Battle of Gettysburg

| date | 1st - 3rd July 1863 |

|---|---|

| place | Adams County , Pennsylvania, USA |

| output | Union victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

|

95,170

|

65,510

|

| losses | |

|

23,049 killed

: 3,155 wounded: 14,529 missing / captured: 5,365 |

20,451 killed

: 2,592 wounded: 12,709 missing / captured: 5,150 |

Brandy Station - Winchester II - Aldie - Middleburg - Upperville - Hanover - Gettysburg - Hunterstown - Fairfield - Williamsport - Boonsboro - Manassas Gap

The Battle of Gettysburg took place from July 1st to 3rd, 1863 near the small town of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania a few miles north of the Maryland border during the War of Civilizations. With more than 43,000 casualties, including over 5,700 dead, it was one of the bloodiest battles on the American continent and is considered one of them together with Vicksburg and Chattanooga and alongside Antietam and Perryville in 1862 and the fall of Atlanta and Philip Sheridan's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864 decisive turning points of the American Civil War. With the defeat of the Northern Virginia Army under General Robert E. Lee , the penultimate offensive of the Confederation on Union territory ended . The initiative then passed essentially to the Union in the eastern theater of war.

The three-day battle began on the first day with a battle of encounters that the Confederates won. The Northern Virginia Army attacked the Potomac Army on both wings the following day , but could not break through the Northerners' positions, so that day ended in a draw. General Lee tried to force the decision on the third day by attacking the center of the Potomac Army, but failed despite a temporary break-in into the positions of the Northerners. The attack force of the Northern Virginia Army was thus exhausted.

prehistory

Goal setting

General Lee proposed to President Jefferson Davis after the victory at Chancellorsville that he should go north and invade Pennsylvania. As a result, the Northern Virginia Army would threaten the capital Washington, DC, as well as the cities of Baltimore and Philadelphia . The Potomac Army would then be forced to follow Lee north. Major General Joseph Hooker , Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army, was due to attack the Northern Virginia Army on a site chosen by Lee. Lee wanted to beat Hooker there again, but this time on Union territory. Other goals were to prevent troops from the eastern theater of war from increasing Ulysses S. Grant's siege of Vicksburg , Mississippi , and to induce the Union to withdraw troops from the coastal areas of the Carolinas and Georgia . A reinforcement of General Joseph E. Johnstons , commander of the Confederate Western theater of war, to the relief of Vicksburg rejected Lee as well as the proposal to reinforce the Confederate Tennessee Army and defeat the Union Cumberland Army in Tennessee . The President and Cabinet, with the exception of the Post Office Secretary, approved Lee's proposal, and even Lieutenant General James Longstreet , Commanding General of the I Corps, accepted the plan.

execution

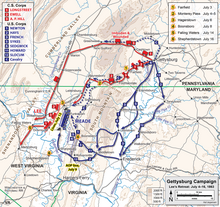

The Northern Virginia Army marched north under cover of the Blue Ridge Mountains . The cavalry under Major General J.EB Stuart was supposed to obscure the movement while at the same time enlightening the movements of the Potomac Army. At Brandy Station on June 9th the biggest equestrian battle on the American continent took place. Further skirmishes of the cavalry at Aldie and Middleburg in Virginia followed. Then Stuart circled the Potomac Army in the east.

After the second battle at Winchester , Lee was able to cross the Potomac unmolested and advance to the Susquehanna . His army of about 75,000 men was spread out in a wide arc on either side of South Mountain . The I. Corps under James Longstreet had the Chambersburg area , the II under Richard S. Ewell the area south of Carlisle and the III. under Ambrose P. Hill reached the Cashtown area . Stuart's cavalry division was east of the Potomac Army, so Lee had no exact information about the movements of the opposing army since June 24. On June 28, when Lee learned from scouts from Longstreets Corps that the Potomac Army had crossed the Potomac north, Lee ordered the Northern Virginia Army to assemble in the Cashtown area.

Eve of battle

US President Abraham Lincoln named Major General George Gordon Meade as Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army on June 28 . Meade intended to provide the Northern Virginia Army before crossing the Susquehanna and convince General Lee to attack the Potomac Army, which had explored defensive positions along Pipe Creek in northern Maryland. However, since Lee had given up his intention to cross the Susquehanna, Meade moved a corps to the Gettysburg area.

J. Johnston Pettigrew's brigade of Maj. General Henry Heth's division had approached Gettysburg on June 30 in search of food and shoes. In the city, however, there was already Union cavalry under the command of Brigadier General John F. Buford . This was able to hold the city because Pettigrew did not accept the battle and dodged west.

Lieutenant General Hill ordered Heth to conduct a violent reconnaissance against Gettysburg for the next day, assuming the forces there were only Pennsylvania militia . In doing so, Hill did not violate Lee's instructions not to engage in major engagements until the Northern Virginia Army rally.

Course of the battle

First day (July 1st)

The brigades of Brigadier Generals James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis - a nephew of the President of the Confederate States - reached the mountain ranges upstream of the city in the northwest at around 7:30 a.m. Expecting little opposition, Heth deployed the two brigades on either side of Chambersburg Pikes and marched toward the city. Brigadier General Buford was not remained inactive in the night and defended dismounted riders - armed with Sharps - carabiners - his two brigades and a Horse Artillery battery along the McPherson Ridge . Buford managed to hold off the superior southerners for more than two hours before he had to evade to Gettysburg.

In these minutes the first two brigades of the 1st Division of the 1st Corps of the Potomac Army appeared and replaced Buford's cavalrymen. Commanding General Major General John F. Reynolds instructed the brigade commanders at McPherson Ridge in the positions on horseback and was fatally wounded. Before that, Reynolds had the commanding generals of the following corps, the XI. and III., instructed to reach the city with their troops more quickly.

The 1st Division of the 1st Corps, whose leadership had meanwhile taken over by Major General Abner Doubleday , managed to hold up the Confederates until about 2:30 p.m. with great losses on both sides. In the meantime, the first brigades of the XI. Reached Gettysburg Corps under Major General Oliver O. Howard and took positions to the north-west and north to the right of I. Corps.

By this time, Heth had brought the division's other two brigades into action. There was also the 26th North Carolina Regiment, with 800 men the strongest in the Northern Virginia Army, which numbered 212 men at the end of the first day and 80 at the end of the battle. Heth himself was shot in the head and was disabled for the remainder of the battle. Brigadier General Pettigrew took over the division.

Lieutenant General Hill had meanwhile introduced Major General William D. Penders Division into the action, so that the 1st Corps of the Union had to evade the city via the Seminary Ridge . Even before this attack began, the divisions of Major General Robert E. Rodes and Jubal Early of the II. Corps under Lieutenant General Ewell had the regiments of the I. and XI. Potomac Army Corps attacked at Barlow Knoll .

When the Union positions finally collapsed to the north and west of the city, Major General Howard ordered them to go to Cemetery Hill south of the city. There, on reaching Gettysburg, he had already ordered Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr's division to maintain this altitude in any case. This made it possible to stop movements, some of which were fleeing, and to reorganize the troops.

Lee had reached the battlefield around 2:30 p.m. and recognized the defensive potential of the heights south of the city for the Union. He therefore called on AP Hill to continue the hitherto successful attack and ordered Ewell to take Cemetery Hill and Culps Hill, if that was feasible - " if practicable ". Hill was unable to continue the attack, however, as his troops had suffered heavy losses and ran out of ammunition. The third division of II Corps would not reach the area west of Gettysburg until evening.

Ewell did nothing to prepare the ground for the attack. But without these preconditions, the storming of the two hills was simply not feasible. Ewell scrutinized the " if practicable " instruction and decided that attack was not possible, thereby forgetting the opportunity to evict the Potomac Army from Culps and Cemetery Hill. Alleged sightings of US troops at York Pike, in Ewell's back and flank, caused confusion in the Confederate management level. These turned out to be irrelevant, but led to the fact that two of Ewell's brigades were temporarily deployed to protect against the alleged threat.

25,000 Confederate and 18,000 Union soldiers faced each other on July 1. Lee had achieved a first great success. In the afternoon he met the commanding general of his 1st Corps, Lieutenant General Longstreet, whose first division would not arrive in the Gettysburg area until the next morning after about 28 km of march. Despite other suggestions from Longstreet, Lee decided to resume the battle on the wings the next day.

Second day (July 2nd)

During the night and morning of July 2, most of the infantry divisions of both armies reached the battlefield, only Longstreet's 3rd Division under Major General George Pickett would not arrive until late afternoon.

Major General Meade defended with the XII. Corps on Culps Hill, to the left with the remains of the I. and XI. Corps on Cemetery Hill , further south with the II. Corps along the Cemetery Ridge and then with the III. Corps under Major General Daniel E. Sickles to the Little Round Top .

Lee's plan of operations for that day was for attacks on both wings of the Potomac Army. Longstreet should have three divisions, including Anderson's division from Hills III. Corps to attack the left wing astride Emmitsburg Road to the northeast. Hill should also threaten the center of the Union lines and ensure that the Potomac Army could not move troops from there to the wings. Ewell's task was to keep the right wing busy with two divisions and to attack if a “ favorable opportunity ” arose. In the absence of precise clarification due to the continued absence of Stuart's cavalry corps, Longstreet's left division under Major General Lafayette McLaws did not attack the left flank of the Union, but headed Sickles' III. Corps.

Sickles had taken positions on his own initiative west of Cemetery Ridge , because the area there was a little higher. He wanted to avoid being exposed to deadly artillery fire again as at Chancellorsville when he had to give up the elevated area, the "high ground" 'Hazel Grove' . By this advance, however, Sickles overstretched the positions of the two divisions of the III. Corps. As Meade Sickles in the afternoon with the words

- "General Sickles, this is in some respects higher ground than that of the rear, but there is still higher in front of you, and if you keep on advancing you will find constantly higher ground all the way to the mountains!"

- (German: "General Sickles, this is in a certain way higher terrain than the one behind you, but there is higher terrain in front of you, and if you go further you will always find higher terrain up to the mountains!")

confronted, it was too late to change positions again. Meade ordered the Potomac Army pioneer leader, Brigadier General Governor Kemble Warren , to scout appropriate positions behind Sickles' corps. Warren saw the possibilities the two Round Tops would offer and recommended that the commanding general of V Corps, Major General George Sykes , immediately send troops there to avert a disaster for the entire Potomac Army. Sykes responded immediately and ordered the 1st Division of the Corps to the Tops.

Attacks on the left wing of the Potomac Army

Longstreet should attack as early as possible; the start of the attack was delayed, however, because Longstreet had to wait for a brigade to arrive and an observation station was recognized on the Little Round Top during the approach . In order to remain undetected, the troops had to go back. When Major General John B. Hood recognized Sickles' positions around 4:00 p.m., Hood wanted to change the plan of operations and attack east of the Round Tops to the north, which Longstreet refused. Hood finally attacked the two Tops and Devils Den at around 4:30 p.m.

After the capture of Devils Den, the Alabama Brigade under the command of Brigadier General Evander McIvor Laws, with the support of two Texan regiments of Jerome Bonaparte Robertson's brigade, attacked in the direction of the Tops. The 15th Alabama Regiment quickly reached the level of the Big Round Top and immediately began approaching the Little Round Top when it came under murderous fire. The 20th Maine Regiment from Colonel Strong Vincent's Brigade had arrived on the hill just ten minutes earlier. The commander of the 15th Alabama Regiment, Col. William C. Oates , recognized the importance of the Little Round Top and tried repeatedly to circumvent the position of the 20th Maine Regiment under Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain on the right, which failed. When the 20th Maine finally ran out of ammunition, Chamberlain ordered a bayonet attack that pushed the 15th Alabama back to its original positions. Little by little, other units of the 1st Division of the V Corps arrived and the situation on the tops was stabilized. Hood's attack on Devils Den was lossy, but successful, but could not be pushed further to the tops.

After Hood's brigades took Devils Den around 5:00 p.m. Law's division attacked the III. Corps, which had meanwhile been reinforced by brigades of the V Corps, at a wheat field and a peach plantation. The Union associations were pushed eastward from the wheat field at around 5:30 p.m., while the Confederates managed to break into the plantation. The troops of III. and V Corps were in disbandment and fled after heavy losses in the direction of the north of the Tops lying Cemetery Ridge , the area given up because of the 'high ground' at the peach plantation by Sickles at noon.

A Meade-ordered reinforcement from II Corps, Brigadier General John C. Caldwell's Division, reached the combat area around 6:00 p.m. and succeeded in stopping the Confederate Corps attack. The Confederates attacked again around 7:30 p.m. through the wheat field and were again repulsed by a counterattack at the northern end of the Little Round Top . The third division of Anderson's AP Hills Corps prepared for the attack began the attack north of the peach plantation against the right flank of Sickles Corps around 6:00 p.m. The two Union brigades deployed there had to evade. This evasive movement was the trigger for the collapse of the entire right wing of the III. Corps.

To allow time to prepare the defense along Cemetery Ridge , the Commanding General of II Corps, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock , ordered the 1st Minnesota Regiment to counterattack the attacking Confederates. Despite the overwhelming superiority of the southerners, the regiment entered and lost 224 of 262 men within a few minutes, thus suffering the highest percentage loss that a regiment of the US Army had ever suffered. Wilcox's Southern Brigade was stopped. However, the other two brigades deployed on the left wing of Anderson's division quickly found the gap left by the collapse and pushed onto Cemetery Ridge . For a short time General Meade and his staff were the Union's only defenders there. Whether the southerners reached the top of Cemetery Ridge is historically controversial - but there is much to be said for it. Brigadier General Ambrose R. Wright was unable to hold the ridge as it received no reinforcements. The brigades deployed to Wright's left moved hesitantly or stopped. One of the brigade commanders even ignored Anderson's express order to proceed. Eventually Wright had to switch back to Emmitsburg Road . The fight came to an end across the board at nightfall. During the attack, Major General Pender was hit in the leg while riding down the front of his division that was forming in support of the attack. Pender died as a result of the amputation. First Brigadier General Lane took over the division, then it was subordinate to Major General Trimble.

Attacks on the right wing of the Potomac Army

One division of the I. and two divisions of the XII. Union corps had begun to fortify Culps Hill that morning. Ewell began the ordered diversion at the same time as Longstreet's attack around 4:00 p.m. initially exclusively with artillery. Major General Meade, however, was not impressed by Ewell's actions. Meade ordered the commanding general of the XII. Corps, Major General Henry W. Slocum , deployed his corps in support of the wavering front on the left wing of the Army. Thereupon Slocum withdrew all forces except the brigade Brigadier General George S. Greenes .

Ewell did not order the attack on both hills until dawn around 7:00 p.m. Three brigades from Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson's division attacked Culps Hill, Early's Cemetery Hill division . The difficulties for the attackers lay in the rapidly falling darkness, the sloping terrain and the developed positions they encountered on Culps Hill.

The attacks of the two brigades attacking in the north from Johnson's division were repelled. The brigade of Brigadier General George Hume Steuart in the south managed to bypass the positions of the Union troops to the south. Here, like the 20th Maine Regiment at the other end of the Potomac Army, the 137th New York Regiment under Colonel David Ireland defended the far right end of the army. The regiment succeeded with great losses in holding the army's right flank with only minor loss of terrain.

Since the troops were not used to fighting in the dark, incidents with high losses occurred: The 1st North Carolina Regiment fired at the 1st Confederate Maryland Regiment. When the remains of the XII. Corps returned to their positions, the soldiers found them occupied by Confederates. To put an end to this mess and to avoid further losses, the division commanders on both sides ended the battle at around 11 p.m. and continued to fight from the positions they had reached at dawn.

Early's brigades managed to advance to the top on Cemetery Hill and capture several artillery pieces. Two newly introduced Union regiments ended the scuffle between the infantry and the gun crews. The Confederate brigade commander, Brigadier General Harry T. Hays , realized that it was no longer possible to distinguish between friend and foe. When he was also attacked by a brigade of the II Corps, he ordered a retreat to the foot of the hill. Rode's division was to take part in the attack on Cemetery Hill . However, this had only reached its starting position after dark. After the fighting ended, Cemetery Hill was again in the hands of the Potomac Army.

The Southerners had missed a great opportunity on Culps Hill - the Potomac Army's main line of communication was on Baltimore Pike , just 600 meters from the positions of the 137th New York Regiment.

Stuart's cavalry had arrived in the Gettysburg area on the afternoon of July 2, but were unable to intervene in the action. As the rest of the Potomac Army's cavalry appeared in the Gettysburg area through this movement, Johnson had to deploy a brigade to counter this new threat.

Major General Meade, after discussing the casualties of the Potomac Army with his staff and the commanding generals, decided to await Lee's attacks the next day. At the end of the meeting, Meade warned Brigadier General John Gibbon , now commanding general of Union II Corps, that if Lee attacked the next day, he would do it in front of Gibbons Corps. Meade said support from the V. and VI. Corps too. The XII. Corps allowed Meade to attack the next morning to recapture the lost positions at the foot of Culps Hills.

Lee, on the other hand, was in a bad mood because he believed that his assignments and plans had been poorly carried out. Longstreet again proposed a strategic bypass of the Potomac Army's left flank, but Lee decided to attack both flanks again the next day, while Stuart was to operate on Ewell's left and behind.

The losses for the 2nd day are difficult to estimate because both armies only determined their respective strengths after the end of the battle. It is estimated that the Northern Virginia Army lost approximately 6,000 men, which meant losses of 30 to 40 percent for the Long Street divisions involved in the attack. The Potomac Army lost around 9,000 men.

Third day (July 3rd)

Lee realized early on the morning of July 3 that his plan was not workable - Longstreet was not yet sufficiently prepared for the attack and Ewell was already embroiled in fierce fighting on Culps Hill. Lee's request to Ewell not to accept the engagement came too late.

The batteries of the XII. Corps had begun bombarding Steuart's positions for 30 minutes at dusk. However, the southerners anticipated the planned attack. In total, Johnson's soldiers attacked three times, but were repulsed each time. The fighting ended around 12:00 p.m. with an attack by two Union regiments, which was carried out head-on due to misinterpretation of the attack orders. The commander of the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment, Colonel Charles R. Mudge, had the order repeated, and then said:

- "Well, it is murder, but it's the order." (German: "Well, it's murder, but an order is an order.")

During the bloody two-day fighting on Culps Hill, the Union lost about 1,000 men and the Confederates 2,800 men - a fifth and a third of the respective team strength.

Encouraged by the fact that the day before the Confederate troops had almost succeeded in breaking through to the right of the center of the Potomac Army, Lee decided, by modifying the plan from the previous day, to attack the center of the enemy.

Pickett's batch

170 Confederate cannons began at 13:00 a two-hour bombardment of artillery positions between Cemetery Hill and the Round Tops along Cemetery Ridge . Initially, 80 Potomac Army guns returned fire, but soon the artillery commander, Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt , ordered the fire to cease in order to have enough ammunition for the anticipated infantry attack. Although the Confederate fire was mostly too high due to poor visibility, the losses on both sides were considerable.

The artillery had almost fired at around 3:00 p.m. and the infantry attack began. Pickett's division from I. Corps and Isaac R. Trimbles (formerly Penders) and Pettigrews (formerly Heths) divisions from III. Corps AP Hills. The total strength of the troops deployed was approximately 12,000 men. The attack began at Seminary Ridge, more than a mile wide. The brigades advanced slowly eastward over a kilometer of open ground toward the Union positions at Cemetery Ridge . Immediately after crossing Seminary Ridge , the Union batteries opened fire on the Confederate soldiers along Cemetery Ridge . Especially the flanking fire from Cemetery Hill and north of Little Round Top tore large gaps in the attacking lines. When the attackers were only 360 m away, the artillery fired with grapefruit , and the Union infantry took part with musket fire . The Confederates cut the line to half a mile and kept attacking. Pickett's division turned northeast. This gave the division the flank of the Union batteries, which could now fire parallel to the attacking lines. Pettigrew's left flank was suddenly exposed to a flank attack by the 8th Ohio Regiment, which resulted in the brigade deployed on the left escaping to the starting positions on Seminary Ridge .

The attacking Confederates huddled more and more in the center and formed a formation 15 to 30 men deep. At a low stone wall, which was at a right angle here, around 200 men under the leadership of Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead broke into the positions of the Union infantry and reached the first artillery positions. In a counterattack, the Confederates were thrown from their positions again. This part of the stone wall - called " The Angle " because of the angle - later became known as the " High Water Mark of the Confederacy " . The rest of the Confederate units and units slowly retreated to Seminary Ridge when it became clear that no reinforcements were being followed. The entire attack, later called Pickett's Charge , lasted a little over an hour.

When Major General Pickett reported back to Lee, the latter ordered his division to prepare for a counterattack by the Potomac Army. Pickett replied:

- "General Lee, I have no division now." (German: "General Lee, I have no more division.")

The Confederate losses were enormous - nearly 5,600 men, including all three brigade commanders and all 13 regimental commanders from Pickett's division. However, the Union counterattack did not take place. Although the northern states' casualties were much lower, at around 1,500 men, the Potomac Army's fighting strength was also exhausted and Meade was content to have held the positions.

Battles of the cavalry

Major General Stuart and the Confederate Cavalry were to oversee the left flank of the Northern Virginia Army and cut the main line of communication behind the Potomac Army. Three miles east of Gettysburg, Stuart with four brigades, approximately 3,430 horsemen with 13 guns, encountered Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg's division at around 1:00 p.m. , reinforced by Brigadier General George A. Custers Brigade, around 3,250 horsemen. Stuart attacked immediately with the 1st Virginia Regiment, but was counterattacked by the 7th Michigan Regiment under Custer's personal leadership - “ Come on, you Wolverines! ”- thrown back in combat with pistol and saber. With reinforcements, Stuart managed to put Custer's riders to flight. Stuart ordered another attack with the bulk of Brigadier General Wade Hampton's brigade . With sabers drawn, the Hamptons riders attacked the 7th Michigan Regiment. Gregg then attacked the flanks of Hamptons. Pressed from three sides, the Confederate horsemen evaded the starting positions. The entire battle lasted about 40 minutes. Though a tactical tie, the battle spelled a strategic defeat for Lee because Stuart failed to get into the rear of the Potomac Army.

The Union cavalry division under Brigadier General Hugh J. Kilpatrick attacked Hood's division positions from the south on both sides of Emmitsburg Road at around 3:00 p.m. In several waves Kilpatrick let the cavalry regiments attack infantry in positions first mounted, later dismounted. The Confederates repulsed all attacks, and a lieutenant from an Alabama regiment fired his soldiers with the words, "Cavalry, boys, cavalry! This is not a fight, this is a joke, tell them! ”.

These poorly thought out and executed cavalry attacks marked the lowest point in the history of Union cavalry and the last major hostilities of the Battle of Gettysburg.

After the battle

The Northern Virginia Army had set up defense on July 4th in anticipation of Meade's attack. However, the latter decided against the risk of an attack, which later earned him severe criticism.

The Northern Virginia Army left the positions in the pouring rain that evening and marched on Fairfield Road to South Mountain and from there via the towns of Hagerstown and Williamsport , both in Maryland, to Virginia. During the retreat, Lee paid special attention to the wounded and the supply columns, the former out of responsibility as leaders, the latter because they were the only way to enable the army to continue fighting. Lee managed to bring the wounded, some 5,000 prisoners, the captured weapons and ammunition and the supply vehicles to Virginia with only minor losses, some of them being transported under horrific conditions - not even straw on the wagon and too few paramedics to look after them.

Meade followed Lee only half-heartedly. Even when the flooding Potomac forced Lee to remain on the north bank, it was too long before the Potomac Army got there. The battle with the rearguard on July 14 at Falling Waters in what is now West Virginia ended the Gettysburg campaign.

Reasons for defeat and consequences

Lee hadn't wanted the Battle of Gettysburg. This was clearly expressed in his July 1st order, in which Lee always pointed out that Longstreet's corps was not yet available. The battle began, to use a modern term, as an encounter. Both AP Hill and Lee, who later arrived on site, realized that the Northern Virginia Army was sufficiently superior at that moment to turn the battle in their favor. Even if the first opportunity to beat the opponent was missed, Lee believed that he could only keep the initiative by attacking.

- "No, the enemy is there, and I am going to attack him there." (German: "No, the enemy is there and I will attack him there too.")

Confederate mistakes and problems

Northern Virginia Army reclassification

Lee had long thought of regrouping the Northern Virginia Army because the corps were too large for him and therefore difficult to manage. A candidate for the post of Commanding General was AP Hill after the Battle of Antietam . After Stonewall Jackson's death , the personnel situation became scarce. Only Hill and the recently recovered Ewell remained as suitable candidates. Hill had already led a division under Lee's direct command; Ewell had been division commander under Jackson. Neither of them had ever led a corps in battle. President Davis approved the reorganization, and on May 30th, Lee, Special Order No. 146, commanded the new organization. Hills III. Corps consisted of two newly formed divisions with new division commanders and Anderson's division consisted of Longstreets Corps. Ewell's II Corps consisted of the divisions from Jackson's former corps with the experienced division commanders. Because of this far-reaching reorganization, cooperation within the command levels of the Northern Virginia Army was no longer as tried and tested as before. Ewell, for example, had previously served under Lieutenant General Jackson, who was wounded in the Battle of Chancellorsville and died shortly after of pneumonia, and was unfamiliar with Lee's orders. Lee granted the commanders directly reporting to him a great deal of discretion. Ewell couldn't do anything with that discretion. There had been no such thing under Jackson; the latter had given detailed orders and left nothing at the discretion of his troop leaders. Therefore, on July 1, Ewell did nothing to create the possibility of a promising attack. However, false reconnaissance sightings also played a role, according to which troops from the Northern States were in Ewell's back at York Road.

Lack of education

JEB Stuart's cavalry was Lee's primary reconnaissance vehicle. On June 23, Lee had ordered Stuart to proceed, leaving the implementation to Stuart, as he could better assess the situation. Lee had directed Stuart to make sure to connect to the right wing of II Corps as soon as the Potomac Army began to move. Lee could not foresee that Stuart would take this opportunity to ride again for the Potomac Army and disregard a clear assignment. Since Stuart was east of the Potomac Army on June 30th, Lee had no knowledge of the enemy's behavior. The violent reconnaissance on July 1 would certainly not have taken place if Lee had suspected that the supposed Pennsylvania militia was a cavalry division, closely followed by two corps of the Potomac Army.

Lack of concentration

Since the fall of 1862, the Northern Virginia Army had had to surrender several brigades to other military areas. In planning his offensive to Pennsylvania, Lee tried to return these formations to the army. Here, however, problems arose with President Davis and General Daniel H. Hill , who commanded the North Carolina Defense Division. Hill suggested swapping out weakened Northern Virginia Army brigades for fresh military brigades. Lee refused this, except in one case, and reclaimed the Ransom, Cooke, Corse and Jenkins brigades, which he saw only as a kind of loan. Theoretically, Hills' defense area was under Lee, so this could have simply ordered the deployment of the brigades mentioned. Instead, he gave Hill a discretionary order. However, Hill saw himself threatened by the troops facing him from the northern states and did not move the desired troops. As a result, Lee complained to Davis on May 30, asking to be relieved of command of Hill's military area. Ultimately, Lee received two brigades, but not the one he wanted: he was assigned the relatively inexperienced Pettigrew and Davis brigades. In the meantime it also looked as if two more brigades would be subordinate to him, but this was thwarted by a local advance of the northern states in the area of Richmond. On June 7th Lee tried again to get at least the Cooke and Jenkins Brigades subordinate. On the same day he pointed out that according to northern newspaper articles the Union troops in South Carolina were weakened and therefore suggested that General Beauregard, who was in command there, be sent to the west to support General Johnston or to the north to support him. However, this proposal had no consequences either. Lee received neither the brigades he had requested for his advance into Pennsylvania, nor support from South Carolina. The effects of this can only be guessed at. The strength of the four Brigades, Cooke, Ransom, Jenkins and Corse, which Lee asked so often, was estimated to be more than 9,000 men.

Coordination problems

Lee was with II Corps on the evening of July 1 and, in the presence of the Division II Corps commanders, asked Ewell if he could attack Cemetery Hill or if he would prefer an attack on the Army's right flank. Significantly, it was not Ewell who answered, but Jubal Early and Ewell nodded speechless at the answers. No decision was made. That night, Ewell rode up to Lee and reported that he saw the possibility of attacking Culps Hill. On July 2, Ewell was unable to coordinate his corps' attacks on Culps Hill and Cemetery Hill . Lee failed to intervene here and again let Ewell conduct the attacks at his discretion. Ewell didn't use the third division at all.

Longstreet had deeply internalized Lee's original intention to attack the enemy on a site chosen by the Confederates. During the first two days of the battle, he suggested to Lee that the Northern Virginia Army be pushed between Washington and the Potomac Army and attacked there. Longstreet delayed the start of the attack on July 2 and changed the plan of operations independently, so that Lee had to agree to introduce the three divisions intended for the attack into the battle at different times and locations. Lee, who was at Longstreet in the early afternoon, did nothing about Longstreet's flirting and rode back to his headquarters without vigorously putting Longstreet in its place.

Even after the attack began on July 2, the Confederates continued to experience coordination problems. The attack on the left flank of the Union Army began promising, but the gradual intervention of the brigades (the "attack en échelon") broke off when two brigades of the Anderson division did not start the attack as planned. This resulted in Wright's brigade receiving no support at Cemetery Ridge. Similar coordination problems were encountered in the attack by Early's Division on Cemetery Hill on the evening of July 2, when the movements of the Confederate Divisions Rodes, Early and Pender (after being fatally wounded under General Lane) were not well coordinated, making Early's two brigades not were supported.

Pickett's attack

On July 3, Meade Lee initially thwarted the plans when the Potomac Army attacked Ewell and prevented joint action by the Northern Virginia Army on the wings. Longstreet had, contrary to Lee's orders, prepared an attack against the left flank of the Potomac Army. Since a coordinated attack had become impossible, Lee decided to attack the center of the Potomac Army. Lee hired Longstreet to carry out the project. This did not want to lead the attack because he thought it was wrong.

Pickett's attack was an absurd possibility from today's perspective. At the time of the Napoleonic warfare, such an attack was quite normal. Especially at Chancellorsville , Lee's troops had repeatedly attacked the positions of the Potomac Army head-on and had success. Lee had unlimited faith in the superior ability of the Northern Virginia Army, especially the great victory at Chancellorsville and the July 1st defeat of the Potomac Army made him believe it. But the enemy was not the poorly run Potomac Army of May, but a well-run and valiant army.

Pickett had recognized early on that once the target was taken, reinforcements would be needed to expand success. Even as they approached, he sent an officer to Longstreet to send reinforcements on the march. Longstreet was otherwise busy - throughout the attack he was more concerned with the little things than the attack. Indeed, Anderson's division was ready. He wrote in his report on August 7, 1863:

- "... I was about to move forward Wright's and Posey's brigades, when Lieutenant-General Longstreet directed me to stop the movement, adding that it was useless, ..." (German: "... I was just about to march to Wright's and Posey's brigades when Lieutenant General Longstreet ordered me to stop the movements and added that it was useless ... ").

Lee, as always after the assignment to attack, had left the entire process at Longstreet's discretion. Here Lee could have seen that Longstreet was not convinced of the success of the attack and therefore had to entrust another officer to carry out the attack.

Consequences of the battle

Grant captured Vicksburg the day after Pickett's charge . Lee had managed to prevent Grant reinforcements, but the Confederation had defeated itself. The undeniable differences of opinion between Johnston and Jefferson Davis led to the fall of Vicksburg.

The Battle of Gettysburg was one of the seven crucial turning points in the course of the Civil War. The strategic offensive power of the Northern Virginia Army was lost, and the Confederation was now on the strategic defensive in all other theaters of war.

The devastating effects of the battle were still visible four months later when the National War Cemetery was inaugurated on Cemetery Hill on November 19 . There President Lincoln held the famous Gettysburg Address , in which he called on the nation to believe in a common future for the warring factions so that no soldier would die in vain.

The Northern Virginia Army arrived in Virginia in good order. The Confederates had been defeated but not defeated. The material losses were limited. The personnel losses weighed heavily. Lee managed to restore the army's human and material combat strength after returning it to Virginia. The Northern Virginia Army fought for nearly two years, remaining a dangerous enemy on the battlefield at all times.

Gettysburg and 'The Lost Cause'

General Lee found words of encouragement for the returning soldiers. Many tore their hats off their heads at the sight of him and cheered Lee. To Pickett, Lee said:

- "... this has been my fight and upon my shoulders rests the blame." (German: "This was my fight and only I am responsible".)

In his report on the campaign, Lee consistently did not blame any of his subordinates for the defeat. Lee was dejected after the battle. He did not neglect his duties as Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Virginia Army and led the defeated army back to Virginia vigorously. Once there, Lee asked the President to relieve him on August 8, 1863.

The discussion about the ' Lost Cause ' began with the end of the civil war. The aim was to keep the soldiers of the south high in self-esteem. They just had to give way to the superior armies of the north. Soon was ' Confederate Memorial Day ' introduced, where the victims of the South was thought. In the early 1870s founded early and a few other former leaders, the ' Southern Historical Society (SHS)' . They posited some truths of Confederate intentions during the war. At the same time the heroization of Generals Lee and Jackson began.

The New York Times wrote an article on the Potomac Army in 1872. James Longstreet briefed the editor in charge of decisions made during the Battle of Gettysburg, as he saw them as should have been made. Longstreet accused General Lee of making decisive mistakes.

General Early attacked Longstreet therefore in a speech on the second anniversary of General Lee's death at Washington and Lee Universities. Early branded Longstreet as a renegade marked with the Mark of Cains. In his response, Longstreet accused Ewell and Stuart of complicity in the defeat. Answers and replies went back and forth, and other personalities from the South also spoke up. The 'lost cause ' was given new nourishment.

General Longstreet was particularly suited to be the main culprit in the defeat. Longstreet had not been squeamish about his ex-wartime comrades in his memoirs in which he tried to justify his actions. He was friends with Ulysses S. Grant before the war and revived that friendship. And - Longstreet joined the Republican Party .

Longstreet was practically ostracized and withdrew entirely. His reputation as a leader was still preserved with the soldiers. Years later, when Longstreet traveled to a memorial service, the veterans recognized him and greeted him with applause.

The discussion about the ' Lost Cause ' drew more and more circles over the years and, besides the people involved in Gettysburg, also included other leaders of the Confederation. It only decreased in intensity towards the end of the 20th century. Those responsible for these discussions succeeded in giving Lee and Jackson the status of heroes in both warring factions and maintaining them to this day.

Cultural impact

The Battle of Gettysburg had repercussions on a cultural level as well. Numerous participants, especially on the side of the Union, became "heroes" of the nation through their role in the battle, such as Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain , John Buford or Winfield Scott Hancock. On the part of the Confederation, George Pickett was best known. This was supported by the implementation of the battle in film and literature. Gettysburg is considered the most widely written battle of the Civil War. The novel The Killer Angels , published in 1973 by Michael Shaara , is particularly well-known . The author describes the battle and pays special attention to the role of the 20th Maine Regiment and its commander, Colonel Chamberlain. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a film in 1993 under the title Gettysburg . Gettysburg is also the subject of numerous computer games, and the power metal band Iced Earth processed the battle musically in a half-hour suite called Gettysburg 1863 (on the album The Glorious Burden ).

The Gettysburg National Military Park was created around the battlefield and military cemetery, which Abraham Lincoln made his famous speech, the Gettysbury Address , at the opening .

USS Gettysburg was and is also the name of three US Navy warships.

See also

- List of brigades of the Confederation Army at the Battle of Gettysburg

- List of the Brigades of the Union Army at the Battle of Gettysburg

- List of wars and battles in the 19th century

- Detailed sketches of the places and times of the battle

literature

- United States War Department: The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Govt. Print. Off., Washington 1880-1901

- Mark Adkin: The Gettysburg Companion. The complete guide to America's most famous battle. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg 2008, ISBN 978-0-8117-0439-7 .

- Scott Bowden & Bill Ward: Last Chance For Victory: Robert E. Lee And The Gettysburg Campaign. Da Capo Press, 2003, ISBN 0-306-81261-4 .

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command . New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5 .

- William C. Davis : The American Civil War - Soldiers, Generals, Battles. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0384-3 .

- Shelby Foote : The Civil War: A Narrative. Volume 2 ( Fredericksburg to Meridian ), New York 1986, ISBN 0-394-74621-X .

- Gottfried M. Bradley: Brigades of Gettysburg - The Union and Confederate Brigades at the Battle of Gettysburg . Skyhorse Publishing, New York 2002, ISBN 978-1-61608-401-1 .

- James M. McPherson: Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg. Crown Journeys, New York NY 2003, ISBN 0-609-61023-6 .

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg - The First Day . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8078-2624-3 .

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg - The Second Day . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8078-1749-X .

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8078-2118-7 .

- Stephen W. Sears: Gettysburg. Mariner Books, New York 2004, ISBN 0-618-48538-4 .

- Steven E. Woodworth: Beneath a Northern Sky: A Short History of the Gettysburg Campaign . Wilmington, DE: SR Books (scholarly Resources, Inc.), 2003. ISBN 0-8420-2933-8 .

Web links

- Detailed description of the battle including animations by the National Park Service (English)

- The Battle of Gettysburg - Documents, Biographies and Essays

- Billy Arthur, Ted Ballard, Staff Ride Briefing Book, Gettysburg, engl.

- Animated map of the course of the battle

- Gettysburg in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Billy Arthur / Ted Ballard: Gettysburg Staff Ride. (pdf) US Army Center of Military History, p. 29 , accessed March 29, 2020 (English, troop strength and losses).

- ↑ John Busey and David Martin, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, state the troop strengths: Potomac Army: 93693; Northern Virginia Army: 70136

- ↑ The figures on losses by the Confederation vary between 20,000 and 28,000 men. See also: losses. Statista GmbH, 2020, accessed on March 30, 2020 (Battle of Gettysburg: Troop strength and losses).

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom , p. 858

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom , pp. 646 ff

- ^ Withdrawal of troops. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 24, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXV, Part II, p. 791).

- ^ No weakening of the Northern Virginia Army. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 24, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXV, Part II, p. 790).

- ^ Longstreets proposal. Perseus Digital Library, accessed August 24, 2015 (English, General James Longstreet: From Manassas to Appomattox, p. 331).

- ^ Davis' consent. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 24, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXV, Part II, pp. 842f).

- ↑ Lee's account of the battle. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 25, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXVII, Part II, p. 316).

- ↑ James McPherson, Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg , pp. 34f - McPherson refutes this myth

- ^ Losses of the 26th North Carolina Infantry Regiment. www.civilwarhome.com, April 4, 2009, accessed August 25, 2015 (Fox's Regimental Losses, Chapter XV).

- ↑ Attack if possible. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 25, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXVII, Part II, p. 318).

- ↑ James McPherson, Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg , p. 62

- ^ Harry W. Pfanz: Gettysburg- Culp's Hill & Cemetery Hill , 1993, pp. 67f., 77f.

- ^ Warren W. Hassler: George G. Meade and His Role in the Gettysburg Campaign. (pdf) In: Pennsylvania History vol. 32, no.4 . PennState University Libraries, October 1965, p. 398 , accessed March 27, 2020 (Sickle Advances).

- ↑ Fox's Regimental Losses , Chapter III: Losses 1st Minnesota Regiment

- ^ Robert Underwood Johnson / Clarence Clough Buel: Battles & Leaders of the Civil War , Volume 3, p. 314: Attack in the center

- ↑ An order is an order. National Park Service, April 17, 2016, accessed December 17, 2017 (Gettysburg Seminar Papers: Unsung Heroes of Gettysburg).

- ↑ Pickett's answer. IMDb, accessed on December 17, 2017 (English, IMDb Gettysburg Quotes).

- ↑ ' Wolverines ' (wolverines) is the nickname of the people of Michigan

- ^ Making Sense of Robert E. Lee. Smithsonian.com, accessed April 25, 2019 .

- ^ Douglas S. Freeman, Robert E. Lee , Volume III, Chapter 2 Detailed description of the staff discussion

- ^ The War of the Rebellion , Series I, Volume XXV, Part II, p. 840: Special Orders No. 146

- ^ The War of the Rebellion , Series I, Volume XXVII, Part III, p. 923: I leave the implementation to your judgment

- ↑ This army has been diminished since last fall. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 25, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXV, Part II, p. 833).

- ↑ a b Stephen W. Sears: Gettysburg. P. 49.

- ↑ You will see that I am unable to cooperate under these circumstances. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 25, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXV, Part II, p. 832).

- ↑ Stephen W. Sears: Gettysburg. P. 50.

- ^ Cooke and Jenkins should be directed to follow me. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 25, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXVII, Part II, p. 293).

- ↑ Send Beauregard to the west or to reinforce my army. Cornell University Library, 2018, accessed April 25, 2019 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXVII, Part II, pp. 293f).

- ^ Scott Bowden & Bill Ward: Last Chance for Victory. P. 38.

- ^ Pfanz, Gettysburg-Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill , pp. 280f. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign , p. 429.

- ^ Douglas S. Freeman , Volume III, chap. VIII p. 110: Trust in the Army

- ^ Southern Historical Papers , Volume 31, pp. 228-236: Request for reinforcement

- ^ The War of the Rebellion , Series I, Volume XXVII, Part II, p. 615: No Support

- ^ Douglas S. Freeman , Volume III, chap. VIII p. 114: Without trust in victory

- ^ Douglas S. Freeman , Volume III, chap. VIII p. 129: I am responsible

- ^ The War of the Rebellion , Series I, Volume LI, Part II, pp. 752f: Replacement as Commander-in-Chief

- ^ MacMillan Information Now Encyclopedia: The Confederacy (excerpt) The Lost Cause

- ↑ All documents related to the dispute are listed in the Southern Historical Society Papers . Excerpts from it at: The Longstreet-Gettysburg Controversy

- ↑ James Longstreet: From Manassas to Appomatox : Longstreet's Memoirs

Coordinates: 39 ° 48 ′ 15 ″ N , 77 ° 14 ′ 12 ″ W.