Nullification crisis

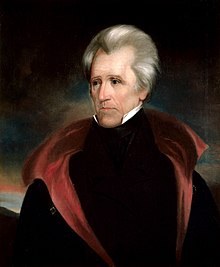

The nullification crisis of 1832/1833 was a political conflict in the United States during the presidency of Andrew Jackson . The subject of the crisis was the question of whether a single state has the right to repeal (nullify) federal laws within its state borders.

The cause of the crisis was the customs laws of 1828 and 1832, which introduced high protective tariffs for industrial products in favor of the growing industry, especially in the north , and met resistance in the agricultural south. Resistance to the tariffs and a political tradition that saw the Union as an alliance of sovereign states led to the nullification doctrine being widely accepted in South Carolina . According to her, a state could nullify laws that it considered unconstitutional and thus invalidate them. After the Customs Act of 1832 was passed, South Carolina put this doctrine into practice under the leadership of John C. Calhoun , Robert Young Hayne , James Hamilton, Jr., and other politicians. The state decided to repeal the Customs Acts of 1828 and 1832 from spring 1833 and threatened secession from the United States if the central government tried to enforce the laws by force. President Andrew Jackson, himself rather skeptical about tariffs, reacted by calling on Congress to further cut tariffs, but at the same time publicly attacking South Carolina and the nullification doctrine and threatening the use of military means. The slave states of the south did not support South Carolina in nullifying it, but made it clear that they definitely wanted to prevent a war. A compromise was finally found under the leadership of Henry Clay . It provided for the further reduction of tariffs and the withdrawal of the nullification by South Carolina.

prehistory

State or central government

Disputes over the competences of the individual states and the central government already existed before the actual establishment of the United States. The 13 colonies that broke away from the English motherland with the declaration of independence in 1776 and subsequently led the war of independence together were not a homogeneous state structure. Differences in religion, culture and economy were so significant that for the founding father John Adams it was more of a miracle that the 13 colonies agreed at all: “Thirteen clocks were made to go alike. A mechanical perfection that no craftsman had ever achieved before. "

After independence was achieved, the colonies were dominated by the feeling that excessive central state power was harmful. On the one hand, “central power” was mainly associated with England , from which they had just won independence. On the other hand, the new democracy should be directly and directly responsible. Finally, most of the colonists lived as small regional farmers who saw the government as a necessary evil and consequently wanted to keep it as small and weak and inexpensive as possible. The result of this and other political currents was the Articles of Confederation Constitution , which attached great importance to the 13 individual states but little importance to the central government of the Federation.

After the failure of Konföderationsartikelverfassung the disputed Federalists , the redesigned United States Constitution propagated, with the Antiföderalisten , the excessive power of the central government saw in the new constitution. The resulting constitution was a compromise that included significantly stronger central power. For fear that the new constitution would not be ratified, however, many passages that determined the relationship between the federal government and the states were worded very broadly and ambiguously, and no “final arbiter” was provided for the interpretation of the constitution.

After the constitution was ratified, disputes over the interpretation of the constitution increased. In 1791, for example, the first Secretary of Commerce, Alexander Hamilton, and the first Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson , a conflict arose over whether the Constitution gave Congress the right to set up a central bank . Jefferson argued that the constitution gave no explicit authority for a central bank. It is true that the constitution gives the federal government the right to pass all those laws that are "necessary and proper" for the exercise of the powers assigned to it. With necessary is meant a restrictive necessary , and a central bank is not necessary, the rights granted to the federal government can also be exercised without such a bank. Hamilton held against it that necessary in its broader meaning had to be considered useful (“useful, requisite, incidental, useful or conducive to”) and that a central bank was necessary in this sense . Hamilton was able to convince President Washington of his opinion, the first American central bank was founded on July 4, 1791.

Jefferson and Hamilton had different opinions on other policies as well, and around them the first parties of the young republic formed: the narrow-reading Democratic-Republicans around Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe, and the more centralist ones oriented federalists .

In 1796 the federalist John Adams became president. During Adams's tenure as president, relations between the United States and France deteriorated and in 1798 what was known as the quasi-war broke out . With this in mind, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts . Among other things, they allowed the president to deport or detain foreigners who came from hostile states or who were considered dangerous. In addition, the publication of "false, shameful and malicious" letters against the government and its officials has been declared a criminal act.

The Republicans saw these laws, promoted primarily by the federalists, as an attack on freedom. For Jefferson, for example, they violated the First Amendment , which guaranteed free speech and press . He and James Madison therefore drafted two resolutions for the parliaments of Virginia and Kentucky in 1798 , the so-called Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions . In the decisions of the Kentucky Parliament drafted by Jefferson, the union was referred to as a "pact" between states and central authorities. As in the dispute with Hamilton over the central bank, Jefferson argued that the federal government only had jurisdiction where it was clearly granted by the constitution. Should he also claim this competence in other areas, these resolutions would be invalid. Jefferson used the word nullification to refer to the invalidity of such laws. These, made by the individual states, was the "rightful remedy" (rightful remedy) against an ultra vires the federal government. However, Kentucky remained the only state to pass the Jefferson-written resolutions. Virginia adopted a somewhat milder version written by James Madison. This was also not signed by any other state in the USA. The two resolutions, however, were something of a wake-up call for the Democratic-Republicans, who won the subsequent elections and successively made Thomas Jefferson and James Madison presidents. Jefferson and Madison showed during their 16 years in office that they interpreted the Constitution as presidents less strictly than before; however, they never repudiated the two resolutions of 1798, which for many Democratic-Republicans remained something of an unfulfilled creed .

The “Principles of 1798” also remained unfulfilled because after the war of 1812 the United States was gripped by an overall rather centralistic mood (also referred to by the term nationalism ), which led to the measures of the so-called “ American System ”. The federal government spent more money on infrastructure measures such as canals and roads, the Second Bank of the United States was founded in 1816, and industry was promoted with protective tariffs.

Southern Discontent in the 1820s

The American consensus around the American System began to crumble in the early 1820s. When Missouri wanted to join the Union, disputes arose over the spread of slavery and the relationship between free and slave-holding states, which led to the Missouri Compromise . The Negro Seamen Law , passed by South Carolina in 1822 for fear of slave revolts, also caused a stir . Under this law, colored crew members of ships that called at the ports of South Carolina had to be detained in prison until their ship left. The Federal Attorney General , William Wirt , called this law in 1824 unconstitutional. The South Carolina Senate officially opposed this opinion; the right of a slave state to protect itself from rebellion takes precedence over all laws, treaties and constitutions.

The political conflicts were exacerbated by massive economic problems in the south. In 1819 there was a stock market crash , which subsequently hit mainly the south and here especially South Carolina. Numerous plantations were encumbered with high mortgages, which were now due as a result of a banking crisis . In addition, the soils of South Carolina were depleted after many years of cultivation, and strong competition arose with the young Southwest states with their fresh, high-yielding soils. The southwest states had not yet fully developed their agricultural land and in the face of the mortgage crisis had access to larger areas of undeveloped, fresh land, an option that did not exist in "old" South Carolina. Several hurricanes also hit the east coast of the United States in the early 1820s, adding to the problems facing planters in South Carolina. In the end, South Carolina was hit more than any other state by the economic crisis. Numerous planters emigrated, in the 1820s and 1830s the state lost 200,000 inhabitants (including slaves).

In the eyes of the residents of South Carolina, the tariffs that have prevailed for several years have been an important reason for their economic problems. On the one hand, customs raised the prices of protected goods (such as iron goods and fabrics) to a level above the world market price, so that consumers had to pay more for them. In addition, it was feared that import duties on fabrics would reduce the demand for them and thus also the demand for cotton. George McDuffie , a South Carolina congressman, formulated the "40 bale theory" that a 40% inch is about the same as taking 40 out of 100 bales of cotton from any planter . The political conflicts over slavery and economic worries created a climate of excitement in South Carolina. Influential South Carolina politician John C. Calhoun , who had previously advocated a more national program with protective tariffs and infrastructure measures, was faced with increasing competition from politicians who demanded greater consideration of the rights of individual states. As a result, Calhoun changed camp, so to speak, and developed a theory of states' rights that went even further than that of his political rivals.

General dissatisfaction with United States politics was not a phenomenon confined to South Carolina; the south as a whole became unhappy with the political situation during the 1820s. After the 1812 War, most southerners had supported the Democratic-Republican nationalist-republican policies and the American system . After the Missouri Compromise, however, there were growing reservations about too strong a central power and the fear that this central power could be controlled by interests harmful to the south. As a result, politicians, especially in the Southeast, increasingly turned against the constitutional jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, saw protective tariffs and infrastructure measures (which they, like Calhoun, had supported by the majority in the 1810s) and openly wondered whether their region still had a future of the Union. However, the South as a whole could not agree on how to confront the newly identified threat.

In 1824, a nationally minded New England politician, John Quincy Adams, was elected president. He defeated his previous party colleague Andrew Jackson . As a result, spending on infrastructure increased, cotton prices collapsed in 1826 and the South was angry about the Customs Act passed in 1824. Resistance to the American system was thereby increased, especially as concerns about slavery increased. A broad interpretation of the constitution was seen more and more as a threat to the “special institution” of the South. Virginia politician John Randolph of Roanoke summed up this concern when he said that a Congress that could build a road would also be able to free every slave in the United States.

The choice of Jackson

There was some calming for the south in 1828 when Andrew Jackson won the presidential election against John Quincy Adams and moved into the White House in 1829 . Jackson, a hero of the 1812 War and founder, was a supporter of the Jeffersonian Principles, of enormous expansion of democracy, and had a moderate election manifesto whose main goal was to reduce the debt burden. The faction he founded out of the Democratic-Republican Party (later the Democratic Party ) had a congressional majority since 1826. Because of his origins and his principles, he was considered the first man of the people in the office of president. With regard to customs, he wanted to find a “fair middle ground”. Jackson found widespread support: classic Democratic-Republicans for whom Adams's centralist measures went too far; Voters and politicians from the western states who hoped for a renewal of the "Principles of 1798" and the ideals of Thomas Jefferson and also more radical advocates of the individual states from the south. The latter put together with John Calhoun Jackson's candidate for vice-president. This and the fact that Jackson came from the south and kept slaves himself gave this group hope that he would become “their” president. A weighty difference between Jackson and his running mate Calhoun, however, was that Jackson, as the founder of the first modern party in the world, had a clear, broad-based democratic orientation, while Calhoun was more elitist .

Indeed, there was some appeasement in the South in the early years of Jackson's tenure. The newly appointed Attorney General for Georgia declared the Negro Seamen Law to be constitutional, and Jackson supporters from both North and South in Congress voted for the South position in other slavery resolutions. Jackson also supported the states there in driving out the Indians living in Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama . In 1830, Jackson also made use of his right of veto , thereby ending a bill for further federal infrastructure measures. Only on the customs question could Jackson not give in; The federal government needed income for the debt reduction he advocated, and Jackson also had to respond to his supporters in the north of the country, who would not have supported an excessive reduction in tariffs.

The Customs Act of 1828 and the Nullification Doctrine

| year | Federal income from customs duties |

Total value of American imports |

quotient |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 13.0 | 72 | 18.1% |

| 1822 | 17.6 | 92 | 19.1% |

| 1823 | 19.1 | 87 | 22.0% |

| 1824 | 17.9 | 90 | 19.9% |

| 1825 | 20.1 | 106 | 19.0% |

| 1826 | 23.3 | 95 | 24.5% |

| 1827 | 19.7 | 90 | 21.9% |

| 1828 | 23.2 | 97 | 23.9% |

| 1829 | 22.7 | 83 | 27.3% |

| 1830 | 21.9 | 79 | 27.7% |

| 1831 | 24.2 | 112 | 21.6% |

| 1832 | 28.4 | 112 | 25.4% |

| 1833 | 29.0 | 119 | 24.4% |

| 1834 | 16.2 | 140 | 11.6% |

| 1835 | 19.4 | 166 | 11.7% |

| US customs revenue and total imports All figures in millions of US dollars |

|||

In fact, Jackson's supporters from North and South could not agree in Congress in 1828; Instead, the centralist supporters of Adams' and the northern partisans of Jackson came together, both of whom advocated protective tariffs and jointly passed a tariff law known in the south as the " Tariff of Abominations " . The Customs Act of 1828 increased the import duties for numerous goods, the ratio of federal customs revenue to total imports rose from around 22% in 1827 to more than 27% in 1829. From the point of view of Calhoun and his followers, the attempt was made to defeat the customs by democratic majorities to get rid of, failed; Other measures now had to be taken to protect their minority interests. That same year, South Carolina asked Calhoun to explain in writing whether and how a state could nullify a federal law. Calhoun, wrote the South Carolina Exposition and Protest , although his authorship was kept secret for the time being.

Calhoun's aim was to clearly but calmly explain the position of the nullifiers, to prevent rash measures and at the same time to form a political basis for the withdrawal of the customs law. Calhoun argued that tariffs designed not to generate revenue but to protect certain industries are unconstitutional:

It is true that the third section of the first article of the Constitution authorizes Congress to lay and collect an impost duty, but it is granted as a tax power for the sole purpose of revenue, a power in its nature essentially different from that of imposing protective or prohibitory duties […] The Constitution grants to Congress the power of imposing a duty on imports for revenue, which power is abused by being converted into an instrument of rearing up the industry of one section of the country on the ruins of another. The violation, then, consists in using a power granted for one object to advance another

“It is true that the third paragraph of the first article of the Constitution empowers Congress to collect and collect an import duty, but this is designed as a tax authority whose sole purpose is revenue, a mandate that is completely different in nature from those of raising protectionist or obstructive tariffs. […] The Constitution gives Congress the power to impose an import tariff to generate revenue, a power that is abused when tariffs are used as a means of abandoning the industry of a part of the country To promote someone else's expense. The breach of the constitution consists in using the power granted for one goal to achieve another goal. "

Calhoun went on to explain why the current tariff system favors the industrialists of the north and places a double burden on the south: "The import duty, which is largely paid for by our labor, enables them to sell to us at higher prices." The American system therefore saw Calhoun as a system that imposed the majority of the country on a minority; in such situations political representation is not enough to protect the minority. With its separation into federal and state powers, the constitution provides protection against such situations: “The powers of the central government are listed separately and delegated in detail; and all powers that have not been explicitly delegated [...] expressly belong to the states or their peoples. ”The result is two separate areas of power - central power and individual states with their own governments and powers. Sovereignty, however, only belongs to the individual states and their peoples, they had created the constitution and can change it again with a three-quarters majority. According to Calhoun, the individual states therefore have a veto right against the central authority's pretensions of authority, and this veto right also serves to protect the minority from the majority: “Can the central power, on the other hand, invade the rights reserved to the states? Every state is given the possibility in its sovereign ability to stop such an intrusion through its veto or its interposition. "

With the Exposition and Protest , Calhoun succeeded in developing a coherent position for the abolition of a law that was controversial due to the distribution of powers. Not the Supreme Court, which was appointed and confirmed by the President and Senate, but the peoples of the individual states should have the last word on the constitutionality of a law, because in this interpretation they were the constituent power. The nullification of a law by a state would, in the view of Calhoun and his supporters, lead to the convening of a constitutional convention similar to that of 1787.

The political debate until 1832

The South Carolina Exposition and Protest also sparked renewed constitutional debate about the origin of the Union and the role of states. At one end of the spectrum were Calhoun and the South Carolina's more radical tariff politicians, the nullifiers and like-minded politicians in the South, or, in the terminology of historian David Ericson, the "Federal Republicans". For them the union was a federation of sovereign states, the residents were citizens of their respective state. The American Republic was an alliance of smaller republics, and these individual republics, the individual states, had to be protected. United States history, as read, has been an unfortunate move away from the state-centered principles of the Founding Fathers towards centralism. Of course, there were differences within that spectrum as well, and parts of this group criticized South Carolina's actions in the later crisis. There was, however, a certain consensus on the prerogatives of the individual states and the above all federal character of the Union. At the other end of the spectrum were the "nationalists"; they rejected the idea of the United States as a federation of sovereign states: it was not the states but the people who had given themselves the constitution, so that the nation as a whole had priority over the individual states. For this group, which included John Quincy Adams, Joseph Story and Daniel Webster , the Supreme Court, not the individual states, had the final say on constitutional matters.

Between the two camps stood the “centrists” so called by David Ericson. These were traditional supporters of the rights of the individual states, but they did not recognize the pure sovereignty of the individual states. Instead, they advocated the idea of “shared sovereignty”. In contrast to Calhoun, who had explicitly differentiated between powers and sovereignty in Exposition and Protest , they saw the federal government in its areas of responsibility as just as sovereign as the individual states in theirs. For many centrists, a broadly democratic, Jeffersonian attitude also played a role. The idea that a state could nullify a federal law and then only be overruled through a constitutional process with a three-quarters majority was not compatible with their ideas of democracy. Former President James Madison belongs to this group. The nullifiers claimed their position was based on the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions of 1798, but, Madison wrote to Edward Everett :

Can more be necessary to demonstrate the inadmissibility of such a doctrine than that it puts it in the power of […] 1/4 of the US - that is, of 7 States out of 24 - to give the law and even the Constn. to 17 States […] That the 7 might, in particular instances be right and the 17 wrong, is more than possible. But to establish a positive & permanent rule giving such a power to such a minority over such a majority, would overturn the first principle of free Govt

“Is it more necessary to show the inadmissibility of such a position than to put it in the power […] of a quarter of the United States, that is, 7 out of 24 states, to pass 17 states laws and even the constitution? [...] It is more than possible that the 7 could be right and the 17 wrong in certain cases. But to establish a positive, permanent rule that gives such a minority such power over such a majority would turn the first principle of free government on its head. "

Louisiana's Senator Edward Livingston also discussed in 1830 what options a single state had in the eyes of the centrists to take action against a controversial law: It could go to the Supreme Court, protest in Congress, appeal to the other states, and Incite political opposition as Kentucky and Virginia did in 1798, voters could influence their MPs, and the state could propose an amendment to the Constitution. The nullification of a law by a single state or even unilateral secession , however, was not permissible for Livingston, except in extreme cases.

President Jackson also had to deal with nullification and the protective tariff issue. As a senator in the 1820s, he had been fundamentally open to tariffs, and even now he saw tariffs as helpful in protecting industries that would be necessary in the event of war. It was also clear to him that the Constitution definitely gave the federal government the right to demand tariffs with a protectionist character. However, he rejected excessively high protective tariffs, and during his presidency he saw tariffs (apart from considerations of defense policy) primarily as a source of income for reducing national debt. However, since these would be paid back around the mid-1830s, Jackson was in favor of lowering tariffs thereafter. In his view, the political debate about tariffs was at times irrational. In his annual address to Congress on December 6, 1830, he said: "The effects of the current tariff law are undoubtedly exaggerated, both in its evils and in its virtues." In 1829, he proposed that Congress exempt products from duty which were not in competition with American products; Congress complied with this proposal in 1830 by reducing tariffs on cocoa , tea , coffee and molasses . Jackson's position on nullification was clearer than that on customs. His firm belief in the democratic majority principle made it impossible for him to accept the nullification of a law passed by the majority in Congress. In February 1831 he wrote to South Carolina nullifier Robert Young Hayne :

For the rights of the state, no one has a higher regard and respect than myself, none would go farther to maintain them: It is only by maintaining them faithfully that the Union can be preserved. But how I ask is this to be effected? Certainly not by conceding to one state authority to declare an act of Congress void [...] far from it, there is a better remedy [...]. If Congress, and the Executive, feeling power, and forgetting right, shall overleap the powers the Constituion bestow, […] the remedy is with the people […] thro the more peaceful and reasonable course of submitting the whole matter to them at their elections [...] Such abuses as these cannot be of long duration in our enlightened country where the people rule.

“Nobody has a higher respect and a higher respect for the rights of the state than I do, nobody would go any further to preserve them. Only by keeping it faithfully can the Union be kept. But how, I ask, can this be done? Certainly not by giving a state the power to invalidate a law of the Congress […] far from it, there is a better solution […]. When the Congress and the Executive, feeling power and forgetting what is right, extend their power over what the Constitution grants them [...] the remedy lies with the people [...] and in the more peaceful and sensible course of putting the whole matter before them in their elections . [...] Such abuses cannot last long in our enlightened country, where the people rule. "

The issues raised and clarified by the Exposition and Protest and the protective tariff issue also played an important role on other issues; In 1830 the Senate debated a restriction on the sale of federally owned land. Daniel Webster represented the nationalist position, South Carolina's Senator Robert Young Hayne that of the nullifier. The above-mentioned Edward Livingston presented the view of the centrists in this debate. In 1830, the “radicals” who advocated nullification won a slight majority in South Carolina and, with James Hamilton junior, became the governor.

The Customs Act of 1832

Due to the good economic development and reluctance of the Congress in the spending policy, it was foreseeable that the national debt would be repaid in full from 1833. Under the Customs Act of 1828 this would have meant that the federal government would have received large surpluses afterwards. To prevent this, a new customs law was necessary. For Jackson and his Treasury Secretary, Louis McLane , this was an opportunity to significantly lower tariffs while still maintaining protection for industries relevant to security policy. The protectionist Henry Clay, on the other hand, proposed drastically lowering tariffs on a large part of goods, but leaving them at the current high level for industries in need of protection, which in the end would have increased protection for high-duty industries. Such an approach would have caused outrage in the south. While revenue tariffs were legitimate even by narrow interpretations of the constitution, the majority of southerners opposed protective tariffs; But how should one see a customs authority, whether it is used to generate income or to protect? Since the spring of 1832, the nullifiers had found a new answer to this: A revenue tariff should be as simple and fair as possible and therefore provide for the same tariffs for all goods. The more unequal a customs law, the more it preferred some goods and disadvantaged others, the more pronounced its protective character would be in this reading. The bill proposed by Clay would have led to even more resistance in the eyes of many politicians. Instead, John Quincy Adams worked closely with Louis McLane to draft an alternative bill. It planned to lower the tariffs on a large part of the products, abolished the “minimum value principle”, but kept the tariffs on cotton, fabrics and iron at almost 50%. With this draft, the average duty on products to be declared returned to 33% and thus to the level of 1824.

Historian Daniel Ratcliffe sees this bill as the “true compromise tariff”, and it was actually adopted by a large majority: it received around two-thirds of the votes in the Senate and House of Representatives , with a majority of MPs in both the free and slave states . Of the slave states, only the representatives of Georgia, South Carolina and Louisiana (these, however, for different reasons) voted against the law by a majority in the House of Representatives. The opposition to the law was generally limited to the extremes, to radical tariff opponents and iron protectionists. After this compromise, the conflict seemed to have been averted for the time being. A Pennsylvania MP wrote that nullification was now "dead and buried," the unionists in South Carolina seemed invigorated, and Jackson was pleased with the law, which was a defeat for both extreme protectionists and nullifiers. In June 1832, Jackson vetoed the charter for the Second Bank of the United States, showing that he was still in the Republican tradition of narrow constitutional interpretation, and won an overwhelming majority in the South in the 1832 presidential election .

The nullification

In the course of 1832, however, it became apparent that Jackson had underestimated both the nullification sentiment in South Carolina and overestimated the effects of tariff reform. Support for nullification had grown in South Carolina since 1829, and in 1831 the radical nullifiers, led by George McDuffie and Governor James Hamilton, began their political campaign for the annulment of the Customs Act. The first goal here was to win a two-thirds majority in the elections in South Carolina in 1832, because this was necessary in order to convene a convention, which could then resolve at most a nullification. McDuffie gave a speech on May 19, 1831, in which he underlined the unconstitutionality of the Customs Act of 1828 and even called for violence and revolution if necessary to defend the sovereignty of South Carolina. Even the Customs Act of 1832 did not change the attitude of the nullifiers. With its 50% duty on iron, fabrics and cotton it still had a high protective tariff-based, as the politicians of South Carolina were dissatisfied, dissatisfaction, probably belonging to the since 1830 noticeably stronger role for the abolitionists contributed to the north. Another role was played by the broader questions of the nullification doctrine, and the implications it had for constitutional interpretation and the rights of individual states. With a nullification of a customs law that was unconstitutional from South Carolina's point of view, it was not only possible to attack customs as such, but also to find an answer to the problem of unconstitutional decisions by Congress. A debate about tariff nullification would, in the words of James Hamilton, be an outpost battle, and a victory would secure the citadel proper.

Jackson's moderate and hesitant attitude towards customs put his Vice President Calhoun in distress. The supporters of nullification were also divided into two camps: For the radicals, nullification was only one step on the road to ultimate secession, to complete detachment from the United States. A moderate wing, on the other hand, saw nullification as a means of preventing this secession: even a nullifying state remained a member of the United States. As a representative of the moderate wing of the nullifiers, Calhoun had been able to reassure the more radical supporters of the doctrine around George McDuffie and Governor Hamilton by saying that Jackson would advocate a tariff reduction and that an immediate nullification was therefore not necessary. The only hesitant tariff reduction put him under considerable pressure. There had also been other differences between Calhoun and Jackson between 1828 and 1832, for example with regard to Jackson's policy against the Second Bank of the United States , which Calhoun did not share. In addition, Calhoun hoped to inherit Jackson in the White House, but Jackson preferred Martin Van Buren . The result was an increasing estrangement between the president and vice-president. Increasing political pressure on Calhoun eventually caused him to abandon his moderate stance. In late July 1832, he published the Fort Hill Letter , welcoming nullification.

The elections in the fall of 1832 brought Jackson a national victory, but at the same time finally showed that nullification was anything but dead; South Carolina was one of the few southern states that did not vote for Jackson. The state could not vote for Jackson's most promising opponent, the protectionist Henry Clay, either, so that the electoral votes of South Carolina went to Virginia Governor John Floyd instead . In addition, in October in South Carolina, the Nullifiers won the two-thirds majority they needed to convene a state convention. This then happened within two weeks of the opening of the parliamentary session. In the convention, which met for the first time on November 19, 1832, the nullifiers spoke as expected; Governor Hamilton presided over and convened a committee of 21 members to draft a declaration of nullification, including Robert Hayne, George McDuffie, Robert Rhett and Robert J. Turnbull . As early as November 22nd, the commission presented several documents to the Convention, including an Ordinance of Nullification , an address to the people of South Carolina and an address to the people of the United States. Overall, the injustices of the customs system were shown again. A return to a mere revenue duty of 12% on all goods is acceptable. The United States was given February 1, 1833; If nothing happened on the customs issue by then, the customs laws of 1828 and 1832 would be declared invalid and the South Carolina Parliament would do everything to prevent the enforcement of the laws on its territory. Should the federal government react to this nullification with violence, the declaration threatened secession, the exit from the United States. The address to the people of the United States formulated it even more drastically: "We would infinitely prefer that the national territory should be a cemetery for the free instead of a living space for slaves." The documents prepared by the commission were adopted with 136:26 votes. Three days later, parliament decided to set up a volunteer army of 12,000 men. Robert Hayne became the new governor, his post in the Senate should take Calhoun, who returned the office of vice president.

The public debate about nullification

Jackson's reaction: Proclamation and Force Bill

The declaration of nullification enraged Jackson. He reportedly told a congressman that South Carolina can talk as much and make as many decisions as it likes, but if a drop of blood is spilled while opposing a federal law, he will be the first nullifier he can get his hands on hang the first tree he can find. And Martin van Buren, who had succeeded Calhoun as vice president, later said Jackson had at times had an almost passionate desire to invade South Carolina himself and arrest Calhoun, Hayne, Hamilton and McDuffie. Jackson saw the nullifiers as a conspiracy against the American Republic, nullification for him was the same as secession or high treason. His reluctance was mainly focused on Calhoun, whom he viewed as an ambitious demagogue who had led Hayne, Hamilton, and others on the wrong path.

Jackson's political reaction is portrayed as a mixture of " carrot and stick ", although the "carrot" was not intended for the nullifiers but for the other southern states. The nullification of South Carolina was based on the claim that the minority must be protected because the Congress majority would not lower tariffs. To show this as false, Jackson asked Congress in 1832 to lower tariffs further. Jackson gave up his reluctance to do so and proposed a significant reduction in tariffs and the abandonment of protection. With this policy he wanted to isolate South Carolina politically, but had to accomplish a balancing act, since many of his supporters in the north were still in favor of protective tariffs. Jackson also supported Georgia and Alabama in their Indian policy against the Cherokee and Creek , so that they also did not take the side of the nullifiers in the episode. The “whip” in Jackson’s policy was intended for the nullifiers, and against them he relied primarily on power. His aim was to militarily impress and frighten the nullifiers. He sent reinforcements to South Carolina Customs, alerted the Navy, and sent arms to the loyal Unionists in South Carolina. He also ordered the customs officers in South Carolina's port of Charleston to occupy Fort Moultrie , which is located at the entrance to the port, and from there to collect the customs using customs cutters. Merchants who refused to pay customs should have their merchandise confiscated and kept at Fort Moultrie. Since South Carolina did not have its own warships, it could not oppose this type of customs collection. In the same way, a shipment of sugar belonging to South Carolina's former Governor Hamilton, which was to be imported into Charleston, was also confiscated.

On December 10, 1832, the president also made a proclamation to the people of South Carolina. He set out his view of nullification, describing it as “incompatible with the existence of the Union, explicitly contradicted by the text of the Constitution, not empowered by its spirit, inconsistent with any principle on which it was founded, and destructive to the great goal , for which it was made. "The compact theory , according to which the union is only an alliance of sovereign states, he rejected and for this reason also contradicted the right of secession claimed by South Carolina:" To say that a state as he wants from Leaving the Union is the same as saying that the United States is not a nation. ”Secession is not a constitutional right, but merely a revolutionary remedy for extreme oppression. After these moral and legal considerations, Jackson's proclamation then warned the “misled” citizens of South Carolina of the consequences of their actions. The state stands on the brink of insurrection and betrayal, and secession, contrary to the assurances of its representatives, is not a peaceful act. As President, he will stand by his task, enforce the laws of the Union and maintain the Union. If war broke out, however, it would not be triggered by an offensive act by the United States.

On January 16, Jackson also asked Congress to pass a bill known as the Force Bill . In addition to additional powers and freedoms in the collection of customs duties, paragraph 5 of the draft authorized the President to take military action if necessary in the event of resistance to a federal law.

Political debate in the winter of 1832/33

Jackson's proclamation was remarkable. In particular, his constitutional statements, in which he gave the Union precedence over states, were, in the words of Jefferson biographer Merrill D. Peterson , "closer to the Webster School than anything Jeffersonian" and thus surprised nullifiers and more moderate followers of the rights of the individual states alike. In the Democratic Party, the proclamation created a lot of confusion and unrest, as it seemed like a departure from the old Jeffersonian principles that Jackson had previously advocated. The strong words against secession critics were also found among southern democrats. Although the southerners, with the exception of South Carolina, regarded the nullification as unconstitutional, the possibility of secession was clearly given for them. The Virginia legislature, for example, approved Jackson's anti-nullification stance and sent an emissary to South Carolina to divert the state from its course. At the same time, however, it passed a resolution according to which every state has the right to leave the Union in a legal and peaceful manner. Virginia's Democratic Senator John Tyler also considered quitting the party. The fact that the proclamation was widely acclaimed by centralist politicians like Daniel Webster added to the political worries of the Democrats, and for many South Democrats the power component in Jackson’s policy on nullification was too strong, in their eyes the president was too little on top Compromise. In particular, the sections of the Force Bill , which were more focused on military power, added to this unease: the nullifiers were able to win over a large part of the southern senators when they tried to postpone the debate on the law. This attempt was ultimately unsuccessful, the Senate voted 30:15 for immediate deliberation. Since the South had almost unanimously voted for an adjournment, it represented a victory for the nullifiers. It turned out that Jackson's harsh reaction unsettled his own supporters and strengthened the nullifiers. Instead of defending the legitimation of the nullification doctrine, which is nowhere really recognized except in South Carolina, they could concentrate on Jackson's reaction, which they portrayed as a departure from the rights of the individual states with downright despotic features. At the same time, she was doing this more cautiously, because in order to gain further support, they had to show that their doctrine was truly peaceful. Laws to enforce customs nullification were therefore only formulated very carefully. On the initiative of James Hamilton and William C. Preston , a meeting in Charleston also decided that the declaration of invalidity, which was originally intended for February 1, 1833, should not come into force until early March after the end of the congressional session.

At the end of January 1833, the situation was quite mixed up. Parliaments in several northern states had passed resolutions supporting Jackson's proclamation, including Pennsylvania , Illinois , Indiana and Delaware . The south had shown an ambiguous reaction: although the majority of the southerners rejected South Carolina's declaration of nullification, they did not approve of Jackson's proclamation and hoped for further tariff cuts. The North Carolina Parliament z. B. in a resolution described nullification as "revolutionary in character" and "subversive to the United States Constitution," but also stated that a majority of its citizens considered protective tariffs unconstitutional. Parliament also expressed its hope for a peaceful settlement. Similar resolutions were passed by the Alabama and Mississippi parliaments , and Tennessee reaffirmed its support for state rights by rejecting nullification but referring again to the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions of 1798. None of the four states expressed their approval of Jackson's proclamation in their resolutions, as Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana and Delaware had done. South Carolina had received no support for the nullification, but Jackson's course, which many Democrats perceived as too harsh, ensured that the president could not be too sure of his position either. The southern states in particular protested against too harsh intervention, and a military confrontation between the federal government and South Carolina would have amounted to a civil war .

The confused political situation was also evident in parliament. Little progress was made in the passage of the Force Bill , and parliament also voted against Jackson's wishes on two other bills that were negligible for nullification. Jackson's push to cut tariffs also came to a standstill: a tariff bill was drafted with the close cooperation of his finance minister Louis McLane. The draft known as the Verplanck tariff (after Gulian C. Verplanck ) envisaged a return to the tariff level of 1816 within two years, but not abandoning the protection principle. This corresponded to a halving of tariffs within two years. However, the draft met with broad opposition from various political groups. Protectionist politicians had gained self-confidence through Jackson's proclamation and therefore did not want to make concessions to the nullifiers. They also feared that such a relenting due to the threat of violent resistance would make the federal government open to blackmail in the future and open the door to further threats. Democrats from the north, whose voters were basically in favor of high tariffs, were also more likely to oppose the Verplanck draft and tried to increase tariffs on individual products. In the end, the nullifiers and their allies also rejected the draft: They demanded a departure from the principle of protection and, in return, were prepared to accept a less abrupt reduction in tariffs than under the Verplanck draft. In mid-January 1833 it was therefore clear that the Verplanck draft would have no chance in Congress.

The compromise

Clay's suggestion

In February 1833 something like a standstill had set in. South Carolina was isolated on the nullification issue, with opposition to the doctrine both inside and outside the state. February 1st passed without any customs nullification measures. At the same time Jackson had also suffered defeats, the Force Bill was practically postponed, the Verplanck draft failed. New York Democrat Silas Wright wrote that there was “all confusion and uncertainty in Congress,” and Missouri's Senator Benton was amazed at the strange political constellation: a president who was re-elected at a ratio of 4: 1, but the party was in both houses of Congress in the minority.

What was needed was a compromise that allowed everyone involved to save face. That was the hour for Henry Clay. After his severe defeat in the presidential election, the senator had hardly participated in the nullification debate. Now the protectionist and architect of the American System has been asked by industry representatives to ensure that the uprising in the South ends and that a certain protective tariff continues. At the same time, more and more southerners were also trying to help South Carolina by finding a solution that was honorable to the nullifiers. So it came about that the two extreme ends of the political spectrum, the centralist protectionist Clay and the nullifiers around Calhoun, sought a compromise solution together. As surprising as this may seem at first, there were a few points of contact between Clay and Calhoun: Both were political rivals of Jackson, and both had worked together successfully in the 1810s. After that they had split politically, but their good personal relationship remained. Calhoun was also willing to compromise, as he wanted to prevent the secession of South Carolina, which some politicians in his home state seemed to be working towards. Unlike the more radical Nullifizierern as McDuffie he saw secession as far as possible to avoid only a last resort to.

Clay realized that the nullifiers were more concerned with the principle of protection, with unevenly high, discriminatory tariffs than with the absolute level of tariffs, and that they did not want a compromise from which Jackson could draw any political profit. For this reason, he presented a bill on February 12, 1833, which was based on the Customs Act of 1832 and set the goal for 1842 that no tariff should be higher than 20%. All tariffs that were higher than 20% under the law of 1832 were to be gradually reduced in the following years, initially at smaller and later at larger intervals. In addition, more goods than before have been completely exempted from customs duties. Under this tariff there was still a clear protection until 1842, and the protection principle would not be completely abolished in 1842, because within the 20% discrimination between products should still be allowed; nevertheless, the 1842 tariff would look much like the revenue tariff demanded by the opponents of protectionism. Clay's compromise became mutually acceptable.

Parliamentary implementation

However, the implementation of the law was not guaranteed: In particular, the eastern wing of Clay's own party around Daniel Webster and John Quincy Adams refused to make any concessions to South Carolina, and Jackson's Democrats were also skeptical of one of Calhoun and Clay, their big rivals of the President, negotiated compromise. Jackson himself was also dissatisfied, on the one hand because the compromise tariff did not go far enough in his eyes (under the Verplanck draft the tariffs would have fallen significantly more quickly), and on the other hand because the Force Bill had still not been adopted. For Jackson, as for most other politicians who were “centrists” or “federal republicans” (in the Ericsson terminology above), a compromise was unthinkable unless it included a resolution that was the South Carolina's view that the Union is a mere federation of sovereign states contradicted. Accepting the compromise without the Force Bill would mean accepting South Carolina's constitutional interpretation, the compact theory . For this reason, the Force Bill was passed in the Senate on February 20 . 32 senators voted for him, only John Tyler from Virginia voted against. Senators from South Carolina, North Carolina, Mississippi and Alabama stayed away from the vote, as did those from Kentucky and Missouri and Samuel Smith from Maryland.

This ultimately secured the approval of Jackson and his Democratic-Republicans for the compromise tariff. Difficulties arose when Delaware's influential protectionist Senator John Middleton Clayton called for an amendment to the Customs Act that goods should be cleared according to their value as determined in the port of the United States. As a result, the dealers could not reduce the tariffs by falsified, understated valuations in their favor. added to the value of the goods to be declared. This represented an increase in the tariffs paid in real terms of possibly up to 10 percentage points. Calhoun initially opposed this, but Clayton made it an indispensable condition for his approval, so that the Senator of South Carolina finally gave in. At Clayton's express request, Calhoun also voted for the bill in the Senate and did not abstain as he did on the Force Bill . This secured the Senate majority for the Customs Act, and Clay also managed to organize a majority in the House of Representatives: on February 26, it was passed with 119 to 85 votes. One final problem arose when the nullifiers in the House of Representatives threatened to postpone the Force Bill decision . This was resolved, however, when the Senate decided not to adopt the Customs Act until the House had approved the Force Bill . On March 1, the Force Bill was passed in the House of Representatives at 111:40, and on the same day the Senate voted 29:16 for the customs law. Clay and Clayton also managed to get Calhoun to support a law on the same day after the proceeds of the sale of the state were to be distributed among the states in the future. This would have made customs the only source of income for the federal government. However, this law was thwarted by Jackson using a pocket veto .

After the Force Bill and the compromise tariff had been passed, the nullification convention finally met again in South Carolina. Certainly some radicals like Thomas Cooper and Robert Rhett were disappointed by what they saw as the meager result. Calhoun, who had rushed from Washington to South Carolina after the end of the congressional session, was finally able to convince the majority. The Convention described the passed customs law as honorable and withdrew the nullification of the customs laws of 1828 and 1832. As the final act of resistance, however, he nullified the now obsolete Force Bill .

Importance and evaluation

Historians diverge as to the outcome of the crisis. Arthur M. Schlesinger saw the crisis in his 1945 biography of Jackson as a great success of the president: "Through his masterful statecraft, Jackson had asserted the sovereignty of the Union." The nullification had proven to be similar to the rebellion and played subsequently in the political Discourse no longer matters. Jackson's proclamation has caused unease among his supporters who advocate state rights; Schlesinger saw this, however, limited to a small circle, the majority of the people were on the fundamental question - that of the unity of the Union - on Jackson's side. Even William W. Freehling saw the Nullifier to the losers of the crisis: In 1833, the "minority veto" was off the table, the majority principle had been victorious. The argument that protectionist tariffs are unconstitutional was also off the table. The compromise tariff that was negotiated had dedicated, high protective tariffs that were only reduced in very small steps over nine years from 50 to 20 percent, and whose constitutionality was not questioned. On the question of the tariff, the compromise that was ultimately accepted fell far behind the Verplanck tariff proposed by the Democrats; under this the tariffs would have dropped to 20 percent within 2 years. In addition, the compromise postponed the end of protection by nine years. However, no one could oblige a congress that would meet nine years from now to adhere to the 20% tariffs. In fact, they did not stay at this level for long: After the economic crisis of 1837 , the federal government had too little income, so that after the expiry of the Compromise Customs Act of 1842, an increase was again up for discussion. In the meantime, the United States' Second Party System had emerged, with the majority Whigs from both north and south voting for a 35% tariff, very similar to the South Carolina tariff law of 1832. Outcry for a new nullification remained isolated and without consequences.

On the other hand, the nullifiers had also had some successes: they achieved a reduction in tariffs and no one asked them to abandon the constitutional interpretation on which the nullification doctrine was based. They also managed to expand their rule in South Carolina in the following years by portraying unionist politicians as disloyal to the state. Calhoun in particular was also able to use the crisis to gain more political weight in his home state. Support for him in South Carolina was significantly greater in the 1830s than it was in the 1820s. In addition, it is argued that the passage of the Force Bill and the Compromise Customs Act most closely matched the view of the “centrists”, who saw the Union as neither a pure alliance nor a pure nation, but advocated concepts of dual sovereignty. The final evaluations therefore range from a severe defeat for the nullifiers and a victory of Jackson over a success of the centrists who advocate moderately for the individual states to successes for the nullifiers.

In keeping with this ambiguous judgment, historians see various consequences for the constitutional "schools of thought" in the United States. The compact theory , according to which the union was a federation of sovereign states and which granted the individual states wide rights up to and including secession, had been fully thought out and formulated at the latest since the 1820s and had found supporters. However, only through the nullification crisis succeeded in centralizing opponents of this theory to formulate a coherent counter-position, which denied the right to secession, arguing that states an "eternal connection" (perpetual union) had been received. Examples of this line of argument are the Senate speeches by Webster and Livingston in 1830, a speech by John Quincy Adams in 1831, the Commentaries on the Constitution by Joseph Story in 1833, and also Jackson's proclamation. The compact theory was so during the nullification crisis with the concept of perpetual union a formulated state theory opposite position. On the other hand, the nullification crisis also gave a boost to the idea of secession. Before the crisis, it was primarily a rhetorical device that was sometimes used and that was used regardless of political beliefs or regional origin. In the course of the nullification crisis, however, the law of secession was repeatedly linked with the rights of the individual states and also gained supporters who were critical of the actual nullification. The fact that the final compromise did not contain any provisions or resolutions on secession contributed to this development. Secession became an important political and ideological issue for the next 30 years.

Several historians argue that Jackson misunderstood the crisis that lay ahead. He saw the dispute primarily as a conspiracy against American Republicanism with a power-hungry demagogue Calhoun at its head. In doing so, he overlooked the fact that the crisis was an expression of real fears of the slave-holding South, which feared a northern majority. For historian Richard B. Latner, Jackson ironically managed to find a successful way out despite this misinterpretation of the crisis. Richard Ellis, on the other hand, sees Jackson's defeat in the crisis. The Force Bill was finally adopted, but in the end the president had to give in and agree to a compromise over which he had little influence. While South Carolina had been isolated about nullification, the south and much of the rest of the country had shown their reluctance to a military solution and their fear of civil war.

What is clear is that the nullification crisis brought the Union to the brink of civil war and "shook its core". It was seen in retrospect as a “prelude to the Civil War, ” as part of a development that began with the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and eventually led to the Great War via the Nullification Crisis and the Crisis of 1850 . According to Jackson's proclamation on December 10, 1832, the Calhoun biographer Charles M. Wiltse even considered the Civil War “inevitable”. However, modern studies on the crisis emphasize that there was less “South” against “North” and “individual states” against “centralism”. The nullification crisis, with its main adversaries Calhoun and Jackson, was more of a dispute between different mindsets, both of which advocated state rights. One, represented by Calhoun and the Nullifiers, saw the union as a federation of sovereign states and secession as a constitutional right and wanted to protect the interests of minorities, the other saw the United States as an eternal union, perpetual union and defended the majority principle. The fact that no other southern state approved of the nullification also makes it difficult to view the crisis as a pure north-south conflict. The rest of the South had been politically satisfied in the years before and during the crisis and had not yet given up belief in the majority principle; In contrast to South Carolina, he relied on fighting customs as part of the normal political process. The south maintained this course even after the crisis: there was no separate party system in north and south. Free and slave states did not oppose each other, but shared their sympathies both for the Whigs and the Democrats. For another generation, the South saw the constitutional process as its best representation of interests rather than minority veto and secession. In the longer term, however, the crisis and its outcome accelerated the polarization of the United States into slave and free states; The nullification crisis, although Jackson never understood it in this way, was primarily an expression of the fears of the southern slaveholders, who feared a majority in the north who were skeptical of slavery. They found protection against this majority in the principles of the rights of the individual states, in nullification and later in secession, and this basic problem was not solved either by the compromise of 1820 or by the tariff compromise that had now been found. This way of thinking was pushed forward in the following decades, while at the same time opposition to slavery grew in the north and north and south drifted further apart, until the crisis came even greater in 1860/61.

swell

- State Papers on Nullification. Dutton & Wentworth, Boston 1834 (available online on Google Books ).

literature

- Richard E. Ellis: Union at Risk. Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights and the Nullification Crisis. Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-506187-X .

- David F. Ericson: The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism, and the Force Bill Debate. In: Journal of Southern History. Vol. 61, No. 2, 1995, pp. 249-270.

- William W. Freehling: Prelude to Civil War. The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816-1836. Oxford University Press, New York 1992, ISBN 0-19-507681-8 (reprinted from Harper & Row, New York 1966 edition).

- William W. Freehling: The Road to Disunion. Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854. Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-505814-3 .

- Richard B. Latner: The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion. In: Journal of Southern History. Vol. 43, No. 1, 1977, pp. 19-38.

- Dennis Jonathan Mann: An entity sui generis? The debate about the essence of the EU as reflected in the "Nature of the Union" controversy in the USA. In: Frank Decker / Marcus Höreth (ed.): The constitution of Europe. Perspectives of the integration project, VS Verlag 2009, pp. 319–343, ISBN 978-3-531-15969-0

- Merrill Peterson: Olive Branch and Sword. The Compromise of 1833. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge 1982, ISBN 0-8071-0894-4 .

- Donald J. Ratcliffe: The Nullification Crisis, Southern Discontents, and the American Political Process. In: American Nineteenth Century History. Vol. 1, No. 2, 2000, pp. 1-30.

- Kenneth M. Stampp: The Concept of a Perpetual Union. In: The Journal of American History. Vol. 65, No. 1, 1978, pp. 5-33.

Web links

- Jackson's proclamation and other documents related to the nullification crisis

- Department of Humanities Computing, University of Groningen: An Outline of American History (1994): Nullification Crisis

Remarks

- ↑ Adams to Hezekiah Niles February 13, 1818, online at the Constitution Society

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 2f.

- ↑ a b Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 4

- ^ Jefferson, Opinion on the Constitutionality of Establishing a National Bank , February 15, 1791, reprinted, et al. a. in Noble E. Cunningham: Jefferson vs. Hamilton. Confrontations that shaped a nation . Bedford, Boston, Mass. 2000, pp. 51-54

- ^ Hamilton, Opinion on the Constitutionality of Establishing a National Bank , February 23, 1791, reprinted and published. a. in Noble E. Cunningham: Jefferson vs. Hamilton. Confrontations that shaped a nation . Bedford, Boston, Mass. 2000, pp. 55-62

- ^ Noble E. Cunningham: Jefferson vs. Hamilton. Confrontations that shaped a nation . Bedford, Boston, Mass. 2000, p. 62f.

- ^ RB Bernstein: Thomas Jefferson, Oxford University Press 2005, p. 93

- ↑ loc.gov: A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: US Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875 , accessed June 24, 2012

- ^ A b Bartleby.com: The Columbia Encyclopedia: Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions ( May 9, 2008 memento on the Internet Archive ), accessed July 31, 2007

- ↑ Text of the Kentucky Resolution in the Avalon Project at Yale University: Kentucky Resolution , accessed June 25, 2012

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 6; For an overview of the American System , see below. a. the website of the American Senate: Classic Senate Speeches: Henry Clay: In Defense of the American System , accessed June 25, 2012

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , 6f.

- ^ Freehling, The Road to Disunion , pp. 254f.

- ^ Freehling, The Road to Disunion , pp. 255f.

- ^ Freehling, The Road to Disunion , p. 256

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 7

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , pp 2-4

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , pp 5-7

- ↑ Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , pp. 20f.

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 13f.

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 260, p. 262

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , p 9f.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process S. 10f., Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , p.21

- ↑ Bicentennial Edition: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, available online at census.gov ( Memento of the original from June 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed June 26, 2012; Data series used: Y352–357 (Customs) and U1–25, (Total Imports of Goods and Services), to be found in ZIP folder 2, PDFs CT1970p2-08 and CT1970p2-12

- ↑ For a detailed discussion, see Frank William Taussig : The tariff history of the United States , 6th edition, Putnam's, New York 1905, pp. 86-104. Available online at archive.org

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , page 11

- ↑ For the text, see Wikisource

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 257

- ^ John Niven: John Calhoun and the Price of the Union , Louisiana State University Press, Paperback Edition 1993, p. 161

- ^ John C. Calhoun, South Carolina Exposition and Protest , 1828

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 258

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , p.15

- ^ A b Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 9

- ^ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism and the Force Bill Debate , p. 261

- ↑ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism and the Force Bill Debate , pp. 255, 260ff.

- ^ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism and the Force Bill Debate , p. 256

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 10

- ↑ Letter James Madions and Edward Everett of 28 August 1830. Available online at constitution.org

- ↑ a b Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 11

- ↑ Jackson's Second Annual Address to Congress, available online from the University of California Santa Barbara Presidency Project , accessed June 29, 2012

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 42-45

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 47

- ^ Letter from Andrew Jackson to Robert Y. Hayne dated February 8, 1831, cited in Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 45

- ^ William Freehling, Prelude to Civil War , Paperback, Oxford University Press, 1992, p. 218

- ^ A b Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , p. 12

- ^ A b c Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , p. 19

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 46

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis southern discontents, and the American political process , S. 13f.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis southern discontents, and the American political process , p.14

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 50f.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 50, p. 65

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , pp. 272f.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , S. 16f.

- ^ Freehling, Prelude to Civil War , p. 262

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 53ff., P. 62

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 66

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 74

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , pp. 276f.

- ↑ This was a compromise between radical nullifiers who wanted immediate nullification and moderates who wanted a longer period. See Freehling, Prelude to Civil War , p. 262

- ↑ Address to the people of the United States , quoted in State papers on nullification , p. 71

- ↑ The change was necessary because the constitution did not allow governors to have two consecutive terms.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 75f.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 78

- ↑ Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , S. 21f.

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 278

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 80

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process p.15

- ↑ Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , p 31ff.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 79f.

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 279

- ↑ Available online at Yale University's Avalon Project , accessed July 2, 2012

- ↑ For the text of the Force Bill, which was finally passed, see Wikisource

- ^ Merrill D. Peterson, The Jefferson Image in the American Mind . Oxford University Press, New York 1960; Reprint with new introduction: University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville and London 1998, p. 59

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 89

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 281

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 89f.

- ↑ Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , p 34

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 162

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 95f.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 97ff.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 159ff.

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 159-162

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 162-165. The two laws were, on the one hand, the concession for the official printing house of the House of Representatives, which did not go to the Jackson-friendly Francis Preston Blair and his Globe , but to the national-republican National Intelligencer . The other law concerned Jackson's requested sale of the federal stake in Second Bank of the United States, which the house refused.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 99

- ^ A b c Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , p. 18

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 99f.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 100

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 165

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 165f.

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 167f.

- ^ Freehling, Prelude to Civil War , p. 291, Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 282f.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 168

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , S. 19f.

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 169ff.

- ^ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism and the Force Bill Debate , p. 253

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 171f.

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 173f.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , p.20

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 174

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 174-176

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 176

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , p.20

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , pp. 285f.

- ^ Arthur M. Schlesinger: The Age of Jackson . Little, Brown and Co., Boston et al. a., 1945, p. 96

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , pp. 284–286

- ^ Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 284; Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, southern discontents, and the American political process , p. 21

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk, pp. 180-182

- Jump up ↑ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism, and the Force Bill Debate , pp. 253–25.

- ^ Arthur M. Schlesinger: The Age of Jackson . Little, Brown and Co., Boston et al. a., 1945, p. 96, Freehling, Road to Disunion , pp. 284-286

- ↑ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism, and the Force Bill Debate, 253

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 180

- ↑ Stampp, The Concept of a Perpetual Union , pp. 28-32

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , p. 185

- ↑ Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , pp. 21ff., P. 34, p. 38; with a similar response Freehling, Road to Disunion , p. 286

- ↑ Latner, The Nullification Crisis and Republican Subversion , p 38

- ↑ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 180-182

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , p.1

- ^ A book title by William Freehling

- ^ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism, and the Force Bill Debate , p. 249

- ^ Charles M. Wiltse: John C. Calhoun, Nullifier 1829–1839 , Bobbs-Merill, Indianapolis 1949, p. 172

- ^ Ellis, Union at Risk , pp. 182f.

- ^ Ericson, The Nullification Crisis, American Republicanism, and the Force Bill Debate , p. 250

- ↑ Ratcliffe, The nullification crisis, discontents southern, and the American political process , p.23

- ^ Sean Wilentz : The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln . Norton, New York 2005, ISBN 0-393-05820-4 , pp. 388f.