, he traveled annually for two weeks to Bedford Springs to see the thermal springs at the resort there . On the other hand, he regularly went for walks in Washington in the afternoons.

Cabinet selection and spoil system

A few weeks before his inauguration, Buchanan began to put together the cabinet , which he saw primarily in the role of an advisory body for his ideas. As a bachelor, a friendly relationship with the ministers was important to him, with whom he met for meetings lasting several hours on weekdays during the first two years of his presidency. According to Baker, probably no president in American history has spent more time with his cabinet than Buchanan. The composition of the cabinet also had to do justice to the proportional representation within the party and between the regional regions. Buchanan worked on this assignment and his inaugural address first in Wheatland until he traveled to the capital in January 1857. Like many other guests of the National Hotel , he suffered severe dysentery there, from which he did not fully recover until several months later. Dozens of the sick died, including Buchanan's nephew and private secretary Eskridge Lane.

Ultimately, Buchanan's cabinet selection turned out to be a complete disaster. The four southern ministers had all been large-scale slave owners at some point in their lives, were later loyal to the Confederate States and dominated the cabinet until they withdrew. Among these, Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb was seen as the greatest political talent in the cabinet and potential successor to Buchanan. Like Buchanan Doughfaces and Cass as the only minister from the region west of the Appalachians , the three heads of department from the northern states were completely in the shadow of the president, who regarded foreign policy as his profession , as Secretary of State , traditionally the highest-ranking cabinet post . In addition, his cabinet is considered one of the most corrupt in American history. This was particularly true of Home Secretary Jacob Thompson and Secretary of War John B. Floyd , who, like Cass, was also extremely ill-suited for his department and rarely sought advice from the highest military General Winfield Scott . The corruption scandals ranged from a niece's husband to Buchanan's family. As intended by Buchanan, who wanted to distinguish himself as a strong president, the ministers fully supported all his decisions. It was only in the last six months of his term in office that there was opposition to the president's policy in the cabinet. Buchanan had a troubled relationship with his Vice President from the beginning when he did not receive him on his inaugural visit, but referred him to his niece and First Lady Lane, which Breckinridge never forgave as a humiliation. He left out the influential Douglas, who had made Buchanan's nomination possible through his resignation at the National Convention last year, when filling the positions. Republicans and Northern Democrats, who were critical of the Southern States, were also not considered in the spoil system . All in all, the personnel policy led to Buchanan's dangerous self-isolation.

After the inauguration, Buchanan dealt mainly with filling vacancies as part of the spoil system. Unwilling to delegate executive powers and fixated on detail, he worked his way down to the most insignificant posts on the staff panel. He also read through documents that were normally checked by secretaries and signed on behalf of the President before signing them. Accordingly, at the end of each session, he complained about the delay in Congress, which, because of the deadline set, gave him too little time to carefully study passed laws before they were signed. Because the previous President Pierce was a Democrat, Buchanan kept the efficient and loyal officials on until the end of their term. He kept some positions in reserve in order to raise support and funds with their occupation. Overall, Buchanan wanted to win a loyal following with his public service personnel selection and weaken Republicans and the faction around Douglas. However, he deviated from this line when he removed a relatively large number of Northerners, including some with ties to Pierce, from their offices for no apparent reason, while the Southerners kept almost all of their posts. This human resource management alienated him once more from the Northern Democrats.

Influence the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott versus Sandford case

The Dred Scott versus Sandford case , which Buchanan referred to in his inaugural address, dates back to 1846. Scott had sued for his release in Missouri on the grounds that he had lived in the service of the owner in the free state of Illinois and the likewise abolitionist Wisconsin Territory . After various judgments, the case had reached the Supreme Court through the courts and gained national recognition by 1856. Buchanan saw in this matter the possibility of settling the slave question once and for all and thus re-establishing the fragile national unity. When a decision emerged, he corresponded in early February 1857 with his friend, a judge John Catron, and inquired about the state of affairs. He reported a divided opinion and encouraged Buchanan to move Federal Judge Robert Grier from Pennsylvania to approach his colleagues from the southern states, which resulted in a decision-making majority. With the judgment, they wanted to go beyond the specific case and bring about a general regulation for slavery as a whole. Buchanan wrote accordingly to his friend Grier, who a short time later was one of the six judges who formed the majority of the verdict. By influencing an ongoing judicial process , he violated the principle of the separation of powers and undermined his presidency from the outset, while his announcement in his inaugural address that every judgment would be received with joy turned out to be insincere in retrospect.

Just two days after Buchanan's inauguration, Taney announced the decision already known to the president. According to this, slaves were forever illegally owned by their owners, and no African American could ever be a full citizen of the United States, even if he had full civil rights in a state. The Missouri Compromise was declared unconstitutional by the ruling concerning the territories. As a right to property protected under the 5th Amendment , slavery could not be prohibited in any territory; According to the verdict, this was only possible after the state was admitted to the American Union. The brief conversation that Taney and Buchanan had at the inauguration was now viewed with suspicion by the public. Many assumed that the presiding federal judge had informed the president of the upcoming verdict without suspecting Buchanan's much deeper interference in the formation of the verdict. Republican voices soon suspected more, however, speaking of a conspiracy by Taney, Buchanan, and others to spread slavery. As with the formation of the cabinet, he had used his powers unilaterally for the interests of the southern states. When Republicans attacked the Supreme Court decision as a misjudgment, Buchanan blamed them for the collapse of national unity that soon followed.

Economic crisis of 1857

The economic crisis of 1857 was the first of three temporally overlapping crises that characterized the first three years of Buchanan's presidency. It began in the late spring of that year, when the New York branch of a respected insurance company from Ohio , the insolvency indicated. The crisis spread at a rapid pace, with 1,400 banks and 5,000 companies, including many railways and factories, going bankrupt by the fall . While unemployment and hunger became part of everyday life in the cities of the north, the agrarian south was more resilient to the crisis. There the greed and speculative fever of Northern capitalists was blamed for the crisis; Buchanan agreed with this view. According to the political understanding of the time, fighting such a recession was beyond the capabilities of a president, so that generally the White House was not expected to be particularly active and it remained with laissez-faire measures . Buchanan responded according to the principles of the Jacksonian Democracy , which included payments in coins and gold, restricted bank issuance of paper money, and froze federal funding for public works. Because he refused to mitigate the crisis with an economic stimulus package , he caused displeasure in parts of the population. In addition, his economic policy was directed against banks and advocated free trade , which once more fell into disrepute in the north as Doughface . Although he later praised himself for the reduction in national debt, the federal budget grew by 15% under his presidency .

Utah war

In the spring of 1857, the Utah War developed into the second crisis of his presidency, to which Buchanan responded by taking full advantage of his executive powers. For years, Mormon leader Brigham Young and his followers had challenged the authority of federal officials in the Utah Territory . They saw the country as theirs and felt that their faith was disturbed by representatives of a secular power. Young, who had been the governor of the territory since 1850 , and his followers continually harassed federal officials as well as strangers who merely crossed the territory. In September 1857, the Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred , in which the Youngs militia ambushed a trek and killed 125 settlers. Buchanan also felt repulsed by Young's polygamy , which he aggressively promoted as the husband of 17 women and which was widespread in the Utah Territory despite an official ban. The president classified marriage law as a federal matter and saw the Mormons as recalcitrant sodomists threatening anyone loyal to American law. There were also rumors that Young wanted to establish a theocratic- run Mormon state independent of America . In late March 1857, when reports were arriving from federal officials sketching Utah as a runaway territory marked by violence against non-Mormons, Buchanan authorized a military expedition to the Utah Territory to replace Young as governor. The president failed to inform Young of the move, a mistake that helped the Mormon leader portray the approaching forces as an unauthorized coup.

The force consisted of 2,500 men, including the new Governor Alfred Cumming and his staff, and was commanded by General William S. Harney . This was known for his volatility and brutality, which is why Buchanan's decision on personnel incited the resistance of the Mormons around Young all the more. In August 1857 he was replaced by Albert S. Johnston for organizational reasons . Cumming, who was only considered by Buchanan after ten other candidates turned down the offer of governorship, and Johnston quickly fell out. The expedition, which became the most costly military operation between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War and in 1858 caused a budget deficit that had never been achieved before, did not reach the region until the autumn, when the mountain passes to the Great Salt Lake , which were covered by the Mormon militia, were already snowed over. The United States Army therefore wintered in a camp near Fort Bridger .

After a break of more than half a year, Buchanan only commented on the conflict again in his State of the Union Address in December 1857, leaving the question open of whether it was a rebellion in Utah. He ordered Scott to the Pacific coast to advance from there against the Salt Lake Valley . The president wanted to achieve an exodus of the Mormons to northern Mexico in order to have a reason for the annexation of this territory by the United States. Congress refused to approve Scott's posting, without knowing Buchanan's real goal behind the action. By the spring of 1858, meanwhile a third of the army had been assigned to the Utah expedition, his friend Thomas L. Kane Buchanan was able to convince him that he would be able to reach a negotiated solution with the Mormons with whom he was on good terms be. The President gave him the appropriate authority and dispatched him to the Utah Territory. Once there, Kane negotiated a peaceful agreement that saw Governor Young be replaced by Cumming. In return, the Mormons were given sovereignty in religious matters. When Johnston led the expeditionary forces through Salt Lake City in late June, Buchanan counted this outcome as a success; However, he caused astonishment two years later when, contrary to the fall of the Utah Territory in the conflict with the southern states, he shied away from any use of military force. One of Buchanan's final acts in March 1861 was downsizing the Utah Territory in favor of Nevada , Colorado, and Nebraska .

Conflict in the Kansas Territory

Starting position

The third crisis of the Buchanan presidency was the conflict over the slave issue in the Kansas Territory . For the southern states, this future state was central to the expansion of slavery to the west and control of Congress because of its location between north and south. In the founding phase of the territory, forces sympathetic to the southern states had taken possession of land and spread slavery so aggressively that a countermovement had emerged from the northern states. In the election to the State Legislature in 1855, abolitionists were forcibly removed from the vote, so that Parliament in Lecompton could pass drastic laws that, among other things, classified any criticism of slavery as a capital crime. As a result, the opponents of slavery in Topeka had established their own territorial administration in the same year and banned slavery, with a growing majority in Kansas supporting them. In 1857, at the instigation of the Lecompton government, elections were held for a constitutional convention which, through systematic manipulation, resulted in a clear majority for adherents to slavery. Civil war-like riots soon broke out between opponents and advocates of slavery, which lasted into the middle of Buchanan's tenure and went down in history as Bleeding Kansas . A high point of the violence in Bleeding Kansas was the destruction of the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence by militias of the slavery supporters and the Pottawatomie massacre in May 1856. When he took office, Buchanan still hoped to have democrats from northern and southern states behind him in the Kansas conflict .

A few days after his inauguration, Buchanan dismissed John White Geary , which was the third governor of the Kansas Territory . At that time, 1,500 United States Army soldiers were in the territory to keep the peace there. Although the President and Congress shared authority over the territories, the White House, through the appointment of governors, decided significantly on the political course of the respective territory . Buchanan supported the Lecompton government, which he affirmed in his State of the Union Address in December 1857, and only recognized it as the official territorial administration. He appointed his former Senate and Cabinet colleague Robert J. Walker as governor. The president promised him that he would only recognize a referendum- approved constitution of Kansas, which was the normal procedure in such cases.

Constitutional dispute

In the summer of 1857 Buchanan looked attentively to Georgia and Mississippi , where political gatherings threatened secession if Kansas were not accepted into the American Union as a slave state. Walker had meanwhile come to the opinion that Kansas should become a free state, also because the climatic conditions there made slavery uneconomical, which sparked indignation in the southern states, which was also directed against the president. Buchanan secretly shared this geographic assessment with Walker, but continued to support the Lecompton government because of southern pressure. In August 1857, Buchanan declared the decision in the Dred Scott versus Sandford case to be the decisive guideline for the territories, according to which slavery is protected by law wherever a slave owner settles, and made the abolitionists Topekas responsible for bleeding Kansas . The results of the elections for the Lecompton Parliament two months later were so obviously falsified that Walker did not recognize the results of some counties, giving the State Legislature an abolitionist majority. After that, Walker lost Buchanan's support. The Lecompton Antiabolitionist Constitutional Convention passed a constitution that legally protected slavery as a private property right. Whether the outcome was uncertain, the MPs refrained from a referendum and sent the constitutional text directly to Buchanan and Congress so that they could use this as a basis to examine the recognition of Kansas as a state.

But this waiver of a referendum so obviously violated the usual procedure that Buchanan did not agree to it. Under pressure from Washington, the Lecompton Assembly ordered a plebiscite on the passage on slavery. Because the existing slavery in the territory was protected by law, the referendum promoted by Buchanan as a compromise solution could only prevent further slaves from being imported. At the State of the Union Address in December 1857, the president insisted that under the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the principle of popular sovereignty required a referendum only on the question of slavery. When Walker failed to convince the president to no longer support the questionable Lecompton constitution, he resigned as governor. The referendum at the end of December resulted in a clear anti-metabolism majority, with the citizens of the Topeka government being excluded from the election. Three weeks later they rejected the Lecompton constitution in a separate referendum. Despite the insistence of many critical Northern Democrats, Buchanan adhered to the Lecompton Constitution, which led to a heated argument in the White House in early December and a subsequent break with Douglas. Legend has it that President Douglas remembered the fate of two renegade senators who had turned against Jackson in this conversation, to which Jackson replied that President Jackson was dead.

In early February 1858, he presented the Lecompton Constitution to Congress and compared the citizens of Topekas with the rebellious Mormons of the Utah War. Counterfactually, he told Congress that he had never insisted on a referendum on the entire constitutional text as a condition for the recognition of Kansas as a state, but only had the slave question in mind. He also pointed out that the constitution could later be changed by the state legislature, but this was only possible after seven years and could be blocked by a minority. After the Lecompton Constitution was passed in the Senate, the President worked flat out to secure a majority in the House of Representatives, in which less than a third of the MPs came from slave states. Members of the Buchanan cabinet engaged in an extraordinary amount of lobbying with MPs, with patronage of office and lucrative business offers as a lure. This was so intense that two years later a congressional committee investigated the matter without finding any evidence incriminating Buchanan himself.

Despite all the efforts of the White House, the Lecompton Constitution failed in the House of Representatives, with the rejection of Douglas by the Northern Democrats being the decisive factor, which the President never forgave him. As a result, he withdrew all Douglas supporters from his patronage. Buchanan then submitted a bill to Congress from Representative William Hayden English . The English Bill granted Kansas instant recognition as a state if the Lecompton Constitution was approved; in the event of a rejection, the territory was only accepted from a certain population size. Shortly after the English Bill was passed by Congress, the citizens of Kansas voted by a clear majority against the Lecompton Constitution in August 1858. The territory was thus given an abolitionist constitution, which was bitterly opposed in Congress by the delegates and senators from the southern states, until Kansas was admitted as a state in the United States in January 1861. Buchanan recorded the outcome of the constitutional conflict in his annual State of the Union Address in December 1858 as a personal success, ignoring the damage he had done to his party through his behavior. In this State of the Union address, Buchanan discussed foreign policy for a disproportionately long time, to which he now wanted to devote himself to the allegedly resolved domestic political crises.

However, as it had for a generation, the slave question remained the central political issue. The Kansas Constitutional Dispute marked a turning point in Democratic history. With the support for the south in Bleeding Kansas nowhere more evident , Buchanan had split his own party and worsened the north-south conflict considerably. As a result, he fueled fears in the north that a planter oligarchy would soon control the entire country and make slavery a national institution. Abraham Lincoln accused Buchanan in the Lincoln-Douglas debates and in the House Divided speech of 1858 of a joint conspiracy with Taney, Douglas and Pierce for this purpose, whereby the circumstances of the Dred Scott versus Sandford judgment were particularly onerous Moment led. In the fall of 1858 congressional elections , the Democrats suffered heavy losses in the northern states, particularly in Pennsylvania. Nevertheless, the president showed no willingness to moderate his favoring of the southern states, but expected that the north would make concessions to the slave states.

Foreign policy

After the Kansas Constitutional Conflict, Buchanan focused on South American politics . He acted as his own foreign secretary as Cass may have been overwhelmed by his office due to age. Buchanan sought to revive the Manifest Destiny , which had lost momentum after the enormous territorial gain under President Polk, and to implement the Monroe Doctrine, which was under attack from the Spanish, French and especially British in the 1850s. To counter European imperialism in the western hemisphere, he wanted to revise the Clayton-Bulwer treaty. Typically, he also prioritized the interests of the southern states in terms of foreign policy. He spoke out in favor of expansion to Mexico and Central America, advocating a protectorate over the provinces of Chihuahua and Sonora to secure American citizens and investments. When the situation there destabilized when General Miguel Miramón came to power , Buchanan also feared intervention by Spain or Napoleon III. Furthermore, from the beginning of his presidency he pursued the acquisition of Cuba, which he compared with the Louisiana Purchase . With an annexation he hoped to reunite the divided party and to prevent the influence of foreign powers on the island. As with the State of the Union Address the previous year, Buchanan focused on foreign policy on this occasion in December 1859. He stated that Mexico still owed the United States damages and security promises. Therefore, he asked Congress for approval of American military bases on Mexican territory immediately south of New Mexico territory .

In the case of Mexico, he did not accept the objection that only Congress had the right to declare war , because its instability threatened the security of the United States and needed help from the neighborhood. In the end, Republicans and third-party MPs in the 35th United States Congress blocked almost all of Buchanan's bills on South and Central America. Even some southerners voted against the president because they feared a powerful, imperialist federal government. Undeterred, Buchanan followed his aggressive line and, even in the midst of the secession crisis in the last State of the Union Address, unsuccessfully demanded federal funds for the purchase of Cuba and a military intervention in Mexico. Still, he didn't go as far as some of the southern Democrats who backed filibusters , condemning the actions of William Walker , who rose to be president in Nicaragua, as illegal. In general, Nicaragua, unlike Mexico and Cuba, was never a target of Buchanan's expansionist plans, but was only concerned with strategic and economic influence in the region. To this end, and as a sign against further filibusters, contracts were negotiated with Costa Rica , Honduras and Nicaragua under his government .

Relations with the United Kingdom developed beyond South America during Buchanan's presidency. For example, when the so-called pig conflict broke out on Juan de Fuca Street , Buchanan dispatched armed forces under the leadership of General Scott to the north-west of the United States to replace the overreacting District Commander General William S. Harney, which quickly calmed the situation. Further tensions arose over the maritime slave trade . Buchanan rejected this and the Webster-Ashburton Treaty had been in place between Washington and London since 1842 to ban it. America, however, showed less will to stop the slave trade than the British, although the president showed more initiative in this field than his predecessors and increased the number of confiscated slave ships significantly by strengthening the navy and cooperating with the Royal Navy . Even so, many slave traders continued to sail under the American flag, some of which were stopped and searched by the British Navy in the Caribbean. Buchanan, bearing in mind the reasons for the war of 1812 against Britain, viewed this as a disregard for American sovereignty. After some sharp protests and the mobilization of the American Navy, London withdrew its fleet from the region.

Buchanan responded to a minor incident with a military intervention vis-à-vis Paraguay . When an American ship was shot at on the Río Paraná there and Americans living there had asserted property rights against Asunción , the president ordered 2,500 marines and 19 warships there. This costly expedition took months before reaching Asunción, where they successfully sought concessions from the United States. Possibly this venture also served to demonstrate to the world one's own sea power.