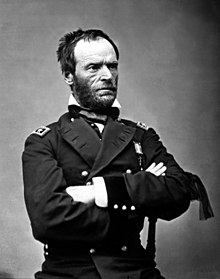

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (* 3. February 1807 at the family seat Cherry Grove in Farmville , Prince Edward County , Virginia , † 21st March 1891 in Washington, DC ) was until 1861 brigadier general in the US Army and one of the highest-ranking generals of the confederate army in American Civil War .

Johnston is considered one of the most capable, but also one of the most controversial generals in the Confederation because of the defensive strategy he prefers. He was the only general of the southern states (at different times) commander in chief of both main combat units of the south: first he commanded the Northern Virginia Army , later the Tennessee Army .

Life

Until the outbreak of civil war

Joseph Johnston was the son of Peter and Mary Johnston (nee Wood). Peter Johnston had fought as an officer in the Revolutionary War and was then a delegate in the Virginia Parliament, where he also acted as Speaker of the House. Mary Johnston, in turn, was a niece of Patrick Henry .

Joseph Johnston attended the Military Academy at West Point , New York and graduated in 1829 as the thirteenth of his class. The future General Robert E. Lee , who succeeded him as Commander in Chief after the Battle of Seven Pines , was his classmate. Johnston was promoted to lieutenant upon graduation and assigned to the artillery . He fought in the Black Hawk War , the Second Seminole War, and the Mexican-American War . In the latter he served on the staff of General Winfield Scott , was wounded five times and twice with a brevet excellent. In 1845 he married Lydia McLane († 1887), who was 15 years his junior. The marriage was very happy, according to all reports, but remained childless.

After his wedding, Johnston served in Texas and Kansas, among others . In 1855 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, after he had already been awarded the relevant brevet rank in Mexico, and appointed regimental commander of the 1st US Cavalry Regiment in Fort Belknap, Texas. Johnston was named Quartermaster General of the US Army in 1860 and promoted to Brigadier General. He was the first West Point graduate to achieve this rank.

When the Civil War began, it was not initially clear whether Johnston would join the South. He was not a supporter of slavery and considered secession itself to be rather unconstitutional, even though he believed in the "right to revolution". The Commander in Chief of the US Army, Major General Scott , like Johnston and Lee from Virginia, tried to convince Johnston to stay in the Union Army . Scott had spoken to Johnston's wife, Lydia, about it. This made it clear to Scott, however, that her husband would by no means remain in an army that might attack his home state. It was clear to Johnston that if Virginia left the Union, he would fight for Virginia too; as in Lee's case, Johnston's loyalty was more to his home state than to the Union.

Johnston quit his service in the US Army after the secession of Virginia on April 22, 1861 and joined the Virginia Army; he was one of the most senior Union officers who joined the southern states. Major General Lee, who ruled the Virginia Land Forces and who appreciated Johnston from their time at the Military Academy, proposed that Governor Johnston be promoted to Major General of the Volunteers. At the same time he was to be given command of the troops around the capital Richmond . The governor appointed Johnston. The Virginia government assembly approved only one major general post and that was occupied by Lee. Johnston was eventually promoted to Brigadier General of the Confederate Army after Virginia joined the Confederation.

Manassas and the Peninsula Campaign

Johnston took over command of the Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia , with whom he reinforced General Beauregard in the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, and thus had a not inconsiderable part in the Confederate victory. Though senior, he left Beauregard in charge. At the end of August he was promoted to general in the Confederate Army with four other officers . Always honored, Johnston complained to President Jefferson Davis that he was only fourth on the nomination list - even though he should have been promoted ahead of the rest in seniority and a higher rank than the rest in the US Army had dressed. This was only the beginning of a long series of arguments between Johnston and the President.

Johnston raised the Northern Virginia Army in the winter of 1861/62 and led them in the first phase of the Peninsula Campaign . He acted defensive , similar to what happened later in Georgia . Johnston succeeded several times in preventing the Potomac army , which was more than twice as strong, from advancing rapidly on Richmond. In order to achieve this, however, he always had to give up terrain. Seriously wounded in the poorly coordinated Battle of Seven Pines , in which Johnston attacked his pre-war friend, Major General McClellan , not least at the urging of the President , he was succeeded on June 1, 1862 by General Robert E. Lee as Commander in Chief. When Johnston later learned of the outcome of the Battle of Fredericksburg (there, the Commander-in-Chief of the Potomac Army, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside , division after division had been attacked against the southerners defending from a ravine and suffered heavy losses), he said:

What luck some people have. Nobody will ever come to attack me in such a place.

“ How lucky some people are. Nobody will ever attack me in such a place. "

The fall of Vicksburg

After his recovery, Johnston was named Commander of the Western Theater by President Davis in late 1862. Under him were the Tennessee Army General Braxton Braggs and the Mississippi Army Lieutenant General John C. Pembertons . Johnston himself was not directly subordinate to any troops. The army commanders in chief were instructed to report not only to him but also to the president. As a result, the armies received orders directly from the president. With the invasion of Mississippi by Major General Ulysses S. Grant , Johnston came to the conclusion in his assessment of the situation that Mississippi and Tennessee could not be held against the overwhelming power of the Union at the same time. He asked the President which state should be abandoned - this was a political decision, not a military decision. Falling into the Confederacy's old mistake of defending everything, President Davis ordered Vicksburg , Mississippi, to detach with Johnston's available forces, initially 5,000 and later more than 20,000 men.

Johnston ordered Pemberton on May 2, 1863, when Grant had just landed in Mississippi, to attack this immediately with all available forces, since an army was most vulnerable after landing. Pemberton was reluctant to carry out this order. Johnston himself believed that reinforcing the Tennessee Army was of more importance to the Confederation than Vicksburg's claim. When the Union attacked Tennessee, the Confederate heartland threatened to be divided as far as Atlanta , Georgia. The loss of Vicksburg, painful as it would be, only cut off a peripheral area. Johnston had to give up his headquarters in Jackson, Mississippi in May when Maj. General Grant overran defensive positions on his march to Vicksburg, ultimately capturing and pillaging Jackson. Before dodging, Johnston ordered Pemberton to unite with his weak forces northwest of Jackson and then jointly attack Grant. Pemberton was also reluctant to carry out this order.

After the containment of Vicksburg, Pemberton did not break out as suggested by Johnston. Considerations in Richmond to send further reinforcements to the west (Generals Bragg and Taylor had already inevitably deployed some major formations) were blocked by General Lee, who believed he needed every man for his planned campaign to the north - Lee's campaign was supposed to be end in the battle of Gettysburg . Pemberton had to surrender on July 4, 1863. With the fall of Vicksburg, the Confederation lost its last land connection to the area west of the Mississippi. Johnston had evaded the Union troops and secured with about 20,000 men the area around Jackson to the west in order to prevent Grant from breaking through to the east. Johnston hoped to lure Union forces into attacking the city's fortifications. Major General William T. Sherman , who commanded the troops outside Jackson, did not fall into this trap and instead began to encircle the city. Johnston then gave up on Jackson a second time on July 16, thereby saving his army. The fall of Vicksburg had a marked shock effect on the Confederation. Responsibility for the defeat was put on Johnston. At the same time, this strengthened the conviction of many in the capital, Richmond, that Johnston was acting too defensively and shying away from open combat. The cause of the defeat, however, was the president's wish to defend everything and the unreasonable leadership conditions, through which the army commanders received instructions directly from the president and which were diametrically opposed to the intentions of their immediate superior.

Commander in Chief of the Tennessee Army

Johnston took command of the Tennessee Army from Braxton Bragg on December 27, 1863. The army was in a demoralized state after the previous fighting. Johnston was able to restore morale quickly and with his troops in 1864 during the Atlanta campaign with great skill, the advance of Major General Sherman and his troops, which were more than twice as strong, slowed down extremely. Johnston wanted to face the enemy at Cassville , Georgia in May 1864, but the plan was dashed by a panic reaction by John Bell Hood , a commanding general of Johnston. Johnston had the Tennessee Army dig field fortifications at Kennesaw Mountain in June and awaited the enemy from them. It was the most one-sided fight in the entire Atlanta campaign and a definite Confederation victory. Sherman had lost about 3,000 dead and wounded, while Johnston had lost barely 600 men; low casualties compared to frontline operations in Virginia, but highest in operations in Georgia. Sherman's campaign was hardly stopped by this, mainly due to the numerical superiority of the Union troops. Sherman succeeded again and again in the further course of the campaign to outflank Johnston, who was still trying to find the right place and time for a decisive battle.

Despite its success, Johnston's defensive strategy met with little approval in Richmond. When Johnston declared that he wanted to leave the defense of Atlanta largely to the militia in order to have the army available for operations in the open, the politicians feared that the strategically important city would be abandoned without a fight. President Davis wasn't particularly fond of Johnston anyway - especially since one of Johnston's friends was Senator Louis Wigfall, an opponent of Davis - so in July 1864 Johnston was replaced by the more aggressive Hood. The replacement was also the result of efforts by Bragg, who wanted Johnston to be replaced and who thought Hood was the right man. Although Johnston did appreciate the Texan Hood, the latter had intrigued repeatedly against Johnston and had written quite straightforward letters to Richmond in which he had criticized his superior's command style. The replacement of Johnston was not without controversy; General Lee, for example, was not convinced that Hood was the right choice. So he characterized him as:

All lion, none of the fox

“Leo through and through, not a bit fox. "

Johnston's troops, who adored and respected him, took the replacement extremely negatively. When Johnston's departure, the Tennessee Army provided a form of honor for "Old Joe", as Johnston was called by his men; some even cried and are said to have publicly threatened mutiny. Many of the officers and men remembered the state of the army under Bragg. The fact that the army was now a vigorous association again, whose soldiers had self-confidence, was without exception attributed to Johnston. Rather reserved in private, he was friendly in the field and exuded a natural authority that rubbed off on the soldiers. Johnston himself announced his attachment to the Tennessee Army soldiers. After Richmond he wrote that the enemy had penetrated less deeply into Georgia (where Johnston had organized the defense) than into Virginia; in addition, his army is in relation to significantly stronger forces than is the case with Lee's army in Virginia.

Hood suddenly seemed concerned that he was up to the task. He later blamed Johnston for simply leaving when he had promised to stay. Johnston, however, insisted that he had made no such promise and that Hood had even discussed his intention to attack Sherman at Peachtree Creek . In fact, it is unlikely that Johnston Hood made any promises, especially since several contemporary witnesses tended to confirm Johnston’s statements. Sherman was delighted with the replacement of Johnston - years later he wrote that the Confederation had done him the greatest favor by replacing the thoughtful defensive strategist Johnston with Hood. Union troops had only waited for the open battle that Hood was expected to take place. In fact, Sherman was right in his assessment, because the Hood-led offensive in Tennessee ended in fiasco when the Tennessee Confederate Army in Nashville , Tennessee was virtually destroyed. Hood had also been unable to prevent the fall of Atlanta.

Campaign in the Carolinas and surrender

Johnston was to take command of all forces east of the Mississippi except for the Northern Virginia Army in February 1865. Johnston almost didn't take the offer. He was bitter when he remarked that he had only been chosen to surrender. It was only when his friend Wigfall informed him that it was not Davis but his old friend from the Lee Military Academy who was behind his installation that Johnston drew courage. His feelings for Lee were split, he admired and envied him. When Sherman set out on his march through the Carolinas , at the urging of Robert E. Lee, Johnston was again given command of the Tennessee Army. Lee was Commander in Chief of the Confederation Land Forces at the time. Johnston, however, could not stop the advance of the outnumbered Sherman; the Tennessee Army's losses had been too high in the past few months.

Despite these extremely unfavorable conditions, Johnston Sherman opposed himself again in March 1865 near Bentonville , North Carolina . Johnston could only muster 20,000 men, while Sherman had 60,000 men. The battle ended in favor of the Union. The Tennessee Army had nearly three times the Union's casualties, but Johnston was still able to dodge vigorously. However, Lee's attempts to unite with Johnston's army failed.

Johnston surrendered, with the complete annihilation of his troops in mind and unwilling to lead them into guerrilla warfare, on April 26, 1865 - 17 days after Lee's surrender, which left Johnston little choice but to negotiate. The Tennessee Army's surrender took place at Bennett Place , near Durham , North Carolina to Major General Sherman. Originally there was between Johnston and Sherman, who had developed a mutual respect during the fighting, to an agreement that also included political agreements for the south; However, these were not accepted by the Union government, so that it ultimately remained with the military agreements. Nevertheless, Johnston had been able to negotiate better terms overall than was the case with Lee. With Johnston's surrender, the war ended for all Confederate troops in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida (about 90,000 men in all). A few weeks later, the last military units of the Confederation also surrendered.

Post-war years

After the war, Johnston served as a Democrat for Virginia in the United States House of Representatives from 1879 to 1881 ; from 1887 to 1891 he was federal commissioner for the railways. He wrote the work Narrative of Military Operations (1874), in which he was very critical of Davis; he also wrote articles for RU Johnsons and CC Buels Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (1887-88).

Johnston died of pneumonia in 1891. He had attended the funeral of his former opponent General Sherman and, despite his poor health, marched in the funeral procession without his head covering to pay his last respects to Sherman. Johnston had done this before at McClellan's and Grant's funerals.

Joseph Eggleston Johnston was buried in Baltimore , Maryland; several US Army commanders against whom he had fought participated. Sam Watkins , a Tennessee infantryman who had served under Johnston, left a powerful account of him:

“But now, allow me to introduce you to old Joe. Fancy, if you please, a man about fifty years old, rather small of stature, but firmly and compactly built, an open and honest countenance, and a keen but restless black eye, that seemed to read your very inmost thoughts. [...] He was the very picture of a general. [...] He was loved, respected, admired; yea, almost worshiped by his troops. I do not believe there was a soldier in his army but would gladly have died for him. With him everything was his soldiers, and the newspapers, criticizing him at the time, said, 'He would feed his soldiers if the country starved.' […] Such a man was Joseph E. Johnston, and such his record. Farewell, old fellow! We privates loved you because you made us love ourselves. "

Both Johnston's brother Charles and his nephew John were members of Congress: Charles as a representative, John as a senator from Virginia.

rating

Johnston has often been criticized for being too defensive by trading off terrain for time. Hood even claimed that Johnston's attitude had had a negative effect on the fighting spirit of the troops under him, but that was more likely to mask Hood's failure and the extremely high losses during his time as Army Commander-in-Chief. In fact, Johnston was able to motivate his troops very well, as evidenced by the reactions to his detachment in 1864.

About Johnston's charisma and ability to motivate his subordinates, Mary Chesnut , wife of an influential southerner, who lived in Richmond and whose diaries are an important source for life in the Confederation , spoke among others . Accordingly, a relative of General Lee, who served as a colonel on Johnston's staff, described him as a superior officer in every respect. Chesnut's husband then remarked to his wife that Johnston's qualities would attract people and that he had this "gift of the gods". In addition, Johnston exuded authority and dignity, as reported by many officers around him. No one doubted his courage, his intelligence or his character. He was always loyal to his friends and although he was very dignified, he had a sense of humor and was able to laugh at himself too.

He was an organizer who also made sure that his soldiers were well fed. In the field he led the troops in an orderly manner and never got out of control in a battle. His men, grateful for not having been senselessly "burned", thanked him with a deep bond.

Johnston, who suffered few defeats (during the Atlanta campaign and at Bentonville) - a major victory as did Lee at Chancellorsville - had earned the respect of his opponents Grant and Sherman. It should not be underestimated that the numerical ratio for the Confederates in the western theater of war was generally less favorable than in Virginia, for example, even if the topographical conditions tended to favor the defenders. Nevertheless, to this day he enjoys less public recognition than Lee or Stonewall Jackson , but also than many other commanders in the South. Ultimately, his bad relationship with President Davis was his undoing, who did not have the necessary confidence in Johnston and was tempted to make the, in retrospect, imprudent decision to replace him with Hood at the critical moment. Johnston, a soldier through and through, did not recognize many a political necessity for this and was also used to giving orders, like Lee, the execution of which left a fairly wide scope. Some of his subordinates couldn't handle it.

Historians disagree on the valuation of his person. Some consider him to be the most capable commander in the South (or at least right after Lee), who recognized more clearly than others what was necessary to win the war after all: that it was not a matter of holding or conquering certain places but that the only thing that mattered was to defeat the opposing army; But he only wanted to take part in combat when it seemed advantageous to him (as with Kennesaw Mountain ). Others accuse Johnston of hesitation: he fought too seldom or too late. On many points questions remain unanswered, especially since Johnston left only a few personal testimonies.

literature

- Mark L. Bradley: This Astounding Close. The Road to Bennett Place. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC, inter alia, 2000, ISBN 0-8078-2565-4 (Bradley rated especially Johnston's actions after the Battle of Bentonville and comes to a positive assessment Johnston. Short review ).

- Thomas Lawrence Connelly: Autumn of Glory. The Army of Tennessee, 1862-1865. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge LA 1971 (Reprinted ibid 2001, ISBN 0-8071-2738-8 ).

- Gilbert E. Govan, James W. Livingood: A Different Valor. The Story of General Joseph E. Johnston CSA Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis IN 1956.

- Bradley T. Johnson (Ed.): A Memoir of the Life and Public Service of Joseph E. Johnston. Woodward, Baltimore MD 1891.

- Joseph E. Johnston: Narrative of Military Operations. Directed, during the late war between the States. D. Appleton, New York NY 1874 (edited by Frank E. Vandiver. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1959; available online in Perseus Project ).

- Archer Jones: Confederate Strategy from Shiloh to Vicksburg. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge LA 1961 (Reprinted ibid 1991, ISBN 0-8071-1716-1 ).

- Craig L. Symonds: Joseph E. Johnston. A Civil War Biography. Norton, New York NY 1992, ISBN 0-393-03058-X (and reprints), publisher's description ( Memento of September 27, 2007 on the Internet Archive ).

Web links

- Entry in the Texas Handbook (with literature)

- Civilwarhome.com: JE Johnston

- Joseph E. Johnston in nndb (English)

- Joseph E. Johnston in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- Joseph E. Johnston in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Remarks

- ^ Symonds: Joseph E. Johnston. 1992, p. 94.

- ^ Symonds: Joseph E. Johnston. 1992, p. 192.

- ↑ Connelly: Autumn of Glory. 1971, p. 360.

- ↑ See e.g. OR Ser. 1, Vol. 38, Part 5, pp. 879f. (Letter from Hood to Bragg dated July 14, 1864).

- ↑ Clifford Dowdey (Ed.): The Wartime Papers of RE Lee. Bramhall House, New York NY 1961, pp. 821f.

- ↑ See Connelly: Autumn of Glory. 1971, p. 423ff. and Symonds: Joseph E. Johnston. 1992, p. 330ff.

- ↑ OR Ser. 1, Volume 38, Part 5, p. 887 (July 17, 1864).

- ↑ OR Ser. 1, Volume 38, Part 5, p. 888 (letter of July 18, 1864).

- ↑ Connelly: Autumn of Glory. 1971, p. 424f.

- ↑ See Bradley: This Astounding Close. 2000; for a summary of Johnston's achievements during this period: ibid., p. 263 f.

- ↑ Sam R. Watkins: Co. Aytch. Maury Grays, First Tennessee Regiment or, A Side Show of the Big Show . Cumberland Presbyterian Publishing House, Nashville TN 1882, chapters 11f., (Several reprints); accessible in Project Gutenberg .

- ↑ Mary Boykin Chesnut: A diary from Dixie. Edited by Ben Ames Williams. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1980, ISBN 0-674-20290-2 , p. 429.

- ^ A traditional anecdote (Symonds: Joseph E. Johnston. New York 1992, p. 386 f.): In 1880 an acquaintance was visiting the Johnstons. The old general heard a young girl scream and looked. The girl was standing in front of a turkey that was blocking her way. Johnston asked her, 'Why don't you run away?' The acquaintance accused Johnston of this, but Johnston replied: 'Well sir, if she doesn't want to fight, the best thing to do is run away, isn't it?' Johnston's wife commented that she knew this was usually his plan, and Johnston laughed out loud.

- ↑ cf. Symonds: Joseph E. Johnston. 1992, pp. 1-6 and 383ff. For Johnston's positive assessment, cf. also James Ford Rhodes : History of the Civil War, 1861–1865. The Macmillan Company, New York NY 1917, pp. 314ff. More negative, however, James McPherson: Die for freedom. The history of the American Civil War. List, Munich et al. 1988, ISBN 3-471-78178-1 , p. 733: Before the war, Johnston was invited to go duck hunting at a planter's house, but although he was considered an excellent shooter, he never pulled the trigger. Sometimes the bird flew too high, sometimes too low, sometimes the dogs were too far away, sometimes they were too close, something always didn't fit. He was [...] afraid of missing his shot and endangering his reputation.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Johnston, Joseph E. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Johnston, Joseph Eggleston (full name); Johnston, Joseph |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American general |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 3, 1807 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near Farmville , Prince Edward County , Virginia |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 21, 1891 |

| Place of death | Washington, DC |