whaling

Whaling is the hunt for whales by humans, mostly from ships . In the early days, the main goal was to extract oil , which served as fuel and industrial raw material. The use of whale meat as a food has only been of significant importance since the late 20th century.

Industrial whaling caused the populations of large whales to shrink dramatically in the first half of the 20th century. Many species were or are critically endangered. Whales are considered particularly intelligent animals because of their large brains and complex social behavior. Against this background, whaling is internationally controversial. Today it is only operated by a few countries.

story

Early history

Rock carvings and bone finds in the south of the Korean peninsula Bangu-Dae (near Ulsan ) prove that whales were hunted as early as 7000 years ago. Russian and American archaeologists discovered this (oldest) evidence of whaling. During an excavation on the Chukchi Peninsula, they found a 3,000-year-old piece of walrus ivory with carved scenes from a whale hunt. At the excavation site, they also discovered the remains of several whales and heavy stone blades that may have been used to kill the animals. Cave paintings in Scandinavia document a millennia-old practice of whaling in Europe. The Eskimos in the northern polar region also traditionally hunt whales, for example with spears thrown from kayaks .

Antiquity

Whale bones found in Roman ancient sites on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar and other regions of the Mediterranean show that whales were hunted 2000 years ago even in ancient times. These were mainly the northern right whale and the now-extinct Atlantic gray whale , which probably swam into the Mediterranean to calve. Moreover bones were pilot whale , fin whale , sperm whale and the Cuvier's beaked found.

middle age

In the 12th century, the Basques hunted the small pilot whale and the northern Atlantic right whale intensively , which subsequently became extinct in their region.

Modern times

When Willem Barents in 1596 and Jonas Poole in 1610 - looking for the Northeast Passage north of Siberia - discovered a rich occurrence of bowhead whales near Spitsbergen , in 1611 the English and 1612 Dutch began an extensive whale hunt, which in 1644 German ships from Hamburg and Altona and in 1650 the English colonists in North America joined them.

The oil of the whale was an important raw material for artificial lighting. It was also used to produce soaps, ointments, soups, paints, gelatine or edible fats (e.g. margarine ) as well as shoe and leather care products. Whale oil was originally needed to make nitroglycerin . Even after the First World War , the British army command said: "Without the whale oil, the government would not have been able to fight both the food battle and the ammunition battle."

The sperm whale was particularly heavily hunted by American whalers from Nantucket in the 19th century because of the whale rat contained in its head, and its populations were decimated. The whale rat is suitable for the production of particularly brightly burning candles , cosmetics and as a lubricant . From the 17th century whalebone was made from the beards of the baleen whales , preferably the blue whale , until stiff but elastic plastics (e.g. nylon ) and light spring stainless steels replaced the animal material in the 20th century .

Initially, the whale was hunted in small, sturdy row boats with a crew of six to eight, and killed with hand harpoons and lances. The hunted whale was then dragged alongside the whaling ship and slimmed down there ("flensen"). Everything else was left to the seagulls and predatory fish.

Around 1840 there were around 900 fishing vessels, which killed up to 10,000 whales in the years when they were strong. The average American whaler in the 19th century carried about 20 to 30 men. The ships carried up to six boats including reserves. Usually three to four boats, each manned by six sailors, were used in the hunt. Only one or two men were left behind to guard the ship. Even “skilled workers” such as ship's cook or carpenter had to get into the boats to hunt and row. In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the bacon from the captured whales was mainly boiled in oil distilleries on the coasts of Greenland and Svalbard and then put into barrels. A normal fishing trip lasted around two to four years, depending on the yield and shelf life of the stocks.

The German construction of a harpoon cannon , which was installed on a Norwegian whaling steamer around 1863, made it possible to hunt the faster blue and fin whales . The harpoon had a grenade head on its tip. The grenade, which exploded in his body after harpooning, killed the whale faster. Around 1935 this device was improved again by passing an electric current through the harpoon line, which immediately stunned the animal. As a result of the first successful production of petroleum , which has properties similar to whale oil , in 1855 , the catch almost came to a standstill in the following years. The overuse of the whale populations in connection with a general overfishing of the northern seas increased the effect of the massive decline in whaling yields that could be observed regionally as early as the beginning of the 18th century.

The invention of margarine was one of the reasons for a revival of whaling, as whale oil was initially an essential part of the butter surrogate. Since whale oil was also used for the production of nitroglycerin, the armament that began at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century led to a greatly increased demand and, as a result, to a further increase in whaling. In 1923, the Norwegian whaling ship James Clark Ross was the first ship that could cook and bottle its prey directly on the ship without having to return to the coast. That made whaling much more efficient. Less than ten years later, the blue whales caught were already considerably smaller than those caught in previous decades. Today it is believed that half of the captured animals were immature whales at this point in time. In the 1930s, large fleets were created that were en route for months in factory ships. From 1960 to 1964, the mostly Japanese and Soviet whaling fleets lost no less than 127,000 sperm whales.

In the 1930s it was recognized that the whale population was endangered by the heavy hunting. 30,000 blue whales were killed in 1930 and 1931 alone. For comparison: this number exceeds the number of blue whale populations living in the oceans worldwide today. The League of Nations passed an agreement to limit whaling in 1931, which came into force in 1935. Around three million whales were killed in the entire 20th century.

Whaling in Japanese waters peaked in the years after World War II , when meat was used to feed the needy population; it was not particularly well respected, however. However, some European nations are primarily responsible for the hunt to the verge of extinction, whose whaling stations in Antarctica were operated until the 1960s, but almost exclusively for the purpose of extracting raw materials for industry.

In the North Atlantic, the once large herds of the northern right whale, a slowly swimming species that is therefore particularly endangered by whaling, were so decimated by the beginning of the 19th century that hunting was no longer profitable. The whalers then concentrated on the sperm whale and killed it in such large numbers that this species also became rare in the Atlantic. Now the whalers went to the Pacific and Indian Oceans. There they found large numbers of southern right whales, sperm whales, humpback whales and later bowhead whales. It seemed inconceivable to the whalers at the time that the stocks could ever be exhausted. There were also other whale species that were previously not hunted.

The so-called furrow whales , including blue, fin and sei whales , were among the whale species that were considered unhuntable . Due to their greater speed compared to the detached rowing boats, they were very often able to escape being shot by the harpoon thrower by fleeing. If a furrowed whale was hunted, it almost always quickly lost its buoyancy, drowned and thus lost to the hunters. Only the change in the hunting method through the use of harpoons equipped with explosive charges, which brought about the death of the animal more quickly, as well as the use of steam-powered and thus considerably faster ships changed the balance of power in favor of the hunters and heralded the beginning of modern whaling. After the killing, lashed to the side of the fishing vessel, air was continuously pumped into the dead body to prevent it from sinking until it was further processed. In order to save time and enable the fishing vessels to resume their hunt as quickly as possible, further processing at sea was relocated to so-called factory vessels. These special ships picked up the catch from the fighter ships calling at them. They were able to process several dozen whales a day.

All this ensured that the hunt for the whale took on unimagined dimensions. Between 1842 and 1846, the whalers returned home with the oil from around 20,000 sperm whales in their holds.

The statistics show a surprising period of dormancy for the whales during World War II. The number of catches fell in 1938 to 1945 from around 57,000 blue and fin whales to around 5,000.

Whaling today

Whaling has been regulated by the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling since 1948 . Among other things, catch quotas are set. Adjustments to quotas and definition of protection zones are carried out by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) founded in 1946.

At the end of the 1960s, the book Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome was published worldwide , which in Germany (published in 1972) strongly influenced the next generation of young people and anchored environmental considerations and animal welfare in the general knowledge of the population.

In the chapter on technology, whaling served as an example of unchecked development:

“The history of whaling shows in a small area what happens when a limited habitat is increasingly exploited. The whalers have reached one limit after another and have always tried to break these limits by using even greater technological tools. They wiped out one species of whale after another. The end result of this attitude, which demands growth at all costs, can only be the total extinction of all whale species and the whalers themselves. "

The scientists wrote in 1969: "The only alternative is to maintain a human-determined catch rate, which gives the whale species the opportunity to maintain a certain level."

Most recently, in 1986, as a so-called moratorium, the quotas for commercial whaling for all whale species and hunting areas were set to zero. The moratorium was initially intended to run until 1990, but has been extended and is still in force today.

The moratorium does not mean a general ban on whaling. To date, there are three types of whaling based on the Whaling Agreement:

- Whaling by indigenous people for local consumption . Countries in which whaling was carried out under this regulation from 1987 to 2002 † : Denmark ( Greenland ), Canada , Russia / Soviet Union , United States , St. Vincent and the Grenadines

- States can independently issue special permits for whaling for scientific purposes . The International Convention on the Regulation of Whaling requires that whales caught for such purposes be used as much as possible. States that issued such permits from 1987 to 2002 † : Iceland , Japan , South Korea

- States that have objected to the moratorium and are maintaining it are not bound by it. States in which whaling was carried out from 1987 to 2002 due to an objection † : Japan (until 1988), Norway

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

* Hunting based on an objection to the moratorium ? Value taken from the corresponding page of Wikipedia (the mean value for intervals) and not from the IWC page |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

† : The information is based on statistics from the International Whaling Commission and only includes whaling of selected species by the members of the Whaling Agreement. Not taken into account is e.g. B. the pilot whale catch in the Faroe Islands. (17,650 animals in the period 1987-2002 Grindadráp )

2006 indicated a change of heart in the International Whaling Commission. At the instigation of Japan, at the IWC meeting, a narrow majority passed a declaration in which the continuation of the moratorium is described as unnecessary. Environmentalists saw this statement as a major setback. However, this resolution did not mean the lifting of the whaling ban, as a three-quarters majority in the IWC is necessary for this.

At the 59th annual meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in Anchorage on May 31, 2007, a resolution that would have lifted the moratorium was rejected by 4:37 votes; the whaling ban remained in place. Japan, which, like Iceland, calls its whale catches scientific, threatened to leave the commission. Ultimately, the new IWC members Cyprus , Greece , Croatia , Slovenia and Ecuador were decisive for the clear voting result.

Apart from the IWC, there have been other international institutions for some time now that have been trying to protect whales. Examples of this are the Agreement for the Conservation of Small Whales in the North and Baltic Seas ( Ascobans ) and the Agreement for the Protection of the Whales of the Black Sea, the Mediterranean Sea and the Adjacent Atlantic Zones ( ACCOBAMS ).

At the end of 2018 it was announced that Japan would withdraw from the International Whaling Commission on June 30, 2019 .

Whaling by Country

German whaling

German whaling began in Hamburg in 1644. In 1671 the ship barber Friederich Martens reported on a trip to Spitzberg and Greenland , his description was printed in Hamburg in 1675 and translated into various European national languages by 1712. In 1675 already 75 Hamburg ships went on a Greenland voyage , mainly in the waters near Spitsbergen. To this day there is a bay of Hamburg in the northwest of Spitsbergen . After Hamburg, the neighboring local rival Altona , which at that time belonged to Denmark , began building a fleet. The first ship started from the small Elbort Glückstadt in 1671. In 1685 the first Greenland company was founded in Altona. Benefiting from Danish bonuses and privileges, this fleet flourished and reached its peak around 1770. It was not until the English continental blockade during the Napoleonic Wars that it was seriously damaged and could not recover. After 1815, smaller towns with access to the Elbe ( Itzehoe , Brunsbüttel , Elmshorn an der Krückau , Uetersen ) began to equip their own ships. However, their efforts, as well as those from the larger regions, remained sporadic and could no longer reach the pre-war level.

About 40 to 50 people worked on the average whaler. The ships carried six to seven sloops , each manned by six sailors. Some people not directly involved in the catch came to the sloops : cook, cabin boy, helmsman, barber. The latter acted as a so-called "ship's doctor", although his medical qualifications remained doubtful in many cases. Due to the size of the crew, the individual sailors did far less work than on a merchant ship. The real work only began when the hunt started. The ship's captain was usually also registered as a harpooner . The other officers were the helmsman, the bacon cutter, the bacon cutter , the boatswain, the carpenter, the Oberküper and the Schiemann responsible for stowing the bacon barrels.

In particular on the North Frisian Islands , especially Föhr , a large part of the male population initially worked on whalers and thus achieved in some cases considerable prosperity, such as the Föhr captain famous as " Happy Matthias ". This relationship later shifted. The Danish citizens of the time were banned from hiring on foreign ships. After that, more seamen came from the Elbe marshes . In addition, the yields and thus the wages of seafarers fell throughout the 19th century. The qualified North Frisians switched to merchant shipping, while the whalers from the Lower Elbe were often farm workers who secured a sideline as seasonal workers in early summer, the poorest time in agriculture.

The whaling operated from Germany in the 19th century was not particularly effective; instead of whales, seals were mainly caught. The ship "Flora" from Elmshorn, manned by over 50 men, brought 650 seal skins back from its months-long fishing trip in July 1817 , which proved to be difficult to sell. 50 tons of oil were obtained from the bacon of these seals, which had now largely rotted and cooked on land. On the other hand, the ship had loaded around 90 tonnes of food of the most varied variety on departure, including items that were outstanding culinary for the time, such as mustard, butter, coffee, soup cabbage, beer, brandy, syrup, etc.

The Elmshorn ship "Stadt Altona" returned in August 1862 with bacon and skins from 1500 seals, 2 whales and 3 polar bears. The last whale driver from the cities of the Lower Elbe started from Elmshorn in 1872.

Given the imbalance of input and yield, one can assume that there was no massive economic interest behind the German whaling of the time. In view of the comparatively large number of crews and their good supply, it must also be considered whether these activities were more of a kind of hunting excursion out of monotonous rural life, which also contributed to the increase of the team's reputation.

Attempts at a new beginning from 1900

After the increasing German demand for whale oil could be met by Norway for decades, there was a first German attempt to participate in the whaling business again in 1903. The shipping company Germania Walfang- und Fischindustrie A.-G. in Hamburg, in which the shipping company Knöhr & Burchard was involved, went whaling with two fishing steamers off Iceland, but soon gave up the company due to low profitability. 1913-14 made the German-South West African whaling A.-G. made a new attempt and operated whaling from Walvis Bay, which however had to be stopped due to the war. The shortage of foreign exchange after the First World War meant that Germany, as the main buyer of whale oil (in 1930 over 170,000 tons of oil was imported for over 90 million marks), started thinking about going into whaling.

German whaling in the 1930s

At that time, the Norwegian state, as the world's largest producer of whale oil, wanted to prevent foreign competition through regulations, which led to a sharp rise in prices as demand grew worldwide. The Norwegian whaling law of the time forbade the sale or rental of specific whaling equipment and the so-called “crew paragraf” forbade Norwegians to hire foreign whalers. However, Germany's trade pressure grew ever stronger and Norway was ultimately unable to prevent German whaling. Nevertheless, the share of Norwegian crew members on the four German whaling expeditions was initially almost 39%, but fell to around 27% in the following season. The large proportion of Norwegians is due to the fact that there was high unemployment in Norway in the 1930s and the working conditions in the German whaling shipping companies were better. Norway did not succeed in preventing the construction of German whaling ships. From 1937 three Norwegian expeditions and from 1938 one British expeditions for Germany were whaling. In this way Norway lost its most important buyer of whale oil in a short period of time. Between 1938 and 1939 a total of seven factory ships with 56 fishing boats caught for Germany, which made it the third largest whaling nation.

The two captains Otto Kraul and Carl Kircheiß and the entrepreneur Walter Rau were among the pioneers of German whaling after the First World War . Otto Kraul was one of the few Germans who had experience with modern whaling. He had been a shooter and a fan leader in Argentina and South Georgia . Later he worked for a Soviet whaling company before he got the order from Germany to lead the first expedition to Antarctica with the " Jan Wellem ". This was initiated by the Erste Deutsche Walfang-Gesellschaft mbH .

During the First World War, Carl Kircheiß was a lieutenant on the German auxiliary cruiser SMS Seeadler under the command of Felix Graf von Luckner . Around 1931 he took part in several trips to Antarctica and the west coast of America and worked on a Norwegian whaling ship. He campaigned for German whaling in numerous lectures and got a leading position in the First German Whaling Society in 1935 . The plans for their own German whaling took shape in March 1935 when Walter Rau Walfang AG was founded on March 5, and the Erste Deutsche Walfang-Gesellschaft mbH in Wesermünde on March 25, 1935.

There are five reasons argued for a private German whaling: First and foremost was the self-sufficiency efforts of the Nazis , the high dependence on imports from Norway to reduce and at the same time a considerable cost-saving potential due to reduced foreign exchange used to implement and bypassing the Norwegian price increase. In addition, it was possible to expand production volumes and reduce unemployment. Own whaling therefore became an important project in the second German four-year plan 1937-40 to close the so-called fat gap .

With the establishment of Walter Rau Walfang AG by the Lower Saxony oil mill owner Walter Rau, he wanted to expand his value chain. With the support of the German government, he had the whaling mother ship Walter Rau built with initially eight fishing vessels ( Rau I to Rau VIII ) at the Deutsche Werft in Hamburg.

The Walter Rau was then the world's best-equipped factory ship, which first leaked in the season 1937-38 for a catch in the Antarctic. After the Second World War, the war-damaged ship was repaired and modernized and then went to Norway as a war refund in 1948. It was taken over by "Kosmos A / S" and renamed Kosmos IV . She became the last and only Norwegian factory ship to have whaled in Antarctica during the last Norwegian fishing season, 1967-68. The ship was later sold to Japan.

The fishing boat Rau IX , built in 1939 at Deschimag , shipyard Seebeck Bremerhaven, is today after more than 30 years of service - first in the war as a submarine hunter, outpost boat and mine clearer, then as a whaler in Norway and Iceland - the museum ship of the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven . It is particularly noteworthy that the ship today represents the condition as a German whaling ship, which it should originally have, but never actually had, since the ship was converted into an auxiliary warship before its first use as a whaling boat.

The whaling factory ship Unitas was built in 1936-37 for the "German Whaling Society Hamburg" at AG Weser in Bremen. Its tonnage of 21,845 gross tons made it the world's largest before the war. The Unitas I-VIII fishing boats were copies of English boats. In 1945 the Unitas was handed over to England as a war restitution and renamed Empire Victory . The ship was later sold to the "Union Whaling Company" in South Africa and renamed Abraham Larsen (1950–57); In 1957 she went to Japan and was named Nisshin Maru .

In the 1936–37 season, the Norwegian factory ships CA Larsen and Skytteren caught only on German account for the first time. The German margarine industry founded the “Margarine Rohstoff Beschaffungsgesellschaft” (MRBG) and entered into a partnership with the two Norwegian whaling companies. The Germans owned 40% of the shares in the companies "A / S Blaahval" and "A / S Finhval", which CA Larsen and Skytteren operated.

In 1937 the German "Ölmühlen Rohstoff GmbH" in Berlin acquired the Norwegian factory ship Sydis and renamed it the Südmeer . A year later the "Ölmühlen Whaling Consortium" bought the factory ship Vikingen , built in England, and named it Vikings . Carl Kircheiss was a captain on the Viking for 90 days in 1939 .

The use of four cooking plants, namely CA Larsen , Skytteren , Südmeer and Wikinger , was coordinated by the "Hamburger Walfang-Kontor GmbH". The cookery Jan Wellem , CA Larsen and Skytteren started three seasons for German shipping companies (1936–37 to 1938–39); Walter Rau , Unitas and Südmeer caught for Germany in the seasons 1937–38 and 1938–39; the Vikings only in the 1938–39 season.

In the spring of 1939, the independent German whaling ended. A total of seven German fishing fleets had sailed into the Arctic and Antarctic and hunted around 15,000 animals. The German whaling fleet was rebuilt and for use by the Navy defense technically equipped.

1950s and 1960s

Former employees of the Reich Office of Cetacean Research accompanied in the early 1950s trip for manned by over 600 German sailors, under the flag of Panama propelled whaling ship Olympic Challenger of Aristotle Onassis , to examine the possibilities of a German re-entry into the whaling. Onassis' whaling expeditions attracted worldwide attention because they hunted whales without regard to international agreements, catch quotas, minimum animal sizes and fishing areas. The English, Japanese and Russians probably did the same. But when Onassis threatened to monopolize the oil transport from Saudi Arabia to the USA in 1954, German crew members were bribed with large sums of money by the CIA in order to document the massive violations of the rules during whaling with photos and films and thus obtain a pretext to transport Onassis' whale oil loads To confiscate Hamburg and Rotterdam and to chain the transport ships. Senior executives of the First German Whaling Society, including Dietrich Menke , who were hoping to get back into the business, as well as the Norwegian Whaling Association, Norwegian trade unions and the Peruvian government participated in these operations, which were supposed to harm Onassis wherever possible . Peru even brought its fishing vessels within their territorial waters, which were unilaterally extended to 200 nautical miles with the tolerance of the USA. Onassis then gave up whaling. The First German Whaling Society was dissolved in 1956.

At the beginning of the 1960s, a small number of German whalers worked for the last time on the Dutch fishing ship Willem Barendsz .

Norway

Norway has reserved against the moratorium and therefore describes itself as not bound by the instruction. The country stopped whaling to study the stocks between 1988 and 1993. Since then, Norway has been catching several hundred minke whales annually, with the Norwegian government setting certain catch quotas. In 2005 the quota was 769 whales and 639 animals were shot. Since the quota is made up of the quota of the previous year and the difference between the quota and the actual catch of the two previous years, the quota for 2006 rose to 1052 animals.

Whaling only plays an economic role in a few regions. Average consumption in Norway is also low. The ideological component is more important: whaling has broad support among the population and, as long as it is about the abundant minke whales, is mostly advocated. 736 minke whales were killed in 2014. For 2017 the catch quota was increased from 880 (2016) to 999 minke whales and for 2018 again to 1278 animals.

Japan

In Japan, the Institute of Cetacean Research claims that minke whales are hunted for scientific purposes, which animal welfare organizations use as a pretext for commercial whaling. The whale meat is then sold in accordance with the regulations for the greatest possible utilization; however, the demand for whale meat in Japan is low and declining. The stored whale meat rose from 1,453 t in 1999 to 5,093 t in December 2010. Estimates by the WWF assume that the Japanese state subsidizes whaling with more than 10 million dollars annually.

In November 2007, despite international protests, Japan released the whaling fleet Nisshin Maru with five escort ships to the Antarctic with a quota of over 900 whales, including 850 minke whales ( not endangered ) and 50 fin and humpback whales each (of which fin whale endangered) , according to the news agency Kyodo News. . A month later, in response to fierce international protests, Japan announced that it would suspend the humpback whale hunt while talks about reforming the IWC continued. In fact, the fleet hunted 551 minke whales in the 2007/2008 season, 679 minke whales and one fin whale in 2008/2009 and 506 minke whales and one fin whale in 2009/2010. The fleet remained below the self-planned quota due to the persecution by the environmental protection organization Sea Shepherd .

On the occasion of a trial against two Greenpeace activists in Japan in March 2010, the new Japanese government signaled that it was looking for a compromise in the whaling dispute and was proposing the following arrangement: Japan abandons whaling in distant seas (especially expeditions to the South Pacific) on, the international community tolerates that Japan hunt whales to a limited extent on its own coasts - as it is practiced in Norway.

In 2011 the Japanese whaling expedition to the South Pacific was prematurely canceled due to the actions of the American organization Sea Shepherd . Instead of the planned 850, only 170 whales were killed.

On March 31, 2014, the International Court of Justice in The Hague prohibited the Japanese government from continuing to hunt in Antarctica. The reason given by the court was that whaling does not serve science, but only the sale of whale meat for consumption. Instead, Japan is now continuing whaling (to a lesser extent) in the North Pacific.

Japan presented a revised plan in November 2014. A panel of experts from the International Whaling Commission (IWC) described the scientific whaling program as not convincing in April 2015.

According to the IWC, 462 minke whales and 134 sei whales were killed in 2017. In 2018, 333 minke whales, 122 of them pregnant , were killed.

At the end of 2018, it was announced that Japan would withdraw from the International Whaling Commission on June 30, 2019 and resume commercial whaling. The Japanese Ministry of Agriculture then set the following catch quotas for 2019: 52 minke whales, 150 Bryde's whales and 25 sei whales. Japan wants to limit hunting to its own territorial waters in the future.

Faroe Islands

An old tradition in the Faroe Islands (49,179 inhabitants in 2015) is pilot whale fishing for personal use.

In 2013, 1,104 pilot whales and 430 white-sided dolphins were shot.

Iceland

In Iceland, whales hunted and meat started again in 2003. Conservationists are protesting against it, as are tourism companies , who fear that the whales will be shy and whale watching will no longer be possible.

In 2006 Iceland decided to re-allow commercial whaling in addition to its scientific whaling. 30 minke whales and 9 fin whales were allowed to be caught off the coasts despite protests.

In 2014 137 fin whales and 24 minke whales were killed. In the following year 155 fin whales.

In February 2016, Icelandic fishing entrepreneur Kristjan Loftsson announced that it would not catch fin whales this year. In an interview with an Icelandic newspaper, the only fin whale hunter in Iceland justified his decision with the strict controls in the sales market of Japan. The species protection organization Pro Wildlife , however, sees another reason that the business has become unprofitable for the entrepreneur because the transhipment ports in the EU have been refusing stopovers for whale meat transports since 2014. That is why Loftsson has to ship the meat via the Arctic route - that takes much longer and increases the costs.

United States

In the United States , only the Makah Indians in Washington state still catch whales today. The tribe are regularly given catch quotas by the IWC.

Eskimo

The Eskimo culture is still a relatively uniform hunter culture , which until the middle of the 20th century was mainly based on hunting marine mammals ( seals , walruses , whales ), but also land animals ( caribou , polar bears ). In Alaska, whale hunting is still a component of subsistence farming today . The most important hunting weapon is the harpoon, the hunt is done from kayaks , whereby the harpoons were provided with a long line and buoyant bladders. The whale used to be harpooned with as many harpoons as possible until it was exhausted enough to be able to reach it in the kayak and deal the fatal blow.

South Korea

The resumption of “scientific whaling” from 2013, announced in June 2012, led to worldwide protests. The application deadline, which ran until December 3, 2012, let South Korea pass due to these protests, so that South Korea was not involved in whaling in 2013.

Russia and Soviet Union

Whaling by the Soviet Union played a special role after World War II and escalated in the early 1960s. It was not until the 1990s that it became known that the Soviet Union had systematically reported incorrect figures for the statistics of the International Whaling Commission. According to current assumptions, around 180,000 more whales were shot by the Soviet fishing fleets than according to the official figures. The Soviet Union is almost solely responsible for the collapse of the humpback whale population in the waters around Australia. It is astonishing that the whales were hardly used except for the fat. The planned economy provided for constantly increasing income in each sector, so hunting was carried out even if there was no economic benefit to be drawn from it.

In 2018 it became known that around 100 whales were held captive in small pools in the sea near Nakhodka in the far east of Russia. Companies had been allowed by the authorities to catch whales for educational purposes. Whales were sold to Chinese marine parks. In April 2019, following protests, it was agreed that the whales would be released back into the wild.

Equatorial Guinea

Under the influence of American whaling practice, the population of the island of Annobón began to hunt humpback whale calves from canoes with harpoons and spears in the second half of the 19th century. The meat served the self-sufficiency , the hunting itself not least as a status act. After the operations of modern factory ships in the surrounding sea area had led to a drastic decline in the humpback whale population in the 1950s, Annobonese could hardly find any more calves. It is unclear whether the Indonesian whaling continued through the 1970s and is possibly practiced to this day due to the repressive dictatorship and information control in Equatorial Guinea.

Similar to the case of Annobón, the population of Bioko also adopted American whaling practice at times.

Hunted whales

Sperm whale : an average of 17 meters long and weighs around 60 tons . The male sperm whale is almost twice the size of the female. Because of its seemingly infinite number at the beginning of the 19th century (possibly around 1.5 million copies), it was of the greatest economic importance during this period. One animal produced up to 7000 liters of oil, which was processed into high-quality technical oils, as well as whale rat and ambergris. This made it one of the most sought-after species.

Bowhead whale : The whale , which is up to 17 meters long and weighs 85 tons and is native to the Arctic, has, in addition to the longest whale, a layer of fat about 50 cm. Because the beards were so valuable, the whalers often disposed of the carcasses without slimming them. The bowhead whale is very slow and was therefore a very welcome prey, especially in the early days of whaling.

Southern right whale , northern right whale: Its English name is "right whale" because it is very lazy and swims on the surface when it is dead. It has a layer of fat up to 40 cm thick and beards up to two and a half meters long. In addition, with a weight of up to 50 tons, it delivers a relatively large amount of meat and was therefore easy and rewarding prey.

Humpback whale : The humpback whale is up to 13 meters long and weighs up to 35 tons. It has a layer of bacon up to 65 cm thick and was widespread in the coastal areas. It was not very popular with the whalers because it usually went down after being killed.

Sei whales belong to the baleen whales (Mysticeti), which are characterized by 600 to 680 whales instead of teeth in their mouths. They reach an average length of 12–16 meters and a weight of around 20–30 tons. The largest animals are up to 20 meters long and weigh 45 tons.

Fin whales were not very attractive as prey until the beginning of the 20th century due to their high speed. However, after the blue whale population declined, they were also heavily hunted to replace them.

The blue whale can reach up to 33.5 meters in length and weigh up to 200 tons. An animal that was 27 meters long and weighed 122 tons was cut up and weighed. This resulted in the following individual weights:

| Parts | Mass in kg | Share of the total mass in % | Oil yield in kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| meat | 56,440 | 46.3 | 6,900 |

| bacon | 25,650 | 21.0 | 13,600 |

| bone | 22,280 | 18.3 | 7,200 |

| tongue | 3,160 | 2.6 | |

| lung | 1,230 | 1.1 | |

| heart | 630 | 0.5 | |

| Kidneys | 550 | 0.4 | |

| stomach | 410 | 0.3 | |

| liver | 940 | 0.8 | |

| guts | 1,560 | 1.3 | |

| Beards | 1,150 | 0.9 | |

| Blood approx. | 8,000 | 6.5 | |

| total | 122,000 | 100 | 27,700 |

fleet

A classic whaling convoy sits down i. d. Usually made up of at least two types of ships or boats. There is a mother ship (which is usually the factory ship at the same time ), as well as several, mostly smaller fishing and harpoon boats that hunt down the whale. In the case of particularly large or modern fleet units, it is not uncommon for them to be accompanied by supply ships and scout ships (which go ahead of the actual unit in order to spot the whales early on).

The hunt

Using the example of a blue whale hunt: As soon as a whale is sighted (indicated by the call "He blows" from the lookout), the fishing boat sets course for the whale with extreme force. At a distance of about one kilometer, it reduces its speed to slow travel. Meanwhile, the harpooner studies the animal's peculiarities. There are curious whales. They are given the opportunity to satisfy their curiosity until, with a little help from the helmsman , they get in front of the bow of the fishing boat. As long as they are not disturbed, adult whales show a considerable consistency in their breathing rhythm and thus in their emergence. The breath jet, known as the “ blow ”, consists of air that condenses when the outside temperature is low - and becomes visible as mist. From the number of bubbles rising, the harpooner can determine the duration of the swim under water and the presumed point of their surfacing. Whalers speak of an “eight-minute whale” or a “nine-minute whale”. In distress, whales can hold their breath considerably longer, up to half an hour, and sperm whales up to an hour. However, greater efforts force them to emerge more frequently. If a blue whale stays under water for an unusually long time and if it comes up every time from 500 to 1000 meters from the fishing boat, it is usually an older animal that has been hunted more often. Blue whales that feel chased become restless. The animal then moves away from the fishing boat with changing pace and changes of direction. When and where it will appear cannot be foreseen. During the pursuit, the fishing boats run through the entire speed range from extreme power ahead to very slow speed. The fishing boats must come at least 20 meters from the whale in order to be able to use the harpoon correctly. Patient sneaking is therefore the widespread hunting tactic. This art is - if at all - very difficult to learn and far more important than throwing the harpoon. It is the result of years of experience and empathy for the individual behavior of the whale. The harpooner has to know about the current conditions on site, the behavior of groups of two or three and the tactics of experienced loners.

Harpoons

In the picture from top to bottom: The double-bladed harpoon or bartharpune belonged to the standard equipment of the whalers until around 1840 the single-bladed, which penetrates deeper and falls less easily. The Spannagel, invented in 1848, brought a further improvement. It penetrates like a needle and interlocks with a barbed hook that is positioned transversely. The whale is dealt the fatal blow with the thrust lance. The spiked pistol, which has been in use since 1860, contains an explosive charge that fires a second arrow.

Course of the flushing

A hunted whale was with the head aft on the starboard side secured with a heavy chain. A scaffold, the Flensstelling , was lowered and positioned over the whale. The Flensers stood on this scaffolding to remove the bacon. The tools used were bacon knives, fish hooks, pikes, bacon hooks and bacon forks up to six meters long. By driving lightly under reduced sails, the whale was pressed close to the ship's side due to the current of the water.

A sailor with a monkey tampon jumped onto the whale to attach a hook. The first piece of deck that the Flenser peeled off was hoisted up on this hook .

Standing on the Flensstelling, the Flensians separated the toothed lower jaw from the whale. To do this, the whale was turned on its back beforehand. The backbone of the whale was then severed. This piece was then allowed to sink astern until the sailors finished losing weight. After the heads of sperm whales had been cut off, they were hoisted up to the level of the deck in order to skim the so-called whale rat from the cranial cavity .

While the last piece of deck was being hoisted up, the Flensians used knives to search deep inside the whale for amber , a substance that sometimes settles in the whale's intestines and was worth more than its weight in gold . Amber was valued in perfume making, it is only found in sperm whales. It was so rare that little more than a ton of it were found between 1836 and 1880.

Below deck, the deck pieces were separated into smaller parts, the so-called Vinken . Then the Vinken were cut into thin slices (Bible leaves), which then melted particularly quickly in the potion kettles.

Whalers' logs

Boredom and disappointment were part of the whaler's daily bread and nowhere were the feelings more clearly expressed than in the logbooks of the whalers. These logbooks were traditionally decorated with pictures of whales, which were entered with self-made stamps . On the whalers it was the duty of the first helmsman to keep the logbook. The helmsman of the William Baker stamped a whale upside down in the logbook on November 21, 1838, describing that the crew had sighted several northern right whales. Next to the whale he wrote “SBB 55 bbs” - starboard bow boat, 55 barrels of oil - and also painted how the whale was harpooned. The other stamps and entries report a long streak of bad luck. The stamp showing half a whale with its fluke facing up means the whale was hunted but escaped. A whale head meant the whale was harpooned but escaped. Under November 24th, he draws an entire whale upside down, meaning that the whale was killed but sank before it could be moored to the ship. The long-snouted animals are bottlenose dolphins that were hunted for food. On November 28, a harpooned whale smashed a fishing boat.

Many whalers had a set of stamps made of wood or whale bone, depicting whales, porpoises, pilot whales and turtles in a stylized form .

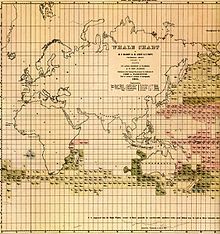

The United States Navy wanted to look into the logbooks of the whalers for information about the winds and currents . In order to obtain this information, the American naval officer Matthew Fontaine Maury had to promise the whalers that he would draw up a nautical chart showing all the whales that were sighted. This nautical chart was published in 1851.

Fishing areas

Greenland trip

In 1596 the Dutchman Willem Barents discovered the Spitzbergen archipelago and thus a hunting area with numerous seals, whales and other animals. Fifteen years later, the English and Dutch set up the first stations on Svalbard, which they believed to be eastern Greenland at the time. Coastal whaling was carried out from these stations and this type of hunt was called baien fishing and the trips made there were called Greenland Voyage . At that time the bowhead whale (nickname: gold mines of the north ) was mainly hunted . During the heyday of the Greenland Voyage, the total annual prey from all ships involved was 1,500 to 2,000 whales. Between 1770 and 1779, these were shared by an average of 130 Dutch, 70 English and 45 German ships. Hamburg reached its highest participation in 1675 with 83 ships, Bremen in 1723 with 25, Altona in 1769 with 18, Glückstadt in 1818 with 17, Emden in 1660 with 15 and Flensburg in 1847 with 9 ships.

Mudhole whaling

The life cycle of the gray whale was barely disrupted until the mid-19th century, as a gray whale supplies much less oil than a sperm whale or bowhead whale. The gray whales were only hunted by Eskimos and Indians along their migration routes . The first attempts to hunt the gray whale were made in easily accessible lagoons , e.g. B. in the Bahia Magdalena , which is in the southern part of the Baja California peninsula . The whalers found that a cornered gray whale could fight even wilder and more dangerous than a sperm whale. The gray whales are characterized by vigilance and cunning, as well as the ability to use the shallows of the lagoons to their advantage. This type of whaling was nicknamed Mud Hole Whaling , and the gray whale earned the nickname Devil's Whale due to its fighting spirit .

Contemporary witnesses: Testimony of a helmsman to his captain, recorded in the captain's logbook: I went to sea to become a whaler. I did not imagine that I would be sent into a duck pond to hunt pool hyenas. Say what you want, captain, these critters ain't whales at all . What kind of animals, in his opinion, the captain wanted to know. So if you ask me, these are crossbreeds between sea snakes and crocodiles.

Excerpt from the logbook of the whaler Boston after the gray whale hunt: Two boats were completely destroyed, while other fishing boats were hit up to 15 times in different places. Of the 18 men who commanded and manned them, six were beaten, one broken both legs, another three ribs, and another was so badly injured inside that he would be unable to serve for the rest of his life. All of these accidents happened before we had killed a single whale.

Whale hunting along the East Pacific coast

On their annual migration, the gray whales came along the California coast , so that some whalers stalked them there in the 19th century. A former captain named JP Davenport built the first California coastal station with cookery and warehouses in Monterey in 1854 . Davenport and his people were soon producing 1,000 barrels of oil a year. At the end of the 1860s there were 16 whaling stations on the Pacific coast , from Half Moon Bay near San Francisco down to Baja California. The companies , as they were called, each included a captain, a helmsman, two harpooners and a dozen sailors as a crew for two fishing boats.

With a harpoon rifle for the first shot at the whale and with a bomb lance to kill the whale, the teams of the fishing boats usually had an easy time. They dragged the carcass ashore. Since these stations did not require a lot of effort - such as an equipped whaling ship - they initially achieved exceptionally high profits. Some stations landed 25 whales annually, which was roughly the yield of a whaling ship. In the first 22 years of its existence, these whaling stations hunted 2160 gray whales and 800 humpback whales and other whales.

Coastal whaling also posed problems. Sometimes the fishing boats had to travel up to 10 nautical miles to find the migrating whale herds. In doing so, they were unable to bring the whales that had been shot ashore. Around 20 percent of the whales hunted by the coastal crews were lost because of bad weather or the whales drowned while being towed ashore. The heyday of these stations lasted only 30 years. During this time, the stations decimated the population of California gray whales.

A well-known historic whaling monument on Vancouver Island , Canada is the Yuquot Whale Shrine , currently located in New York. He recalls that whaling had a very high cultural significance there, because of the basic food supply for all, and because the role of the catch divided society as a whole, in particular the chief and his clan were highlighted. There the catch was accompanied before and after by ceremonies that could not be missing.

Grindadráp

The Grindadráp is the practice of catching pilot whales in the Faroe Islands. For most Faroese it is part of their history and a matter of course for obtaining food on a subsistence basis with strong legal regulations.

Nantucket

Nantucket is an approximately 90 km² island south of Cape Cod off the northeast coast of the USA. At the same time, it also forms Nantucket County in Massachusetts . The town and island of the same name were best known for the whaling that began there in the 18th century.

Before its discovery in 1602 by the English captain Bartholomew Gosnold, around 3000 people of the Indian tribe of the Wampanoag populated the island.

1641 was taken over by Thomas Mayhew , who grazed sheep on Nantucket until 1659.

After the washed-up carcasses of whales had previously been processed into oil, the hunt for whales with small boats near the coast began around 1690. After whale hunting and its value had been discovered in the heads of sperm whales, whale hunting was extended to the high seas from 1715 .

The typical Nantucketer whaling voyage towards the end of the 18th century, which largely specialized in sperm whales, led from the North Atlantic around Cape Horn into the Pacific to the Japanese coast and lasted two to four years.

Since then, the island's economy has increasingly turned to the trade in oil and whale rat, as well as the construction and maintenance of whaling ships and their crews. The city of Nantucket experienced an enormous economic boom and was the “whaling capital” of the world from the early 18th century to around 1830.

Worldwide oil discoveries from 1830 onwards impaired sales of Tran as a lubricant and lamp fuel and ushered in the decline of the Nantucket economy. This was accelerated by longer and longer fishing trips through empty seas. The well-known “Nantucket shallows” in front of the port also hindered the growing whaling ships, which therefore switched to the neighboring ports of New Bedford and Salem (Massachusetts) with their direct rail connections.

Nantucket is now a seaside resort and resort .

The authors Edgar Allan Poe set monuments to whaling in Nantucket in his novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and Herman Melville in Moby-Dick .

Classification of the Antarctic fishing areas

From the end of spring to autumn, the waters are populated in very different densities by whales grazing krill .

The Southern Arctic Ocean is divided into six fishing areas.

Fishing area I covers part of the southern Pacific from 90 ° west to 60 ° west. However, within this area whaling was only practiced in a relatively small area around the South Shetland Islands .

Fishing area II denotes the Weddell Sea from 60 ° west to 0 °. The hunted here was mostly around Bouvet Island and the southern Sandwich Islands . In the Weddel Sea, whales and krill are rare because of the cold water.

Fishing area III adjoins the Bouvet Islands and extends to 70 ° East to the Kerguelen . The catch begins in the Bouvet Islands and over the course of the summer follows the retreating ice edge eastward to the area of Enderby Land .

Fishing area IV extends from 70 ° to 130 ° east. The hunt begins at the Kerguelen and leads along the ice edge between the lands 90 ° to 110 ° east.

The fishing area V covers the area from 130 ° East to 170 ° West and thus a large part of the Ross Sea . This area was too remote for the European fishing fleets, so that mainly Japanese and Russian fishing fleets stayed here, as the journey is shorter for them. The hunted here was around the Balleny Islands up to 160 ° East.

The fishing area VI corresponds to the Pacific area of the southern Arctic Ocean and extends from 170 ° to 90 ° west.

With seven fishing stations used in the 20th century, South Georgia developed into the center of whaling in the Antarctic, although its importance declined significantly after the introduction of the whaling flotilla with its floating boilers.

The southernmost whaling station ever used was on Deception Island .

Celebrities

Ships

- The Lagoda of the New Bedford whaling shipping company is considered to be the most successful whaling ship of its time .

- The Essex (1820) of Nantucket is the most popular case of an attacked by a whale and recessed whaler.

- The Charles W. Morgan , built in 1841, is the only surviving wooden whaling sailing ship of its time in the world. It is laid up in the museum harbor of Mystic Seaport .

persons

- The future Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter drove as a young helmsman on several trips on the whaler De Groene Leeuw to Greenland and Svalbard. He later owned a whaling ship himself.

- George Pollard , skipper of the Essex , which was rammed and sunk by a whale in 1820 , lost again two years later as skipper of the whaler Two Brothers by stranding on a reef off Hawaii .

Single whale

- Mocha Dick was a male sperm whale with skin more gray than brown and a white scar on his enormous head. It owes its name to his first meeting with whalers around 1810 near the island of Mocha off the Chilean coast. Herman Melvilleimmortalizedhim as Moby Dick . But even in reality, Mocha Dick was never caught by the Nantucket whalers (a Swedish whaler allegedly shot him in 1859), despite the international press attacking him along with other big white males such as Spotted Tom , Shy Jack , Ugly Jim and Fighting Joe had qualified as "Terrorists of the Sea" and had high bounties on them. The following “irreplaceable” whales became known: Don Miguel , Morquan , Timor Jack “... who knows how an iceberg is ...”, Ugly Jack and New Zealand Tom .

Representations of whaling

Motive in literature

The most famous literary portrayal of whaling is Herman Melville's Moby Dick , in which the possessed Captain Ahab tries to hunt down a white sperm whale that tore off his leg years earlier. Hammond Innes

tells another story about whaling in The White South (1949, German by Arno Schmidt under the title The White South ).

A whaling trip on a panorama

As the forerunner of cinema, panorama was a widespread way of depicting historical events and distant lands. The images were on a huge roll of canvas that was unrolled scene after scene on a stage while a narrator explained the plot. Famous panoramas were e.g. B. The Battle of Gettysburg and the Fire of Moscow . However, the whaling epic produced by the Purrington & Russels company was unsurpassed . Benjamin Russel, who had learned to paint as an autodidact, boarded the whaler Kutusoff in 1841 and spent three years sketching for his whaling saga . At home he hired the house painter Caleb Purrington to transfer the opus onto canvas. After completion, this panorama was 400 meters long. “One can say without transposition,” the historian Samuel Eliot Morison later wrote, “that it is a pictorial counterpart to Herman Melville's classic Moby Dick ”.

See also

- fishing

- Whale explosion

- International Convention on the Regulation of Whaling

- List of the German whaling fleet

- Hunting season - on the trail of the whalers , documentary about a Greenpeace mission to prevent whaling by the Japanese whaling fleet

- Kvalvågstraumen whaling site

- Whaling station

- Whaling Station on Griffiths Island

- Whaling boat

- Whaling off Iceland

- Soon May the Wellerman Come (whaling section in New Zealand)

- Whaling off Norfolk Island

- Whaling in Norway

- Whaling in Tasmania

literature

Bibliography:

- Herman Melville : Moby-Dick; or: the whale . German by Friedhelm Rathjen . Edited by Norbert Wehr . Attached is an essay by Jean-Pierre Lefebvre on "The work of the whale" . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 2011. ISBN 978-3-86150-969-1 .

- Hammond Innes : The White South. 1949. (German by Arno Schmidt under the title The White South )

- Whaling duel in the Caribbean. In: Geo . 1/1977, pp. 94-109.

Technical literature:

- Wanda Oesau: Schleswig-Holstein's Greenland trip to catch whales and seal seals from the 17th to 19th centuries. JJ Augustin , Glückstadt / Hamburg / New York 1937.

- Wanda Oesau: Hamburg's Greenland trip to catch whales and seal seals from the 17th to 19th centuries. JJ Augustin, Glückstadt / Hamburg / New York 1955.

- Wanda Oesau: The German South Sea fishing for whales in the 19th century. JJ Augustin, Glückstadt / Hamburg / New York 1939.

- Eugen Drewermann: Moby Dick or From the monster to be human. Walter Verlag, Düsseldorf / Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-530-17010-0 .

- Tim Severin: The white god of the seas. In search of the legendary Moby Dick. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-352-00630-X .

-

Nathaniel Philbrick : In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex . Penguin, New York City 2000, ISBN 0-14-100182-8 .

- German by Andrea Kann and Klaus Fritz : In the heart of the sea. The Whaler's Last Voyage Essex . Karl Blessing Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-89667-093-X .

- Owen Chase : The Fall of Essex (1821). Piper, Zurich / Munich 2002, ISBN 3-492-23514-X .

- Thomas Nickerson, Owen Chase, Nathaniel Philbrick, Thomas Philbrick: The Loss of the Ship Essex, Sunk by a Whale. Penguin, New York 2000, ISBN 0-14-043796-7 .

- Richard Ellis: Man and Whale. The story of an unequal struggle. Droemer Knaur, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-426-26643-1 .

- Berend Harke Feddersen: The historic whaling of the North Frisians. Husum Printing and Publishing Company, Husum 1991, ISBN 3-88042-578-7 .

- Emil G. Bai: Fall, Fall, Fall, öwerall! Report on Schleswig-Holstein whaling. Egon Heinemann Verlag, Hamburg Garstedt 1968.

- Robert McNally: So remorseless a havoc: of dolphins, whales and men. Little, Brown, Boston 1981, ISBN 0-316-56292-0 .

- Farley Mowat: The Fall of Noah's Ark - From the suffering of animals among humans. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1987, ISBN 3-498-04297-1 . (Original edition 1984, Toronto; 4th part about the whale / catch)

- Adam Weir Craig: Whales and the Nantucket Whaling Museum. Nantucket Historical Association. Nantucket 1977.

- Nelson Cole Haley: Whale hunt; the narrative of a voyage by Nelson Cole Haley, harpooner in the ship Charles W, Morgan, 1849-1853. Ives Washburn, New York 1948. (A later edition by the Seaport Museum in Mystic / Connecticut has ISBN 0-913372-52-8 )

- Eric Jay Dolin : Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America . WW Norton, New York City, USA 2010, ISBN 978-0-393-33157-8 .

- Joan Druett: Petticoat Whalers, Whaling Wives at Sea, 1820-1920. University Press of New England, Hanover 2001, ISBN 1-58465-159-8 .

- Joost CA Schokkenbroek: Trying-out: An Anatomy of Dutch Whaling and Sealing in the Nineteenth Century, 1815–1885. Aksant Academic Publishers, Amsterdam 2008, ISBN 978-90-5260-283-7 .

- Johan Nicolay Tønnessen, Arne Odd Johnsen: The history of modern whaling. C. Hurst & Co., London 1982, ISBN 0-905838-23-8 .

- Felix Schürmann: The gray undercurrent. Whalers and coastal societies on the deep beaches of Africa (1770–1920) . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York City 2017, ISBN 978-3-593-50675-3 .

- The Place-Names of Svalbard . Norsk Polarinstitutt , Oslo 1942. (2001, ISBN 82-90307-82-9 ).

- Hanns Landt-Lemmél; Whale free: On whaling in the Southern Arctic Ocean. Eberhard Brockhaus Verlag, Wiesbaden 1950.

- Fats and soaps. 1938, Volume 45, Issue 1, pp. 1-124. (accessed on May 24, 2010)

- Frank Sowa: "What Does a Whale Mean to You?" - Divergence of Perceptions of Whales in Germany, Japan, and Greenland. In: Forum Qualitative Social Research / Forum: Qualitative Social Research. Volume 14, No. 1, January 29, 2013, ISSN 1438-5627 . (on-line)

- Frank Sowa: The construction of indigenousness using the example of international whaling. Greenlandic and Japanese whalers in pursuit of recognition. In: Anthropos. Volume 108, 2, 2013, pp. 445-462.

- Frédéric B. Laugrand, Jarich G. Oosten: "We're Back with Our Ancestors." Inuit Bowhead Whaling in the Canadian Arctic. In: Anthropos. Volume 108, 2, 2013, pp. 431-443.

- Electric harpoon . In: The Gazebo . Issue 47, 1853, pp. 520 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Whaling in ivory. On: Wissenschaft.de of April 2, 2008. Evidence of early whaling.

- International Whaling Commission - IWC (English)

- Website on the comic 'Jonas Blondal' - the subject of whaling with background information

Individual evidence

- ^ Ana SL Rodrigues, Anne Charpentier, Dario Bernal-Casasola and Armelle Gardeisen: Forgotten Mediterranean calving grounds of gray and North Atlantic right whales: evidence from Roman archaeological records. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285 (1882): 20180961 July 2018, DOI: 10.1098 / rspb.2018.0961

- ↑ Melanie Challenger: On Extinction: How We Became Estranged from Nature . Garnet Publications, London 2011, ISBN 978-1-84708-392-0 , p. 106.

- ^ Dennis Meadows (Club of Rome): The Limits to Growth. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1972, p. 138.

- ^ A b Club of Rome, 1972, p. 137.

- ↑ The Secret Life of the Sperm Whales ( Memento of February 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), Das Erste , June 18, 2003.

- ↑ IWC: Catch limits and catches taken, Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling catches since 1985 ( Memento of March 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ IWC: Catch limits and catches taken, Special Permit catches since 1985 ( Memento from February 19, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ IWC: Catch limits and catches taken, Catches under Objection since 1985 ( Memento of July 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ IWC: Whale Population Estimates ( Memento from March 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Pilot whale catches in the Faroe Islands 1900–2000 ( Memento from April 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on whaling.fo

- ↑ Defeat for whaling countries. In: diepresse.com. June 1, 2007.

- ↑ Japan is killing whales again. In: bernerzeitung.ch . December 26, 2018, accessed December 26, 2018 .

- ↑ According to Conway (1906) already used by Hamburg whalers in 1642, see The Place Names of Svalbard , entry Hamburgbukta

- ^ A b Johan Nicolay Tønnessen, Arne Odd Johnsen: The history of modern whaling. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1982, ISBN 0-905838-23-8 , pp. 423 f.

- ↑ Nicolaus Peters: The new German whaling. Hamburg 1938.

- ↑ WALFANG / ONASSIS: Put on the chain . In: The mirror . No. 18 , 1956 ( online ).

- ↑ Klaus Barthelmess: The opponents of the Olympic Challenger. In: Polar Research. 79 (3), 2009, pp. 155-176. (published 2010), online: Klaus Barthelmess: The opponents of the Olympic Challenger. In: Polar Research. 79 (3), 2009, pp. 155-176. (published 2010), online: epic.awi.de (PDF; 3.3 MB)

- ^ Catches taken: Under Objection. In: iwc.int. Retrieved April 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Japan's whale hunters return - Norway's hunters start. In: proplanta. Retrieved April 3, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Minoru Matsutani: Activists win; whale hunt stops in Antarctic. In: The Japan Times Online. February 16, 2011, accessed February 18, 2011 .

- ^ Norway, Japan prop up whaling industry with taxpayer money. WWF, June 19, 2009, accessed February 19, 2011 .

- ↑ Japan: Whaling in the Name of "Research". In: stern.de . November 19, 2007. Retrieved January 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Humpback whale hunting is temporarily suspended: Japan partially gives in to international pressure. In: nzz.ch. December 21, 2007, accessed January 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Whaling: GOJ noncommital on encouraging Iceland to lower quota (Wikileaks telegram 10TOKYO171). United States Department of State January 27, 2010, archived from the original January 7, 2011 ; Retrieved January 3, 2011 .

- ↑ Christoph Neidhart: Whaling in Japan - What is left of the whale. In: sueddeutsche.de . March 7, 2010, accessed January 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Japan stops whaling. (No longer available online.) In: heute.de. Formerly in the original ; Retrieved February 18, 2011 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ focus.de: Japan stops whaling and calls back whaling fleet. Retrieved February 18, 2011 .

- ^ Judgment in the whaling process: UN court prohibits Japan whale hunting in Antarctica. In: Spiegel Online . March 31, 2014, accessed March 31, 2014 .

- ↑ dw.de

- ↑ Ban remains: Japan fails with whale hunting trick. In: Spiegel Online . April 14, 2015, accessed January 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Research as a fig leaf - Japan kills 333 minke whales - 122 of them were pregnant . srf.ch , May 31, 2018; accessed on May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Japan is killing whales again. In: bernerzeitung.ch . December 26, 2018, accessed December 26, 2018 .

- ↑ Whaling in Japan: Resumption and Responses. September 10, 2019, accessed September 23, 2019 .

- ↑ Hagar & seyðamark. In: heimabeiti.fo. Retrieved January 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Sandra Altherr: Iceland's whaling comeback. (PDF; 611 kB) Pro Wildlife

- ^ Catches taken: Under Objection. In: iwc.int. Retrieved April 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Iceland's Whale Hunting Season Begins Despite Global Moratorium. In: huffingtonpost.com. June 30, 2015, accessed January 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Whaler Loftsson gives on press release from Pro Wildlife from February 25, 2016, German (accessed May 25, 2016)

- ^ Peoples and Cultures of the Circumpolar World I - Module 3: People of the Coast. (PDF; 259 kB) University of the Arctic, p. 7. Retrieved on: July 21, 2015.

- ↑ Greenpeace.org December 5, 2012.

- ^ The Most Senseless Environmental Crime of the 20th Century. In: Pacific Standard , November 12, 2013.

- ↑ Russia releases 100 whales after protests . orf.at, April 9, 2019; Retrieved April 9, 2019. - With contributions from Jean-Michel Cousteau .

- ↑ Felix Schürmann: The gray undercurrent: whalers and coastal societies on the deep beaches of Africa, 1770-1920. Frankfurt a. M. / New York 2017, pp. 485-536.

- ↑ Sperm whale at wale.info. Seen on June 2, 2011.

- ↑ fin whale at acsonline.org (Engl.) ( Memento of 24 April 2013, Internet Archive ), accessed on January 12, 2014.

- ↑ Japanese whaling fleet tracked down . In: Greenpeace . ( greenpeace.de [accessed on July 23, 2018]).

- ↑ in detail the English Wikipedia: en: Yuquot Whalers' Shrine and Alfred Hendricks, ed .: Indians of the Northwest Coast. Change and Tradition. (First Nations of the Pacific Northwest. Change and Tradition.) Westfälisches Museum für Naturkunde , Münster 2005, ISBN 3-924590-85-0 (book accompanying a series of exhibitions, bilingual German-English) Fig. Of the shrine and of ritual dance before the hunt, text on the rites.